Dracunculiasis

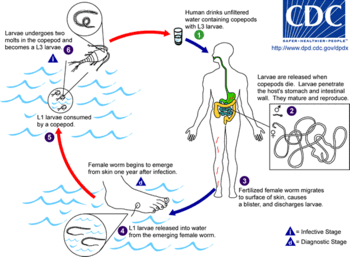

Dracunculiasis, also called Guinea-worm disease (GWD), is a parasitic infection by the Guinea worm.[1] A person becomes infected when they drink water that contains water fleas infected with guinea worm larvae.[1] Initially there are no symptoms.[3] About one year later, the female worm forms a painful blister in the skin, usually on a lower limb.[1] Other symptoms at this time may include vomiting and dizziness.[3] The worm then emerges from the skin over the course of a few weeks.[4] During this time, it may be difficult to walk or work.[3] It is very uncommon for the disease to cause death.[1]

| Dracunculiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Guinea-worm disease (GWD) |

| |

| Using a matchstick to wind up and remove a guinea worm from the leg of a human | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Painful blister on lower leg[1] |

| Usual onset | One year after infection[1] |

| Causes | Guinea worms spread by water fleas[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptom[2] |

| Prevention | Preventing those infected from putting the wound in drinking water, treating contaminated water[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[1] |

| Frequency | 28 reported cases (2018)[1] |

In humans, the only known cause is Dracunculus medinensis.[3] The worm is about one to two millimeters wide, and an adult female is 60 to 100 centimeters long (males are much shorter at 12–29 mm or 0.47–1.14 in).[1][3] Outside humans, the young form can survive up to three weeks,[5] during which they must be eaten by water fleas to continue to develop.[1] The larva inside water fleas may survive up to four months.[5] Thus, for the disease to remain in an area, it must occur each year in humans.[6] A diagnosis of the disease can usually be made based on the signs and symptoms.[2]

Prevention is by early diagnosis of the disease followed by keeping the infected person from putting the wound in drinking water, thus decreasing the spread of the parasite.[1] Other efforts include improving access to clean water and otherwise filtering water if it is not clean.[1] Filtering through a cloth is often enough to remove the water fleas.[4] Contaminated drinking water may be treated with a chemical called temefos to kill the larva.[1] There is no medication or vaccine against the disease.[1] The worm may be slowly removed over a few weeks by rolling it over a stick.[3] The ulcers formed by the emerging worm may get infected by bacteria.[3] Pain may continue for months after the worm has been removed.[3]

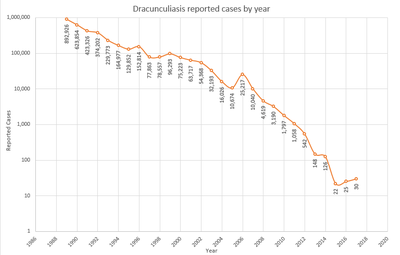

In 2019, 53 cases were reported across 4 countries.[7] This is down from an estimated 3.5 million cases in 1986.[3] In 2016 the disease occurred in three countries, all in Africa, down from 20 countries in the 1980s.[1][8] It will likely be the first parasitic disease to be globally eradicated.[9] Guinea worm disease has been known since ancient times.[3] The method of removing the worm is described in the Egyptian medical Ebers Papyrus, dating from 1550 BC.[10] The name dracunculiasis is derived from the Latin "affliction with little dragons",[11] while the name "guinea worm" appeared after Europeans saw the disease on the Guinea coast of West Africa in the 17th century.[10] Other Dracunculus species are known to infect various mammals, but do not appear to infect humans.[12][13] Dracunculiasis is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[14] Because dogs may also become infected,[15] the eradication program is monitoring and treating dogs as well.[16]

Signs and symptoms

Dracunculiasis is diagnosed by seeing the worms emerging from the lesions on the legs of infected individuals and by microscopic examinations of the larvae.[17]

As the worm moves downwards, usually to the lower leg, through the subcutaneous tissues, it leads to intense pain localized to its path of travel. The burning sensation experienced by infected people has led to the disease being called "the fiery serpent". Other symptoms include fever, nausea, and vomiting.[18] Female worms cause allergic reactions during blister formation as they migrate to the skin, causing an intense burning pain. Such allergic reactions produce rashes, nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, and localized edema. When the blister bursts, allergic reactions subside, but skin ulcers form, through which the worm can protrude. Only when the worm is removed is healing complete. Death of adult worms in joints can lead to arthritis and paralysis in the spinal cord.[19]

