North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) (Vietnamese: Việt Nam Dân Chủ Cộng Hòa) (French: République démocratique du Viêt Nam) was a state in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976.

Democratic Republic of Vietnam Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1945—1976 | |||||||||||

Motto: Độc lập – Tự do – Hạnh phúc ("Independence – Freedom – Happiness") | |||||||||||

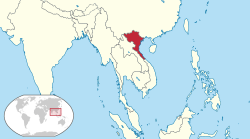

Administrative territory of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in Southeast Asia according to 1954 Geneva Accord | |||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Hanoi 21°01′42″N 105°51′15″E | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Vietnamese | ||||||||||

| Official script | Vietnamese alphabet | ||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhist Catholic Church Confucianism Taoism | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | North Vietnamese | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist dominant-party socialist republic | ||||||||||

| Party Chairman First Secretary | |||||||||||

• 1945–1956 | Trường Chinh | ||||||||||

• 1956–1960 | Hồ Chí Minh | ||||||||||

• 1960–1976 | Lê Duẩn | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1945–1969 | Hồ Chí Minh | ||||||||||

• 1969–1976 | Tôn Đức Thắng | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1945–1955 | Hồ Chí Minh | ||||||||||

• 1955–1976 | Phạm Văn Đồng | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||

| 14 August 1945 | |||||||||||

| 2 September 1945 | |||||||||||

| 6 January 1946 | |||||||||||

| 19 December 1946 | |||||||||||

| 20 July 1954 | |||||||||||

| 1 November 1955 | |||||||||||

| 2 July 1976 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1945 | 331,212 km2 (127,882 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| 1960 | 157,880 km2 (60,960 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| 1974 | 157,880 km2 (60,960 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1945 | 20,000,000[1] | ||||||||||

• 1960 | 15,916,955 | ||||||||||

• 1974 | 23,767,300 | ||||||||||

| Currency | đồng cash (until 1948)[2] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Vietnam | ||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Vietnam | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dominated

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

During the August Revolution following World War II, Vietnamese communist revolutionary Hồ Chí Minh, leader of the Việt Minh, declared independence from French Indochina on 2 September 1945, announcing the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The Việt Minh ("League for the Independence of Vietnam") was a coalition of multiple Vietnamese nationalist groups, mostly led by communists who increasingly marginalized non-communists in the organisation after the reestablishment of the previously banned Communist Party of Vietnam in February 1951.[3]

France moved in to reassert its colonial dominance over Vietnam which led to the First Indochina War in December 1946, a bloody guerrilla war between France and the Việt Minh. The Việt Minh captured and controlled most of the rural areas in Vietnam which led to French defeat in 1954. The negotiations in the Geneva Conference that year ended the war and recognized Vietnamese independence. The Geneva Accords provisionally divided the country into a northern and a southern zone along the 17th parallel, stipulating general elections scheduled for July 1956 to "bring about the unification of Viet-Nam".[4] The northern zone was controlled by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and became commonly called North Vietnam, while the southern zone, under control of the French-established State of Vietnam was commonly called South Vietnam.

Supervision of the implementation of the Geneva Accords was the responsibility of an international commission consisting of India, Canada, and Poland. India represented the non-aligned, Canada the non-communist, and Poland the communist blocs. The United States did not sign the Geneva Accords and stated that it "shall continue to seek to achieve unity through free elections supervised by the United Nations to ensure that they are conducted fairly".[5] In July 1955, the prime minister of the State of Vietnam, Ngô Đình Diệm, announced that South Vietnam would not participate in elections to unify the country. He said that the State of Vietnam had not signed the Geneva Accords and was therefore not bound by it.[6]

After the failure to reunify Vietnam by elections, North Vietnam attempted to unify the country by force, leading to the Vietnam War in 1955. The North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam and the South Vietnam-based Việt Cộng guerrilla fought against the military of South Vietnam (now the Republic of Vietnam) and were backed by their communist allies, mainly China and the Soviet Union.[7] To prevent a spread of communism in Southeast Asia, the United States intervened in the conflict along with other anti-communist forces such as South Korea, Australia and Thailand, who heavily supported South Vietnam militarily. The conflict spread to neighboring countries and North Vietnam supported the Pathet Lao in Laos and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia against their respective US-backed governments. By 1973 the United States and its allies had been forced to withdraw from the war, this left South Vietnam alone and it was swiftly overrun by the superior Northern forces.

