McDonnell Douglas DC-9

The McDonnell Douglas DC-9 (initially the Douglas DC-9) is a single-aisle airliner designed by the Douglas Aircraft Company. After introducing its heavy DC-8 in 1959, Douglas approved the smaller, all-new DC-9 for shorter flights on April 8, 1963. The DC-9-10 first flew on February 25, 1965 and gained its type certificate on November 23, to enter service with Delta Air Lines on December 8. With five seats across in economy, it had two rear-mounted Pratt & Whitney JT8D turbofans under a T-tail for a cleaner wing, a two-person flight deck and built-in airstairs.

| DC-9 | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| A Northwest Airlines DC-9-31 | |

| Role | Narrow-body jet airliner |

| Manufacturer | Douglas Aircraft Company McDonnell Douglas |

| First flight | February 25, 1965 |

| Introduction | December 8, 1965, with Delta Air Lines |

| Status | In limited service |

| Primary users | USA Jet Airlines Aeronaves TSM Northwest Airlines (historical) Delta Air Lines (historical) |

| Produced | 1965–1982 |

| Number built | 976 |

| Unit cost |

US$5.2M (DC-9-40, 1972)[1] |

| Variants | McDonnell Douglas C-9 |

| Developed into | McDonnell Douglas MD-80 McDonnell Douglas MD-90 Boeing 717 |

The Series 10 are 104 ft (32 m) long for typically 90 coach seats. The Series 30, stretched by 15 ft (4.5 m) to seat 115 in economy, has a larger wing and more powerful engines for a higher maximum takeoff weight (MTOW); it first flew in August 1966 and entered service in February 1967. The Series 20 has the Series 10 fuselage, more powerful engines and the -30 improved wings; it first flew in September 1968 and entered service in January 1969. The Series 40 was further lengthened by 6 ft (2 m) for 125 passengers, and the final DC-9-50 series first flew in 1974, stretched again by 8 ft (2.5 m) for 135 passengers. When deliveries ended in October 1982, 976 had been built. Smaller variants competed with the BAC One-Eleven, Fokker F28 and Sud Aviation Caravelle, and larger ones with the original Boeing 737.

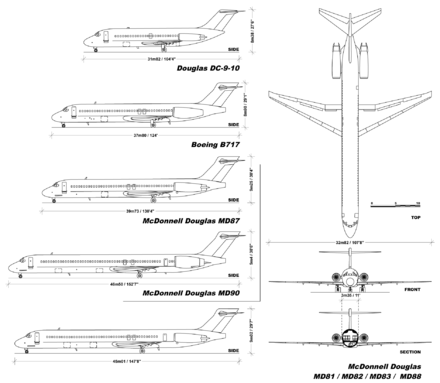

The DC-9 was followed by the MD-80 series in 1980, a lengthened DC-9-50 with a larger wing and a higher MTOW. Itself developed into the MD-90 in the early 1990s, stretched again, with V2500 high-bypass turbofans and an updated flight deck. The shorter, final MD-95 was renamed the Boeing 717 after McDonnell Douglas's merger with Boeing in 1997, powered by Rolls-Royce BR715 engines.

Design and development

Origins

During the 1950s Douglas Aircraft studied a short- to medium-range airliner to complement their higher capacity, long range DC-8. (DC stands for Douglas Commercial.)[2] A medium-range four-engine Model 2067 was studied but it did not receive enough interest from airlines and it was abandoned. In 1960, Douglas signed a two-year contract with Sud Aviation for technical cooperation. Douglas would market and support the Sud Aviation Caravelle and produce a licensed version if airlines ordered large numbers. None were ordered and Douglas returned to its design studies after the cooperation deal expired.[3]

.TIF.jpg)

In 1962, design studies were underway. The first version seated 63 passengers and had a gross weight of 69,000 lb (31,300 kg). This design was changed into what would be the initial DC-9 variant.[3] Douglas gave approval to produce the DC-9 on April 8, 1963.[3] Unlike the competing but larger Boeing 727 trijet, which used as many 707 components as possible, the DC-9 was an all-new design. The DC-9 has two rear-mounted Pratt & Whitney JT8D turbofan engines, relatively small, efficient wings, and a T-tail.[4] The DC-9's takeoff weight was limited to 80,000 lb (36,300 kg) for a two-person flight crew by Federal Aviation Agency regulations at the time.[3] DC-9 aircraft have five seats across for economy seating. The airplane seats 80 to 135 passengers depending on version and seating arrangement.

The DC-9 was designed for short to medium routes, often to smaller airports with shorter runways and less ground infrastructure than the major airports being served by larger designs like the Boeing 707 and Douglas DC-8. Accessibility and short field characteristics were called for. Turnarounds were simplified by built-in airstairs, including one in the tail, which shortened boarding and deplaning times.

The tail-mounted engine design facilitated a clean wing without engine pods, which had numerous advantages. For example, flaps could be longer, unimpeded by pods on the leading edge and engine blast concerns on the trailing edge. This simplified design improved airflow at low speeds and enabled lower takeoff and approach speeds, thus lowering field length requirements and keeping wing structure light. The second advantage of the tail-mounted engines was the reduction in foreign object damage from ingested debris from runways and aprons. However, with this position, the engines could ingest ice streaming off the wing roots. Third, the absence of engines in underslung pods allowed a reduction in fuselage ground clearance, making the aircraft more accessible to baggage handlers and passengers.

The problem of deep stalling, revealed by the loss of the BAC One-Eleven prototype in 1963, was overcome through various changes, including the introduction of vortilons, small surfaces beneath the wing's leading edge used to control airflow and increase low speed lift.[5]

Production

_taking_off.jpg)

The first DC-9, a production model, flew on February 25, 1965.[6] The second DC-9 flew a few weeks later,[4] with a test fleet of five aircraft flying by July. This allowed the initial Series 10 to gain airworthiness certification on November 23, 1965, and to enter service with Delta Air Lines on December 8.[6] The DC-9 was always intended to be available in multiple versions to suit customer requirements,[7] The first stretched version, the Series 30, with a longer fuselage and extended wing tips, flew on August 1, 1966, entering service with Eastern Air Lines in 1967.[6] The initial Series 10 would be followed by the improved -20, -30, and -40 variants. The final DC-9 series was the -50, which first flew in 1974.[4]

The DC-9 was a commercial success with 976 built when production ended in 1982.[4] The DC-9 is one of the longest-lasting aircraft in operation. Its last successor, the Boeing 717, was produced until 2006.

