Bradley International Airport

Bradley International Airport (IATA: BDL, ICAO: KBDL, FAA LID: BDL) is a public international airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut. Owned and operated by the Connecticut Airport Authority,[2] it is the second-largest airport in New England.[3]

Bradley International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Connecticut Airport Authority | ||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Connecticut Airport Authority | ||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Hartford, Springfield | ||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Windsor Locks, Connecticut, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 173 ft / 53 m | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 41°56′21″N 072°41′00″W | ||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||

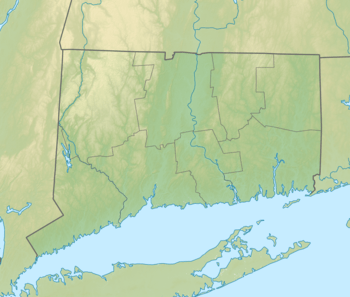

| Map | |||||||||||||||||||

BDL  BDL | |||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The airport is about halfway between Hartford and Springfield. It is Connecticut's busiest commercial airport and the second-busiest airport in New England after Boston's Logan International Airport, with over 6.75 million passengers in 2019.[1] The four largest carriers at Bradley International Airport are Southwest, Delta, JetBlue, and American with market shares of 29%, 19%, 15%, and 14%, respectively.[4] As a dual-use military facility with the U.S. Air Force, the airport is home to the 103d Airlift Wing (103 AW) of the Connecticut Air National Guard.

In 2017 Bradley was the 53rd-busiest airport in the United States, by passengers enplaned.[5] Bradley was originally branded as the "Gateway to New England" and is home to the New England Air Museum. In 2016 Bradley International launched its new brand, "Love The Journey".[6]

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems for 2017–2021 categorized it as a medium-hub primary commercial service facility.[7]

The former discount department store chain Bradlees was named after the airport as many of the early planning meetings were held there.[8]

History

20th century

Bradley has its origins in the 1940 acquisition of 1,700 acres (690 ha) of land in Windsor Locks by the state of Connecticut. In 1941, this land was turned over to the U.S. Army, as the country began its preparations for the impending war.[9]

The airfield was named after 24-year-old Lt. Eugene M. Bradley of Antlers, Oklahoma, assigned to the 64th Pursuit Squadron, who died when his P-40 crashed during a dogfight training drill on August 21, 1941.[10]

The airfield began civil use in 1947 as Bradley International Airport. Its first commercial flight was Eastern Air Lines Flight 624. International cargo operations at the airport also began that year. Bradley eventually replaced the older, smaller Hartford–Brainard Airport as Hartford's primary airport.[9]

In 1948 the federal government deeded the Airport to the State of Connecticut for public and commercial use.[9]

In 1950 Bradley International Airport exceeded the 100,000-passenger mark, handling 108,348 passengers.[9] In 1952 the Murphy Terminal opened. Later dubbed Terminal B, the terminal was the oldest passenger terminal in the US when it closed in 2010.[11]

The April 1957 OAG shows 39 weekday departures: 14 American, 14 Eastern, 9 United, and 2 Northeast. The first jets were United 720s to Cleveland in early 1961. Nonstops never reached west of Chicago or south of Washington until Eastern and Northeast began nonstops to Miami in 1967; nonstops to Los Angeles and Atlanta started in 1968.

In 1960, Bradley handled 500,238 passengers.[9]

In 1971, the Murphy Terminal was expanded with an International Arrivals wing. This was followed by the installation of instrument landing systems on two runways in 1977.

