Poverty reduction

Poverty reduction, or poverty alleviation, is a set of measures, both economic and humanitarian, that are intended to permanently lift people out of poverty.

Measures, like those promoted by Henry George in his economics classic Progress and Poverty, are those that raise, or are intended to raise, ways of enabling the poor to create wealth for themselves as a means of ending poverty forever. In modern times, various economists within the Georgism movement propose measures like the land value tax to enhance access to the natural world for all. Poverty occurs in both developing countries and developed countries. While poverty is much more widespread in developing countries, both types of countries undertake poverty reduction measures.

Poverty has been historically accepted in some parts of the world as inevitable as non-industrialized economies produced very little, while populations grew almost as fast, making wealth scarce.[1] Geoffrey Parker wrote that

In Antwerp and Lyon, two of the largest cities in western Europe, by 1600 three-quarters of the total population were too poor to pay taxes, and therefore likely to need relief in times of crisis.[2]

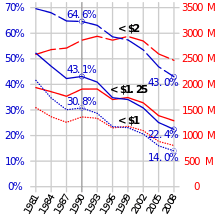

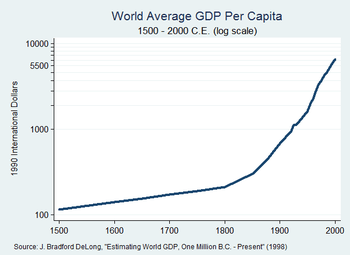

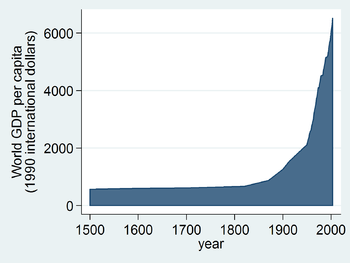

Poverty reduction occurs largely as a result of overall economic growth.[3][4] Food shortages were common before modern agricultural technology and in places that lack them today, such as nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation methods.[5][6] The dawn of the Industrial Revolution led to high economic growth, eliminating mass poverty in what is now considered the developed world.[3] World GDP per person quintupled during the 20th century.[7] In 1820, 75% of humanity lived on less than a dollar a day, while in 2001 only about 20% did.[3]

Today, continued economic development is constrained by the lack of economic freedoms. Economic liberalization requires extending property rights to the poor, especially to land.[8] Financial services, notably savings, can be made accessible to the poor through technology, such as mobile banking.[9][10] Inefficient institutions, corruption, and political instability can also discourage investment. Aid and government support in health, education, and infrastructure helps growth by increasing human and physical capital.[4]

Poverty alleviation also involves improving the living conditions of people who are already poor. Aid, particularly in the medical and scientific areas, is essential in providing better lives, such as the Green Revolution and the eradication of smallpox.[11][12] Problems with today's development aid include the high proportion of tied aid, which mandates receiving nations to buy products, often more expensive, originating only from donor countries.[13] Nevertheless, some believe (Peter Singer in his book The Life You Can Save) that small changes in the ways people in affluent nations lives their lives could solve world poverty.

Economic liberalization

Some commentators have claimed that, due to economic liberalization, poverty in the world is rising rather than declining,[14] and the data provided by the World Bank, which shows poverty is decreasing, is flawed.[15][16][17] They also argue that extending property rights protection to the poor is one of the most important poverty reduction strategies a nation can implement.[3] Securing property rights to land, the largest asset for most societies, is vital to their economic freedom.[3][11] The World Bank concludes that increasing land rights is 'the key to reducing poverty' citing that land rights greatly increase poor people's wealth, in some cases doubling it.[8] It is estimated that state recognition of the property of the poor would give them assets worth 40 times all the foreign aid since 1945.[3] Although approaches varied, the World Bank said the key issues were security of tenure and ensuring land transactions were low cost.[8] In China and India, noted reductions in poverty in recent decades have occurred mostly as a result of the abandonment of collective farming in China and the cutting of government red tape in India.[18]

New enterprises and foreign investment can be driven away by the results of inefficient institutions, corruption, the weak rule of law and excessive bureaucratic burdens.[3][4] It takes two days, two bureaucratic procedures, and $280 to open a business in Canada while an entrepreneur in Bolivia must pay $2,696 in fees, wait 82 business days, and go through 20 procedures to do the same.[3] Such costly barriers favor big firms at the expense of small enterprises where most jobs are created.[3] In India before economic reforms, businesses had to bribe government officials even for routine activities, which was in effect a tax on business.[4]

However, ending government sponsorship of social programs is sometimes advocated as a free market principle with tragic consequences. For example, the World Bank presses poor nations to eliminate subsidies for fertilizer that many farmers cannot afford at market prices. The reconfiguration of public financing in former Soviet states during their transition to a market economy called for reduced spending on health and education, sharply increasing poverty.[19][20][21][22]

Trade liberalization increases total surplus of trading nations. Remittances sent to poor countries, such as India, are sometimes larger than foreign direct investment and total remittances are more than double aid flows from OECD countries.[23] Foreign investment and export industries helped fuel the economic expansion of fast growing Asian nations.[24] However, trade rules are often unfair as they block access to richer nations' markets and ban poorer nations from supporting their industries.[19][25] Processed products from poorer nations, in contrast to raw materials, get vastly higher tariffs at richer nations' ports.[26] A University of Toronto study found the dropping of duty charges on thousands of products from African nations because of the African Growth and Opportunity Act was directly responsible for a "surprisingly large" increase in imports from Africa.[27] Deals can sometimes be negotiated to favor the developing country such as in China, where laws compel foreign multinationals to train their future Chinese competitors in strategic industries and render themselves redundant in the long term.[28] In Thailand, the 51 percent rule compels multinational corporations starting operations in Thailand give 51 percent control to a Thai company in a joint venture.[29]

Capital, infrastructure and technology

Long run economic growth per person is achieved through increases in capital (factors that increase productivity), both human and physical, and technology.[4] Improving human capital, in the form of health, is needed for economic growth. Nations do not necessarily need wealth to gain health.[30] For example, Sri Lanka had a maternal mortality rate of 2% in the 1930s, higher than any nation today.[31] It reduced it to 0.5–0.6% in the 1950s and to 0.06% today.[31] However, it was spending less each year on maternal health because it learned what worked and what did not.[31] Knowledge on the cost effectiveness of healthcare interventions can be elusive but educational measures to disseminate what works are available, such as the disease control priorities project. Promoting hand washing is one of the most cost effective health intervention and can cut deaths from the major childhood diseases of diarrhea and pneumonia by half.[32]