The pain caused by the worm's emergence—which typically occurs during planting and harvesting seasons—prevents many people from working or attending school for as long as three months. In heavily burdened agricultural villages fewer people are able to tend their fields or livestock, resulting in food shortages and lower earnings.[9][20] A study in southeastern Nigeria, for example, found that rice farmers in a small area lost US$20 million in just one year due to outbreaks of Guinea worm disease.[9]

Cause

Dracunculiasis is caused by drinking water contaminated by water fleas that host the Dracunculiasis medinensis larvae.[18] Dracunculiasis has a history of being very common in some of the world's poorest areas, particularly those with limited or no access to clean water.[21] In these areas, stagnant water sources may still host copepods, which can carry the larvae of the guinea worm.

After ingestion, the copepods die and are digested, thus releasing the stage 3 larvae, which then penetrate the host's stomach or intestinal wall, and then enter into the abdominal cavity and retroperitoneal space. After maturation, which takes approximately three months, mating takes place; the male worm dies after mating and is absorbed by the host's body.

Approximately one year after mating, the fertilized females migrate in the subcutaneous tissues adjacent to long bones or joints of the extremities.[10] They then move towards the surface, resulting in blisters on the skin, generally on the foot. Within 72 hours, the blister ruptures, exposing one end of the emergent worm. The blister causes a very painful burning sensation as the worm emerges, and the sufferer will often immerse the affected limb in water to relieve the burning sensation. When a blister or open sore is submerged in water, the adult female releases hundreds of thousands of stage 1 guinea worm larvae, thereby contaminating the water.

During the next few days, the female worm can release more larvae whenever it comes in contact with water, as it extends its posterior end through the hole in the host's skin. These larvae are eaten by copepods, and after two weeks (and two molts), the stage 3 larvae become infectious and, if not filtered from drinking water, will cause the cycle to repeat. Infected copepods can live in the water for up to four months.

The male guinea worm is typically much smaller (12–29 mm or 0.47–1.14 in) than the female, which, as an adult, can grow to 60–100 cm (2–3 ft) long and be as thick as a spaghetti noodle.[10][21]

Infection does not create immunity, so people can repeatedly experience Dracunculiasis throughout their lives.[21] Several worms may emerge simultaneously; the average is 1.8. Up to 14 worms have been reported in one individual.[3]

In drier areas just south of the Sahara desert, cases of the disease often emerge during the rainy season, which for many agricultural communities is also the planting or harvesting season. Elsewhere, the emerging worms are more prevalent during the dry season, when ponds and lakes are smaller and copepods are thus more concentrated in them. Guinea worm disease outbreaks can cause serious disruption to local food supplies and school attendance.[21]

The infection can be acquired by eating a fish paratenic host, but this is rare. No reservoir hosts are known; that is, each generation of worms must pass through a human—or possibly a dog.[19][22]

Hosts

Until recently humans and water fleas (Cyclops) were regarded as the only animals this parasite infects. It has been shown that baboons, cats, dogs, frogs and catfish (Synodontis) can also be infected naturally. Ferrets have been infected experimentally.[23]

Prevention

Guinea worm disease can be transmitted only by drinking contaminated water, and can be completely prevented through two relatively simple measures:[18]

- Prevent people from drinking contaminated water containing the Cyclops copepod (water flea), which can be seen in clear water as swimming white specks.

- Drink water drawn only from sources free from contamination.

- Filter all drinking water, using a fine-mesh cloth filter, to remove the guinea worm-containing crustaceans. Regular cotton cloth folded over a few times is an effective filter. A portable plastic drinking straw containing a nylon filter has proven popular.[24]

- Filter the water through ceramic or sand filters.

- Boil the water.

- Develop new sources of drinking water without the parasites, or repair dysfunctional water sources.

- Treat water sources with larvicides to kill the water fleas.[25]

- Prevent people with emerging Guinea worms from entering water sources used for drinking.

- Community-level case detection and containment is key. For this, staff must go door to door looking for cases, and the population must be willing to help and not hide their cases.