In 1976 an experimental monorail was completed from the terminal to a parking lot 7/10 of a mile away. The "people mover" cost US$4 million and was anticipated to cost $250,000 annually to operate. Due to the high operating cost, the monorail was never put in service and was dismantled in 1984 to make room for a new terminal building.[12][13] The retired vehicles from the system are now on display at the Connecticut Trolley Museum in East Windsor, Connecticut.[14]

In 1979 the "Windsor Locks" tornado ripped through the eastern portions of the airport. The New England Air Museum sustained some of the worst damage. It reopened in 1981.[15]

The new Terminal A and Bradley Sheraton Hotel were completed in 1986. The Roncari cargo terminal was also built.[9]

21st century

2001 saw the commencement of the Terminal Improvement Project to expand Terminal A with a new concourse, construct a new International Arrivals Building and centralize passenger screening. The airport expansion was part of a larger project to enhance the reputation of the Hartford metropolitan area as a destination for business and vacation travel. The new East Concourse, designed by HNTB, opened in September 2002.[9]

In December 2002 a new International Arrivals Building opened west of Terminal B,[9] housing the Federal Inspection Station with one jetway.[16] Two government agencies support the facility; U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The FIS Terminal can process more than 300 passengers per hour from aircraft as large as a Boeing 747. This facility cost approximately $7.7 million, which included the building and site work, funded through the Bradley Improvement Fund. Currently the International Arrivals Building is utilized by Delta Air Lines and Frontier Airlines (Apple Vacations) for their seasonal service to Cancun, Mexico and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic.[17] All international arrivals except for those from airports with customs preclearance are processed through the IAB. International departures are handled from the existing terminal complex.

On October 2–3, 2007 the Airbus A380 visited Bradley on its world tour, stopping in Hartford to showcase the aircraft to Connecticut workers for Pratt & Whitney and Hamilton Sundstrand, both divisions of United Technologies, which helped build the GP7000 TurboFan engines, which is an option to power the aircraft. Bradley Airport is one of only 68 airports worldwide large enough to accommodate the A380. No carriers provide regular A380 service to Bradley, but the airport occasionally is a diversion airfield for JFK-bound A380s.[18]

On October 7, 2008 Embraer, an aerospace company based in Brazil, selected Bradley as its service center for the Northeastern United States. An $11 million project was begun with support from teams of the Connecticut Department of Transportation and Connecticut's Economic and Community Development. The center is intended to be a full maintenance and repair facility for its line of business jets and is expected to employ up to 60 aircraft technicians. The facility was temporarily closed ten months after opening due to economic conditions, reopening on February 28, 2011.[19][20]

On June 22, 2012 the Connecticut Airport Authority board approved the hiring of Kevin A. Dillon as the Executive Director for the Connecticut Airport Authority, including Bradley International Airport.[21]

On October 21, 2015 Bradley announced renewed transatlantic service, partnering with Aer Lingus to bring daily flights between Bradley and Dublin.[22][23] Service to Dublin began on September 28, 2016. On September 13, 2018 Governor Dannel P. Malloy announced that Aer Lingus service at Bradley International Airport will continue for at least four more years under a new agreement made with the state, committing the airline to continue its transatlantic service at the airport through September 2022. Aer Lingus committed to placing one of its first four A321neoLR aircraft on the Bradley to Dublin route.[24]

Norwegian Air Shuttle flew the airport's second transatlantic European flight. The first flight was on June 17, 2017 to Edinburgh in the UK. On January 15, 2018 the airline announced it would end service from Bradley to Scotland, with the last flight leaving March 25, 2018.[25]

The owners of TAP Portugal, a consortium headed by David Neeleman, have expressed interest in starting a direct route between Lisbon and Bradley International.[26]

On January 25, 2017 Spirit Airlines announced new daily nonstop service to Orlando and Fort Lauderdale along with 4 times weekly seasonal service to Myrtle Beach. The first flight to Orlando was on April 27,[27] and service to Fort Lauderdale started on June 16.[28] The same day,[28] the company also announced seasonal nonstop service to Fort Myers and Tampa, which began on November 9, 2017.[29][30]

Facilities

Bradley International Airport covers 2,432 acres (984 ha) at an elevation of 173 feet (53 m). It has three asphalt runways: 6/24 is 9,510 by 200 feet (2,899 × 61 m); 15/33 is 6,847 by 150 feet (2,087 × 46 m); 1/19 is 4,269 by 100 feet (1,301 × 30 m).[2]

In the year ending March 31, 2016 the airport had 93,678 aircraft operations, averaging 257 per day: 61% airline, 21% air taxi, 16% general aviation and 3% military. Sixty-four aircraft were then based at this airport: 48% jet, 31% military, 3% multi-engine, 11% helicopter and 6% single-engine.[2]

Terminals

The airport has one terminal with two concourses: East Concourse (Gates 1–12) and West Concourse (Gates 20–30) The East Concourse (Gates 1–12) houses Aer Lingus, Air Canada, Delta, JetBlue and Southwest. While the West Concourse (Gates 20–30) houses American, Frontier, Spirit and United.