Human capital, in the form of education, is an even more important determinant of economic growth than physical capital.[4] Deworming children costs about 50 cents per child per year and reduces non-attendance from anemia, illness and malnutrition and is only a twenty-fifth as expensive to increase school attendance as by constructing schools.[33]

UN economists argue that good infrastructure, such as roads and information networks, helps market reforms to work.[34] China claims it is investing in railways, roads, ports and rural telephones in African countries as part of its formula for economic development.[34] It was the technology of the steam engine that originally began the dramatic decreases in poverty levels. Cell phone technology brings the market to poor or rural sections.[35] With necessary information, remote farmers can produce specific crops to sell to the buyers that brings the best price.[36]

Such technology also helps bring economic freedom by making financial services accessible to the poor. Those in poverty place overwhelming importance on having a safe place to save money, much more so than receiving loans.[9] Also, a large part of microfinance loans are spent on products that would usually be paid by a checking or savings account.[9] Mobile banking addresses the problem of the heavy regulation and costly maintenance of saving accounts.[9] Mobile financial services in the developing world, ahead of the developed world in this respect, could be worth $5 billion by 2012.[37] Safaricom's M-Pesa launched one of the first systems where a network of agents of mostly shopkeepers, instead of bank branches, would take deposits in cash and translate these onto a virtual account on customers' phones. Cash transfers can be done between phones and issued back in cash with a small commission, making remittances safer.[10]

However, several academic studies have shown that mobile phones have only limited effect on poverty reduction when not accompanied by other basic infrastructure development.[38]

Employment and productivity

Economic growth has the indirect potential to alleviate poverty, as a result of simultaneous increases in employment opportunities and labour productivity.[39] A study by researchers at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) of 24 countries that experienced growth found that in 18 cases, poverty was alleviated.[39] However, employment is no guarantee of escaping poverty, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that as many as 40% of workers are poor, not earning enough to keep their families above the $2 a day poverty line.[39] For instance, in India most of the chronically poor are wage earners in formal employment, because their jobs are insecure and low paid and offer no chance to accumulate wealth to avoid risks.[39] This appears to be the result of a negative relationship between employment creation and increased productivity, when a simultaneous positive increase is required to reduced poverty. According to the UNRISD, increasing labour productivity appears to have a negative impact on job creation: in the 1960s, a 1% increase in output per worker was associated with a reduction in employment growth of 0.07%, by the first decade of this century the same productivity increase implies reduced employment growth by 0.54%.[39]

Increases in employment without increases in productivity leads to a rise in the number of "working poor", which is why some experts are now promoting the creation of "quality" and not "quantity" in labour market policies.[39] This approach does highlight how higher productivity has helped reduce poverty in East Asia, but the negative impact is beginning to show.[39] In Vietnam, for example, employment growth has slowed while productivity growth has continued.[39] Furthermore, productivity increases do not always lead to increased wages, as can be seen in the US, where the gap between productivity and wages has been rising since the 1980s.[39] The ODI study showed that other sectors were just as important in reducing unemployment, as manufacturing.[39] The services sector is most effective at translating productivity growth into employment growth. Agriculture provides a safety net for jobs and economic buffer when other sectors are struggling.[39] This study suggests a more nuanced understanding of economic growth and quality of life and poverty alleviation.

Helping farmers

Raising farm incomes is described as the core of the antipoverty effort as three-quarters of the poor today are farmers.[40] Estimates show that growth in the agricultural productivity of small farmers is, on average, at least twice as effective in benefiting the poorest half of a country's population as growth generated in nonagricultural sectors.[41] For example, a 2012 study suggested that new varieties of chickpea could benefit Ethiopian farmers in future. The study assessed the potential economic and poverty impact of 11 improved chickpea varieties, released by the national agricultural research organization of Ethiopia in collaboration with the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, (ICRISAT). The researchers estimated that using the varieties would bring about a total benefit of US$111 million for 30 years with consumers receiving 39% of the benefit and producers 61%. They expected the generated benefit would lift more than 0.7 million people (both producers and consumers) out of poverty. The authors concluded that further investments in the chickpea and other legume research in Ethiopia were therefore justified as a means of poverty alleviation.[42]

Improving water management is an effective way to help reduce poverty among farmers. With better water management, they can improve productivity and potentially move beyond subsistence-level farming. During the Green Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, for example, irrigation was a key factor in unlocking Asia's agricultural potential and reducing poverty. Between 1961 and 2002, the irrigated area almost doubled, as governments sought to achieve food security, improve public welfare and generate economic growth. In South Asia, cereal production rose by 137% from 1970 to 2007. This was achieved with only 3% more land.[43]

The International Water Management Institute in Colombo, Sri Lanka aims to improve the management of land and water resources for food, livelihoods and the environment. One project its scientists worked on demonstrates the impact that improving water management in agriculture can have. The study, funded by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation, initially upgraded and irrigated the irrigation system on the Walawe Left Bank, Sri Lanka, in 1997. In 2005, irrigation was extended to a further area. An analysis of the whole area was carried out in 2007 and 2008. This study found that access to irrigation provided families with opportunities to diversify their livelihood activities and potentially increase their incomes. For example, people with land could reliably grow rice or vegetables instead of working as labourers or relying on rainfall to water their crops. Those without land could benefit by working within new inland fisheries. Within the project's control area, 57% of households were below the poverty line in 2002 compared with 43% in 2007.[44]

Building opportunities for self-sufficiency

Making employment opportunities available is just as important as increasing income and access to basic needs. Poverty activist Paul Polak has based his career around doing both at once, creating companies that employ the poor while creating "radically" affordable goods. In his book Out of Poverty he argues that traditional poverty eradication strategies have been misguided and fail to address underlying problems. He lists "Three Great Poverty Eradication Myths": that we can donate people out of poverty, that national economic growth will end poverty, and that Big Business, operating as it does now, will end poverty.[45] Economic models which lead to national growth and more big business will not necessarily lead to more opportunities for self-sufficiency. However, businesses designed with a social goal in mind, such as micro finance banks, may be able to make a difference.[46]

