Poverty

Poverty is not having enough material possessions or income for a person's needs.[2] Poverty may include social, economic, and political elements.

Absolute poverty is the complete lack of the means necessary to meet basic personal needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter.[3] The threshold at which absolute poverty is defined is always about the same, independent of the person's permanent location or era.

On the other hand, relative poverty occurs when a person cannot meet a minimum level of living standards, compared to others in the same time and place. Therefore, the threshold at which relative poverty is defined varies from one country to another, or from one society to another.[4] For example, a person who cannot afford housing better than a small tent in an open field would be said to live in relative poverty if almost everyone else in that area lives in modern brick homes, but not if everyone else also lives in small tents in open fields (for example, in a nomadic tribe).

Governments and non-governmental organizations try to reduce poverty. Providing basic needs to people who are unable to earn a sufficient income can be hampered by constraints on government's ability to deliver services, such as corruption, tax avoidance, debt and loan conditionalities and by the brain drain of health care and educational professionals. Strategies of increasing income to make basic needs more affordable typically include welfare, economic freedoms and providing financial services.[5]

Definitions and etymology

The word poverty comes from the old (Norman) French word poverté (Modern French: pauvreté), from Latin paupertās from pauper (poor).[6]

There are several definitions of poverty depending on the context of the situation it is placed in, and the views of the person giving the definition.

United Nations: Fundamentally, poverty is the inability of having choices and opportunities, a violation of human dignity. It means lack of basic capacity to participate effectively in society. It means not having enough to feed and clothe a family, not having a school or clinic to go to, not having the land on which to grow one's food or a job to earn one's living, not having access to credit. It means insecurity, powerlessness and exclusion of individuals, households and communities. It means susceptibility to violence, and it often implies living in marginal or fragile environments, without access to clean water or sanitation.[7]

World Bank: Poverty is pronounced deprivation in well-being, and comprises many dimensions. It includes low incomes and the inability to acquire the basic goods and services necessary for survival with dignity. Poverty also encompasses low levels of health and education, poor access to clean water and sanitation, inadequate physical security, lack of voice, and insufficient capacity and opportunity to better one's life.[8]

Classifications of poverty

Absolute poverty

Absolute poverty refers to a set standard which is consistent over time and between countries. First introduced in 1990, the dollar a day poverty line measured absolute poverty by the standards of the world's poorest countries. The World Bank defined the new international poverty line as $1.25 a day in 2008 for 2005 (equivalent to $1.00 a day in 1996 US prices).[9][10] In October 2015, they reset it to $1.90 a day.[11]

Absolute poverty, extreme poverty, or abject poverty is "a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information. It depends not only on income but also on access to services."[12] The term 'absolute poverty', when used in this fashion, is usually synonymous with 'extreme poverty': Robert McNamara, the former president of the World Bank, described absolute or extreme poverty as, "a condition so limited by malnutrition, illiteracy, disease, squalid surroundings, high infant mortality, and low life expectancy as to be beneath any reasonable definition of human decency."[13][notes 1][14] Australia is one of the world's wealthier nations. In his article published in Australian Policy Online, Robert Tanton notes that, "While this amount is appropriate for third world countries, in Australia, the amount required to meet these basic needs will naturally be much higher because prices of these basic necessities are higher."

However, as the amount of wealth required for survival is not the same in all places and time periods, particularly in highly developed countries where few people would fall below the World Bank Group's poverty lines, countries often develop their own national poverty lines.

An absolute poverty line was calculated in Australia for the Henderson poverty inquiry in 1973. It was $62.70 a week, which was the disposable income required to support the basic needs of a family of two adults and two dependent children at the time. This poverty line has been updated regularly by the Melbourne Institute according to increases in average incomes; for a single employed person it was $391.85 per week (including housing costs) in March 2009.[15] In Australia the OECD poverty would equate to a "disposable income of less than $358 per week for a single adult (higher for larger households to take account of their greater costs).[16] in 2015 Australia implemented the Individual Deprivation Measure which address gender disparities in poverty.[17]

For a few years starting 1990, the World Bank anchored absolute poverty line as $1 per day. This was revised in 1993, and through 2005, absolute poverty was $1.08 a day for all countries on a purchasing power parity basis, after adjusting for inflation to the 1993 U.S. dollar. In 2005, after extensive studies of cost of living across the world, The World Bank raised the measure for global poverty line to reflect the observed higher cost of living.[18] In 2015, the World Bank defines extreme poverty as living on less than US$1.90 (PPP) per day, and moderate poverty as less than $2 or $5 a day (but note that a person or family with access to subsistence resources, e.g., subsistence farmers, may have a low cash income without a correspondingly low standard of living – they are not living "on" their cash income but using it as a top up). It estimated that "in 2001, 1.1 billion people had consumption levels below $1 a day and 2.7 billion lived on less than $2 a day."[19] A 'dollar a day', in nations that do not use the U.S. dollar as currency, does not translate to living a day on the equivalent amount of local currency as determined by the exchange rate.[20] Rather, it is determined by the purchasing power parity rate, which would look at how much local currency is needed to buy the same things that a dollar could buy in the United States.[20] Usually, this would translate to less local currency than the exchange rate in poorer countries as the United States is a relatively more expensive country.[20]

The poverty line threshold of $1.90 per day, as set by the World Bank, is controversial. Each nation has its own threshold for absolute poverty line; in the United States, for example, the absolute poverty line was US$15.15 per day in 2010 (US$22,000 per year for a family of four),[21] while in India it was US$1.0 per day[22] and in China the absolute poverty line was US$0.55 per day, each on PPP basis in 2010.[23] These different poverty lines make data comparison between each nation's official reports qualitatively difficult. Some scholars argue that the World Bank method sets the bar too high, others argue it is too low. Still others suggest that poverty line misleads as it measures everyone below the poverty line the same, when in reality someone living on $1.20 per day is in a different state of poverty than someone living on $0.20 per day. In other words, the depth and intensity of poverty varies across the world and in any regional populations, and $1.25 per day poverty line and head counts are inadequate measures.[22][24][25]

Relative poverty

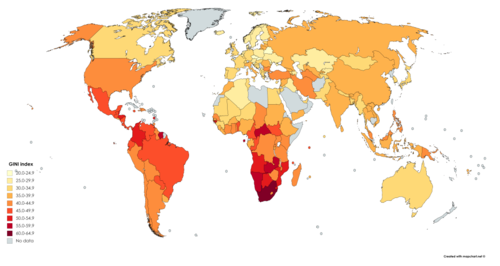

Relative poverty views poverty as socially defined and dependent on social context, hence relative poverty is a measure of income inequality. Usually, relative poverty is measured as the percentage of the population with income less than some fixed proportion of median income. There are several other different income inequality metrics, for example, the Gini coefficient or the Theil Index.