The DC-9 family was produced in 2441 units: 976 DC-9s, 1191 MD-80s, 116 MD-90s and 155 Boeing 717s.[8] This compares to 8,000 Airbus A320s delivered as of February 2018[9] and 10,000 Boeing 737s completed as of March 2018.[10]

Studies aimed at further improving DC-9 fuel efficiency, by means of retrofitted wingtips of various types, were undertaken by McDonnell Douglas. However, these did not demonstrate significant benefits, especially with existing fleets shrinking. The wing design makes retrofitting difficult.[11]

Legacy

The DC-9 was followed by the introduction of the MD-80 series in 1980. This was originally called the DC-9-80 series. It was a lengthened DC-9-50 with a higher maximum takeoff weight (MTOW), a larger wing, new main landing gear, and higher fuel capacity. The MD-80 series features a number of variants of the Pratt & Whitney JT8D turbofan engine having higher thrust ratings than those available on the DC-9. The series includes the MD-81, MD-82, MD-83, MD-88, and shorter fuselage MD-87.

The MD-80 series was further developed into the McDonnell Douglas MD-90 in the early 1990s. It has yet another fuselage stretch, an electronic flight instrument system (first introduced on the MD-88), and completely new International Aero V2500 high-bypass turbofan engines. In comparison to the very successful MD-80, relatively few MD-90s were built.

The final variant was the MD-95, which was renamed the Boeing 717-200 after McDonnell Douglas's merger with Boeing in 1997 and before aircraft deliveries began. The fuselage length and wing are very similar to those of the DC-9-30, but much use was made of lighter, modern materials. Power is supplied by two BMW/Rolls-Royce BR715 high-bypass turbofan engines.

China's Comac ARJ21 is derived from the DC-9 family. The ARJ21 is built with manufacturing tooling from the MD-90 Trunkliner program. As a consequence, it has the same fuselage cross-section, nose profile, and tail.[12]

Variants

Series 10

.jpg)

The original DC-9 (later designated the Series 10) was the smallest DC-9 variant. The -10 was 104.4 ft (31.8 m) long and had a maximum weight of 82,000 lb (37,000 kg). The Series 10 was similar in size and configuration to the BAC One-Eleven and featured a T-tail and rear-mounted engines. Power was provided by a pair of 12,500 lbf (56 kN) Pratt & Whitney JT8D-5 or 14,000 lbf (62 kN) JT8D-7 engines. A total of 137 were built. Delta Air Lines was the initial operator.

The Series 10 was produced in two main subvariants, the Series 14 and 15, although, of the first four aircraft, three were built as Series 11s and one as Series 12. These were later converted to Series 14 standard. No Series 13 were produced. A passenger/cargo version of the aircraft, with a 136-by-81-inch (3.5 by 2.1 m) side cargo door forward of the wing and a reinforced cabin floor, was certificated on March 1, 1967. Cargo versions included the Series 15MC (Minimum Change) with folding seats that can be carried in the rear of the aircraft, and the Series 15RC (Rapid Change) with seats removable on pallets. These differences disappeared over the years as new interiors were installed.[13][14]

The Series 10 was unique in the DC-9 family in not having leading-edge slats. The Series 10 was designed to have short takeoff and landing distances without the use of leading-edge high-lift devices. Therefore, the wing design of the Series 10 featured airfoils with extremely high maximum-lift capability in order to obtain the low stalling speeds necessary for short-field performance.[15]

Series 10 features

The Series 10 has an overall length of 104.4 feet (31.82 m), a fuselage length of 92.1 feet (28.07 m), a passenger-cabin length of 60 feet (18.29 m), and a wingspan of 89.4 feet (27.25 m).

The Series 10 was offered with the 14,000 lbf (62 kN)-thrust JT8D-1 and JT8D-7.[13][14] All versions of the DC-9 are equipped with an AlliedSignal (Garrett) GTCP85 APU, located in the aft fuselage.[13][14] The Series 10, as with all later versions of the DC-9, is equipped with a two-crew analog flightdeck.[13][14]

The Series 14 was originally certificated with an MTOW of 85,700 lb (38,900 kg), but subsequent options offered increases to 86,300 and 90,700 lb (41,100 kg). The aircraft's MLW in all cases is 81,700 lb (37,100 kg). The Series 14 has a fuel capacity of 3,693 US gallons (with the 907 US gal centre section fuel). The Series 15, certificated on January 21, 1966, is physically identical to the Series 14 but has an increased MTOW of 90,700 lb (41,100 kg). Typical range with 50 passengers and baggage is 950 nmi (1,760 km), increasing to 1,278 nmi (2,367 km) at long-range cruise. Range with maximum payload is 600 nmi (1,100 km), increasing to 1,450 nmi (2,690 km) with full fuel.[13][14]

The aircraft is fitted with a passenger door in the port forward fuselage, and a service door/emergency exit is installed opposite. An airstair installed below the front passenger door was available as an option as was an airstair in the tailcone. This also doubled as an emergency exit. Available with either two or four overwing exits, the DC-9-10 can seat up to a maximum certified exit limit of 109 passengers. Typical all-economy layout is 90 passengers, and 72 passengers in a more typical mixed-class layout with 12 first and 60 economy-class passengers.[13][14]

All versions of the DC-9 are equipped with a tricycle undercarriage, featuring a twin nose unit and twin main units.[13][14]

Series 20

The Series 20 was designed to satisfy a Scandinavian Airlines request for improved short-field performance by using the more-powerful engines and improved wings of the -30 combined with the shorter fuselage used in the -10. Ten Series 20 aircraft were produced, all of them the Model -21.[16]

In 1969, a DC-9 Series 20 at Long Beach was fitted with an Elliott Flight Automation Head-up display by McDonnell Douglas and used for successful three-month-long trials with pilots from various airlines, the Federal Aviation Administration, and the US Air Force.[17]