The third floor of terminal A has the administrative offices of the Connecticut Airport Authority.[31]

Former terminal

Terminal B, known as the Murphy Terminal, opened in 1952 and was closed to passenger use in 2010. It was slowly demolished starting in late 2015 and ending in early 2016. It housed the administrative offices of the CAA and TSA until its demolition.

The Customs Building that is used for arriving international flights has been dubbed Terminal B until a new Terminal B with 24 gates is rebuilt.

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

Cargo

| Airlines | Destinations | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Amazon Air | Cincinnati, Ontario, Seattle/Tacoma | |

| Ameriflight | Poughkeepsie (NY) | |

| DHL Aviation | Rochester (NY) Seasonal: Cincinnati, New York–JFK | |

| FedEx Express | Bridgeport, Indianapolis, Manchester (NH), Memphis, Newark, Portland (ME) Seasonal: Albany, Buffalo, Columbus–Rickenbacker, Harrisburg, Los Angeles, Newburgh, Philadelphia, Raleigh/Durham, Rochester (NY), Washington–Dulles | |

| UPS Airlines | Albany, Boston, Chicago/Rockford, Louisville, Newark, New York–JFK, Ontario, Philadelphia, Providence Seasonal: Buffalo, Dallas/Fort Worth, Des Moines, Harrisburg, Manchester (NH), Portland (OR), Syracuse |

In addition to the regular cargo services described above, Bradley is occasionally visited by Antonov An-124 aircraft operated by Volga-Dnepr Airlines, and Antonov Airlines, transporting heavy cargo, such as Sikorsky helicopters or Pratt & Whitney engines, internationally.

Military operations

- Connecticut Air National Guard

- 103d Airlift Wing (103 AW) "Flying Yankees"

- 118th Airlift Squadron (118 AS): operates the C-130 Hercules. The squadron was previously designated as the 118th Fighter Squadron and operated the Fairchild A-10 Thunderbolt II close air support aircraft from the mid 1970s to 2007. Between 2007 and 2013, the squadron operated the C-21.

- 103d Airlift Wing (103 AW) "Flying Yankees"

- Military air transports that are commonly seen include aircraft such as the KC-135R Stratotanker from bases such as Pease Air Force Base in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and Bangor Air National Guard Base in Bangor, Maine. C-17 Globemaster III aircraft from McGuire Air Force Base and Charleston Air Force Base are a less common but occasional sight.

- Connecticut Army National Guard

- 169th Aviation Regiment, 104th Aviation Regiment, 142nd Aviation Regiment.

- Army Aviation Support Facility and the Army Aviation Readiness Center provides aviation support to Army Operations, MedEvac and Air Assault missions throughout the world. Flying UH60 BlackHawks, CH47 Chinooks, C12 Fixed Wing.

- 169th Aviation Regiment, 104th Aviation Regiment, 142nd Aviation Regiment.

- The Connecticut Wing Civil Air Patrol 103rd Composite Squadron (NER-CT-004) operates out of the airport.[40]