Relative poverty is the "most useful measure for ascertaining poverty rates in wealthy developed nations".[26][27][28][29][30] Relative poverty measure is used by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Canadian poverty researchers.[26][27][28][29][30] In the European Union, the "relative poverty measure is the most prominent and most-quoted of the EU social inclusion indicators".[31]

"Relative poverty reflects better the cost of social inclusion and equality of opportunity in a specific time and space."[32]

"Once economic development has progressed beyond a certain minimum level, the rub of the poverty problem – from the point of view of both the poor individual and of the societies in which they live – is not so much the effects of poverty in any absolute form but the effects of the contrast, daily perceived, between the lives of the poor and the lives of those around them. For practical purposes, the problem of poverty in the industrialized nations today is a problem of relative poverty (page 9)."[32][33]

In 1776 Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations argued that poverty is the inability to afford, "not only the commodities which are indispensably necessary for the support of life but whatever the custom of the country renders it indecent for creditable people, even of the lowest order, to be without".[34][35]

In 1958 J. K. Galbraith argued that "People are poverty stricken when their income, even if adequate for survival, falls markedly behind that of their community."[35][36]

In 1964 in a joint committee economic President's report in the United States, Republicans endorsed the concept of relative poverty. "No objective definition of poverty exists... The definition varies from place to place and time to time. In America as our standard of living rises, so does our idea of what is substandard."[35][37]

In 1965 Rose Friedman argued for the use of relative poverty claiming that the definition of poverty changes with general living standards. Those labeled as poor in 1995 would have had "a higher standard of living than many labeled not poor" in 1965.[35][38]

In 1979, British sociologist, Peter Townsend published his famous definition, "individuals ... can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the types of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and amenities which are customary, or are at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies to which they belong (page 31)".[39]

Brian Nolan and Christopher T. Whelan of the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) in Ireland explained that "Poverty has to be seen in terms of the standard of living of the society in question."[40]

Relative poverty measures are used as official poverty rates by the European Union, UNICEF, and the OECD. The main poverty line used in the OECD and the European Union is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 60% of the median household income.[41]

Many wealthy nations have seen an increase in relative poverty rates ever since the Great Recession, in particular among children from impoverished families who often reside in substandard housing and find educational opportunities out of reach.[42]

Poverty rate is a calculation of the percentage of people whose family household income falls below the Poverty Line. The United States federal government typically regulates this line, and typically the cost of the line is set to three times the cost an adequate meal. This line is subject to change based on the level of price changes and size of the family. According to census, poverty rate helped determine that around 14.8% of U.S population had household incomes that was below the poverty line for their family size in 2014.[43]

Secondary poverty

Secondary poverty refers to those that earn enough income to not be impoverished, but who spend their income on unnecessary pleasures, such as alcoholic beverages, thus placing them below it in practice.[44]

In 18th- and 19th-century Great Britain, the practice of temperance among Methodists, as well as their rejection of gambling, allowed them to eliminate secondary poverty and accumulate capital.[45]

Other aspects

Economic aspects of poverty focus on material needs, typically including the necessities of daily living, such as food, clothing, shelter, or safe drinking water. Poverty in this sense may be understood as a condition in which a person or community is lacking in the basic needs for a minimum standard of well-being and life, particularly as a result of a persistent lack of income. The increase in poverty runs parallel sides with unemployment, hunger, and higher crime rate.

Analysis of social aspects of poverty links conditions of scarcity to aspects of the distribution of resources and power in a society and recognizes that poverty may be a function of the diminished "capability" of people to live the kinds of lives they value. The social aspects of poverty may include lack of access to information, education, health care, social capital or political power.[46][47]

Poverty levels are snapshot pictures in time that omits the transitional dynamics between levels. Mobility statistics supply additional information about the fraction who leave the poverty level. For example, one study finds that in a sixteen-year period (1975 to 1991 in the U.S.) only 5% of those in the lower fifth of the income level were still at that level, while 95% transitioned to a higher income category.[48] Poverty levels can remain the same while those who rise out of poverty are replaced by others. The transient poor and chronic poor differ in each society. In a nine-year period ending in 2005 for the U.S., 50% of the poorest quintile transitioned to a higher quintile.[49]

Poverty may also be understood as an aspect of unequal social status and inequitable social relationships, experienced as social exclusion, dependency, and diminished capacity to participate, or to develop meaningful connections with other people in society.[50][51][39] Such social exclusion can be minimized through strengthened connections with the mainstream, such as through the provision of relational care to those who are experiencing poverty.

The World Bank's "Voices of the Poor," based on research with over 20,000 poor people in 23 countries, identifies a range of factors which poor people identify as part of poverty. These include:

- Abuse by those in power

- Dis-empowering institutions

- Excluded locations

- Gender relationships

- Lack of security

- Limited capabilities

- Physical limitations

- Precarious livelihoods

- Problems in social relationships

- Weak community organizations

- Discrimination

David Moore, in his book The World Bank, argues that some analysis of poverty reflect pejorative, sometimes racial, stereotypes of impoverished people as powerless victims and passive recipients of aid programs.[52]

Ultra-poverty, a term apparently coined by Michael Lipton,[53] connotes being amongst poorest of the poor in low-income countries. Lipton defined ultra-poverty as receiving less than 80 percent of minimum caloric intake whilst spending more than 80% of income on food. Alternatively a 2007 report issued by International Food Policy Research Institute defined ultra-poverty as living on less than 54 cents per day.[54]

Asset poverty is an economic and social condition that is more persistent and prevalent than income poverty.[55] It can be defined as a household's inability to access wealth resources that are enough to provide for basic needs for a period of three months. Basic needs refer to the minimum standards for consumption and acceptable needs.Wealth resources consist of home ownership, other real estate (second home, rented properties, etc.), net value of farm and business assets, stocks, checking and savings accounts, and other savings (money in savings bonds, life insurance policy cash values, etc.). Wealth is measured in three forms: net worth, net worth minus home equity, and liquid assets. Net worth consists of all the aspects mentioned above. Net worth minus home equity is the same except it does not include home ownership in asset calculations. Liquid assets are resources that are readily available such as cash, checking and savings accounts, stocks, and other sources of savings. There are two types of assets: tangible and intangible. Tangible assets most closely resemble liquid assets in that they include stocks, bonds, property, natural resources, and hard assets not in the form of real estate. Intangible assets are simply the access to credit, social capital, cultural capital, political capital, and human capital.

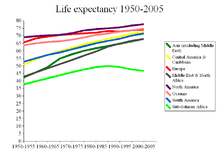

The absolute poverty measure trends are supported by human development indicators, which have also been improving. Life expectancy has greatly increased in the developing world since World War II and is starting to close the gap to the developed world. Child mortality has decreased in every developing region of the world.[56] The proportion of the world's population living in countries where per-capita food supplies are less than 2,200 calories (9,200 kilojoules) per day decreased from 56% in the mid-1960s to below 10% by the 1990s. Similar trends can be observed for literacy, access to clean water and electricity and basic consumer items.[57]

In the United Kingdom, the second Cameron ministry came under attack for their redefinition of poverty; poverty is no longer classified by a family's income, but as to whether a family is in work or not.[58] Considering that two-thirds of people who found work were accepting wages that are below the living wage (according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation[59]) this has been criticised by anti-poverty campaigners as an unrealistic view of poverty in the United Kingdom.[58]

Global prevalence

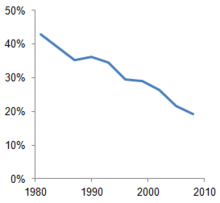

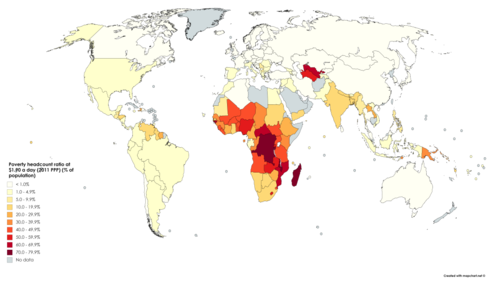

The share of the world's population living in absolute poverty fell from 43% in 1981 to 14% in 2011.[19] The absolute number of people in poverty fell from 1.95 billion in 1981 to 1.01 billion in 2011.[60] The economist Max Roser estimates that the number of people in poverty is therefore roughly the same as 200 years ago.[60] This is the case since the world population was just little more than 1 billion in 1820 and the majority (84% to 94%[61]) of the world population was living poverty. The proportion of the developing world's population living in extreme economic poverty fell from 28 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2001.[19] Most of this improvement has occurred in East and South Asia.[62] In East Asia the World Bank reported that "The poverty headcount rate at the $2-a-day level is estimated to have fallen to about 27 percent [in 2007], down from 29.5 percent in 2006 and 69 percent in 1990."[63] In Sub-Saharan Africa extreme poverty went up from 41 percent in 1981 to 46 percent in 2001,[64] which combined with growing population increased the number of people living in extreme poverty from 231 million to 318 million.[65]

