Locarno Treaties

The Locarno Treaties were seven agreements negotiated at Locarno, Switzerland, on 5–16 October 1925 and formally signed in London on 1 December, in which the First World War Western European Allied powers and the new states of Central and Eastern Europe sought to secure the post-war territorial settlement, and return normalizing relations with the defeated German Reich (the Weimar Republic). It also stated that Germany would never go to war with the other countries. Locarno divided borders in Europe into two categories: western, which were guaranteed by Locarno treaties, and eastern borders of Germany with Poland, which were open for revision.

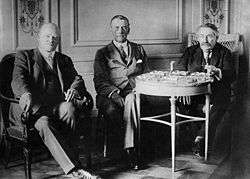

From left to right, Gustav Stresemann, Austen Chamberlain and Aristide Briand during the Locarno negotiations | |

| Type | Multilateral treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | 1 December 1925 |

| Location | London, England, UK |

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye |

|

Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine |

|

Treaty of Trianon |

Planning the treaties

German foreign minister Gustav Stresemann made his highest priority the restoration of German prestige and privileges as a leading European nation. French withdrawal from the Occupation of the Ruhr was scheduled for January 1925, but Stresemann sensed that France was very nervous about its security and might cancel the withdrawal. Having realized that France deeply desired a British guarantee of its postwar borders, but that London was reluctant, Stresemann came up with a plan whereby all sides would get what they wanted: through a series of treaties that promised these guarantees. Upon hearing this proposal, British Foreign Minister Austen Chamberlain enthusiastically agreed. France realized that its occupation of the Ruhr had caused financial and diplomatic damage than it was worth. The foreign ministers then convened in the Swiss resort of Locarno in October 1925, where they came to an agreement on the treaties.

The first treaty was the most critical: a mutual guarantee of the frontiers of Belgium, France, and Germany, guaranteed by Britain and Italy. The second and third treaties called for arbitration between Germany and Belgium, and Germany and France, regarding future disputes. The fourth and fifth were similar arbitration treaties between Germany and Poland, and Germany and Czechoslovakia. Poland especially, and Czechoslovakia as well, felt threatened by the Locarno agreements and these treaties were an attempt to reassure them. Thanks to the Dawes Plan, Germany was now making regular reparations payments. The success of the Locarno agreements led to the admission of Germany to the League of Nations in September 1926, with a seat on its council as a permanent member.[1]

Goals

For the British government, the main goals were promoting Franco-German reconciliation, and the expectation that reconciliation would lead to France dissolving its Cordon sanitaire, as the French alliance system in Eastern Europe was known between the wars.[2] If France were to dissolve its alliances in Eastern Europe, Poland would peacefully hand over the territories ceded by Germany in the Versailles Peace Treaty: the Polish Corridor, the Free City of Danzig (modern Gdańsk, Poland) and Upper Silesia.[3]

Parties and agreement

The principal treaty concluded at Locarno was the Rhineland Pact between Germany, France, Belgium, Great Britain, and Italy. Germany formally recognised its new western borders acted by the Treaty of Versailles. Furthermore, the first three signatories undertook not to attack each other, with the latter two acting as guarantors. In the event of aggression by any of the first three states against another, all other parties were to assist the country under attack.[4]

Germany also agreed to sign arbitration conventions with France and Belgium and arbitration treaties with Poland and Czechoslovakia, undertaking to refer future disputes to an arbitration tribunal or to the Permanent Court of International Justice.

France signed further treaties with Poland and Czechoslovakia, pledging mutual assistance in the event of conflict with Germany. These essentially reaffirmed existing treaties of alliance concluded by France with Poland on 19 February 1921 and with Czechoslovakia on 25 January 1924. These treaties also showed that relations between France and Germany had not improved to a large extent.

Effect

The Locarno Treaties marked a dramatic improvement in the political climate of western Europe in 1925–1930. They promoted expectations for continued peaceful settlements, often called the "spirit of Locarno". This spirit was made concrete when Germany joined the League in 1926, and the withdrawal of Allied troops occupying Germany's Rhineland.[5] The Nobel Peace Prize was given to the lead negotiators of the treaty, going to Sir Austen Chamberlain in 1925 and jointly to Aristide Briand and Gustav Stresemann in 1926.

Historian Sally Marks says:

Henceforth the spirit of Locarno would reign, substituting conciliation for enforcement as the basis for peace. Yet for some peace remained a desperate hope rather than an actuality. A few men knew that the spirit of Locarno was a fragile foundation on which to build a lasting peace.[6]

Hitler repudiated Locarno by sending troops into the demilitarized Rhineland on 7 March 1936.

Anger in Poland

In Poland, the public humiliation received by Polish diplomats was one of the contributing factors to the fall of the Grabski cabinet. Locarno contributed to the worsening of the atmosphere between Poland and France, weakening the French-Polish alliance. Józef Beck ridiculed the treaties saying, "Germany was officially asked to attack the east, in return for peace in the west."[7] Józef Piłsudski would say that "every honest Pole spits when he hears this word [Locarno]".[8] Proposals in 1934 for an "eastern Locarno" pact securing Germany's eastern frontiers foundered on German opposition and on Poland's insistence that its eastern borders should be covered by a western guarantee of her borders. The Locarno treaty was heavily undermined by the Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance on 2 May 1935, which the German government claimed was a violation of its "spirit".

See also

Notes

- Norman Rich, Great Power Diplomacy since 1914 (2003) pp 148–49.

- Stephen Schuker, “The End of Versailles” pages 38–56 in Gordon Martel, ed. The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered (1999) pp 48–49.

- Schuker, “The End of Versailles” in The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered pp 48–49; J W Bruegel, "German Diplomacy and the Sudeten Question before 1938" in International Affairs vol. 37 no. 3 (Jul 1961): 323-326, discusses the lack of German revisionism towards German-speaking Czechoslovakia in the 1920s.

- Jon Jacobson, Locarno diplomacy: Germany and the west, 1925–1929 (2015)

- Bo Stråth (2016). Europe's Utopias of Peace: 1815, 1919, 1951. Bloomsbury. p. 398. ISBN 9781474237741.

- Sally Marks (2003). The Illusion of Peace: International Relations in Europe 1918–1933. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 89. ISBN 9781137127327.

- Michael Brecher (2016). The World of Protracted Conflicts. Lexington Books. p. 204.

- Piotr Wandycz, France and Her Eastern Allies 1919–1925: French-Czechoslovak-Polish Relations from the Paris Peace Conference to Locarno (1962).

Further reading

- Cohrs, Patrick O. "The First 'Real' Peace Settlements after the First World War: Britain, the United States and the Accords of London and Locarno, 1923–1925," Contemporary European History, (Feb 2003) 12#1 pp 1–31

- Jacobson, Jon. Locarno diplomacy: Germany and the west, 1925–1929 (Princeton UP, 2015).

- Johnson, Gaynor. Locarno Revisited: European Diplomacy 1920–1929 (2004) excerpt and text search

- Magee, Frank. "Limited Liability"? Britain and the Treaty of Locarno," Twentieth Century British History, (Jan 1995) 6#1 pp 1–22

- Schuker, Stephen. "The End of Versailles" pages 38–56 from The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered A.J.P. Taylor And The Historians edited by Gordon Martel, Routledge: London, United Kingdom, 1999, ISBN 0-415-16325-0

- Steiner, Zara. The Triumph of the Dark: European International History 1933–1939 (2005) 397–418 explains the winners and losers

- Wright, Jonathan. "Locarno: a democratic peace?" Review of International Studies, (April 2010) 36#2 pp 391–411; online

- Wright, Jonathan, and Julian Wright. "One Mind at Locarno? Aristide Briand and Gustav Stresemann." in Steven Casey and Jonathan Wright eds.Mental Maps in the Era of Two World Wars (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2008P pp. 58–76.

Primary sources

- Berber, F.J. ed. Locarno A Collection Of Documents (1936) online; useful English translations, with a biased anti-French introduction by a leading Nazi

External links

| Look up locarnize in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Text of the Treaties

- Locarno Treaties

- Final Protocol of the Locarno Conference of the same Date and Collective Note to Germany dated London, December 1, 1925, regarding Article 16 of the Covenant of the League of Nations

- Treaty of Mutual Guarantee, done at Locarno, October 16, 1925

- Map of Europe at time of Locarno Treaties at omniatlas.com