The Vietnam War ended on 30 April 1975 and saw South Vietnam come under the control of a Provisional Revolutionary Government, which led to the reunification of Vietnam on 2 July 1976, creating the Socialist Republic of Vietnam of today. The expanded Socialist Republic retained North Vietnam's political culture under Soviet influence and continued its existing memberships in international organisations such as COMECON.[8]

Leadership under Hồ Chí Minh (1945–69)

Proclamation of the republic

After about 300 years of partition by feudal dynasties, Vietnam was again under one single authority in 1802 when Gia Long founded the Nguyễn dynasty, but the country became a French protectorate after 1883 and under Japanese occupation after 1940 during World War II. Soon after Japan surrendered on 2 September 1945, the Việt Minh in the August Revolution entered Hanoi, and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was proclaimed on 2 September 1945: a government for the entire country, replacing the Nguyễn dynasty.[9] Hồ Chí Minh became leader of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt had spoken against French rule in Indochina, and the U.S. was supportive of the Viet Minh at this time.

Early republic

The Democratic Republic of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh claimed dominion over all of Vietnam, but during this time South Vietnam was in profound political disorder. The successive collapse of French, then Japanese power, followed by the dissension among the political factions in Saigon had been accompanied by widespread violence in the countryside.[10][11] On 16 August 1945, Hồ Chí Minh organized the National Congress in Tân Trào. The Congress adopted 10 major policies of the Việt Minh, passed the General Uprising Order, decided the National Flag, in the middle with 5-pointed gold star, selected the national anthem and selected the National Committee for the Liberation of Vietnam, later becoming the Provisional Revolutionary Government, led by Hồ Chí Minh. On 12 September 1945, the first British troops arrived in Saigon. On 23 September 28 days after the people of Saigon seized political power, French troops occupied the police stations, the post office, and other public buildings. The salient political fact of life in Northern Vietnam was Chinese Nationalist army of occupation, and the Chinese presence had forced Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh to accommodate Chinese-backed Viet Nationalists. In June 1946, Chinese Nationalist troops evacuated Hanoi, and on the 15 June, the last detachments embarked at Haiphong. After the departure of the British in 1946, the French controlled a part of Cochinchina, South Central Coast, Central Highlands since the end Southern Resistance War. In January 1946, the Viet Minh held an nationwide election in all of provinces to establish a National Assembly. Public enthusiasm for this event suggests that the Viet Minh enjoyed a great deal of popularity at this time, although there were few competitive races and the party makeup of the Assembly was determined in advance of the vote.[lower-alpha 1] Despite of not joining the election, Việt Cách and Việt Quốc gained 70 seats in the National Assembly for establishing the unified government.[15]

On 18 and 19 September 1945, the Việt Minh held secret meetings with Việt Cách (18 September 1945) and Việt Quốc (19 September 1945). In these two meetings, Nguyễn Hải Thần represented Việt Cách and Nguyễn Tường Tam represent Việt Quốc. Hồ Chí Minh agree to unite the Việt Minh with Việt Cách and Việt Quốc. Thus, the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam led by the Việt Minh will receive the financial and political support of the Republic of China. For this proposal, within the Việt Minh there are many different opinions. Võ Nguyên Giáp disagrees with the suggestion that the proposals are not valid and not honest, as if replacing French colonialism with Chinese domination, but Hoàng Minh Giám thought that the unification of Vietnam With the Nationalist parties will reduce the opposition and strengthen the power of the Việt Minh, as the Chinese are relieved and the French have to worry. Eventually the Việt Minh under Hồ Chí Minh refused to merge with the Pro-Chinese Việt Cách and the Việt Quốc League.[16]