In the early 1990s some of the transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia experienced a sharp drop in income.[66] The collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in large declines in GDP per capita, of about 30 to 35% between 1990 and the through year of 1998 (when it was at its minimum). As a result, poverty rates tripled,[67] excess mortality increased,[68] and life expectancy declined.[69] In subsequent years as per capita incomes recovered the poverty rate dropped from 31.4% of the population to 19.6%.[70][71] The average post-communist country had returned to 1989 levels of per-capita GDP by 2005,[72] although as of 2015 some are still far behind that.[73] According to an article in Foreign Affairs, there were generally three paths to economic reform taken post Soviet collapse. Those nations that took a "radical" or "gradual" reform rate have GDP per capita similar to other nations in their stage of economic development at generally 150% of their transition year (1991) GDP. Nations that took a "slow" approach (an approach that limited free market reforms generally) had much slower, and lower economic growth, higher Gini coefficients, and poorer health outcomes. Currently, those nations sit at 125% of their transition year GDP per capita.[74] A 2009 study published in The Lancet suggested that radical economic changes and the resulting short term unemployment led to temporary increases in the mortality rate of adult males.[75]

World Bank data shows that the percentage of the population living in households with consumption or income per person below the poverty line has decreased in each region of the world except Middle East and North Africa since 1990:[76][77]

| Region | $1 per day | $1.25 per day[78] | $1.90 per day[79] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2002 | 2004 | 1981 | 2008 | 1981 | 1990 | 1999 | 2010 | 2015 | 2018 | |

| East Asia and Pacific | 15.4% | 12.3% | 9.1% | 77.2% | 14.3% | 80.5% | 61.3% | 38.5% | 11.2% | 2.3% | 1.3% |

| Europe and Central Asia | 3.6% | 1.3% | 1.0% | 1.9% | 0.5% | — | — | 7.8% | 2.5% | 1.6% | 1.2% |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 9.6% | 9.1% | 8.6% | 11.9% | 6.5% | 13.8% | 15.2% | 13.7% | 6.2% | 4.1% | 4.4% |

| Middle East and North Africa | 2.1% | 1.7% | 1.5% | 9.6% | 2.7% | — | 6.1% | 3.8% | 2% | 3.8% | 7.2% |

| South Asia | 35.0% | 33.4% | 30.8% | 61.1% | 36% | 55.9% | 47.4% | — | 24.6% | — | — |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 46.1% | 42.6% | 41.1% | 51.5% | 47.5% | — | 54.9% | 58.4% | 46.6% | 42.3% | — |

| World | — | — | — | 52.2% | 22.4% | 42.3% | 36% | 28.6% | 15.7% | 10% | — |

According to Chen and Ravallion, about 1.76 billion people in developing world lived above $1.25 per day and 1.9 billion people lived below $1.25 per day in 1981. The world's population increased over the next 25 years. In 2005, about 4.09 billion people in developing world lived above $1.25 per day and 1.4 billion people lived below $1.25 per day (both 1981 and 2005 data are on inflation adjusted basis).[80][81] Some scholars caution that these trends are subject to various assumptions and not certain. Additionally, they note that the poverty reduction is not uniform across the world; economically prospering countries such as China, India and Brazil have made more progress in absolute poverty reduction than countries in other regions of the world.[82]

In 2012 it was estimated that, using a poverty line of $1.25 a day, 1.2 billion people lived in poverty.[83] Given the current economic model, built on GDP, it would take 100 years to bring the world's poorest up to the poverty line of $1.25 a day.[84] UNICEF estimates half the world's children (or 1.1 billion) live in poverty.[85]

The World Bank forecasted in 2015 that 702.1 million people were living in extreme poverty, down from 1.75 billion in 1990.[86] Extreme poverty is observed in all parts of the world, including developed economies.[87][88] Of the 2015 population, about 347.1 million people (35.2%) lived in Sub-Saharan Africa and 231.3 million (13.5%) lived in South Asia. According to the World Bank, between 1990 and 2015, the percentage of the world's population living in extreme poverty fell from 37.1% to 9.6%, falling below 10% for the first time.[89] The People's Republic of China accounts for over three quarters of global poverty reduction from 1990 to 2005. Though, as noted, China accounted for nearly half of all extreme poverty in 1990.[90] In public opinion around the world people surveyed tend to incorrectly think extreme poverty has not decreased.[91][92]

During the 2013 to 2015 period The World Bank reported that extreme poverty fell from 11% to 10%, however they also noted that the rate of decline had slowed by nearly half from the 25 year average with parts of sub-saharan Africa returning to early 2000 levels.[93][94] The World Bank attributed this to increasing violence following the Arab Spring, population increases in Sub-Saharan Africa, and general African inflationary pressures and economic malaise were the primary drivers for this slow down.[95][96]

There is disagreement among experts as to what would be considered a realistic poverty rate with one considering it "an inaccurately measured and arbitrary cut off".[97] Some contend that a higher poverty line is needed, such as a minimum of $7.40 or even $10 to $15 a day. They argue that these levels would better reflect the cost of basic needs and normal life expectancy.[98] One estimate places the true scale of poverty much higher than the World Bank, with an estimated 4.3 billion people (59% of the world's population) living with less than $5 a day and unable to meet basic needs adequately.[99] It has been argued by some academics that the neoliberal policies promoted by global financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank are actually exacerbating both inequality and poverty.[100][101]

An data based scientific empirical research, which studied the impact of dynastic politics on the level of poverty of the provinces, found a positive correlation between dynastic politics and poverty i.e. the higher proportion of dynastic politicians in power in a province leads to higher poverty rate.[102] There is significant evidence that these political dynasties use their political dominance over their respective regions to enrich themselves, using methods such as graft or outright bribery of legislators.[103]

According to Philip Alston's final report as UN's special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights (July 2020), the World Bank’s international poverty line of $1.90 a day is fundamentally flawed, and has allowed for "self congratulatory" triumphalism in the fight against extreme global poverty, which he asserts is "completely off track" with opportunities being squandered, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Alston, nearly half of the global population, or 3.4 billion, lives on less than $5.50 a day, and this number has barely moved since 1990.[104]

Characteristics

The effects of poverty may also be causes as listed above, thus creating a "poverty cycle" operating across multiple levels, individual, local, national and global.

Impact on health and mortality

One third of deaths around the world – some 18 million people a year or 50,000 per day – are due to poverty-related causes. People living in developing nations, among them women and children, are over represented among the global poor and these effects of severe poverty.[105][106][107] Those living in poverty suffer disproportionately from hunger or even starvation and disease, as well as lower life expectancy.[108][109] According to the World Health Organization, hunger and malnutrition are the single gravest threats to the world's public health and malnutrition is by far the biggest contributor to child mortality, present in half of all cases.[110]

Almost 90% of maternal deaths during childbirth occur in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, compared to less than 1% in the developed world.[111] Those who live in poverty have also been shown to have a far greater likelihood of having or incurring a disability within their lifetime.[112] Infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis can perpetuate poverty by diverting health and economic resources from investment and productivity; malaria decreases GDP growth by up to 1.3% in some developing nations and AIDS decreases African growth by 0.3–1.5% annually.[113][114][115]

Poverty has been shown to impede cognitive function. One way in which this may happen is that financial worries put a severe burden on one's mental resources so that they are no longer fully available for solving complicated problems. The reduced capability for problem solving can lead to suboptimal decisions and further perpetuate poverty.[116] Many other pathways from poverty to compromised cognitive capacities have been noted, from poor nutrition and environmental toxins to the effects of stress on parenting behavior, all of which lead to suboptimal psychological development.[117][118] Neuroscientists have documented the impact of poverty on brain structure and function throughout the lifespan.[119]

Infectious diseases continue to blight the lives of the poor across the world. 36.8 million people are living with HIV/AIDS, with 954,492 deaths in 2017.[120] Every year there are 350–500 million cases of malaria, with 1 million fatalities: Africa accounts for 90 percent of malarial deaths and African children account for over 80 percent of malaria victims worldwide.[121]