Growth vs. state intervention: comparative perspective in China, India, Brazil

A 2012 World Bank research article, "A Comparative Perspective on Poverty Reduction in Brazil, China, and India," looked at the three nations' strategies and their relative challenges and successes. During their reform periods, all three have reduced their poverty rates, but through a different mix of approaches. The report used a common poverty line of $1.25 per person, per day, at purchasing parity power for consumption in 2008. Using that metric and evaluating the period between 1981 and 2005, the poverty rate in China dropped from 84% to 16%; India from 60% to 42%; and Brazil from 17% to 8%. The report sketches an overall scorecard of the countries on the two basic dimensions of pro-poor growth and pro-poor policy intervention: "China clearly scores well on the pro-poor growth side of the card, but neither Brazil nor India do; in Brazil's case for lack of growth and in India's case for lack of poverty-reducing growth. Brazil scores well on the social policies side, but China and India do not; in China's case progress has been slow in implementing new social policies more relevant to the new market economy (despite historical advantages in this area, inherited from the past regime) and in India's case the bigger problems are the extent of capture of the many existing policies by non-poor groups and the weak capabilities of the state for delivering better basic public services."[47]

Aid

Welfare

Aid in its simplest form is a basic income grant, a form of social security periodically providing citizens with money. In pilot projects in Namibia, where such a program pays just $13 a month, people were able to pay tuition fees, raising the proportion of children going to school by 92%, child malnutrition rates fell from 42% to 10% and economic activity grew 10%.[48][49] Aid could also be rewarded based on doing certain requirements. Conditional Cash Transfers, widely credited as a successful anti-poverty program, is based on actions such as enrolling children in school or receiving vaccinations.[50] In Mexico, for example, the country with the largest such program, dropout rates of 16- to 19-year-olds in rural area dropped by 20% and children gained half an inch in height.[51] Initial fears that the program would encourage families to stay at home rather than work to collect benefits have proven to be unfounded. Instead, there is less excuse for neglectful behavior as, for example, children are prevented from begging on the streets instead of going to school because it could result in suspension from the program.[51]

Welfare states have an effect on poverty reduction. Currently modern, expansive welfare states that ensure economic opportunity, independence and security in a near universal manner are still the exclusive domain of the developed nations.[52] commonly constituting at least 20% of GDP, with the largest Scandinavian welfare states constituting over 40% of GDP.[53] These modern welfare states, which largely arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, seeing their greatest expansion in the mid 20th century, and have proven themselves highly effective in reducing relative as well as absolute poverty in all analyzed high-income OECD countries.[54][55][56]

Philosopher Thomas Pogge is a supporter of gathering funds for the poor by using a sort of Global Resources Dividend.

Development aid

A major proportion of aid from donor nations is 'tied', mandating that a receiving nation buy products originating only from the donor country.[13] This can be harmful economically.[13] For example, Eritrea is forced to spend aid money on foreign goods and services to build a network of railways even though it is cheaper to use local expertise and resources.[13] Money from the United States to fight AIDS requires it be spent on U.S brand name drugs that can cost up to $15,000 a year compared to $350 a year for generics from other countries.[13] Only Norway, Denmark, Netherlands and Britain have stopped tying their aid.[13]

Some people disagree with aid when looking at where the development aid money from NGOs and other funding is going. Funding tends to be used in a selective manner where the highest ranked health problem is the only thing treated, rather than funding basic health care development. This can occur due to a foundation's underlying political aspects to their development plan, where the politics outweigh the science of disease. The diseases then treated are ranked by their prevalence, morbidity, risk of mortality, and the feasibility of control.[57] Through this ranking system, the disease that cause the most mortality and are most easily treated are given the funding. The argument occurs because once these people are treated, they are sent back to the conditions that led to the disease in the first place. By doing this, money and resources from aid can be wasted when people are re-infected. This was seen in the Rockefeller Foundation's Hookworm campaign in Mexico in the 1920s, where people were treated for hookworm and then contracted the disease again once back in the conditions from which they came. To prevent this, money could be spent on teaching citizens of the developing countries health education, basic sanitation, and providing adequate access to prevention methods and medical infrastructure. Not only would NGO money be better spent, but it would be more sustainable. These arguments suggest that the NGO development aid should be used for prevention and determining root causes rather acting upon political endeavours and treating for the sake of saying they helped.[58]

Some think tanks and NGOs have argued that Western monetary aid often only serves to increase poverty and social inequality, either because it is conditioned with the implementation of harmful economic policies in the recipient countries,[59] or because it is tied to the importing of products from the donor country over cheaper alternatives.[13] Sometimes foreign aid is seen to be serving the interests of the donor more than the recipient,[60] and critics also argue that some of the foreign aid is stolen by corrupt governments and officials, and that higher aid levels erode the quality of governance. Policy becomes much more oriented toward what will get more aid money than it does towards meeting the needs of the people.[61] Problems with the aid system and not aid itself are that the aid is excessively directed towards the salaries of consultants from donor countries, the aid is not spread properly, neglecting vital, less publicized area such as agriculture, and the aid is not properly coordinated among donors, leading to a plethora of disconnected projects rather than unified strategies.[12]

Supporters of aid argue that these problems may be solved with better auditing of how the aid is used.[61] Immunization campaigns for children, such as against polio, diphtheria and measles have saved millions of lives.[12] Aid from non-governmental organizations may be more effective than governmental aid; this may be because it is better at reaching the poor and better controlled at the grassroots level.[61] As a point of comparison, the annual world military spending is over $1 trillion.[62]

Debt relief

One of the proposed ways to help poor countries that emerged during the 1980s has been debt relief. Given that many less developed nations have gotten themselves into extensive debt to banks and governments from the rich nations, and given that the interest payments on these debts are often more than a country can generate per year in profits from exports, cancelling part or all of these debts may allow poor nations "to get out of the hole".[63] If poor countries do not have to spend so much on debt payments, they can use the money instead for priorities which help reduce poverty such as basic health-care and education.[64] Many nations began offering services, such as free health care even while overwhelming the health care infrastructure, because of savings that resulted from the rounds of debt relief in 2005.[65]

The role of education and skillbuilding as precursors to economic development

Universal public education has some role in preparing youth for basic academic skills and perhaps many trade skills, as well. Apprenticeships clearly build needed trade skills. If modest amounts of cash and land can be combined with a modicum of agricultural skills in a temperate climate, subsistence can give way toward modest societal wealth. As has been mentioned, education for women will allow for reduced family size—an important poverty reduction event in its own right. While all components mentioned above are necessary, the portion of education pertaining to the variety of skills needed to build and maintain the infrastructure of a developing (moving out of poverty) society: building trades; plumbing; electrician; well-drilling; farm and transport mechanical skills (and others) are clearly needed in large numbers of individuals, if the society is to move out of poverty or subsistence. Yet, many well-developed western economies are moving strongly away from the essential apprenticeships and skill training which affords a clear vocational path out of modern urban poverty.