On 6 January 1946, President Hồ Chí Minh held the nationwide General Election which voted for the first time and passed the Constitution. Many parties did not have the right to participate in General Elections seeking to undermine . These parties claimed to be the only Việt Minh communist, the government in the hands of the Việt Minh want anyone to win it. The two opposition parties in the government are the Vietnam's Nationalist Party (Việt Quốc) and the Vietnam Cách mệnh Đồng minh (Việt Cách) did not participate in the election although Hồ Chí Minh previously sent a letter to Nguyễn Hải Thần leader of Việt Cách and Vũ Hồng Khanh leader of Việt Quốc. Hồ Chí Minh invites Việt Quốc and Việt Cách to attend the General Election and urges the two sides not to attack each other with words or actions until the Congress opens. Former Prime Minister Trần Trọng Kim said there were places where people were forced to vote for the Việt Minh.[17] According to the Việt Minh, the election was fair.[17] Despite being campaigned by many parties to campaign for the people to boycott the election and block the election in some places, where there are self-nominated candidates, publicly run, free elections are taking place everywhere. After the election results are announced, the truth is not the same as the propaganda parties. Many prestigious delegates of classes, classes, religions and ethnic groups were elected in the First National Assembly, most of them not party members.[18]

The presence of Chiang Kai-shek's army up to that time ensured the survival of Vietnam's Nationalist Party and Việt Cách. These two parties did not have a cohesive program to enlist the people like the Việt Minh[19] The leaders of the Vietnam's Nationalist Party and the Việt Cách Revolutionary Party are far from having comparable qualities with Hồ Chí Minh, Võ Nguyên Giáp, and other responsible Việt Minh members. When the Chinese nationalist army withdrawal from Vietnam on 15 June 1946, in one way or another, Võ Nguyễn Giáp, decided that the Việt Minh had to completely control the government. Võ Nguyễn Giáp is in immediate action with the goal of spreading Việt Minh leadership: the Allied Powers are supported by the Vietnam's Nationalist Party (according to Cecil B. Currey, this organization borrows the revolutionary name of Vietnam's Nationalist Party of 1930 was founded by Nguyễn Thái Học and, according to David G. Marr, the Vietnamese Communist Party under Hồ Chí Minh tried to banned the Pro-Chinese Nationalist Party in Vietnam[20] betraying the revolutionary cause of Nguyễn Thái Học in 1930. By the end of 1945, many people still did not believe in it.) The pro-Japan nationalist group, the Trotskyists, the anti-French nationalists, the Catholic group called "Catholic soldiers." Võ Nguyễn Giáp has gradually sought to phase out these parties. On 19 June 1946, the Việt Minh Journal reportedly vehemently criticized "reactionaries sabotage the Franco-Vietnamese preliminary agreement on 6 March". Shortly thereafter, Võ Nguyễn Giáp began a campaign to pursue opposition parties by police and military forces controlled by the Việt Minh with the help of the French authorities. He also used soldiers, Japanese officers volunteered to stay in Vietnam and some of the supplies provided by France (in Hòn Gai French troops provided the Việt Minh with cannons to kill some of the positions commanded by the Great Occupation) in this campaign.

When France declared Cochinchina, the southern third of Vietnam, a separate state as the "Autonomous Republic of Cochinchina" in June 1946, Vietnamese nationalists reacted with fury. In November, the National Assembly adopted the first Constitution of the Republic.[21]

During the First Indochina War

The French reoccupied Hanoi and the First Indochina War (1946–54) followed. Following the Chinese Communist Revolution (1946−50), Chinese communist forces arrived on the border in 1949. Chinese aid revived the fortunes of the Viet Minh and transformed it from a guerrilla militia into a standing army. The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 transformed what had been an anti-colonial struggle into a Cold War battleground, with the U.S. providing financial support to the French.

Provisional military demarcation of Vietnam

Following the partition of Vietnam in 1954 at the end of the First Indochina War, more than one million North Vietnamese migrated to South Vietnam,[22] under the U.S.-led evacuation campaign named Operation Passage to Freedom,[23] with an estimated 60% of the north's one million Catholics fleeing south.[24][25] The Catholic migration is attributed to an expectation of persecution of Catholics by the North Vietnamese government, as well as publicity employed by the Saigon government of the President Ngo Dinh Diem.[26] The CIA ran a propaganda campaign to get Catholics to come to the south. However Colonel Edward Lansdale, the man credited with the campaign, rejected the notion that his campaign had much effect on popular sentiment.[27] The Viet Minh sought to detain or otherwise prevent would-be refugees from leaving, such as through intimidation through military presence, shutting down ferry services and water traffic, or prohibiting mass gatherings.[28] Concurrently, between 14,000 and 45,000 civilians and approximately 100,000 Viet Minh fighters moved in the opposite direction.[24][29][30]

Land reform

Land reform was an integral part of the Viet Minh and communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam. A Viet Minh Land Reform Law of 4 December 1953 called for (1) confiscation of land belonging to landlords who were enemies of the regime; (2) requisition of land from landlords not judged to be enemies; and (3) purchase with payment in bonds. The land reform was carried out from 1953 to 1956. Some farming areas did not undergo land reform but only rent reduction and the highland areas occupied by minority peoples were not substantially impacted. Some land was retained by the government but most was distributed without payment with priority given to Viet Minh fighters and their families.[31] The total number of rural people impacted by the land reform program was more than 4 million. The rent reduction program impacted nearly 8 million people.[32]

Results

The land reform program was a success in terms of distributing much land to poor and landless peasants and reducing or eliminating the land holdings of landlords and rich peasants. However it was carried out with violence and repression primarily directed against large landowners identified, sometimes incorrectly, as landlords.[33] On 18 August 1956, North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh acknowledged the serious errors the government had made in the land reform program. Too many farmers, he said, had been incorrectly classified as "landlords" and executed or imprisoned and too many mistakes had been made in redistributing land. Severe rioting protesting the excesses of the land reform program broke out in November 1956 in one largely Catholic rural district. About 1,000 people were killed or injured and several thousand imprisoned. Democratic Republic of Vietnam initiated a "correction campaign" which by 1958 had resulted in the return of land to many of those harmed by the land reform.[34] As part of the correction campaign as many as 23,748 political prisoners were released by North Vietnam by September 1957.[35]

Executions

Executions and imprisonment of persons classified as "landlords" or enemies of the state were contemplated from the beginning of the land reform program. A Politburo document dated 4 May 1953 said that executions were "fixed in principle at the ratio of one per one thousand people of the total population."[36] The number of persons actually executed by communist cadre carrying out the land reform program has been variously estimated. Some estimates of those killed range up to 200,000.[37] Other scholarship has concluded that the higher estimates were based on political propaganda emanating from South Vietnam and that the actual total of those executed was probably much lower. Scholar Edwin E. Moise estimated the total number of executions at between 3,000 and 15,000 and later came up with a more precise figure of 13,500.[38] Moise's conclusions were supported by documents of diplomats from Hungary (occupied by the Soviet Union), living in Democratic Republic of Vietnam at the time of the land reform.[39] Author Michael Lind in a 2013 book gives a similar estimate of "at least ten or fifteen thousand" executed.[40]

Collective farming

The ultimate objective of the land reform program of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam government was not to achieve equitable distribution of farmland but rather the organization of all farmers into co-operatives in which land and other factors of agricultural production would be owned and used collectively.[41] The first steps after the 1953-1956 land reform were the encouragement by the government of labor exchanges in which farmers would unite to exchange labor; secondly in 1958 and 1959 was the formation of "low level cooperatives" in which farmers cooperated in production. By 1961, 86 percent of farmers were members of low-level cooperatives. The third step beginning in 1961 was to organize "high level cooperatives", true collective farming in which land and resources were utilized collectively without individual ownership of land.[42] By 1971, the great majority of farmers in North Vietnam were organized into high-level cooperatives. Collective farms were abandoned gradually in the 1980s and 1990s.[43]

Presidency of Tôn Đức Thắng (1969–76)

During the Vietnam War

Reunification

After the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975, the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam, or Vietcong, alongside the North Vietnamese Army, governed South Vietnam during the period before reunification. However it was seen as a vassal government of North Vietnam.[44][45][46] North and South Vietnam were officially reunited under one state on 2 July 1976, forming the Socialist Republic of Vietnam which continues to administer the country today.

Foreign relations

South Vietnam

From 1960, the North Vietnamese government went to war with the Republic of Vietnam via its proxy the Viet Cong, in an attempt to annex South Vietnam and reunify Vietnam under a communist party.[47] North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces and supplies were sent along the Ho Chi Minh trail. In 1964 the United States sent combat troops to South Vietnam to support the South Vietnamese government, but the U.S. had advisors there since 1950. Other nations, including Australia, the Republic of Korea, Thailand and New Zealand also contributed troops and military aid to South Vietnam's war effort. China and the Soviet Union provided aid to and troops in support of North Vietnamese military activities. This was known as the Vietnam War, or the American War in Vietnam itself (1955–75). In addition to the Viet Cong in South Vietnam, other communist insurgencies also operated within neighboring Kingdom of Laos and Khmer Republic, both formerly part of the French colonial territory of Indochina. These were the Pathet Lao and the Khmer Rouge, respectively. These insurgencies were aided by the North Vietnamese government, which sent troops to fight alongside them.

Communist and capitalist states

Democratic Republic of Vietnam was diplomatically isolated by many capitalist states, and many other anti-communist states worldwide throughout most of the North's history, as these states extended recognition only to the anti-communist government of South Vietnam. North Vietnam however, was recognized by almost all Communist countries, such as the Soviet Union and other Socialist countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, China, North Korea, and Cuba, and received aid from these nations. North Vietnam refused to establish diplomatic relations with Yugoslavia from 1950 to 1957, perhaps reflecting Hanoi's deference to the Soviet line on the Yugoslav government of Josip Broz Tito, and North Vietnamese officials continued to be critical of Tito after relations were established.[48][49] Several non-aligned countries also recognized North Vietnam, mostly, similar to India, according North Vietnam de facto rather than de jure (formal) recognition.[50]

In 1969, Sweden became the first Western country to extend full diplomatic recognition to North Vietnam.[51] Many other Western countries followed suit in the 1970s, such as the government of Australia under Gough Whitlam.

See also

Notes

- Although former emperor Bao Dai was also popular at this time and won a seat in the Assembly, the election did not allow voters to express a preference between Bao Dai and Ho Chi Minh. It was held publicly in northern and central Vietnam, but secretly in Cochinchina, the southern third of Vietnam. There was minimal campaigning and most voters had no idea who the candidates were.[12] In many districts, a single candidate ran unopposed.[13] Party representation in the Assembly was publicly announced before the election was held.[14]

References

- https://news.zing.vn/ky-uc-kinh-hoang-ve-nan-doi-70-nam-truoc-o-viet-nam-post447751.html

- "Sapeque and Sapeque-Like Coins in Cochinchina and Indochina (交趾支那和印度支那穿孔錢幣)". Howard A. Daniel III (The Journal of East Asian Numismatics – Second issue). 20 April 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ' Ho Chi Minh and the Communist Movement in Indochina, A Study in the Exploitation of Nationalism Archived 2014-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (1953), Folder 11, Box 02, Douglas Pike Collection: Unit 13 - The Early History of Vietnam, The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University.'

- "Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities in Vietnam, July 20, 1954, https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/genevacc.htm Archived 2015-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 15 Oct 2015

- "Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities in Vietnam, July 20, 1954, https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/genevacc.htm Archived 2015-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 15 Oct 2015; "Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference of the Problem of Restoring Peace in Indo-China, July 21, 1954, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Geneva_Conference Archived 2015-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 15 Oct 2015

- Ang Cheng Guan (1997). Vietnamese Communists' Relations with China and the Second Indochina War (1956–62). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7864-0404-9. Archived from the original on 2017-07-13. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History (2019) pp 223–265.

- "Author Tim O'Brien, voice of the Vietnam War experience"..

- "Báo Nhân Dân - Phiên bản tiếng Việt - Trang chủ". Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- Pentagon Papers [ Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense 1969] Retrieved 28/09/12

- Pentagon Papers Pentagon Papers Archived 2011-06-13 at WebCite 1969 Retrieved 28/09/12

- Fall, Bernard, The Viet-Minh Regime Archived 2016-05-27 at the Wayback Machine (1956), p. 9.

- Fall, p. 10.

- Springhal, John, Decolonization since 1945 (1955), p. 44.

- "Quốc hội khóa 1 và những giây phút không thể nào quên". 5 January 2016.

- Why Vietnam, Archimedes L.A Patti, Nhà xuất bản Đà Nẵng, 2008, trang 544 - 545

- Sexton, Michael "War for the Asking" 1981

- Stanley Karnow. Vietnam: A History. New York, NY. Penguin, 1991, p. 163.

- s:Page:Pentagon-Papers-Part I.djvu/30

- David G. Marr, Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution (1945–1946), page 415, California: University of California Press, 2013

- "Political Overview Archived 2009-05-11 at the Wayback Machine"

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "The State of The World's Refugees 2000 – Chapter 4: Flight from Indochina" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2007..

