Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness, is a disease caused by infection with the parasitic worm Onchocerca volvulus.[1] Symptoms include severe itching, bumps under the skin, and blindness.[1] It is the second-most common cause of blindness due to infection, after trachoma.[6]

| Onchocerciasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | River blindness, Robles disease |

| |

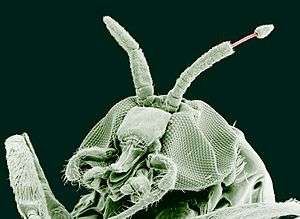

| An adult black fly with the parasite Onchocerca volvulus coming out of the insect's antenna, magnified 100x | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Itching, bumps under the skin, blindness[1] |

| Causes | Onchocerca volvulus spread by a black fly[1] |

| Prevention | Avoiding bites (insect repellent, proper clothing)[2] |

| Medication | Ivermectin, doxycycline[3][4] |

| Frequency | 15.5 million (2015)[5] |

The parasite worm is spread by the bites of a black fly of the Simulium type.[1] Usually, many bites are required before infection occurs.[7] These flies live near rivers, hence the common name of the disease.[6] Once inside a person, the worms create larvae that make their way out to the skin,[1] where they can infect the next black fly that bites the person.[1] There are a number of ways to make the diagnosis, including: placing a biopsy of the skin in normal saline and watching for the larva to come out, looking in the eye for larvae, and looking within the bumps under the skin for adult worms.[8]

A vaccine against the disease does not exist.[1] Prevention is by avoiding being bitten by flies.[2] This may include the use of insect repellent and proper clothing.[2] Other efforts include those to decrease the fly population by spraying insecticides.[1] Efforts to eradicate the disease by treating entire groups of people twice a year are ongoing in a number of areas of the world.[1] Treatment of those infected is with the medication ivermectin every six to twelve months.[1][3] This treatment kills the larvae but not the adult worms.[4] The antibiotic doxycycline weakens the worms by killing an associated bacterium called Wolbachia, and is recommended by some as well.[4] The lumps under the skin may also be removed by surgery.[3]

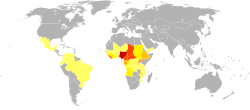

About 15.5 million people are infected with river blindness.[5] Approximately 0.8 million have some amount of loss of vision from the infection.[7][4] Most infections occur in sub-Saharan Africa, although cases have also been reported in Yemen and isolated areas of Central and South America.[1] In 1915, the physician Rodolfo Robles first linked the worm to eye disease.[9] It is listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a neglected tropical disease.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Adult worms remain in subcutaneous nodules, limiting access to the host's immune system.[11] Microfilariae, in contrast, are able to induce intense inflammatory responses, especially upon their death. Wolbachia species have been found to be endosymbionts of O. volvulus adults and microfilariae, and are thought to be the driving force behind most of O. volvulus morbidity. Dying microfilariae have been recently discovered to release Wolbachia surface protein that activates TLR2 and TLR4, triggering innate immune responses and producing the inflammation and its associated morbidity.[12] The severity of illness is directly proportional to the number of infected microfilariae and the power of the resultant inflammatory response.[13]

Skin involvement typically consists of intense itching, swelling, and inflammation.[14] A grading system has been developed to categorize the degree of skin involvement:[15][16][17]

- Acute papular onchodermatitis – scattered pruritic papules

- Chronic papular onchodermatitis – larger papules, resulting in hyperpigmentation

- Lichenified onchodermatitis – hyperpigmented papules and plaques, with edema, lymphadenopathy, pruritus and common secondary bacterial infections

- Skin atrophy – loss of elasticity, the skin resembles tissue paper, 'lizard skin' appearance

- Depigmentation – 'leopard skin' appearance, usually on anterior lower leg

- Glaucoma effect – eyes malfunction, begin to see shadows or nothing

Ocular involvement provides the common name associated with onchocerciasis, river blindness, and may involve any part of the eye from conjunctiva and cornea to uvea and posterior segment, including the retina and optic nerve.[14] The microfilariae migrate to the surface of the cornea. Punctate keratitis occurs in the infected area. This clears up as the inflammation subsides. However, if the infection is chronic, sclerosing keratitis can occur, making the affected area become opaque. Over time, the entire cornea may become opaque, thus leading to blindness. Some evidence suggests the effect on the cornea is caused by an immune response to bacteria present in the worms.[13]

The infected person's skin is itchy, with severe rashes permanently damaging patches of skin.