- Immerse emerging worms in buckets of water to reduce the number of larvae in those worms, and then discard that water on dry ground.

- Discourage all members of the community from setting foot in the drinking water source.

- Guard local water sources to prevent people with emerging worms from entering.

Treatment

There is no vaccine or medicine to treat or prevent Guinea worm disease.[18] Untreated cases can lead to secondary infections, disability and amputations.[24] Once a Guinea worm begins emerging, the first step is to do a controlled submersion of the affected area in a bucket of water. This causes the worm to discharge many of its larvae, making it less infectious. The water is then discarded on the ground far away from any water source. Submersion results in subjective relief of the burning sensation and makes subsequent extraction of the worm easier. To extract the worm, a person must wrap the live worm around a piece of gauze or a stick. The process may take several weeks.[3] Gently massaging the area around the blister can help loosen the worm.[9] This is nearly the same treatment that is noted in the famous ancient Egyptian medical text, the Ebers papyrus from c. 1550 BC.[10] Some people have said that extracting a Guinea worm feels like the afflicted area is on fire.[26][27] However, if the infection is identified before an ulcer forms, the worm can also be surgically removed by a trained doctor in a medical facility.[21]

Although Guinea worm disease is usually not fatal, the wound where the worm emerges could develop a secondary bacterial infection such as tetanus, which may be life-threatening—a concern in endemic areas where there is typically limited or no access to health care.[28] Analgesics can be used to help reduce swelling and pain and antibiotic ointments can help prevent secondary infections at the wound site.[21] At least in the Northern region of Ghana, the Guinea worm team found that antibiotic ointment on the wound site caused the wound to heal too well and too quickly making it more difficult to extract the worm and more likely that pulling would break the worm. The local team preferred to use something called "Tamale oil" (after the regional capital) which lubricated the worm and aided its extraction.

It is of great importance not to break the worm when pulling it out. Broken worms have a tendency to putrefy or petrify. Putrefaction leads to the skin sloughing off around the worm. Petrification is a problem if the worm is in a joint or wrapped around a vein or other important area.

Use of metronidazole or thiabendazole may make extraction easier, but also may lead to migration of the worm to other parts of the body.[29]

Epidemiology

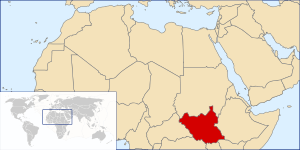

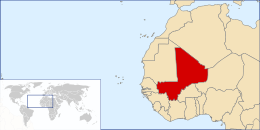

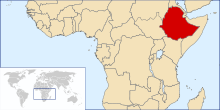

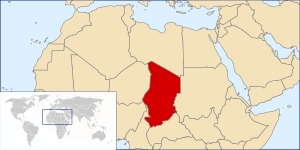

By 1986, there were an estimated 3.5 million cases of Guinea worm in 20 endemic nations in Asia and Africa,[9] with a relatively small number of cases reported occasionally in central and South America, although these were short-lived local transmissions that had originated in Africa. In December 1996, Cuba was certified free of the disease. By 1997 and 1998 further countries in the Americas were similarly certified, including Barbados, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Jamaica and Mexico.[30] Worldwide, in 2017 the number of cases had been reduced by more than 99.999% to 30 occurrences in four remaining countries in Africa: South Sudan, Chad, Mali and Ethiopia.[31]

Endemic countries must document the absence of indigenous cases of Guinea worm disease for at least three consecutive years to be certified as Guinea worm-free.[32] The results of this certification scheme have been remarkable: by 2017, 15 formerly endemic countries—Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Cote d'lvoire, Ghana, India, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Senegal, Togo, Uganda and Yemen—were certified to have eradicated the disease.[33]

Current situation

In 2017, 30 human cases were reported — 15 in Chad and 15 in Ethiopia; 13 of which were fully contained. For the first time ever, South Sudan reported no human infections for a whole calendar year: the last reported case was on 20 November 2016. No human cases were reported in Mali for the second year in a row.[34] In addition to their human cases, Chad reported 817 infected dogs and 13 infected domestic cats, and Ethiopia reported 11 infected dogs and 4 infected baboons. Despite no human infections, Mali reported 9 infected dogs and 1 infected cat.[34]

By May 2018, only three human cases had been reported worldwide. All three were in Chad according to The Carter Center.[35]

According to WHO, as of 31 October 2018, that number had increased to 21 human cases in 18 villages (8 villages in Chad, 9 in South Sudan and one in Angola). Over 1000 infected dogs were reported from Chad (1001), Ethiopia (11) and Mali (16) compared with 748 infected dogs for the same period in 2017. The increase in number does not necessarily mean that there are more infections - detection in animals only recently started and was likely under-reported.

There was evidence of re-emergence in Ethiopia (2008) and in Chad (2010) where transmission re-occurred after the country reported zero cases for almost 10 years.[36]

Endemic countries

At the end of 2015, South Sudan, Mali, Ethiopia and Chad still had endemic transmissions. For many years the major focus was South Sudan (independent after 2011, formerly the southern region of Sudan), which reported 76% of all cases in 2013.[31] In 2017 only Chad and Ethiopia had cases.[37]

| Date | South Sudan | Mali | Ethiopia | Chad | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||

| 2011 | 1,028[38] | 12[38] | 8[38] | 10[38] | 1058 |

| 2012 | 521[38] | 7[38] | 4[38] | 10[38] | 542 |

| 2013 | 113[38] | 11[38] | 7[38] | 14[38] | 148 (including 3 exported to Sudan) |

| 2014 | 70[38] | 40[38] | 3[38] | 13[38] | 126 |

| 2015 | 5[38] | 5[38] | 3[38] | 9[38] | 22 |

| 2016 | 6[38] | 0[38] | 3[38] | 16[38] | 25 |

| 2017 | 0[34] | 0[34] | 15[34] | 15[34] | 30 |

| 2018 | 10[39] | 0[39] | 0[39] | 17[39] | 28 (including one isolated case in Angola) |

| 2019 | 4[39] | 0[39] | 0[39] | 47[39] | 53 (including one isolated case in Angola and Cameroon) |

Eradication program

Since humans are the principal host for Guinea worm, and there is no evidence that D. medinensis has ever been reintroduced to humans in any formerly endemic country as the result of non-human infections, the disease can be controlled by identifying all cases and modifying human behavior to prevent it from recurring.[9][41] Over the years, the eradication program has faced several challenges:

- Inadequate security in some endemic countries

- Lack of political will from the leaders of some of the countries in which the disease is endemic

- The need for change in behaviour in the absence of a magic bullet treatment like a vaccine or medication

- Inadequate funding at certain times[11]

- The newly recognised transmission of guinea worm through non-human hosts (both domestic and wild animals)

History

Dracunculiasis has been a recognized disease for thousands of years:

- Guinea worm has been found in calcified Egyptian mummies.[9]

- An Old Testament description of "fiery serpents" may have been referring to Guinea worm: "And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died." (Numbers 21:4–9).[10]

- In the 2nd century BC, the Greek writer Agatharchides described this affliction as being endemic amongst certain nomads in what is now Sudan and along the Red Sea.[42][10]

- In the 18th century, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus identified D. medinensis in merchants who traded along the Gulf of Guinea (West African Coast).

- Guinea worms were described by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr as "[burrowing] into the naked feet of West-Indian slaves..."[43]

It has been suggested that the Rod of Asclepius (a symbol that represents medical practice) represents a Guinea worm wrapped around a stick for extraction.[44] According to this thinking, physicians might have advertised this common service by posting a sign depicting a worm on a rod. However plausible, there is no concrete evidence in support of this notion.

The Russian scientist Alexei Pavlovich Fedchenko (1844–1873) during the 1860s while living in Samarkand was provided with a number of specimens of the worm by a local doctor which he kept in water. While examining the worms Fedchenko noted the presence of water fleas with embryos of the guinea worm within them.[45]

In modern times, the first to describe dracunculiasis and its pathogenesis was the Bulgarian physician Hristo Stambolski, during his exile in Yemen (1877–1878).[46] He correctly inferred that the cause was infected water which people were drinking.

