Living Planet Index

The Living Planet Index (LPI) is an indicator of the state of global biological diversity, based on trends in vertebrate populations of species from around the world. The Zoological Society of London (ZSL) manages the index in cooperation with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) a.k.a. the World Wildlife Federation.

As of 2018, the index is statistically created from journal studies, online databases and government reports for 16,704 populations of 4,005 species of mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian and fish,[1] or approximately six percent of the world's vertebrate species.[2]

Results

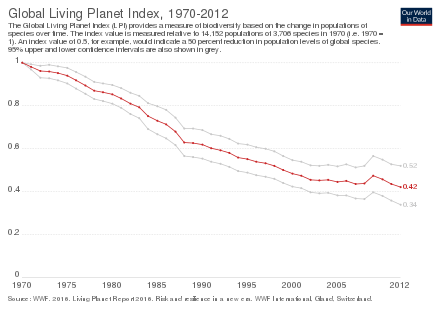

From 1970 to 2000, the population of measured species declined on average by 38%.[3] Between 1970 and 2012 the index fell by 58%. This global trend suggests that natural ecosystems are degrading at a rate unprecedented in human history.[4] As of 2018, the vertebrate populations have declined by 60% over the past 44 years.[5] Since 1970, freshwater species have declined 83%, and tropical populations in South and Central America declined 89%.[5] The authors note that, "An average trend in population change is not an average of total numbers of animals lost."[1]

Calculation

As of 2014, the Living Planet Database (LPD) is maintained by ZSL, and contains more than 20,000 population trends for more than 4,200 species of fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.[6]

The global LPI is calculated using over 14,000 of these population time-series which are gathered from a variety of sources such as journals, online databases and government reports.

A generalized additive modelling framework is used to determine the underlying trend in each population time-series. Average rates of change are calculated and aggregated to the species level.[7][8]

Each species trend is aggregated to produce an index for the terrestrial, marine and freshwater systems. This process uses a weighted average method which places most weight on the largest (most species-rich) groups within a biogeographic realm. This is done to counteract the uneven spatial and taxonomic distribution of data in the LPD. The three system indices are then averaged to produce the global LPI.[9]

Criticism

The fact that "all decreases in population size, regardless of whether they bring a population close to extinction, are equally accounted for" has been noted as a limitation.[10]

In 2005, WWF authors identified that the population data was potentially unrepresentative.[3] As of 2009, the database was found to contain too much bird data and gaps in the population coverage of tropical species, although it showed "little evidence of bias toward threatened species".[7] The 2016 report was criticized by a professor at Duke University for over-representing western Europe, where more data were available.[11] Talking to National Geographic, he criticised the attempt to combine data from different regions and ecosystems into a single figure, arguing that such reports are likely motivated by a desire to grab attention and raise money.[12]

A 2017 investigation of the index by members of the ZSL team published in PLOS One found higher declines than had been estimated, and indications that in areas where less data is available, species might be declining more quickly.[9]

Publication

The index was originally developed in 1997 by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in collaboration with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC), the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme.[3] WWF first published the index in 1998.[3] Since 2006, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) manages the index in cooperation with WWF.[13]

Results are presented biennially in the WWF Living Planet Report and in publications such as the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and the UN Global Biodiversity Outlook. National and regional reports are now being produced to focus on relevant issues at a smaller scale. The latest edition of the Living Planet Report was released in October 2018.[5]

Coverage

In 2018, National Geographic said that the report had been "widely misinterpreted" as suggesting "we['d] lost 60 percent of all animals over the course of 40 years".[14] Although they said the results were still "catastrophic", they explained that since the index measures biodiversity, it's weighted towards declines in species with smaller populations. Likewise, Ed Yong wrote in The Atlantic that the report was "widely mischaracterized—although the actual news is still grim".[2]