Mazzotti reaction

The Mazzotti reaction, first described in 1948, is a symptom complex seen in patients after undergoing treatment of onchocerciasis with the medication diethylcarbamazine (DEC). Mazzotti reactions can be life-threatening, and are characterized by fever, urticaria, swollen and tender lymph nodes, tachycardia, hypotension, arthralgias, oedema, and abdominal pain that occur within seven days of treatment of microfilariasis.

The phenomenon is so common when DEC is used that this drug is the basis of a skin patch test used to confirm that diagnosis. The drug patch is placed on the skin, and if the patient is infected with O. volvulus microfilaria, localized pruritus and urticaria are seen at the application site.[18]

Nodding disease

This is an unusual form of epidemic epilepsy associated with onchocerciasis although definitive link has not been established.[19] This syndrome was first described in Tanzania by Louise Jilek-Aall, a Norwegian psychiatric doctor in Tanzanian practice, during the 1960s. It occurs most commonly in Uganda and South Sudan. It manifests itself in previously healthy 5–15-year-old children, is often triggered by eating or low temperatures and is accompanied by cognitive impairment. Seizures occur frequently and may be difficult to control. The electroencephalogram is abnormal but cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are normal or show non-specific changes. If there are abnormalities on the MRI they are usually present in the hippocampus. Polymerase chain reaction testing of the CSF does not show the presence of the parasite.

Cause

The cause is Onchocerca volvulus.

Life cycle

The life of the parasite can be traced through the black fly and the human hosts in the following steps:[20][21]

- A Simulium female black fly takes a blood meal on an infected human host, and ingests microfilaria.

- The microfilaria enter the gut and thoracic flight muscles of the black fly, progressing into the first larval stage (J1.).

- The larvae mature into the second larval stage (J2.), and move to the proboscis and into the saliva in its third larval stage (J3.). Maturation takes about seven days.

- The black fly takes another blood meal, passing the larvae into the next human host’s blood.

- The larvae migrate to the subcutaneous tissue and undergo two more molts. They form nodules as they mature into adult worms over six to 12 months.

- After maturing, adult male worms mate with female worms in the subcutaneous tissue to produce between 700 and 1,500 microfilaria per day.

- The microfilaria migrate to the skin during the day, and the black flies only feed in the day, so the parasite is in a prime position for the female fly to ingest it. Black flies take blood meals to ingest these microfilaria to restart the cycle.

Diagnosis

Classification

Onchocerciasis causes different kinds of skin changes, which vary in different geographic regions; it may be divided into the following phases or types:[22]:440–441

- Erisipela de la costa

- An acute phase, it is characterized by swelling of the face, with erythema and itching.[22]:440 This skin change, erisípela de la costa, of acute onchocerciasis is most commonly seen among victims in Central and South America.[23]

- Mal morando

- This cutaneous condition is characterized by inflammation accompanied by hyperpigmentation.[22]:440

- Sowda

- A cutaneous condition, it is a localized type of onchocerciasis.[22]:440

Additionally, the various skin changes associated with onchocerciasis may be described as follows:[22]:440

- Leopard skin

- The spotted depigmentation of the skin that may occur with onchocerciasis[22]:440

- Elephant skin

- The thickening of human skin that may be associated with onchocerciasis[22]:440

- Lizard skin

- The thickened, wrinkled skin changes that may result with onchocerciasis[22]:441

Prevention

Various control programs aim to stop onchocerciasis from being a public health problem. The first was the Onchocerciasis Control Programme (OCP), which was launched in 1974, and at its peak, covered 30 million people in 11 countries. Through the use of larvicide spraying of fast-flowing rivers to control black fly populations, and from 1988 onwards, the use of ivermectin to treat infected people, the OCP eliminated onchocerciasis as a public health problem. The OCP, a joint effort of the World Health Organization, the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme, and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, was considered to be a success, and came to an end in 2002. Continued monitoring ensures onchocerciasis cannot reinvade the area of the OCP.[24]

In 1995, the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) began covering another 19 countries, mainly relying upon the use of the drug ivermectin. Its goal was to set up community-directed treatment with ivermectin for those at risk of infection. In these ways, transmission has declined.[25] APOC closed in 2015 and aspects of its work taken over by the WHO Expanded Special Programme for the Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases (ESPEN). As in the Americas, the objective of ESPEN working with Government Health Ministries and partner NGDOs, is the elimination of transmission of onchocerciasis. This requires consistent annual treatment of 80% of the population in endemic areas for at least 10–12 years - the life span of the adult worm. No African country has so far verified elimination of onchocerciasis, but treatment has stopped in some areas (e.g. Nigeria), following epidemiological and entomological assessments that indicated that no ongoing transmission could be detected. In 2015, WHO facilitated the launch of an elimination program in Yemen which was subsequently put on hold due to conflict.

