San Diego International Airport

San Diego International Airport (IATA: SAN, ICAO: KSAN, FAA LID: SAN), formerly known as Lindbergh Field, is an international airport 3 mi (4.8 km) northwest of Downtown San Diego, California, United States. It is owned and operated by the San Diego County Regional Airport Authority.[5][6] San Diego International Airport covers 663 acres (268 ha) of land.[5]

San Diego International Airport | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

_Terminal_2_(upper_deck)_-_August_2018.jpg) | |||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||

| Owner/Operator | San Diego County Regional Airport Authority | ||||||||||

| Serves | Greater San Diego | ||||||||||

| Location |

| ||||||||||

| Opened | August 16, 1928 | ||||||||||

| Focus city for | |||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 17 ft / 5 m | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 32°44′01″N 117°11′23″W | ||||||||||

| Website | www.san.org | ||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||

FAA airport diagram as of June 2019 | |||||||||||

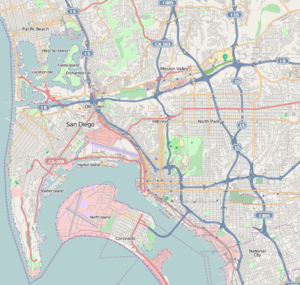

SAN Location within San Diego  SAN SAN (California)  SAN SAN (the United States) | |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Statistics (2019) | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

In 2019, traffic at San Diego International exceeded 25 million passengers, of which more than one million were international passengers.[7] While primarily serving domestic traffic, San Diego has nonstop international flights to destinations in Canada, Germany, Japan, Mexico, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.[8]

San Diego is a focus city for Alaska Airlines and Southwest Airlines. The top five carriers in San Diego as of January 2020 are Southwest Airlines (37.8%), Alaska Airlines (14.3%), Delta Air Lines (12.6%), United Airlines (12%), and American Airlines (11.8%).[9]

San Diego International is the busiest single runway airport in the United States and third-busiest single runway in the world, behind Mumbai Airport and London Gatwick.[10][11] [Note 1] The airport's landing approach is well known for its close proximity to the skyscrapers of Downtown San Diego,[12] and can sometimes prove difficult to pilots for the relatively short usable landing area, steep descent angle over the crest of Banker's Hill, and shifting wind currents just before landing.[13][14] San Diego International operates in controlled airspace served by the Southern California TRACON, which is some of the busiest airspace in the world.[15]

History

The airport is near the site of the Ryan Airlines factory, but it is not the same as Dutch Flats, the Ryan airstrip where Charles Lindbergh flight tested the Spirit of St. Louis before his historic 1927 transatlantic flight. The site of Dutch Flats is on the other side of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, in the Midway neighborhood, near the intersection of Midway and Barnett avenues.[16]

Inspired by Lindbergh's flight and excited to have made his plane, the city of San Diego passed a bond issue in 1928 for the construction of a two-runway municipal airport. Lindbergh encouraged the building of the airport and agreed to lend his name to it.[17] The new airport, dedicated on August 16, 1928, was San Diego Municipal Airport – Lindbergh Field.

The airport was the first federally certified airfield to serve all aircraft types, including seaplanes.[18][19] The original terminal was on the northeast side of the field, on Pacific Highway.[18] The airport was also a testing facility for several early US sailplane designs, notably those by William Hawley Bowlus (superintendent of construction on the Spirit of St. Louis) who also operated the Bowlus Glider School at Lindbergh Field from 1929–1930.[20] The airport was also the site of a national and world record for women's altitude established in 1930 by Ruth Alexander.[21][22] On June 1, 1930, a regular San Diego–Los Angeles airmail route started. The airport gained international airport status in 1934. In April 1937, United States Coast Guard Air Base was commissioned next to the airfield.[23] The Coast Guard's fixed-wing aircraft used Lindbergh Field until the mid-1990s when their fixed-wing aircraft were assigned elsewhere.[24]

A major defense contractor and contributor to World War II heavy bomber production, Consolidated Aircraft, later known as Convair, had their headquarters on the border of Lindbergh Field, and built many of their military aircraft there. Convair used the airport for test and delivery flights from 1935 to 1995.[25]

The US Army Air Corps took over the field in 1942, improving it to handle the heavy bombers being manufactured in the region. Two camps were established at the airport during World War II and were named Camp Consair and Camp Sahara.[26] This transformation, including an 8,750 ft (2,670 m) runway, made the airport "jet-ready" long before jet airliners came into service.[27] The May 1952 C&GS chart shows an 8,700-ft runway 9 and a 4,500-ft runway 13.

Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) established its headquarters in San Diego and started service at Lindbergh Field in 1949. The April 1957 Official Airline Guide shows 42 departures per day: 14 American, 13 United, 6 Western, 6 Bonanza, and 3 PSA (5 PSA on Friday and Sunday). American had a nonstop flight to Dallas and one to El Paso; aside from that, nonstop flights did not reach beyond California and Arizona. Nonstop flights to Chicago started in 1962 and to New York in 1967.

The first scheduled flights using jets at Lindbergh Field were in September 1960: American Airlines Boeing 720s to Phoenix and United Airlines 720s to San Francisco.

The original terminal was on the north side of the airport; the current Terminal 1 opened on the south side of the airport on March 5, 1967. Terminal 2 opened on July 11, 1979. These terminals were designed by Paderewski Dean & Associates.[28] A third terminal, dubbed the Commuter Terminal, opened July 23, 1996. Terminal 2 was expanded by 300,000 square feet (27,871 m2) in 1998, and opened on January 7, 1998. The expanded Terminal 2 and the Commuter Terminal were designed by Gensler and SGPA Architecture and Planning.[29][30] The airport was built and operated by the City of San Diego through the sale of municipal bonds to be repaid by airport users. In 1962 it was transferred to the San Diego Unified Port District by a state law. In 2001 the San Diego County Regional Airport Authority was created, and assumed jurisdiction over the airport in December 2002.[31] The Authority changed the airport's name from Lindbergh Field to San Diego International Airport in 2003, reportedly considering the new name "a better fit for a major commercial airport."[32]

Expansion

San Diego International Airport's expansion and enhancement program for Terminal 2 was dubbed "The Green Build". Additions include 10 gates on the west side of Terminal 2 West, a two-level roadway separating arriving and departing passengers, additional security lanes, and an expanded concession area.[33] It was completed in August 13, 2013 and cost US$900 million.[34] In January 2016, the airport opened a new consolidated rental car facility on the north side of the airport. The US$316 million, 2-million-square-foot (190,000 m2) facility houses 14 rental car companies and is served by shuttle buses to and from the terminals.[35] A new three-story parking structure in front of Terminal 2 was launched in July 2016 and completed in May 2018.[34][36]

The Airport Development Plan (ADP) is the next master-planning phase for San Diego International Airport.[37] In 2006, a county-wide ballot measure to move the airport was defeated. Therefore, the airport will continue in its current location for the foreseeable future. The ADP identifies improvements that will enable the airport to meet demand through 2035, which is approximately when projected passenger activity levels will reach capacity for the airport's single runway. An additional runway is not being considered.