Statistics

Enplaned passenger statistics

| Year | Enplaned passengers | % change | Aircraft movements | % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977[41] | 2,900,000 | n/a | 70,000 | n/a |

| 2000[42] | 3,651,943 | n/a | 169,736 | n/a |

| 2001[43] | 3,416,243 | 165,029 | ||

| 2002[44] | 3,221,081 | 146,592 | ||

| 2003[45] | 3,098,556 | 135,246 | ||

| 2004[46] | 3,326,461 | 144,870 | ||

| 2005[47] | 3,617,453 | 156,090 | ||

| 2006[48] | 3,409,938 | 149,517 | ||

| 2007[49] | 3,231,374 | 141,313 | ||

| 2008[50] | 3,006,362 | 122,837 | ||

| 2009[51] | 2,626,873 | 105,594 | ||

| 2010[52] | 2,640,155 | 103,516 | ||

| 2011[53] | 2,772,315 | 106,951 | ||

| 2012[54] | 2,647,610 | 99,019 | ||

| 2013[55] | 2,681,181 | 95,963 | ||

| 2014[56] | 2,913,380 | 96,477 | ||

| 2015[57] | 2,926,047 | 93,507 | ||

| 2016[58] | 3,025,166 | |||

| 2017[59] | 3,214,976 | |||

| 2018[60] | 3,330,734 | |||

| 2019[1] | 3,379,093 | |||

Top destinations

| Rank | Airport | Enplaned passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orlando, Florida | 352,910 | Frontier, JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit |

| 2 | Atlanta, Georgia | 312,470 | Delta |

| 3 | Charlotte, North Carolina | 273,730 | American |

| 4 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 261,370 | American, United |

| 5 | Baltimore, Maryland | 204,160 | Southwest |

| 6 | Fort Lauderdale, Florida | 180,870 | JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit |

| 7 | Tampa, Florida | 163,530 | JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit |

| 8 | Detroit, Michigan | 150,440 | Delta |

| 9 | Washington–Dulles | 126,030 | United |

| 10 | Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota | 119,180 | Delta |

Airline market share

| Rank | Airline | Total passengers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | American Airlines | 1,607,934 |

| 2 | Southwest Airlines | 1,550,453 |

| 3 | Delta Air Lines | 1,273,263 |

| 4 | JetBlue | 847,899 |

| 5 | United Airlines | 764,287 |

| 6 | Spirit Airlines | 471,277 |

| 7 | Other Airlines | 153,085 |

Future

Airport construction

On July 3, 2012 the Connecticut Department of Transportation released an Environmental Assessment and Environmental Impact Evaluation,[61] detailing a proposal to replace the now-vacant Terminal B with updates and facilities intended to improve access and ease of use for Bradley travelers. The replacement proposal calls for:

- Demolition of the Murphy Terminal and existing International Arrivals Building;

- Construction of a new Terminal B, with two concourses containing a total of 19 gates, two of which could accommodate international widebody aircraft;

- Inclusion of a new Federal Inspection Services facility within the new Terminal;

- Construction of a new Central Utility Plant;

- Relocation of the Terminal B arrival roadway and departure viaduct;

- Realignment of Schoephoester Road; and

- Construction of a new 7-level parking garage and consolidated car rental facility, adding 2,600 public parking spaces and 2,250 rental car spaces.

The proposal calls for a three-phase construction program:

- Demolition of the existing Terminal B, realignment of surface roads and construction of the new garage/rental car facility would occur during the initial phase. The initial phase is estimated to cost between $630 million and $650 million.

- Construction of part of Terminal B and its upper roadway would occur in a second phase, with an estimated completion date of 2018.

- Construction of the final segment of Terminal B and its upper roadway would occur in a third phase, with an estimated completion date of 2028.

Actual completion dates could vary due to funding and demand, but as of May 2018 the project had not left the planning stage.[62]

In 2020 construction began on the ground transportation center, west of the existing garage, with current plans calling for it to host 830 new public parking spaces, a new consolidated rental car facility, and bus stops for regional bus services and a planned shuttle connecting the airport to the Windsor Locks rail station. The projected cost of the facility is $210 million, with construction projected to be complete in 2022.[63]

Ground transportation

Rail

Amtrak and Hartford Line trains serve both the nearby Windsor Locks and Windsor stations.[64] As of 2018, weekday service includes eleven southbound trains and twelve northbound trains at Windsor Locks.[65]

Bus

Connecticut Transit route 34 provides local service connecting Bradley with Windsor and Hartford. Route 30 (the "Bradley Flyer") provides express service to downtown Hartford.[66]