In 1992, the Onchocerciasis Elimination Programme for the Americas, which also relies on ivermectin, was launched.[26] On July 29, 2013, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) announced that after 16 years of efforts, Colombia had become the first country in the world to eliminate onchocerciasis.[27] In September 2015, the Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas announced that onchocerciasis only remained in a remote region on the border of Brazil and Venezuela.[28][29] The area is home to the Yanomami indigenous people. The first countries to receive verification of elimination were Colombia in 2013, Ecuador in 2014, and Mexico in 2015.[30] Guatemala has submitted a request for verification. The key factor in elimination is mass administration of the antiparasitic drug ivermectin. The initial projection was that the disease would be eliminated from remaining foci in the Americas by 2012.[31]

No vaccine to prevent onchocerciasis infection in humans is available. A vaccine to prevent onchocerciasis infection for cattle is in phase three trials. Cattle injected with a modified and weakened form of O. ochengi larvae have developed very high levels of protection against infection. The findings suggest that it could be possible to develop a vaccine that protects people against river blindness using a similar approach. Unfortunately, a vaccine to protect humans is still many years off.[32][33]

Treatment

.jpg)

In mass drug administration (MDA) programmes, the treatment for onchocerciasis is ivermectin (trade name: Mectizan); infected people can be treated with two doses of ivermectin, six months apart, repeated every three years. The drug paralyses and kills the microfilariae causing fever, itching, and possibly oedema, arthritis and lymphadenopathy. Intense skin itching is eventually relieved, and the progression towards blindness is halted. In addition, while the drug does not kill the adult worms, it does prevent them for a limited time from producing additional offspring. The drug therefore prevents both morbidity and transmission for up to several months.

Ivermectin treatment is particularly effective because it only needs to be taken once or twice a year, needs no refrigeration, and has a wide margin of safety, with the result that it has been widely given by minimally trained community health workers.[34]

Antibiotics

For the treatment of individuals, doxycycline is used to kill the Wolbachia bacteria that live in adult worms. This adjunct therapy has been shown to significantly lower microfilarial loads in the host, and may kill the adult worms, due to the symbiotic relationship between Wolbachia and the worm.[35][36][37] In four separate trials over ten years with various dosing regimens of doxycycline for individualized treatment, doxycycline was found to be effective in sterilizing the female worms and reducing their numbers over a period of four to six weeks. Research on other antibiotics, such as rifampicin, has shown it to be effective in animal models at reducing Wolbachia both as an alternative and as an adjunct to doxycycline.[38] However, doxycycline treatment requires daily dosing for at least four to six weeks, making it more difficult to administer in the affected areas.[34]

Ivermectin

Ivermectin kills the parasite by interfering with the nervous system and muscle function, in particular, by enhancing inhibitory neurotransmission. The drug binds to and activates glutamate-gated chloride channels.[34] These channels, present in neurons and myocytes, are not invertebrate-specific, but are protected in vertebrates from the action of ivermectin by the blood–brain barrier.[34] Ivermectin is thought to irreversibly activate these channel receptors in the worm, eventually causing an inhibitory postsynaptic potential. The chance of a future action potential occurring in synapses between neurons decreases and the nematodes experience flaccid paralysis followed by death.[39][40][41]

Ivermectin is directly effective against the larval stage microfilariae of O. volvulus; they are paralyzed and can be killed by eosinophils and macrophages. It does not kill adult females (macrofilariae), but does cause them to cease releasing microfilariae, perhaps by paralyzing the reproductive tract.[34] Ivermectin is very effective in reducing microfilarial load and reducing number of punctate opacities in individuals with onchocerciasis.[42]

Moxidectin

Moxidectin was approved for onchocerciasis in 2018 for people over the age of 11 in the United States.[43] The safety of multiple doses is unclear.[43]