The ADP envisions the replacement of Terminal 1 and related improvements. As a first step in the ADP, several potential concepts were developed. These concepts represented the first step in a comprehensive planning process.

Extensive public outreach was conducted to obtain input from residents and airport stakeholders in the San Diego region. The Airport Authority Board eventually selected a preferred alternative and a detailed environmental analysis is now under way. The environmental review and planning process is expected to conclude in spring 2017.

A new immigration and customs facility at Terminal 2 West began construction in 2017.[38][39] The new facility was completed in June 2018 and is almost five times the size of its predecessor.[40] Prior to its completion, international arrivals were handled at gates 20, 21, and 22 in Terminal 2 East. These arrivals are now handled at gates 47, 48, 49, 50, and 51 in Terminal 2 West. The construction of the new facility was due to the sharp rise of international travel at the airport; international arrivals increased "from 50,000 passengers a year in 1990 to more than 400,000 a year in 2017."[38][40]

San Diego International Airport is proceeding with a redevelopment plan, starting with reconstruction of Terminal 1. This work is scheduled to be completed by 2026. The number of gates will increase from 19 gates in the old Terminal 1 to 30 gates in the new Terminal 1. Other parts of the redevelopment plan include a 7,500-space parking structure, a new dual-level roadway in front of the new Terminal 1, and a new entry road. Further changes are scheduled in later years for Terminal 2, which will increase the total number of gates at San Diego International Airport to 61. Completion of these changes are not expected until 2026.[41]

Relocation proposals

In the jet age there have been concerns about a relatively small airport constrained by terrain serving as the area's primary airport; at one point acting Civil Aeronautics Authority administrator William B. Davis said he doubted any jet airline would use it.[42] In 1950 the city acquired what is today Montgomery Field and much of the land surrounding it through eminent domain in order to build a new airport, but the Korean War brought with it a massive expansion in jet traffic to nearby Naval Air Station Miramar which soon rendered a commercial service airport in the area impractical. The CAA refused to fund any major enhancements to SDIA through the 1950s, and at various times the city proposed NAS North Island, Mission Bay, and Brown Field as replacements. However, cost, conflicts with the Navy, and potential interference with other air traffic stymied all these plans.[42] It was not until 1964 that the FAA would finally agree to an expansion of SDIA, which at this point was over double the capacity of its 1940s era terminals, leading to the construction of today's Terminal 1. Even then, it was only allowed with the assurance of San Diego Mayor Charles Dail that it was only a temporary measure until a replacement could be found.[43] From that time until 2006 various public agencies conducted numerous studies on potential locations for a replacement airport. One was a revisiting of a study done in the 1980s by the City in 1994 when Naval Air Station Miramar closed and was then immediately transferred to the US Marine Corps as Marine Corps Air Station Miramar. Another was by the City of San Diego in 1984 and another that started in 1996 and sat dormant with SANDAG until the airport authority was formed. This study is the first study ever done to look for a new site by a public agency that actually had jurisdiction over the issue, and the first non-site specific comprehensive study of the entire region.

California State Assembly Bill 93 created the San Diego County Regional Airport Authority (SDCRAA) in 2001.[31] At the time the SDCRAA projected that SAN would be constrained by congestion between 2015 and 2022,[44] however, the Great Recession extended the forecast capacity limitations into the 2030s[45] In June 2006, SDCRAA board members selected Marine Corps Air Station Miramar as its preferred site for a replacement airport, despite military objections that the compromises this would require would severely interfere with the readiness and training of aviators stationed at the air station.[46] On November 7, 2006, San Diego County residents rejected an advisory relocation ballot that included a joint use proposal measure over these and related concerns over the potential impact reducing the region's military value would have on the defense focused San Diego economy.[47] Since then no public agency has placed forth a serious proposal to relocate SDIA, and the Airport Authority has stated it has no plans to do so for the foreseeable future[48]

Airport facilities

Terminal facilities

The airport has recently completed a substantial expansion of concessions: 73 new shops and food and beverage locations have opened throughout the terminals.[49] Three airline lounges are located in the airport in Terminal 2: Delta SkyClub, United Club, and a joint Airspace Lounge/American Airlines Admirals Club.[50]

Rental car facilities

Until 2015, major rental cars companies operated out of ground-level facilities across Harbor Drive from the airport, with each company operating its own shuttle. Other companies were located on private property near the airport. In January 2016 the airport opened a consolidated rental car facility on the north side of the airport, housing 14 rental car agencies with capacity for 19. An on-airport shuttle bus service transports passengers to and from the airport. The same shuttle bus also serves passengers from off-site rental car companies, and is intended to carry passengers from a nearby trolley stop as well.[51]

The airport is home to the largest airport USO center in the world.[52]

The airport promotes education about its history,[53] and sponsors an "airport explorers" program.[54]

There are several well-known pieces of art on display at the airport.[55] Inside Terminal 2 is a recreation of The Spirit of St. Louis. "At the Gate", a popular piece with tourists, depicts comical characters patiently waiting for their planes.[56] Terminal 2 also features "The Spirit of Silence," a meditation room designed by public artist Norie Sato.[57]

Terminals

_Terminal_2_(ground_level)_-_August_2018.jpg)

San Diego International Airport has two terminals:

| Terminal | Gates | Airlines | Lounges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terminal 1 East | 11 (1A, 1-10) | Southwest | None |

| Terminal 1 West | 8 (11-18) | Allegiant, Frontier, JetBlue,

Southwest, Spirit, Sun Country |

None |

| Terminal 2 East | 13 (20-32) | Alaska, American | Airspace Lounge/Admirals Club (Joint) |

| Terminal 2 West | 19 (33-51) | Air Canada, British Airways, Delta

Edelweiss, Hawaiian, Japan Airlines, Lufthansa, United, WestJet |

United Club, Delta SkyClub |

- Terminal 1

Terminal 1 has two concourses: East and West, and has 19 gates, numbered 1A and 1–18. Terminal 1 East is currently used by Southwest. Terminal 1 West was previously used by Alaska and Frontier. However, in 2019, Alaska moved to Terminal 2 East. Currently, Terminal 1 West is served by Low Cost Carriers, including Southwest, Spirit, and Frontier.

- Terminal 2

Terminal 2 at SAN has two concourses: East and West, and has 32 gates, numbered 20-51. Terminal 2 East is currently served by American and Alaska, while United, Delta, and all international carriers that fly out of San Diego operate at Terminal 2 West. All international arrivals are handled in the new immigration facilities in Terminal 2 West gates 45-51. Before these facilities were built, international flights arrived at Terminal 2 East gates 20 and 21. At this time, low cost carriers that currently operate out of Terminal 1 West operated out of Terminal 2 West.

