Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral

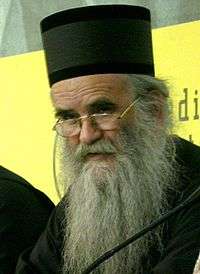

The Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral (Serbian: Митрополија црногорско-приморска) is the largest eparchy (diocese) of the Serbian Orthodox Church in modern Montenegro. Founded in 1219 by Saint Sava, as the Eparchy of Zeta,[1] it continued to exist, without interruption, up to the present time, and remained one of the most prominent dioceses of the Serbian Orthodox Church.[2] The current Metropolitan bishop is Amfilohije Radović (since 1990). His official title is "Archbishop of Cetinje and Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral" (Serbian: Архиепископ цетињски и митрополит црногорско-приморски).[3]

Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral | |

|---|---|

Cetinje Monastery, seat of the Metropolitanate | |

| Location | |

| Territory | Montenegro |

| Headquarters | Cetinje, Montenegro |

| Statistics | |

| Population - Total | 400,000 est. |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Eastern Orthodox |

| Sui iuris church | Serbian Orthodox Church |

| Established | 1219 (as Eparchy of Zeta) |

| Language | Church Slavonic Serbian |

| Current leadership | |

| Bishop | Amfilohije Radović |

| Map | |

-en.svg.png) | |

| Website | |

| https://mitropolija.com/ | |

History

Eparchy of Zeta (1219–1346)

The Eparchy of Zeta was founded in 1219 by Sava of the Nemanjić dynasty, the first Archbishop of the autocephalous Serbian Orthodox Church. After receiving the autocephaly from the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and confirmation from the Byzantine Emperor, Archbishop Sava organized the area under his ecclesiastical jurisdiction into nine bishoprics. One of these was the Bishopric of Zeta (the southern half of modern Montenegro, and northern part of modern Albania). The seat of the bishops of Zeta was the Monastery of Holy Archangel Michael in Prevlaka (near modern Tivat). The first bishop of Zeta was St. Sava's disciple Ilarion (fl. 1219).[4][1][5]

Upon the proclamation of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in 1346, the Bishopric of Zeta was among several eparchies elevated to the honorary rank of metropolitanate, by the decision of the state-church council, held in Skopje, and presided by the Serbian Emperor Stefan Dušan.[6][7]

Metropolitanate of Zeta (1346–1496)

After the dissolution of the Serbian Empire (1371), the region of Zeta was ruled by the House of Balšići, and in 1421 it was integrated into the Serbian Despotate.[8] During that period, the Republic of Venice gradually conquered coastal regions of Zeta, including cities of Kotor, Budva, and the Bar and Ulcinj.[9] Metropolitanate of Zeta was directly affected by the Venetian advance. In 1452, the Venetians destroyed the Cathedral Monastery in Prevlaka, in order to facilitate their plans for the gradual conversion of the Eastern Orthodox Christians from these parts of the coast into the Roman Catholic faith.[10] After that, the seat of the Metropolitanate moved several times, transferring between St Mark's Monastery in Budva, the Monastery of Prečista Krajinska, St Nicholas's Monastery on Vranjina (Skadar Lake), and St Nicholas's Monastery in Obod (Rijeka Crnojevića). Finally, it was moved to Cetinje, in the region of Old Montenegro, where the Cetinje Monastery was built in 1484, by Prince Ivan Crnojević of Zeta.[11]

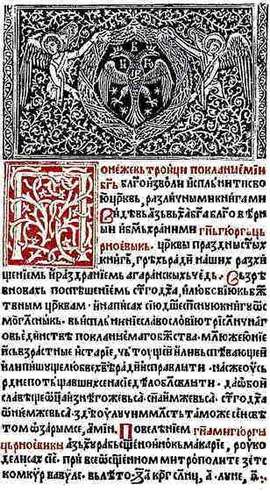

Starting from the end of the 15th century, mountainous regions of Zeta became known as Crna Gora (Serbian: Црна Гора), meaning the Black Mountain, hence the Montenegro.[12] In 1493, Prince Ivan's son and successor, Prince Đurađ Crnojević (1490-1496), opened a printing house in Cetinje, run by Hieromonk Makarije, and produced the first ever book to be printed among the South Slavs.[13] It was the "Cetinje Octoechos", a Serb-Slavonic translation from the original Greek of a service book that is still used to this day in the daily cycle of services in the Orthodox Church. In 1496, entire Zeta, including Montenegro, fell to the Turks, but the Metropolitanate survived.[14]