- Lindholm, Richard (1959). Viet-nam, the first five years: an international symposium. Michigan State University Press. p. 49.

- Tran, Thi Lien (November 2005). "The Catholic Question in North Vietnam". Cold War History (London: Routledge) 5 (4): 427–49. doi:10.1080/14682740500284747.

- Jacobs, Seth (2006). Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-4447-8. p. 45

- Truong Nhu Tang. 1986. A Viet Cong Memoir. Vintage.

- Hansen, pp. 182–183.

- Frankum, Ronald (2007). Operation Passage to Freedom: The United States Navy in Vietnam, 1954–55. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-608-6. p. 159/160/190

- Frankum, Ronald (2007). Operation Passage to Freedom: The United States Navy in Vietnam, 1954–55. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-608-6.

- Ruane, Kevin (1998). War and Revolution in Vietnam. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85728-323-5.

- Moise, Edward E. (1983), Land Reform in China and North Vietnam, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 178-181

- Szalontai, Balazs (2005), "Political and Economic Crisis in Democratic Republic of Vietnam, 1955-1956", Cold War History, Vol. 5, No. 4, p. 401. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Vo, Alex Thai D. (Winter 2015). "Nguyễn Thị Năm and the Land Reform in North Vietnam, 1953". Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 10 (1): 9–10, 14, 36. doi:10.1525/vs.2015.10.1.1.

- Moise, pp. 237-268

- Szalontai, p. 401

- "Politburo's Directive Issued on May 4, 1953, on some Special Issues regarding Mass Mobilization," Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Summer 2010), p. 243. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Lam Thanh Liem (2005), "Ho Chi Minh's Land Reform: Mistake or Crime," http://www.paulbogdanor.com/left/vietnam/landreform.html Archived 2013-02-18 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4 October 2015

- Moise, pp. 205-222; "Newly released documents on the land reform", Vietnam Studies Group, https://web.archive.org/web/20110420044800/http://www.lib.washington.edu/southeastasia/vsg/elist_2007/Newly%20released%20documents%20on%20the%20land%20reform%20.html, accessed 1 March 2017.

- Balazs, p. 401

- Lind, Michael (2003), Vietnam: The Necessary War, New York: Simon and Schuster, p. 155

- Moise, pp. 155-159

- Kerkvliet, Bendedict J. Tria (1998), "Wobbly Foundations" building co-operatives in rural Vietnam, 1955-61," South East Research, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 193-197. Downloaded from JSTOR

- Pingali, and Vo-TungPrabhu and Vo-Tong Xuan (1992), "Vietnam: Decollectivization and Rice Productive Growth", Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol 40, No 4. p. 702, 706-707. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Senauth, Frank Archived 2016-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, The Making of Vietnam, 2012, p. 54.

- Nguyễn, Sài Đình Archived 2013-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, The National Flag of Viet Nam: Its Origin and Legitimacy, p. 4.

- Emering, Edward J. Archived 2017-12-16 at the Wayback Machine, Weapons and Field Gear of the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong, 1998.

- "The History Place — Vietnam War 1945–1960". Archived from the original on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- Turner, Robert F. (1990). "Myths and Realities in the Vietnam Debate". The Vietnam Debate: A Fresh Look at the Arguments. University Press of America. ISBN 9780819174161. Archived from the original on 2017-04-10. Retrieved 2017-06-05.

- Morris, Stephen J. (1999). Why Vietnam Invaded Cambodia: Political Culture and the Causes of War. Stanford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780804730495.

- SarDesai, D. R. (1968), Indian Foreign Policy in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, 1947-1964, Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 194

- Gardner, Lloyd C. and Gittinger, Ted, Eds. (2004), "The Search for Peace in Vietnam, 1964-1968," Bryan, TX: Texas A&M University Press, p. 194

Further reading

- Vu, Tuong (2010). Paths to Development in Asia: South Korea, Vietnam, China, and Indonesia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139489010.

External links

- Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam

- recorded sound of that declaration on YouTube

- video of this ceremony on YouTube

| Preceded by French Indochina Nguyễn dynasty |

Democratic Republic of Vietnam 1945–76 |

Succeeded by Socialist Republic of Vietnam |

.svg.png)