- Commuter Terminal (former)

The Commuter Terminal was used for commuter flights to Los Angeles. It had four gates, numbered 1–4. The last flight to use the Commuter Terminal was American Eagle flight #2883, which departed on the evening of June 3, 2015. The last flight of the night from LAX (which would in turn be the first flight on June 4, 2015) docked at Terminal 1. Since then, flights to Los Angeles have departed from Terminal 2. Today, the Commuter Terminal houses the administrative offices of the San Diego County Regional Airport Authority.[58]

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

Cargo

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| Ameriflight | Imperial, Ontario |

| ABX Air | Cincinnati, Phoenix–Sky Harbor |

| FedEx Express | Indianapolis, Los Angeles, Memphis, Oakland, Ontario |

| UPS Airlines | Louisville, Ontario |

General aviation

BBA Aviation's Signature Flight Support (previously known as Landmark Aviation[80]) is the fixed-base operator (FBO) at San Diego International Airport.[81] It services all aircraft ranging from the single-engine Cessna aircraft to the twin-aisle Airbus A340. Generally, it services corporate traffic to the airport. The FBO ramp is located at the northeast end of the airfield.

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | San Francisco, California | 747,000 | Alaska, Southwest, United |

| 2 | Seattle/Tacoma, Washington | 594,000 | Alaska, Delta, Southwest |

| 3 | Phoenix–Sky Harbor, Arizona | 589,000 | American, Southwest |

| 4 | San Jose, California | 582,000 | Alaska, Southwest |

| 5 | Denver, Colorado | 573,000 | Frontier, Southwest, Spirit, United |

| 6 | Sacramento, California | 573,000 | Alaska, Southwest |

| 7 | Las Vegas, Nevada | 570,000 | Allegiant, Delta, Frontier, Southwest, Spirit |

| 8 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 443,000 | American, Spirit |

| 9 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 433,000 | American, Spirit, United |

| 10 | Oakland, California | 381,000 | Southwest |

| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 258,471 | Alaska, Southwest, Sun Country | |

| 2 | 167,648 | British Airways | |

| 3 | 138,841 | Air Canada, WestJet | |

| 4 | 126,756 | Japan Airlines | |

| 5 | 122,676 | Air Canada | |

| 6 | 78,448 | Lufthansa | |

| 7 | 59,639 | Alaska | |

| 8 | 59,188 | WestJet | |

| 9 | 16,894 | Edelweiss | |

Airline market share

| Rank | Carrier | Enplanements | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Southwest | 9,532,000 | 37.8% |

| 2 | Alaska | 3,606,000 | 14.3% |

| 3 | Delta | 3,177,000 | 12.6% |

| 4 | United | 3,026,000 | 12.0% |

| 5 | American | 2,976,000 | 11.8% |

| 6 | Spirit | 630,000 | 2.5% |

| 7 | JetBlue | 530,000 | 2.1% |

| 8 | Frontier | 530,000 | 2.1% |

| 9 | Hawaiian | 303,000 | 1.2% |

| 10 | Air Canada | 252,000 | 1.0% |

| 11 | British Airways | 177,000 | 0.7% |

| 12 | Japan Airlines | 126,000 | 0.5% |

| 13 | Lufthansa | 101,000 | 0.4% |

| 14 | Sun Country | 101,000 | 0.4% |

| 15 | WestJet | 75,700 | 0.3% |

| 16 | Allegiant | 50,400 | 0.2% |

| 17 | Edelweiss | < 25,200 | < 0.1% |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | % Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1949 | 139,327 | |

| 1950 | 193,373 | |

| 1951 | 321,189 | |

| 1952 | 390,427 | |

| 1953 | 402,674 | |

| 1954 | 426,600 | |

| 1955 | 496,641 | |

| 1956 | 582,120 | |

| 1957 | 682,609 | |

| 1958 | 698,543 | |

| 1959 | 786,798 | |

| 1960 | 878,669 | |

| 1961 | 883,288 | |

| 1962 | 951,655 | |

| 1963 | 1,152,065 | |

| 1964 | 1,319,855 | |

| 1965 | 1,632,833 | |

| 1966 | 2,048,034 | |

| 1967 | 2,486,213 | |

| 1968 | 2,958,053 | |

| 1969 | 3,320,576 | |

| 1970 | 3,341,391 | |

| 1971 | 3,464,174 | |

| 1972 | 3,915,395 | |

| 1973 | 4,274,286 | |

| 1974 | 4,410,972 | |

| 1975 | 4,490,668 | |

| 1976 | 4,912,368 | |

| 1977 | 5,447,648 | |

| 1978 | 6,185,583 | |

| 1979 | 6,541,820 | |

| 1980 | 5,213,356 | |

| 1981 | 5,022,152 | |

| 1982 | 5,630,343 | |

| 1983 | 6,547,439 | |

| 1984 | 7,173,272 | |

| 1985 | 7,937,806 | |

| 1986 | 9,084,438 | |

| 1987 | 9,801,030 | |

| 1988 | 10,748,729 | |

| 1989 | 11,111,080 | |

| 1990 | 10,937,026 | |

| 1991 | 11,185,920 | |

| 1992 | 11,759,091 | |

| 1993 | 11,817,706 | |

| 1994 | 12,681,985 | |

| 1995 | 12,908,395 | |

| 1996 | 13,461,361 | |

| 1997 | 13,900,712 | |

| 1998 | 14,340,447 | |

| 1999 | 14,971,261 | |

| 2000 | 15,746,445 | |

| 2001 | 14,942,061 | |

| 2002 | 14,731,518 | |

| 2003 | 15,304,975 | |

| 2004 | 16,517,153 | |

| 2005 | 17,569,355 | |

| 2006 | 17,673,483 | |

| 2007 | 18,326,734 | |

| 2008 | 18,125,633 | |

| 2009 | 16,974,172 | |

| 2010 | 16,889,622 | |

| 2011 | 16,891,690 | |

| 2012 | 17,250,265 | |

| 2013 | 17,710,241 | |

| 2014 | 18,758,751 | |

| 2015 | 20,081,258 | |

| 2016 | 20,725,801 | |

| 2017 | 22,173,493 | |

| 2018 | 24,238,300 | |

| 2019 | 25,216,947 |

Flight operations

Runway configuration and landing

The airport has one runway, designated 9/27 for its magnetic headings of 095 degrees (106 True) and 275 degrees (286 True). The runway is asphalt and concrete, 9,400 feet (2,900 m) x 200 feet (61 m). Each end has a displaced threshold; on runway 27 the first 1,810 feet (550 m) is displaced and on runway 9 the first 1,000 feet (300 m).