Microloans

One of the most popular of the new technical tools for economic development and poverty reduction are microloans made famous in 1976 by the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. The idea is to loan small amounts of money to farmers or villages so these people can obtain the things they need to increase their economic rewards. A small pump costing only $50 could make a very big difference in a village without the means of irrigation. A specific example is the Thai government's People's Bank which is making loans of $100 to $300 to help farmers buy equipment or seeds, help street vendors acquire an inventory to sell, or help others set up small shops. The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) Vietnam country programme supports operations in 11 poor provinces. Between 2002 and 2010 around 1,000 saving and credit groups (SCGs) were formed, with over 17,000 members; these SCGs increased their access to microcredit for taking up small-scale farm activities.[66]

Empowering women

The empowerment of women has relatively recently become a significant area of discussion with respect to development and economics; however it is often regarded as a topic that only addresses and primarily deals with gender inequality. Because women and men experience poverty differently, they hold dissimilar poverty reduction priorities and are affected differently by development interventions and poverty reduction strategies.[67] In response to the socialized phenomenon known as the feminization of poverty, policies aimed to reduce poverty have begun to address poor women separately from poor men.[67] In addition to engendering poverty and poverty interventions, a correlation between greater gender equality and greater poverty reduction and economic growth has been illustrated by research through the World Bank, suggesting that promoting gender equality through empowerment of women is a qualitatively significant poverty reduction strategy.[68]

Gender equality

Addressing gender equality and empowering women are necessary steps in overcoming poverty and furthering development as supported by the human development and capabilities approach and the Millennium Development Goals.[69] Disparities in the areas of education, mortality rates, health and other social and economic indicators impose large costs on well-being and health of the poor, which diminishes productivity and the potential to reduce poverty.[67] The limited opportunities of women in most societies restrict their aptitude to improve economic conditions and access services to enhance their well-being.[67]

Mainstreaming gender

Gender mainstreaming, the concept of placing gender issues into the mainstream of society, was established by the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women as a global strategy for promoting gender equality; the UN conference emphasized the necessity to ensure that gender equality is a primary goal in all areas of social and economic development, which includes the discussion of poverty and its reduction.[70] Correspondingly, the World Bank also created objectives to address poverty with respect to the different effects on women.[71] One important goal was the revision of laws and administrative practices to ensure women's equal rights and access to economic resources.[71] Mainstreaming strengthens women's active involvement in poverty alleviation by linking women's capabilities and contributions with macro-economic issues.[71] The underlying purpose of both the UN and World Bank policies speaks to the use of discussion of gender issues in the promotion of gender equality and reduction of poverty.

Strategies to empower women

Several platforms have been adopted and reiterated across many organizations in support of the empowerment of women with the specific aim of reducing poverty. Encouraging more economic and political participation by women increases financial independence from and social investment in the government, both of which are critical to pulling society out of poverty.[72]

Economic participation

Women's economic empowerment, or ensuring that women and men have equal opportunities to generate and manage income, is an important step to enhancing their development within the household and in society.[73] Additionally, women play an important economic role in addressing poverty experienced by children.[73] By increasing female participation in the labor force, women are able to contribute more effectively to economic growth and income distribution since having a source of income elevates their financial and social status.[73] However, women's entry into the paid labor force does not necessarily equate to reduction of poverty; the creation of decent employment opportunities and movement of women from the informal work sector to the formal labor market are key to poverty reduction.[74] Other ways to encourage female participation in the workforce to promote decline of poverty include providing childcare services, increasing educational quality and opportunities, and furthering entrepreneurship for women.[73] Protection of property rights is a key element in economically empowering women and fostering economic growth overall for both genders. With legitimate claims to land, women gain bargaining power, which can be applied to their lives outside of and within the household.[75] The ability and opportunity for women to lawfully own land also decreases the asset gap that exists between women and men, which promotes gender equality.[73]

Political participation

Political participation is supported by organizations such as IFAD as one pillar of gender equality and women's empowerment.[76] Sustainable economic growth requires poor people to have influence on the decisions that affect their lives;[77] specifically strengthening women's voices in the political process builds social independence and greater consideration of gender issues in policy.[78] In order to promote women's political empowerment, the United Nations Development Programme advocated for several efforts: increase women in public office; strengthen advocate ability of women's organizations; ensure fair legal protection; and provide equivalent health and education.[79] Fair political representation and participation enable women to lobby for more female-specific poverty reduction policies and programs.

Good institutions

Efficient institutions that are not corrupt and obey the rule of law make and enforce good laws that provide security to property and businesses. Efficient and fair governments would work to invest in the long-term interests of the nation rather than plunder resources through corruption.[4] Researchers at UC Berkeley developed what they called a "Weberianness scale" which measures aspects of bureaucracies and governments which Max Weber described as most important for rational-legal and efficient government over 100 years ago. Comparative research has found that the scale is correlated with higher rates of economic development.[80] With their related concept of good governance World Bank researchers have found much the same: Data from 150 nations have shown several measures of good governance (such as accountability, effectiveness, rule of law, low corruption) to be related to higher rates of economic development.[81]

Funds from aid and natural resources are often diverted into private hands and then sent to banks overseas as a result of graft.[82] If Western banks rejected stolen money, says a report by Global Witness, ordinary people would benefit "in a way that aid flows will never achieve".[82] The report asked for more regulation of banks as they have proved capable of stanching the flow of funds linked to terrorism, money-laundering or tax evasion.[82]

Some, like Thomas Pogge, call for a global organization that can manage some form of Global Resources Dividend, which could evolve in complexity with time.

Examples of good governance leading to economic development and poverty reduction include Thailand, Taiwan, Malaysia, South Korea, and Vietnam, which tend to have a strong government, called a hard state or development state. These "hard states" have the will and authority to create and maintain policies that lead to long-term development that helps all their citizens, not just the wealthy. Multinational corporations are regulated so that they follow reasonable standards for pay and labor conditions, pay reasonable taxes to help develop the country, and keep some of the profits in the country, reinvesting them to provide further development.

The United Nations Development Program published a report in April 2000 which focused on good governance in poor countries as a key to economic development and overcoming the selfish interests of wealthy elites often behind state actions in developing nations. The report concludes that "Without good governance, reliance on trickle-down economic development and a host of other strategies will not work."[83] Despite the promise of such research several questions remain, such as where good governance comes from and how it can be achieved. The comparative analysis of one sociologist[84] suggests that broad historical forces have shaped the likelihood of good governance. Ancient civilizations with more developed government organization before colonialism, as well as elite responsibility, have helped create strong states with the means and efficiency to carry out development policies today. On the other hand, strong states are not always the form of political organization most conducive to economic development. Other historical factors, especially the experiences of colonialism for each country, have intervened to make a strong state and/or good governance less likely for some countries, especially in Africa. Another important factor that has been found to affect the quality of institutions and governance was the pattern of colonization (how it took place) and even the identity of colonizing power. International agencies may be able to promote good governance through various policies of intervention in developing nations as indicated in a few African countries, but comparative analysis suggests it may be much more difficult to achieve in most poor nations around the world.[84]

Other approaches

Another approach that has been proposed for alleviating poverty is Fair Trade which advocates the payment of an above market price as well as social and environmental standards in areas related to the production of goods. The efficacy of this approach to poverty reduction is controversial.

Community and monetary economist Thomas H. Greco, Jr. has argued that the mainstream global economy with its debt-based currency has built-in structural incentives that create poverty through keeping money scarce. Greco points to the success of modern barter clubs and historical local currencies such as the Wörgl Experiment at revitalizing stagnant local economies, and calls for the creation of community currency as a means to reduce or eliminate poverty.[85]

The Toronto Dollar is an example of a local currency oriented towards reducing poverty. Toronto Dollars are sold and redeemed in such a way that raise funds which are then given as grants to local charities, primarily ones oriented towards reducing poverty.[86] Toronto Dollars also provide a means to create an incentive for welfare recipients to work: Toronto dollars can be given as gifts to welfare recipients who perform volunteer work for charitable and non-profit organizations, and these gifts do not affect welfare benefits.[87]

Some have argued for radical economic change in the system. There are several fundamental proposals for restructuring existing economic relations, and many of their supporters argue that their ideas would reduce or even eliminate poverty entirely if they were implemented. Such proposals have been put forward by both left-wing and right-wing groups: socialism, communism, anarchism, libertarianism, binary economics and participatory economics, among others.

Inequality can be reduced by progressive tax.[88]

In law, there has been a move to establish the absence of poverty as a human right.[89][90]

The IMF and member countries have produced Poverty Reduction Strategy papers or PRSPs.[91]

In his book The End of Poverty,[92][93] prominent economist Jeffrey Sachs laid out a plan to eradicate global poverty by 2025. Following his recommendations, international organizations such as the Global Solidarity Network[94] are working to help eradicate poverty worldwide with intervention in the areas of housing, food, education, basic health, agricultural inputs, safe drinking water, transportation and communications.

The Poor People's Economic Human Rights Campaign is an organization in the United States working to secure freedom from poverty for all by organizing the poor themselves. The Campaign believes that a human rights framework, based on the value of inherent dignity and worth of all persons, offers the best means by which to organize for a political solution to poverty.

Climate change adaptation

The increase in extreme weather events, linked to climate change, and resulting disasters is expected to continue. Disasters are a major cause of impoverishment and can reverse progress towards poverty reduction.[95]

It is predicted that by 2030, 325 million (plus) extremely poor people will be living in the 49 most hazard prone countries. Most of these are located in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.[95]

A researcher at a leading global think-tank, the Overseas Development Institute, suggests that far more effort should be done to better coordinate and integrate poverty reduction strategies with climate change adaptation.[96] The two issues are argued to be currently only dealt with in parallel as most poverty reduction strategy papers ignore climate change adaptation altogether, while National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs) likewise do not deal directly with poverty reduction. Adaptation-poverty linkages were found to be strongest in NAPAs from sub-Saharan Africa LDCs.[96]

Bicycles

Experiments done in Africa (Uganda and Tanzania) and Sri Lanka on hundreds of households have shown that a bicycle can increase the income of a poor family by as much as 35%.[97][98][99] Transport, if analyzed for the cost-benefit analysis for rural poverty alleviation, has given one of the best returns in this regard. For example, road investments in India were a staggering 3–10 times more effective than almost all other investments and subsidies in rural economy in the decade of the 1990s. What a road does at a macro level to increase transport, the bicycle supports at the micro level. The bicycle, in that sense, can be one of the best means to eradicate poverty in poor nations.

Millennium Development Goals

Eradication of extreme poverty and hunger by 2015 is one of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). In addition to broader approaches, the Sachs Report (for the UN Millennium Project)[100] proposes a series of "quick wins", approaches identified by development experts which would cost relatively little but could have a major constructive effect on world poverty. The quick wins are:

- Access to information on sexual and reproductive health.

- Action against domestic violence.

- Appointing government scientific advisors in every country.

- Deworming school children in affected areas.

- Drugs for AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.

- Eliminating school fees.

- Ending user fees for basic health care in developing countries.

- Free school meals for schoolchildren.

- Legislation for women's rights, including rights to property.

- Planting trees.

- Providing soil nutrients to farmers in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Providing mosquito nets.

- Access to electricity, water and sanitation.

- Supporting breast-feeding.

- Training programs for community health in rural areas.

- Upgrading slums, and providing land for public housing.

Sustainable Development Goals

The first of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) calls for an end to poverty by 2030 and seeks to ensure social protection for the poor and supporting people affected by climate-related extreme events.[101] As the decade that began in 2002, the percentage of the world's population living under the poverty line by half, from 26 per cent to 13 per cent. If during those 10 years growth rates prevailed over the next 15 years, it is possible to decrease the rate of extreme poverty in the world to 4 per cent by 2030, assuming that growth will benefit all income groups of the population on an equal footing. However, if the growth rates over a longer period of 20 years, the rate of prevalent global poverty is likely to be about 6 per cent. In other words, the eradication of extreme poverty will require a significant change from its historical growth rates.

Poverty targeting

Poverty reduction requires governments to identify and reach out to extremely poor and help them out of poverty through sustainable measures. One such approach supported by many international donors is of targeted poverty reduction programmes.[102] There are several poverty targeting methods through which poor communities are identified and tracked for poverty reduction programmes. For instance, one common method of poverty targeting is 'means testing' that uses a certain income or expenditure threshold for an individual or the a household to be considered as poor and eligible for support.[103]

Global initiatives to end hunger and undernutrition

An important part of the fight against poverty are efforts to end hunger and achieve food security. In April 2012, the Food Assistance Convention was signed, the world's first legally binding international agreement on food aid. The May 2012 Copenhagen Consensus recommended that efforts to combat hunger and malnutrition should be the first priority for politicians and private sector philanthropists looking to maximize the effectiveness of aid spending. They put this ahead of other priorities, like the fight against malaria and AIDS.[104]

The main global policy to reduce hunger and poverty are the recently approved Sustainable Development Goals. In particular Goal 2: Zero Hunger sets globally agreed targets to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.[105]

In 2013 Caritas International started a Caritas-wide initiative aimed at ending systemic hunger by 2025. The One human family, food for all campaign focuses on awareness raising, improving the impact of Caritas programs and advocating the implementation of the right to food.[106]

The partnership Compact2025, led by IFPRI with the involvement of UN organisations, NGOs and private foundations[107] develops and disseminates evidence-based advice to politicians and other decision-makers aimed at ending hunger and undernutrition in the coming 10 years, by 2025.[108]

The EndingHunger campaign is an online communication campaign aimed at raising awareness of the hunger problem. It has many worked through viral videos depicting celebrities voicing their anger about the large number of hungry people in the world.

Another initiative focused on improving the hunger situation by improving nutrition is the Scaling up Nutrition movement (SUN). Started in 2010, this movement of people from governments, civil society, the United Nations, donors, businesses and researchers publishes a yearly progress report on the changes in their 57 partner countries.[109]

Poverty reduction in Taiwan

In spite of the intensive reduction strategies deployed in the previous two decades, poverty levels in several countries of the world has not been reduced.[110] Recent research has demonstrated that the low wage levels of the needy families have risen gradually, although in some scenarios they have declined.[111] While wage level is the main median pointer of welfare, such results suggest that past poverty reduction procedures have not been precise. Unless suitable reduction procedures are formulated and implemented in the near future, rustic poverty will probably be a real issue for quite some long time. Families are determined to be low-pay if their monthly income does not surpass the evaluated monthly minimum set by every city or region. To meet the family's essential needs (shelter, food, clothing, and education) in Taipei, one would need to have $337 every month. This sum changes relying upon the city's way of life; for instance, one would just need to have $171 every month to live in Kinmen County.[112]

Sustained economic growth is noted as the main propelling agent for Poverty Reduction in Taiwan.[113] While internal FDI has no noteworthy effect on the mean wage of poor people, outward FDI from Taiwan in the previous two decades appears to have adversely affected the poorest 20% of the populace. Poverty in Taiwan has nearly been eliminated, with under 1 percent of the populace considered as poor or earning the low-level pay. This implies more than 99 percent of the populace appreciates the advantages of Taiwan's economic flourishing and extraordinarily enhanced personal satisfaction.[114] Beside lowly-paid families, the government offers support to other individuals, for example, the elderly and the incapacitated, who cannot work. During 1980 to 1999 Taiwanese government developed a program called National Health Insurance program. NHI mainly provides economically disadvantaged people with quality healthcare at an affordable price.[115] July 1993, the government of Taiwan started giving a monthly sponsorship to elderly people. People beyond 65 years old whose normal family salary is not exactly, or equivalent to, 1.5 times the base monthly costs are fit to get a monthly sponsorship of $174.[112] Private transfers also play an important role in Taiwan for antipoverty according to the date Taiwan provided to the Luxembourg Income Studies, the results indicates the private transfer has greater impact than public transfers in terms of proving welfare state.[116]

In 1999, the government of Taiwan spent US$5.08 billion on social welfare projects and offered numerous sorts of assistance to people and families from low-pay sets.[114] Notwithstanding money, assistance to get employment is given to the breadwinners in families, alongside educational guide for school-age children and well-being programs for women and children. In addition, there are additionally community associations, scholastic organizations, and private establishments arranged by government offices to help needy people. In principle, Taiwan is currently a liberal and elections based society. Hence social versatility ought to be the standard.[112] Notably, as per an investigation of extra cash in Taiwan by the Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, families with the most astounding dispensable salaries number 2.6 people, while families with the least discretionary cash flow number 4.7 people.[112] With rising costs of simple commodities and privatization of the training market, economically distraught families will end up in an undeniably hard position to educate their own children. However, this type of social welfare will significantly lower the Taiwan's revenue. Due to the slow economic development in the past years, this method will no longer close the income inequality or reduce the unemployment rate effectively in the future.[117]

See also

|

|

References

- "Under traditional (i.e., non-industrialized) modes of economic production, widespread poverty had been accepted as inevitable. The total output of goods and services, even if equally distributed, would still have been insufficient to give the entire population a right to an adequate standard of living by prevailing standards. With the economic productivity that resulted from industrialization, however, this ceased to be the case" Encyclopædia Britannica, "Poverty"

- Geoffrey Parker (2001). "Europe in crisis, 1598–1648". Wiley–Blackwell. p. 11. ISBN 0-631-22028-3

- "Ending Mass Poverty" by Ian Vásquez, Cato Institute, 4 September 2001

- Krugman, Paul, and Robin Wells. Macroeconomics. 2. New York City: Worth Publishers, 2009. Print.

- Easterbrook, Gregg (1 January 1997). "Forgotten Benefactor of Humanity". The Atlantic. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Ethical Man blog: Is the green movement part of the problem?". BCC.