Environment

The Connecticut Air National Guard 103d Airlift Wing leases 144 acres (0.58 km2) in the southwest corner of the airport for their Bradley ANG Base. The base is a designated Superfund site.[61]

Bradley has also been identified as one of the last remaining tracts of grassland in Connecticut suitable for a few endangered species of birds, including the upland sandpiper, the horned lark, and the grasshopper sparrow.[67]

Awards

In 2017, Bradley Airport was named 5th-best airport in the United States by Condé Nast Traveler's Reader's Choice Awards. Bradley scored well with readers in the categories of on-site parking, availability of charging stations and free Wi-Fi, decent restaurant options, and overall relaxed atmosphere.[68]

In 2018, Bradley Airport was named 3rd-best airport in the United States by Condé Nast Traveler's Reader's Choice Awards. Bradley scored well with readers in the categories of flight choices, on-site parking, availability of charging stations and free Wi-Fi, decent restaurant options, and overall relaxed atmosphere.[69]

Accidents and incidents

- On March 4, 1953, a Slick Airways Curtiss-Wright C-46 Commando N4717N on a cargo flight from New York-Idlewild Field crashed. Bradley was experiencing light rain and a low ceiling at the time of the incident. After being cleared to land on Runway 06, the pilot reported problems intercepting the localizer, and continued to circle down to get under the weather. The plane struck trees approximately 1.6 miles (2.6 km) southwest of the airport, killing the crew of two.[70]

- On January 15, 1959, a USAF Douglas DC-4 impacted a wooded hillside in fog without the use of a compass during approach, the pilot survived, the co-pilot and mechanic were killed.[71]

- On July 16, 1971, a Douglas C-47B N74844 of New England Propeller Service crashed on approach. The aircraft was on a ferry flight to Beverly Municipal Airport, Massachusetts when an engine lost power shortly after take-off due to water in the fuel. At the time of the accident, the aircraft was attempting to return to Bradley Airport. All 3 occupants survived.[72]

- On June 4, 1984, a Learjet 23 operated by Air Continental crashed on approach to runway 33 due to asymmetric retraction of the spoilers, 2 crew and 1 passenger were killed.[73]

- On May 3, 1991, a Ryan International (wet-leased by Emery Worldwide) Boeing 727-100QC, N425EX, caught fire during take-off. The take-off was aborted and the three crew members escaped, while the aircraft was destroyed by the fire. The fire was determined to have started in the number 3 engine. It was determined that the 9th stage HP compressor had ruptured.[74]

- On November 12, 1995, American Airlines Flight 1572 crashed while trying to land at Bradley. The plane, a McDonnell Douglas MD-83, was substantially damaged when it impacted trees while on approach to runway 15 at Bradley International Airport. The airplane also impacted an instrument landing system antenna as it landed short of the runway on grassy, even terrain. The cause of the accident was determined to be the pilot's failure to reset the altimeter,[75] however, severe weather may have played a factor. One of the 78 passengers and 5 crew on board were injured.[76]

- On January 21, 1998, a Continental Express ATR-42, N15827, had an emergency during roll on landing. During the landing roll, a fire erupted in the right engine. The airplane was stopped on the runway, the engines were shut down and the occupants evacuated. The fire handles for both engines were pulled and both fire bottles on the right engine discharged. However, the fire in the right engine continued to burn. The airport fire services attended shortly afterward and extinguished the fire.[77]

- On October 2, 2019, a vintage Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress owned by the Collings Foundation carrying three crew and ten passengers crashed into deicing tanks and a shed while attempting an emergency landing and caught fire. Seven deaths and seven injuries were reported, including one person on the ground.[78] Witnesses reported that an engine failed upon takeoff and then the aircraft circled back at low altitude.[79]

See also

- Connecticut World War II Army Airfields

- Hartford–Brainard Airport (HFD)

- FlightSimCon

- Tweed New Haven Airport (HVN)

- Westover Metropolitan Airport (CEF)

- Previously marketed by defunct Skybus Airlines as "Hartford (Chicopee, MA)".