Wind is typically from the west and most takeoffs and landings are on runway 27. The approach from the east is steeper than most because trees more than 200 feet above the runway are less than 3200 feet from the east end of the runway (i.e. less than 5000 feet from the displaced threshold.) Contrary to local lore, the parking garage 800 feet east of the end of the runway was built in the 1980s long after previous obstructions were built up east of I-5 and does not affect the approach, nor do any of the nearby downtown skyscrapers.

The final approach into landing has gained notoriety among passengers for the unusual experience of flying low next to such a densely populated area as Downtown San Diego, and has drawn comparisons to Kansas City's Charles B. Wheeler Downtown Airport and Hong Kong's former Kai Tak Airport.[85] Landing from the east offers closeup views of skyscrapers, Petco Park (home of the San Diego Padres), the San Diego Bay, and the San Diego–Coronado Bridge from the left side of the aircraft. On the right, Balboa Park, site of the 1915–1916 Panama-California Exposition, can be seen.

Over time, advances in navigation technology will mitigate many of the concerns people have had over the years with the approach. Improvements included the installation of a Precision Approach Path Indicator (PAPI) in the late 1980’s, development of an RNP approach in 2015, and eventually A Ground Based Augmentation System which will provide precision approaches where they are currently not possible. https://www.airnav.com/airport/KSAN, https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ato/service_units/techops/navservices/gnss/laas/

Reverse operations

Runway 27 (landing east to west), is a localizer and RNP approach with minimums down to 1.5 mi (2.4 km). For Runway 9 the required visibility is 0.5 mi (0.80 km), so when visibility is below 1.5 mi (2.4 km) arriving aircraft must use Runway 9. Terrain east of the airport often imposes weight limits on departing aircraft, so the heaviest ones must take off to the west. While safe, these "head to head" operations slow the flow of aircraft for sequencing and create delays. Due to the way fog can impact the airport being near the bay, this condition can also be driven by different departure minimums at opposite ends of the runway. As an example, visibility for landing may be under 1 1/2 mile for Runway 27 (below arrival minimums) dictating Runway 9 arrivals and less than a mile of visibility for Runway 9 (below departure minimums) dictating the use of Runway 27 for departures.

Terrain east and west of the airport greatly impacts the available runway length. Runway 27 (heading west) has a climb gradient of 353 ft/nmi (58.1 m/km) feet per nautical mile. Taking off to the east requires a 290 ft/nmi (48 m/km) climb rate, this is due to a mathematical reduction in the runway length.

San Diego International Airport does not have standard 1,000 ft (300 m) runway safety areas at the runway ends. An engineered materials arrestor system (EMAS) has been installed at the west end to halt aircraft overruns, but the east end does not have such a system as it would reduce runway length by at least 400 ft (120 m), making departures to the west harder. Instead, the use of declared distances reduces the mathematical length of Runway 9 (west to east operations) by declaring that the easternmost end of Runway 9 is 1,121 ft (342 m) shorter with a net length of 8,280 ft (2,520 m).[86]

Noise curfew

SAN is in a populated area. To appease the concerns of the airport's neighbors regarding noise and possible ensuing lawsuits, a curfew was put in place in 1979. Takeoffs are allowed between 6:30 a.m. and 11:30 p.m. Outside those hours, they are subject to a large fine. Arrivals are permitted 24 hours per day.[87] While several flights have scheduled departure times before 6:30 a.m., these times are pushback times; the first takeoff roll is at 6:30 a.m.

Current status

As of December 2019, San Diego International Airport is served by 18 passenger airlines and five cargo airlines that fly nonstop to over 65 destinations in the United States, Canada, Mexico, United Kingdom, Japan, and most recently, Germany and Switzerland. Several carriers including Alaska and Southwest have increased their flights to and from San Diego. Additional service between SAN and Los Cabos (Mexico), Dallas, Portland, Boston, Washington D.C./Baltimore, Burbank, and Tokyo were added in 2014; however, Burbank has since been discontinued.[88][89][90]

British Airways resumed nonstop service to London Heathrow Airport on June 1, 2011 with a Boeing 777-200ER. The airline had dropped this route in October 2003, after the worldwide downturn in aviation after the September 11 attacks in 2001. The airline had been flying nonstop to London Heathrow; however, the route had originally been flown from Gatwick via Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport on a Boeing 747-400, although it is flown nonstop today. After the September 11 attacks, the route was reduced to six days a week, then five, and then cancelled. In June 2010 the European Union approved the new Atlantic Joint Business Agreement between British Airways, American Airlines, and Iberia Airlines, which dropped many of the provisions of the Bermuda II treaty and its restrictions on airlines flying to Heathrow. Oneworld members now can earn mileage on any American Airlines, British Airways, or Japan Airlines flight.[91] On March 27, 2016, British Airways changed the aircraft on this flight from the 3-class 777-200 to the 4-class 777-300, increasing passenger and cargo capacity, and to provide first class seats. from 2019-2020, British Airways brought back the 747-400 to San Diego, replacing the Boeing 777-300.

Japan Airlines began service to Tokyo–Narita on December 2, 2012, using the Boeing 787 aircraft. This is the airport's first nonstop flight to Asia. The flights used the 787 until its grounding when service was temporarily replaced with a 777-200ER. The last 777 flight was May 31, 2013. On June 1, 2013, 787 service resumed, this time daily. This route is covered under the Pacific Joint Business Agreement between Oneworld partners Japan Airlines and American Airlines.[92][93]

On Thursday, June 9, 2016, Condor Airlines announced thrice-weekly seasonal service from Frankfurt am Main International Airport to San Diego, with Monday flights beginning May 1, 2017, through October 2, 2017, Thursday flights beginning May 4, 2017, through October 5, 2017, and Saturday flights beginning July 8, 2017, through September 2, 2017. Flights were on a Boeing 767-300 aircraft.[94] On June 21, 2016, Edelweiss Air announced twice-weekly seasonal service from Zurich Airport, beginning Monday, June 9, 2017, with the second flight of the week on Fridays. Flights will be on an Airbus A340-300 aircraft.[95] On June 13, 2017, Lufthansa announced five weekly flights from Frankfurt to San Diego beginning in summer 2018, using an A340-300.[96] Soon after this, Condor ended its service. In 2018, the airport saw an increase in passengers, totaling about 24 million, which included 1 million international passengers.[97]

The busiest route by flight count is to Los Angeles with 25 daily round trips on United Express, American Eagle, and Delta Connection. The busiest route by available seats per day is to San Francisco with just over 2,816 seats on 21 daily round trips on United Airlines, Southwest Airlines, and Alaska Airlines.