Etymology

Dracunculiasis once plagued a wide band of tropical countries in Africa and Asia. Its Latin name, Dracunculus medinensis ("little dragon from Medina"), derives from its one-time high incidence in the city of Medina (in modern Saudi Arabia), and its common name, Guinea worm, is due to a similar past high incidence along the Guinea coast of West Africa;[10] Guinea worm is no longer endemic in either location.[47]

Other animals

In March 2016, the World Health Organization convened a scientific conference to study the emergence of cases of infections of dogs. The worms are genetically indistinguishable from the Dracunculus medinensis that infects humans. The first case was reported in Chad in 2012; in 2016, there were more than 1,000 cases of dogs with emerging worms in Chad, 14 in Ethiopia, and 11 in Mali.[48] It is unclear if dog and human infections are related. It is possible that dogs may spread the disease to people, that a third organism may be able to spread it to both dogs and people, or that this may be a different type of Dracunculus. The current (as of 2014) epidemiological pattern of human infections in Chad appears different, with no sign of clustering of cases around a particular village or water source, and a lower average number of worms per individual.[49]

References

- "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease) Fact sheet N°359 (Revised)". World Health Organization. March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Cook, Gordon (2009). Manson's tropical diseases (22nd ed.). Edinburgh: Saunders. p. 1506. ISBN 9781416044703. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Greenaway, C (February 17, 2004). "Dracunculiasis (guinea worm disease)". CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (4): 495–500. PMC 332717. PMID 14970098.

- Cairncross, S; Tayeh, A; Korkor, AS (June 2012). "Why is dracunculiasis eradication taking so long?". Trends in Parasitology. 28 (6): 225–230. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.03.003. PMID 22520367.

- Junghanss, Jeremy Farrar, Peter J. Hotez, Thomas (2013). Manson's tropical diseases (23rd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier/Saunders. p. e62. ISBN 9780702053061. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- "Parasites – Dracunculiasis (also known as Guinea Worm Disease) Eradication Program". CDC. November 22, 2013. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- "View Latest Worldwide Guinea Worm Case Totals". www.cartercenter.org. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "Guinea Worm Cases Left in the World". Carter Center. Jan 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Guinea Worm Eradication Program". Carter Center. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Tropical Medicine Central Resource. "Dracunculiasis". Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. Archived from the original on 2008-12-29. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Barry M (June 2007). "The tail end of guinea worm — global eradication without a drug or a vaccine". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (25): 2561–2564. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078089. PMID 17582064.

- Junghanss, Jeremy Farrar, Peter J. Hotez, Thomas (2013). Manson's tropical diseases (23rd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 763. ISBN 9780702053061. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- "North American Guinea Worm". Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. June 6, 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and, Prevention (25 October 2013). "Progress toward global eradication of dracunculiasis—January 2012 – June 2013". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 62 (42): 829–833. PMC 4585614. PMID 24153313.

- WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis, CDC (March 25, 2016). "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #239" (PDF). Carter Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Z. Harrat; R. Halimi (2009). "La dracunculose d'importation : quatre cas confirmés dans le sud algérien" [Imported dracunculiasis: four cases confirmed in the south of Algeria] (PDF). Bulletin de la Société de pathologie exotique (in French). 102 (2): 119–122. doi:10.3185/pathexo3352 (inactive 2020-07-30). PMID 19583036. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-05-14.

- "Dracunculiasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2010-07-17. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- G. D. Schmidt; L S. Roberts (2009). Larry S. Roberts; John Janovy, Jr. (eds.). Foundations of Parasitology (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 480–484. ISBN 978-0-07-128458-5.

- Hopkins DR; Ruiz-Tiben E; Downs P; Withers PC Jr.; Maguire JH (2005-10-01). "Dracunculiasis Eradication: The Final Inch". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 73 (4): 669–675. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.669. PMID 16222007.

- "Fact Sheet:Dracunculiasis—Guinea Worm Disease". CDC. 2008-07-15. Archived from the original on 2010-04-27. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Chad holds annual review; focal distribution of dog infections" (PDF). 17 February 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- "Tug of War". Slate. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Hopkins, D.; Richards Jr, F.; Ruiz-Tiben, E.; Emerson, P.; Withers Jr, P. (2008). "Dracunculiasis, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, and trachoma". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1136 (1): 45–52. Bibcode:2008NYASA1136...45H. doi:10.1196/annals.1425.015. PMID 17954680.

