Miami International Airport

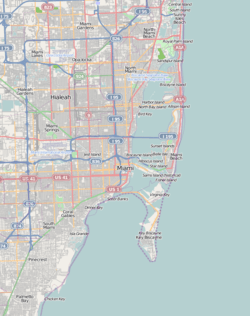

Miami International Airport (IATA: MIA, ICAO: KMIA, FAA LID: MIA), also known as MIA and historically as Wilcox Field, is the primary airport serving the Miami area, Florida, United States, with over 1,000 daily flights to 167 domestic and international destinations, and one of three airports serving this area. The airport is in an unincorporated area in Miami-Dade County, 8 miles (13 km) northwest of Downtown Miami, in metropolitan Miami,[4] adjacent to the cities of Miami and Miami Springs, and the village of Virginia Gardens. Nearby are the cities of Hialeah and Doral, and the Census-designated place of Fontainebleau.

Miami International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

_(8204606870).jpg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Miami-Dade County | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Miami-Dade Aviation Department (MDAD) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Greater Miami | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Unincorporated Miami-Dade County | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1928 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Focus city for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 9 ft / 3 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 25°47′36″N 080°17′26″W | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | iflymia.com | ||||||||||||||||||||||

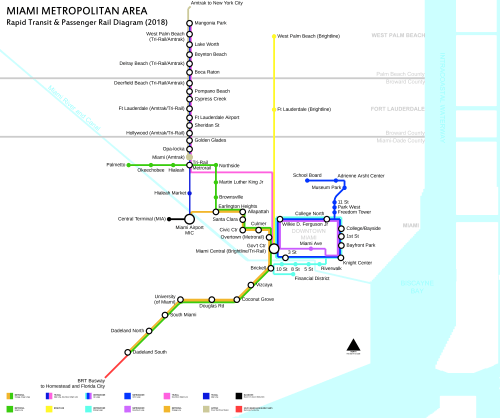

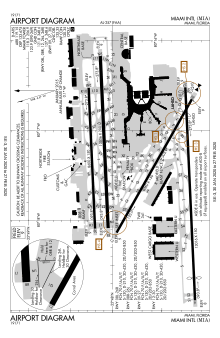

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||||||

MIA Location within Miami  MIA MIA (Florida)  MIA MIA (the United States)  MIA MIA (North America) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2019) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

It is South Florida's main airport for long-haul international flights and a hub for the Southeastern United States, with passenger and cargo flights to cities throughout the Americas, Europe, Africa, and Western Asia, as well as cargo flights to East Asia. It is the largest gateway between the United States and south to Latin America, and is one of the largest airline hubs in the United States, owing to its proximity to tourist attractions, local economic growth, large local Latin American and European populations, and strategic location to handle connecting traffic between North America, Latin America, and Europe.

In 2018, 45,044,312 passengers traveled through the airport, making it the 13th busiest airport in the United States and 40th busiest in the world by total passenger traffic. In 2019, MIA served 45,924,466 passengers, a passenger record for the airport. It is the 3rd busiest airport in the United States by international passenger traffic. MIA is Florida's busiest airport by total aircraft operations and total cargo traffic and its second busiest by total passenger traffic after Orlando International Airport.[5]

The airport is American Airlines' third largest hub and serves as its primary gateway to Latin America. Miami also serves as a focus city for Avianca, Frontier Airlines, and LATAM, both for passengers and cargo operations. In the past, it has been a hub for Braniff International Airways, Eastern Air Lines, Air Florida, the original National Airlines, the original Pan American World Airways ("Pan Am"), United Airlines, Iberia Airlines and Fine Air.

History

- For the World War II and United States Air Force Reserve use of the airport, see Miami Army Airfield

The first airport on the site of MIA opened in the 1920s and was known as Miami City Airport. Pan American World Airways opened an expanded facility adjacent to City Airport, Pan American Field, in 1928. Pan American Field was built on 116 acres of land on 36th Street and was the only mainland airport in the eastern United States that had port of entry facilities. Its runways were located around the threshold of today's Runway 26R. Eastern Airlines began to serve Pan American Field in 1931, followed by National Airlines in 1936. National used a terminal on the opposite side of LeJeune Road from the airport, and would stop traffic on the road in order to taxi aircraft to and from its terminal. Miami Army Airfield opened in 1943 during the Second World War to the south of Pan American Field: the runways of the two were originally separated by railroad tracks, but the two airfields were listed in some directories as a single facility.[6] Following World War II in 1945, the City of Miami established a Port Authority and raised bond revenue to purchase Pan American Field, which had been since renamed 36th Street Airport, from Pan Am. It merged with the former Miami Army Airfield, which was purchased from the United States Army Air Force south of the railroad in 1949 and expanded further in 1951 when the railroad line itself was moved south to make more room. The old terminal on 36th Street was closed in 1959 when the center modern passenger terminal (since greatly expanded) opened. United States Air Force Reserve troop carrier and rescue squadrons also operated from the airport from 1949 through 1959, when the last unit relocated to nearby Homestead Air Force Base, (now Homestead Air Reserve Base).

Nonstop flights to Chicago and Newark Liberty International Airport in northeast New Jersey started in late 1946, but nonstops didn't reach west beyond St. Louis and New Orleans until January 1962. Nonstop transatlantic flights to Europe began in 1970. In the late 1970s and early 1980s Air Florida had a hub at MIA, with a nonstop flight to London, England which it acquired from National upon the latter's merger with Pan Am. Air Florida ceased operations in 1982 after the crash of Air Florida Flight 90.[7] British Airways flew a Concorde SST (supersonic transport) triserial between Miami and London via Washington, D.C. (Dulles International Airport) from 1984 to 1991.[8]

After former Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman became president of Eastern Airlines in 1975, he moved Eastern's headquarters from Rockefeller Center in New York City to Building 16 in the northeast corner of MIA, Eastern's maintenance base. Eastern remained one of the largest employers in the Miami metropolitan area until ongoing labor union unrest, coupled with the airline's acquisition by union antagonist Frank Lorenzo in 1986, ultimately forced the airline into bankruptcy in 1989.[7]

In the midst of Eastern's turmoil American Airlines CEO Bob Crandall sought a new hub in order to utilize new aircraft which AA had on order. AA studies indicated that Delta Air Lines would provide strong competition on most routes from Eastern's hub at Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in Atlanta, but that MIA had many key routes only served by Eastern. American announced that it would establish a base at MIA in August 1988. Lorenzo considered selling Eastern's profitable Latin American routes to AA as part of a Chapter 11 reorganization of Eastern in early 1989, but backed out in a last-ditch effort to rebuild the MIA hub. The effort quickly proved futile, and American purchased the routes (including the route authority between Miami and London then held by Eastern sister company Continental Airlines) in a liquidation of Eastern which was completed in 1990.[7] Later in the 1990s, American transferred more employees and equipment to MIA from its failed domestic hubs at Nashville, Tennessee and Raleigh–Durham, North Carolina. The hub grew from 34 daily departures in 1989 to 157 in 1990, 190 in 1992 and a peak of 301 in 1995, including long-haul flights to Europe and South America.[9] Today Miami is American's largest air freight hub and is the main connecting point in the airline's north–south international route network.

Pan American World Airways ("Pan Am"), the other longtime key carrier at MIA, was acquired by Delta Air Lines in 1991, but filed for bankruptcy shortly thereafter. Its remaining international routes from Miami to Europe and Latin America were sold to United Airlines for $135 million as part of Pan Am's emergency liquidation that December.[7] United's Latin American hub offered 24 daily departures in the summer of 1992, growing to 36 daily departures to 21 destinations in the summer of 1994, but returned to 24 daily departures in the summer of 1995 and never expanded further.[10] United ended flights from Miami to South America, and shut down its Miami crew base, in May 2004, reallocating most Miami resources to its main hub in O'Hare International Airport in Chicago.[11] United ceased all mainline service to Miami in 2005 with the introduction of its low-cost product Ted.[10]

Iberia also established a Miami hub in 1992, positioning a fleet of DC-9 aircraft at MIA to serve destinations in Central America and the Caribbean. The hub took advantage of rights granted under the 1991 bilateral aviation agreement between the United States and Spain.[12] However, the September 11, 2001 attacks made it necessary for many aliens to obtain a visa in order to transit the United States, and as a result United Airlines and Iberia closed their hubs in 2004.[13] Miami remains the most important hub between Europe and Latin America, and today more European carriers serve MIA than any other airport in the United States, except John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York.

Future

MIA is projected to process 77 million passengers and 4 million tons of freight annually by 2040.[14] To meet such a demand, the Miami-Dade Board of County Commissioners approved a $5 billion improvement plan to take place over 15 years and concluding in 2035.

The comprehensive plan includes concourse optimization, construction of two on-site luxury hotels, and expansion of the airport's cargo capacity.[15]

Operations

Miami International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the year ending December 31, 2018 the airport had 416,032 aircraft operations, average 1,139 per day: 86% scheduled commercial, 10% air taxi, 4% general aviation and <1% military.[4] The budget for operations was $600 million in 2009.[16]

Facilities and aircraft

Miami International Airport covers 1,335 hectares (3,300 acres) and has four runways:[4]

- 8L/26R: 8,600 ft × 150 ft (2,621 m × 46 m)

- 8R/26L: 10,506 ft × 200 ft (3,202 m × 61 m)

- 9/27: 13,016 ft × 150 ft (3,967 m × 46 m)

- 12/30: 9,360 ft × 150 ft (2,853 m × 46 m)

28 aircraft are based at this airport: 46% multi-engine and 54% jet.[4]

MIA has a number of air cargo facilities. The largest cargo complex is located on the west side of the airport, inside the triangle formed by Runways 12/30 and 9/27. Cargo carriers such as LAN Cargo, Atlas Air, Southern Air, Amerijet International and DHL operate from this area. The largest privately owned facility is the Centurion Cargo complex in the northeast corner of the airport, with over 51,000 m2 (550,000 sq ft) of warehouse space.[17] FedEx and UPS operate their own facilities in the northwest corner of the airport, off of 36th Street. In addition to its large passenger terminal in Concourse D, American Airlines operates a maintenance base to the east of Concourse D, centered around a semicircular hangar originally used by National Airlines which can accommodate three widebody aircraft.[18]

Fire protection at the airport is provided by Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Department[19] Station 12.[20]

Terminals and concourses

The airport has 131 gates in total. The main terminal at MIA dates back to 1959, with several new additions. Semicircular in shape, the terminal has one linear concourse (Concourse D) and five pier-shaped concourses, lettered counter-clockwise from E to J (Concourse A is now part of Concourse D; Concourses B and C were demolished so that Concourse D gates could be added in their place; naming of Concourse I was skipped to avoid confusion with the number 1.). From the terminal's opening until the mid-1970s the concourses were numbered clockwise from 1 to 6.

Level 1 of the terminal contains baggage carousels and ground transportation access. Level 2 contains ticketing/check-in, shopping and dining, and access to the concourses. The airport currently has three immigration and customs facilities (FIS), located in Concourse D, Level 3, Concourse E, Level 3, and in Concourse J, Level 3. The Concourse D FIS and Concourse E FIS can be utilized by flights arriving at all gates in Concourse D, all gates in Concourse E, and most gates in Concourse F. The Concourse J FIS can be utilized by flights arriving at some gates in Concourse H and all gates in Concourse J. However, all gates in Concourse G and some gates in Concourses F and H do not have the facilities to route passengers to any FIS, and therefore can only be used for domestic arrivals. MIA is unique among American airports in that all of its facilities are common-use, meaning that they are assigned by the airport and no one airline holds ownership or leases on any terminal space or gates, thus giving the airport much more flexibility in terminal and gate assignments and allowing it to make full use of existing facilities. The entire airport became common-use by the 1990s. The single terminal facility is divided into three sections known as the North Terminal, Central Terminal, and South Terminal.

The free MIA Mover connects the airport with the Miami Intermodal Center, where the car rental facility and bus terminal has relocated. The MIC also houses the airport Metrorail station and Tri-Rail terminal.

The airport has four parking facilities: a two-level short-term parking lot directly in front of Concourse E, two seven-story parking garages (Dolphin and Flamingo) located within the terminal's curvature and connected to the terminal via overhead walkways on Level 3, and a surface parking lot (South Parking Lot) east of the Flamingo Garage.[21] The parking areas were originally numbered, with the short-term lot known as Park 1, and the parking garages were originally four separate structures numbered Park 2–5. In the 1990s, the parking garages were combined, with Park 3 and 5 becoming the Dolphin Garage, which was simultaneously expanded to accommodate the new Concourse A, and Park 2 and 4 became the Flamingo Garage. The two parking garages are connected via a bridge at the top level.

North Terminal (Blue)

The North Terminal was previously the site of Concourses A, B, C, and D, each a separate pier. Concourse D was one of the airport's original 1959 concourses, having opened as Concourse 5. After modifications similar to that of former Concourse C during the mid-1960s, it was extended in 1984, and the original portion was completely rebuilt from 1986 to 1989[22] and connected to the immigration and customs hall in Concourse E, allowing it to handle international arrivals. The Concourse D FIS now provides immigration and customs services for international flights arriving at this terminal.[23] Along with former Concourses B and C, the concourse once housed the Eastern Air Lines base of operations. Another Texas Air Corporation affiliate joined the eastern side during the 1980s; Continental Airlines used gates on the west side of the concourse during the 1980s.

The North Terminal construction merged the four piers into a single linear concourse designated Concourse D. This configuration was adopted in order to increase the number of aircraft that can simultaneously arrive and depart from the terminal, allowing each gate to handle approximately twice as many operations per day.[24] The construction process started with the extension of the original A and D concourses in the late 1990s. By the mid-2000s, the gates on the east side of Concourse D were closed in order to make room for new gates being constructed as part of the North Terminal Development project. In 2004, a new extension to the west was opened, consisting of Gates D39 through D51. Concourse B was demolished in 2005; in summer 2009, Gates D21 to D25 opened where Concourse B once stood. Concourse C was demolished in 2009; in August 2013, Gates D26, D27, and D28 opened where Concourse C once stood and were the final North Terminal gates to open.[25] Concourse A closed in November 2007 and re-opened in July 2010 as a 14-gate eastern extension of Concourse D. In August 2010, a further extension for American Eagle flights was opened, designated as Gate D60.[26]

The Skytrain automated people mover, built by Parsons and Odebrecht with trains from Sumitomo Corporation and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, opened in September 2010.[26] It transports domestic passengers between four stations within Concourse D, located at gates D17, D24, D29 and D46; it also connects arriving international passengers who have not yet cleared border customs to the Concourse D FIS.[27]

The North Terminal construction began in 1998 and was slated for completion in 2005, but was delayed several times due to cost overruns. The project was managed by American Airlines until the Miami-Dade County Aviation Department took over in 2005.[28] The initial project inception was designed by Corgan Associates, Anthony C Baker Architects and Planners, Perez & Perez, and Leo A Daly.[29] After revisions to the design, the project was accomplished by the architectural firm of Harper Partners, who was instrumental in completion and finalization of the design for the two major projects which were the primary elements of the American Airlines World Gateway Terminal.

Harper Partners served as lead architects for both the Concourse D Shell (450,000 sf of new construction) and for the Harper Partners/Perez & Perez Joint Venture which served as architects for the 1.3 million sf of interior build-out and finishes of the American Airlines World Gateway Terminal. Although certain portions of the project experienced cost overruns, in contrast, both of the Harper Partners projects were completed within less than one and a half percent in total change orders. Harper Partners was recognized by Miami Dade Aviation Department in working aggressively and creatively in recapturing the program's overall construction schedule.[30]

A new international arrivals facility opened in August 2012, and the project reached substantial completion in January 2013. All of the twelve international gates which were designed by the Harper Partners Team of architects were the first to be fully operational and generating revenue for the Miami Dade Aviation Department.[31] The Baggage Handling System's international-to-domestic transfer, which was the last component of the project, was completed in February 2014.[32]

Concourse D

Concourse D is the only concourse located within the North Terminal, and is a 3.6-million-square-foot (330,000 m2) linear concourse 1.2 miles (1.9 km) long with a capacity of 30 million passengers annually. Concourse D has one bus station and 51 gates: D1–D12, D14–D17, D19–D34, D36–D51, D53, D55, D60.[33] American operates two Admirals Clubs within the concourse; one located near Gate D30, and another near Gate D15. American Eagle uses Gates D53, D55, and D60.[34]

Central Terminal (Yellow)

The Central Terminal consists of three concourses, labeled E, F, and G, with a combined total of 52 gates.[33] The Miami-Dade Aviation Department began a three-year, $657 million renovation of the terminal in November 2015, to include a new train in Concourse E and new gates and ticket counters. The airport authority plans to demolish and replace the terminal in stages, while funding upgrades to keep the facilities usable in the interim.

Concourse E

Concourse E has two bus stations and 18 gates: E2, E4–E11, E20–E25, E30-E31, and E33.[33]

Concourse E dates back to the terminal's 1959 opening, and was originally known as Concourse 4. From the start, it was the airport's only international concourse, containing its own immigration and customs facilities. In the mid-1960s, it underwent renovations similar to the airport's other original concourses, but didn't receive its first major addition until the International Satellite Terminal was opened in 1976. Featuring Gates E20–E35 (commonly known as "High E"), the satellite added 12 international gates capable of handling the largest jet aircraft as well as an international intransit lounge for arriving international passengers connecting to other international flights. At the same time, Concourse E's immigration and customs facilities were radically overhauled and expanded. During the late-1980s, the original portion of Concourse E ("Low E") was rebuilt to match the satellite.

The concourse and its satellite were briefly linked by buses then the airport's first automated people mover (Adtranz C-100) opened in 1980, which was replaced in 2016 by a cable propelled MIA e Train — a MiniMetro people mover by Leitner-Poma of America.[35]

Since then, Gate E3 was closed in the 1990s to accommodate a connector between Concourses D and E. In the mid-2000s, the Low E and High E security checkpoints were expanded and merged into one, linking both portions of the concourse without requiring passengers to reclear security. At the same time Gates E32, E34, and E35 were closed to make way for a second parallel taxiway between the Concourse D extension and Concourse E. Concourse E also contains the Central Terminal's immigration and customs halls. The airport authority plans to maintain the "high E" area until 2034, and the "low E" area until 2035.[36]

Concourse E serves Oneworld member airlines British Airways, Finnair, Iberia, and Qatar, along with some American Airlines and American Eagle flights. The concourse contains a premium lounge for international passengers flying in first and business class as well as OneWorld Emerald and Sapphire elite members. On October 25, 2015, British Airways became the third carrier at MIA to operate the Airbus A380, after Lufthansa and Air France. The seasonal A380 service to London–Heathrow uses gate E24, which was specially modified to accommodate the aircraft.

The seven-story Miami–International Airport hotel and many Miami-Dade Aviation Department executive offices are in the Concourse E portion of the terminal. Level 1 houses two domestic baggage carousels. Level 2 is used for check-in by several European, Central American, and Caribbean carriers. Concourse E, along with Concourse F, was once the base of operations for Pan Am and many of MIA's international carriers.

Concourse F

Concourse F has one bus station and 19 gates: F3–F12, F14–F20, F23.[33]

Concourse F dates back to 1959 and was originally known as Concourse 3. Like Concourses D and E, it received renovations in the mid-1960s and was largely rebuilt from 1986 to 1988.[37][38] The gates at the far end of the pier were demolished and replaced by new widebody Gates F10-F23, all of which were capable of processing international arrivals. The departure lounges for Gates F3, F5, F7, and F9 were also rebuilt, and these also became international gates. Currently, the concourse retains a distinctly 1980s feel, and is part of the Central Terminal area. The airport authority plans to maintain the concourse until 2036.[36]

The south side of the concourse was used by Northeast Airlines until its 2010 merger with Delta Air Lines. Likewise, National Airlines flew out of the north side of Concourse F until its 1980 merger with Pan Am, which continued to use the concourse until its 1991 shutdown. When United Airlines acquired Pan Am's Latin American operations, the airline carried on operating a focus city out of Concourse F until completely dismantling it by 2004. From 1993 to 2004, Concourse F was also used by Iberia Airlines for its Miami focus city operation, which linked Central American capitals to Madrid using MIA as the connecting point. As of 2019, Concourse F primarily handles international carriers including Aeroflot, Aer Lingus, Air Europa, Cayman Airways, Eurowings, Surinam Airways, TAP Air Portugal, TUIFly, Volaris, and WestJet as well as international charter flights.

Level 1 of the Concourse F portion of the terminal is used for domestic baggage claim and cruise line counters. Level 2 contains check-in facilities for foreign airlines. Concourse F is unusual in that it is the only concourse with the TSA security checkpoint located on Level 3. Passengers must ascend to the checkpoint, pass through security and then descend back down to Level 2 to board their flights.

Concourse G

Concourse G has one bus station and 15 gates: G2–G12, G14–G16, and G19.[33]

Concourse G is the only one of the original 1959 concourses that has largely remained in its original state, save for the modifications the rest of the airport received in the mid-1960s and an extension in the early 1970s. It is the only concourse at the airport incapable of handling international arrivals. The airport authority plans to maintain the concourse.[39]

South Terminal (Red)

The South Terminal consists of two concourses, H and J, with a combined total of 28 gates.[33]

The South Terminal building and Concourse J opened on August 29, 2007. The new addition is seven stories tall and has 15 international-capable gates, and a total floor area of 1.3 million square feet (120,000 m2), including two airline lounges and several offices. Concourse H primarily serves Delta and its partners in the SkyTeam alliance (such as Aeromexico, Air France and KLM), while Concourse J serves several Star Alliance carriers (including Air Canada, Avianca and Lufthansa) as well as and Delta affiliates, Virgin Atlantic and LATAM Airlines.[40] Prior to 2004, when United Airlines eliminated its Latin America hub at MIA, the South Terminal was intended to house United and its partners in the Star Alliance; the airport spent $1 billion on construction before United withdrew its hub.[41][42]

Concourse H

Concourse H has 13 gates: H3–H12, H14-H15, and H17.[33]

Concourse H was the 20th Street Terminal's first extension, originally built in 1961 as Concourse 1 for Delta Air Lines, which remains in the concourse to this day. This concourse featured a third floor, the sole purpose of which was to expedite access to the "headhouse" gates at the far end. In the late 1970s, a commuter satellite terminal was built just to the east of the concourse. Known as "Gate H2", it featured seven parking spaces (numbered H2a through H2g) designed to handle smaller commuter aircraft. The concourse was dramatically renovated from 1994 to 1998, to match the style of the then-new Concourse A. Moving walkways were added to the third floor, the H1 Bus Station and Gates H3–H11 were completely rebuilt, and the H2 commuter satellite had jetways installed. However, the H1 Bus Station was never used and has since been permanently closed. Due to financial difficulties, headhouse gates H12–H20 were left in their original state.

With the construction of the Concourse J extension in the 2000s, the H2 commuter satellite was demolished. In 2007, with the opening of the South Terminal's immigration and customs facilities, the third floor of Concourse H was closed off and converted into a "sterile circulation" area for arriving international passengers. Gates H4, H6, H8, and H10 were made capable of handling international arrivals, and they currently serve Aeromexico, Air France, Alitalia, KLM and Swiss. Simultaneously, headhouse gates H16, H17, H18, and H20 were closed to allow for the construction of a second parallel taxiway leading to the new Concourse J.

Concourse H historically served as the base of operations for Piedmont's Miami focus city and US Airways Express's commuter operations. Concourse H continues to serve original tenant Delta Air Lines, which uses all of the gates on the west side of the pier and 1 gate on the east side to accommodate international arrivals from Havana.

Concourse J

Concourse J has one bus station and 15 gates: J2–J5, J7–J12, J14–J18.[33]

Concourse J is the newest concourse, having opened on August 29, 2007. Part of the airport's South Terminal project,[43] the concourse was designed by Carlos Zapata and M.G.E., one of the largest Hispanic-owned architecture firms in Florida. The concourse features 15 international-capable gates as well as the airport's only gate (J17) with 3 jet bridges, specifically designed for the Airbus A380. The concourse added a third international arrivals hall to the airport, supplementing the existing ones at Concourses B (since replaced by the facility at Concourse D) and Concourse E while significantly relieving overcrowding at these two facilities.

Former concourses

Concourse A

At the time of its closure, Concourse A had one bus station and 16 gates: A3, A5, A7, A10, A12, A14, A16–A26.

Concourse A was a recent addition to the airport, opening in two phases between 1995 and 1998. The concourse is now part of the North Terminal. Between 1995 and 2007, the concourse housed many of American Airlines' domestic and international flights, as well as those of many European and Latin American carriers.

On November 9, 2007, Concourse A was closed as part of the North Terminal Development Project. It had been closed in order to speed up completion of the North Terminal project, as well as facilitate the addition of the Automated People Mover (APM) system that now spans the length of the North Terminal. The infrastructure of Concourse A reopened on July 20, 2010 as an extension of Concourse D.

Concourse B

At its peak, Concourse B had one bus station and 12 gates: B1, B2–B12, B15.

Concourse B was built in 1975 for Eastern Air Lines as part of the airport's ambitious "Program 70's" initiative. During the 1980s, the existing concourse was rebuilt and expanded, and a new immigration and customs hall was built in the Concourse B section of the terminal, allowing the concourse to process international arrivals. Along with Concourse C and most of Concourse D, it served as Eastern Air Lines' historical base of operations.

After Eastern's shutdown in 1991 it was used by a variety of European and Latin American airlines; by the 2000s (decade), American Airlines was its sole tenant. The concourse was closed in 2004 and torn down the following year as part of the North Terminal Development project. The immigration and customs hall remained open until 2007, when it was closed along with Concourse A.

Concourse C

At the time of its closure, Concourse C had 3 gates: C5, C7, C9.

Concourse C opened as Concourse 6 in 1959, serving Eastern Air Lines. During the mid-1960s, Concourse C received an extension of its second floor and was equipped with air conditioning. Since then, it did not receive any major interior modifications or renovations. Following the renumbering of gates and concourses in the 1970s, Concourse C had Gates C1 to C10. The opening of an international arrivals hall in Concourse B during the 1980s saw Gate C1 receive the ability to process international arrivals.

Following the demise of Eastern Air Lines in 1991 the concourse was used by a variety of Latin American carriers. Many of these airlines' flights would arrive at Concourse B and then be towed to Concourse C for departure. By the end of the decade, the construction of American's baggage sorting facility between Concourses C and D saw the closure of all gates on the west side of the concourse, with Gate C1 following soon afterward. From the 2000s (decade) on, the concourse consisted of just four domestic-only gates, each of which were capable of accommodating small-to-medium jet aircraft from the Boeing 737 up to the Airbus A300, and American was the sole tenant.

As part of the North Terminal Development project, Concourse C closed on September 1, 2009, and was demolished. The demolition of Concourse C allowed for the construction of new gates where the concourse stood.

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

Notes

- ^a Flights from Miami to Brasilia have a stopover in Punta Cana for refuelling due to the Boeing 737 MAX groundings. However, GOL does not carry local traffic between Miami and Punta Cana. This flight is flown with a Boeing 737-800, which cannot fly from Brasilia to Miami directly due to Brasilia's high altitude.

- ^b TUI fly Netherlands flights incoming from Amsterdam fly via Orlando-Sanford to Miami. However, the return flight from Miami is nonstop.

Cargo

The airport is one of the largest in terms of cargo in the United States, and is the primary connecting point for cargo between Latin America and the world.[92] In 2018, Miami International Airport served 2.3 million tons of freight. Ninety-six different carriers are involved in shifting over two million tons of freight annually and ensuring the safe travel of over 40 million passengers, according to the Miami International Airport corporate brochure.[93] It was first in International freight and third in total freight for 2008. In 2000, LAN Cargo opened up a major operations base at the airport and currently operates a large cargo facility at the airport. Most major passenger airlines, such as American Airlines use the airport to carry hold cargo on passenger flights, though most cargo is transported by all-cargo airlines. UPS Airlines and FedEx Express both base their major Latin American operations at MIA.

Additional cargo carriers serving Miami[97]

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atlanta, Georgia | 799,000 | American, Delta, Frontier |

| 2 | New York–LaGuardia, New York | 698,000 | American, Delta, Frontier |

| 3 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 592,000 | American |

| 4 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 570,000 | American, Frontier, United |

| 5 | New York–JFK, New York | 497,000 | American, Delta |

| 6 | Los Angeles, California | 441,000 | American |

| 7 | Newark, New Jersey | 437,000 | American, Frontier, United |

| 8 | Washington–National, D.C. | 408,000 | American |

| 9 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 370,000 | American, Frontier |

| 10 | Charlotte, North Carolina | 361,000 | American |

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | São Paulo–Guarulhos, Brazil | 830,132 | American, LATAM |

| 2 | London–Heathrow, United Kingdom | 776,480 | American, British Airways, Virgin Atlantic |

| 3 | Buenos Aires–Ezeiza, Argentina | 735,222 | Aerolíneas Argentinas, American, LATAM |

| 4 | Havana, Cuba | 673,701 | American, Delta |

| 5 | Panama City, Panama | 631,233 | American, Copa Airlines |

| 6 | Bogotá, Colombia | 574,859 | American, Avianca, LATAM |

| 7 | Lima, Peru | 574,473 | American, Avianca, LATAM |

| 8 | Madrid, Spain | 574,140 | Air Europa, American, Iberia |

| 9 | Mexico City, Mexico | 516,803 | Aeroméxico, American, Interjet, Volaris |

| 10 | Santo Domingo-Las Américas, Dominican Republic | 437,769 | American |

Airline market share

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Percent of market share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | American Airlines | 14,753,000 | 67.55% |

| 2 | Delta Air Lines | 2,581,000 | 11.82% |

| 3 | United Airlines | 1,308,000 | 5.99% |

| 4 | Envoy Air | 965,000 | 4.42% |

| 5 | Frontier Airlines | 669,000 | 3.06% |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 45,924,466 | 2009 | 33,886,025 |

| 2018 | 45,044,312 | 2008 | 34,063,531 |

| 2017 | 44,071,313 | 2007 | 33,740,416 |

| 2016 | 44,584,603 | 2006 | 32,533,974 |

| 2015 | 44,350,247 | 2005 | 31,008,453 |

| 2014 | 40,941,879 | 2004 | 30,165,197 |

| 2013 | 40,562,948 | 2003 | 29,595,618 |

| 2012 | 39,467,444 | 2002 | 30,060,241 |

| 2011 | 38,314,389 | 2001 | 31,668,450 |

| 2010 | 35,698,025 | 2000 | 33,621,273 |

Ground transportation

Miami International Airport has direct public transit service to Miami-Dade Transit's Metrorail, Metrobus network; Greyhound Bus Lines and to the Tri-Rail commuter rail system.

Miami International Airport uses the MIA Mover, a free people mover system to transfer passengers between MIA terminals and Miami Airport station that opened to the public on September 9, 2011. By 2015, the Station also provided direct service to Tri-Rail and Amtrak services.

On July 28, 2012, the Miami Airport station and the Metrorail Orange Line opened the over two mile segment between Earlington Heights and the MIC, providing rapid passenger rail service from Miami International Airport to downtown and points south.

To/from Metrorail, Downtown and South Beach

Metrorail operates the Orange Line train from Miami International Airport to destinations such as Downtown, Brickell, Civic Center, Coconut Grove, Coral Gables, Dadeland, Hialeah, South Miami and Wynwood. It takes approximately 15 minutes to get from the airport to Downtown.

Miami-Dade Transit operates an Airport Flyer bus which connects MIA directly to South Beach.[100]

To/from Tri-Rail/Amtrak, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach

MIA is served directly by Tri-Rail, Miami's commuter rail system, which began service on April 5, 2015. Tri-Rail connects MIA to northern Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties. Tri-Rail directly serves points north such as: Boca Raton, Deerfield Beach, Delray Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Hollywood, Pompano Beach and West Palm Beach.[101]

In the future, Amtrak will also serve Miami Airport station with the Silver Star and the Silver Meteor trains. These provide daily rail services to Orlando, Jacksonville, Washington, DC, Philadelphia and New York City. Service was originally expected to begin in late 2016, but due to the fact that the platforms are at insufficient length for the winter season since the trains exceed 13 cars (despite the platforms being sufficient during all other seasons as the trains normally consist of up to 9 cars), the date of service has been moved indefinitely.[102]

Taxis and shuttles

Taxis and shuttles provide flat rates to destinations within Miami.

Rental cars

MIA has a newly completed rental car center at the new Miami Central Station.[103]

Accidents and incidents

- On January 22, 1952, an Aerodex Lockheed Model 18 Lodestar on a test flight crashed after takeoff due to engine failure, all 5 occupants were killed.[104]

- On August 4, 1952, a Curtiss C-46 Commando on a ferry flight crashed on approach to MIA because of the failure of the elevator control system, all 4 occupants died.[105]

- On March 25, 1958, Braniff International Airways Flight 971, a Douglas DC-7 crashed 5 km WNW of MIA after attempting to return to the airport because of an engine fire crashing into an open marsh, 9 passengers out of 24 on board were killed.[106]

- On October 2, 1959, a Vickers Viscount of Cubana de Aviación was hijacked on a flight from Havana to Antonio Maceo Airport, Santiago by three men demanding to be taken to the United States. The aircraft landed at Miami International Airport.[107]

- On February 12, 1963, Northwest Airlines Flight 705, a Boeing 720, crashed into the Everglades while en route from Miami to Portland, Oregon via Chicago O'Hare, Spokane, and Seattle. All 43 passengers and crew perished.

- On February 13, 1965, an Aerolíneas de El Salvador (AESA) Curtiss C-46 Commando, a cargo flight, had an engine failure shortly after takeoff and crashed into an automobile junkyard, both occupants perished.[108]

- On March 5, 1965, a Fruehaf Inc. Lockheed Model 18 Lodestar nosed down after takeoff due to elevator trim tab problems, both occupants were killed.[109]

- On June 23, 1969, a Dominicana de Aviación Aviation Traders Carvair, a modified DC-4, en route to Santo Domingo was circling back to Miami International Airport with an engine fire when it crashed into buildings 1 mile short of Runway 27. All 4 crewmembers aboard the Carvair and 6 on the ground were killed.[110]

- On April 14, 1970, an Ecuatoriana de Aviacion Douglas DC-7, a cargo flight, crashed after takeoff from MIA beyond the runway and slid 890 feet before striking a concrete abutment, both occupants were killed.[111]

- On December 29, 1972, Eastern Air Lines Flight 401, a Lockheed L-1011, crashed into the Everglades. The plane had left JFK International Airport in New York City bound for Miami. (the subject of Hollywood movie, The Ghost of Flight 401). There were 101 fatalities out of the 176 passengers and crew on board.[112]

- On June 21, 1973, a Warnaco Inc. Douglas DC-7, a cargo flight, crashed into the Everglades 6 minutes after takeoff in heavy rain, wind and lightning. All 3 occupants perished.[113]

- On December 15, 1973, a Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation operated by Aircraft Pool Leasing Corp, a cargo flight, crashed 1.3 miles E of MIA because of overrotation of the aircraft causing a stall, crashing into a parking lot and several homes, all 3 occupants were killed along with 6 on the ground.[114]

- On September 27, 1975, a Canadair CL-44 operated by Aerotransportes Entre Rios (AER), crashed after takeoff because of an external makeshift flight control lock on the right elevator, 4 crew and 2 passengers of the 10 on board died.[115]

- On January 15, 1977, a Douglas DC-3, registration N73KW of Air Sunshine crashed shortly after take-off on a domestic scheduled passenger flight to Key West International Airport, Florida. All 33 people on board survived.[116]

- On January 6, 1990, a Grecoair Lockheed JetStar crashed after aborting takeoff and exiting the runway, 1 occupant of the 2 on board died.[117]

- On May 11, 1996, ValuJet Flight 592, a McDonnell Douglas DC-9 crashed into the Everglades 10 minutes after taking off from MIA while en route to Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport after a fire broke out in the cargo hold, killing 110 people.

- On August 7, 1997, Fine Air Flight 101 , a Douglas DC-8 cargo plane, crashed onto NW 72nd Avenue less than a mile (1.6 km) from the airport. All 4 occupants on board and 1 person on the ground were killed.

- On September 15, 2015, Qatar Airways Flight 778 to Doha overran Runway 9 during takeoff and collided with the approach lights for Runway 27. The collision, which went unnoticed during the 13.5-hour flight, tore a 18-inch (46 cm) hole in the pressure vessel of the Boeing 777-300 aircraft just behind the rear cargo door. The crew was confused by a printout from an onboard computer and erroneously begun takeoff on Runway 9 at the intersection of Taxiway T1 rather than at the end of the runway, which trimmed roughly 1,370 m (4,490 ft) from the available length runway for takeoff.[118][119]

References

- FAA Airport Master Record for MIA (Form 5010 PDF)

- Miami International Airport (March 2019). "Airport Statistics". Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- FAA Airport Master Record for MIA (Form 5010 PDF), effective October 25, 2007

- "Miami Dominates US to Latin America and Caribbean". anna.aero Airline News & Analysis. April 27, 2010. Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- Freeman, Paul. "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Florida: Central Miami Area". Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- Petzinger, Thomas (1996). Hard Landing: The Epic Contest For Power and Profits That Plunged the Airlines into Chaos. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-77449-1.

- Stieghorst, Tom (January 12, 1991). "Concorde Flights Cut To Miami". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- "AAMIAhub". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "UAMIAhub". www.departedflights.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "United Plans Flight, Staff Cuts in Miami". South Florida Business Journal. January 23, 2004. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "TRAVEL ADVISORY; Iberia Plans 9 New Routes At Miami Hub". The New York Times. March 22, 1992. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- "Iberia To Shut Americas Hub At Mia". tribunedigital-sunsentinel. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Miami International Airport Gets $5 Billion Expansion Boost". June 5, 2019.

- Vasquez, Michael (January 19, 2010). "Slot Machines at Miami Airport Aren't Dead Yet". The Miami Herald. Miami, Florida. pp. 37–39. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- "Centurion Cargo". Archived from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- "American's Miami Hub". American Airlines. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- "Airport Fire Rescue Division". Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Department. Miami-Dade County. Archived from the original on March 8, 2005. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- "Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Stations". Miami-Dade Fire Rescue Department. Miami-Dade County. Archived from the original on June 20, 2006. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- "Where to Park". Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- Long, Kim (1989). The American Forecaster Almanac [Airport Changes] (Sixth ed.). Philadelphia: Running Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-89471-627-1.

- "North Terminal International Arrivals Facility". Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- McCormick, Carroll (January–February 2011). "The New MIA: Countdown to Completion" (PDF). Airports International. 44 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "North Terminal Development Miami International Airport". Anthony C. Baker, Architects & Planners, P.C. Archived from the original on August 25, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "Miami International Airport North Terminal". Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- "Miami International Airport Skytrain". Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- Richard, Militza (February 1, 2010). "MIA: An Entirely New Facility" (PDF). Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "Miami International Airport North Terminal Renovation, United States of America". Airport Technology. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- Arteaga, Juan Carlos AIA, NCARB, NTD Program Director, Miami Dade County Aviation Department (2008). "Letter of Commendation", Ref. NTD-GEN-00418, Miami, 24 September 2008. http://mydo.cx/NzhiNTA0

- Arteaga, Juan Carlos AIA, NCARB, NTD Program Director, Miami Dade County Aviation Department (2008). "Letter of Commendation", Ref. NTD-GEN-00418, Miami, 24 September 2008.

- "North Terminal Development (NTD) Program Fact Sheet" (PDF). Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- "Airport Terminal Gates". Miami-Dade Aviation Department. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "American Eagle Celebrates New Location in Miami Hub, Offering Increased Service and Convenience" (PDF) (Press release). Miami-Dade Aviation Department. August 19, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "New MiniMetro train in Miami". Internationale Seilbahn-Rundschau. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- "MIA's Dilapidated Central Terminal Won't Be Fully Demolished Until 2036". The Next Miami. March 30, 2016. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- "Project List Page". MFA Architects. Archived from the original on December 28, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- Achenbach, Joel (December 14, 1986). "The Kingdom and the Power". The Miami Herald. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- "MIA Spending $651 Million To Refurbish Central Terminal, Which Will Be Demolished A Few Years Later". The Next Miami. Archived from the original on December 21, 2015. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- "Airline Directory". Miami International Airport. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- Turnbell, Michael; Hemlock, Doreen (January 27, 2004). "BIG CHANGES AT MIAMI AIRPORT". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 15, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- Haggman, Matthew (August 8, 2010). "MIA expansion comes with hefty price tag". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on February 15, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- Greene, Ronnie; Barry, Rob (September 7, 2007). "Costs, Changes Stalled Terminal at MIA". The Miami Herald. p. A1. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "TImetables". Aer Lingus. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Online timetable". Aeroflot. Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "TImetables". Aeroméxico. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Flight Schedules". Air Canada. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Air Europa Map". Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Air France flight schedule". Air France. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULE AND OPERATIONS". Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Flight schedules and notifications". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Aruba Airlines Destinations". Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Check itineraries". Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Bahamasair". Archived from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Flight Status". Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "British Airways - Timetables". Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Caribbean Airlines Route Map". Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Miami route". Corsair. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- Liu, Jim. "Eastern Airlines June 2020 network additions". Routesonline. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- "Flight Schedule". El Al. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on November 24, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- https://www.wkbw.com/news/local-news/frontier-to-resume-buffalo-to-miami-non-stop-flights-increases-service-to-orlando

- https://news.flyfrontier.com/frontier-airlines-announces-new-nonstop-flights-from-providence-and-boosts-existing-service/

- "Frontier". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Route map". Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Flight times - Iberia". Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Interjet launches routes Monterrey-Los Angeles and Cancún-Miami" (in Spanish). Reportur. November 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- "Flight Schedule". Interjet. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "View the Timetable". KLM. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Flight Status - LATAM Airlines". Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Timetables". LOT Polish Airlines. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Timetable - Lufthansa Canada". Lufthansa. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Route Map | Norwegian". Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Flight timetable". Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Timetable - SAS". Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Route Map & Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Our Routes" (PDF). Sunwing Airlines.

- "Overview Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "All Destinations". TAP Portugal. Archived from the original on May 12, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "TUI Schedule". Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- "Online Flight Schedule". Turkish Airlines. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- "Interactive flight map". Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Volaris Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Flight schedules". Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Cargo Traffic 2010 Final". Airports Council International. August 1, 2011. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "Gateway to the Americas" (PDF). Miami–Dade Aviation Department. June 27, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- https://m.benzinga.com/article/15306881

- https://www.aircargonews.net/airlines/lufthansa-cargo-re-launches-mia-freighter-service/

- http://199.119.0.52/webfids/webfids_cargo

- Miami-Dade County Online Services. "Miami International Airport :: Cargo Airlines :: Miami-Dade County". Miami International Airport. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- "Miami, FL: Miami International (MIA)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Miami, FL: Miami International (MIA)". www.transtats.bts.gov. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Archived from the original on July 19, 2010. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "Airport Flyer". Miami-Dade Transit. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- "Tri-Rail Tickets & Fares". Archived from the original on April 15, 2018. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- Entin, Brian; Francois, Tania (November 5, 2018). "Off the Rails: Amtrak station built near MIA with taxpayer dollars goes unused". WSVN. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- Miami-Dade County Online Services. "Miami International Airport :: MIA Rental Car Center (RCC) :: Miami-Dade County". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Accident description for N3927C at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for N79096 at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for N5904 at the Aviation Safety Network

- "Hijacking description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- Accident description for YS-012C at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for N300N at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for HI-168 at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for HC-AON at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for N627WS at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for N296 at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for N6917C at the Aviation Safety Network

- Accident description for LV-JSY at the Aviation Safety Network

- "N73KW Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- Accident description for N96GS at the Aviation Safety Network

- Hradecky, Simon (September 17, 2015). "Accident: Qatar B773 at Miami on Sep 15th 2015, overran runway on takeoff run and struck approach lights on departure". Aviation Herald. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- Preliminary Report 001/2015 (PDF) (Report). Qatar Civil Aviation Authority. December 7, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Miami International Airport. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Miami International Airport. |

- Official website

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective August 13, 2020

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KMIA

- ASN accident history for MIA

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KMIA

- FAA current MIA delay information

- Miami International Airport - Flight Information

- Miami airport travel data at Airportsdata.net