Series 20 features

The Series 20 has an overall length of 104.4 feet (31.82 m), a fuselage length of 92.1 feet (28.07 m), a passenger-cabin length of 60 feet (18.29 m), and a wingspan of 93.3 feet (28.44 m).[13][14] The DC-9 Series 20 is powered by the 15,000 lbf (67 kN) thrust JT8D-11 engine.[13][14]

The Series 20 was originally certificated at an MTOW of 94,500 lb (42,900 kg) but this was increased to 98,000 lb (44,000 kg), eight percent more than on the higher weight Series 14s and 15s. The aircraft's MLW is 95,300 lb (43,200 kg) and MZFW is 84,000 lb (38,000 kg). Typical range with maximum payload is 1,000 nmi (1,900 km), increasing to 1,450 nmi (2,690 km) with maximum fuel. The Series 20, using the same wing as the Series 30, 40 and 50, has a slightly lower basic fuel capacity than the Series 10 (3,679 US gallons).[13][14]

Series 20 milestones

- First flight: September 18, 1968.

- FAA certification: November 25, 1968.

- First delivery: December 11, 1968 to Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS)

- Entry into service: January 27, 1969 with SAS.

- Last delivery: May 1, 1969 to SAS.

Series 30

.jpg)

The Series 30 was produced to counter Boeing's 737 twinjet; 662 were built, about 60% of the total. The -30 entered service with Eastern Airlines in February 1967 with a 14 ft 9 in (4.50 m) fuselage stretch, wingspan increased by just over 3 ft (0.9 m) and full-span leading edge slats, improving takeoff and landing performance. Maximum takeoff weight was typically 110,000 lb (50,000 kg). Engines for Models -31, -32, -33, and -34 included the P&W JT8D-7 and JT8D-9 rated at 14,500 lbf (64 kN) of thrust, or JT8D-11 with 15,000 lbf (67 kN).

Unlike the Series 10, the Series 30 had leading-edge devices to reduce the landing speeds at higher landing weights; full-span slats reduced approach speeds by six knots despite 5,000 lb greater weight. The slats were lighter than slotted Krueger flaps, since the structure associated with the slat is a more efficient torque box than the structure associated with the slotted Krueger. The wing had a six-percent increase in chord, all ahead of the front spar, allowing the 15 percent chord slat to be incorporated.[18]

Series 30 versions

The Series 30 was built in four main sub-variants.[13][14]

- DC-9-31: Produced in passenger version only. The first DC-9 Series 30 flew on August 1, 1966, and the first delivery was to Eastern Airlines on February 27, 1967 after certification on December 19, 1966. Basic MTOW of 98,000 lb (44,000 kg) and subsequently certificated at weights up to 108,000 lb (49,000 kg).

- DC-9-32: Introduced in the first year (1967). Certificated March 1, 1967. Basic MTOW of 108,000 lb (49,000 kg) later increased to 110,000 lb (50,000 kg). A number of cargo versions of the Series 32 were also produced:

- 32LWF (Light Weight Freight) with modified cabin but no cargo door or reinforced floor, intended for package freighter use.

- 32CF (Convertible Freighter), with a reinforced floor but retaining passenger facilities

- 32AF (All Freight), a windowless all-cargo aircraft.

- DC-9-33: Following the Series 31 and 32 came the Series 33 for passenger/cargo or all-cargo use. Certificated on April 15, 1968, the aircraft's MTOW was 114,000 lb (52,000 kg), MLW to 102,000 lb (46,000 kg) and MZFW to 95,500 lb (43,300 kg). JT8D-9 or -11 (15,000 lbf (67 kN) thrust) engines were used. Wing incidence was increased 1.25 degrees to reduce cruise drag.[19] Only 22 were built, as All Freight (AF), Convertible Freight (CF) and Rapid Change (RC) aircraft.

- DC-9-34: The last variant was the Series 34, intended for longer range with an MTOW of 121,000 lb (55,000 kg), an MLW of 110,000 lb (50,000 kg) and an MZFW of 98,000 lb (44,000 kg). The DC-9-34CF (Convertible Freighter) was certificated April 20, 1976, while the passenger followed on November 3, 1976. The aircraft has the more powerful JT8D-9s with the -15 and -17 engines as an option. It had the wing incidence change introduced on the DC-9-33. Twelve were built, five as convertible freighters.

Series 30 features

The DC-9-30 was offered with a selection of variants of JT8D including the -1, -7, -9, -11, -15. and -17. The most common on the Series 31 is the JT8D-7 (14,000 lbf (62 kN) thrust), although it was also available with the −9 and -17 engines. On the Series 32 the JT8D-9 (14,500 lbf (64 kN) thrust) was standard, with the -11 also offered. The Series 33 was offered with the JT8D-9 or -11 (15,000 lbf (67 kN) thrust) engines and the heavyweight -34 with the JT8D-9, -15 (15,000 lbf (67 kN) thrust) or -17 (16,000 lbf (71 kN) thrust) engines.[13][14]

Series 40

.jpg)

The DC-9-40 is a further lengthened version. With a 6 ft 6 in (2 m) longer fuselage, accommodation was up to 125 passengers. The Series 40 was fitted with Pratt & Whitney engines with thrust of 14,500 to 16,000 lbf (64 to 71 kN). A total of 71 were produced. The variant first entered service with Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) in March 1968.