Epidemiology

About 21 million people were infected with this parasite in 2017; about 1.2 million of those had vision loss.[44] As of 2017, about 99% of onchocerciasis cases occurred in Africa.[44] Onchocerciasis is currently relatively common in 31 African countries, Yemen, and isolated regions of South America.[45] Over 85 million people live in endemic areas, and half of these reside in Nigeria. Another 120 million people are at risk for contracting the disease. Due to the vector’s breeding habitat, the disease is more severe along the major rivers in the northern and central areas of the continent, and severity declines in villages farther from rivers.[46] Onchocerciasis was eliminated in the northern focus in Chiapas, Mexico,[47] and the focus in Oaxaca, Mexico, where Onchocerca volvulus existed, was determined, after several years of treatment with ivermectin, as free of the transmission of the parasite.[48]

According to a 2002 WHO report, onchocerciasis has not caused a single death, but its global burden is 987,000 disability adjusted life years (DALYs). The severe pruritus alone accounts for 60% of the DALYs. Infection reduces the host’s immunity and resistance to other diseases, which results in an estimated reduction in life expectancy of 13 years.[45]

History

Onchocerca originated in Africa and was exported to the Americas by the slave trade, as part of the Columbian exchange that introduced other old world diseases such as yellow fever into the New World. Findings of a phylogenetic study in the mid-90s are consistent with an introduction to the New World in this manner. DNA sequences of savannah and rainforest strains in Africa differ, while American strains are identical to savannah strains in western Africa.[49] The microfilarial parasite that causes the disease was first identified in 1874 by an Irish naval surgeon, John O’Neill, who was seeking to identify the cause of a common skin disease along the west coast of Africa, known as “craw-craw”.[50] Rudolf Leuckart, a German zoologist, later examined specimens of the same filarial worm sent from Africa by a German missionary doctor in 1890 and named the organism Filaria volvulus.[51]

Rodolfo Robles and Rafael Pacheco in Guatemala first mentioned the ocular form of the disease in the Americas about 1915. They described a tropical worm infection with adult Onchocerca that included inflammation of the skin, especially the face (‘erisipela de la costa’), and eyes.[52] The disease, commonly called the “filarial blinding disease”, and later referred to as “Robles disease”, was common among coffee plantation workers. Manifestations included subcutaneous nodules, anterior eye lesions, and dermatitis. Robles sent specimens to Émile Brumpt, a French parasitologist, who named it O. caecutiens in 1919, indicating the parasite caused blindness (Latin “caecus” meaning blind).[53] The disease was also reported as being common in Mexico.[54] By the early 1920s, it was generally agreed that the filaria in Africa and Central America were morphologically indistinguishable and the same as that described by O’Neill 50 years earlier.

Robles hypothesized that the vector of the disease was the day-biting black fly, Simulium. Scottish physician Donald Blacklock of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine confirmed this mode of transmission in studies in Sierra Leone. Blacklock’s experiments included the re-infection of Simulium flies exposed to portions of the skin of infected subjects on which nodules were present, which led to elucidation of the life cycle of the Onchocerca parasite.[55] Blacklock and others could find no evidence of eye disease in Africa. Jean Hissette, a Belgian ophthalmologist, discovered in 1930 that the organism was the cause of a “river blindness” in the Belgian Congo.[56] Some of the patients reported seeing tangled threads or worms in their vision, which were microfilariae moving freely in the aqueous humor of the anterior chamber of the eye.[57] Blacklock and Strong had thought the African worm did not affect the eyes, but Hissette reported that 50% of patients with onchocerciasis near the Sankuru river in the Belgian Congo had eye disease and 20% were blind. Hisette Isolated the microfilariae from an enucleated eye and described the typical chorioretinal scarring, later called the “Hissette-Ridley fundus” after another ophthalmologist, Harold Ridley, who also made extensive observations on onchocerciasis patients in north west Ghana, publishing his findings in 1945.[58] Ridley first postulated that the disease was brought by the slave trade. The international scientific community was initially skeptical of Hisette’s findings, but they were confirmed by the Harvard African Expedition of 1934, led by Richard P. Strong, an American physician of tropical medicine.[59]

Society and culture

Since 1987, ivermectin has been provided free of charge for use in humans by Merck through the Mectizan donation program (MDP). The MDP works together with ministries of health and nongovernmental development organisations, such as the World Health Organization, to provide free ivermectin to those who need it in endemic areas.[60]

In 2015 William C. Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura were co-awarded half of that year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of the avermectin family of compounds, the forerunner of ivermectin. The latter has come to decrease the occurrence of lymphatic filariasis and onchoceriasis.[61]