Poor people often are more prone to severe diseases due to the lack of health care, and due to living in non-optimal conditions. Among the poor, girls tend to suffer even more due to gender discrimination. Economic stability is paramount in a poor household otherwise they go in an endless loop of negative income trying to treat diseases. Often time when a person in a poor household falls ill it is up to the family members to take care of their family members due to limited access to health care and lack of health insurance. The household members oftentimes have to give up their income or stop seeking further education to tend to the sick member. There is a greater opportunity cost imposed on the poor to tend to someone compared to someone with better financial stability.[122]

Hunger

Rises in the costs of living make poor people less able to afford items. Poor people spend a greater portion of their budgets on food than wealthy people. As a result, poor households and those near the poverty threshold can be particularly vulnerable to increases in food prices. For example, in late 2007 increases in the price of grains[123] led to food riots in some countries.[124][125][126] The World Bank warned that 100 million people were at risk of sinking deeper into poverty.[127] Threats to the supply of food may also be caused by drought and the water crisis.[128] Intensive farming often leads to a vicious cycle of exhaustion of soil fertility and decline of agricultural yields.[129] Approximately 40% of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded.[130][131] In Africa, if current trends of soil degradation continue, the continent might be able to feed just 25% of its population by 2025, according to United Nations University's Ghana-based Institute for Natural Resources in Africa.[132] Every year nearly 11 million children living in poverty die before their fifth birthday. 1.02 billion people go to bed hungry every night.[133]

According to the Global Hunger Index, Sub-Saharan Africa had the highest child malnutrition rate of the world's regions over the 2001–2006 period.[134]

The Associated Press reports that people gather every evening in downtown Caracas in search of food thrown out on sidewalks due to 90% of Venezuela's population living in poverty.[135]

Efforts to end hunger and undernutrition

As part of the Sustainable Development Goals the global community has made the elimination of hunger and undernutrition a priority for the coming years. While the Goal 2 of the SDGs aims to reach this goal by 2030[136] a number of initiatives aim to achieve the goal 5 years earlier, by 2025:

- The partnership Compact2025, led by IFPRI with the involvement of UN organisations, NGOs and private foundations[137] develops and disseminates evidence-based advice to politicians and other decision-makers aimed at ending hunger and undernutrition in the coming 10 years, by 2025.[138] It bases its claim that hunger can be ended by 2025 on a report by Shenggen Fan and Paul Polman that analyzed the experiences from China, Vietnam, Brazil and Thailand.[139]

- The European Union and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have launched a partnership to combat undernutrition in June 2015. The program will initiatilly be implemented in Bangladesh, Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Laos and Niger and will help these countries to improve information and analysis about nutrition so they can develop effective national nutrition policies.[140]

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN has created a partnership that will act through the African Union's CAADP framework aiming to end hunger in Africa by 2025. It includes different interventions including support for improved food production, a strengthening of social protection and integration of the right to food into national legislation.[141]

Education

Research has found that there is a high risk of educational underachievement for children who are from low-income housing circumstances. This is often a process that begins in primary school for some less fortunate children. Instruction in the US educational system, as well as in most other countries, tends to be geared towards those students who come from more advantaged backgrounds. As a result, children in poverty are at a higher risk than advantaged children for retention in their grade, special deleterious placements during the school's hours and even not completing their high school education.[142] Advantage breeds advantage.[143] There are indeed many explanations for why students tend to drop out of school. One is the conditions of which they attend school. Schools in poverty-stricken areas have conditions that hinder children from learning in a safe environment. Researchers have developed a name for areas like this: an urban war zone is a poor, crime-laden district in which deteriorated, violent, even war-like conditions and underfunded, largely ineffective schools promote inferior academic performance, including irregular attendance and disruptive or non-compliant classroom behavior.[144] Because of poverty, "Students from low-income families are 2.4 times more likely to drop out than middle-income kids, and over 10 times more likely than high-income peers to drop out"[145]

For children with low resources, the risk factors are similar to others such as juvenile delinquency rates, higher levels of teenage pregnancy, and the economic dependency upon their low-income parent or parents.[142] Families and society who submit low levels of investment in the education and development of less fortunate children end up with less favorable results for the children who see a life of parental employment reduction and low wages. Higher rates of early childbearing with all the connected risks to family, health and well-being are major important issues to address since education from preschool to high school are both identifiably meaningful in a life.[142]

Poverty often drastically affects children's success in school. A child's "home activities, preferences, mannerisms" must align with the world and in the cases that they do not do these, students are at a disadvantage in the school and, most importantly, the classroom.[146] Therefore, it is safe to state that children who live at or below the poverty level will have far less success educationally than children who live above the poverty line. Poor children have a great deal less healthcare and this ultimately results in many absences from the academic year. Additionally, poor children are much more likely to suffer from hunger, fatigue, irritability, headaches, ear infections, flu, and colds.[146] These illnesses could potentially restrict a child or student's focus and concentration.[147]

For a child to grow up emotionally healthy, the children under three need "A strong, reliable primary caregiver who provides consistent and unconditional love, guidance, and support. Safe, predictable, stable environments. Ten to 20 hours each week of harmonious, reciprocal interactions. This process, known as attunement, is most crucial during the first 6–24 months of infants' lives and helps them develop a wider range of healthy emotions, including gratitude, forgiveness, and empathy. Enrichment through personalized, increasingly complex activities".

Harmful spending habits mean that the poor typically spend about 2 percent of their income educating their children but larger percentages of alcohol and tobacco (For example, 6 percent in Indonesia and 8 percent in Mexico).[148]

Gender and poverty

In general, the interaction of gender with poverty or location tends to work to the disadvantage of girls in poorer countries with low completion rates and social expectations that they marry early, and to the disadvantage of boys in richer countries with high completion rates but social expectations that they enter the labour force early.[149] At the primary education level, most countries with a completion rate below 60% exhibit gender disparity at girls’ expense, particularly poor and rural girls. In Mauritania, the adjusted gender parity index is 0.86 on average, but only 0.63 for the poorest 20%, while there is parity among the richest 20%. In countries with completion rates between 60% and 80%, gender disparity is generally smaller, but disparity at the expense of poor girls is especially marked in Cameroon, Nigeria and Yemen. Exceptions in the opposite direction are observed in countries with pastoralist economies that rely on boys’ labour, such as the Kingdom of Eswatini, Lesotho and Namibia.[149]

Shelter

Poverty increases the risk of homelessness.[151] Slum-dwellers, who make up a third of the world's urban population, live in a poverty no better, if not worse, than rural people, who are the traditional focus of the poverty in the developing world, according to a report by the United Nations.[152]

There are over 100 million street children worldwide.[153] Most of the children living in institutions around the world have a surviving parent or close relative, and they most commonly entered orphanages because of poverty.[150] It is speculated that, flush with money, orphanages are increasing and push for children to join even though demographic data show that even the poorest extended families usually take in children whose parents have died.[150] Experts and child advocates maintain that orphanages are expensive and often harm children's development by separating them from their families and that it would be more effective and cheaper to aid close relatives who want to take in the orphans.[150]

Utilities

Water and sanitation

As of 2012, 2.5 billion people lack access to sanitation services and 15% practice open defecation.[154] The most noteworthy example is Bangladesh, which has half the GDP per capita of India but has a lower mortality from diarrhea than India or the world average, with diarrhea deaths declining by 90% since the 1990s. Even while providing latrines is a challenge, people still do not use them even when available. By strategically providing pit latrines to the poorest, charities in Bangladesh sparked a cultural change as those better off perceived it as an issue of status to not use one. The vast majority of the latrines built were then not from charities but by villagers themselves.[155]