In January 2008, San Diego International Airport entered the blogosphere with the launch of the first employee blog–the Ambassablog[98]–for a major US airport. Written by front-line employees, the blog features regular posts on airport activities, events, and initiatives; reader comments; and several multimedia and interactive features. It has been presented as a case study in employee blogging to several public agencies at the federal, state, and local levels.

In February 2008, San Diego International Airport was one of the first major airports in the US to adopt a formal sustainability policy, which expresses the airport's commitment to a four-layer approach to sustainability known as EONS. As promulgated by Airports Council International – North America, EONS represents an integrated "quadruple bottom line" of Economic viability, Operational excellence, Natural resource conservation and preservation, and Social responsibility.

In May 2008, California Attorney General Jerry Brown announced an agreement with San Diego International Airport on reducing greenhouse gas emissions associated with the airport's proposed master plan improvements. In announcing the agreement, the Attorney General's office said "San Diego airport will play a key leadership role in helping California meet its aggressive greenhouse gas reduction targets."

San Diego International Airport is testing a new system of airfield lights called Runway Status Lights (RWSL) for the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). It completed the rehabilitation of the north taxiway in 2010. A project that included replacing its airfield lighting and signage with energy-efficient LED lights where possible.

Because of the airport's close proximity to downtown San Diego, FAA regulations do not allow any building within a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) radius of the runway to be taller than 500 feet (150 m).[99]

US Coast Guard operations

_(21581451836).jpg)

Coast Guard Air Station San Diego is located near the southeast corner of the airport. The installation originally supported seaplane operations, with seaplane ramps into San Diego Bay, as well as land-based aircraft and helicopter operations using the airport's runway.

The air station is separated from the rest of the airfield which necessitated moving aircraft across North Harbor Drive, a busy, 6-lane city street, to reach SAN's runway. Stoplights halted vehicle traffic while aircraft crossed North Harbor Drive. This was a common occurrence during the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, when the station had both HH-3F Pelican and HH-60J Jayhawk helicopters and HU-25 Guardian jets assigned.[100] Following 9/11, the gate was closed and the traffic lights removed as the Coast Guard station no longer supports fixed wing operations.

Ground transportation

San Diego International Airport is located on North Harbor Drive, and is accessible from Interstate 5 via the Hawthorn Street northbound exit and the Sassafras Street southbound exit. The airport provides both short-term and long-term parking facilities. Short term parking is located in front of both terminals. Terminal 2 having both a covered parking plaza and an outdoor lot, while Terminal 1 only has an outdoor lot. Long term parking is located on North Harbor Drive to the east of the terminals and is served by shuttle buses.[101]

There are three public transportation options:

- Metropolitan Transit System bus route 992 stops at both Terminals 1 and 2, and connects the airport to Broadway and Kettner in Downtown San Diego, which is within a couple of blocks away from Santa Fe Depot for Amtrak, the San Diego Coaster, and the Green Line of the San Diego Trolley; America Plaza station for the Trolley's Blue Line; and Courthouse station for the Trolley's Orange Line.[102]

- Metropolitan Transit System bus route 923 has stops just outside the airport's boundary directly on North Harbor Drive, and runs between Ocean Beach and downtown.

- The Trolley-to-Terminal shuttle takes passengers from either Terminals 1 or 2 to within one block of the Middletown station. This shuttle also serves the rental car center.[102]

Taxis and ride-share pickups depart from their designated zones at both terminals.[103]

California High-Speed Rail

As of March 3, 2011, the airport was one of a few locations proposed to be the southern terminus of San Diego-Los Angeles branch of the California High-Speed Rail System.[104] Other station proposals included the SDCCU Stadium site and Downtown San Diego.[104] The San Diego portion of the system was to be the last phase of the project, with estimates putting completion sometime in the 2030s and travel time between Los Angeles and San Diego taking 1 hour and 20 minutes.[105]

The high-speed rail option was claimed to be a cheaper alternative to commuter flights to the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area and in-state flights to Central California and the San Francisco Bay Area.[106]

Accidents and incidents

- On April 29, 1929, a Ford Trimotor operated by Maddux Air Lines collided in mid-air with a PW-9D shortly after taking off from Lindbergh Field. The aircraft collided over Downtown San Diego, killing all 5 aboard the Trimotor and the USAAC pilot of PW-9D. According to eyewitness accounts shortly before the collision the Air Corps pilot had been flying extremely close to the larger airliner in an impromptu show for viewers on the ground, when he misjudged the distance between the two aircraft and crashed into it.[107]

- On June 2, 1941, the first British Consolidated LB-30 Liberator II, AL503, on its acceptance flight for delivery from the Consolidated Aircraft Company plant in San Diego, crashed into San Diego Bay[108] when the flight controls froze, killing all five of the civilian crew: Consolidated Aircraft Company's chief test pilot William Wheatley, co-pilot Alan Austen, flight engineer Bruce Kilpatrick Craig, and two chief mechanics, Lewis McCannon and William Reiser. Craig had been commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in the US Army Reserve in 1935 following Infantry ROTC training at the Georgia Institute of Technology, where he earned a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautical engineering. He had applied for a commission in the US Army Air Corps before his death; this was granted posthumously, with the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. On August 25, 1941, the airfield in his hometown of Selma, Alabama was renamed Craig Field, later Craig Air Force Base.[109] Investigation into the cause of the accident caused a two-month delay in deliveries, resulting in the Royal Air Force not receiving Liberator IIs until August 1941.

- On May 10, 1943, the first Consolidated XB-32 Dominator, 41–141, crashed on take-off at Lindbergh Field, likely from failure of the flaps. Although the bomber did not burn when it piled up at end of runway, Consolidated's senior test pilot Dick McMakin was killed. Six others on board were injured.[110] This was one of only two twin-finned B-32s (41–142 was the other); all subsequent planes had a PB4Y-style single tail.

- On November 22, 1944, Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, BuNo 59544, on a pre-delivery test flight out of Lindbergh Field, took off at 12:23 am, lost its left outer wing on climb-out, and crashed in a ravine in an undeveloped area of Loma Portal near the Naval Training Center, less than 2 miles (3.2 km) from the runway. All 6 members of the Consolidated Vultee test crew were killed, including pilot Marvin R. Weller, co-pilot Conrad C. Cappe, flight engineers Frank D. Sands and Clifford P. Bengston, radio operator Robert B. Skala, and Consolidated Vultee field operations employee Ray Estes. A wing panel landed on a home at 3121 Kingsley Street in Loma Portal. The cause was found to be 98 missing bolts; the wing was only attached with four spar bolts. Four employees who either were responsible for installation, or were inspectors who signed off on the undone work, were fired two days later. A San Diego coroner's jury found Consolidated Vultee guilty of "gross negligence" by vote of 11–1 on January 5, 1945, and the Bureau of Aeronautics reduced its contract by one at a cost to firm of US$155,000. Consolidated Vultee paid out US$130,484 to the families of the six dead crew.[111]