Uganda's government, working with the Carter Center river blindness program since 1996, switched strategies for distribution of Mectizan. The male-dominated volunteer distribution system had failed to take advantage of traditional kinship structures and roles. The program switched in 2014 from village health teams to community distributors, primarily selecting women with the goal of assuring that everyone in the circle of their family and friends received river blindness information and Mectizan.[62]

Research

Animal models for the disease are somewhat limited, as the parasite only lives in primates, but there are close parallels. Litomosoides sigmodontis , which will naturally infect cotton rats, has been found to fully develop in BALB/c mice. Onchocerca ochengi, the closest relative of O. volvulus, lives in intradermal cavities in cattle, and is also spread by black flies. Both systems are useful, but not exact, animal models.[63]

A study of 2501 people in Ghana showed the prevalence rate doubled between 2000 and 2005 despite treatment, suggesting the parasite is developing resistance to the drug.[38][64][65] A clinical trial of another antiparasitic agent, moxidectin (manufactured by Wyeth), began on July 1, 2009 (NCT00790998).[66]

A Cochrane review compared outcomes of people treated with ivermectin alone versus doxycycline plus ivermectin. While there were no differences in most vision-related outcomes between the two treatments, there was low quality evidence suggesting treatment with doxycycline plus ivermectine showed improvement in iridocyclitis and punctate keratitis, over those treated with ivermectine alone.[67]

See also

- Carter Center River Blindness Program

- List of parasites (human)

- Neglected tropical diseases

- Rodolfo Robles

- United Front Against Riverblindness

- Harold Ridley (ophthalmologist)

References

- "Onchocerciasis Fact sheet N°374". World Health Organization. March 2014. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "Onchocerciasis (also known as River Blindness) Prevention & Control". Parasites. CDC. May 21, 2013. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Murray, Patrick (2013). Medical microbiology (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. p. 792. ISBN 9780323086929. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Brunette, Gary W. (2011). CDC Health Information for International Travel 2012 : The Yellow Book. Oxford University Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780199830367. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- "Onchocerciasis (also known as River Blindness)". Parasites. CDC. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "Parasites – Onchocerciasis (also known as River Blindness) Epidemiology & Risk Factors". CDC. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "Onchocerciasis (also known as River Blindness) Diagnosis". Parasites. CDC. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Lok, James B.; Walker, Edward D.; Scoles, Glen A. (2004). "9. Filariasis". In Eldridge, Bruce F.; Edman, John D.; Edman, J. (eds.). Medical entomology (Revised ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. p. 301. ISBN 9781402017940. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Reddy M, Gill SS, Kalkar SR, Wu W, Anderson PJ, Rochon PA (October 2007). "Oral drug therapy for multiple neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review". JAMA. 298 (16): 1911–24. doi:10.1001/jama.298.16.1911. PMID 17954542.

- Stewart; Boussinesq; Coulson; Elson; Nutman; Bradley (September 1999). "Onchocerciasis modulates the immune response to mycobacterial antigens". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 117 (3): 517–523. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01015.x. PMC 1905356. PMID 10469056.

- Baldo L, Desjardins CA, Russell JA, Stahlhut JK, Werren JH (2010-02-17). "Accelerated microevolution in an outer membrane protein (OMP) of the intracellular bacteria Wolbachia". BMC Evol Biol. 10: 10:48. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-48. PMC 2843615. PMID 20163713.

- Francesca Tamarozzi; Alice Halliday; Katrin Gentil; Achim Hoerauf; Eric Pearlman; Mark J. Taylor (2011-07-24). "Onchocerciasis: the Role of Wolbachia Bacterial Endosymbionts in Parasite Biology, Disease Pathogenesis, and Treatment". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 24 (3): 459–468. doi:10.1128/CMR.00057-10. PMC 3131055. PMID 21734243.

- Wani, MG (February 2008). "Onchocerciasis". Southern Sudan Medical Journal. Archived from the original on 2011-01-15.

- Ali MM, Baraka OZ, AbdelRahman SI, Sulaiman SM, Williams JF, Homeida MM, Mackenzie CD (15 February 2003). "Immune responses directed against microfilariae correlate with severity of clinical onchodermatitis and treatment history". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 187 (4): 714–7. doi:10.1086/367709. JSTOR 30085595. PMID 12599094.