References

- "Calendar Year 2019 Passenger Numbers" (PDF). Bradley International Airport. April 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- FAA Airport Master Record for BDL (Form 5010 PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. May 25, 2017.

- Hanseder, Tony. "Hartford Bradley BDL Airport Overview". Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- "Hartford, CT Bradley International Facts". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "2008 Passenger Boarding Statistics" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- Stoller, Gary. "Bradley Airport's Makeover: Will You 'Love the Journey'?". Connecticut Magazine. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "List of NPIAS Airports" (PDF). FAA.gov. Federal Aviation Administration. October 21, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- Grant, Tina, ed. (1996). International Directory of Company Histories. 12. Detroit, MI: St. James Press. p. 48.

- "Media Kit Fact Sheet". Bradley International Airport. Archived from the original on October 6, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- Marks, Paul (May 28, 2006). "Archaeological Sleuths Hunt For Site of Bradley Airport Namesake's Fatal Crash". Hartford Courant. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

Bradley's fatal accident occurred during a simulated aerial dogfight with Frank Mears, commander of the 64th Pursuit Squadron. The plane Bradley was flying spun out of control as he went into a sharp turn at about 5,000 feet. Stunned witnesses saw the plane spiral slowly into a grove of trees. Soon a column of smoke arose. They theorize that the young pilot blacked out from the gravitational forces felt during such a sharp aerial turn.

- Gershon, Eric (April 2, 2010). "Airlines To Clear Out of Bradley Airport's Murphy Terminal, The Nation's Oldest, By April 15". Hartford Courant. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- Marks, Paul (October 26, 2003). "Bradley: From Field To High-flying Hub". Hartford Courant. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- "People Mover, The Hartford Courant". ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Hartford Courant (1764–1987): A26.

- "Our Collection". Connecticut Trolley Museum. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- "Windsor Locks: Bradley International Airport". Connecticut Explored. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Bradley Airport Master Plan. Bradley International board of directors.

- "Fact Sheet: Federal Inspection Station" (PDF). Bradley International Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- "Rare A380 Flight from Dubai Diverted to Bradley". NBC Connecticut. February 27, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- Gershon, Eric (August 26, 2009). "Embraer Closes Jet Maintenance Center at Bradley Airport Months After Opening". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- Seay, Gregory (March 1, 2011). "Brazil's Embraer reopens at Bradley". Hartford Business Journal. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Smith, Larry (June 21, 2012). "Airport Authority Board Formally Approves Hiring Executive Director". Windsor Locks-East Windsor Patch. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- Kinney, Jim (October 21, 2015). "Aer Lingus announces nonstop flights from Hartford's Bradley Airport to Dublin". Mass Live. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- Seay, Gregory (April 25, 2016). "Why Bradley won its airport tug-of-war for Aer Lingus". Hartford Business. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Gov. Malloy Announces Aer Lingus Commits to Bradley International Airport for at Least Four More Years". State of Connecticut. September 13, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- "International airline ends service at Bradley International". AP News. January 16, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "TAP Portugal Unveils JetBlue Codeshare, Free Stopover Program – Airways Magazine". Airways Magazine. June 13, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- Gosselin, Kenneth R. (January 25, 2017). "Spirit Airlines To Begin Flights From Bradley Airport". Hartford Courant. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- Kinney, Jim (June 16, 2017). "Spirit Airlines has first flight from Bradley to Fort Lauderdale; announces flights to Fort Myers, Tampa". masslive.com. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- Kinney, Jim (November 9, 2017). "Spirit Airlines flights from Bradley to Tampa & Fort Myers begin". masslive.com. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Spirit Airlines to Launch Nonstop Service from Bradley to Fort Myers and Tampa" (Press release). Connecticut Airport Authority. June 15, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Contact CAA". CT Airport Authority. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "Aer Lingus taps $4.5M state subsidy after direct flights miss revenue target". hartfordbusiness.com. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- "AA Flight Schedules". American Airlines. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Departure Results List: Hartford/Springfield (BDL) (11 results) – Delta Air Lines Map". dl.fltmaps.com. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- "Frontier Flights From Hartford". May 9, 2019.

- "Flights to Hartford, Connecticut". www.jetblue.com. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- "Southwest Airlines – Route Map". www.southwest.com. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- "Where We Fly". Spirit Airlines. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Where we fly". united.com. United Airlines. Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- "NER-CT-004 – 103rd Composite Squadron". CT Wing, Civil Air Patrol. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- I-91 Reconstruction from Hartford to Enfield; I-291 Construction from Windsor to Manchester: Environmental Impact Statement. 1981.

- "Primary Airport Enplanement Activity Summary for CY2000" (PDF). FAA. October 19, 2001. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Summary of Enplanement Activity: CY 2001 Compared to CY 2000" (PDF). FAA. 2001. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "CY 2002 Commercial Service Airports in the US with % Boardings Change from 2001" (PDF). FAA. November 6, 2003. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "CY 2003 Commercial Service Airports" (PDF). FAA. 2003. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Primary Airport: Based on Calendar Year 2004 Passenger Enplanements" (PDF). FAA. November 8, 2005. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Calendar Year 2005: Primary and Non-Primary Commercial Service Airports" (PDF). FAA. October 31, 2006. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Calendar Year 2006 Passenger Activity: Commercial Service Airports in US" (PDF). FAA. October 18, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Final Calendar Year 2007 Enplanements and Percent Change from CY06" (PDF). FAA. September 26, 2008. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Commercial Service Airports (Primary and Non-primary): Calendar Year 2008" (PDF). FAA. December 17, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Commercial Service Airports (Primary and Nonprimary): CY09 Passenger Boardings" (PDF). FAA. November 23, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Enplanements at Primary Airports (Rank Order) CY10" (PDF). FAA. October 26, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Calendar Year 2011 Primary Airports" (PDF). FAA. September 27, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Commercial Service Airports, based on Calendar Year 2012 Enplanements" (PDF). FAA. October 30, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Commercial Service Airports based on Calendar Year 2013 Enplanements" (PDF). FAA. January 26, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Calendar Year 2014 Passenger Numbers" (PDF). Bradley International Airport. 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Calendar Year 2015 Passenger Numbers" (PDF). Bradley International Airport. 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Calendar Year 2016 Passenger Numbers" (PDF). Bradley International Airport. August 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Calendar Year 2017 Passenger Numbers" (PDF). Bradley International Airport. February 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "Calendar Year 2018 Passenger Numbers" (PDF). Bradley International Airport. February 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- "Environmental Assessment and Environmental Impact Evaluation, New Terminal B Passenger Facility and Associated Improvements at Bradley International Airport Windsor Locks, Connecticut" (PDF). Connecticut Department of Transportation. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-pol-bradley-master-plan-20180501-story.html

- https://bradleyairport.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Ground-Transportation-Center.pdf

- "Northeast Corridor Boston/Springfield–Washington Timetable" (PDF). Amtrak. June 9, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "Hartford Line Official Inaugural Schedule" (PDF). Hartford Line. June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "Routes & Schedules". Connecticut Transit. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- "Grasslands". Audubon Connecticut. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- "The 10 Best Airports in the U.S." Condé Nast Traveler. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- "The 10 Best Airports in the U.S." Condé Nast Traveler. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- "N4717N Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- Controlled Flight Into Terrain description at the Aviation Safety Network

- "N47844 Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved September 19, 2010.

- Accident description for N101PP at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on April 11, 2019.

- "N425EX Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- "N56AA Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- "Collision with Trees on Final Approach American Airlines Flight 1572, McDonnell Douglas MD-83, N566AA Accident Report Detail". National Transportation Safety Board. November 13, 1996. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- "N15827 Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- "Multiple injuries reported after vintage plane crashes at Bradley International Airport". Hartford Courant. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- "Sources say at least 5 people dead in B-17 crash at Bradley Airport". Fox61.com. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

External links

- Bradley International Airport (official site)

- Connecticut Airport Authority (official site)

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective August 13, 2020

- FAA Terminal Procedures for BDL, effective August 13, 2020

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KBDL

- ASN accident history for BDL

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KBDL

- FAA current BDL delay information