Convention on Biological Diversity

In April 2002, and again in 2006, at the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), 188 nations committed themselves to actions to: “… achieve, by 2010, a significant reduction of the current rate of biodiversity loss at the global, regional and national levels…”[15]

The LPI played a pivotal role in measuring progress towards the CBD's 2010 target.[16][17] It has also been adopted by the CBD as an indicator of progress towards its Nagoya Protocol 2011-2020 targets 5, 6, and 12 (part of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets).[18]

Informing the CBD 2020 strategic plan, the Indicators and Assessments Unit at ZSL is concerned with ensuring the most rigorous and robust methods are implemented for the measurement of population trends, expanding the coverage of the LPI to more broadly represent biodiversity, and disaggregating the index in meaningful ways (such as assessing the changes in exploited or invasive species).[19]

See also

Further reading

- Resnick, Brian (1 November 2018). "Animal populations have declined an astonishing 60 percent since 1970". Vox. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

References

- ZSL (30 October 2018). "Crunching numbers: the data behind the Living Planet Index". Zoological Society of London. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Yong, Ed (31 October 2018). "Wait, Have We Really Wiped Out 60 Percent of Animals?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Loh, Jonathan; et al. (2005). "The Living Planet Index: using species population time series to track trends in biodiversity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 360 (1454): 289–95. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1584. PMC 1569448. PMID 15814346.

- Report 2016: Risk and resilience in a new era (PDF) (Report). Living Planet. World Wildlife Fund. pp. 1–148. ISBN 978-2-940529-40-7. Retrieved 29 October 2016. (Summary Archived 13 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine).

- "WWF Report Reveals Staggering Extent of Human Impact on Planet" (Press release). World Wildlife Fund. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018. Report 2018: Aiming higher (PDF) (Report). Living Planet. World Wildlife Fund. pp. 1–75. ISBN 978-2-940529-90-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018. (Summary Archived 21 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine).

- "About the index". Zoological Society of London and WWF. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Collen, B. , Loh, J. , Whitmee, S. , McRae, L. , Amin, R. and Baillie, J. E. (2009). "Monitoring Change in Vertebrate Abundance: the Living Planet Index". Conservation Biology. 23 (2): 317–327. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01117.x. PMID 19040654.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Loh, J., Green, R.E., Ricketts, T., Lamoreux, J., Jenkins, M., Kapos, V., and Randers, J., 2005. The Living Planet Index: using species population time series to track trends in biodiversity. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 360: 289–295.

- McRae, Louise; Deinet, Stefanie; Freeman, Robin (3 January 2017). "The Diversity-Weighted Living Planet Index: Controlling for Taxonomic Bias in a Global Biodiversity Indicator". PLOS One. 12 (1): e0169156. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169156. PMC 5207715. PMID 28045977.

- Pereira, HM, Cooper, HD (2006). "Towards the global monitoring of biodiversity change" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 21 (3): 123–129. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.10.015. Retrieved 3 November 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "WWF report: Mass wildlife loss caused by human consumption". BBC News. 30 October 2018. and Morelle, Rebecca (27 October 2016). "World wildlife 'falls by 58% in 40 years'". BBC News. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Brian Clark Howard (27 October 2016). "World to Lose Two-Thirds of Wild Animals by 2020?". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- "Living Planet Index: Partners and Collaborators". Zoological Society of London and WWF. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Brown, Elizabeth Anne (1 November 2018). "Widely misinterpreted report still shows catastrophic animal decline". National Geographic. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- "Report of the Eighth Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity" (PDF). UNEP. 15 June 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Butchart, S. H. M., Walpole, M. et al. (2010) "Global Biodiversity: Indicators of Recent Declines." Science 328(5982): 1164-1168.

- UNEP (2006) Report on the eighth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity In: CBD, editor. pp. 374.

- "Aichi Biodiversity Targets". CBD Secretariat. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- "Indicators and Assessments Unit". Zoological Society of London. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

External links

- "Living Planet Index". Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and WWF. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- LPI at GitHub