Water utility subsidies tend to subsidize water consumption by those connected to the supply grid, which is typically skewed towards the richer and urban segment of the population and those outside informal housing. As a result of heavy consumption subsidies, the price of water decreases to the extent that only 30%, on average, of the supplying costs in developing countries is covered.[156][157] This results in a lack of incentive to maintain delivery systems, leading to losses from leaks annually that are enough for 200 million people.[156][158] This also leads to a lack of incentive to invest in expanding the network, resulting in much of the poor population being unconnected to the network. Instead, the poor buy water from water vendors for, on average, about five to 16 times the metered price.[156][159] However, subsidies for laying new connections to the network rather than for consumption have shown more promise for the poor.[157]

Electricity

Similarly, the poorest fifth receive 0.1% of the world's lighting but pay a fifth of total spending on light, accounting for 25 to 30 percent of their income.[160] Indoor air pollution from burning fuels kills 2 million, with almost half the deaths from pneumonia in children under 5.[161] Fuel from Bamboo burns more cleanly and also matures much faster than wood, thus also reducing deforestation.[161] Additionally, using solar panels is promoted as being cheaper over the products' lifetime even if upfront costs are higher.[160] Thus, payment schemes such as lend-to-own programs are promoted and up to 14% of Kenyan households use solar as their primary energy source.[162]

Violence

According to experts, many women become victims of trafficking, the most common form of which is prostitution, as a means of survival and economic desperation.[163] Deterioration of living conditions can often compel children to abandon school to contribute to the family income, putting them at risk of being exploited.[164] For example, in Zimbabwe, a number of girls are turning to sex in return for food to survive because of the increasing poverty.[165] According to studies, as poverty decreases there will be fewer and fewer instances of violence.[166]

In one survey, 67% of children from disadvantaged inner cities said they had witnessed a serious assault, and 33% reported witnessing a homicide.[167] 51% of fifth graders from New Orleans (median income for a household: $27,133) have been found to be victims of violence, compared to 32% in Washington, DC (mean income for a household: $40,127).[168]

Personality

Max Weber and some schools of modernization theory suggest that cultural values could affect economic success.[169][170] However, researchers have gathered evidence that suggest that values are not as deeply ingrained and that changing economic opportunities explain most of the movement into and out of poverty, as opposed to shifts in values.[171] Studies have shown that poverty changes the personalities of children who live in it. The Great Smoky Mountains Study was a ten-year study that was able to demonstrate this. During the study, about one-quarter of the families saw a dramatic and unexpected increase in income. The study showed that among these children, instances of behavioral and emotional disorders decreased, and conscientiousness and agreeableness increased.[172]

One 2012 paper, based on a sampling of 9,646 U.S, adults, claimed that poverty tends to correlate with laziness and other such traits.[173] A 2018 report on poverty in the United States by UN special rapporteur Philip Alston asserts that caricatured narratives about the rich and the poor, that "the rich are industrious, entrepreneurial, patriotic and the drivers of economic success. The poor are wasters, losers and scammers" are largely inaccurate, as "the poor are overwhelmingly those born into poverty, or those thrust there by circumstances largely beyond their control, such as physical or mental disabilities, divorce, family breakdown, illness, old age, unliveable wages or discrimination in the job market."[174]

A psychological study has been conducted by four scientists during inaugural Convention of Psychological Science. The results find that people who thrive with financial stability or fall under low socioeconomic status (SES), tend to perform worse cognitively due to external pressure imposed upon them. The research found that stressors such as low income, inadequate health care, discrimination, exposure to criminal activities all contribute to mental disorders. This study also found that it slows cognitive thinking in children when they are exposed to poverty stricken environments.[175] In kids it is seen that kids perform better under the care and nourishment from their parents, and found that children tend to adopt speaking language at a younger age. Since being in poverty from childhood is especially more harmful than it is for an adult, therefore it is seen that children in poor households tend to fall behind in certain cognitive abilities compared to other average families.[176]

Discrimination

Cultural factors, such as discrimination of various kinds, can negatively affect productivity such as age discrimination, stereotyping,[177] discrimination against people with physical disability,[178] gender discrimination, racial discrimination, and caste discrimination. Women are the group suffering from the highest rate of poverty after children; 14.5% of women and 22% of children are poor in the United States. In addition, the fact that women are more likely to be caregivers, regardless of income level, to either the generations before or after them, exacerbates the burdens of their poverty.[179] Marking the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty Philip Alston warned in a statement that, “The world’s poor are at disproportionate risk of torture, arrest, early death and domestic violence, but their civil and political rights are being airbrushed out of the picture.” ... people in lower socio-economic classes are much more likely to get killed, tortured or experience an invasion of their privacy, and are far less likely to realize their right to vote, or otherwise participate in the political process.”[180]

Causes of poverty

Causes of poverty is a highly ideologically charged subject, as different causes point to different remedies. Very broadly speaking, the socialist tradition locates the roots of poverty in problems of distribution and the use of the means of production as capital benefiting individuals, and calls for re-distribution of wealth as the solution, whereas the neoliberal school of thought is dedicated the idea that creating conditions for profitable private investment is the solution. Neoliberal think tanks have received extensive funding,[181] and the ability to apply many of their ideas in highly indebted countries in the global South as a condition for receiving emergency loans from the International Monetary Fund.

Poverty reduction

Various poverty reduction strategies are broadly categorized based on whether they make more of the basic human needs available or whether they increase the disposable income needed to purchase those needs. Some strategies such as building roads can both bring access to various basic needs, such as fertilizer or healthcare from urban areas, as well as increase incomes, by bringing better access to urban markets. Statistics of 2018 shows population living in extreme conditions has declined by more than 1 billion in the last 25 years. As per the report published by the world bank on 19 September 2018 world poverty falls below 750 million.[182]

Increasing the supply of basic needs

Food and other goods

Agricultural technologies such as nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides, new seed varieties and new irrigation methods have dramatically reduced food shortages in modern times by boosting yields past previous constraints.[183]

Before the Industrial Revolution, poverty had been mostly accepted as inevitable as economies produced little, making wealth scarce.[184] Geoffrey Parker wrote that "In Antwerp and Lyon, two of the largest cities in western Europe, by 1600 three-quarters of the total population were too poor to pay taxes, and therefore likely to need relief in times of crisis."[185] The initial industrial revolution led to high economic growth and eliminated mass absolute poverty in what is now considered the developed world.[186] Mass production of goods in places such as rapidly industrializing China has made what were once considered luxuries, such as vehicles and computers, inexpensive and thus accessible to many who were otherwise too poor to afford them.[187][188]

Even with new products, such as better seeds, or greater volumes of them, such as industrial production, the poor still require access to these products. Improving road and transportation infrastructure helps solve this major bottleneck. In Africa, it costs more to move fertilizer from an African seaport 60 miles inland than to ship it from the United States to Africa because of sparse, low-quality roads, leading to fertilizer costs two to six times the world average.[189] Microfranchising models such as door to door distributors who earn commission-based income or Coca-Cola's successful distribution system[190][191] are used to disseminate basic needs to remote areas for below market prices.[192][193]

Health care and education

Nations do not necessarily need wealth to gain health.[194] For example, Sri Lanka had a maternal mortality rate of 2% in the 1930s, higher than any nation today.[195] It reduced it to 0.5–0.6% in the 1950s and to 0.6% today while spending less each year on maternal health because it learned what worked and what did not.[195] Knowledge on the cost effectiveness of healthcare interventions can be elusive and educational measures have been made to disseminate what works, such as the Copenhagen Consensus.[196] Cheap water filters and promoting hand washing are some of the most cost effective health interventions and can cut deaths from diarrhea and pneumonia.[197][198]

Strategies to provide education cost effectively include deworming children, which costs about 50 cents per child per year and reduces non-attendance from anemia, illness and malnutrition, while being only a twenty-fifth as expensive as increasing school attendance by constructing schools.[199] Schoolgirl absenteeism could be cut in half by simply providing free sanitary towels.[200] Fortification with micronutrients was ranked the most cost effective aid strategy by the Copenhagen Consensus.[201] For example, iodised salt costs 2 to 3 cents per person a year while even moderate iodine deficiency in pregnancy shaves off 10 to 15 IQ points.[202] Paying for school meals is argued to be an efficient strategy in increasing school enrollment, reducing absenteeism and increasing student attention.[203]

Desirable actions such as enrolling children in school or receiving vaccinations can be encouraged by a form of aid known as conditional cash transfers.[204] In Mexico, for example, dropout rates of 16- to 19-year-olds in rural area dropped by 20% and children gained half an inch in height.[205] Initial fears that the program would encourage families to stay at home rather than work to collect benefits have proven to be unfounded. Instead, there is less excuse for neglectful behavior as, for example, children stopped begging on the streets instead of going to school because it could result in suspension from the program.[205]

Removing constraints on government services

Government revenue can be diverted away from basic services by corruption.[206][207] Funds from aid and natural resources are often sent by government individuals for money laundering to overseas banks which insist on bank secrecy, instead of spending on the poor.[208] A Global Witness report asked for more action from Western banks as they have proved capable of stanching the flow of funds linked to terrorism.[208]

Illicit capital flight from the developing world is estimated at ten times the size of aid it receives and twice the debt service it pays,[209] with one estimate that most of Africa would be developed if the taxes owed were paid.[210] About 60 per cent of illicit capital flight from Africa is from transfer mispricing, where a subsidiary in a developing nation sells to another subsidiary or shell company in a tax haven at an artificially low price to pay less tax.[211] An African Union report estimates that about 30% of sub-Saharan Africa's GDP has been moved to tax havens.[212] Solutions include corporate "country-by-country reporting" where corporations disclose activities in each country and thereby prohibit the use of tax havens where no effective economic activity occurs.[211]

Developing countries' debt service to banks and governments from richer countries can constrain government spending on the poor.[213] For example, Zambia spent 40% of its total budget to repay foreign debt, and only 7% for basic state services in 1997.[214] One of the proposed ways to help poor countries has been debt relief. Zambia began offering services, such as free health care even while overwhelming the health care infrastructure, because of savings that resulted from a 2005 round of debt relief.[215]

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as primary holders of developing countries' debt, attach structural adjustment conditionalities in return for loans which are generally geared toward loan repayment with austerity measures such as the elimination of state subsidies and the privatization of state services. For example, the World Bank presses poor nations to eliminate subsidies for fertilizer even while many farmers cannot afford them at market prices.[216] In Malawi, almost five million of its 13 million people used to need emergency food aid but after the government changed policy and subsidies for fertilizer and seed were introduced, farmers produced record-breaking corn harvests in 2006 and 2007 as Malawi became a major food exporter.[216] A major proportion of aid from donor nations is tied, mandating that a receiving nation spend on products and expertise originating only from the donor country.[217] US law requires food aid be spent on buying food at home, instead of where the hungry live, and, as a result, half of what is spent is used on transport.[218]

Distressed securities funds, also known as vulture funds, buy up the debt of poor nations cheaply and then sue countries for the full value of the debt plus interest which can be ten or 100 times what they paid.[219] They may pursue any companies which do business with their target country to force them to pay to the fund instead.[219] Considerable resources are diverted on costly court cases. For example, a court in Jersey ordered the Democratic Republic of the Congo to pay an American speculator $100 million in 2010.[219] Now, the UK, Isle of Man and Jersey have banned such payments.[219]

.jpg)

Reversing brain drain

The loss of basic needs providers emigrating from impoverished countries has a damaging effect.[220] As of 2004, there were more Ethiopia-trained doctors living in Chicago than in Ethiopia.[221] Proposals to mitigate the problem include compulsory government service for graduates of public medical and nursing schools[220] and promoting medical tourism so that health care personnel have more incentive to practice in their home countries.[222] It is very easy for Ugandan doctors to emigrate to other countries. It is seen that only 69 percent of the health care jobs were filled in Uganda. Other Ugandan doctors were seeking jobs in other countries leaving inadequate or less skilled doctors to stay in Uganda.[223]

Controlling overpopulation

Some argue that overpopulation and lack of access to birth control can lead to population increase to exceed food production and other resources.[224][65][225][226] Better education for both men and women, and more control of their lives, reduces population growth due to family planning.[227] According to United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), by giving better education to men and women, they can earn money for their lives and can help them to strengthen economic security.[228]

Increasing personal income

The following are strategies used or proposed to increase personal incomes among the poor. Raising farm incomes is described as the core of the antipoverty effort as three-quarters of the poor today are farmers.[229] Estimates show that growth in the agricultural productivity of small farmers is, on average, at least twice as effective in benefiting the poorest half of a country's population as growth generated in nonagricultural sectors.[230]

Income grants

A guaranteed minimum income ensures that every citizen will be able to purchase a desired level of basic needs. A basic income (or negative income tax) is a system of social security, that periodically provides each citizen, rich or poor, with a sum of money that is sufficient to live on. Studies of large cash-transfer programs in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Malawi show that the programs can be effective in increasing consumption, schooling, and nutrition, whether they are tied to such conditions or not.[231][232][233] Proponents argue that a basic income is more economically efficient than a minimum wage and unemployment benefits, as the minimum wage effectively imposes a high marginal tax on employers, causing losses in efficiency. In 1968, Paul Samuelson, John Kenneth Galbraith and another 1,200 economists signed a document calling for the US Congress to introduce a system of income guarantees.[234] Winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics, with often diverse political convictions, who support a basic income include Herbert A. Simon,[235] Friedrich Hayek,[236] Robert Solow,[235] Milton Friedman,[237] Jan Tinbergen,[235] James Tobin[238][239][240] and James Meade.[235]

Income grants are argued to be vastly more efficient in extending basic needs to the poor than subsidizing supplies whose effectiveness in poverty alleviation is diluted by the non-poor who enjoy the same subsidized prices.[241] With cars and other appliances, the wealthiest 20% of Egypt uses about 93% of the country's fuel subsidies.[242] In some countries, fuel subsidies are a larger part of the budget than health and education.[242][243] A 2008 study concluded that the money spent on in-kind transfers in India in a year could lift all India's poor out of poverty for that year if transferred directly.[244] The primary obstacle argued against direct cash transfers is the impractically for poor countries of such large and direct transfers. In practice, payments determined by complex iris scanning are used by war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo and Afghanistan,[245] while India is phasing out its fuel subsidies in favor of direct transfers.[246] Additionally, in aid models, the famine relief model increasingly used by aid groups calls for giving cash or cash vouchers to the hungry to pay local farmers instead of buying food from donor countries, often required by law, as it wastes money on transport costs.[247][248]

Economic freedoms

Corruption often leads to many civil services being treated by governments as employment agencies to loyal supporters[249] and so it could mean going through 20 procedures, paying $2,696 in fees, and waiting 82 business days to start a business in Bolivia, while in Canada it takes two days, two registration procedures, and $280 to do the same.[250] Such costly barriers favor big firms at the expense of small enterprises, where most jobs are created.[251] Often, businesses have to bribe government officials even for routine activities, which is, in effect, a tax on business.[252] Noted reductions in poverty in recent decades has occurred in China and India mostly as a result of the abandonment of collective farming in China and the ending of the central planning model known as the License Raj in India.[253][254][255]

The World Bank concludes that governments and feudal elites extending to the poor the right to the land that they live and use are 'the key to reducing poverty' citing that land rights greatly increase poor people's wealth, in some cases doubling it.[256] Although approaches varied, the World Bank said the key issues were security of tenure and ensuring land transactions costs were low.[256]

Greater access to markets brings more income to the poor. Road infrastructure has a direct impact on poverty.[257][258] Additionally, migration from poorer countries resulted in $328 billion sent from richer to poorer countries in 2010, more than double the $120 billion in official aid flows from OECD members. In 2011, India got $52 billion from its diaspora, more than it took in foreign direct investment.[259]

Financial services

Microloans, made famous by the Grameen Bank, is where small amounts of money are loaned to farmers or villages, mostly women, who can then obtain physical capital to increase their economic rewards. However, microlending has been criticized for making hyperprofits off the poor even from its founder, Muhammad Yunus,[260] and in India, Arundhati Roy asserts that some 250,000 debt-ridden farmers have been driven to suicide.[261][262][263]

There has been significant rise of agriculture and small business that started booming up after the introduction of Grameen Banking especially in the rural areas. While making the foundation of this loan, from 1984 to 1989 loan recovery decreased from 99.4 percent to 96.9 percent.[264]

Those in poverty place overwhelming importance on having a safe place to save money, much more so than receiving loans.[265] Additionally, a large part of microfinance loans are spent not on investments but on products that would usually be paid by a checking or savings account.[265] Microsavings are designs to make savings products available for the poor, who make small deposits. Mobile banking utilizes the wide availability of mobile phones to address the problem of the heavy regulation and costly maintenance of saving accounts.[265] This usually involves a network of agents of mostly shopkeepers, instead of bank branches, would take deposits in cash and translate these onto a virtual account on customers' phones. Cash transfers can be done between phones and issued back in cash with a small commission, making remittances safer.[266]

Financial services in US

In USA there are abundance of payday loan companies that strive to serve those people whose credit scores are much below the standard credit score in order to take an eligible loan. While these companies initially gives money to people who would likely default from traditional loans, many still frown on these loan services due to charging astonishingly high interest rates.

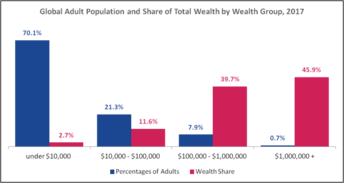

Wealth concentration

%2C_2018.jpg)

Poverty can also be reduced as an improved economic policy is developed by the governing authorities to facilitate a more equitable distribution of the nation's wealth. Oxfam has called for an international movement to end extreme wealth concentration as a significant step towards ameliorating global poverty. The group stated that the $240 billion added to the fortunes of the world's richest billionaires in 2012 was enough to end extreme poverty four times over. Oxfam argues that the "concentration of resources in the hands of the top 1% depresses economic activity and makes life harder for everyone else – particularly those at the bottom of the economic ladder."[267][268] It has been reported that only 1% of the world population controls 50% of the wealth today, and the other 99% is having access to the remaining 50% only, and the gap has sharply increased in the recent past.[269] In 2018, Oxfam reported that the gains of the world's billionaires in 2017, which amounted to $762 billion, was enough to end extreme global poverty seven times over.[270]

José Antonio Ocampo, professor at Columbia University and former finance minister of Colombia, and Magdalena Sepúlveda Carmona, former UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, argue that global tax reform is integral to human development and fighting poverty, as corporate tax avoidance has disproportionately impacted those mired in poverty, noting that "the human impact is devastatingly real. When profits are shifted out, the tax revenues from those profits that could be available to fund healthcare, schools, water sanitation and other public goods vanish from the ledger, leaving women and men, boys and girls without pathways to a better future."[271]

Raghuram G. Rajan, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund and professor of finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business has blamed the ever-widening gulf between the rich and the poor especially in the US to be one of the main Fault Lines which caused the financial institutions to pump money into subprime mortgages – on political behest, as a palliative and not a remedy, for poverty – causing the financial crisis of 2007–2009. In Rajan's view the main cause of increasing gap between the high income and low income earners, was lack of equal access to high class education for the latter.[272]

The existence of inequality is in part due to a set of self-reinforcing behaviors that all together constitute one aspect of the cycle of poverty. These behaviors, in addition to unfavorable, external circumstances, also explain the existence of the Matthew effect, which not only exacerbates existing inequality, but is more likely to make it multigenerational. Widespread, multigenerational poverty is an important contributor to civil unrest and political instability.[273]

Business solutions to poverty

Serving the poor market

The concept of business serving the world's poorest four billion or so people has been popular since CK Prahalad introduced the idea through his book Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits in 2004, among many business corporations and business schools.[274][275] Kash Rangan, John Quelch, and other faculty members at the Global Poverty Project at Harvard Business School "believe that in pursuing its own self-interest in opening and expanding the BoP market, business can make a profit while serving the poorest of consumers and contributing to development."[276] According to Rangan "For business, the bulk of emerging markets worldwide is at the bottom of the pyramid so it makes good business sense – not a sense of do-gooding – to go after it.".[276]

In their 2013 book, "The Business Solution to Poverty," Paul Polak and Mal Warwick directly addressed the criticism leveled against Prahalad's concept.[277] They noted that big business often failed to create products that actually met the needs and desires of the customers who lived at the bottom-of-the-pyramid. Their answer was that a business that wanted to succeed in that market had to spend time talking to and understanding those customers. Polak had previously promoted this approach in his previous book, "Out of Poverty," that described the work of International Development Enterprises (iDE), which he had formed in 1982.[278] Polak and Warwick provided practical advice: a product needed to affect at least a billion people (i.e., have universal appeal), it had to be able to be delivered to customers living where there was not a FedEx office or even a road, and it had to be "radically affordable" to attract someone who earned less than $2 a day.

Creating entrepreneurs

Rather than encouraging multinational businesses to meet the needs of the poor, some organizations such as iDE, the World Resources Institute, and the United Nations Development Programme began to focus on working directly with helping bottom-of-the-pyramid populations become local, small-scale entrepreneurs.[280] Since so much of this population is engaged in agriculture, these NGOs have addressed market gaps that enable small-scale (i.e., plots less than 2 hectares) farmers to increase their production and find markets for their harvests. This is done by increasing the availability of farming equipment (e.g., pumps, tillers, seeders) and better quality seed and fertilizer, as well as expanding access for training in farming best practices (e.g., crop rotation).

Creating entrepreneurs through microfinance can produce unintended outcomes: Some entrepreneurial borrowers become informal intermediaries between microfinance initiatives and poorer micro-entrepreneurs. Those who more easily qualify for microfinance split loans into smaller credit to even poorer borrowers. Informal intermediation ranges from casual intermediaries at the good or benign end of the spectrum to 'loan sharks' at the professional and sometimes criminal end of the spectrum.[281]

Criticisms of this approach

Milton Friedman argues that the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits only,[282] thus, it needs to be examined whether business in BoP markets is capable of achieving the dual objective of making a profit while serving the poorest of consumers and contributing to development? Erik Simanis has reported that the model has a fatal flaw. According to Erik "Despite achieving healthy penetration rates of 5% to 10% in four test markets, for instance, Procter & Gamble couldn't generate a competitive return on its Pur water-purification powder after launching the product on a large scale in 2001...DuPont ran into similar problems with a venture piloted from 2006 to 2008 in Andhra Pradesh, India, by its subsidiary Solae, a global manufacturer of soy protein ... Because the high costs of doing business among the very poor demand a high contribution per transaction, companies must embrace the reality that high margins and price points aren't just a top-of-the-pyramid phenomenon; they're also a necessity for ensuring sustainable businesses at the bottom of the pyramid."[283] Marc Gunther states that "The bottom-of-the-pyramid (BOP) market leader, arguably, is Unilever ... Its signature BOP product is Pureit, a countertop water-purification system sold in India, Africa and Latin America. It's saving lives, but it's not making money for shareholders."[275] This leaves the ideal of eradicating poverty through profits or with a good business sense – not a sense of do-gooding rather questionable.