Series 50

The Series 50 was the largest version of the DC-9 to enter airline service. It features an 8 ft 2 in (2.49 m) fuselage stretch and seats up to 139 passengers. It entered revenue service in August 1975 with Eastern Airlines and included a number of detail improvements, a new cabin interior, and more powerful JT8D-15 or -17 engines in the 16,000 and 16,500 lbf (71 and 73 kN) class. McDonnell Douglas delivered 96, all as the Model -51. Some visual cues to distinguish this version from other DC-9 variants include side strakes or fins below the side cockpit windows, spray deflectors on the nose gear, and thrust reversers angled inward 17 degrees as compared to the original configuration. The thrust reverser modification was developed by Air Canada for its earlier aircraft, and adopted by McDonnell Douglas as a standard feature on the series 50. It was also applied to many earlier DC-9s in the course of regular maintenance.[20]

Military and government

Operators

A total of 30 DC-9 aircraft (all variants) were in commercial service as of July 2018. Operators include Aeronaves TSM (8), USA Jet Airlines (6), Everts Air Cargo (4), Ameristar Charters (4) and other operators with fewer aircraft.[21][22]

Delta Air Lines, since acquiring Northwest Airlines, has operated a fleet of DC-9 aircraft, most over 30 years old. With severe increases in fuel prices in the summer of 2008, Northwest Airlines began retiring its DC-9s, switching to Airbus A319s that are 27% more fuel efficient.[23][24] As the Northwest/Delta merger progressed, Delta returned several stored DC-9s to service. Delta Air Lines made its last DC-9 commercial flight from Minneapolis/St. Paul to Atlanta on January 6, 2014 with the flight number DL2014.[25][26]

With the existing DC-9 fleet shrinking, modifications do not appear to be likely to occur, especially since the wing design makes retrofitting difficult.[11] DC-9s are therefore likely to be further replaced in service by newer airliners such as Boeing 737, Airbus A320, Embraer E-Jets, and the Bombardier CSeries.[27]

One ex-SAS DC-9-21 is operated as a skydiving jump platform at Perris Valley Airport in Perris, California. With the steps on the ventral stairs removed, it is the only airline transport class jet certified to date by the FAA for skydiving operations as of 2016.[28]

Deliveries

| Type | Total | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | 1973 | 1972 | 1971 | 1970 | 1969 | 1968 | 1967 | 1966 | 1965 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC-9-10 | 113 | 10 | 29 | 69 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| DC-9-10C | 24 | 4 | 20 | ||||||||||||||||

| DC-9-20 | 10 | 9 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| DC-9-30 | 585 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 24 | 1 | 12 | 16 | 21 | 21 | 17 | 42 | 41 | 97 | 161 | 101 | |||

| DC-9-30C | 30 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 3 | ||||||||||

| DC-9-30F | 6 | 4 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| DC-9-40 | 71 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 27 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 10 | |||||||

| DC-9-50 | 96 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 28 | 15 | |||||||||||

| C-9A | 21 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 7 | ||||||||||||||

| C-9B | 17 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |||||||||||||

| VC-9C | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Total | 976 | 10 | 16 | 18 | 39 | 22 | 22 | 50 | 42 | 48 | 29 | 32 | 46 | 51 | 122 | 202 | 153 | 69 | 5 |

Accidents and incidents

As of June 2018, the DC-9 has been involved in 276 aviation occurrences, including 145 hull-loss accidents,[30] with 3,697 fatalities combined.[31]

Notable accidents

- On October 1, 1966, West Coast Airlines Flight 956 crashed with eighteen fatalities and no survivors. This accident marked the first loss of a DC-9.[32]

- On March 9, 1967, TWA Flight 553 fell to the field in Concord Township, near Urbana, Ohio, following a mid-air collision with a Beechcraft Baron, an accident that triggered substantial changes in air traffic control procedures.[33] All 25 people on board the DC-9 were killed.

- On March 16, 1969, Viasa Flight 742, a DC-9-32, crashed into the La Trinidad neighborhood of Maracaibo, Venezuela, during a failed take-off. All 84 people on board the aircraft, as well as 71 people on the ground, were killed. With 155 dead in all, this was the deadliest crash involving a member of the original DC-9 family, as well as the worst crash in aviation history at the time it took place.[34]

- On June 27, 1969, Douglas DC-9-31 N906H of Hawaiian Airlines was struck on the ground by Vickers Viscount N7410 of Aloha Airlines at Honolulu International Airport. The Viscount was damaged beyond repair. The DC-9 was repaired and flew with Hughes Airwest, Republic Airlines, and Northwest Airlines until 2002.[35]

- On September 9, 1969, Allegheny Airlines Flight 853, a DC-9-30, collided in mid-air with a Piper PA-28 Cherokee near Fairland, Indiana. The DC-9 carried 78 passengers and four crew members, the Piper, one pilot. The occupants of both aircraft were killed in the accident and the aircraft were destroyed.[36][37]

- On February 15, 1970, a Dominicana de Aviación DC-9 crashed after taking off from Santo Domingo, in what is known as the Dominicana DC-9 air disaster. The crash, possibly caused by contaminated fuel, killed all 102 passengers and crew, including champion boxer Teo Cruz.[38][39]

- On May 2, 1970, an Overseas National Airways DC-9, wet-leased to ALM Dutch Antilles Airlines and operating as ALM Flight 980, ditched in the Caribbean Sea on a flight from New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport to Princess Juliana International Airport on Saint Maarten. After three landing attempts in poor weather at Saint Maarten, the pilots began to divert to their alternate of Saint Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands but ran out of fuel 30 mi (48 km) short of the island. After about ten minutes, the aircraft sank in 5,000 ft (1524 m) of water and was never recovered. 40 people survived the ditching; 23 perished.[40]

- On November 14, 1970, Southern Airways Flight 932, a DC-9, crashed into a hill near Tri-State Airport in Huntington, West Virginia. All 75 on board were killed (including 37 members of the Marshall University Thundering Herd football team, eight members of the coaching staff, 25 boosters, and others).

- On June 6, 1971, Hughes Airwest Flight 706 was involved in a midair collision with a United States Marine Corps F-4 Phantom fighter jet. All 49 people on board the DC-9 died; one of two aboard the USMC aircraft ejected and survived.

- On January 21, 1972, a Turkish Airlines DC-9-32 TC-JAC diverted to Adana, Turkey after pressurization problems. The aircraft hit the ground during downwind on the 2nd approach and caught fire. There was one fatality.

- On January 26, 1972, JAT Flight 367 from Stockholm to Belgrade, DC-9-32 registration YU-AHT, was destroyed in flight by a bomb placed on board. The sole survivor was a flight attendant, Vesna Vulović, who holds the record for the world's longest fall without a parachute when she fell some 33,000 ft (10,000 m) inside a section of the airplane and survived.

