Royal Prussia

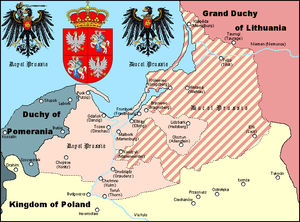

Royal Prussia (Polish: Prusy Królewskie; German: Königlich-Preußen or Preußen Königlichen Anteils, Kashubian: Królewsczé Prësë) or Polish Prussia[1] (Polish: Prusy Polskie;[2] German: Polnisch-Preußen)[3] was a break-away territory of the Teutonic Order that in 1466 won autonomy as a dependency of the King of Poland. Subsequently, in 1569 Royal Prussia was fully merged into the Kingdom of Poland.[4]

| Royal Prussia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous dependency of the King of Poland | |||||||||

| 1466–1569 | |||||||||

_Lob.svg.png) Flag

| |||||||||

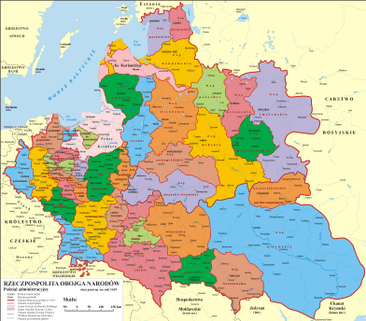

Map of Royal Prussia (light pink) | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 19 October 1466 | |||||||||

| 1 July 1569 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Royal Prussia was established after the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), from territory in western Prussia which seceded from the despotic State of the Teutonic Order seeking protection as a dependency of the King of Poland.[5][6] As a dependency, its political status was similar to the Bailiwick of Jersey (between France and the United Kingdom), reflected in the title "Royal Prussia" or the King's Prussia. Royal Prussia retained autonomy, governing itself and maintaining its indigenous laws, customs, and rights. As a royal dependency, it could participate in the election of its titular monarch, however it could not participate in the Sejm, the Polish parliament.[7]

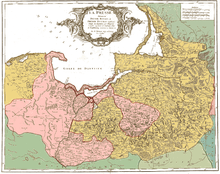

In 1772, the former territories of Royal Prussia were annexed by Prussia. This occurred at the time of the First Partition of Poland, when much of it was formed into the province of West Prussia, while the vast bulk of the Polish Commonwealth itself was incorporated into the Russian Empire; and the ancient Commonwealth, with its "golden liberty", was dismembered.

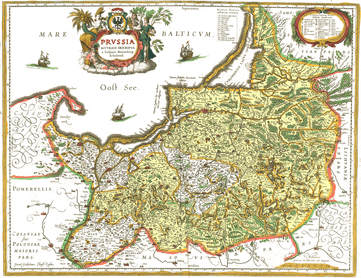

Geography

The area consisted of the following districts:

- Pomerelia and Danzig,

- Kulmerland and Michelauer Land and Thorn,

- the mouth of the Vistula with Elbing and Marienburg,

- the Bishopric of Warmia (Ermland) with Allenstein which were forcibly ceded from the Teutonic Order in the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) to the Kingdom of Poland.[8]

From the 14th century, in old texts (until the 16th or 17th century) and in Latin, the terms Prut(h)enia and Prut(h)enic refer not only to the original settlement area of the now extinct Old Prussians along the Baltic coast east of the Vistula River, but also to the adjacent lands of the former Samboride dukes of Pomerelia, which territory the Teutonic Knights had acquired from the king of Poland in the 1343 Treaty of Kalisz and incorporated into the Order's State.

.

Pomerelia Lauenburg and Bütow Land to the west was ruled by the Pomeranian dukes, enfeoffed to the king of Poland.

Royal Prussia is distinguished from later Ducal Prussia, the remaining (eastern) parts of Prussia around Königsberg, founded and governend by the Teutonic Knights. After secularisation in 1525, it succeeded to the Protestant dukes of the Hohenzollern dynasty. From 1618 this area was in personal union by the Electors of Brandenburg (Brandenburg-Prussia). In 1657 the titular monarchy devolved by the Treaty of Wehlau.

History

By 1308 the Pomerelian part of the region was conquered by the first Polish state, enjoying autonomy and self-government.[9] During the rule of Władysław I the Elbow-high of Poland, the Margraviate of Brandenburg staked its claim on the territory in 1308, leading Władysław to request assistance from the Teutonic Knights, who had replaced the Brandenburgers and incorporated Pomerelia into the Teutonic Order state, in 1309 (Teutonic takeover of Danzig (Gdańsk) and Treaty of Soldin (Myślibórz)).

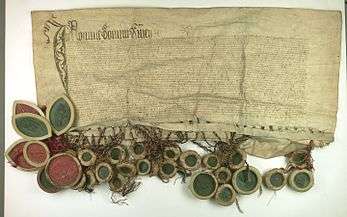

After being checked at the Battle of Grunwald, the Teutonic Knights’s prestige declined, and by the 1411 Peace of Thorn were forced to pay large contributions to the king of Poland, which became a financial burden on the citizenry. In 1440, as the tax burden rose, indigenous nobles and Hanseatic cities established the Prussian Confederation at Marienwerder (Kwidzyn) in resistance of the Order's domestic and financial policies. The Confederation was led by the citizens of Danzig, Elbing, and Thorn. The gentry from Chełmno Land and Pomerelia participated as well. Grand Master Ludwig von Erlichshausen demanded the dissolution and in 1453 searched for help from Pope Nicholas V and Emperor Frederick III. In turn, in February 1454, the Confederation sent a delegation, under Johannes von Baysen, to King Casimir IV Jagiellon of Poland, to ask him for support against the Teutonic Order's rule and for incorporation of their homeland into the Kingdom of Poland. In this treaty, Prussian delegates declared the Polish king the only true sovereign of their lands, justified by the historical fact that the king of Poland had earlier ruled them. After lengthy negotiation, on 6 March 1454, the Royal Chancellery issued the Act of Treaty formalizing the terms of the treaty establishing Royal Prussia’s autonomy as a foreign dependency of the king.[10]

Prussian–Polish Alliance

After the Prussian Confederation pledged allegiance to Casimir on 6 March 1454, the Thirteen Years' War ("War of the Cities") began. King Casimir IV Jagiellon appointed Baysen as the first war-time governor of Royal Prussia. On May 28, 1454, the king took an oath of allegiance from the citizens of Thorn, and in June a similar oath from the citizens of Elbing and Königsberg was taken.[10]

The rebellion also included major cities from the eastern part of the Order's lands, such as Kneiphof, later a part of Königsberg. Though the Knights were victorious at the Battle of Chojnice in 1454, they were not able to finance more knights in order to reconquer the castles occupied by the insurgents. Thirteen years of attrition warfare ended in October 1466 with the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), which provided for the Order's cession to the Polish Crown of its rights over the western half of Prussia, including Pomerelia and the districts of Elbing, Marienburg, and Chełmno.

Independence protected by the king of Poland

According to the 1454 treaty signed by King Casimir IV, Royal Prussia enjoyed complete autonomy as a dependency of the king: it had its own laws, rights, treasury, money, and armies.[9] It governed itself in council, whose members were chosen from local lords and powerful burghers (ius indigenatus). Eventually, Royal Prussia was privileged to send one, non-voting observer to the Sejm (Polish Diet). Thorn, Elbing, and Danzig (Danzig law) were granted additional privileges similar to the status of a Free imperial city.

In many respects, the constitutional status of Royal Prussia was similar to the Bailiwick of Jersey or the Isle of Man, which are ruled by the monarch of the United Kingdom. Royal Prussia, as a vassal state answerable to the King of Poland alone, benefited from its association with the Commonwealth, and owing to its liberties under the Polish monarch, its rulers ranked as the most powerful among palatines of the Commonwealth.

The Bishop of Warmia had claimed Imperial Prince-Bishopric status, as mentioned in the Golden Bull of 1356 by Emperor Charles IV. Although the area was never directly under the Emperor's jurisdiction and the claim seems unsupported by any bestowal document, it was in wide use in the 17th century. The bishopric continued defending this status until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.

Integration into the Kingdom of Poland

In 1569, Royal Prussia was integrated fully into the Kingdom of Poland, and its parliament reduced to the status of a provincial assembly, also separate Prussian institutions were dissolved.[4] The former territory was subsequently governed as Pomeranian Voivodeship, Culm Voivodeship, Malbork Voivodeship, and Prince-Bishopric of Warmia

History of Brandenburg and Prussia | ||||

| Northern March 965–983 |

Old Prussians pre-13th century | |||

| Lutician federation 983 – 12th century | ||||

| Margraviate of Brandenburg 1157–1618 (1806) (HRE) (Bohemia 1373–1415) |

Teutonic Order 1224–1525 (Polish fief 1466–1525) | |||

| Duchy of Prussia 1525–1618 (1701) (Polish fief 1525–1657) |

Royal (Polish) Prussia (Poland) 1454/1466 – 1772 | |||

| Brandenburg-Prussia 1618–1701 | ||||

| Kingdom in Prussia 1701–1772 | ||||

| Kingdom of Prussia 1772–1918 | ||||

| Free State of Prussia (Germany) 1918–1947 |

Klaipėda Region (Lithuania) 1920–1939 / 1945–present |

Recovered Territories (Poland) 1918/1945–present | ||

| Brandenburg (Germany) 1947–1952 / 1990–present |

Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia) 1945–present | |||

Partitions

At the same time as the 1772 First Partition of Poland, the former lands of Royal Prussia were annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia, the successor state of the Teutonic Order. In 1793, the new Kingdom of Prussia participated in the Second Partition of Poland by temporarily annexing the neighboring regions, which were almost immediately returned to the Tsarist kingdom of Poland and incorporated into the Russian Empire.

Governors

- 1454–1459: Johannes von Baysen, war-time governor

- 1459–1480: Stibor (Tiburcius) von Baysen[11]

- 1480: Niklas von Baysen, who was only elected; he refused to swear allegiance to the king. He was also Voivode of Malbork.

In 1510, after several attempts to install another governor, the office was abolished.

See also

- Ducal Prussia

- Duchy of Prussia

- Kingdom of Prussia

- Pomerelia

- Kursenieki

- Kashubia

- Warmia

- The plague during the Great Northern War

References

- Anton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. A New System of Geography, London 1762, p. 588

- Zygmunt Gloger (1900). "Volume 325". In Harvard Slavic humanities preservation microfilm project (ed.). Geografia historyczna ziem dawnej polski (Historical Geography of the former Polish lands) (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Polska. pp. 82, 144.

- (in German) Polnisch-Preußen ("State Constitution of Polish-Prussia") (see: Excerpt in the publication of 1764, p. 581)

- Daniel Stone (2001). The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-295-98093-1.

- Knoll, Paul W. (2008). "The Most Unique Crusader State. The Teutonic Order in the Development of the Political Culture of Northeastern Europe during the Middle Ages". In Ingrao, Charles W.; Szabo, Franz A. J. (eds.). The Germans and the East. Purdue University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1557534439.

- Dwyer, Philip G., ed. (2000). The Rise of Prussia 1700-1830. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1138837645.

- Frost, Robert, The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Vol. I

- Stone, Daniel. A History of East Central Europe. University of Washington Press, 2001, ISBN 0-295-98093-1. p. 30

- Frost, Robert, The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania,’’ Vol. I

- F. Kiryk, B. Ryś (red.) Wielka Historia Polski, t. II 1320-1506, Kraków 1997, p. 160-161

- Acten der Ständetage Preussens unter der Herrschaft des Deutschen Ordens: 5 vols., Max Toeppen (ed.), Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1874–1886; reprint Aalen: Scientia, 1968–1974, vol. 5: 'Die Jahre 1458–1525', 1974. p. 90]. ISBN 3-511-02940-6.

Further reading

- Karin Friedrich, The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-58335-7 on Google Books

- Gerard Labuda (ed.), Historia Pomorza, vol. I–IV, Poznań 1969–2003 (also covers East Prussia) (in Polish)

- W. Odyniec, Dzieje Prus Królewskich (1454–1772). Zarys monograficzny, Warszawa 1972 (in Polish)

- Dzieje Pomorza Nadwiślańskiego od VII wieku do 1945 roku, Gdańsk 1978 (in Polish)