Eparchy of Cetinje in 16th and 17th century

After 1496, the Eparchy of Cetinje (Serbian: Цетињска епархија), as well as other eparchies of the Serbian Orthodox Church, continued to exist under the new Ottoman rule. It had diocesan jurisdiction over Old Zeta, known now as Old Montenegro, keeping its seat in Cetinje.[15] It had spiritual influence over the territory between Bjelopavlići and Podgorica to the Bojana River. The eparchy also included some parts of Herzegovina, from Grahovo to Čevo. From 1557 to 1766, eparchy was under constant jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć.[16][17]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the bishops and the local Christian leaders led armed resistance against the Ottomans on several occasions, with some degree of success. Though the Ottomans nominally ruled the Sanjak of Montenegro, the Montenegrin mountains were never completely conquered. The bishops and local leaders often allied themselves with the Republic of Venice. At the beginning of the 17th century, Montenegrins fought and won two important battles at Lješkopolje (1603 and 1613), under the leadership and command of metropolitan Rufim Njeguš. This was the first time that the metropolitan had led and defeated the Ottomans.[18]

Metropolitanate of Cetinje under the Petrović-Njegoš

Entire territory of the Metropolitanate was severely affected during the Morean War, and in 1692 the old Cetinje Monastery was devastated. In 1697, new metroplitan Danilo Petrović-Njegoš was elected, as first among several hierarchs from the Petrović-Njegoš family,[19] who would hold the same office in succession up to 1851. Metropolitan Danilo (1697-1735) was greatly respected, not only as a spiritual leader, but also as leader of the people. He combined in his hands both spiritual and secular power, thus establishing a form of "hierocracy". He became the first Prince-Bishop of the Old Montenegro, and continued to oppose the Ottoman Empire, while maintaining traditional ties with the Venetian Republic. He also established direct ties with the Russian Empire, seeking and receiving financial aid and political protection.[20][21]

His successors continued the same policy. Metropolitans Sava II Petrović-Njegoš (1735–1750, 1766-1781) and Vasilije Petrović-Njegoš (1750-1766) had to balance between Ottomans, Venetians, and Russians.[22][23] During that time, metropolitans of Cetinje continued to be ordained by the Serbian Patriarchs of Peć (until 1766),[19] and later by the Serbian Metropolitans of Karlovci in Habsburg Monarchy (until 1830).[24] After brief tenure of Arsenije Plamenac (1781–1784), several new policies were introduced by Metropolitan Petar I Petrović-Njegoš (1784–1830),[25] who initiated the unification process between the Old Montenegro and the region of Brda.[26][27] The same process was completed by his successor Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (1830–1851),[28] who received consecration from the Russian Holy Synod in 1833,[29] establishing a practice that lasted until 1885. As a reformer of state administration, Petar II made preparations for separation of spiritual and secular power,[30] and upon his death such separation was implemented.[31] His successors became: Prince Danilo Petrović-Njegoš as a secular ruler, and metropolitan Nikanor Ivanović as a spiritual leader, new metropolitan of Montenegro.[32][33]

A principal eparchy in Montenegro (1852–1918)

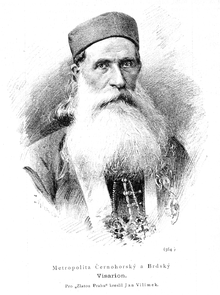

The Eparchy was reorganized during the rule of Prince Danilo I (1852-1860), first secular ruler of the newly proclaimed Principality of Montenegro. Offices of ruling prince and metropolitan were separated,[32] and diocesan administration was modernized. First metropolitan to be elected just as a church leader was Nikanor Ivanović in 1858. He was deposed and exiled in 1860 by new prince Nikola (1860-1918),[34] who established a firm state control over the church administration. During his long reign, metropolitans Ilarion Roganović (since 1863), and Visarion Ljubiša (since 1882) undertook some important reforms of church administration. In 1878, the Principality of Montenegro was recognized as ad independent state, and it was also enlarged, by annexing Old Herzegovina and some other regions.[35][36] Until that time, Eastern Orthodox Christians of the Old Hezegovina belonged to the Metropolitanate of Herzegovina, centered in Mostar, still under the Ottoman rule. Such diocesan affiliation was no longer maintainable, and for the newly annexed regions a new bishopric was created, the Eparchy of Zahumlje and Raška, with seat in Nikšić. Since that time, there were two eparchies in Montenegro: the old Metropolitanate, still centered in Cetinje, and the newly created Eparchy of Zahumlje and Raška, centered in Nikšić. No ecclesiastical province with joint church bodies was created until 1904, under the metropolitan Mitrofan Ban (1884-1920), when a Holy Synod was established,[37][34] formally consisting of two bishops, but because of the long vacancy in Nikšić, it did not start to function until 1908.[38]