Others have noted that relying on BoP consumers to choose to purchase items that increase their incomes is naive. Poor consumers may spend their income disproportionately on events or goods and services that offer short-term benefits rather than invest in things that could change their lives in the long-term.[284]

Environmental issues

A report published in 2013 by the World Bank, with support from the Climate & Development Knowledge Network, found that climate change was likely to hinder future attempts to reduce poverty. The report presented the likely impacts of present day, 2 °C and 4 °C warming on agricultural production, water resources, coastal ecosystems and cities across Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and South East Asia. The impacts of a temperature rise of 2 °C included: regular food shortages in Sub-Saharan Africa; shifting rain patterns in South Asia leaving some parts under water and others without enough water for power generation, irrigation or drinking; degradation and loss of reefs in South East Asia, resulting in reduced fish stocks; and coastal communities and cities more vulnerable to increasingly violent storms.[285] In 2016, a UN report claimed that by 2030, an additional 122 million more people could be driven to extreme poverty because of climate change.[286]

Many think that poverty is the cause of environmental degradation, while there are others who claim that rather the poor are the worst sufferers of environmental degradation caused by reckless exploitation of natural resources by the rich.[287] A Delhi-based environment organisation, the Centre for Science and Environment, points out that if the poor world were to develop and consume in the same manner as the West to achieve the same living standards, "we would need two additional planet Earths to produce resources and absorb wastes.", reports Anup Shah (2003). in his article Poverty and the Environment on Global Issues.[288]

Voluntary poverty

Among some individuals, poverty is considered a necessary or desirable condition, which must be embraced to reach certain spiritual, moral, or intellectual states. Poverty is often understood to be an essential element of renunciation in religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism (only for monks, not for lay persons) and Jainism, whilst in Roman Catholicism it is one of the evangelical counsels. The main aim of giving up things of the materialistic world is to withdraw oneself from sensual pleasures (as they are considered illusionary and only temporary in some religions – such as the concept of dunya in Islam). This self-invited poverty (or giving up pleasures) is different from the one caused by economic imbalance.

Some Christian communities, such as the Simple Way, the Bruderhof, and the Amish value voluntary poverty;[289] some even take a vow of poverty, similar to that of the traditional Catholic orders, in order to live a more complete life of discipleship.[290]

Benedict XVI distinguished "poverty chosen" (the poverty of spirit proposed by Jesus), and "poverty to be fought" (unjust and imposed poverty). He considered that the moderation implied in the former favors solidarity, and is a necessary condition so as to fight effectively to eradicate the abuse of the latter.[291]

As it was indicated above the reduction of poverty results from religion, but also can result from solidarity.[292]

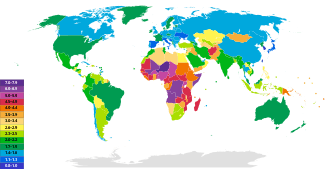

Charts and tables

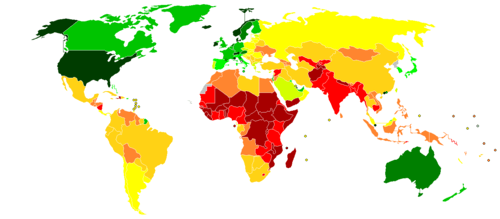

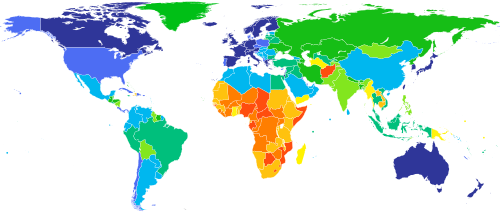

.png)

≥ 0.900 0.850–0.899 0.800–0.849 0.750–0.799 0.700–0.749 |

0.650–0.699 0.600–0.649 0.550–0.599 0.500–0.549 0.450–0.499 |

0.400–0.449 ≤ 0.399 Data unavailable |

See also

- Accumulation by dispossession

- Aporophobia

- Asset poverty

- Basic income

- Bottom of the pyramid

- Causes of poverty

- Climate change and poverty

- Cycle of poverty

- Environmental racism

- Extreme poverty

- Food Bank

- Homelessness

- Human rights

- Hunger

- Hunger in the United Kingdom

- Hunger in the United States

- Income disparity

- International development

- International inequality

- Involuntary unemployment

- Job guarantee

- Juvenilization of poverty

- Les Misérables

- List of countries by percentage of population living in poverty

- Living wage

- Measuring poverty

- Millennium Development Goals

- Poverty threshold

- Poverty trap

- Poverty reduction

- Poverty in the United Kingdom

- Poverty in the United States

- Redistribution of income and wealth

- Relative deprivation

- Social programs

- Social safety net

- United Nations Millennium Declaration

- World Poverty Clock

Sources

![]()

Notes

- In his book The End of Poverty Jeffrey Sachs argued that extreme global poverty could be eliminated by 2025 if the wealthy countries of the world were to increase their combined foreign aid budgets to between $135 billion and $195 billion from 2005 to 2015. In 2004, 1.1 billion people lived in extreme poverty on less than a dollar a day.

References

- "Uttar Pradesh, Poverty, Growth and Inequality" (PDF). worldbank.org. World Bank Group. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Poverty. merriam-webster. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- "Poverty | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Sabates, Ricardo (2008). The Impact of Lifelong Learning on Poverty Reduction (PDF). IFLL Public Value Paper 1. Latimer Trend, Plymouth. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-86201-379-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015.

- "Causes of Poverty – Global Issues". www.globalissues.org. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Walter Skeat (2005). An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-44052-1.

- "Indicators of Poverty & Hunger" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "Poverty and Inequality Analysis". worldbank.org. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- Ravallion, Martin; Chen, Shaohua; Sangraula, Prem (May 2008). Dollar a Day Revisited (PDF) (Report). Washington DC: The World Bank. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Ravallion, Martin; Chen, Shaohua; Sangraula, Prem (2009). "Dollar a day" (PDF). The World Bank Economic Review. 23 (2): 163–84. doi:10.1093/wber/lhp007. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "The Bank uses an updated international poverty line of US $1.90 a day, which incorporates new information on differences in the cost of living across countries (the PPP exchange rates)."

- UN declaration at World Summit on Social Development in Copenhagen in 1995

- "Poverty". World Bank. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- Sachs, Jeffrey D. (30 December 2005). The End of Poverty. Penguin Press. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-59420-045-8. p. 20

- Tanton, Robert (6 July 2009). "Poverty versus inequality". Australian Policy Online. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- Davidson, Peter (2012). Poverty in Australia (PDF) (Report). Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Council of Social Service. ISBN 978-0858710825. ISSN 1326-7124. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- "The Individual Deprivation Measure: Transforming how we measure poverty". The United Nations Live and on Demand. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- Martin Ravallion, Shaohua Chen & Prem Sangraula (2008). "Dollar a Day Revisited" (PDF). The World Bank.

- "The World Bank, 2007, Understanding Poverty". Web.worldbank.org. 19 April 2005. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Devichand, Mukul (2 December 2007). "When a dollar a day means 25 cents". bbcnews.com. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- "Poverty Definitions". US Census Bureau. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "World Bank's $1.25/day poverty measure – countering the latest criticisms". The World Bank. 2010. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- "New Progress in Development-oriented Poverty Reduction Program for Rural China (1,274 yuan per year = US$ 0.55 per day)". The Government of China. 2011.

- "Poverty Measures" (PDF). The World Bank. 2009.

- Amartya Sen (March 1976). "Poverty: An Ordinal Approach to Measurement". Econometrica. 44 (2): 219–31. doi:10.2307/1912718. JSTOR 1912718.

- Raphael, Dennis (June 2009). "Poverty, Human Development, and Health in Canada: Research, Practice, and Advocacy Dilemmas". Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 41 (2): 7–18. PMID 19650510. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Child poverty in rich nations: Report card no. 6 (Report). Innocenti Research Centre. 2005.

- "Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries" (PDF). Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2008.

- Human development report: Capacity development: Empowering people and institutions (Report). Geneva: United Nations Development Program. 2008.

- "Child Poverty". Ottawa, ON: Conference Board of Canada. 2013.