- On November 10–11, 1972, Southern Airways Flight 49 was hijacked while departing Birmingham, Alabama's airport by three armed men. The hijackers then proceeded to fly the passengers and crew to multiple locations in the United States, Canada, and Cuba, including Chattanooga, Tennessee, where the less-than-demanded ransom money was delivered, the now-defunct McCoy Air Force Base in Orlando, Florida, where the FBI shot out two of the DC-9's four main landing wheels, and Havana, where the 30-hour and 4,000 miles (6,400 km) odyssey came to an end with no fatalities or injuries among the passengers and crew members. This incident is notable for being the first hijacking in which an aircraft left Cuba with the hijackers on board.[41]

- On December 20, 1972, North Central Airlines Flight 575, DC-9-31 registration N954N, collided during its takeoff roll with Delta Air Lines Flight 954, a Convair CV-880 that was taxiing across the same runway at O'Hare International Airport in Chicago, Illinois. The DC-9 was destroyed, killing 10 and injuring 15 of the 45 people on board; two people among the 93 aboard the Convair 880 suffered minor injuries.[42]

- On 5 March 1973, an Iberia Flight 504 DC-9 flying from Palma de Mallorca to London collided in mid-air with a Spantax Flight 400 Convair 990 flying from Madrid to London. All 68 people on board the DC-9 were killed. The CV-990 made a successful emergency landing at Cognac – Châteaubernard Air Base.

- On July 31, 1973, Delta Air Lines Flight 723, DC-9-31 registration N975NE, crashed into a seawall at Logan International Airport in Boston, Massachusetts, killing all 83 passengers and 6 crew members on board. One of the passengers initially survived the accident but later died in a hospital.

- On September 11, 1974, Eastern Air Lines Flight 212, a DC-9-30 crashed just short of the runway at Charlotte, North Carolina, killing 71 out of the 82 occupants.

- On October 30, 1975, an Inex-Adria Aviopromet DC-9-32 hit high ground during an approach in fog near Prague-Suchdol, Czechoslovakia. 75 people were killed.[43]

- On September 10, 1976, an Inex-Adria Aviopromet DC-9-31 collided with a British Airways Trident over the Croatian town of Vrbovec, killing all 176 people aboard both aircraft and another person on the ground, in what is known as the 1976 Zagreb mid-air collision.

- On April 4, 1977, Southern Airways Flight 242, a DC-9-31, lost engine power while flying through a severe thunderstorm before crash landing onto a highway in New Hope, Georgia, striking roadside buildings. The crash and fire resulted in the death of both flight crew and 61 passengers. Nine people on the ground also died. Both flight attendants and 20 passengers survived.[44][45]

- On June 26, 1978, Air Canada Flight 189, a DC-9 overran the runway in Toronto after a blown tire aborted the takeoff. Two of the 107 passengers and crew were killed.[46]

- On September 14, 1979, Aero Trasporti Italiani Flight 12, a DC-9-32 crashed in the mountains near Cagliari, Italy while approaching Cagliari-Elmas Airport. All 27 passengers and 4 crew members died in the crash and ensuing fire.[47]

- On June 27, 1980, Itavia Flight 870, a DC-9-15, broke up mid-air and crashed into the sea near the Italian island of Ustica. All 81 people on board were killed. The cause has been the subject of a decades-long controversy, with either a terrorist bomb on board or an accidental shootdown during a military operation blamed for the accident.

- On July 27, 1981, Aeroméxico Flight 230, a DC-9 ran off the runway in Chihuahua. Bad weather and pilot error were blamed.

- On June 2, 1983, Air Canada Flight 797, a DC-9 experienced an electrical fire in the aft lavatory during flight, resulting in an emergency landing at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. During evacuation, the sudden influx of oxygen caused a flash fire throughout the cabin, resulting in the deaths of 23 of the 41 passengers, including Canadian folk singer Stan Rogers. All five crew members survived.

- On December 7, 1983, the Madrid runway disaster took place where a departing Iberia Boeing 727 struck an Aviaco Douglas DC-9 causing the death of 93 passengers and crew. All 42 passengers and crew on board the DC-9 were killed.

- On September 6, 1985, Midwest Express Airlines Flight 105, operated with a DC-9-14, crashed just after takeoff from General Mitchell International Airport in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The crash was caused by improper control inputs by the flight crew after the number 2 engine failed, and all 31 aboard were killed.

- On August 31, 1986, Aeroméxico Flight 498 collided in mid-air with a Piper Cherokee over the city of Cerritos, California, then crashed into the city, killing all 64 aboard the aircraft, 15 people on the ground, and all three in the small plane.

- On April 4, 1987, Garuda Indonesia Flight 035, a DC-9-32, hit a pylon and crashed on approach to Polonia International Airport in bad weather with 24 fatalities.[48]

- On November 15, 1987, Continental Airlines Flight 1713, a DC-9-14, crashed on takeoff from Stapleton International Airport in bad weather with 28 fatalities. This accident was attributed to a combination of confusion at the ATC, exceeding allowed time-limit for takeoff after de-icing the wings, and inexperienced crew.

- On November 14, 1990, Alitalia Flight 404, a DC-9-32, crashed into a hillside on approach to Zurich Airport, killing all 46 persons on board. The crash was caused by a short circuit, which led to a failure of the aircraft's NAV receiver and GPWS system.

- On December 3, 1990, Northwest Airlines Flight 1482, a DC-9-14, taxied onto the wrong taxiway in dense fog at Detroit-Metropolitan Wayne County Airport, Michigan. It entered the active runway instead of the taxiway instructed by air traffic controllers. It was then struck by a departing Boeing 727. Nine people were killed.[49][50]

- On March 5, 1991, Aeropostal Alas de Venezuela Flight 108, a DC-9-32, crashed into a mountainside in Trujillo State, Venezuela, killing all 40 passengers and five crew aboard.

- On April 18, 1993, Japan Air System Flight 451, a DC-9-41 JA8448 crashed while landing at Hanamaki Airport in Japan. There were 19 injuries, though all 77 aboard survived. The aircraft was written off.[51]

- On June 21, 1993, Garuda Indonesia Flight 630, a DC-9-32 PK-GNT landed heavily on runway 09 (forces of 5g) and taxied safely to apron at Ngurah Rai International Airport in Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia. Major structural damage was discovered there. The aircraft was high on approach, which was overcorrected, causing the aircraft coming too low. Thrust was increased and the DC-9 then struck the runway in a nose up attitude. All passenger and crew aboard survived.