During the long reign of Prince and (from 1910) King Nikola I Petrović (1860-1918), who was a Serbian patriot,[39] rising political aspirations of his government included not only the securing of the Serbian throne for his dynasty, but also the renewal of the old Serbian Patriarchate of Peć.[40] On the occasion of the elevation of Montenegro to the rank of Kingdom, in 1910,[41] the prime minister of Montenegro, Lazar Tomanović, staited: The Metropolitanate of Cetinje is the only Saint Sava's episcopal seat which has been preserved without interruption to this day, and as such it represents the lawful throne and a descendant of the Patriarchate of Peć.[42] Such aspirations were strengthened after the liberation of Peć during the successful enlargement of state territory of Montenegro in 1912,[43] when another eparchy was created for several annexed territories that until then belonged to the Eparchy of Raška and Prizren. Its regions annexed to Montenegro were reorganized as the new Eparchy of Peć (1913).[44] From that time, the Holy Synod started to function in full capacity, with three bishops.

Modern history of the Eparchy (1918-2006)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Following the end of the First World War (1914-1918), the Kingdom of Montenegro was united with the Kingdom of Serbia on 26 (13 o.s.) November 1918, by the proclamation of the newly elected Podgorica Assembly,[45] and soon after that, on 1 December of the same year, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was created,[46] known since 1929 as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The political and national unification was carried out under the auspices of the Karađorđević dynasty, and thus a long-standing dynastic rivalry between the two royal families, the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty of Montenegro and the Karađorđević dynasty of Serbia, was finally resolved, without mutual agreement.[47]

Political unification was followed by the unification of all Eastern Orthodox jurisdictions within the borders of the new state. Initial decision to include dioceses in Montenegro into the process of ecclesiastical unification was reached on 29 (16 o.s.) December 1918 by the Holy Synod, consisted of all three hierarchs in Montenegro: Mitrofan Ban of Cetinje, Kirilo Mitrović of Nikšić, and Gavrilo Dožić of Peć. On that day, the Holy Synod met in Cetinje and unanimously accepted the following proposal: "The independent Serbian Orthodox Holy Church in Montenegro shall be united with the autocephalous Orthodox Church in the Kingdom of Serbia".[48] Soon after that, further steps towards ecclesiastical unification were made. From 24 to 28 May 1919, a conference of all Eastern Orthodox bishops within the borders of the unified state was held in Belgrade, and it was presided by metropolitan Mitrofan Ban of Montenegro, who was also elected president of the newly created Central Synod.[49] Under his leadership, the Central Synod prepared the final proclamation of Church unification on 12 September 1920. The creation of the unified Serbian Orthodox Church was also confirmed by King Alexander I.[50]

Old metropolitan Mitrofan Ban was succeeded in the autumn of 1920 by Gavrilo Dožić, who became new Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral.[51] In 1931, under the provisions of the newly adopted Constitution of the Serbian Orthodox Church, the Eparchy of Zahumlje and Raška with its seat in Nikšić was abolished, and its territory was added to the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral. In the same time, the Eparchy of Kotor and Dubrovnik was also abolished, and divided, its Kotor region being added to the Metropolitanate. In 1938, Metropolitan Gavrilo Dožić of Montenegro was elected Serbian Patriarch, and Joanikije Lipovac was elected new Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral, in 1940.[52]

During the Second World War, Yugoslavia was occupied by Axis powers in 1941, and the territory of Montenegro was organized as the Italian governorate of Montenegro (1941-1943), followed by the German occupation of Montenegro (1943-1944). The Metropolitanate was affected severely during the occupation, and more than hundred priests and other clergymen from the territory of Montenegro lost their lives during the war.[53] During that time, Montenegrin fascist Sekula Drljević tried to create an independent Kingdom of Montenegro, as a satellite state of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, but that project failed because of the lack of support among people. His attempt was challenged by the 13 July Uprising in 1941, which had support from the both sides of political spectrum. Metropolitan Joanikije Lipovac cooperated closely with several right-wing movements, and also tried to mediate with local Italian and German officials in occupied Montenegro, thus provoking animosity of the left-wing Yugoslav Partisans. In 1944, when Yugoslav Communists took the power, he had to flee, but was arrested and executed without trial in 1945. In 2001, he was sanctified as a hieromartyr by the Serbian Orthodox church.

Under the Yugoslav Communist rule (1944-1989), the Metropolitanate suffered constant repression at the hands of the new regime. Persecution was particularly severe during the first years of Communist rule (1944-1948) The new regime exerted direct pressure on the clergy in order to crush all forms of anti-communist opposition.[54] In the same tame, many church properties were confiscated, some under the provisions of new laws, while other were taken illegally and forcefully. Several churches and even some minor monasteries were closed, and their buildings turned into police stations and warehouses.[55] In the same time, new Montenegrin nation was proclaimed, as distinctive and separate from Serbian nation.[56] In 1954, Metropolitan Arsenije Bradvarević (1947-1960) was arrested, trialed and sentenced as an enemy of the communist regime. He was imprisoned from 1954 to 1958, and then kept in house arrest until 1960.[57][58] He was succeeded by Metropolitan Danilo Dajković (1961-1990), whose activities were also monitored closely by state authorities.[59][60] In 1970-1972, communist regime destroyed the Lovćen Church, dedicated to Saint Petar of Cetinje, and desecrated the tomb of metropolitan Petar II Petrović-Njegoš, who was buried there, replacing the church with a secular mausoleum.[61][62]

In 1990, Amfilohije Radović was elected new Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral. By that time, the communist regime in Yugoslavia was collapsing, and first democratic elections in Montenegro were held in 1990. In 1992, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was created, consisting of Montenegro and Serbia. Under the Constitution of Montenegro (1992), freedom of religion was restored. Political changes were followed by a period of church revival.[63] The number of priests, monks and nuns, as well as the number of the faithful, increased and many monasteries and parish churches were rebuilt and reopened. For example, from only 10 active monasteries with about 20 monks and nuns in 1991, Montenegro now has 30 active monasteries with more than 160 monks and nuns.[64] The number of parish priests also increased from 20 in 1991 to more than 60 today.[65] In 2001, diocesan administration in the region was reorganized: some northern and western regions were detached from the Metropolitanate, and on that territory new Eparchy of Budimlja and Nikšić was created.[66][67]

Recent history of the Eparchy, since 2006

In the spring of 2006, the independence referendum was held, and Montenegro became a sovereign state. In the same time, the Bishops' Council of the Serbian Orthodox Church decided to form a regional Bishops' Council for Montenegro, consisted of bishops representing dioceses on the territory of Montenegro. By the same decision, Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral was appointed president of the regional Bishops' Council.[68] In the autumn of 2007, due to illness and advanced age of Serbian Patriarch Pavle Stojčević, Metropolitan Amflohije Radović of Montenegro was appointed administrator of the Patriarchal Throne, by the Holy Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Old Patriarch Pavle died in 2009, and Metropolitan Amfilohije continued to administer the Patriarchal Throne until the election of new Serbian Patriarch Irinej Gavrilović in 2010.[69]

Since Montenegro became an sovereign country in 2006, after a narrow independence referendum, relations between state authorities and the Metropolitanate became increasingly complex. As a strong supporter of Serbian-Montenegrin unionism, Metropolitan Amfilohije was seen as an opponent to newly proclaimed Montenegrin independence, and thus a new political dimension to several ecclesiastical disputes was added.[70] One of those disputes was related to claims and activities of a separate Montenegrin Orthodox Church, that was created in 1993 by a group of Montenegrin nationalists, but never recognized as canonical.[71][72] During the following years, various disputes arose, mainly over the question of historical and canonical legitimacy and effective control over some church objects and properties.[73] Recent announcements of state authorities, related to potential confiscation of church properties, have provoked a strong public manifestation of support for the Metropolitanate.[74]

Media publications

"Svetigora" (Serbian: Светигора) is a periodical journal of the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral, published and edited by "Publishing and Information Institution of the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral". Contains mostly the church teachings, poetry, lectures, spiritual lessons, reportages, news and chronicles from the Metropolitanate, the SPC and the all other Orthodox churches.

Monasteries

The Metropolitanate has the following monasteries:[75]

- Banja

- Beška

- Vojnići

- Vranjina

- Gornji Brčeli

- Gradište

- Dajbabe

- Dobrska Ćelija

- Donji Brčeli

- Duga Moračka

- Duljevo

- Žanjica

- Ždrebaonik

- Kom

- Miholjska prevlaka

- Morača

- Moračnik

- Obod

- Orahovo

- Ostrog

- Podlastva

- Podmaine

- Podostrog

- Praskvica

- Prečista Krajinska

- Svetog Preobraženja

- Reževići

- Rustovo

- Savina

- Stanjevići

- Starčeva Gorica

- Ćelija Piperska

- Ćirilovac

- Cetinje

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral. |

- List of Metropolitans of Montenegro

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Montenegro

- Christianity in Montenegro

- Serbs of Montenegro

- Eparchies of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ (Podgorica)

References

- Ćirković 2004, p. 43.

- Aleksov 2014, p. 92-95.

- Official Page of the Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral

- Fine 1994, p. 116-117.

- Curta 2006, p. 392-393.

- Fine 1994, p. 309-310.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 64-65.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 91-92.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 92-93.

- Fine 1994, p. 520.

- Fine 1994, p. 534, 603.

- Fine 1994, p. 532.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 110, 138.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 110.

- Fine 1994, p. 534.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 135.

- Sotirović 2011, p. 143–169.

- Станојевић 1975b, p. 97.

- Aleksov 2014, p. 93.

- Jelavich 1983a, p. 84-85.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 185-186.

- Jelavich 1983a, p. 85-86.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 186.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 177.

- Aleksov 2014, p. 93-94.

- Jelavich 1983a, p. 86-88, 247-249.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 186-187.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 189-190.

- Džankić 2016, p. 116.

- Aleksov 2014, p. 94.

- Jelavich 1983a, p. 249-254.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 215.

- Aleksov 2014, p. 94-95.

- Aleksov 2014, p. 95.

- Jelavich 1983b, p. 35.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 225.

- Глас Црногорца, vol. 33 (1904), no. 1, p. 1.

- Дурковић-Јакшић 1991, p. 64.

- Jelavich 1983b, p. 34.

- Дурковић-Јакшић 1991, p. 72.

- Jelavich 1983b, p. 37.

- Глас Црногорца, vol. 39 (1910), no. 35, p. 2.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 245.

- Дурковић-Јакшић 1991, p. 74.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 251, 258.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 251-252.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 258.

- Decision of the Holy Synod, No. 1169, 16 December 1918, Cetinje.

- Вуковић 1996, p. 321.

- Слијепчевић 1966, p. 611-612.

- Вуковић 1996, p. 107-109.

- Вуковић 1996, p. 236-237.

- Пузовић 2015, p. 211-220.

- Džankić 2016, p. 117.

- Слијепчевић 1986, p. 135.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 275.

- Слијепчевић 1986, p. 215, 224, 259.

- Вуковић 1996, p. 37-38.

- Слијепчевић 1986, p. 259-260.

- Вуковић 1996, p. 161.

- Wachtel 2004, p. 143–144, 147.

- Džankić 2016, p. 117-118.

- Džankić 2016, p. 119.

- Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral: Monasteries

- Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral: Parishes

- Džankić 2016, p. 122.

- Будимљанско-никшићка епархија кроз историју

- Communique of the Diocesan Council of the Orthodox Church in Montenegro (2010)

- Buchenau 2014, p. 79-80.

- Džankić 2016, p. 123-124.

- Buchenau 2014, p. 85.

- Džankić 2016, p. 120-121.

- Statement of The Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Coastlands (2009)

- Mass service held in Montenegro in defense of Serbian Church (2019)

- Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral: Monasteries

Sources

- Aleksov, Bojan (2014). "The Serbian Orthodox Church". Orthodox Christianity and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Southeastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 65–100. ISBN 9780823256068.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buchenau, Klaus (2014). "The Serbian Orthodox Church". Eastern Christianity and Politics in the Twenty-First Century. London-New York: Routledge. pp. 67–93. ISBN 9781317818663.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cattaruzza, Amaël; Michels, Patrick (2005). "Dualité orthodoxe au Monténégro". Balkanologie: Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires. 9 (1–2): 235–253.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815390.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Дурковић-Јакшић, Љубомир (1991). Митрополија црногорска никада није била аутокефална. Београд-Цетиње: Свети архијерејски синод Српске православне цркве, Митрополија црногорско-приморска.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Džankić, Jelena (2016). "Religion and Identity in Montenegro". Monasticism in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Republics. London-New York: Routledge. pp. 110–129. ISBN 9781317391050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2008). "Serbian Orthodox Church". Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 519–520. ISBN 9781438110257.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ивановић, Филип (2006). Проблематика аутокефалије Митрополије црногорско-приморске. Подгорица-Цетиње: Унирекс, Светигора.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Јанковић, Марија (1984). "Саборне цркве Зетске епископије и митрополије у средњем веку (Cathedral Churches of the Bishopric and Metropolitanate of Zeta in Middle Ages)". Историјски часопис. 31: 199–204.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Јанковић, Марија (1985). Епископије и митрополије Српске цркве у средњем веку (Bishoprics and Metropolitanates of Serbian Church in Middle Ages). Београд: Историјски институт САНУ.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983a). History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521274586.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983b). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. 2. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mileusnić, Slobodan, ed. (1989). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. 7. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morrison, Kenneth (2009). Montenegro: A Modern History. London-New York: I.B.Tauris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morrison, Kenneth; Čagorović, Nebojša (2014). "The Political Dynamics of Intra-Orthodox Conflict in Montenegro". Politicization of Religion, the Power of State, Nation, and Faith: The Case of Former Yugoslavia and its Successor States. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 151–170. doi:10.1057/9781137477866_7. ISBN 978-1-349-50339-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pavlovich, Paul (1989). The History of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Serbian Heritage Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Popović, Svetlana (2002). "The Serbian Episcopal sees in the thirteenth century". Старинар (51: 2001): 171–184.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Пузовић, Предраг (2015). "Страдање свештеника током Првог светског рата на подручију Цетињске, Пећске и Никшићке епархије" (PDF). Богословље: Часопис Православног богословског факултета у Београду. 74 (2): 211–220.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radić, Radmila (2007). "Serbian Christianity". The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 231–248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Слијепчевић, Ђоко М. (1962). Историја Српске православне цркве. 1. Минхен: Искра.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Слијепчевић, Ђоко М. (1966). Историја Српске православне цркве. 2. Минхен: Искра.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Слијепчевић, Ђоко М. (1986). Историја Српске православне цркве. 3. Келн: Искра.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sotirović, Vladislav B. (2011). "The Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in the Ottoman Empire: The First Phase (1557–94)". 25 (2): 143–169. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Станојевић, Глигор (1975a). "Црна Гора у XVI вијеку". Историја Црне Горе. 3. Титоград: Редакција за историју Црне Горе. pp. 1–88.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Станојевић, Глигор (1975b). "Црна Гора у XVII вијеку". Историја Црне Горе. 3. Титоград: Редакција за историју Црне Горе. pp. 89–227.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Станојевић, Глигор (1975c). "Црна Гора у XVIII вијеку". Историја Црне Горе. 3. Титоград: Редакција за историју Црне Горе. pp. 229–499.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Вуковић, Сава (1996). Српски јерарси од деветог до двадесетог века (Serbian Hierarchs from the 9th to the 20th Century). Евро, Унирекс, Каленић.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wachtel, Andrew B. (2004). "How to Use a Classic: Petar Petrović-Njegoš in the Twentieth Century". Ideologies and National Identities: The Case of Twentieth-Century Southeastern Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 131–153. ISBN 9789639241824.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Official Pages of the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral

- Venice Commission (2015): Draft Joint Interim Opinion on the Draft Law on Freedom of Religion of Montenegro

- Venice Commission (2019): Montenegro: Opinion on the Draft Law on Freedom of Religion or Beliefs and Legal Status of Religious Communities

- Council of Europe (2019): Montenegro: Provisions on religious property rights include positive changes to out-dated legislation, but need more clarity, says Venice Commission

- Freedom of Religion or Belief in Montenegro: Conclusions (2019)