- Angus Maddison, see graph

- "Business – Land rights 'help fight poverty'". BBC News.

- Kiviat, Barbara (30 August 2009). "Next Step for Microfinance: Taking Deposits". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Africa's mobile banking revolution". 12 August 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- EDT, Fareed Zakaria (19 September 2008). "Zakaria: How to Spread Democracy". Newsweek. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Science/Nature – Why aid does work". BBC News.

- "News and Views from the Global South". Inter Press Service. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010.

- "Global inequality may be much worse than we think", The Guardian, 8 April 2016

- Edward, Peter (2006). "The Ethical Poverty Line: a moral quantification of absolute poverty" (PDF). Third World Quarterly. 27 (2): 377–393. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2016.

- "World bank poverty figures: what do they mean?". Share The World's Resources (STWR).

- Shaikh, Anwar. "Globalization and the Myth of free Trade" (PDF). Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Can aid bring an end to poverty?". BBC News: Africa.

- Dugger, Celia W. (2 December 2007). "Ending Famine, Simply by Ignoring the Experts" – via NYTimes.com.

- Transition: The First Ten Years – Analysis and Lessons for Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, The World Bank, Washington, DC, 2002, p. 4.

- "Study Finds Poverty Deepening in Former Communist Countries". New York Times. 12 October 2000.

- Child poverty soars in eastern Europe". BBC News. 11 October 2000.

- "The aid workers who really help". The Economist. 8 October 2009.

- Vogel, Ezra F. 1991. The Four Little Dragons: The Spread of Industrialization in East Asia. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- "Market access". Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- admin (10 October 2006). "Make Trade Fair". Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- "News". University of Toronto.

- Lorenz, Andreas; Wagner, Wieland (27 February 2007). "Red China, Inc.: Does Communism Work After All?". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Muscat, Robert J. 1994. The Fifth Tiger: A Study of Thai Development. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- "Disease Control Priorities Project". Archived from the original on 6 April 2006. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Brown, David (3 April 2006). "Saving Millions for Just a Few Dollars" – via washingtonpost.com.

- "Millions mark UN hand-washing day". 15 October 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (20 November 2009). "How Can We Help the World's Poor?" – via NYTimes.com.

- "Home". BBC News.

- Crilly, Rob (4 June 2008). "UN aid debate: Give cash, not food?" – via The Christian Science Monitor.

- Baldauf, Scott (23 February 2007). "Market approach recasts often-hungry Ethiopia as potential bread basket" – via The Christian Science Monitor.

- "Africa pioneers mobile bank push". 15 June 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Matous, Petr (30 March 2017). "Mobile phones are not always a cure for poverty in remote regions". The Conversation.

- Claire Melamed, Renate Hartwig and Ursula Grant 2011. Jobs, growth and poverty: what do we know, what don't we know, what should we know? London: Overseas Development Institute

- Dugger, Celia W. (20 October 2007). "World Bank report puts agriculture at core of antipoverty effort". nytimes.com. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- "Climate Change: Bangladesh facing the challenge". The World Bank. 8 September 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Macharia I, Orr A, Simtowe F and Asfaw, S., Potential economic and poverty impact of improved chickpea technologies in Ethiopia http://exploreit.icrisat.org/page/chickpea/685/107. ICRISAT. Downloaded 26 January 2014.

- Mukherji, A. Revitalising Asia's Irrigation: To sustainably meet tomorrow's food needs 2009, IWMI and FAO

- Water, poverty and equity. Water Issue Brief, Issue 8, 2010.

- Polak, Paul. "Out of Poverty".

- Simanowitz, Anton. "Ensuring Impact: Reaching the Poorest While Building Financially Self-Sufficient Institutions, and Showing Improvement in the Lives of the Poorest Families" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "Comparative Perspective on Poverty Reduction in Brazil, China, and India". Journalist's Resource.org.

- Krahe, Dialika (10 August 2009). "A New Approach to Aid: How a Basic Income Program Saved a Namibian Village". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Namibians line up for free cash". 23 May 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Brazil becomes antipoverty showcase".

- Bridges, Tyler (21 September 2009). "Latin America makes a dent in poverty with 'conditional cash' programs" – via The Christian Science Monitor.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Barr, N. (2004). The economics of the welfare state. New York: Oxford University Press (USA).

- Kenworthy, L (1999). "Do social-welfare policies reduce poverty? A cross-national assessment" (PDF). Social Forces. 77 (3): 1119–39. doi:10.1093/sf/77.3.1119.

- Bradley, D.; Huber, E.; Moller, S.; Nielson, F.; Stephens, J. D. (2003). "Determinants of relative poverty in advanced capitalist democracies". American Sociological Review. 68 (3): 22–51. doi:10.2307/3088901. JSTOR 3088901.

- Smeeding, T (2005). "Public policy, economic inequality, and poverty: The United States in comparative perspective". Social Science Quarterly. 86: 955–83. doi:10.1111/j.0038-4941.2005.00331.x.

- Walsh, Julia A.; Kenneth S. Warren (1980). "Selective primary health care: An interim strategy for disease control in developing countries". Social Science & Medicine. Part C: Medical Economics. 14 (2): 146. doi:10.1016/0160-7995(80)90034-9. PMID 7403901.

- Birn, Anne-Emanuelle; Armando Solórzano (1999). "Public health policy paradoxes: science and politics in the Rockefeller Foundation's hookworm campaign in Mexico in the 1920s". Social Science & Medicine. 49 (9): 1209. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00160-4. PMID 10501641.

- Haiti's rice farmers and poultry growers have suffered greatly since trade barriers were lowered in 1994. Archived 18 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine By Jane Regan

- US and Foreign Aid, GlobalIssues.org

- "Will More Foreign Aid End Global Poverty?". ABC News. 15 November 2007.

- "SIPRI Yearbook 2006". Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "World Bank Group - International Development, Poverty, & Sustainability". World Bank. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Q&A: African debt relief". 11 June 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Zambia overwhelmed by free health care". BBC NEWS – Africa.

- RIDP, PCR and Validation, 2010.

- Zuckerman, Elaine. 2002 "Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers and Gender". Berlin, Germany: Conference on Sustainable Poverty Reduction and PRSPs.