- On April 5, 1945, the prototype Ryan XFR-1 Fireball, BuNo 48234, on a test flight over Lindbergh Field, lost skin between the front and rear spars of the right wing, interrupting airflow over the wing and causing it to break apart. Ryan test pilot Dean Lake bailed out as the airframe disintegrated. The wreckage struck a brand new Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, BuNo 59836, just accepted by the US Navy and preparing to depart for the modification center at Litchfield Park, Arizona. The bomber caught fire and the four man Navy crew was forced to evacuate the burning PB4Y, with Aviation Machinist J. H. Randall suffering first, second, and third degree burns and minor lacerations while the rest of the crew was uninjured.[112]

- On April 30, 1945, just before midnight, the first production Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer, BuNo 59359, was being prepared on the ramp at Lindbergh Field for a flight to Naval Air Station Twin Cities in Minneapolis, Minnesota. A mechanic attempted to remove the left battery solenoid, located 14 inches (36 cm) below the cockpit floor, but did so without disconnecting the battery. A ratchet wrench accidentally punctured a hydraulic line 3 inches (7.6 cm) above the battery and the fluid ignited, setting the entire aircraft alight. The mechanic suffered severe burns. Only the number four (outer right) engine was deemed salvageable. The cause was an unqualified mechanic attempting a task that only a qualified electrician should perform.[113]

- On August 5, 1952, Convair B-36D-25-CF Peacemaker, 49-2661, returning from a pre-delivery test after being modified for the San-San project, suffered an uncontrollable engine fire in the right wing while attempting to land at Lindbergh Field. The #4 and #5 engines fell off the aircraft as the Convair test crew steered the crippled bomber towards the ocean. Seven of the eight crew onboard bailed out, with Pilot David H. Franks heroically electing to stay with the aircraft to prevent it turning back towards the heavily populated coast,[114] but flight engineer W.W. Hoffman drowned before he could be rescued. A USAF accident investigation was inconclusive, with a failure in the #5 engine's alternator, supercharger, fuel or exhaust systems suggested as possible causes.[115]

- On July 15, 1953, the prototype Convair XP5Y-1 Tradewind seaplane, BuNo 121455, on a test flight off Point Loma after taking off from the water next to Lindbergh Field, fractured an elevator torque tube rendering the aircraft uncontrollable. All 9 onboard bailed out safely and were rescued.[116]

- On November 4, 1954, an experimental Convair YF2Y Sea Dart seaplane, BuNo 135762, on a demonstration flight for Navy officials over San Diego Bay after taking off from the water next to Lindbergh Field, disintegrated in mid-air after its pilot inadvertently exceeded the airframe's structural limits. Convair test pilot Charles E. Richbourg was pulled from the water but did not survive.[117]

- On September 25, 1978, a Boeing 727-200 operating flight PSA Flight 182 on the Sacramento–Los Angeles–San Diego route collided in mid-air with a Cessna 172 while attempting to land at San Diego Airport. The two aircraft collided over San Diego's North Park neighborhood, killing all 135 people on Flight 182, the two people in the Cessna, and seven people on the ground. An NTSB accident investigation found the probable cause of the accident was the PSA flight crew's failure to inform the tower they had lost sight of the Cessna, in contradiction to Air Traffic Control instructions to "keep visual separation" from the smaller aircraft. Other factors named were errors on the part of ATC, including the use of pilot maintained visual separation when ATC monitored radar clearances were available, and an unexpected turn by the Cessna that put it directly in the path of the 727.[118]

Recognition and awards

- Airports Council International (ACI) ranked San Diego International Airport the No. 4 best airport in North America in 2007. ACI also ranked SAN the No. 2 best airport in the world with 15–25 million passengers in 2007.[119] ACI also ranked SAN the No. 3 best airport in the world with 15–25 million passengers in 2008.

- San Diego International Airport also earned LEED Gold certification for The Green Build's Dual-Level Roadway and USO Building.[120]

Endangered species habitat

A portion of the southeast infield at San Diego International Airport is set aside as a nesting site for the endangered California least tern. The least tern nests on three ovals from March through September. The birds lay their eggs in the sand and gravel surface at the southwest end of the airfield. The San Diego Zoological Society monitors the birds from May through September. The terns nest on the airfield because they do not have to compete with beach goers and the airport fence keeps dogs and other animals out, while the airplane activity helps keep predatory hawks away from the nests. Approximately 135 nests were established there in 2007.[121]

Notes

- 1.^ In addition, both London Gatwick and Mumbai International physically possess two runways, of which only one can be used at a time because of aircraft separation requirements. San Diego International's "true" single runway places additional constraints on operations as performing any repairs on it effectively requires the closure of the airport.[122]

References

- "Airport History". San Diego County Airport Authority. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "Alaska Airlines is in a Newark State of Mind". Splash.alaskasworld.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- Hirsh, Lou (January 25, 2016). "San Diego International Airport Tops 20 Million Passengers for 2015". San Diego Business Journal. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- "Air Traffic Reports". San Diego County Regional Airport Authority. 2017. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- FAA Airport Master Record for SAN (Form 5010 PDF). US Federal Aviation Administration. Effective October 25, 2007.

- "About the Airport Authority". San Diego County Regional Airport Authority. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006.

- Concepcion, Mariel (February 25, 2020). "San Diego International Airport Breaks Passenger Traffic Record". San Diego Business Journal. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Ken Harrison (May 8, 2017). "Two more nonstop flights to Europe from San Diego". San Diego Reader. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- "San Diego International Airport official website: Airport History". Archived from the original on September 2, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- Summers, Dave (May 30, 2015). "FAA Takes Steps to Change Rules Regarding Mental and Emotional Health of Pilots". KNSD. San Diego. Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

Ziff Davis, Inc. (September 5, 2006). PC Mag. Ziff Davis, Inc. p. 24. ISSN 0888-8507. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

Developing an Airport Performance-measurement System. Transportation Research Board. January 1, 2010. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-309-15477-2. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

Halverstadt, Lisa (September 23, 2014). "For San Diego Businesses, the Sky Is What's Limiting". Voice of San Diego. Retrieved June 23, 2015. - Matthew Garcia (May 15, 2017). "Mumbai Now the Busiest Single-Runway Airport in the World". Airline Geeks. Archived from the original on May 29, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

Mumbai [...] now handles 837 flights a day, a significant amount [more] than the previous title holder, London Gatwick, which handles 757 flights a day.

- Lori Weisberg (August 3, 2011). "How safe is San Diego airport?". Retrieved June 21, 2019.

Anyone who’s ever glanced skyward as a jetliner is making its final approach into Lindbergh Field would swear that it could easily scrape one of the high-rises in its path. As scary as the impending landing seems, San Diego International Airport is in fact the seventh safest airfield in the U.S., according to Travel + Leisure magazine.