- Murdoch ME, Hay RJ, Mackenzie CD, Williams JF, Ghalib HW, Cousens S, Abiose A, Jones BR (September 1993). "A clinical classification and grading system of the cutaneous changes in onchocerciasis". Br J Dermatol. 129 (3): 260–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb11844.x. PMID 8286222.

- Abiose, Adenike (March 1993). "A clinical classification and grading system of the cutaneous changes in onchocerciasis". British Journal of Dermatology. 129 (3): 260–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb11844.x. PMID 8286222.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-12-20. Retrieved 2011-01-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dowell SF, Sejvar JJ, Riek L, Vandemaele KA, Lamunu M, Kuesel AC, Schmutzhard E, Matuja W, Bunga S, Foltz J, Nutman TB, Winkler AS, Mbonye AK (2013). "Nodding syndrome". Emerg Infect Dis. 19 (9): 1374–3. doi:10.3201/eid1909.130401. PMC 3810928. PMID 23965548.

- "Parasites - Onchocerciasis (also known as River Blindness)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019-04-19.

- "Life Cycle". Stanford University.

- James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; Elston, Dirk M; Odom, Richard B. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6. OCLC 62736861.

- Marty AM. "Filariasis". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 2009-09-27. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- "Onchocerciasis Control Programme (OCP)". Programmes and Projects. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2009-11-24. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- "African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC)". Programmes and Projects. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2009-08-28. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- "Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas (OEPA)". Programmes and Projects. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2011-04-16. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- "NEWS SCAN: Columbia ousts river blindness; Vaccine-derived polio in India; Danish Salmonella trends". CIDRAP News. July 30, 2013. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017.

- "Brazil and Venezuela border is the last place in the Americas with river blindness". Outbreak News Today. 2015-09-29. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- "Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas (OEPA)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- "Onchocerciasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Sauerbrey, M (September 2008). "The Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas (OEPA)". Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 102 Suppl 1: 25–9. doi:10.1179/136485908x337454. PMID 18718151.

- "2020 vision of a vaccine against river blindness". riverblindnessvaccinetova.org.

- Peter J. Hotez, Maria Elena Bottazzi, Bin Zhan, Benjamin L. Makepeace, Thomas R. Klei, David Abraham, David W. Taylor, and Sara Lustigman, Roger K Prichard (January 2015). "The Onchocerciasis Vaccine for Africa—TOVA—Initiative". PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 9 (1): e0003422. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003422. PMC 4310604. PMID 25634641.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Rea PA, Zhang V, Baras YS (2010). "Ivermectin and River Blindness". American Scientist. 98 (4): 294–303. Archived from the original on 2010-07-05. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-05-24. Retrieved 2017-05-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Trattler, Bill; Gladwin, Mark (2007). Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple. Miami: MedMaster. ISBN 978-0-940780-81-1. OCLC 156907378.

- Taylor MJ, Bandi C, Hoerauf A (2005). Wolbachia bacterial endosymbionts of filarial nematodes. Advances in Parasitology. 60. pp. 245–84. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(05)60004-8. ISBN 9780120317608. PMID 16230105.

- Hoerauf A (2008). "Filariasis: new drugs and new opportunities for lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 21 (6): 673–81. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328315cde7. PMID 18978537. S2CID 26046513.

- Yates DM, Wolstenholme AJ (August 2004). "An ivermectin-sensitive glutamate-gated chloride channel subunit from Dirofilaria immitis". International Journal for Parasitology. 34 (9): 1075–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.010. PMID 15313134.

- Harder A (2002). "Chemotherapeutic approaches to nematodes: current knowledge and outlook". Parasitology Research. 88 (3): 272–7. doi:10.1007/s00436-001-0535-x. PMID 11954915. S2CID 41860363.

- Wolstenholme AJ, Rogers AT (2005). "Glutamate-gated chloride channels and the mode of action of the avermectin/milbemycin anthelmintics". Parasitology. 131 (Suppl:S85–95): S85–95. doi:10.1017/S0031182005008218. PMID 16569295.

- Ejere HO, Schwartz E, Wormald R, Evans JR (2012). "Ivermectin for onchocercal eye disease (river blindness)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 8 (8): CD002219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002219.pub2. PMC 4425412. PMID 22895928.

- "Moxidectin tablets, for oral use" (PDF). www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Onchocerciasis (river blindness)". www.who.int. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Epidemiology". Stanford University. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-22.

- Vinayak M Gaware, Kiran B Dhamak1, Kiran B Kotade, Ramdas T Dolas, Sachin B Somwanshi, Vikrant K Nikam, Atul N Khadse. "ONCHOCERCIASIS: AN OVERVIEW" (PDF). PhOL - PharmacologyOnLine.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Peña Flores G.; Richards F.; et al. (2010). "Lack of Onchocerca volvulus transmission in the northern focus in Chiapas". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 83 (1): 15–20. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0626. PMC 2912569. PMID 20595471.

- Peña Flores G.; Richards F.; Domínguez A. (2010). "Interruption of transmission of Onchocerca volvulus in the Oaxaca focus". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 83 (1): 21–27. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0544. PMC 2912570. PMID 20595472.

- Zimmerman, PA; Katholi, CR; Wooten, MC; Lang-Unnasch, N; Unnasch, TR (May 1994). "Recent evolutionary history of American Onchocerca volvulus, based on analysis of a tandemly repeated DNA sequence family". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 11 (3): 384–92. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040114. PMID 7516998.

- O’Neill, John (1875). "O'Neill J. On the presence of a filaria in craw-craw" (PDF). The Lancet. 105 (2686): 265–266. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)30941-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-02-02.

- "A Short History of Onchocerciasis". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Robles, Roberto (1917). "Enfermedad nueva en Guatemala". La Juventud Médica.

- Strong, Richard (1942). Stitt's Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of tropical diseases. The Blakiston.

- Manson-Bahr, Philip H (1943). Tropical diseases; a manual of the diseases of warm climates [Internet] (11th ed.). Williams & Wilkins Co.

- Blacklock, DB (22 January 1927). "The Insect Transmission of Onchocerca Volvulus (Leuckart, 1893): The Cause of Worm Nodules in Man in Africa". British Medical Journal. 1 (3446): 129–33. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3446.129. PMC 2453973. PMID 20772951.

- Kluxen, G; Hoerauf, A (2008). "The significance of some observations on African ocular onchocerciasis described by Jean Hissette (1888-1965)". Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 307: 53–8.

- Hisette, Jean (1932). Mémoire sur l'Onchocerca volvulus Leuckart et ses manifestations oculaires au Congo belge. pp. 433–529.

- Ridley, Harold (1945). "OCULAR ONCHOCERCIASIS Including an Investigation in the Gold Coast". Br J Ophthalmol. 29 (Suppl): 3–58. doi:10.1136/bjo.29.suppl.3. PMC 513929. PMID 18170175.

- Kluxen, G. "Harvard African Expedition [Internet]". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Thylefors B, Alleman MM, Twum-Danso NA (May 2008). "Operational lessons from 20 years of the Mectizan Donation Program for the control of onchocerciasis". Trop Med Int Health. 13 (5): 689–96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02049.x. PMID 18419585.

- Jan Andersson; Hans Forssberg; Juleen R. Zierath (5 October 2015), Avermectin and Artemisinin - Revolutionary Therapies against Parasitic Diseases (PDF), The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2015, retrieved 5 October 2015

- Kinship Powerful in River Blindness Fight. Carter Center Update, The Carter Center, Atlanta, Georgia. Summer, 2016. pp. 4-5.

- Allen JE, Adjei O, Bain O, Hoerauf A, Hoffmann WH, Makepeace BL, Schulz-Key H, Tanya VN, Trees AJ, Wanji S, Taylor DW (April 2008). Lustigman S (ed.). "Of Mice, Cattle, and Humans: The Immunology and Treatment of River Blindness". PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2 (4): e217. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000217. PMC 2323618. PMID 18446236.

- "River blindness resistance fears". BBC News. 2007-06-14. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- Osei-Atweneboana MY, Eng JK, Boakye DA, Gyapong JO, Prichard RK (June 2007). "Prevalence and intensity of Onchocerca volvulus infection and efficacy of ivermectin in endemic communities in Ghana: a two-phase epidemiological study". Lancet. 369 (9578): 2021–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60942-8. PMID 17574093. S2CID 30650856.

- [No author listed] (11 July 2009). "Fighting river blindness and other ills". Lancet. 374 (9684): 91. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61262-9. PMID 19595328. S2CID 13401341. (editorial)

- Abegunde AT, Ahuja RM, Okafor NJ (2016). "Doxycycline plus ivermectin versus ivermectin alone for treatment of patients with onchocerciasis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1 (1): CD011146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011146.pub2. PMC 5029467. PMID 26771164.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Look up onchocerciasis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |