Sandžak

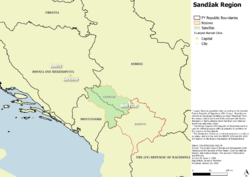

Sandžak (/ˈsændʒæk/; Serbian Cyrillic: Санџак, pronounced [sǎndʒak]; Albanian: Sanxhak) or Sanjak, is a historical[1][2][3] geo-political region in Serbia and Montenegro.[4] The name Sandžak derives from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, a former Ottoman administrative district. Serbs refer to the northern part of the region by its medieval name Raška.

Sandžak

| |

|---|---|

Geographical region1 | |

Map of Sandžak region | |

| Countries | Serbia and Montenegro |

| Largest city | Novi Pazar |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8,686 km2 (3,354 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2011) | 390,737 |

| • Density | 45.33/km2 (117.4/sq mi) |

| ^ "Sandžak" is not an official subdivision of either Serbia or Montenegro. | |

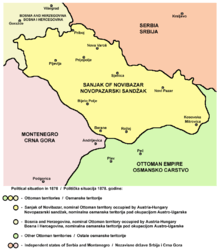

Between 1878 and 1909 the region was placed under Austro-Hungarian occupation, following which it was ceded back to the Ottoman Empire. In 1912 the region was divided between the kingdoms of Montenegro and Serbia. The most populous city in the region is Novi Pazar in Serbia.

Etymology

Sandžak is the transcription of Turkish sancak (sanjak, "province");[5] the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, known in Serbo-Croatian as Novopazarski sandžak. In Serbian, the region is known by its pre-Ottoman name, Raška.

Geography

Sandžak stretches from the southeastern border of Bosnia and Herzegovina[6] to the borders with Kosovo[7][8][9] and Albania[9] at an area of around 8,500 square kilometers. Six municipalities of Sandžak are in Serbia (Novi Pazar, Sjenica, Tutin, Prijepolje, Nova Varoš, and Priboj[10]), and five in Montenegro (Pljevlja, Bijelo Polje, Berane, Rožaje, and Plav[11]). Sometimes the Montenegrin municipality of Andrijevica is also regarded as part of Sandžak.

The most populated municipality in the region is Novi Pazar (100,410),[12] while other large municipalities are: Pljevlja (31,060),[13] and Priboj (27,133).[12] In Serbia, the municipalities of Novi Pazar and Tutin are part of the Raška District,[14] while the municipalities of Sjenica, Prijepolje, Nova Varoš, and Priboj, are part of the Zlatibor District.[14]

History

The Serbian Despotate was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1455. During the Ottoman rule, many inhabitants converted to Islam. The conversions were caused by number of factors, mainly economic as Muslims paid lower taxes.[15] The Muslims were also privileged compared to Christians, who were unable to work in the administration or testify in court against Muslims.[16] The second factor that contributed to the Islamisation were migrations. A large demographic shift occurred as Serbs fought several wars against the Ottoman Empire. The Turks drove the Christian population northwards, while Muslims were driven to the Ottoman territory. The land abandoned by the Serbs was settled by Muslims, mainly ethnic Serbs who confessed Islam and Turks, but also significant population from the Caucasus, the Middle East and the Asia Minor. Large migrations occurred throughout the 18th and 19th century. The third factor of Islamisation was the geographical location of Sandžak, which allowed it to become a trade centre, facilitating conversions amongst merchants.[17]

The second half of the 19th century was very important in terms of shaping the current ethnic and political situation in Sandžak. Austria-Hungary supported Sandžak's separation from the Ottoman Empire, or at least its autonomy within it. The reason was to prevent Serbia and Montenegro from unifying, and allow Austria-Hungary's further expansion to the Balkans. Per these plans, Sandžak was seen as part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while its Muslim population played a significant role giving Austrian-Hungarians a pretext of protecting the Muslim minority from the Christian Orthodox Serbs.[18]

Administratively, it was part of the Sanjak of Bosnia until 1790, when it become a separated Sanjak of Novi Pazar. However, in 1867, it become a part of the Bosnia Vilayet that consisted of seven sanjaks, including the Sanjak of Novi Pazar. This led to Sandžak Muslims identifying themselves with other Slavic Muslims in Bosnia.[19]

In October 1912, Sandžak was captured by Serbian and Montenegrin troops in the First Balkan War, and its territory was divided between Serbia and Montenegro.[20] Many Slavic Muslims and Albanian inhabitants of Sandžak emigrated to Turkey as muhajirs. There are numerous colonies of Sandžak Bosniaks in Turkey, in and around Edirne, Istanbul, Adapazarı, Bursa, and Samsun, among other places. During World War I, Sandžak was occupied by Austria-Hungary between 1915 and 1918, as it had been previously between 1878 and 1908. Following World War I, it was included in the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. It was a link between the Muslims in the West in Bosnia and Herzegovina and those in the East in Kosovo and Macedonia. Sandžak was the only region in Serbia populated by the Slavic Muslims.[18] The Sandžak Muslims suffered from the loss of their economic status since the decline of the Ottoman Empire, and during the agrarian reform carried out in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. This led to the Muslim emigrations to the Ottoman Empire.[21]

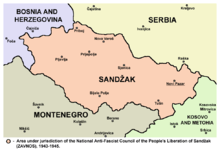

The new communist regime in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia found Sandžak with the Slavic Muslim minority of 43% and the Serb majority of 56%, along with smaller Albanian and Catholic minorities. During the World War II, until its abolition, Sandžak had an equal status to other federal units.[22] The Muslims, who had generally anti-Partisan attitude, wanted unification of Sandžak with Bosnia and Herzegovina, or at least to be taken as a whole either by Serbia or Montenegro. However, Sandžak was later divided between Serbia and Montenegro, the outcome the Muslims wanted the least.[23]

The Anti-Fascist Council of People's Liberation of Sandžak (AVNOS) had been founded on 20 November 1943 in Pljevlja.[24] In January 1944, the Land Assembly of Montenegro and the Bay of Kotor cited Sandžak as part of a future Montenegrin federal unit. However, in March, the Communist Party opposed this, insisting that Sandžak's representatives at AVNOJ should decide on the matter.[25] In February 1945, the Presidency of the AVNOJ made a decision to oppose the Sandžak's autonomy. The AVNOJ explained that the Sandžak hadn't a national basis for an autonomy and opposed crumbling of the Serbian and Montenegrin totality.[26] On 29 March 1945 in Novi Pazar, the AVNOS accepted the decision of the AVNOJ and divided itself between Serbia and Montenegro.[27] Sandžak was divided based on the 1912 demarcation line.[26]

Economically, Sandžak remained undeveloped. It had a small amount of crude and low-revenue industry. Freight was transported by trucks over poor roads. Schools for business students, which remained poor in general education, were opened for working-class youth. The Sandžak had no faculty, not even a department or any school of higher education.[21]

Sandžak saw a process of industrialisation, during which factories were opened in several cities, including Novi Pazar, Prijepolje, Priboj, Ivangrad, while the coal mines were opened in the Prijepolje area. The urbanisation caused a major social and economic shift. Many people left villages for towns. The national composition of the urban centres was changed to the disadvantage of the Muslims, as most of those who inhabited the cities were Serbs. The Muslims continued to lose their economic status, continuing the trend inherited from the time of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the agrarian reform in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[21] The emigration of the Muslims to Turkey also continued, caused by the general underdevelopment of the region, disagreement with the communist authorities and the mistrust with the Serbs and Montenegrins, but also due to the nationalisation and expropriation of property. Serbs from Sandžak also moved to the wealthier regions of the central Serbia or to Belgrade or Vojvodina, while the Muslims moved to Bosnia and Herzegovina as well.[28]

With the democratic changes in Serbia in 2000, the ethnic Bosniaks were enabled to start participating in the political life in Serbia and Montenegro, including Rasim Ljajić, an ethnic Bosniak, who was a minister in the Government of Serbia and Montenegro, and Rifat Rastoder, who is the Deputy President of the Parliament of Montenegro. Census data shows a general emigration of all nationalities from this underdeveloped region.

Demographics

Sandžak is a very ethnically diverse region. Most Bosniaks declared themselves Muslims by nationality in 1991 census. By the 2002-2003 census, however, most of them declared themselves Bosniaks. There is still a significant minority that identify as Muslims by nationality. There are still some Albanian villages (Boroštica, Doliće and Ugao) in the Pešter region.[29] Factors such as some intermarriage undertaken by two generations with the surrounding Bosniak population along with the difficult circumstances of the Yugoslav wars (1990s) made local Albanians opt to refer to themselves in censuses as Bosniaks.[29]

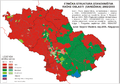

Ethnic map of Sandžak (including Plav and Andrijevica) according to the 2002 census in Serbia and 2003 census in Montenegro. Note: map shows the ethnic majority populations within the municipalities

Ethnic map of Sandžak (including Plav and Andrijevica) according to the 2002 census in Serbia and 2003 census in Montenegro. Note: map shows the ethnic majority populations within the municipalities Ethnic map of Sandžak (excluding Plav and Andrijevica) according to the 2002 census in Serbia and 2003 census in Montenegro. Note: map shows the ethnic majority populations within the settlements

Ethnic map of Sandžak (excluding Plav and Andrijevica) according to the 2002 census in Serbia and 2003 census in Montenegro. Note: map shows the ethnic majority populations within the settlements

Serbian Sandžak

According to the 2011 census in Serbia,[12] a total of 201,728 people live in the Serbian portion of Sandžak. Bosniaks, numbering 142,373 hold an overall majority (59.4%) in this part of region, mainly concentrated in the eastern part of Serbian Sandžak. Serbs, numbering 77,555 (i.e. 32.5%), make up the majority in most of the western part of Serbian Sandžak.

| Municipality | Ethnicity | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bosniaks |

% |

Serbs |

% |

Montenegrins |

% |

Muslims |

% |

Albanians |

% |

others |

% | ||

| Novi Pazar | 77,443 | 77.13 | 16,234 | 16.17 | 44 | 0.04 | 4,102 | 4.08 | 202 | 0.20 | 2,385 | 2.38 | 100,410 |

| Prijepolje | 12,792 | 34.52 | 19,496 | 52.61 | 16 | 0.04 | 3,543 | 9.56 | 18 | 0.05 | 1,194 | 3.22 | 37,059 |

| Tutin | 28,041 | 90.00 | 1,090 | 3.50 | 16 | 0.05 | 1,092 | 3.51 | 29 | 0.09 | 887 | 2.85 | 31,155 |

| Priboj | 3,811 | 14.05 | 20,582 | 75.86 | 119 | 0.44 | 1,944 | 7.16 | 3 | 0.01 | 674 | 2.48 | 27,133 |

| Sjenica | 19,498 | 73.88 | 5,264 | 19.94 | 15 | 0.06 | 1,234 | 4.68 | 29 | 0.11 | 352 | 1.33 | 26,392 |

| Nova Varoš | 788 | 4.73 | 14,899 | 89.55 | 31 | 0.19 | 526 | 3.16 | 3 | 0.02 | 391 | 2.35 | 16,638 |

| Serbian Sandžak | 142,373 | 59.62 | 77,555 | 32.48 | 241 | 0.10 | 12,441 | 5.21 | 284 | 0.12 | 5,893 | 2.47 | 238,787 |

Montenegrin Sandžak

According to the 2011 census in Montenegro, the Montenegrin part numbers 151,950 people. The ethnic composition of the Montenegrin part is significantly more mixed than that of the Serbian part. No ethnic groups forms an absolute majority in the Montenegrin part.

| Municipality | Ethnicity | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bosniaks |

% |

Serbs |

% |

Montenegrins |

% |

Muslims |

% |

Albanians |

% |

others |

% | ||

| Bijelo Polje | 12,592 | 27.34 | 16,562 | 35.96 | 8,808 | 19.13 | 5,985 | 13.00 | 57 | 0.12 | 2,047 | 4.45 | 46,051 |

| Berane | 6,021 | 17.72 | 14,592 | 42.95 | 8,838 | 26.02 | 1,957 | 5.76 | 70 | 0.21 | 2,492 | 7.34 | 33,970 |

| Pljevlja | 2,128 | 6.91 | 17,569 | 57.07 | 7,494 | 24.34 | 1,739 | 5.65 | 17 | 0.06 | 1,839 | 5.97 | 30,786 |

| Rožaje | 19,269 | 83.91 | 822 | 3.58 | 401 | 1.75 | 1,044 | 4.55 | 1,158 | 5.04 | 270 | 1.17 | 22,964 |

| Plav | 6,803 | 51.90 | 2,098 | 16.00 | 822 | 6.27 | 727 | 5.55 | 2,475 | 18.88 | 183 | 1.40 | 13,108 |

| Andrijevica | 0 | 0.00 | 3,137 | 61.86 | 1,646 | 32.46 | 7 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.02 | 280 | 5.52 | 5,071 |

| Montenegrin Sandžak | 46,813 | 30.81 | 54,780 | 36.05 | 28,009 | 18.43 | 11,459 | 7.54 | 3,778 | 2.49 | 7,111 | 4.68 | 151,950 |

Sandžak as a whole

A calculation of the two censuses puts Sandžak's total population at just over 390,000. The relative majority is held by the roughly 189,190 Bosniaks, who form 48.4% of the region's population. Serbs form 33.9% (132,345), while Montenegrins form 7.25% (28,323), Muslims by nationality 6.11% (23,900), and Albanians 1.04% (4,062).

| Municipality | Ethnicity | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bosniaks |

% |

Serbs |

% |

Montenegrins |

% |

Muslims |

% |

Albanians |

% |

others |

% | ||

| Novi Pazar | 77,443 | 77.13 | 16,234 | 16.17 | 44 | 0.04 | 4,102 | 4.08 | 202 | 0.20 | 2,385 | 2.38 | 100,410 |

| Bijelo Polje | 12,592 | 27.34 | 16,562 | 35.96 | 8,808 | 19.13 | 5,985 | 13.00 | 57 | 0.12 | 2,047 | 4.45 | 46,051 |

| Prijepolje | 12,792 | 34.52 | 19,496 | 52.61 | 16 | 0.04 | 3,543 | 9.56 | 18 | 0.05 | 1,194 | 3.22 | 37,059 |

| Berane | 6,021 | 17.72 | 14,592 | 42.95 | 8,838 | 26.02 | 1,957 | 5.76 | 70 | 0.21 | 2,492 | 7.34 | 33,970 |

| Tutin | 28,041 | 90.00 | 1,090 | 3.50 | 16 | 0.05 | 1,092 | 3.51 | 29 | 0.09 | 887 | 2.85 | 31,155 |

| Pljevlja | 2,128 | 6.91 | 17,569 | 57.07 | 7,494 | 24.34 | 1,739 | 5.65 | 17 | 0.06 | 1,839 | 5.97 | 30,786 |

| Priboj | 3,811 | 14.05 | 20,582 | 75.86 | 119 | 0.44 | 1,944 | 7.16 | 3 | 0.01 | 674 | 2.48 | 27,133 |

| Sjenica | 19,498 | 73.88 | 5,264 | 19.94 | 15 | 0.06 | 1,234 | 4.68 | 29 | 0.11 | 352 | 1.33 | 26,392 |

| Rožaje | 19,269 | 83.91 | 822 | 3.58 | 401 | 1.75 | 1,044 | 4.55 | 1,158 | 5.04 | 270 | 1.17 | 22,964 |

| Nova Varoš | 788 | 4.73 | 14,899 | 89.55 | 31 | 0.19 | 526 | 3.16 | 3 | 0.02 | 391 | 2.35 | 16,638 |

| Plav | 6,803 | 51.90 | 2,098 | 16.00 | 822 | 6.27 | 727 | 5.55 | 2,475 | 18.88 | 183 | 1.40 | 13,108 |

| Andrijevica | 0 | 0.00 | 3,137 | 61.86 | 1,646 | 32.46 | 7 | 0.14 | 1 | 0.02 | 280 | 5.52 | 5,071 |

| Sandžak | 189,186 | 48.42 | 132,335 | 33.86 | 28,250 | 7.23 | 23,900 | 6.12 | 4,062 | 1.04 | 13,004 | 3.33 | 390,737 |

Gallery

A wall built during the Ottoman period in Novi Pazar

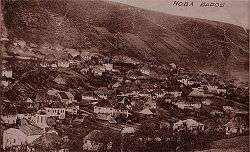

A wall built during the Ottoman period in Novi Pazar Nova Varoš in 1930's

Nova Varoš in 1930's Kučanska Mosque, Rožaje from 1830.

Kučanska Mosque, Rožaje from 1830.- Nova Varoš Centre in 2004

- Husein-pasha's mosque, Pljevlja

%2C_Novi_Pazar%2C_Srbija.jpg) Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, Ras near Novi Pazar, 8-9th century

Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, Ras near Novi Pazar, 8-9th century Stari Ras fortress near Novi Pazar, 8th century

Stari Ras fortress near Novi Pazar, 8th century Đurđevi Stupovi monastery, near Novi Pazar, 12th century

Đurđevi Stupovi monastery, near Novi Pazar, 12th century White Angel, fresco from Mileševa monastery near Prijepolje, c. 1235

White Angel, fresco from Mileševa monastery near Prijepolje, c. 1235 Sopoćani monastery, 13th century

Sopoćani monastery, 13th century

See also

References

Notes

- Stjepanović, Dejan (2012). "Regions and Territorial Autonomy in Southeastern Europe". In Gagnon, Alain-G.; Keating, Michael (eds.). Political autonomy and divided societies: Imagining democratic alternatives in complex settings. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 194. ISBN 9780230364257.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roth, Clémentine (2018). Why Narratives of History Matter: Serbian and Croatian Political Discourses on European Integration. Nomos Verlag. p. 268. ISBN 9783845291000.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duda, Jacek (2011). "Islamic community in Serbia - the Sandžak case". In Górak-Sosnowska, Katarzyna (ed.). Muslims in Poland and Eastern Europe: Widening the European Discourse on Islam. University of Warsaw: Faculty of Oriental Studies. p. 327. ISBN 9788390322957.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karen Dawisha; Bruce Parrott (13 June 1997). Politics, Power and the Struggle for Democracy in South-East Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-0-521-59733-3.

- "Dictionary.com - Sanjak entry".

- "Position of the Municipality of Priboj".

- "Geographic position of Municipality of Tutin".

- "Geographic position of Municipality of Rožaje".

- "Profile of Municipality of Plav" (PDF).

- "Territorial organisation of Republic of Serbia".

- "Territorial organization of Montenegro" (PDF).

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF).

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro" (PDF).

- "Government of Republic of Serbia - Administrative Okrugs (Regions)".

- Górak-Sosnowska 2011, p. 328.

- Todorović 2012, p. 13.

- Górak-Sosnowska 2011, p. 328–329.

- Górak-Sosnowska 2011, p. 329.

- Todorović 2012, p. 11.

- "The Austrian Occupation of Novibazar, 1878–1909". Mount HolyOak. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- Hadžišehović, Butler & Risaluddin 2003, p. 132.

- Banac 1988, p. 100.

- Banac 1988, p. 100–101.

- Jelić & Strugar 1985, p. 82, 134.

- Banac 1988, p. 101.

- Banac 1988, p. 102.

- Jelić & Strugar 1985, p. 144.

- Hadžišehović, Butler & Risaluddin 2003, p. 133.

- Andrea Pieroni, Maria Elena Giusti, & Cassandra L. Quave (2011). "Cross-cultural ethnobiology in the Western Balkans: medical ethnobotany and ethnozoology among Albanians and Serbs in the Pešter Plateau, Sandžak, South-Western Serbia." Human Ecology. 39. (3): 335. "The current population of the Albanian villages is partly "bosniakicised", since in the last two generations a number of Albanian males began to intermarry with (Muslim) Bosniak women of Pešter. This is one of the reasons why locals in Ugao were declared to be "Bosniaks" in the last census of 2002, or, in Boroštica, to be simply "Muslims", and in both cases abandoning the previous ethnic label of "Albanians", which these villages used in the census conducted during "Yugoslavian" times. A number of our informants confirmed that the self-attribution "Albanian" was purposely abandoned in order to avoid problems following the Yugoslav Wars and associated violent incursions of Serbian para-military forces in the area. The oldest generation of the villagers however are still fluent in a dialect of Ghegh Albanian, which appears to have been neglected by European linguists thus far. Additionally, the presence of an Albanian minority in this area has never been brought to the attention of international stakeholders by either the former Yugoslav or the current Serbian authorities."

Sources

- Banac, Ivo (1988). With Stalin Against Tito: Cominformist Splits in Yugoslav Communism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801421861.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Górak-Sosnowska, Katarzyna (2011). Muslims in Poland and Eastern Europe: Widening the European Discourse on Islam. Warszaw: Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Warszaw. ISBN 8390322951.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hadžišehović, Munevera; Butler, Thomas J.; Risaluddin, Saba (2003). A Muslim Woman in Tito's Yugoslavia. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1585443042.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jelić, Ivan; Strugar, Novak (1985). War and revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945. Belgrade: Socialist Thought and Practice.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sandžak. |