- Sean Breslin (March 21, 2017). "The 10 Most Challenging U.S. Airports, According to Honeywell". Archived from the original on June 22, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

Weather in San Diego is known for being ideal much of the year, but there are other factors that make arrivals and departures to this airport among the toughest in the nation. According to Honeywell, pilots must make a steep approach into the airport, and strong tailwinds can also be present.

- RALPH FRAMMOLINO and GEORGE RAMOS (April 26, 1988). "S.D. Airport Rated 5th on Danger List: Pilots Call LAX Most Dangerous in Nation". Archived from the original on June 22, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

The mountains to the east force pilots to make a steep landing on a relatively short runway, said Dick Russell, a United Airlines pilot and area safety coordinator for the Air Line Pilots Assn. (ALPA) chapter in Los Angeles. The runway measures 9,400 feet, but angling in over the man-made and natural obstacles effectively shortens that by 1,800 feet, Russell said.

- "Southern California TRACON (SCT)". US Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on May 29, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

Southern California TRACON (SCT) serves most airports in Southern California and guides about 2.2 million planes over roughly 9,000 square miles in a year, making our facility one of the busiest in the world.

- "Port of San Diego map". February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "CharlesLindbergh.com" (PDF). February 15, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- AECOM (May 2018). Midway-Pacific Highway Community Plan Update (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego. pp. 2–13. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Katrina Pescador; Alan Renga; Pamela Gay (2012). San Diego International Airport Lindbergh Field. Images of Aviation. San Diego Air & Space Museum. Arcadia Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7385-8908-4. LCCN 2011936592.

- Michelson, Alan (205). "San Diego County Regional Airport Authority, San Diego Municipal Airport Lindbergh Field, Bowlus, William Hawley, Glider School, San Diego, CA". Pacific Coast Architecture Database. University of Washington. Archived from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Hannah S. Cohen; Gloria G. Harris (November 21, 2016). Remarkable Women of San Diego: Pioneers, Visionaries and Innovators. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-1-62585-726-2.

- "Ruth Alexander Killed in San Diego Air Crash". Evening Tribune. San Diego. September 18, 1930. Archived from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "Coast Guard Activities San Diego" (PDF). Department of Defense. December 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Schnaifer, Jeff (August 26, 1995). "Sportswriter on Deep-Sea Outing Reported Missing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

Coast Guard Sector San Diego (2010). The Coast Guard in San Diego. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7385-8014-2. - "San Diego Air and Space Museum". San Diego and Space Museum. September 15, 2013. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- "San Diego Municipal Airport". California Military Museum System. California Military Department. March 25, 2016. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

Two cantonment areas, Camps Consair and Sahara, were constructed to house troops attending factory schools and other Army activities located at the airport.

- "Official site". San.org. February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "Paderewski, CJ – Modern San Diego Dot Com". Modernsandiego.com. July 23, 1908. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "Lorraine Francis, AIA, LEED AP". Cadiz Design Studio. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "Special Projects". SGPA. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- Wayne. "California Assembly Bill 93". Leginfo.ca.gov. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- Kinsee Morlan (August 15, 2018). "The Airport Is Sticking by Charles Lindbergh". Voice of San Diego. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- "The Green Build at San Diego County Regional Airport Authority". Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- Hirsh, Lou (July 28, 2016). "Construction Starting on $127.8 Million Airport Parking Plaza". San Diego Business Journal. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- "Airport Plans Jan. 20 Opening for New Rental Car Center By SDBJ Staff". San Diego Business Journal. January 13, 2016. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- Weisberg, Lori (May 17, 2018). "San Diego airport adds more parking spaces". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- "San Diego International Airport > Airport Projects > Airport Development Plan". san.org. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- Showley, Roger. "International travel speeds up $229M terminal customs expansion in San Diego". Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- "Federal Inspection Station". www.san.org. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Lane, Kerri. "International Arrivals facility to open at San Diego International Airport". CBS News 8. Archived from the original on May 29, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- "What's in the San Diego International Airport's $3 billion redevelopment plan?". July 11, 2018. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- "City of the Dream, 1940-1970". Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "SDIA Airport Development Plan Project Historic Resources Study - July 2018a" (pdf). 2018.

- "Airport Master Plan". San Diego International Airport. San Diego County Regional Airport Authority. December 11, 2005. Archived from the original on December 11, 2005. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "Stuck on the Waterfront, the Airport's Sky Isn't Falling as Once Feared". The Voice of San Diego. July 8, 2015. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- SDCRAA Endorses Miramar For New Airport Site, Despite Military Protest (San Diego Tribune: June 5, 2006)

- "Airport Measure Shot Down". Voiceofsandiego.org. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "Airport Usage Is Up — But Demand to Move and Expand It Is Way Down". The Voice of San Diego. March 22, 2018. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- "San Diego International Airport > Shop Dine Relax". San.org. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- "San Diego Airport- Airspace Lounge page". San.org. February 23, 2015. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- Hirsh, Lou (January 12, 2015). "Airport Plans Jan. 20 Opening for New Rental Car Center". San Diego Business Journal. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Lee, Joseph Andrew (July 27, 2013). "San Diego Opens Largest USO Airport Center in the World". USO News. United Service Organization. Archived from the original on March 13, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

Peterson, Karla (February 2, 2015). "Mr. USO's big welcome mat". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

Sutton, Lea (September 26, 2013). "Largest USO Airport Center in World Opens at Lindbergh Field". KNSD. San Diego. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

Steele, Jeanette (June 25, 2013). "USO: New center raises profile". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved April 28, 2015. - "Aviation Education at San Diego International Airport". San.org. Archived from the original on August 11, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- "Airport Explorers at San Diego International Airport". Airportexplorers.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- "Welcome to San Diego International Airport". Art.san.org. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- "At the Gate at San Diego International Airport". Art.san.org. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- "Travelers at San Diego's downtown airport now have a new place to relax — Lindbergh Field's first ever meditation room". San Diego Union Tribune. June 20, 2014.