- "World moves closer to eradicating ancient worm disease". World Health Organization. 2007-03-27. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- McNeil, DG (2006-03-26). "Dose of Tenacity Wears Down a Horrific Disease". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2008-12-10. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (December 1993). "Recommendations of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication". MMWR Recomm Rep. 42 (RR–16): 1–38. PMID 8145708. Archived from the original on 2007-05-09.

- Dracunculiasis: Treatment & Medication~treatment at eMedicine

- Watts S (2000). "Dracunculiasis in the Caribbean and South America:A Contribution to the History of Dracunculiasis Eradication". Med Hist. 44 (2): 227–250. doi:10.1017/s0025727300066412. PMC 1044253. PMID 10829425.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-06-03. Retrieved 2014-06-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- CDC (2000-10-11). "Progress Toward Global Dracunculiasis Eradication, June 2000". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 49 (32): 731–735. PMID 11411827.

- The Carter Center. "Activities by Country—Guinea Worm Eradication Program". The Carter Center. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-up #252" (PDF). The Carter Center. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- "Guinea Worm Disease (Dracunculiasis) Worldwide Case Numbers" (PDF). The Carter Center. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- Donald G. McNeil Jr. (22 March 2018). "South Sudan Halts Spread of Crippling Guinea Worms". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- "Guinea Worm Disease: Case Countdown". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2014-01-21.

- "Guinea Worm Disease: Case Countdown". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-19.

- "Number of Reported Cases of Guinea Worm Disease by Year: 1989–2017*" (PDF). Guinea Worm Eradication Program. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- Bimi, L.; Freeman, A. R.; Eberhard, M. L.; Ruiz-Tiben, E.; Pieniazek, N. J. (10 May 2005). "Differentiating Dracunculus medinensis from D. insignis, by the sequence analysis of the 18S rRNA gene" (PDF). Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 99 (5): 511–517. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.603.9521. doi:10.1179/136485905x51355. PMID 16004710. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Plutarch; Goodwin, William W., ed. (1871). "Symposiacs, Book VIII, Question 9, §. 3". Plutarch's Morals. vol. 3. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Little, Brown, and Co. p. 430.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) From p. 430: "Those that fell sick about the Red Sea, if we believe Agatharcides, besides other strange and unheard diseases, had little serpents in their legs and arms, which did eat their way out, but when touched shrunk in again, and raised intolerable inflammations in the muscles; … "

- Holmes, Oliver Wendell (1952). The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table (1858). London: J.M Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 180. ISBN 1406813176.

- Emerson, John (27 July 2003). "Eradicating Guinea Worm Disease". Social Design Notes. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- See:

- Fedchenko (Федченко), Alexei (Алексей) (1870). "О строении и размножении ришты (Filaria medinensis L.)" [On the structure and reproduction of the Guinea worm (Filaria medinensis L.)]. Известия Императорского Общества Любителей Естествознания, Антропологии и Этнографии [News of the Imperial Society of Devotees of Natural Science, Anthropology and Ethnography (Moscow)] (in Russian). 8 (1): 71–82.

- English translation: Fedchenko, A. P. (1971). "Concerning the structure and reproduction of the guinea-worm (Filaria medinensis L.)". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 20 (4): 511–523. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1971.20.511.

- Христо Стамболски: Автобиография, дневници и mспомени. (Autobiography of Hristo Stambolski. Sofia : Dŭržavna pečatnica, 1927–1931)

- "Guinea Worm Infection (Dracunculiasis)". The Imaging of Tropical Diseases. International Society of Radiology. 2008. Archived from the original on November 29, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". WHO. January 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Eberhard, ML; Ruiz-Tiben, E; Hopkins, DR; Farrell, C; Toe, F; Weiss, A; Withers PC, Jr; Jenks, MH; Thiele, EA; Cotton, JA; Hance, Z; Holroyd, N; Cama, VA; Tahir, MA; Mounda, T (January 2014). "The peculiar epidemiology of dracunculiasis in Chad". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 90 (1): 61–70. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0554. PMC 3886430. PMID 24277785.

External links

- "Guinea Worm Disease Eradication Program". Carter Center.

- Nicholas D. Kristof from the New York Times follows a young Sudanese boy with a Guinea Worm parasite infection who is quarantined for treatment as part of the Carter program

- Tropical Medicine Central Resource: "Guinea Worm Infection (Dracunculiasis)"

- World Health Organization on Dracunculiasis

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |