Vietnamese cash

Vietnamese cash (Chinese: 文錢 văn tiền; chữ Nôm: 銅錢 đồng tiền; French: sapèque)[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] is a cast round coin with a square hole that was an official currency of Vietnam from the Đinh dynasty in 970 until the Nguyễn dynasty in 1945, and remained in circulation in North Vietnam until 1948. The same type of currency circulated in China, Japan, Korea, and Ryūkyū for centuries. Though the majority of Vietnamese cash coins throughout history were copper coins, lead, iron (from 1528) and zinc (from 1740) coins also circulated alongside them often at fluctuating rates (with 1 copper cash being worth 10 zinc cash in 1882).[7] The reason why coins made from metals of lower intrinsic value were introduced was because of various superstitions involving Vietnamese people burying cash coins, as the problem of people burying cash coins became too much for the government as almost all coins issued by government mints tended to be buried mere months after they had entered circulation, the Vietnamese government began issuing coins made from an alloy of zinc, lead, and tin. As these cash coins tended to be very fragile they would decompose faster if buried which caused the Vietnamese people to stop burying their coins.[8][9]

| Vietnamese cash | |

|---|---|

| Hán-Việt: 文 (Văn) Chữ Nôm: 銅 (Đồng) French: Sapèque | |

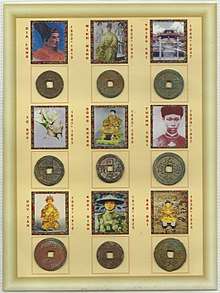

_970%E2%80%93979_%26_B%E1%BA%A3o_%C4%90%E1%BA%A1i_Th%C3%B4ng_B%E1%BA%A3o_(%E4%BF%9D%E5%A4%A7%E9%80%9A%E5%AF%B6)_1933%E2%80%931945_01.jpg) First and last Vietnamese cash coins: Thái Bình Hưng Bảo (太平興寶) issued during the Đinh dynasty. Bảo Đại Thông Bảo (保大通寶) issued under Bảo Đại (1925–1945). | |

| Denominations | |

| Superunit | |

| 10 | Phân (分) |

| 36–60 | Mạch (陌) / Tiền (錢) |

| 360–600 | Quán (貫) / Nguyên (元)[1][2][3] |

| 20 | Đồng (銅) In the Democratic Republic of Vietnam between 1947 and 1948, making them equal to 5 xu (樞). |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 970 |

| User(s) | |

This infobox shows the latest status before this currency was rendered obsolete. | |

Currency units

Traditionally, the basic units of Vietnamese currency were quan (貫, quán), tiền, and đồng. One quan was 10 tiền, and one tiền was between 50 and 100 đồng, depending on the time period. From the reign of Emperor Trần Thái Tông onward, 1 tiền was 69 đồng in ordinary commercial transactions but 1 tiền was 70 đồng for official transactions. From the reign of Emperor Lê Lợi, 1 tiền was decreed to be 50 đồng. During the Southern and Northern Dynasties of Vietnam period, beginning in 1528, coins were reduced from 24 millimetres (0.94 in) to 23 millimetres (0.91 in) in diameter and diluted with zinc and iron. The smaller coinage was called tiền gián or sử tiền, in contrast to the larger tiền quý (literally, "valuable cash") or cổ tiền. One quan tiền quý was equivalent to 600 đồng, while 1 quan tiền gián was only 360 đồng.[10] During the Later Lê Dynasty, 1 tiền was 60 đồng; therefore, 600 đồng was 1 quan. During the Yuan Dynasty, Vietnamese traders at the border with China used the rate 1 tiền to 67 đồng. Zinc coins began to appear in Dai Viet during the 18th century. One copper (đồng) coin was worth 3 zinc (kẽm) coins. Beginning with the reign of Emperor Gia Long, both copper and zinc coins were in use. Originally the two coins had equal value, but eventually a copper coin rose to double the worth of a zinc coin, then triple, then sixfold, until the reign of Emperor Thành Thái, it was worth ten times a zinc coin.

History

Đinh and Early Lê dynasties

The first Vietnamese coins were cast under the rule of the Đinh Dynasty (968–981) with the introduction of the Thái Bình Hưng Bảo (太平興寶) under Đinh Bộ Lĩnh.[11] Though for the next 2 centuries coins would remain a rarity in the daily lives of the common people as barter would remain the dominant means of exchange under both the Đinh and Early Lê dynasties.[12]

Lý dynasty

Generally cast coins produced by the Vietnamese from the reign of Lý Thái Tông and onwards were of diminutive quality compared to the Chinese variants,[13] they were often produced with inferior metallic compositions and made to be thinner and lighter than the Chinese wén due to a severe lack of copper that existed during the Lý dynasty.[14] This inspired Chinese traders to recast Chinese coins for export to Vietnam which caused an abundance of coinage to circulate in the country prompting the Lý government to suspend the mintage of coins for 5 decades.[14]

Trần dynasty

The production of inferior coinage continued under the Trần dynasty.[15] It was under the reign of Trần Dụ Tông that the most cash coins were cast of this period, this was because of several calamities such as failed crops that plagued the country during his reign that caused the Trần government to issue more coins to the populace as compensation.[15] The internal political struggles of the Trần ensured the cessation of the production of coinage and as such no coins were produced during the entire reigns of the last 7 monarchs of the Trần dynasty.[15]

Hồ dynasty

_-_%C4%90%E1%BA%A1i_Tr%E1%BA%A7n_Th%C3%B4ng_B%E1%BA%A3o_H%E1%BB%99i_Sao_(%E9%88%94%E6%9C%83%E5%AF%B6%E9%80%9A%E9%99%B3%E5%A4%A7)_Replica_-_Howard_A._Daniel_III.jpg)

During the Hồ dynasty the usage of coins was banned by Hồ Quý Ly in 1396 in favour of the Thông Bảo Hội Sao (通寶會鈔) banknote series and ordered people to exchange their coinage for these banknotes (with an exchange rate of 1 Quân of copper coins for 2 Thông Bảo Hội Sao banknotes),[16] those who denied to exchange or continued to pay with coins would be executed and have their possessions taken by the government. Despite these harsh laws very few people actually preferred paper money and coins remained widespread in circulation forcing the Hồ dynasty to retract their policies.[17][18][19] The Thông Bảo Hội Sao banknotes of the Hồ dynasty featured designs with seaweed, patterns of waves, clouds, and turtles on them.[20] Under the Hồ dynasty Thánh Nguyên Thông Bảo (聖元通寶), and Thiệu Nguyên Thông Bảo (紹元通寶) but they would only be manufactured in small numbers, though the Later Lê dynasty would produce coins with the same inscriptions less than half a century later in larger quantities.[21][22]

Later Lê, Mạc, and Revival Lê dynasties

After Lê Thái Tổ came to power in 1428 by ousting out the Ming dynasty ending the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam, Lê Thái Tổ enacted new policies to improve the quality of the manufacturing of coinage leading to the production of coins with both excellent craftsmanship and metal compositions that rivaled that of the best contemporary Chinese coinage.[23]

Between 1633 and 1637 the Dutch East India Company sold 105,835 strings of 960 cash coins (or 101,600,640 văn) to the Nguyễn lords in Vĩnh Lạc Thông Bảo (永樂通寶), and Khoan Vĩnh Thông Bảo (寬永通寶) coins. This was because the Japanese had restricted trade forcing the Southern Vietnamese traders to purchase its copper coins from the Dutch Republic rather than from Japanese merchants as had happened earlier. This trade lead to a surplus of copper in the territory of the Nguyễn lords allowing them to use the metal (which at the time was scarce in the north) for more practical applications such as nails and door hinges.[24][25][26] After this Nagasaki trade coins which were specifically minted for the Vietnamese market, also started being traded and to circulate in the northern parts of Vietnam where the smaller coins would often be melted down for utensils and only circulated in Hanoi while larger Nagasaki trade coins circulated all over Vietnam.

From the Dương Hòa era (1635–1643) under Lê Thần Tông until 1675 no coins were cast due to the political turmoil, at the turn of the 18th century Lê Dụ Tông opened a lot of copper mines and renewed the production of high quality coinage. From 1719 the production of cast copper coins had ceased for 2 decades and taxes were more heavily lifted on the Chinese population as Mandarins could receive a promotion in rank for every 600 strings of cash (or 600,000 coins). Under Lê Hiển Tông a large variety of "Cảnh Hưng" (景興) coins were cast with varying descriptions on the obverse,[27] in fact it is thought that more variations of the "Cảnh Hưng" coin exist than of any other Oriental cash coin in history.[28] And there were new large Cảnh Hưng coins with denominations of 50 and 100 văn introduced. And from 1740 various provincial mint marks were added on the reverses of coins. Currently there are around 80 known different kinds of "Cảnh Hưng" coins, the reason for this diversity is because the Lê government was in dire need for coins to pay for its expenditures, while it needed to collect more taxes in coins so it began to mint a lot of coins, later to fulfill this need the Lê legalised the previously detrimental workshops that were minting inferior coins in 1760 in order to meet the market's high demand for coinage, this backfired as the people found the huge variety in quality and quantity confusing.[29]

Tây Sơn dynasty

Under Nguyễn Nhạc the description of Thất Phân (七分) was first added to the reverses of some coins indicating their weight, this continued under the Nguyễn dynasty.[30] Under the reign of Nguyễn Huệ Quang Trung Thông Bảo (光中通寶) cash coins were produced made in two different types of metal, one series of copper and one series of tin, as well as alloys between the two or copper coins of red copper.[30]

Nguyễn dynasty

Pre-colonial era

Under Gia Long three kinds of cash coins were produced in smaller denominations made of copper, lead, and zinc.[31] From 1837 under the reign of Minh Mạng 1 Mạch (陌) brass cash coins were issued, these cash coins feature Minh Mạng Thông Bảo (明命通寶) on their obverses but have 8 characters on their reverses. 1 Mạch coins would be continued under subsequent rulers of the Nguyễn dynasty.[31]

-_Th%E1%BA%A5t_Ph%C3%A2n_(%E4%B8%83%E5%88%86)_copper_and_zinc_01.jpg)

Since the reign of Gia Long zinc coins had replaced the usage of copper and brass coins and formed the basis of the Vietnamese currency system.[31] Under Gia Long the standard 1 văn denomination coins weighed 7 phần, under Minh Mạng 6 phần (approximately 2,28 Grams) which would remain the standard for future rulers.[31] Zinc cash coins produced in Hanoi under Tự Đức had the mint mark "Hà Nội" (何內) on them, with there being another mint in Sơn Tây (山西).[32]

However, in 1871 the production of zinc cash coins stopped as many mines were being blocked by Chinese pirates, and the continued production of these coins would be too expensive.[31] Other reasons for the discontinuation of zinc cash coins despite them being indispensable to the general populace was because they were heavy compared to its nominal value and the metal is quite brittle.[31] To the French zinc coinage also presented a huge in inconvenience since their colonisation of Cochinchina in 1859 as the exchange between French francs and zinc văn meant that a large amount of zinc coins were exchanged for the French franc.[31] Zinc cash coins often broke during transportation as the strings that kept them together would often snap the coins would fall on the ground and a great number of them would break into pieces, and these coins were also less resistant to oxidation causing them to corrode faster than other coinages.[31]

- J. Silvestre, Monnaies et de Médailles de l'Annam et de la Cochinchine Française (1883).

Prior to 1849 brass coins had become an extreme rarity and only circulated in the provinces surrounding the capital cities of Vietnam, but under Tự Đức new regulations and (uniform) standards for copper cash coins were created to help promote their usage.[31] Between 1868 and 1872 brass coins were only around 50% copper, and 50% zinc.[31] Due to the natural scarcity of copper in Vietnam the country always lacked the resources to produce sufficient copper coinage for circulation.[31]

Under Tự Đức large coins with the denomination of 60 văn were introduced, these coins were ordered to circulate at a value of 1 tiền, but their intrinsic value was significantly lower so they were badly received and the production of these coins was quickly discontinued in favour of 20, 30, 40, and 50 văn coins known as Đồng Sao. In 1870 Tự Đức Bảo Sao cash coins of 2, 3, 8, and 9 Mạch were issued.[31] Large denomination coins were mostly used for tax collection as their relatively low intrinsic value lowered their spending power on the market.[33][34]

List of large denomination cash coins issued under Emperor Tự Đức:[35][36]

| Denomination | Hán tự (reverse inscription) | Years of mintage | Weight | Toda image | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 văn | 準十文 | 1861 | 5.66 g. | None | |

| 10 văn | 準文一十 | 1870 | 5.66 g. | None | |

| 20 văn | 準文二十 | 1861–1870 | 11.33 g. | None | |

| 30 văn | 準文三十 | 1861–1870 | None | ||

| 40 văn | 準文四十 | 1870 | 12.20 g. | None | |

| 50 văn | 準文五十 | 1861 | 23.40 g. | ||

| 50 văn | 準文五十 | 1870 | 12.75 g. | _-_Art-Hanoi_02.jpg) | |

| 60 văn | 準文六十 | 1870 | 12.20 g. | ||

| 2 mạch (120 văn) | 準當二陌 | 1870 | 20.52 g. | None | |

| 3 mạch (180 văn) | 準當三陌 | 1870 | None | ||

| 8 mạch (480 văn) | 準當八陌 | 1870 | None | ||

| 9 mạch (540 văn) | 準當九陌 | 1870 | 28.03 g. | None | |

| 1 quán | 準當一貫 | 1870 | 32.96 g. | None |

In 1882 at the time when Toda's Annam and its minor currency was published only 2 government mints remained in operation, one in Hanoi, and one in Huế.[7] Though private mints were allowed to cast cash coins with the permission of the government, and a large number of cash coins were also imported from abroad as at that time the Portuguese colony of Macau had 6 mints with 12 furnaces producing 600,000 cash coins for Vietnam on a daily basis.[7]

Cash coins circulated in the 19th century along with silver and gold bars, as well as silver and gold coins known as tiền.[31] Denominations up to 10 tiền were minted, with the 7 tiền coins in gold and silver being similar in size and weight to the Spanish 8 real and 8 escudo pieces.[31] These coins continued to be minted into the 20th century, albeit increasingly supplanted by French colonial coinage.[31]

Under French rule

After the introduction of modern coinage by the French in 1878, cash coins remained in general circulation in French Cochinchina.[37] Despite the later introduction of the French Indochinese piastre, zinc and copper-alloy cash coins would continue to circulate among the Vietnamese populace throughout the country as the primary form of coinage as the majority of the population lived in extreme poverty until 1945 (and 1948 in some areas) and were valued at the rates of about 500–600 cash coins for one piastre.[38] The need for coins was only a minor part in the lives of most Vietnamese people at the time as barter remained more common as all coins were bartered on the market according to their current intrinsic values.[38]

Initially the French attempted to supplement cash coins in circulation by punching round holes into French 1 centime coins and shipping a large amount of them to French Cochinchina, but these coins did not see much circulation and the Cochinchinese people largely rejected them.[39]

On 7 April & 22 April 1879 the governor of French Cochinchina had decreed that the new designs for coins with "Cochinchine Française" on them would be accepted with the denominations 2 sapèques (cash coins), 1 cent, 10 cents, 20 cents, 50 cents, and the piastre.[40] All coins except for the piastre was allowed to be issued, which allowed for Spanish dollars and Mexican reals to continue circulating.[40] The Paris Mint produced the new machine-struck 2 sapèques "Cochinchine Française" cash coins.[40] These French produced bronze cash coins weighed 2 grams were valued at 1⁄500 piastre, they saw considerably more circulation than the previous French attempt at creating cash coins, but were still largely disliked by the Cochinchinese people.[40] The local population still preferred their own Tự Đức Thông Bảo (嗣德通寶) cash coin despite it being only valued at 1⁄1000 piastre.[40]

Following the establishment of French Indochina, a new version of the French 2 sapèques was produced from 1887 to 1902 which was also valued at 1⁄500 piastre and were likely forced on the Vietnamese people when they were paid for their goods and/or services by the French as the preference still was for indigenous cash coins.[40]

Under French administration the Nguyễn government issued the Kiến Phúc Thông Bảo (建福通寶), Hàm Nghi Thông Bảo (咸宜通寶), Đồng Khánh Thông Bảo (同慶通寶), Thành Thái Thông Bảo (成泰通寶), Duy Tân Thông Bảo (維新通寶) cash coins of different metal compositions and weights.[41] Each of these cash coins had their own value against the French Indochinese piastre.[41] Because the exchange values between the native cash coins and silver piasters were confusing, the local Vietnamese people were often cheated by the money changers during this period.[41]

On 1 August 1898 it was reported in the Bulletin Economique De L’Indo-Chine article; Le Monnaie De L’Annam that the Huế Mint was closed in the year 1887, and in the year 1894, the casting of cash coins had started at the Thanh Hóa Mint.[41] Between the years 1889 and 1890 the Huế Mint produced 1321 strings of 600 small brass Thành Thái Thông Bảo cash coins.[42] These small brass cash coins were valued at 6 zinc cash coins.[42] In the year 1893, large brass Thành Thái Thông Bảo cash coins with a denomination of 10 văn (十文, thập văn), or 10 zinc cash coins, started being produced by the Huế Mint.[42] The production of Thành Thái Thông Bảo cash coins were resumed at the Thanh Hóa Mint between the years 1894 and 1899.[42] Under Emperor Thành Thái gold and silver coinages were also produced.[42]

In the year 1902 the French ceased production of machine-struck cash coins at the Paris Mint and completely deferred the production of cash coins back to the government of the Nguyễn dynasty.[41] There were people in Hanoi and Saigon that still preferred the French machine-struck cash coins, so a committee was set up in Hanoi that created a machine-struck zinc cash coin valued at 1⁄600 piastre dated 1905 but issued in 1906.[41] However, this series of cash coins wasn't well received by the either the local or the French population as the coins were brittle, prone to corrosion, and easily broke so their production was quickly halted.[41]

The last monarch whose name was cast on cash coins, Emperor Bảo Đại, died in 1997.

Democratic Republic of Vietnam

After the Democratic Republic of Vietnam declared their independence in 1945 they began issuing their own money, but cash coins continued to circulate in the remote areas of Bắc Bộ and Trung Bộ where there was a lack of xu, hào, and đồng coins for the population. The Democratic Republic of Viet Nam Decree 51/SL of January 6, 1947 officially set the exchange rate at 20 Vietnamese cash coins for 1 North Vietnamese đồng making them equal to 5 xu each. Vietnamese cash coins continued to officially circulate in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam until April 13, 1948.[39]

Aftermath

During the Vietnam War a large number or Vietnamese numismatic charms with both authentic as well as fantasy coin inscriptions were produced in South Vietnam to be sold to foreigners interested in collecting Vietnamese antiques.[43] These fantasy inscriptions included legends like Quang Trung Trọng Bảo (光中重寶),[44] Hàm Nghi Trọng Bảo (咸宜重寶),[45] and Khải Định Trọng Bảo (啓定重寶),[46] the latter of which being based on the Khải Định Thông Bảo (啓定通寶).

List of Vietnamese cash coins

During the almost 1000 years that Vietnamese copper cash coins were produced, they often significantly changed quality, alloy, size, and workmanship. In general, the coins bear the era name(s) of the monarch (Niên hiệu/年號) but may also be inscribed with mint marks, denominations, miscellaneous characters, and decorations.

Unlike Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Ryūkyūan cash coins that always have the inscription in only one typeface, Vietnamese cash coins tend to be more idiosyncratic bearing sometimes Regular script, Seal script, and even Running script on the same coins for different characters, and it's not uncommon for one coin to be cast almost entirely in one typeface but has an odd character in another. Though early Vietnamese coins often bore the calligraphic style of the Chinese Khai Nguyên Thông Bảo (開元通寶) coin, especially those from the Đinh until the Trần dynasties.[47]

The following coins were produced to circulate in Vietnam:

Green text indicates that this cash coin has been recovered in modern times but is not mentioned in any historical chronicles.

Blue text indicates that the cash coin has its own article on Wikipedia.[lower-alpha 3]

(中) indicates that there exists a Chinese, Khitan, Tangut, Jurchen, Mongol, and/or Manchu cash coin (including rebel coinages) with the same legend as the Vietnamese cash coin.

Further reading: List of Chinese cash coins by inscription.

Fuchsia text = Indicates that this is a misattributed cash coin (these cash coins were noted by historical sources or standard catalogues but later turned out to be misattributed).

Gold text Indicates that this is a fake or fantasy referenced by Eduardo Toda y Güell in his Annam and its Minor Currency (pdf), the possible existence of these cash coins have not been verified by any later works.| Inscription (chữ Quốc ngữ) | Inscription (Hán tự) | Years of mintage | Dynasty | Monarch(s) | Toda image | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thái Bình Hưng Bảo[lower-alpha 4] | 太平興寶 | 970–979 | Đinh (丁) | Đinh Tiên Hoàng (丁先皇) Đinh Phế Đế (丁廢帝) | ||

| Thiên Phúc Trấn Bảo | 天福鎮寶 | 986 | Early Lê (前黎) | Lê Hoàn (黎桓) | ||

| Lê | 黎 | 986 | Early Lê (前黎) | Lê Hoàn (黎桓) | None | |

| Thuận Thiên Đại Bảo | 順天大寶 | 1010–1028 | Lý (李) | Lý Thái Tổ (李太祖) | ||

| Càn Phù Nguyên Bảo | 乾符元寶 | 1039–1041 | Lý (李) | Lý Thái Tông (李太宗) | _at_room_4_Ly_Dynasty_(11th_-_13th_c.)_of_the_Museum_of_Vietnamese_History.jpg) | |

| Minh Đạo Nguyên Bảo (中) | 明道元寶 | 1042–1043 | Lý (李) | Lý Thái Tông (李太宗) | None | _at_room_4_Ly_Dynasty_(11th_-_13th_c.)_of_the_Museum_of_Vietnamese_History.jpg) |

| Thiên Phù Thông Bảo[lower-alpha 5] | 天符通寶 | 1120–1127 | Lý (李) | Lý Nhân Tông (李仁宗) | None | _at_room_4_Ly_Dynasty_(11th_-_13th_c.)_of_the_Museum_of_Vietnamese_History.jpg) |

| Thiên Phù Nguyên Bảo[lower-alpha 6] | 天符元寶 | 1120–1127 | Lý (李) | Lý Nhân Tông (李仁宗) | None | |

| Đại Định Thông Bảo (中) | 大定通寶 | 1140–1162 | Lý (李) | Lý Anh Tông (李英宗) | ||

| Thiên Cảm Thông Bảo | 天感通寶 | 1044–1048 | Lý (李) | Lý Anh Tông (李英宗) | None | |

| Thiên Cảm Nguyên Bảo | 天感元寶 | 1174–1175 | Lý (李) | Lý Anh Tông (李英宗) | None | |

| Chính Long Nguyên Bảo | 正隆元寶 | 1174–1175 | Lý (李) | Lý Anh Tông (李英宗) | None | _at_room_4_Ly_Dynasty_(11th_-_13th_c.)_of_the_Museum_of_Vietnamese_History1.jpg) |

| Thiên Tư Thông Bảo | 天資通寶 | 1202–1204 | Lý (李) | Lý Cao Tông (李高宗) | None | |

| Thiên Tư Nguyên Bảo | 天資元寶 | 1202–1204 | Lý (李) | Lý Cao Tông (李高宗) | None | |

| Trị Bình Thông Bảo (中)[lower-alpha 7] | 治平通寶 | 1205–1210 | Lý (李) | Lý Cao Tông (李高宗) | None | |

| Trị Bình Nguyên Bảo | 治平元寶 | 1205–1210 | Lý (李) | Lý Cao Tông (李高宗) | _at_room_4_Ly_Dynasty_(11th_-_13th_c.)_of_the_Museum_of_Vietnamese_History3.jpg) | |

| Hàm Bình Nguyên Bảo[48] (中)[lower-alpha 8] | 咸平元寶 | 1205–1210 | Lý (李) | Lý Cao Tông (李高宗) | None |  |

| Kiến Trung Thông Bảo (中) | 建中通寶 | 1225–1237 | Trần (陳) | Trần Thái Tông (陳太宗) | None | |

| Trần Nguyên Thông Bảo | 陳元通寶 | 1225–1237 | Trần (陳) | Trần Thái Tông (陳太宗) | None | |

| Chính Bình Thông Bảo | 政平通寶 | 1238–1350 | Trần (陳) | Trần Thái Tông (陳太宗) | None | |

| Nguyên Phong Thông Bảo (中) | 元豐通寶 | 1251–1258 | Trần (陳) | Trần Thái Tông (陳太宗) | ||

| Thiệu Long Thông Bảo | 紹隆通寶 | 1258–1272 | Trần (陳) | Trần Thánh Tông (陳聖宗) | None | |

| Hoàng Trần Thông Bảo | 皇陳通寶 | 1258–1278 | Trần (陳) | Trần Thánh Tông (陳聖宗) | None | |

| Hoàng Trần Nguyên Bảo | 皇陳元寶 | 1258–1278 | Trần (陳) | Trần Thánh Tông (陳聖宗) | None | |

| Khai Thái Nguyên Bảo | 開太元寶 | 1324–1329 | Trần (陳) | Trần Minh Tông (陳明宗) | None | |

| Thiệu Phong Bình Bảo | 紹豐平寶 | 1341–1357 | Trần (陳) | Trần Dụ Tông (陳裕宗) | ||

| Thiệu Phong Nguyên Bảo | 紹豐元寶 | 1341–1357 | Trần (陳) | Trần Dụ Tông (陳裕宗) | ||

| Đại Trị Thông Bảo | 大治通寶 | 1358–1369 | Trần (陳) | Trần Dụ Tông (陳裕宗) |  | |

| Đại Trị Nguyên Bảo | 大治元寶 | 1358–1369 | Trần (陳) | Trần Dụ Tông (陳裕宗) | ||

| Cảm Thiệu Nguyên Bảo | 感紹元寶 | 1368–1370 | Trần (陳) | Hôn Đức Công (昏德公) | ||

| Cảm Thiệu Nguyên Bảo | 感紹元宝 | 1368–1370 | Trần (陳) | Hôn Đức Công (昏德公) | ||

| Đại Định Thông Bảo (中) | 大定通寶 | 1368–1370 | Trần (陳) | Hôn Đức Công (昏德公) | None | |

| Thiệu Khánh Thông Bảo | 紹慶通寶 | 1370–1372 | Trần (陳) | Trần Nghệ Tông (陳藝宗) | None | |

| Xương Phù Thông Bảo | 昌符通寶 | 1377–1388 | Trần (陳) | Trần Phế Đế (陳廢帝) | None | |

| Hi Nguyên Thông Bảo[lower-alpha 9] | 熙元通寶 | 1381–1382 | None | Nguyễn Hi Nguyên (阮熙元) | ||

| Thiên Thánh Nguyên Bảo | 天聖元寶 | 1391–1392 | None | Sử Thiên Thánh (使天聖) | ||

| Thánh Nguyên Thông Bảo | 聖元通寶 | 1400 | Hồ (胡) | Hồ Quý Ly (胡季犛) | ||

| Thiệu Nguyên Thông Bảo[lower-alpha 10] | 紹元通寶 | 1401–1402 | Hồ (胡) | Hồ Hán Thương (胡漢蒼) | ||

| Hán Nguyên Thông Bảo (中)[lower-alpha 11] | 漢元通寶 | 1401–1407 | Hồ (胡) | Hồ Hán Thương (胡漢蒼) | ||

| Hán Nguyên Thánh Bảo | 漢元聖寶 | 1401–1407 | Hồ (胡) | Hồ Hán Thương (胡漢蒼) | ||

| Thiên Bình Thông Bảo[lower-alpha 12] | 天平通寶 | 1405–1406 | None | Thiên Bình (天平) | ||

| Vĩnh Ninh Thông Bảo | 永寧通寶 | 1420 | None | Lộc Bình Vương (羅平王) | ||

| Giao Chỉ Thông Bảo[lower-alpha 13] | 交趾通寶 | 1419 | Minh (明) | Vĩnh Lạc Emperor (永樂帝) | None | |

| Vĩnh Thiên Thông Bảo | 永天通寶 | 1420 | None | Lê Ngạ (黎餓) | ||

| Thiên Khánh Thông Bảo (中) | 天慶通寶 | 1426–1428 | Later Trần (後陳) | Thiên Khánh Đế (天慶帝) | None | |

| An Pháp Nguyên Bảo | 安法元寶 | Rebellion[lower-alpha 14] | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Lợi (黎利) | ||

| Chánh Pháp Nguyên Bảo[lower-alpha 15] | 正法元寶 | Rebellion | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Lợi (黎利) | ||

| Trị Thánh Nguyên Bảo[lower-alpha 16] | 治聖元寶 | Rebellion | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Lợi (黎利) | ||

| Trị Thánh Bình Bảo[lower-alpha 17] | 治聖平寶 | Rebellion | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Lợi (黎利) |  | |

| Thái Pháp Bình Bảo | 太法平寶 | Rebellion | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Lợi (黎利) | None | |

| Thánh Quan Thông Bảo[lower-alpha 18] | 聖宮通寶 | Rebellion | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Lợi (黎利) | ||

| Thuận Thiên Thông Bảo | 順天通寶 | 1428–1433 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Thái Tổ (黎太祖) | None | |

| Thuận Thiên Nguyên Bảo (中) | 順天元寶 | 1428–1433 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Thái Tổ (黎太祖) | ||

| Thiệu Bình Thông Bảo | 紹平通寶 | 1434–1440 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Thái Tông (黎太宗) | _-_Scott_Semans_02.jpg) | |

| Đại Bảo Thông Bảo | 大寶通寶 | 1440–1442 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Thái Tông (黎太宗) | ||

| Thái Hòa Thông Bảo[lower-alpha 19] | 太和通寶 | 1443–1453 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Nhân Tông (黎仁宗) | ||

| Diên Ninh Thông Bảo | 延寧通寶 | 1454–1459 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Nhân Tông (黎仁宗) | ||

| Thiên Hưng Thông Bảo | 天興通寶 | 1459–1460 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Nghi Dân (黎宜民) |  | |

| Quang Thuận Thông Bảo | 光順通寶 | 1460–1469 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Thánh Tông (黎聖宗) | ||

| Hồng Đức Thông Bảo | 洪德通寶 | 1470–1497 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Thánh Tông (黎聖宗) | ||

| Cảnh Thống Thông Bảo | 景統通寶 | 1497–1504 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Hiến Tông (黎憲宗) | ||

| Đoan Khánh Thông Bảo | 端慶通寶 | 1505–1509 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Uy Mục (黎威穆) |  | |

| Giao Trị Thông Bảo | 交治通寶 | 1509 | None | Cẩm Giang Vương (錦江王) | ||

| Thái Bình Thông Bảo | 太平通寶 | 1509 | None | Cẩm Giang Vương (錦江王) | ||

| Thái Bình Thánh Bảo | 太平聖寶 | 1509 | None | Cẩm Giang Vương (錦江王) | ||

| Hồng Thuận Thông Bảo | 洪順通寶 | 1510–1516 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Tương Dực (黎襄翼) | ||

| Trần Tuân Công Bảo | 陳新公寶 | 1511–1512 | None | Trần Tuân (陳珣) | ||

| Quang Thiệu Thông Bảo | 光紹通寶 | 1516–1522 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Chiêu Tông (黎昭宗) | ||

| Trần Công Tân Bảo | 陳公新寶 | 1516–1521 | None | Trần Cao (陳暠) | None | |

| Thiên Ứng Thông Bảo | 天應通寶 | 1516–1521 | None | Trần Cao (陳暠) | ||

| Phật Pháp Tăng Bảo | 佛法僧寶 | 1516–1521 | None | Trần Cao (陳暠) | None | |

| Tuyên Hựu Hòa Bảo | 宣祐和寶 | 1516–1521 | None | Trần Cao (陳暠) | None | |

| Thống Nguyên Thông Bảo | 統元通寶 | 1522–1527 | Later Lê (後黎) | Lê Cung Hoàng (黎恭皇) | ||

| Minh Đức Thông Bảo | 明德通寶 | 1527–1530 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Thái Tổ (莫太祖) | ||

| Minh Đức Nguyên Bảo | 明德元寶 | 1527–1530 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Thái Tổ (莫太祖) | ||

| Đại Chính Thông Bảo | 大正通寶 | 1530–1540 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Thái Tông (莫太宗) |  | |

| Quang Thiệu Thông Bảo | 光紹通寶 | 1531–1532 | None | Quang Thiệu Emperor (光紹帝) | ||

| Nguyên Hòa Thông Bảo | 元和通寶 | 1533–1548 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Trang Tông (黎莊宗) |  | |

| Quảng Hòa Thông Bảo | 廣和通寶 | 1541–1546 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Hiến Tông (莫憲宗) | _-_Scott_Semans.jpg) | |

| Vĩnh Định Thông Bảo | 永定通寶 | 1547 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Tuyên Tông (莫宣宗) | ||

| Vĩnh Định Chí Bảo | 永定之寶 | 1547 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Tuyên Tông (莫宣宗) | ||

| Quang Bảo Thông Bảo | 光寶通寶 | 1554–1561 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Tuyên Tông (莫宣宗) | None | |

| Thái Bình Thông Bảo (中) | 太平通寶 | 1558–1613 | Nguyễn lords (阮主) | Nguyễn Hoàng (阮潢) | None | _-_Nguy%E1%BB%85n_lords_issue_-_Scott_Semans_03.jpg) |

| Thái Bình Phong Bảo | 太平豐寶 | 1558–1613 | Nguyễn lords (阮主) | Nguyễn Hoàng (阮潢) | None | |

| Bình An Thông Bảo | 平安通寶 | 1572–1623 | Trịnh lords (鄭主) | Trịnh Tùng (鄭松) | None | |

| Gia Thái Thông Bảo (中)[49] | 嘉泰通寶 | 1573–1599 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Thế Tông (黎世宗) | None | |

| Càn Thống Nguyên Bảo | 乾統元寶 | 1593–1625 | Mạc (莫)[lower-alpha 20] | Mạc Kính Cung (莫敬恭) | None | |

| An Pháp Nguyên Bảo | 安法元寶 | 1593–1625 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Kính Cung (莫敬恭) | None | .png) |

| Thái Bình Thông Bảo (中) | 太平通寶 | 1593–1625 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Kính Cung (莫敬恭) | None | |

| Thái Bình Thánh Bảo | 太平聖寶 | 1593–1625 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Kính Cung (莫敬恭) | None | |

| Thái Bình Pháp Bảo | 太平法寶 | 1593–1625 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Kính Cung (莫敬恭)[50][51] | None | |

| Khai Kiến Thông Bảo | 開建通寶 | 1593–1625 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Kính Cung (莫敬恭) | ||

| Sùng Minh Thông Bảo | 崇明通寶 | 1593–1625 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Kính Cung (莫敬恭) | ||

| Chính Nguyên Thông Bảo | 正元通寶 | 1593–1625 | Mạc (莫) | Mạc Kính Cung (莫敬恭) | None |  |

| Vĩnh Thọ Thông Bảo | 永壽通寶 | 1658–1661 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Thần Tông (黎神宗) | ||

| Tường Phù Nguyên Bảo[lower-alpha 21] (中) | 祥符元寶 | 1659–1685 | Đức Xuyên (徳川) | Đức Xuyên Gia Cương (徳川 家綱) | None | |

| Trị Bình Thông Bảo (中) | 治平通寶 | 1659–1685 | Đức Xuyên (徳川) | Đức Xuyên Gia Cương (徳川 家綱) | None | None |

| Trị Bình Nguyên Bảo (中)[54] | 治平元寶 | 1659–1685 | Đức Xuyên (徳川) | Đức Xuyên Gia Cương (徳川 家綱) | None | |

| Nguyên Phong Thông Bảo (中) | 元豊通寳 | 1659–1685 | Đức Xuyên (徳川) | Đức Xuyên Gia Cương (徳川 家綱) | None | |

| Hi Ninh Nguyên Bảo (中) | 熈寧元寳 | 1659–1685 | Đức Xuyên (徳川) | Đức Xuyên Gia Cương (徳川 家綱) | None | |

| Thiệu Thánh Nguyên Bảo (中) | 紹聖元寳 | 1659–1685 | Đức Xuyên (徳川) | Đức Xuyên Gia Cương (徳川 家綱) | None | |

| Gia Hựu Thông Bảo (中) | 嘉祐通寳 | 1659–1685 | Đức Xuyên (徳川) | Đức Xuyên Gia Cương (徳川 家綱) | None | |

| Vĩnh Trị Thông Bảo | 永治通寶 | 1678–1680 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hi Tông (黎熙宗) | ||

| Vĩnh Trị Nguyên Bảo | 永治元寶 | 1678–1680 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hi Tông (黎熙宗) | None | |

| Vĩnh Trị Chí Bảo | 永治至寶 | 1678–1680 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hi Tông (黎熙宗) | None | |

| Chính Hòa Thông Bảo | 正和通寶 | 1680–1705 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hi Tông (黎熙宗) |  | |

| Chính Hòa Nguyên Bảo | 正和元寶 | 1680–1705 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hi Tông (黎熙宗) | None | |

| Vĩnh Thịnh Thông Bảo | 永聖通寶 | 1706–1719 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Dụ Tông (黎裕宗) | ||

| Bảo Thái Thông Bảo | 保泰通寶 | 1720–1729 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Dụ Tông (黎裕宗) | ||

| Thiên Minh Thông Bảo | 天明通寶 | 1738–1765 | Nguyễn lords (阮主) | Nguyễn Phúc Khoát (阮福濶) | _-_Scott_Semans_02.jpg) | |

| Ninh Dân Thông Bảo[55][56][57][58] | 寧民通宝[lower-alpha 22] | 1739–1741 | None | Nguyễn Tuyển (阮選), Nguyễn Cừ (阮蘧), and Nguyễn Diên (阮筵)[lower-alpha 23] | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Thông Bảo | 景興通寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Thông Bảo[59] | 景興通宝 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Trung Bảo | 景興中寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Trung Bảo[60] | 景興中宝 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Chí Bảo[61] | 景興至寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) |  | |

| Cảnh Hưng Vĩnh Bảo | 景興永寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) |  | |

| Cảnh Hưng Đại Bảo | 景興大寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Thái Bảo | 景興太寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) |  | |

| Cảnh Hưng Cự Bảo[62] | 景興巨寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Cự Bảo | 景興巨宝 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Trọng Bảo | 景興重寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) |  | |

| Cảnh Hưng Tuyền Bảo | 景興泉寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) |  | |

| Cảnh Hưng Thuận Bảo | 景興順寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Nội Bảo | 景興內寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Nội Bảo | 景興內宝 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) |  | |

| Cảnh Hưng Dụng Bảo | 景興用寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Dụng Bảo[63] | 景興踊寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | None | |

| Cảnh Hưng Lai Bảo | 景興來寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | None | |

| Cảnh Hưng Thận Bảo | 景興慎寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | None | |

| Cảnh Hưng Thọ Trường | 景興壽長 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | None | |

| Cảnh Hưng Chính Bảo[64] | 景興正寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) |  | |

| Cảnh Hưng Anh Bảo | 景興英寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | None | |

| Cảnh Hưng Tống Bảo | 景興宋寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Thông Dụng | 景興通用 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | ||

| Cảnh Hưng Lợi Bảo[65] | 景興利寶 | 1740–1786 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Hiển Tông (黎顯宗) | None | |

| Thái Đức Thông Bảo | 泰德通寶 | 1778–1788 | Tây Sơn (西山) | Thái Đức (泰德) | ||

| Nam Vương Thông Bảo | 南王通寶 | 1782–1786 | Trịnh lords (鄭主) | Trịnh Khải (鄭楷) | None | |

| Nam Vương Cự Bảo | 南王巨寶 | 1782–1786 | Trịnh lords (鄭主) | Trịnh Khải (鄭楷) | None | |

| Minh Đức Thông Bảo | 明德通寶 | 1787 | Tây Sơn (西山) | Thái Đức (泰德) | None | |

| Chiêu Thống Thông Bảo | 昭統通寶 | 1787–1789 | Revival Lê (黎中興) | Lê Mẫn Đế (黎愍帝) | ||

| Quang Trung Thông Bảo | 光中通寶 | 1788–1792 | Tây Sơn (西山) | Quang Trung (光中) | ||

| Quang Trung Thông Bảo | 光中通宝 | 1788–1792 | Tây Sơn (西山) | Quang Trung (光中) | ||

| Quang Trung Đại Bảo | 光中大宝 | 1788–1792 | Tây Sơn (西山) | Quang Trung (光中) | ||

| Càn Long Thông Bảo An Nam[lower-alpha 24] (中)[66] | 乾隆通寶 安南 | 1788–1789 | Thanh (清) | Càn Long Emperor (乾隆帝) | ||

| Cảnh Thịnh Thông Bảo | 景盛通寶 | 1793–1801 | Tây Sơn (西山) | Cảnh Thịnh (景盛) | ||

| Cảnh Thịnh Đại Bảo | 景盛大寶 | 1793–1801 | Tây Sơn (西山) | Cảnh Thịnh (景盛) | None | |

| Bảo Hưng Thông Bảo | 寶興通寶 | 1801–1802 | Tây Sơn (西山) | Cảnh Thịnh (景盛) | _-_Scott_Semans_03.jpg) | |

| Gia Hưng Thông Bảo | 嘉興通寶 | 1802–1820 | Nguyễn (阮) | Gia Long (嘉隆) | None | |

| Gia Long Thông Bảo | 嘉隆通寶 | 1802–1820 | Nguyễn (阮) | Gia Long (嘉隆) | ||

| Gia Long Cự Bảo | 嘉隆巨寶 | 1802–1820 | Nguyễn (阮) | Gia Long (嘉隆) | None | |

| Minh Mạng Thông Bảo | 明命通寶 | 1820–1841 | Nguyễn (阮) | Minh Mạng (明命) | ||

| Trị Nguyên Thông Bảo | 治元通寶 | 1831–1834 | None | Lê Văn Khôi (黎文𠐤) | ||

| Trị Bình Thông Bảo (中) | 治平通寶 | 1831–1834 | None | Lê Văn Khôi (黎文𠐤) | ||

| Nguyên Long Thông Bảo | 元隆通寶 | 1833–1835 | None | Nông Văn Vân (農文雲) | ||

| Thiệu Trị Thông Bảo | 紹治通寶 | 1841–1847 | Nguyễn (阮) | Thiệu Trị (紹治) | ||

| Tự Đức Thông Bảo | 嗣德通寶 | 1847–1883 | Nguyễn (阮) | Tự Đức (嗣德) | ||

| Tự Đức Bảo Sao | 嗣德寶鈔 | 1861–1883 | Nguyễn (阮) | Tự Đức (嗣德) | ||

| Kiến Phúc Thông Bảo | 建福通寶 | 1883–1884 | Nguyễn (阮) | Kiến Phúc (建福) | None | |

| Hàm Nghi Thông Bảo | 咸宜通寶 | 1884–1885 | Nguyễn (阮) | Hàm Nghi (咸宜) | None | |

| Đồng Khánh Thông Bảo | 同慶通寶 | 1885–1888 | Nguyễn (阮) | Đồng Khánh (同慶) | None | |

| Thành Thái Thông Bảo | 成泰通寶 | 1888–1907 | Nguyễn (阮) | Thành Thái (成泰) | None | |

| Duy Tân Thông Bảo | 維新通寶 | 1907–1916 | Nguyễn (阮) | Duy Tân (維新) | None | |

| Khải Định Thông Bảo | 啓定通寶 | 1916–1925 | Nguyễn (阮) | Khải Định (啓定) | None | |

| Bảo Đại Thông Bảo | 保大通寶 | 1926–1945[lower-alpha 25] | Nguyễn (阮) | Bảo Đại (保大) | None |

Unidentified Vietnamese coins from 1600 and later

At various times many rebel leaders proclaimed themselves as Lords (主), Kings (王), and Emperors (帝), and had produced their own coinage with their reign names and titles on them, but as their rebellions would prove unsuccessful or brief their reigns and titles would go unrecorded in Vietnamese history, therefore coins produced by their rebellions cannot easily be classified. Coins were also often privately cast and these coins were sometimes of high quality or well-made imitations of imperial coinage, though often they would bear the same inscriptions as already circulating coinage, sometimes they would have "newly invented" inscriptions.[68] The Nguyễn lords that ruled over Southern Vietnam had also produced their own coinage at various times as they were the de facto kings of the South, but as their rule wasn't official, it is currently unknown what coins can be attributed to which Nguyễn lord. Though since Edouard Toda has made his list in 1882 several of the coins that he had described as "originating from the Quảng Nam province" have been ascribed to the Nguyễn lords that the numismatists of his time couldn't identify. During the rule of the Nguyễn lords many foundries for private mintage were also opened and many of these coins bear the same inscriptions as government cast coinage or even bear newly invented inscriptions making it hard to attribute these coins.[69]

The following list contains Vietnamese cash coins whose origins cannot be (currently) established:

| Inscription (chữ Quốc ngữ) | Inscription (Hán tự) | Notes | Toda image | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiệu Thánh Nguyên Bảo | 紹聖元寶 | |||

| Minh Định Tống Bảo | 明定宋寶 | "Tống Bảo" (宋寶) is written in Seal script. |  | |

| Cảnh Nguyên Thông Bảo | 景元通寶 | Appears in both Regular script, and Seal script. | ||

| Thánh Tống Nguyên Bảo | 聖宋元寶 |  | ||

| Càn Nguyên Thông Bảo | 乾元通寶 | Produced in the upper parts of Northern Vietnam. | ||

| Phúc Bình Nguyên Bảo | 福平元寶 | Written in Seal script. | ||

| Thiệt Quý Thông Bảo | 邵癸通寶 | Written in both Running hand and Seal script. | ||

| Dương Nguyên Thông Bảo | 洋元通寶 | Appear in multiple sizes. |  | |

| Thiệu Phù Nguyên Bảo | 紹符元寶 | Written in Seal script. | ||

| Nguyên Phù Thông Bảo | 元符通寶 | Written in Seal script. |  | |

| Đại Cung Thánh Bảo | 大工聖寶 | |||

| Đại Hòa Thông Bảo | 大和通寶 | The reverse is rimless. |  | |

| Cảnh Thì Thông Bảo | 景底通寶 | The "底" closely resembles a "辰" | ||

| Thiên Nguyên Thông Bảo | 天元通寶 | A variant exists where the "元" is written in Seal script. | ||

| Nguyên Trị Thông Bảo | 元治通寶 | The characters "治" and "寶" are written in Seal script. | ||

| Hoàng Hi Tống Bảo | 皇熙宋寶 | |||

| Khai Thánh Nguyên Bảo | 開聖元寶 | |||

| Thiệu Thánh Thông Bảo | 紹聖通寶 | |||

| Thiệu Thánh Bình Bảo | 紹聖平寶 | the reverse is rimless. | ||

| Thiệu Tống Nguyên Bảo | 紹宋元寶 | |||

| Tường Tống Thông Bảo | 祥宋通寶 | |||

| Tường Thánh Thông Bảo | 祥聖通寶 | |||

| Hi Tống Nguyên Bảo | 熙宋元寶 | |||

| Ứng Cảm Nguyên Bảo | 應感元寶 | |||

| Thống Phù Nguyên Bảo | 統符元寶 | |||

| Hi Thiệu Nguyên Bảo | 熙紹元寶 | |||

| Chính Nguyên Thông Bảo | 正元通寶 | Variants exist with rimmed and rimless reverses, as well as one where there's a dot or a crescent on the reverse. | ||

| Thiên Đức Nguyên Bảo | 天德元寶 | |||

| Hoàng Ân Thông Bảo | 皇恩通寶 | |||

| Thái Thánh Thông Bảo | 太聖通寶 | |||

| Đại Thánh Thông Bảo | 大聖通寶 | |||

| Chánh Hòa Thông Bảo | 政和通寶 | A variant exists where there's a crescent a dot on the reverse, and another one with only the crescent. | ||

| Thánh Cung Tứ Bảo[lower-alpha 26] | 聖宮慈寶 | None | ||

| Thánh Trần Thông Bảo | 聖陳通寶 | None | ||

| Đại Định Thông Bảo | 大定通寶 | None |  | |

| Chính Long Nguyên Bảo | 正隆元寶 | None | ||

| Hi Nguyên Thông Bảo | 熙元通寶 | None | ||

| Cảnh Nguyên Thông Bảo | 景元通寶 | None |  | |

| Tống Nguyên Thông Bảo | 宋元通寶 | None |  | |

| Thiên Thánh Nguyên Bảo | 天聖元寶 | None | ||

| Thánh Nguyên Thông Bảo | 聖元通寶 | None |  | |

| Chính Pháp Thông Bảo | 正法通寶 | None | ||

| Tây Dương Phù Bảo | 西洋符寶 | None | ||

| Tây Dương Bình Bảo | 西洋平寶 | None | ||

| An Pháp Nguyên Bảo | 安法元寶 | Most often attributed to Lê Lợi (黎利).[70][71] | ||

| Bình Nam Thông Bảo | 平南通寶 | Often attributed to the Nguyễn lords (阮主). | None |

Machine-struck cash coins made by the French government

During the time that Vietnam was under French administration, the French started minting cash coins for circulation first for within the colony of Cochinchina and then for the other regions of Vietnam. These coins were minted in Paris and were all struck as opposed to the contemporary cast coinage that already circulated within Vietnam.[72][73][74][75]

After the French had annexed Cochinchina from the Vietnamese, cash coins would remain to circulate in the region and depending on their weight and metal (as Vietnamese cash coins made from copper, tin, and zinc circulated simultaneously at the time at fluctuating rates) were accepted at 600 to 1000 cash coins for a single Mexican or Spanish 8 real coin or 1 piastre.[39][76] In 1870 the North German company Dietrich Uhlhorn started privately minting machine-struck Tự Đức Thông Bảo (嗣德通寶) coins as the demand for cash coins in French Cochinchina was high.[39][76] The coin weighed 4 grams which was close to the official weight of 10 phần (3.7783 grams) which was the standard used by the imperial government at the time. Around 1875 the French introduced holed 1 cent coins styled after the Vietnamese cash.[39][76] In 1879 the French introduced the Cochinchinese Sapèque with a nominal value of 1⁄500 piastre, but the Vietnamese population at the time still preferred the old Tự Đức Thông Bảo coins despite their lower nominal value.[39][40] The weight and size of the French Indochinese 1 cent coin was reduced and the coin was holed in 1896 in order to appear more similar to cash coins, this was done to reflect the practice of stringing coins together and be carried on a belt or pole because Oriental garments at the time did not have pockets.[39] The French production of machine-struck cash coins was halted in 1902.[39][77] As there were people in Hanoi and Saigon that did not want to give up on the production of machine-struck cash coins, a committee decided to strike zinc Sapèque coins with a nominal value of 1⁄600 piastre, these coins were produced at the Paris Mint and were dated 1905 despite being put into circulation only in 1906.[39] These coins corroded and broke quite easily which made them unpopular and their production quickly ceased.[39]

- The 1907 Annual Report by missionary Mgr. Gendreau of the Groupe des Mission du Tonkin.

After Khải Định became Emperor in 1916, Hanoi reduced the funds to cast Vietnamese cash coins which had a dissatisfying effect on the Vietnamese market as the demand for cash coins remained high, so another committee was formed in Hanoi that ordered the creation of machine-struck copper-alloy Khải Định Thông Bảo (啓定通寶) cash coins to be minted in Haiphong, these coins weighed more than the old French Sapèques and were around 2.50 grams and were accepted at 1⁄500 piastre.[39] There were 27 million Khải Định Thông Bảo of the first variant produced, while the second variant of the machine-struck Khải Định Thông Bảo had a mintage of 200 million, which was likely continued after the ascension of Emperor Bảo Đại in 1926 which was normal as previous Vietnamese emperors also kept producing cash coins with the inscription of their predecessors for a period of time.[39] Emperor Bảo Đại had ordered the creation of cast Bảo Đại Thông Bảo (保大通寶) cash coins again which weighed 3.2 gram in 1933, while the French simultaneously began minting machine-struck coins with the same inscription that weighed 1.36 grams and were probably valued at 1⁄1000 piastre. There were two variants of this cash coins where one had a large "大" (Đại) while the other had a smaller "大".[78][39]

| Denomination | Obverse inscription Hán tự (chữ Quốc ngữ) | Reverse inscription | Metal | Years of mintage | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Sapèque (1⁄500 piastre) | 當二 – 大法國之安南 (Đáng Nhị – Đại Pháp Quốc chi An Nam) | Cochinchine Française | copper | 1879–1885 | |

| 2 Sapèque (1⁄500 piastre) | 當二 – 大法國之安南 (Đáng Nhị – Đại Pháp Quốc chi An Nam) | Indo-Chine Française | copper | 1887–1902 | |

| 1 Sapèque (1⁄600 piastre) | 六百分之一 – 通寶 (Lục Bách Phân chi Nhất – Thông Bảo) | Protectorat du Tonkin | zinc | 1905 | |

| 1 Sapèque (1⁄500 piastre) | 啓定通寶 (Khải Định Thông Bảo)[79] | Copper-alloy | 1921–1925 | ||

| 1 Sapèque (1⁄1000 piastre) | 保大通寶 (Bảo Đại Thông Bảo) | Copper-alloy | 1933–1945 |

| Gallery and notes |

There were several efforts by French administration to produce machine-struck cash (sapèque):

|

Flying dragon. Phi long (coin) of Khải Định |

| Emperors Khải Định (1916–1925) and Bảo Đại (1925–1945)

produced both cast and machine-struck cash. |

Recovery of cash coins in modern Vietnam

.jpg)

In modern Vietnam the supply of undiscovered cash coins is rapidly declining as large amounts of Vietnamese cash coins were excavated during the 1980s and 1990s, in Vietnam the excavation of antiques such as cash coins is an industry in itself and the cash coins are mostly being dug up by farmers. After the Vietnam War ended in 1975 a large number of metal detectors numbering in the many thousands were left behind in the former area of South Vietnam which helped fuel the rise of this industry. The antique bronze industry is mostly concentrated in small rural villages where farmers rent metal detectors to search their own lands for bronze antiques to then either sell as scrap or to dealers, these buyers purchase lumps of cash coins by either kilogramme or ton to then hire skilled people to search through these lumps of cash coins for sellable specimens, these coins are then sold to other dealers in Vietnam, China, and Japan. During the zenith of the coin recovery business in Vietnam the number of bulk coins found on a monthly basis was fifteen tons but only roughly fifteen kilogrammes of those coins were sellable and the rest of the coins would melted down as scrap metal. As better metal detectors that could search deeper more Vietnamese cash coins were discovered but in modern times the supply of previously undiscovered Vietnamese cash coins is quickly diminishing.[80][81]

In modern times many Vietnamese cash coins are found in sunken shipwrecks which are mandated by Vietnamese law to be the property of the Vietnamese government as salvaged ships of which the owner was unknown belong to the state.[82][83]

Notable recent large finds of cash coins in Vietnam include 100 kilogrammes of Chinese cash coins and 35 kilogrammes of Vietnamese cash coins being unearthed in the province of Quảng Trị in 2007,[84][85] 52.9 kilogrammes of Chinese and Vietnamese cash coins being unearthed in a cemetery in Haiphong in 2008,[86] 50 kilogrammes of cash coins in the province of Hà Nam in 2015,[87] and some Nagasaki trade coins in the province of Hà Tĩnh in 2018.[88][89]

See also

- Vietnamese dynasties

- Cash

- Chinese cash

- Japanese mon

- Korean mun

- Ryukyuan mon

Notes

- The term văn (文) was first used in Vietnam in 1861 and the coins were referred to as đồng tiền (銅錢, copper coins) or simply as coins. Denominations of the Vietnamese cash coins were based on their weight and metal alloys and their value was determined by these aspects and their individual quality.[4][5] In English these types of coins are referred to as "cash coins".

- These coins may alternatively be referred to as sous in French, which is also the French nickname name for the French 1 centime coin making it an equivalent to the English term "Penny".[6]

- The colour turns purple if you have visited the page in the past.

- The reign title was "Thái Bình" (太平) but the actual inscription of the coinage reads "Đại Bình Hưng Bảo" (大平興寶).

- "Uncertain attribution".

- This cash coin is listed in Barker's Cash coins of Viet Nam but his example is a private issue of about 1580. No dynastic cash coin with this inscription is known to exist.

- This is a privately produced cash coin which was falsely attributed to the Lý dynasty by Eduardo Toda y Güell, many of them are actually from the 1500s -1800s

- This is a privately produced cash coin from the 1500s which has nothing to do with the Lý dynasty.

- This cash coin was privately produced and is considered to be falsely attributed to Nguyễn Hi Nguyên (阮熙元) by some scholars.

- These cash coins turned out to be a series of private coins similar to the official Hồ style. However no such reign title existed under the reign of the Hồ dynasty.

- These cash coins turned out to be privately produced issue from the early 1600s, they are reign title copies of Chinese cash coins but are listed in numismatic literature.

- This cash coin turned out to be a Ming trade cash coin which was cast around the year 1590 at Quanzhou, Fujian.

- during the Chinese (Minh dynasty) occupation these coins were issued as payments to Chinese soldiers, Giao Chỉ Thông Bảo coins are poorly made from lead and sand.

- Coins issued during the Lam Sơn uprising were cast as payment for the anti-Chinese rebels.

- This cash coin was attributed to Lê Lợi (黎利) by Eduardo Toda y Güell, but later turned out to be private issue from about 1600.

- This cash coin was attributed to Lê Lợi (黎利) by Eduardo Toda y Güell, but later turned out to be private issue produced between the years 1750 and 1850.

- This cash coin was attributed to Lê Lợi (黎利) by Eduardo Toda y Güell, but later turned out to be private issue produced after the year 1600.

- This cash coin turned out to be a rare private cash coin made during a brief Trần restoration in the early 1500s. Unlike what Toda claimed it is not made from tin and lead, but a hard white bronze composition.

- Despite bearing the reign title "Thái Hòa Thông Bảo" all coins actually bear the inscription "Đại Hòa Thông Bảo" (大和通寶).

- From this point onwards the monarchs of the Mạc dynasty were only in control of the Cao Bằng Province, which they had declared as an independent country for 75 years.

- The "Tường Phù Nguyên Bảo" (祥符元寶), "Trị Bình Thông Bảo" (治平通寶), and "Trị Bình Nguyên Bảo" (治平元寶) were Japanese trade coins minted in Nagasaki for trade with Vietnam and the Netherlands.[52] In Vietnam they were imported by the Nguyễn lords.[53]

- The character "宝" is an abbreviated version of "寶" commonly found in Semi-cursive script. Note from Eduardo Toda y Güell's Annam and its minor currency where the coin was described of being "of doubtful origin" but has been identified since.

- The leaders of the Ninh Xá rebellion Nguyễn Tuyển and Nguyễn Cừ were brothers while Nguyễn Diên was their nephew.

- Cast as payments for Chinese soldiers stationed in Vietnam during the Battle of Ngọc Hồi-Đống Đa.

- The production of these coins probably lasted into 1941 or 1942 because the occupying Japanese forces wanted the copper and were acquiring all of the cash coins they could find and stockpiling them in Haiphong for shipment to Japan for the production of war materials.[67]

- The coins from this part of the list and below are from Dr. R. Allan Barker (2004) while the coins above are from Edouard Toda (1882).

References

- Vietnamnet – Sử Việt, đọc vài quyển Chương IV "Tiền bạc, văn chương và lịch sử" (in Vietnamese)

- "Definition of guàn (貫)". Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- Hán-Việt từ điển của Thiều Chửu. Nhà Xuất Bản TP. Hồ chí Minh. 2002 (in Vietnamese)

- Dai Nam Hoi Dien Su Le" (Administrative statute of Dai Nam) published by Thuận Hóa, Viet Nam 1993. (in Vietnamese)

- "Dai Nam Thuc Luc" (A veritable chronicle of Đại Nam) published by Khoa Hoc Xa Hoi, Hanoi 1962, written by the Cabinet of Nguyễn dynasty. (in Vietnamese)

- Le bas-monnayage annamite au niên hiệu de Gia Long (1804-1827) by François Joyaux. Retrieved: 22 April 2018. (in French)

- Toda 1882, p. 6.

- Manuel de Rivas, Idea del Imperio de Anam. Published: 1858 Manila, Spanish East Indies (in Castilian)

- Toda 1882, p. 9.

- Tạ Chí Đại Trường (2004). "Tiền bạc, văn chương và lịch sử". Sử Việt, đọc vài quyển (in Vietnamese). Văn Mới Publishing House.

- Eduardo Toda y Güell (1882). "Annam and its Minor Currency - Chapter XI. - The 吳 Ngo Family. The twelve 使君 Suquan. The 丁 Dinh Dynasty. The former 黎 Le Dynasty. - 940-1010 A.D. - The 吳 Ngo Family - 940-948". Art-Hanoi. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Alotrip.com – We book, you travel. Ancient Vietnamese coins – Episode 1. Published: Thursday, 12 Mar 2015 . Last updated: Thursday, 25 Jun 2015 09:01 Retrieved: 29 June 2017.

- David, Hartill (September 22, 2005). Cast Chinese Coins. Trafford, United Kingdom: Trafford Publishing. p. 432. ISBN 978-1412054669.

- Eduardo Toda y Güell (1882). "Annam and its Minor Currency - Chapter XII. The 李 Ly Dynasty. - 1010-1225". Art-Hanoi. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Eduardo Toda y Güell (1882). "Annam and its Minor Currency - Chapter XIII. - The 陳 Tran Dynasty. - 1225-1414". Art-Hanoi. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Linh, Vietnamese in Vancouver Thông bảo hội sao. (in Vietnamese) Xin visa du lịch – Đặt phòng & vé máy bay – Hỗ trợ 24/7 Retrieved: 16 February 2018.

- "Over-600-year history of Vietnam banknotes". Vietnamnet. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Nhà xuất bản Khoa học xã hội, 1998, tập 2,trang 189 (in Vietnamese)

- Lịch triều hiến chương loại chí, tập 2, trang 112, Nhà xuất bản giáo dục, 2007 (in Vietnamese)

- "Vietnamese Money Through Time". Vietnam Culture (Brings Vietnamese culture to the world). 3 March 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- Asian Numismatic Museum (Sudoku One) Coins of the Hồ Dynasty 胡朝 1400 - 1407 AD. Thanh Nguyen and Thieu Nguyen. Retrieved: 19 July 2017.

- Mirua Gosen. Published: 1966. (in Japanese)

- Lục Đức Thuận, Võ Quốc Ky, sách đã dẫn (in Vietnamese)

- Việt Touch VIET NAM COINS & PAPER NOTES. AUTHOR: Thuan D. Luc COLLECTION: Bao Tung Nguyen Retrieved: 24 June 2017.

- Dutch-Asiatic trade 1620–1740 by Kristof Glamann, Danish Science Press published.

- Japanese coins in Southern Vietnam and the Dutch East India Company 1633–1638 by Dr. A van Aelst

- Travel is easier with Linh Nhà Hậu Lê (Lê Trung Hưng). (in Vietnamese) Xin visa du lịch – Đặt phòng & vé máy bay – Hỗ trợ 24/7 Retrieved: 22 June 2017.

- "Canh Hung coins". Luke Roberts at the Department of History – University of California at Santa Barbara. 24 October 2003. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Alotrip.com – We book, you travel. Ancient Vietnamese coins – Episode 2. Published: Thursday, 12 Mar 2015 . Last updated: Monday, 01 Jun 2015 14:22. Retrieved: 29 June 2017.

- Eduardo Toda y Güell (1882). "Annam and its Minor Currency - Chapter XIX. - The 西山 Tay-son Rebellion. 1764-1801". Art-Hanoi. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Art-Hanoi CURRENCY TYPES AND THEIR FACE VALUES DURING THE TỰ ĐỨC ERA. This is a translation of the article "Monnaies et circulation monetairé au Vietnam dans l'ère Tự Đức (1848–1883) by François Thierry Published in Revue Numismatique 1999 (volume # 154). Pgs 267-313. This translation is from pages 274-297. Translator: Craig Greenbaum. Retrieved: 24 July 2017.

- Eduardo Toda y Güell (1882). "Annam and its Minor Currency - Chapter XX. Chinese intervention in Tunquin, and the 阮 Nguyen Dynasty". Art-Hanoi. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- H.A. Ramsden, The high value issues of the Tự Đức series of Annamese coins, East Asia Journal, vol. 2, 55-62, 1995.

- Tang Guo Yen, Chang Shi Chuan Yuenan lishi huobi (in Vietnamese Lich suu dong tien Vietnam – The Vietnamese historical currency), 1993, published by the Yunnan and Guangxi Numismatic Society (in Mandarin Chinese).

- "Vietnamese Coin – Tự Đức Bao Sao 9 Mach". Vladimir Belyaev (Charm.ru – Chinese Coinage Website). 30 November 2001. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- François Thierry de Crussol, Catalogue des monnaies Vietnamiennes, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, 1987. (in French)

- timdolinghcmc@gmail.com (29 December 2015). "Saigon-Cholon in 1868, by Charles Lemire". First published in the 1869 journal Annales des voyages, de la géographie, de l’histoire et de l’archéologie, edited by Victor-Adolphe Malte-Brun, Charles Lemire’s article “Coup d’oeil sur la Cochinchine Française et le Cambodge” gives us a fascinating portrait of Saigon-Chợ Lớn less than 10 years after the arrival of the French. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Howard A. Daniel, III 2018, p. 29.

- "Sapeque and Sapeque-Like Coins in Cochinchina and Indochina (交趾支那和印度支那穿孔錢幣)". Howard A. Daniel III (The Journal of East Asian Numismatics – Second issue). 20 April 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- Howard A. Daniel, III 2018, p. 31.

- Howard A. Daniel, III 2018, p. 32.

- François Thierry de Crussol (蒂埃里) (14 September 2015). "Bas monnayage de Thành Thái 成泰 (1889-1907) - Brass coinage of Thành Thái era (1889-1907)" (in French). TransAsiart. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- "Vietnamese charms in Vietnam War era". Tony Luc (Charm.ru - Chinese Coinage Website). 29 April 1998. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "Charms with Quang Trung's Reign Title". Tony Luc and Vladimir Belyaev (Charm.ru - Chinese Coinage Website). 2 May 1998. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "Charms with Ham Nghi's Reign Title". Tony Luc and Vladimir Belyaev (Charm.ru - Chinese Coinage Website). 30 April 1998. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- "Khai Dinh Trong Bao charm". Tony Luc and Vladimir Belyaev (Charm.ru - Chinese Coinage Website). 29 April 1998. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- Asian Numismatic Museum (Sudoku One). Vietnamese Thien Tu and Kai Yuan Style. Thiên Tư Nguyên Bảo 天資元寶 Thư pháp, viết theo phong cách, Trung Quốc Ka Yuan. Retrieved: 19 July 2017.

- Scott Seman's World Coins – VIETNAM CASH 970 AD — 1945. Retrieved: 07 June 2018.

- Charms.ru Timeline and imperial coinage of Vietnam. Thuan D. Luc, and Vladimir A. Belyaev Published: 26 September 1998. Last updates: 29-April-2004. Retrieved: 24 June 2017.

- Nghệ Thuật Xưa Tiền tệ thời Nhà Mạc. (in Vietnamese) Published: 13 February 2016. Retrieved: 24 June 2017.

- Travel is easier with Linh Nhà Mạc (chữ Hán: 莫朝 – Mạc triều). Archived 2018-02-28 at the Wayback Machine (in Vietnamese) Xin visa du lịch – Đặt phòng & vé máy bay – Hỗ trợ 24/7 Retrieved: 24 June 2017.

- "Nagasaki export coins". Luke Roberts at the Department of History – University of California at Santa Barbara. 24 October 2003. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- Charms.ru Japan early trade coin and the commercial trade between Vietnam and Japan in the 17th century. Thuan Luc, May 1999. Retrieved: 24 June 2017.

- Chinese Coins (1268 coins from all Chinese dynasties.) – Korea, Japan, Vietnam by Lars Bo Christensen (Ancient Chinese Coins). Retrieved: 09 July 2018.

- Zeno.ru (The Zeno Oriental Coinage Database) Ninh Xá 寧舍 Rebellion 1739-1741 (Home » SOUTHEAST ASIA » Cash coins » Vietnam cash » Official and semi-official coins » Ninh Xá 寧舍 Rebellion 1739–1741). Retrieved: 22 April 2018.

- Miura Gosen (Miura Gosen 三浦吾泉, Annan senpu 安南錢譜, 3 vol. Tokyo 1965–1971, Terui, p. 93-3). (in Japanese)

- Nguyễn Phan Quang, « Khởi nghĩa Nguyễn Tuyển, Nguyễn Cừ », Nghiên Cứu Lịch Sử 1984-6 (219), pp. 56-67/82. (in Vietnamese)

- François Thierry, « Les monnaies Ninh Dân thông bảo », Bulletin de la Société Française de Numismatique, No 10, décembre 2010, pp. 285-288. Coin of the French National Library Collection (see François Thierry, Catalogue des monnaies vietnamiennes, Bibliothèque nationale, Paris 1988, n° 1136). (in French)

- Numista Canh Hung Thong Bao Country Vietnam – Empire (Lê dynasty – Vietnam). Quote: "The 25th King – LE HIEN TONG 1740–1786 ascended the throne, and during his reign a larger quantity of cash were cast than during that of any former king. This is one of them." Retrieved: 09 June 2018.

- Numista Canh Hung Trung Bao Country Vietnam – Empire (Lê dynasty – Vietnam). Quote: "The 25th King – LE HIEN TONG 1740–1786 ascended the throne, and during his reign a larger quantity of cash were cast than during that of any former king. This is one of them." Retrieved: 09 June 2018.

- Numista Canh Hung Tri Bao Country Vietnam – Empire (Lê dynasty – Vietnam). Quote: "The 25th King – LE HIEN TONG 1740–1786 ascended the throne, and during his reign a larger quantity of cash were cast than during that of any former king. This is one of them." Retrieved: 09 June 2018.

- Numista 1 Văn - Cảnh Hưng Cự Bảo Country Vietnam – Empire (Lê dynasty – Vietnam). Quote: "The 25th King – LE HIEN TONG 1740–1786 ascended the throne, and during his reign a larger quantity of cash were cast than during that of any former king. This is one of them." Retrieved: 09 June 2018.

- Charm.ru Vietnamese Coin Canh Hung Dung Bao by Vladimir Belyaev. Published: October 04, 1998. Retrieved: 29 March 2018.

- Numista Canh Hung Chinh Bao Country Vietnam – Empire (Lê dynasty – Vietnam). Quote: "The 25th King – LE HIEN TONG 1740–1786 ascended the throne, and during his reign a larger quantity of cash were cast than during that of any former king. This is one of them." Retrieved: 09 June 2018.

- N Ô M · S T U D I E S (A research project in the Vietnamese Nôm cultural heritage) Vietnamese Currency (Draft). Adapted from Niên biểu Việt Nam "Vietnamese Chronology" by Office of Preservation and Museology, Hanoi: Social Sciences Publishing House, 3rd edition. 1984. Pp. 133–50. Retrieved: 07 June 2018.

- François Thierry de Crussol (蒂埃里) (14 September 2015). "Monnaies de l'occupation chinoise (1788-1789) - Qian Long tongbao 乾隆通寶 coins of the Chinese occupation (1788-1789)" (in French). TransAsiart. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- French Southeast Asia Coins & Currency by Howard A. Daniel III (page 97).

- "Vietnam (Annam) Privately Minted Coins". Luke Roberts at the Department of History – University of California at Santa Barbara. 24 October 2003. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Charms.ru Coincidences of Vietnam and China cash coins legends. Francis Ng, People's Republic of China, Thuan D. Luc, United States, and Vladimir A. Belyaev, Russia March–June, 1999 Retrieved: 17 June 2017.

- Charms.ru WHO CAST THE AN PHAP NGUYEN BAO COIN? [1 .] Luc Duc Thuan Retrieved: 24 June 2017.

- Lacroix Désiré. Numismatique Annamite – Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient, Saigon 1900

- Vietnam Banknotes ▼ French Cochinchina coins. Việt Nam Lan Rừng – Published: March 18, 2013. Retrieved: 29 June 2017.

- Phạm Thăng. Tiền tệ Việt Nam theo dòng lịch sử. Toronto, Ontario: ?, 1995. (in Vietnamese)

- Bianconi, F. Cartes commerciales phyiques, adminsitratives et routières Tonkin. Paris: Imprimerie Chaix, 1886. (in French)

- Jean Lecompte (2000) Monnaies et Jetons des Colonies Françaises. ISBN 2-906602-16-7 (in French)

- Howard A. Daniel, III 2018, p. 28.

- Howard A. Daniel, III 2018, p. 30.

- Howard A. Daniel III (The Journal of East Asian Numismatics – Second edition). Page = 76.

- Linh, Vietnamese in Vancouver Khải Định Thông Bảo. (in Vietnamese) Xin visa du lịch – Đặt phòng & vé máy bay – Hỗ trợ 24/7 Retrieved: 10 February 2018.

- Sudokuone (Vietnam's Imperial History as Seen Through its Currency) The Supply of Vietnamese Coins by Dr. R. Allan Barker. Retrieved: 03 April 2018.

- Barker 2004, p. 10.

- "Vietnam salvager says ancient coins looted from shipwreck". Thanh Nien News. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Shipwreck off Vietnam yields 700-year-old coins and ceramics". United Press International, Inc. (UPI). 2 July 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "100kg of ancient Chinese coins unearthed in Vietnam". Noel Tan for the Southeast Asian Archeology Newsblog (through Thanh Nien News). 7 September 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "34kg of ancient coins unearthed in Vietnam". Noel Tan for the Southeast Asian Archeology Newsblog (through Vietnam Net Bridge). 9 November 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Vietnam Unearths Ancient Vietnamese, Chinese Coins". U.S. Rare Coin Investments. 13 August 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "50kg of old coins unearthed in Ha Nam - VietNamNet Bridge – Luong Manh Hai, 39, of Tri Lanh village in Ha Nam province discovered 50 kg while digging a foundation for a water tank". Thu Ly for VietnamNet. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Ancient Japanese coins found in central province". VietnamPlus (Sports – Society section). 14 March 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Ancient Japanese coins found in Hà Tĩnh". Viet Nam News (Life & Style section). 14 March 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

Sources

- ED. TODA. (1882) ANNAM and its minor currency. Hosted on Art-Hanoi. (Wikimedia Commons)

- Dr. R. Allan Barker. (2004) The historical Cash Coins of Viet Nam. ISBN 981-05-2300-9

- Howard A. Daniel, III - The Catalog and Guidebook of Southeast Asian Coins and Currency, Volume I, France (3rd Edition). Published: 10 April 2018. ISBN 1879951045.

- Pham Quoc Quan, Nguyen Dinh Chien, Nguyen Quoc Binh and Xiong Bao Kang: Tien Kim Loai Viet Nam. Vietnamese Coins. Bao Tang Lich Su Viet Nam. National Museum of Vietnamese History. Ha noi, 2005. (in Vietnamese)

- Hội khoa học lịch sử Thừa Thiên Huế, sách đã dẫn. (in Vietnamese)

- Trương Hữu Quýnh, Đinh Xuân Lâm, Lê Mậu Hãn, sách đã dẫn. (in Vietnamese)

- Lục Đức Thuận, Võ Quốc Ky (2009), Tiền cổ Việt Nam, Nhà xuất bản Giáo dục. (in Vietnamese)

- Đỗ Văn Ninh (1992), Tiền cổ Việt Nam, Nhà xuất bản Khoa học xã hội. (in Vietnamese)

- Trương Hữu Quýnh, Đinh Xuân Lâm, Lê Mậu Hãn chủ biên (2008), Đại cương lịch sử Việt Nam, Nhà xuất bản Giáo dục. (in Vietnamese)

- Viện Sử học (2007), Lịch sử Việt Nam, tập 4, Nhà xuất bản Khoa học xã hội. (in Vietnamese)

- Trần Trọng Kim (2010), Việt Nam sử lược, Nhà xuất bản Thời đại. (in Vietnamese)

- Catalogue des monnaies vietnamiennes (in French), François Thierry

- Yves Coativy, "Les monnaies vietnamiennes d'or et d'argent anépigraphes et à légendes (1820–1883)", Bulletin de la Société Française de Numismatique, février 2016, p. 57-62, (in French)

- Tien Kim Loai Viet Nam (Vietnamese Coins), Pham Quoc Quan, Hanoi, 2005. (in Vietnamese)

- W. Op den Velde, "Cash coin index. The Cash Coins of Vietnam", Amsterdam, 1996.

External links

- Collection Banknotes of Vietnam and the World

- Coins and Banknotes of Vietnam and French Indochina

- Cash coins of Vietnam 968 - 1945. Online Identifier

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coins of Vietnam. |

| Preceded by: Chinese cash Reason: independence |

Currency of Vietnam 970 – 1948 |

Succeeded by: French Indochinese piastre, North Vietnamese đồng Reason: abolition of the monarchy |

_-_Art-Hanoi_01.jpg)

.jpg)

_Art-Hanoi_02.jpg)

_02.jpg)