- "Commuter Terminal Ceases Flight Operations at Lindbergh". Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- "Flight Schedules". Air Canada. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- "Air Transat - Flights to San Diego". Air Transat. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- "Alaska Airlines 4Q20 Network expansion as of 16JUL20". Routesonline. July 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- https://www.united.com/web/en-US/apps/travel/timetable/default.aspx

- "Flight Timetable". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Allegiant Airlines to launch summertime flights between Eugene and San Diego". Archived from the original on March 7, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- "Flight schedules and notifications". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- https://www.routesonline.com/news/38/airlineroute/292807/american-airlines-los-angeles-domestic-network-adjustment-from-oct-2020/?highlight=American%20Airlines

- "Timetables". British Airways. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on January 14, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Frontier". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- "Destinations". Archived from the original on January 29, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Japan Airlines Timetables". Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "JetBlue Airlines Timetable". Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Timetable - Lufthansa Canada". Lufthansa. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- "Check Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Where We Fly". Spirit Airlines. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Route Map & Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "Flight schedules". Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- "BBA Aviation completes the acquisition of Landmark Aviation". www.signatureflight.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- "San Diego International Airport > Travel Info". www.san.org. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- "San Diego, CA: San Diego International (SAN)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "U.S. International Air Passenger and Freight Statistics Report". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. 2017. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- "San Diego International Airport > News > Air Traffic Reports". San.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- Moser, Robert Harlan (2002). Past Imperfect: A Personal History of an Adventuresome Lifetime in and Around Medicine. iUniverse. p. 242. ISBN 0595263887.

Before the new monster island skyport (Chek Lap Kok) was created, Kai Tak was jammed into an unbelievably small area, seemingly in the midst of downtown Kowloon. (The approach and take off will always rank close to the top of "One's Greatest Air Travel Adventures." It reminded me of the old Kansas City and current San Diego flight paths, but even scarier; you zoomed in at penthouse level, eye-balling surrounding, not-too-tall office buildings.)

- "KSAN – San Diego International Airport". AirNav. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". san.org. The San Diego County Regional Airport Authority. Archived from the original on November 13, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- "San Diego International Airport > Flights > Airlines". Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- "San Diego International Airport > Flights > Airlines". Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- "San Diego International Airport > Flights > Non-Stop Destinations". Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- "British Airways to try S.D.-to-London flight for a third time Page 1 of 2". San Diego Union Tribune. October 6, 2010. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- Mutzabaugh, Ben (February 15, 2012). "Japan Airlines will use Dreamliner to fly from San Diego". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- Weisburg, Lori (June 13, 2012). "Nonstop flights to Japan start Dec. 2". San Diego Union Tribune. Archived from the original on June 16, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- "Condor announces new seasonal nonstop flights between San Diego and Germany". Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- "Edelweiss to begin nonstop seasonal service between Zurich and San Diego". Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- "Lufthansa Plans New Destinations From Frankfurt, Munich In 2018". Archived from the original on June 18, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- "San Diego's Lindbergh Field breaks passenger record fifth year in a row". KGTV. San Diego. City News Service. February 22, 2019. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "Ambassablog". Ambassablog. April 16, 2012. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "AC 150/5190-4A - A Model Zoning Ordinance to Limit Height of Objects Around Airports". US Federal Aviation Administration. December 14, 1987. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- Coast Guard Sector San Diego (2010). The Coast Guard in San Diego. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-8014-2.

- "Parking". San Diego International Airport. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Public Transportation". San Diego International Airport. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- "To and From". San Diego International Airport. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Preliminary Alternatives Analysis Report Los Angeles to San Diego via the Inland Empire Section" (PDF). March 3, 2011. pp. 59, 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

San Diego Station Alternative:This alternative has three station options. One of these will be selected as the preferred station alternative to be carried forward for further study: Qualcomm Stadium Terminus Station Option, San Diego International Airport Station Option, Downtown San Diego Station Option.

- Tony Mendoza (May 4, 2017). "Connecting and Transforming California" (PDF). Association of Commuter Transportation Southern California Chapter. pp. 9, 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

Los Angeles to San Diego in 1 hour 20 minutes

- Megan Burke; Maureen Cavanaugh (March 30, 2010). "How Long Will It Take To Bring High Speed Rail to California?". KPBS. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

But we've taken a look at a couple of scenarios comparing what a high-speed train ticket would cost compared to airfare over the same distance. We've looked at costing about 50% of what an airplane ticket would cost or 83% of what an airplane ticket would cost. In each one of those cases, we see the system as being able to make revenue. Now unique to California is that our system will not use any government operating subsidies so it will have to support itself on the ticket fares alone. And so that'll be part of the decision that goes into what we'll charge for a trip.

- "Aviation Safety Network". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- "AL503". RAF Liberator Squadrons. January 1, 1970. Archived from the original on February 24, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- "The Memorialization of Lackland Streets" (PDF). Lackland Air Force Base. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 15, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Johnsen, Frederick A., "Dominator: Last and Unluckiest of the Hemisphere Bombers", Wings, Granada Hills, California, February 1974, Volume 4, Number 1, p. 10.

- Veronico, Nicholas A., " 'Failure at the Factory", Air Enthusiast, Stamford, Lincs, UK, Number 124, July–August 2006, pp.31–33.

- Veronico, Nicholas A., " 'Failure at the Factory", Air Enthusiast, Stamford, Lincs, UK, Number 124, July–August 2006, p. 33.

- Veronico, Nicholas A., " 'Failure at the Factory", Air Enthusiast, Stamford, Lincs, UK, Number 124, July–August 2006, p. 35.

- Associated Press, "Civilian Pilot Hailed as B-36 Crash Hero: Bomber Turned Away From Crowded Beach Area Before Explosion Near San Diego", Los Angeles Times, August 7, 1952.

- "Report of Special Investigation of Major Aircraft Accident Involving B-36D, SN 49-2661, at San Diego Bay, San Diego, California, on 5 August 1952", Office of The Inspector General USAF, Norton Air Force Base, San Bernardino, California, 19 September 1952.

- Macha, G. Pat. Historic Aircraft Wrecks of San Diego County. The History Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-46711-836-1.

- Jackson, Robert (1986). Combat Aircraft Prototypes Since 1945. Arco/Prentice Hall Press. p. 161. ISBN 0-671-61953-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aircraft Accident Report 79-5 (AAR-79-5) (PDF), National Transportation Safety Board, hosted by PSA history.org, April 20, 1979, archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012, retrieved December 12, 2007.

- "San Diego-Lindbergh Field Ranked No. 4 Best Airport in North America" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "San Diego Now Home to World's First LEED Platinum Certified Commercial Airport Terminal" (Press release). San Diego International Airport. April 9, 2014. Archived from the original on June 30, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- Davis, Rob (August 31, 2007). "Wildlife Agency Gets Pushback in Downgrading Endangered Bird". Voice of San Diego. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- Steele, Jeanette (November 20, 2017). "San Diego Int'l Airport will dig up the runway every night for a year". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on August 11, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

External links

![]()

- Official website

- Flight planner section of the airport's website

- The Ambassablog – official Airport Authority employee blog

- Airliners.net – search for San Diego under Photo Search and see the colorful past of San Diego airport through the years

- San Diego Airport parking

- IMDB movie: Billy Wilder's The Spirit of St. Louis, starring James Stewart, 1957

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective August 13, 2020

- FAA Terminal Procedures for SAN, effective August 13, 2020

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KSAN

- ASN accident history for SAN

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KSAN

- FAA current SAN delay information