Climate change in Vietnam

Vietnam is considered, in coming decades, to be among the most affected countries by global climate change.[1] A large number of studies that Vietnam is experiencing climate change and will be severely negatively affected in coming decades. These negative effects include sea level rise, salinity intrusion and other hydrological problems like flood, river mouth evolution, sedimentation as well as the increasing frequency of natural hazards such as cold waves, storm surges will all exert negative effects on the country's development and economy including agriculture, aquaculture, road infrastructure, etc.

.jpg)

Some issues, such as land subsidence (caused by excessive groundwater extraction) further worsen some of the effects climate change will bring (sea level rise) especially in areas such as the Mekong Delta.[2] The government, NGOs, and citizens have taken various measures to mitigate and adapt to the impact.

Background

The increase in the concentration of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere has caused anthropogenic global climate change, which has drawn wide attention from the international community. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an intergovernmental organization affiliated with the United Nations, established in 1998 by the World Meteorological Organization and the United Nations Environment Programme, to study climate change caused by human activities.[3] The IPCC report (2014) believes that global climate change will have a major impact on a large number of countries, which is unfavorable for areas with poor adaptability and unusually fragile natural conditions. Unfortunately, Vietnam is identified by IPCC as one of the countries likely to be most affected by climate change (IPCC 1994, 2001)[4] due to its extensive coastline, vast deltas and floodplains, location on the path of typhoons as well as its large population in poverty.[5]

Projected effects

Through various observations and research methods, scholars generally believe that in the past historical period and the forecasting future model, over the whole territory of Vietnam, climate change signals have been identified through the changes in various observed climate elements. In sum, the temperature and the precipitation are generally presenting an increasing trend; the frequency of extreme values is rising. Moreover, the precipitation distribution of time and space is more uneven.

Temperature

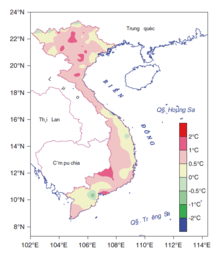

According to daily data collected from 23 coastal meteorological stations in Vietnam for the period from 1960 to 2011, during the 52 years (from 1960 to 2011), average annual temperatures in the coastal zones of Vietnam have increased significantly. High increases of 0.24℃ and 0.28℃ per decade are found at Vung Tau and Ca Mau stations, respectively, located in the South Coast. Most of the stations in the North- Central Coast show an increase of 0.15℃to 0.19℃ per decade. (Figure 1)[6]

Furthermore, changes in maximum temperature in Vietnam varied in the range from −3 °C to 3 °C. Changes in minimum temperatures mostly varied in the range from −5 °C to 5 °C. Both maximum and minimum temperatures have tended to increase, with minimum temperatures increasing faster than maximum temperatures, reflecting the trend of global climate warming.[7]

Precipitation

Unlike temperature, changes in rainfall trends vary significantly between regions. (Figure 2) Statistics of rainfall over Vietnam for the period from 1961 to 2008 show a significant increasing trend in the South-Central Coast while it has tended to decrease in the northern coast (from approximately 17N northward). Another indicator is the annual maximum 1-day precipitation (RX1day). During 1961 to 2008, there is an increasing trend of up to 14% per decade for RX1day, which means that the extreme value of rainfall has been mounting.[8]

Sea Level Rise, Extreme Weather and Others

One significant result is the sea level rise and seawater intrusion, with the coastline retreat, coastal erosion, salinity intrusion related to them. Also, scholars warn that other hydrological problems will emerge, such as flood, river mouth evolution, sedimentation. Frequency of tropical cyclones, storm surges, tsunami and other natural hazards will increase, too, to varying degrees.[9]

The water level monitored at Vietnam coastal gauges has shown that the pattern of changes in annual average sea level is different over the years (starting 1960). Almost all the stations have shown an increasing trend. (See Figure 3) Based on data collected from the monitoring stations the mean sea level rise along the Vietnamese coastal area is about 2.8 mm/ year during the period 1993–2008 (MONRE - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Vietnam, 2009).[10] According to these simulations, 37% of the total area of the Mekong Delta may be inundated to a depth of over 1 m under a sea level rise scenario of 0.5 m.[11]

The Southern Institute of Water Resources Research (SIWRR) reported the increasing trend of salinity intrusion. A large area of the Mekong Delta is seasonally affected by salinity intrusion during the dry season, especially during the months of March and April, when river flow is at its minimum. Considerable changes have been observed in the flow regime of the Mekong River, with a lower water flow at the beginning of the dry season, resulting in salinity intrusion starting earlier than usual.[12]

Other consequences are the increased frequency of extreme weather events. In the past 40 years, the number of typhoons in Vietnam has decreased, but the intensity has increased and the scope of damage has expanded. According to this scenario, the intensity and unpredictability of the typhoon will increase, and the scope of damage will continue to expand southward. In 2007 to 2008, the flooding in the central provinces exceeded that of past 48 years; the northern part of Vietnam encountered an unprecedented cold wave, lasting for 38 days, resulting in 30 million US dollars Crop and livestock losses.[13]

The impact on various Aspects

Vietnam's geography of long coastal areas and monsoon rains makes its land and people highly sensitive to the above-mentioned results such as elevations in sea levels and the intensification of weather extremes that climate change will bring.[15] While the magnitude and speed of such trends remains unclear, there is sufficient certainty in the range of likely effects. The most obvious and extensive impact is on economic growth, which could be observed in a number of sectors. Other impacts, for instance, on health are also increasing.

Agriculture

Agriculture still accounts for about a quarter of Vietnam's GDP and is the main livelihood of 60% of the population.[16] However, agriculture is one of the industries that are directly and adversely affected by climate change. The impact of climate change on agriculture is reflected in the problems of agricultural land, plants, livestock, their survival and development, water supply difficulties and natural disasters affecting agricultural production.

Changes in yields vary widely across crops, agroecological zones, and climate scenarios. For rice, the projected Dry scenario would lead to reductions in yields ranging from 12 percent in the Mekong River Delta to 24 percent in the Red River Delta.[17] Daily meteorological data at 19 representative locations over the recent 50 years (1959 to 2009) were collected to analyze Northern Vietnam' s climatic change and its effects on rice production. On one side, the rising temperature due to the increase in CO2 concentration will increase the rice planting area in Vietnam and prolong the growing season. It is very likely that the rice planting limit in northern Vietnam will move west and north, the area will expand and the multiple cropping index will increase. On the other side, the growth period of rice in winter and spring is sensitive to temperature. The development process is accelerated, the vegetative growth period is shortened, even early flowering occurs, which is not conducive to the yield.[18]

There would be more extensive inundation of crop land in the rainy season and increased saline intrusion in the dry season as a consequence of the combination of sea level rise and higher river flooding. For the Mekong River Delta, it is estimated that about 590,000 ha of rice area could be lost due to inundation and saline intrusion, which accounts for about 13 percent of today's rice production in the region.[19] Table 1 shows the potential impact of climate change without adaptation under alternative climate scenarios on production of six major crops or crop categories relative to a 2050 baseline.[20][21]

Aquaculture

Aquaculture, especially in the Mekong River Delta, is an important source of employment and rural income. It is estimated that some 2.8 million people are employed in the sector, while export revenue is expected to be about $2.8 billion in 2010. Higher temperatures, an increased frequency of storms, sea level rise, and other effects of climate change are likely to affect fish physiology and ecology as well as the operation of aquaculture. Some fish species, such as catfish, may grow more rapidly with higher temperatures but be more vulnerable to disease. Meanwhile, the main impacts of climate change on aquaculture seem likely to be a consequence of increased flooding and salinity.[22]

Other Impacts on Economy

The International Monetary Fund estimates that Vietnam's economic growth may fall by 10% in 2021 due to climate change. Vietnam's coastline is 3,200 kilometers long and 70 percent of its population lives in coastal areas and low‐lying deltas (GFDRR 2015).[23] Given the country's concentration of population and economic assets in exposed areas, the negative impact on industrial production and economic growth could be unimaginable. A 1-meter rise in sea level would partially inundate 11 percent of the population and 7 percent of agricultural land (World Bank and GFDRR 2011; GFDRR 2015).[24]

Also, extreme natural disasters has caused huge Vietnamese casualties and property damage. In the first half of 2016, water intrusion, heavy rainfall, and extremely cold weather resulted in 37 deaths and 108 injuries, disaster losses are estimated to be 757 million US dollars.[25]

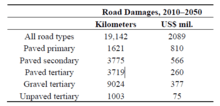

Moreover, current and future domestic infrastructure is influenced. For instance, the physical asset of road infrastructure, will be vulnerable to climate change impacts. Based on the existing road inventories and provincial allocations, one meter SLR would inundate, and hence destroy, 19,000 kilometers of roads in Vietnam, which is equivalent to 12 percent of existing road stocks. As reported in Table 2, rebuilding these damaged roads would cost approximately US$2.1 billion.[26]

Impacts on Health

Climate warming will directly or indirectly affect the spread of many infectious diseases, especially for the occurrence and spread of insect-borne diseases such as malaria, viral encephalitis and dengue. As the temperature of the sea surface rises, the incidence of disease transmitted through the water body will also increase. Tran Thi Giang Huong, Director of the Department of International Cooperation of the Ministry of Health of Vietnam, stated in 2017 that "from 2030 to 2050, climate change will cause, every year, 250,000 people's death from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea and heat shock" globally, according to the World Health Organization.[27]

Various responses

- Based on IPCC's classification, responses to deal with climate change could be generally classified into two genres: mitigation and adaptation. Climate change mitigation generally involves reductions in human (anthropogenic) emissions of greenhouse gases. Adaptation, in a broad sense, refers to all measures to respond to the existing and potential impacts, such as building seawalls to adapt to sea level rise, upgrading water reservoirs to adapt to flood and other water resource problems, etc.

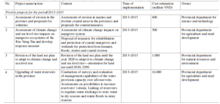

- The Vietnamese authorities have been responding to international initiatives to better understand and mitigate climate issues as well as putting large effort into adaptive measures. The country ratified the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1994 and ratified the “Kyoto Protocol” in 2002. According to the reporting obligations of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Vietnam issued the preliminary national initiative in December 2003, with the baseline lists of greenhouse gas emissions, mitigation options in the energy, forestry and agriculture sectors, and assessment of final adaptation measures (MONRE, 2003).[28] MONRE (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Vietnam) drafted the National Target Plan for Climate Change (NTP-RCC), which was approved in December 2008 by the Prime Minister's Decree (Vietnam Government, 2008). In 2015, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment issued the Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Climate Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation (Vietnam SREX),suggesting a series of measures to prevent extreme weather disasters.[29]

- Apart from NTP-RCC, Vietnam government has been cooperating with other countries and international organizations. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Vietnam is hosting 58 foreign programs and projects to assist Vietnam in tackling climate change, with a commitment of nearly US$430 million, including funding from World Bank, the Holland government and the Denmark government.[30] In recent years, international cooperation mechanisms involving climate issues emerges. The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism, is one mechanism between countries in the Mekong Basin (including China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam) to jointly enhance economic growth, poverty reduction, and, to deal with climate change and the water resources allocation associated with it.[31]

- In response to different impacts, the measures vary. In order to deal with the direct consequence of Sea Level Rise, the authority suggests measures including full protection: strengthening and elevating embankments nationwide; elevating houses above flood levels as well as withdrawal: “averts” sea-level rise impacts by leaving coastal areas and retreating inland.

- In terms of agriculture, the programmes by the government as well as local farmers could be roughly divided into three aspects:

* Short-term measures: Prevent soil erosion, implement soil protection, provide proactive crop irrigation, select crops suited to climate change, etc.

* Long-term measures: Adopt climate change-suited cropping patterns, create new species, modernize cultivation and stockbreeding techniques, etc.

* Management and harvesting practices: Redistribute regional crop and livestock production to better suit changing climate conditions, provide additional incentives for agriculture, forestry and aquafarming, etc.[32]

- Due to specific geographical conditions, local governments choose to carry programmes according to their own consideration under the framework of NTP-RCC. For instance, local government in Thanh Hoa Province and the Ba Ria-Vung Tau Province have released a large number of proposal and projects on upgrading of water reservoirs, revision of the landuse plan, and lectures and exhibitions to raise climate change awareness for all public servants, organizations, citizens. These measures are also divided into priority projects in the period 2013-2015, 2016-2020 according to the time schedule, and projects on groundwater resources, salinisation protection, natural disaster damage control, etc. according to different sectors.[33]

Different opinions

The development and the implementation of climate change response measures is very demanding and complicated because it involves several scientific disciplines, stakeholders and decision makers. In respect to responses to climate change in Vietnam, there are different voices, such as criticism on the authorities' measures, calls for more emphasis on farmers, women, etc. This is not only due to different methods the researchers adopted, different sources, for different purposes, and also due to the divergence exist in different regions, different geographical conditions, different political and economic statuses and relationship, different genders, etc.

Criticism of the Government's Response

Though the government has issued policies to limit greenhouse gas emissions, it is widely believed that it is difficult for Vietnam to achieve the target of mitigation.

Vietnam is one of the top 10 countries with the most serious air pollution in the world. The level of unsafe particles is similar to that of large cities and industrial areas in China. The International Monetary Fund reports that Vietnam's greenhouse gas emissions will triple by 2030, basically because of the dependence on fossil fuels for power generation.[35]

Coal currently accounts for 35% of the country's primary energy supply, higher than 15% in 2000. By 2035, Vietnam's coal demand is more likely to grow nearly 2.5 times. As little substitutes are adopted, the country will rely more on imported coal and it will be difficult to achieve the 8% reduction target by 2030.[36]

There are other critics on the government's climate change adaptive strategy. Some people believe that up to now government policies have focused on sector-wide assessments for the whole country and on “hard” adaptation measures—such as sea dikes, reinforced infrastructure, and durable buildings. Little attention has been paid to “soft” adaptation measures like increasing institutional capacity or the role of collective action and social capital in building resilience. Moreover, François Fortier (School of International Development and Global Studies, University of Ottawa) claims, in his essay, "Taking a climate chance: A procedural critique of Vietnam’s climate change strategy",[37] that the government's projects are partial and problematic in several ways. The first problem, according to Fortier, lies in the design of the process. It is mainly based on narrow analyses of the official information that "remain mostly blind to the power relations", which will necessarily shape climate change policy-making. Second, government's measures indeed increase poor citizen's vulnerability to climate change. He took the instance of the privatization of mangroves as the main reasons for the increase in long-term inequality in Xuan Thuy.[38] Then, this inequality is related to vulnerability, by directly concentrating human resources in the hands of fewer people, thereby limiting the right to use and dispose of assets under stressful strategies; and also by indirectly strengthening poverty and marginalization in local areas. Fortier concluded that the context of narrow political reforms and accumulation-intensifying capitalist delimits the possibilities and constraints of "the emerging stakes", objectives and processes of the Vietnamese government's climate change strategy.

According to François Fortier's analysis, Vietnam government's current adapting strategy therefore reflects and reinforces existing power relations in both politics and production. He believes that the national climate change strategy provides "an illusion of intervention and security", but actually largely fails to identify and mitigate the underlying causes of climate change, or to lay the ground for a mid-term and long-term adaptation strategy that can truly cope with "yet unknown levels of climatic and other structural changes."[39]

The Hidden Inequality between Different Groups Dealing with Climate Change

Due to the inequality in identity and economic and social status, the impact of climate change vary on different people. Also, due to natural conditions, the effect on regions vary in degrees. Regions such as the Mekong Delta are more vulnerable to climate change. Thus, in respond to the impacts, people in different regions tend to take different measures, in which process, the vulnerable group, especially the worst off, are often not able to equally enjoy the benefit of the government's policy, or might even be severely marginalized or impaired. One observation on adaptive measures comes from Le Dang, H. and Li, E., Nuberg, I. et al. In "Farmers’ assessments of private adaptive measures to climate change and influential factors: a study in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam"(2014), the authors collected data from structured interviews with 598 rice farmers in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. They argue that adapting to climate change in agriculture fundamentally depends on farmers' perceptions on climate change, their adaptive institutions and the effectiveness of adaptive measures.[40] Farmers in the Mekong Delta have different perceptions of climate change due to their knowledge, information resources, etc. Importantly, inappropriate adaptive decisions can result from misleading perceptions.

When farmers obtained the information of adaptive measures from their friends, relatives, neighbours or other sources (e.g. the Internet, pesticide companies and priests), this influenced their adaptation assessments. In contrast, there was no significant influence of information from public media and local authorities. (According to their research, only 11 of the 598 respondents obtained the information of adaptive measures from the Internet. ) Le Dang, H. and Li, E., Nuberg indicate that the sources and quality of information are particularly important and expect the improvement of both the accessibility and usefulness of local services. They believe that the improvement of farmers' knowledge about these matters should be the prior focus of the authorities in the Mekong Delta intending to promote adaptive behaviours.

Some scholars also suggest that if we look inside the family, gender inequality exists under the impact of climate change. Ashok K. Mishra and Valerian O. Pede, in their essay, "Perception of climate change and adaptation strategies in Vietnam: Are there intra-household gender differences?", argue that the socio-economic vulnerability of rural poor women is often entangled with the vulnerability of climate change; climate change often further expands their gender disadvantage.[41] The extreme weather caused by climate change, such as high temperatures, cold waves, and floods, increases the labor burden of women; infectious diseases due to warmer temperatures impair women's health. Since women are inherently at a disadvantage due to access to family and social resources, Ashok K. Mishra and Valerian O. Pede state that it is necessary to enhance women's awareness of climate change and promote the development of human resources. to organize environmental knowledge training and knowledge contests, moreover, to implement projects to improve women's disaster response capabilities.

As can be seen above, some people believe that the current policies and programmes have certain defects, ignoring the disadvantaged groups. Therefore, there are some voices arguing that adaptation options that reduce poverty and increase household resilience or that integrate climate change into development planning should be emphasized.

See also

External links

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE).http://www.monre.gov.vn/wps/portal/english

- Department of Meteorology, Hydrology and Climate Change (DMHCC).http://www.dmhcc.gov.vn/

- Department of Water Resource Management.http://dwrm.gov.vn/

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(IPCC).http://www.ipcc.ch/

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.https://unfccc.int/

- United Nations Environment Programme.http://web.unep.org/

- The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR).https://www.gfdrr.org/

- The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism. http://www.lmcchina.org/eng/.

References

- Sustainable Development Department, Vietnam Country Office, "The World Bank: Climate-Resilient Development in Vietnam: Strategic Directions for the World Bank", January 2011.

- Groundwater extraction, land subsidence, and sea-level rise in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(IPCC). http://www.ipcc.ch/

- IPCC: CLIMATE CHANGE 2014 Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability Summaries, Frequently Asked Questions, and Cross-Chapter Boxes, A Working Group II Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg2/WGIIAR5-IntegrationBrochure_FINAL.pdf Archived 2018-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, 2014.

- Nguyen Danh Thao, Hiroshi Takagi, Miguel Esteban. Coastal Disasters and Climate Change in Vietnam . Burlington : Elsevier Science, 2014.

- Schmidt-Thomé, Philipp; Nguyen, Thi Ha; Pham, Thanh Long. Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Vietnam: Development and Implementation. Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Nguyen Danh Thao, Hiroshi Takagi, Miguel Esteban. Coastal Disasters and Climate Change in Vietnam . Burlington : Elsevier Science, 2014.

- Schmidt-Thomé, Philipp; Nguyen, Thi Ha; Pham, Thanh Long. Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Vietnam: Development and Implementation. Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- Nguyen Danh Thao, Hiroshi Takagi, Miguel Esteban. Coastal Disasters and Climate Change in Vietnam . Burlington : Elsevier Science, 2014.

- ibid.

- Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change: 70272 Vietnam. Washington, DC. The World Bank Group. 2010.

- https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/ch/2639-The-threat-to-Vietnam-s-poor

- http://asean.zwbk.org/newsdetail/19365.html

- Nguyen Danh Thao, Hiroshi Takagi, Miguel Esteban. Coastal Disasters and Climate Change in Vietnam . Burlington : Elsevier Science, 2014.

- Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change: 70272 Vietnam. Washington, DC. The World Bank Group. 2010.

- YANG Wen-kan and L I Xiang-ge, "Climatic Change and Its Effect on Rice Yields in the North Vietnam", Journal of Nanjing Institute of Meteorology, Vol. 27, No.1, Feb.2015.

- ibid.

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE). http://www.dmhcc.gov.vn/ Archived 2018-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change: 70272 Vietnam. Washington, DC. The World Bank Group. 2010.

- ibid.

- The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) .2015.

- Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change: 70272 Vietnam. Washington, DC. The World Bank Group. 2010.

- Alan Boyd. "Climate change refugees imperil Vietnam’s growth" JANUARY 11, 2018. Asia Times. http://www.atimes.com/article/climate-change-refugees-imperil-vietnams-growth/

- Paul S. Chinowsky, Amy E. Schweikert, Niko Strzepek and Kenneth Strzepek. "Road Infrastructure and Climate Change in Vietnam", Sustainability, July, 2015. ISSN 2071-1050.

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

- Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change: 70272 Vietnam. Washington, DC. The World Bank Group. 2010.

- Thu Thi Nguyen & Jamie Pittock&Bich Huong Nguyen, "Integration of ecosystem-based adaptation to climate change policies in Viet Nam". Climate Change. Feb.2017.

- VOV5.vn. "Vietnam Strengthens International Cooperation to Address Climate Change", http://vovworld.vn/zh-CN/%E6%97%B6%E4%BA%8B%E8%AF%84%E8%AE%BA/%E8%B6%8A%E5%8D%97%E5%8A%A0%E5%BC%BA%E5%9B%BD%E9%99%85%E5%90%88%E4%BD%9C%E5%BA%94%E5%AF%B9%E6%B0%94%E5%80%99%E5%8F%98%E5%8C%96-247776.vov

- The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism. http://www.lmcchina.org/eng/.

- Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change: 70272 Vietnam. Washington, DC. The World Bank Group. 2010.

- Schmidt-Thomé, Philipp; Nguyen, Thi Ha; Pham, Thanh Long. Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Vietnam: Development and Implementation. Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- ibid.

- Alan Boyd. "Climate change refugees imperil Vietnam’s growth" JANUARY 11, 2018. Asia Times. http://www.atimes.com/article/climate-change-refugees-imperil-vietnams-growth/.

- ibid.

- François Fortier, "Taking a climate chance: A procedural critique of Vietnam’s climate change strategy", Asia Pacific Viewpoint, Vol. 51, No. 3, December 2010, pp229–247.

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Le Dang, H., Li, E., Nuberg, I. et al. "Farmers’ assessments of private adaptive measures to climate change and influential factors: a study in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam", Nat Hazards, Volume 71, Issue 1, pp 385–401, 2014.

- Ashok K. Mishra and Valerian O. Pede, "Perception of climate change and adaptation strategies in Vietnam: Are there intra-household gender differences?". International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management. Vol. 9 No. 4, 2017. pp. 501-516.