- On July 2, 1994, USAir Flight 1016, a DC-9-31 N954VJ crashed in Charlotte, North Carolina while performing a go-around because of heavy storms and wind shear at the approach of runway 18R. There were 37 fatalities and 15 injured among the passengers and crew. Although the airplane came to rest in a residential area with the tail section striking a house, there were no fatalities or injuries on the ground.

- On May 11, 1996, ValuJet Flight 592, a DC-9-32 N904VJ crashed in the Florida Everglades due to a fire caused by the activation of chemical oxygen generators illegally stored in the hold. The fire damaged the plane's electrical system and eventually overcame the crew, resulting in the deaths of all 110 people on board.

- On October 10, 1997, Austral Flight 2553, a DC-9-32 registration LV-WEG, en route from Posadas to Buenos Aires, crashed near Fray Bentos, Uruguay, killing all 69 passengers and five crew on board.[52]

- On February 2, 1998, Cebu Pacific Flight 387, a DC-9-32 RP-C1507 crashed on the slopes of Mount Sumagaya in Misamis Oriental, Philippines, killing all 104 passengers and crew on board. Aviation investigators deemed the incident to be caused by pilot error when the plane made a non-regular stopover to Tacloban.

- On November 9, 1999, TAESA Flight 725 crashed a few minutes after leaving the Uruapan Airport en route to Mexico City. 18 people were killed in the accident.[53]

- On October 6, 2000, Aeroméxico Flight 250, a DC-9-31 en route from Mexico City to Reynosa, Mexico, could not stop at the end of the runway and crashed into houses and fell into a small canal. Four people on the ground were killed. None of 83 passengers and 5 crew members were killed. The DC-9 was heavily damaged and classified as a loss. The runway had seen heavy rainfall as a result of Hurricane Keith.[54]

- On May 10, 2005, a Northwest Airlines DC-9-50 collided on the ground with a Northwest Airlines Airbus A319 that had just pushed back from the gate at Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport after losing its steering ability. The DC-9 suffered a malfunction in one of its hydraulic systems in flight. After landing, the captain shut down one of the plane's engines, inadvertently disabling the remaining working hydraulic system. Six people were injured and both planes were substantially damaged.[55]

- On 10 December 2005, Sosoliso Airlines Flight 1145 from Abuja crash-landed at Port Harcourt International Airport, Nigeria. There were 108 fatalities and two survivors.

- On April 15, 2008, Hewa Bora Airways Flight 122 crashed into a residential neighborhood, in the Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo,[56] resulting in the deaths of at least 44 people.[57]

- On July 6, 2008, USA Jet Airlines Flight 199, a DC-9-15F, crashed on approach to Saltillo, Mexico, after a flight from Shreveport, Louisiana. The captain died and first officer was seriously injured.[58]

Aircraft on display

- CF-TLL (cn 47021) – DC-9-32 on static display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.[59] It was previously operated by Air Canada.[60]

- N292L (cn 47174) - DC-9-32 nose section displayed inside Schiphol International Airport. Painted in KLM livery although the plane never served with the airline. It was previously used by TWA and Delta Airlines.[61][62]

- EC-BQZ (cn 47456) – DC-9-32 on static display at Adolfo Suárez Madrid–Barajas Airport in Madrid.[63]

- MM62012 (cn 47595) – DC-9-32 on static display at Volandia in Somma Lombardo, Varese. This aircraft was operated by the Italian Air Force as a VIP transport, carrying the president of Italy among other duties.[64][65][66]

- N675MC (cn 47651) – DC-9-51 on static display at the Delta Flight Museum at Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport in Atlanta, Georgia.[67] It arrived at the museum on 27 April 2014.[68] It was previously operated by Delta Air Lines.[69]

- PK-GNC (cn 47481) - DC-9-32 painted in Garuda Indonesia's 1960s livery and put on display inside GMF hangar in Soekarno-Hatta Airport.[70][71]

- PK-GNT (cn 47790) – DC-9-32 on static display at the Transportation Museum in Taman Mini Indonesia Indah in Jakarta, Indonesia.[72] It was relegated to display status after suffering heavy damage in a landing accident in 1993.[73] It was previously operated by Garuda Indonesia.[74]

- N779NC (cn 48101) – DC-9-51 was on static display at the Carolinas Aviation Museum at Charlotte Douglas International Airport in Charlotte, North Carolina until it was scrapped in January 2017.[75][76] Its ferry flight to Charlotte was the last scheduled passenger DC-9 flight in the United States.[77] It was previously operated by Delta Air Lines.[78]

- XA-JEB - Ex Aeromexico DC-9-32 on display at a park in Cadereyta de Montes, Querétaro, Mexico. Formerly Hugh Hefner's private jet, the 'Big Bunny', XA-JEB was sold in 1975 to Venezuela Airlines, who later sold it to Aeromexico, where it was operated until 2004. It was sold and placed on display in 2008 for use as an educational tool.[79]

Specifications

| Variant | -15 (-21) | -32 | -41 | -51 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew[81]:66 | Two | |||

| 1-class seating:15–18 | 90Y@31-32" | 115Y@31-33" | 125@31-34" | 135@32-33" |

| Exit limit[81]:80 | 109 | 127 | 128 | 139 |

| Cargo:4 | 600 ft³ / 17.0m³ -15F: 2,762 ft³ / 78.2m³ |

895 ft³ / 25.3m³ -33F: 4,195 ft³ / 119.0m³ |

1,019 ft³ / 28.9m³ | 1,174 ft³ / 33.2m³ |

| Length:5–9 | 104 ft 4.8in / 31.82m | 119 ft 3.6in / 36.36m | 125 ft 7.2in / 38.28m | 133 ft 7in / 40.72m |

| Wingspan:10–14 | 89 ft 4.8in / 27.25m -21: 93 ft 3.6in / 28.44m |

93 ft 3.6in / 28.44m | 93 ft 4.2in / 28.45m | |

| Height:10–14 | 27 ft 7in / 8.4m | 27 ft 9in / 8.5m | 28 ft 5in / 8.7m | 28 ft 9in / 8.8m |

| Fuselage width:23 | 131.6in / 334.3 cm | |||

| Cabin width:24 | 122.4in / 311cm | |||

| Max. takeoff:4 | 90,700 lb / 41,141 kg -21: 98,000 lb / 45,359 kg |

108,000 lb / 48,988 kg | 114,000 lb / 51,710 kg | 121,000 lb / 54,885 kg |

| Max. Landing:4 | 81,700 lb (37,058 kg) -21: 95,300 lb (43,227 kg) |

99,000 lb (44,906 kg) | 102,000 lb (46,266 kg) | 110,000 lb (49,895 kg) |

| Empty:4 | 49,162 lb / 22,300 kg -15F: 53,200 lb / 24,131 kg -21: 52,644 lb / 23,879 kg |

56,855 lb / 25,789 kg -33F: 56,430 lb / 25,596 kg |

61,335 lb / 27,821 kg | 64,675 lb / 29,336 kg |

| Fuel:4 | 24,743 lb / 11,223 kg | 24,649 lb / 11,181 kg | ||

| Engine (2×)[81] | JT8D-1/5/7/9/11/15/17 -21: -9/11 |

-1/5/7/9/11/15/17 | -9/11/15/17 | -15/17 |

| Thrust (2×)[81] | -1/7: 14,000 lbf (62 kN), -5/-9: 12,250 lbf (54.5 kN), -11: 15,000 lbf (67 kN), -15: 15,500 lbf (69 kN), -17: 16,000 lbf (71 kN) | |||

| Ceiling[81]:67 | 35,000 ft (11,000 m) | |||

| MMo[81] | Mach 0.84 (484 kn; 897 km/h) | |||

| Range:36–45 | 1,300 nmi (2,400 km) -21: 1,500 nmi (2,800 km) |

1,500 nmi (2,800 km) | 1,200 nmi (2,200 km) | 1,300 nmi (2,400 km) |

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- BAC One-Eleven

- Boeing 737

- Fokker F28 Fellowship

- Dassault Mercure

- Sud Aviation Caravelle

- Tupolev Tu-134

Related lists

References

Citations

- "Airliner price index". Flight International. 10 August 1972. p. 183.

- "DC-1 Commercial Transport". Boeing. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- Endres, Gunter. McDonnell Douglas DC-9/MD-80 & MD-90. London: Ian Allan, 1991. ISBN 0-7110-1958-4.

- Norris, Guy and Mark Wagner. "DC-9: Twinjet Workhorse". Douglas Jetliners. MBI Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-7603-0676-1.

- "The DC-9 and the Deep Stall". Flight International: 442. 25 March 1965. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- Air International June 1980, p. 293.

- Air International June 1980, p. 292.

- "Orders & Deliveries". Boeing.

- Max Kingsley-Jones (23 Feb 2018). "Airbus completes 8,000th A320 family delivery". Flightglobal.

- Max Kingsley-Jones (13 March 2018). "How Boeing built 10,000 737s". Flightglobal.

- Assessment of Wingtip Modifications to Increase the Fuel Efficiency of Air Force Aircraft. The National Academies Press. 2007. p. 40. ISBN 0-309-10497-1.

- Burchell, Bill. "Setting Up Support For Future Regional Jets". Aviation Week, October 13, 2010.

- Airclaims Jet Programs 1995

- Jane's Civil and Military Aircraft Upgrades 1995

- Shevell, Richard S. and Schaufele, Roger D., "Aerodynamic Design Features of the DC-9", AIAA paper 65-738, presented at the AIAA/RAeS/JSASS Aircraft Design and Technology Meeting, Los Angeles California, November 1965. Reprinted in the AIAA Journal of Aircraft, Vol.3 No.6, November/December 1966, pp.515–523.

- "Boeing: Commercial". active.boeing.com.

- "Air Transport: Head-Up Demonstration". Flight International, Volume 95, No. 3125, 30 January 1969. p. 159.

- Schaufele, Roger D. and Ebeling, Ann W., "Aerodynamic Design of the DC-9 Wing and High-Lift System", SAE paper 670846, presented at the Aeronautic & Space Engineering and Manufacturing Meeting, Los Angeles California, October 1967.

- Waddington, Terry, McDonnell Douglas DC-9; Great Airliners Series, Volume Four, World Transport Press, Inc., 1998, p.126. ISBN 978-0-9626730-9-2.

- http://www.airlinercafe.com/page.php?id=396%5B%5D

- "Aircraft Quick Search". ch-aviation.ch. Retrieved 9 Aug 2013.

- "World Airline Census 2018". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- "To Save Fuel, Airlines Find No Speck Too Small". New York Times, June 11, 2008.

- Soaring Fuel Prices Pinch Airlines Harder, Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2008, p. B1.

- Trejos, Nancy (January 7, 2014). "Delta DC-9 aircraft makes final flight". USA Today. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- "Delta retires last DC-9 - CNN.com". CNN. January 7, 2014.

- "Bombardier Launches CSeries Jet". New York Times, July 13, 2008.

- Perris Valley Skydiving DC-9 Video

- Order and Deliveries – User Defined Reports. Boeing

- Accident summary hull-losses Douglas DC-9, Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- fatality statistics Douglas DC-9. Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- National Transportation Safety Board (1967-12-11). "Aircraft Accident Report. West Coast Airlines, Inc DC-9 N9101. Near Wemme, Oregon" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- National Transportation Safety Board (1968-06-19). "Aircraft Accident Report. Trans World Airlines, Inc., Douglas DC-9, Tann Company Beechcraft Baron B-55 In-flight Collision near Urbana, Ohio, March 9, 1967" (PDF). AirDisaster.Com. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- "DISASTERS: The Worst Ever". 9 August 1971 – via content.time.com.

- "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- NTSB Report (PDF) Archived 2008-12-18 at the Wayback Machine

- McGlaun, Dan. "Allegheny 853 Crash Site Pictures". www.mcglaun.com. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- D. Gero (2005-05-21). "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 HI-177 Santo Domingo". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- "Former Champ Teo Cruz Dies in Plane Crash". Modesto Bee. Modesto, California. Associated Press. 1970-02-16. p. A-6. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- National Transportation Safety Board (1971-03-31). "Aircraft Accident Report: Overseas National Airways, Inc., operating as Antilliaanse Luchtvaart Maatschappij Flight 980, near St. Croix, VirginIslands, May 2, 1970. DC-9 N935F" (PDF). AirDisaster.Com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Mickolus, Edward F.; Susan L. Simmons (2011). The Terrorist List. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-313-37471-5. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- "National Transportation Safety Board Report Number NTSB-AAR-73-15 "Aircraft Accident Report North Central Airlines, Inc., McDonnell Douglas DC-9-31, N954N, and Delta Air Lines, Inc., Convair CV-880, N8807E, O'Hare International Airport, Chicago, Illinois, December 20, 1972," adopted July 5, 1973" (PDF).

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 YU-AJO Praha-Ruzyne International Airport (PRG)". aviation-safety.net.

- National Transportation Safety Board (1978-01-26). "Aircraft Accident Report: Southern Airways, Inc. DC-9-31, N1335U. New Hope, Georgia. April 4, 1977" (PDF). AirDisaster.Com. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Vanderbilt, Tom (2010-03-12). "When Planes Land on Highways: The ins and outs of a surprisingly frequent phenomenon". Slate.

- Priest, Lisa; Rick Cash (2005-03-08). "Takeoffs and landings always pose risk of calamity, as history shows" (Fee required.). The Globe and Mail. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

The last time an aircraft skidded off the runway in Toronto, seriously injuring passengers, was more than a quarter-century ago. On June 26, 1978, an Air Canada DC-9 skidded off a taxi strip at Toronto International Airport (what is today Pearson International Airport) during an aborted takeoff, then belly-flopped into a swampy ravine, killing two passengers and injuring more than a hundred others.

- "ASN Aircraft Accident description of the 14 SEP 1979 accident of a McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 I-ATJC at Sarroch". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. February 21, 2006. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- "ASN Aircraft accident Douglas DC-9-14 N3313L Detroit-Metropolitan Wayne County Airport, Michigan (DTW)". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. 2008-11-23. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- National Transportation Safety Board (1991-06-25). "Aircraft Accident Report: Northwest Airlines Inc. Flights 1482 & 299, Runway Incursion and Collision, Detroit Metropolitan/Wayne County Airport, Romulus, Michigan, December 3, 1990" (PDF). AirDisaster.Com. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-41 JA8448 Morioka-Hanamaki Airport (HNA)". aviation-safety.net.

- "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 LV-WEG Nuevo Berlin". Aviation Safety Network. 24 February 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-9-31F XA-TKN Uruapan." Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on July 4, 2010.

- "06 Oct 2000 accident entry." Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on March 23, 2011.

- "NTSB: Pilot caused airport collision". Twincities.com. 2007-03-05. Retrieved 2015-04-05.

- "Plane crashes into African marketplace" Archived April 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. CNN, April 15, 2008.

- "Toll from Congo plane crash rises to 44". Associated Press, 2008-04-17

- USA Jet Flight 199. aviation-safety.net

- "MCDONNELL DOUGLAS DC-9-32". Canada Aviation and Space Museum. Canada Science and Technology Museums Corporation. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "C-FTLL Air Canada McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 - cn 47021 / 133". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Irish251 (2013-03-10), N929L DC-9-32 "City of Schiphol", retrieved 2019-12-26

- "N3333L | McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 | Delta Air Lines | George W. Hamlin". JetPhotos. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- "EC-BQZ Iberia McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 - cn 47456 / 580". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "IL DC9 PRESIDENZIALE A PORTATA DI MANO". Volandia (in Italian). 29 October 2016. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Portion of Historic DC-9 Donated to Volandia Museum". Warbirds News. Warbirds News. 5 April 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "MM62012 Aeronautica Militare (Italian Air Force) McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 - cn 47595 / 709". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "McDonnell Douglas DC-9 Ship 9880". Delta Flight Museum. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Meng, Tiffany (28 April 2014). "Two new planes". Delta Flight Museum. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "N675MC Delta Air Lines McDonnell Douglas DC-9-51 - cn 47651 / 780". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "PK-GNC | McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 | Garuda Indonesia | Firat Cimenli". JetPhotos. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- Nurhalim, Rendy (2017-10-27). "Ada DC-9 Berlivery Klasik di Hanggar Garuda Maintenance Facility, Buat Apa Ya?". KabarPenumpang.com. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- "Museum Transportasi". tmii (in Indonesian). Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "PK-GNT Garuda Indonesia McDonnell Douglas DC-9-32 - cn 47790 / 907". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "Delta Air Lines last DC-9, N779NC". Carolinas Aviation Museum. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "N779NC Delta Air Lines McDonnell Douglas DC-9-50". Planespotters.net. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- Washburn, Mark (23 January 2014). "Delta's last DC-9 retires at Charlotte museum". CharlotteObserver.com. The McClatchy Company. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- "N779NC Delta Air Lines McDonnell Douglas DC-9-51 - cn 48101 / 931". Planespotters.net. Planespotters.net. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Svetkey, Benjamin. "The Rise and Fall of the Big Bunny: What Happened to Hugh Hefner's Private Jet". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- "DC-9 airplane characteristics for airport planning" (PDF). Douglas aircraft company. June 1984.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet no. A6WE" (PDF). FAA. March 25, 2014.

Bibliography

- Becher, Thomas. Douglas Twinjets, DC-9, MD-80, MD-90 and Boeing 717. Ramsbury, Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press, 2002. ISBN 978-1-8612-6446-6.

- "Super 80 For the Eighties". Air International, Vol 18 No 6, June 1980. pp. 267–272, 292–296. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1966–67. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1966.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1976–77. London: Jane's Yearbooks, 1976. ISBN 0-354-00538-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- DC-9 page on Boeing.com

- "DC-9 history page on Boeing.com". Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- DC-9-10/20/30 on Airliners.net and DC-9-40/50 on Airliners.net

- DC-9 History on AviationHistoryOnline.com

- DC-9 tag on aviationtag.com