- World Bank. 2001a "Engendering Development: Through Gender Equality in Rights, Resources, and Voice". Policy Research Report. Oxford University Press.

- U.N. General Assembly, 55th Session. "United Nations Millennium Declaration." (A/55/L.2). 8 September 2000.

- "Definition of Gender Mainstreaming". International Labour Organization.

- Muwanigwa, Virginia. 2002. "Gender Considerations in Poverty Alleviation". Harere, Zimbabwe.

- Narayan, Deepa and Nicholas Stern. 2002. "Empowerment and Poverty Reduction: A Sourcebook", pp. 1–272. Washington DC: World Bank.

- UNICEF. 2007. "Equality in Employment," in The State of the World's Children, pp. 36–49. New York: UNICEF.

- Chen, Martha, Joann Vanek, Francie Lund, James Heintz with Renana Jhabvala, and Christine Bonner. 2005. "Employment, Gender, and Poverty," in Progress of the World's Women, pp. 36–57. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women.

- Agarwal, Bina. 1994. "Land Rights for Women: Making the Case," in A Field of One's Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia, pp. 1–50. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- "Strategy and Approach: Gender equality and women's empowerment". International Labour Organization. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- "Occupational Health and Safety. [Social Impact]. ICP. Inclusive Cities Project (2008-2014)". SIOR, Social imapct Open Repository. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017.

- IFAD. 2007. "Strategy and Approach: Gender equality and women's empowerment". 21 Mar. 2011. <http://www.ifad.org/gender/approach/index.htm Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine>.

- "Democratic Governance". UNDP. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014.

- Evans, Peter; Rauch, James E. (1999). "Bureaucracy and Growth: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects of 'Weberian' State Structures on Economic Growth". American Sociological Review. 64 (5): 748–65. doi:10.2307/2657374. JSTOR 2657374.

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A; Zoido-Lobaton, P. "Governance Matters.". World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 2196. Washington DC.

- "Dancing with despots". The Economist. 12 March 2009.

- United Nations Development Report. 2000. Overcoming Human Poverty: UNDP Poverty Report 2000. New York: United Nations Publications.

- Kerbo, Harold (2005). World Poverty: The Roots of Global Inequality and the Modern World System. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780073042954.

- Thomas Greco, Jr., Money Understanding and Creating Alternatives to Legal Tender, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2001. ISBN 978-1-890132-37-8.

- Barbara Turnbull, "Milestone for the `Toronto Dollar'", Toronto Star, 22 Mar. 2008.

- Mark Herpel, "The Toronto Dollar: Community Alternative Dollar", California Chronicle, 18 Apr. 2008. Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Six policies to reduce economic inequality". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Thomas Pogge. "Poverty and Human Rights" (PDF). Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Poverty and Human Rights". Amnesty International. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP)

- "The End of Poverty". Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- The End of Poverty by JEFFREY D. SACHS for time.com

- "Global Solidarity Network". Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Andrew Shepherd, Tom Mitchell, Kirsty Lewis, Amanda Lenhardt, Lindsey Jones, Lucy Scott and Robert Muir-Wood (2013) "The geography of poverty, disasters and climate extremes in 2030" London: Overseas Development Institute

- Martin Prowse, Natasha Grist and Cheikh Sourang (2009) "Closing the gap between climate adaptation and poverty reduction frameworks" London: Overseas Development Institute

- "Bicycle: The Unnoticed Potential". BicyclePotential.org. 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Niklas Sieber (1998). "Appropriate Transportation and Rural Development in Makete District, Tanzania" (PDF). Journal of Transport Geography. 6 (1): 69–73. doi:10.1016/S0966-6923(97)00040-9. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "Project Tsunami Report Confirms The Power of Bicycle" (PDF). World Bicycle Relief. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "UN Millennium Project – Publications".

- "Goal 1 .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- James G. Bennett (10 October 2018). "Costs and benefits of poverty targeting". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- James G. Bennett (11 October 2018). "Six main methodologies". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "Outcome". Copenhagen Consensus Center.

- "Hunger and food security". United Nations Sustainable Development.

- "Pope Francis denounces 'global scandal' of hunger". 9 December 2013.

- "Leadership Council".

- "Compact2025: Ending hunger and undernutrition". IFPRI.

- "SUN communication materials".

- Chinn, Dennis (1979). "The University of Chicago Press Journals". Rural Poverty and the Structure of Farm Household Income in Developing Countries: Evidence from Taiwan. 27 (2): 283–301. doi:10.1086/451093. JSTOR 1153441.

- Rajamann. "Poverty inequality and economic growth: Rural Punjab". Journal of Development Studies. 11.

- "Taiwan – Poverty and wealth". Nations Encyclopedia. 2 November 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Tsai, Pang-Long; Huang, Chao-Hsi (2007). "Openness, Growth and Poverty: The Case of Taiwan". World Development. 35 (11): 1858–71. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.11.013.

- "Handbook of the Nations , 17th,18th, 19th and 20theditions for 1996, 1997, 1998 and 1999 data". CIA World Factbook 2001 [Online] for 2000 Data.

- "Universal Health Coverage in Taiwan". National Health Insurance Administration. National Health Insurance Administration. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- Kim, Jin Wook. "Private Transfers and Emerging Welfare States in East Asia: A Comparative Perspective" (PDF). Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- "The Development of Social Welfare Policy in Taiwan: Welfare Debates between the Left and the Right". National Policy Foundation. National Policy Foundation. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

Further reading

- Klein, Martin H. (2008). Poverty Alleviation through Sustainable Strategic Business Models. p. 295. ISBN 978-90-5892-168-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poverty reduction. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Poverty reduction |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Information and Communication Technologies for Poverty Alleviation |

- United Nations Rule of Law: Poverty Reduction, on the relationship between poverty reduction, the rule of law and the United Nations.

- The Life You Can Save – Acting Now to End World Poverty

- "Educate a Woman, You Educate a Nation" – South Africa Aims to Improve its Education for Girls WNN – Women News Network. 28 August 2007. Lys Anzia

- Information and Communication Technologies for Development and Poverty Reduction: The Potential of Telecommunications Edited by Maximo Torero and Joachim von Braun (2006), Johns Hopkins University Press

- Highly-Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) debt relief: Lessons from IMF-World Bank work, 2001–2005, Bill Dorotinsky, IMF/FAD