Vietnamese poetry

Vietnamese poetry originated in the form of folk poetry and proverbs. Vietnamese poetic structures include six-eight, double-seven six-eight, and various styles shared with Classical Chinese poetry forms, such as are found in Tang poetry; examples include verse forms with "seven syllables each line for eight lines," "seven syllables each line for four lines" (a type of quatrain), and "five syllables each line for eight lines." More recently there have been new poetry and free poetry.

With the exception of free poetry, a form with no distinct structure, other forms all have a certain structure. The tightest and most rigid structure was that of the Tang Dynasty poetry, in which structures of content, number of syllables per line, lines per poem, rhythm rule determined the form of the poem. This stringent structure restricted Tang poetry to the middle and upper classes and academia.

History

Beginnings

The first indication of Vietnamese literary activity dates back around 500 BCE during the Đông Sơn Bronze-age civilization. Poetic scenes of sun worship and musical festivity appeared on the famous eponymous drums of the period. Since music and poetry are often inextricable in the Vietnamese tradition, one could safely assume the Dong Son drums to be the earliest extant mark of poetry.[1]

In 987 CE, Do Phap Than co-authored with Li Chueh, a Chinese ambassador in Vietnam by matching the latter's spontaneous oration in a four-verse poem called "Two Wild Geese".[2] Poetry of the period proudly exhibited its Chinese legacy and achieved many benchmarks of classical Chinese literature. For this, China bestowed the title of Van Hien Chi Bang ("the Cultured State") on Vietnam.[3]

All the earliest literature from Vietnam is necessarily written in Chinese (though read in the Sino-Vietnamese dialect.[4]) No writing system for vernacular Vietnamese existed until the thirteenth century, when chữ nôm ("Southern writing", often referred to simply as Nôm) — Vietnamese written using Chinese script — was formalized.[5] While Chinese remained the official language for centuries, poets could now choose to write in the language of their choice.

Folk poetry presumably flourished alongside classical poetry, and reflected the common man's life with its levity, humor and irony. Since popular poetry was mostly anonymously composed, it was more difficult to date and trace the thematic development of the genre.[6]

High-culture poetry in each period mirrored various sensibilities of the age. The poems of Lý dynasty (1010-1125) distinctively and predominantly feature Buddhist themes.[7] Poetry then became progressively less religiously oriented in the following dynasty, the Trần dynasty (1125-1400), as Confucian scholars replaced Buddhist priest as the Emperors' political advisers.[8] Three successive victorious defense against the Kublai Khan's Mongolian armies further emboldened Vietnamese literary endeavors, infusing poetry with celebratory patriotism.

Later Lê dynasty (1427-1788)

Literature in chữ nôm flourished in the fifteenth century during the Later Lê dynasty. Under the reign of Emperor Lê Thánh Tông (1460-1497), chữ nôm enjoyed official endorsement and became the primary language of poetry.[9] By this century, the creation of chu Nom symbolized the happy marriage between Chinese and vernacular elements and contributed to the blurring of the literary distinction between "high" and "low" cultures.[10]

Due to the civil strife between Trinh and Nguyen overlordship and other reasons, poetic innovation continued, though at a slower pace from the late fifteenth century to the eighteenth century. The earliest chữ nôm in phu, or rhymed verse,[11] appeared in the sixteenth century. Also in the same period, the famous "seven-seven-six-eight" verse form was also invented. Verse novels (truyen) also became a major genre. It was around the fifteenth century that people started linking the traditional "six-eight" iambic couplet verses of folk poetry together, playing on the internal rhyming between the sixth syllable of the eight line and the last syllable of the six line, so that end rhyme mutates every two lines.[12] Orally narrated verse novels using this verse pattern received immense popular support in a largely illiterate society.

In 1651 Father Alexandre de Rhodes, a Portuguese missionary, created a system to romanize Vietnamese phonetically, formalized as quốc ngữ ("the National Language") which, however, did not gain wide currency until the twentieth century.

Tây Sơn and Independent Nguyễn dynasty (1788-1862)

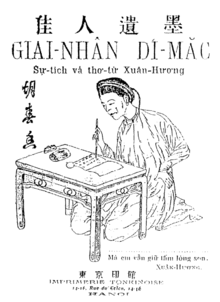

Itinerant performers recite these truyen, the most famous of which is the Tale of Kieu by Nguyễn Du, often said to be the national poem of Vietnam.[13] A contemporary of Nguyễn Du was Hồ Xuân Hương, a female author of masterful and boldly venereal verses.[14]

French colonial period (1862-1945)

Starting from the 1930s, quốc ngữ poems abounded, often referred to as thơ mới ("New Poetry"), which borrowed from Western traditions in both its free verse form as well as modern existential themes.[15]

Contemporary (1945-present)

The Second World War curbed some of this literary flourishing, though Vietnamese poetry would undergo a new period of development during the French resistance and the Vietnam War.[16]

Prosody

As in most metrical systems, Vietnamese meter is structured both by the count and the character of syllables. Whereas in English verse syllables are categorized by relative stress, and in classical Greek and Latin verse they are categorized by length, in Vietnamese verse (as in Chinese) syllables are categorized by tone. For metrical purposes, the 6 distinct phonemic tones that occur in Vietnamese are all considered as either "flat" or "sharp". Thus a line of metrical verse consists of a specific number of syllables, some of which must be flat, some of which must be sharp, and some of which may be either.

Like verse in Chinese and most European languages, traditional Vietnamese verse is rhymed. The combination of meter and rhyme scheme defines the verse form in which a poem is written.

Traditionally in Vietnamese 1 word = 1 character = 1 syllable. Thus discussions of poetry may refer, for example, to a seven-word line of verse, or to the tone of a word. In this discussion, syllable is taken to be the least-ambiguous term for the foundational prosodic unit.

Vowels and tones

Vowels can be simple (à, ca, cha, đá, lá, ta) or compound (biên, chiêm, chuyên, xuyên), and one of six tones is applied to every vowel.

Tone Class Tone Diacritic Listen Flat

(bằng)level a (no diacritic)

hanging à

Sharp

(trắc)tumbling ã

asking ả

sharp á

heavy ạ

In order to correspond more closely with Chinese rules of versification, older analyses sometimes consider Vietnamese to have eight tones rather than six. However, the additional two tones are not phonemic in Vietnamese and in any case roll up to the same Sharp tone class as they do in a six-tone analysis.

Rhyme

Use of rhyme in Vietnamese poetry is largely analogous to its use in English and other European languages; two important differences are the salience of tone class in the acceptability of rhymed syllables, and the prominence of structural back rhyme (rhyming a syllable at the end of one line with a syllable in the middle of the next). Rhyme connects lines in a poem together, almost always occurring on the final syllable of a line, and sometimes including syllables within the line.

In principle, Vietnamese rhymes exhibit the same features as English rhymes: Given that every syllable consists of CVC — an optional initial consonant or consonant cluster + a vowel (simple or compound) + an optional final consonant or consonant cluster — a "true" rhyme comprises syllables with different initial C and identical VC. However additional features are salient in Vietnamese verse.

Rhyming syllables do not require identical tones, but must be of the same tone class: either all Flat (e.g. dâu, màu, sầu), or all Sharp (e.g. đấy, cấy). Flat rhymes tend to create a feeling of gentleness and smoothness, whereas Sharp rhymes create a feeling of roughness, motion, wakefulness.

Rhyme can be further classified as "rich" or "poor". Rich rhyme (not to be confused with Rime riche) has the same tone class, and the same vowel sound: Flat (Phương, sương, cường, trường) or Sharp (Thánh, cảnh, lãnh, ánh).

Lầu Tần chiều nhạt vẻ thu

Gối loan tuyết đóng, chăn cù giá đông[17]

Poor rhyme has the same tone class, but slightly different vowel sounds: Flat (Minh, khanh, huỳnh, hoành) or Sharp (Mến, lẽn, quyện, hển)

Người lên ngựa kẻ chia bào

Rừng phong thu đã nhuộm màu quan san[18]

Finally, poets may sometimes use a "slant rhyme":

Người về chiếc bóng năm canh

Kẻ đi muôn dặm một mình xa xôi[19]

Verse form

Regulated verse

The earliest extant poems by Vietnamese poets are in fact written in the Chinese language, in Chinese characters, and in Chinese verse forms[20] — specifically the regulated verse (lüshi) of the Tang dynasty. These strict forms were favored by the intelligentsia, and competence in composition was required for civil service examinations.[21] Regulated verse — later written in Vietnamese as well as Chinese — has continued to exert an influence on Vietnamese poetry throughout its history.

At the heart of this family of forms are four related verse types: two with five syllables per line, and two with seven syllables per line; eight lines constituting a complete poem in each. Not only are syllables and lines regulated, so are rhymes, Level and Deflected tones (corresponding closely to the Vietnamese Flat and Sharp), and a variety of "faults" which are to be avoided. While Chinese poets favored the 5-syllable forms, Vietnamese poets favored the 7-syllable forms,[22] so the first of these 7-syllable forms is represented here in its standard Tang form:[23]

L L / D D / D L LA D D / L L / D D LA D D / L L / L D D L L / D D / D L LA L L / D D / L L D D D / L L / D D LA D D / L L / L D D L L / D D / D L LA - L = Level syllable; D = Deflected syllable; LA = Level syllable with "A" rhyme; / = pause.

The other 7-syllable form is identical, but with (for the most part) opposite assignments of Level and Deflected syllables. 5-syllable forms are similarly-structured, but with 2+3 syllable lines, rather than 2+2+3. All forms might optionally omit the rhyme at the end of the first line, necessitating tone alterations in the final three syllables. An additional stricture was that the two central couplets should be antithetical.[24]

Tang poetics allowed additional variations: The central 2 couplets could form a complete four-line poem (jueju), or their structure could be repeated to form a poem of indefinite length (pailü).[25]

While Vietnamese poets have embraced regulated verse, they have at times loosened restrictions, even taking frankly experimental approaches such as composing in six-syllable lines.[26] Though less prestigious (in part because it was not an element of official examinations), they have also written in the similar but freer Chinese "old style" (gushi).[27]

Lục bát

In contrast to the learned, official, and foreign nature of regulated verse, Vietnam also has a rich tradition of native, demotic, and vernacular verse. While lines with an odd number of syllables were favored by Chinese aesthetics, lines with an even number of syllables were favored in Vietnamese folk verse. Lục bát ("six-eight") has been embraced as the verse form par excellence of Vietnam. The name denotes the number of syllables in each of the two lines of the couplet. Like regulated verse, lục bát relies on syllable count, tone class, and rhyme for its structure; however, it is much less minutely regulated, and incorporates an interlocking rhyme scheme which links chains of couplets:

• ♭ • ♯ • ♭A • ♭ • ♯ • ♭A • ♭B • ♭ • ♯ • ♭B • ♭ • ♯ • ♭B • ♭C • ♭ • ♯ • ♭C • ♭ • ♯ • ♭C • ♭D - • = any syllable; ♭ = Flat (bằng) syllable; ♯ = Sharp (trắc) syllable; ♭A = Flat syllable with "A" rhyme.

- ♭ and ♯ are used only as handy mnemonic symbols; no connection with music should be inferred.

The verse also tends toward an iambic rhythm (one unstressed syllable followed by one stressed syllable), so that the even syllables (those mandatorily Sharp or Flat) also tend to be stressed.[28] While Sharp tones provide variety within lines, Flat tones dominate, and only Flat tones are used in rhymes. Coupled with a predominantly steady iambic rhythm, the form may suggest a steady flow, which has recommended itself to narrative.[29] Poets occasionally vary the form; for example, the typically Flat 2nd syllable of a "six" line may be replaced with a Sharp for variety.

Luc bat poems may be of any length: they may consist of just one couplet — as for example a proverb, riddle, or epigram — or they may consist of any number of linked couplets ranging from a brief lyric to an epic poem.[30]

A formal paraphrase of the first six lines of The Tale of Kiều suggests the effect of syllable count, iambic tendency, and interlocking rhyme (English has no analogue for tone):

Trăm năm trong cõi người ta, |

A century of life |

Song thất lục bát

Vietnam's second great native verse form intricately counterpoises several opposing poetic tendencies. Song thất lục bát ("double-seven six-eight") refers to an initial doublet — two lines of seven syllables each — linked by rhyme to a following lục bát couplet:

• • ♯ • ♭ • ♯A • • ♭ • ♯A • ♭B • ♭ • ♯ • ♭B • ♭ • ♯ • ♭B • ♭C • • ♯ • ♭C • ♯D • • ♭ • ♯D • ♭E • ♭ • ♯ • ♭E • ♭ • ♯ • ♭E • ♭F - • = any syllable; ♭ = Flat (bằng) syllable; ♯ = Sharp (trắc) syllable; ♯A = Sharp syllable with "A" rhyme.

In contrast to the lục bát couplet, the song thất doublet exactly balances the number of required Flat and Sharp syllables, but emphasises the Sharp with two rhymes. It bucks the tendency of even-syllabled lines in Vietnamese folk verse, calling to mind the scholarly poetic tradition of China. It necessitates the incorporation of anapestic rhythms (unstressed-unstressed-stressed) which are present but comparatively rare in the lục bát alone. Overall, the quatrain suggests tension, followed by resolution. It has been used in many genres, "[b]ut its great strength is the rendering of feelings and emotions in all their complexity, in long lyrics. Its glory rests chiefly on three works ... 'A song of sorrow inside the royal harem' ... by Nguyễn Gia Thiều, 'Calling all souls' ... by Nguyễn Du, and 'The song of a soldier's wife' ... [by] Phan Huy Ích".[32]

The song thất doublet is rarely used on its own — it is almost always paired with a lục bát couplet.[33] Whereas a series of linked song thất lục bát quatrains — or occasionally just a single quatrain — is the most usual form, other variations are possible. A sequence may begin with a lục bát couplet; in this case the sequence must still end with a lục bát. Alternatively, song thất doublets may be randomly interspersed within a long lục bát poem.[33] Poets occasionally vary the form; for example, for variety the final syllable of an "eight" line may rhyme with the 3rd — instead of the 5th — syllable of the initial "seven" line of the following quatrain.

Other verse forms

Stanzas defined only by end-rhyme include:

- ABAB (alternate rhyme, analogous to the Sicilian quatrain, or Common measure)

- xAxA (intermittent rhyme, analogous to many of the English and Scottish Ballads) Additional structure may be provided by the final syllables of odd lines ("x") being in the opposite tone class to the rhyming ones, creating a tone class scheme (though not a rhyme scheme) of ABAB.

- ABBA (envelope rhyme, analogous to the "In Memoriam" stanza) In this stanza, if the "A" rhyme is sharp, then the "B" rhyme is flat, and vice versa.

- AAxA (analogous to the Rubaiyat stanza)

- Couplets, in which flat couplets and sharp couplets alternate (for example Xuân Diệu's Tương Tư Chiều):

Bữa nay lạnh mặt trời đi ngủ sớm, Anh nhớ em, em hỡi! Anh nhớ em. A (flat rhyme) Không gì buồn bằng những buổi chiều êm, A (flat rhyme) Mà ánh sáng đều hòa cùng bóng tối. B (sharp rhyme) Gió lướt thướt kéo mình qua cỏ rối; B (sharp rhyme) Vài miếng đêm u uất lẩn trong cành; C (flat rhyme) Mây theo chim về dãy núi xa xanh C (flat rhyme) Từng đoàn lớp nhịp nhàng và lặng lẽ. D (sharp rhyme) Không gian xám tưởng sắp tan thành lệ.[34] D (sharp rhyme)

A poem in serial rhyme exhibits the same rhyme at the end of each line for an indefinite number of lines, then switches to another rhyme for an indefinite period. Within rhyming blocks, variety can be achieved by the use of both rich and poor rhyme.

Four syllable poetry

If second syllable is flat rhyme then the fourth syllable is sharp rhyme

Line number Rhyme 1 T B 2 B T Word number 1 2 3 4

Bão đến ầm ầm

Như đoàn tàu hỏa[35]

The converse is true

Line number Rhyme 1 B T 2 T B Syllable number 1 2 3 4

Chim ngoài cửa sổ

Mổ tiếng võng kêu[36]

However a lot of poems do not conform to the above rule:

Bão đi thong thả

Như con bò gầy

Five-syllable poetry

Similar to four-syllable poetry, it also has its own exceptions.

Hôm nay đi chùa Hương

Hoa cỏ mờ hơi sương

Cùng thầy me em dậy

Em vấn đầu soi gương[37]

Six syllable poetry

Using the last syllable, với cách with rhyme rule like vần chéo or vần ôm:

- Vần chéo

Quê hương là gì hở mẹ

Mà cô giáo dạy phải yêu

Quê hương là gì hở mẹ

Ai đi xa cũng nhớ nhiều

- Đỗ Trung Quân - Quê Hương

- Vần ôm

Xuân hồng có chàng tới hỏi:

-- Em thơ, chị đẹp em đâu?

-- Chị tôi tóc xõa ngang đầu

Đi bắt bướm vàng ngoài nội

- Huyền Kiêu - Tình sầu

Seven syllable poetry

The influence of Seven syllable, four line in Tang poetry can still be seen in the rhyme rule of seven-syllable poetry. 2 kinds of line:

- Flat Rhyme

Line number Rhyme 1 B T B B 2 T B T B 3 T B T T 4 B T B B Syllable number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Quanh năm buôn bán ở mom sông

Nuôi đủ năm con với một chồng

Lặn lội thân cò khi quãng vắng

Eo sèo mặt nước buổi đò đông[38]

Or more recently

Em ở thành Sơn chạy giặc về

Tôi từ chinh chiến cũng ra đi

Cách biệt bao ngày quê Bất Bạt

Chiều xanh không thấy bóng Ba Vì

- Quang Dũng - Đôi Mắt Người Sơn Tây

- Sharp Rhyme

Line number Rhyme 1 T B T B 2 B T B B 3 B T B T 4 T B T B Syllable number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Lẳng lặng mà nghe nó chúc nhau:

Chúc nhau trăm tuổi bạc đầu râu

Phen này ông quyết đi buôn cối

Thiên hạ bao nhiêu đứa giã trầu[39]

Recently this form has been modified to be:

Line number Rhyme 1 B T B 2 T B T Syllable number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Ta về cúi mái đầu sương điểm

Nghe nặng từ tâm lượng đất trời

Cảm ơn hoa đã vì ta nở

Thế giới vui từ mỗi lẻ loi

- Tô Thùy Yên - Ta về

Eight-syllable poetry

This form of poetry has no specified rule, or free rhyme. Usually if:

- The last line has sharp rhyme then word number three is sharp rhyme, syllable number five and six are flat rhyme

Rhyme T B B T Syllable number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

- The last line has flat rhyme then word number three is flat rhyme, word number five and six are sharp rhyme

Rhyme B T T B Syllable number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

But there are always exceptions.

Ca dao (folk poetry)

Ca dao[40] is a form of folk poetry that can be sung like other poems, and can be used to create folksongs. Ca dao is actually a Sino-Vietnamese term. In Folk Literature book, Dinh Gia Khanh noted: "In Confucius, chapter Nguy Phong, Article Vien Huu says: 'Tam chi uu huu, nga can tha dao'- or 'My heart is sad, I sing and dao.' Book Mao Truyen says 'Khúc hợp nhạc viết ca, đô ca viết dao'- or 'The song with background music to accompany the lyrics is called "ca", singing a cappella, or without background music is called "dao."'"

People used to call ca dao "phong dao" because the ca dao reflects the customs of each locality and era. Ca dao can consist of four-syllable lines, five-syllable lines, six-eight or two seven six eight, can be sung wholecloth, without the need to insert fillers like when people ngam the typical poetry. For example, take the following six-eights

Đường vô xứ Nghệ quanh quanh

Non xanh nước biếc như tranh họa đồ

Or:

Tốt gỗ hơn tốt nước sơn

Xấu người đẹp nết còn hơn đẹp người

Vietnamese ca dao is romantic writing that serves as a standard for romance poetry. The love of the labourers is expressed in ca dao in many aspects: romantic love, family love, love for the village, love for the fields, love for the work, love for nature. Ca dao is also an expression of people's intellectual struggle in society, or in meeting with nature. Hence, ca dao reflects the emotional life, and material life of humans, the awareness of working and manufacturing in the social, economic and political milieu in a particular historical period. For example, talking about self-control of "four virtues, three conformity", women lament in songs:

Thân em như hạt mưa sa

Hạt vào đài các, hạt ra ruộng cày

Because their fate is more often than not decided by others and they have almost no sense of self-determination, the bitterness is distilled into poem lines that are at once humorous and painful:

Lấy chồng chẳng biết mặt chồng

Đêm nằm mơ tưởng, nghĩ ông láng giềng

Romantic love in the rural area is a kind of love intimately connected to rice fields, to the villages. The love lines serve to remind the poets as well as their lovers:

Anh đi anh nhớ quê nhà

Nhớ canh rau muống, nhớ cà dầm tương

Nhớ ai dãi nắng dầm sương

Nhớ ai tát nước bên đường hôm nao!

The hard life, of "the buffalo followed by the plough" is also reflected in ca dao:

Trâu ơi, tao bảo trâu này

Trâu ra ngoài ruộng, trâu cày với ta

Cày cấy vốn nghiệp nông gia,

Ta đây trâu đấy, ai mà quản công...

A distinctive characteristic of ca dao is the form which is close to rhyme rule, but still elegant, flexible, simple and light-hearted. They are as simple as colloquial, gentle, succinct, yet still classic and expressive of deep emotions. A sad scene:

Sóng sầm sịch lưng chưng ngoài bể bắc,

Hạt mưa tình rỉ rắc chốn hàng hiên...

Or the longing, missing:

Gió vàng hiu hắt đêm thanh

Đường xa dặm vắng, xin anh đừng về

Mảnh trăng đã trót lời thề

Làm chi để gánh nặng nề riêng ai!

A girl, in the system of tao hon, who had not learned how to tidy her hair, had to get married, the man is indifferent seeing the wife as a child. But when she reached her adulthood, things

Lấy chồng tử thủa mười lăm

Chồng chê tôi bé, chẳng nằm cùng tôi

Đến năm mười tám, đôi mươi

Tối nằm dưới đất, chồng lôi lên giường

Một rằng thương, hai rằng thương

Có bốn chân giường, gãy một, còn ba!...

Ca dao is also used as a form to imbue experiences that are easy to remember, for example cooking experiences:

Con gà cục tác: lá chanh

Con lợn ủn ỉn: mua hành cho tôi

Con chó khóc đứng khóc ngồi:

Bà ơi! đi chợ mua tôi đồng riềng.

Classical forms of ca dao

Phú form

Phú means presenting, describing, for example about somebody or something to help people visualize the person or thing. For example:

Đường lên xứ Lạng bao xa

Cách một trái núi với ba quãng đồng

Ai ơi! đứng lại mà trông

Kìa núi Thành Lạc, kìa sông Tam Cờ.

Em chớ thấy anh lắm bạn mà ngờ

Bụng anh vẫn thẳng như tờ giấy phong...

Or to protest the sexual immorality and brutality of the reigning feudalism.

Em là con gái đồng trinh

Em đi bán rượu qua dinh ông nghè

Ông nghè sai lính ra ve..

"Trăm lạy ông nghè, tôi đã có con!".

- Có con thì mặc có con!

Thắt lưng cho giòn mà lấy chồng quan.

Tỉ form

Tỉ is to compare. In this form, ca dao does not directly say what it means to say as in the phu, but uses another image to compare, to create an indirect implication, or to send a covert message. For example:

Thiếp xa chàng như rồng nọ xa mây

Như con chèo bẻo xa cây măng vòiI am far away from you, just as a dragon away from the clouds

Like a cheo beo bird far from the mang voi plant.

Or

Gối mền, gối chiếu không êm

Gối lụa không mềm bằng gối tay em.Cotton pillow, bamboo pillow not soft

Silk pillow not as soft as your arm as my pillow.

Or

Ăn thì ăn những miếng ngon

Làm thì chọn việc cỏn con mà làmWhen you eat, you only eat the nice stuff

But when you work, you only choose the tiny task to do.

Or

Anh yêu em như Bác Hồ yêu nước

Mất em rồi như Pháp mất Đông DươngI love you like Uncle Ho loves the country

When I lose you, it feels like the French lose Indochina

Hứng form

Hứng (inspiration) originates from emotions, which can give rise to happy feelings or sad ones, to see externality inspires hung, making people want to express their feelings and situations.

Trên trời có đám mây vàng

Bên sông nước chảy, có nàng quay tơ

Nàng buồn nàng bỏ quay tơ,

Chàng buồn chàng bỏ thi thơ học hành...

Or:

Gió đánh đò đưa, gió đập đò đưa,

Sao cô mình lơ lửng mà chưa có chồng...

Six-eight

According to Vũ Ngọc Phan, Ngưyễn Can Mộng:[41]

Rhymed verses in Vietnam are born of provers, then phong dao becoming melody, and chuong that can be sung. Six-eight literature, or two-seven all originate from here. The history of collecting and compiling proverbs, folk poetry and songs only started about 200 years ago. In the mid-eighteenth century, Tran Danh An (hieu Lieu Am) compiled Quốc phong giải trào and Nam phong nữ ngạn thi. These compilers copied proverbs, folk poetry by Chinese-transcribed Vietnamese words, then translated them to Chinese words and notes, meaning to compare Vietnam folk poetry with Quoc Phong poems in Confucian odes of China.

At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, books about collected tuc ngu and ca dao written in Nom appear. Into the 20th century, books collecting these heritages written in quoc ngu (Roman script) appear. Hence, it can be said that the six-eight form originated from proverbs and folk poetry. Rhyme is the bolded word. For example, in The Tale of Kieu, when So Khanh tempted Kieu to elope with him out of lau xanh of Tu Ba:

- Đêm thu khắc lậu canh tàn[42]

- Gió cây trút lá, trăng ngàn ngậm gương

- Lối mòn cỏ nhợt mùi sương [43]

- Lòng quê[44] đi một bước đường một đau.

Six-eight is usually the first poetic inspiration, influencing many poets in their childhood. Through the lullaby of ca dao, or colloquial verses of adults. Like:

Cái ngủ mày ngủ cho ngoan

Để mẹ đi cấy đồng xa trưa về

Bắt được con cá rô trê

Thòng cổ mang về cho cái ngủ ăn

Due to the gentle musical quality of six-eight, this form of poetry is often used in poems as a refrain, a link or connection, from rough to smooth, gentle as if sighing or praising. For instance in the Tiếng Hát Sông Hương by Tố Hữu

Trên dòng Hương-giang

Em buông mái chèo

Trời trong veo

Nước trong veo

Em buông mái chèo

Trên dòng Hương-giang

Trăng lên trăng đứng trăng tàn

Đời em ôm chiếc thuyền nan xuôi dòng

Or Trần Đăng Khoa in epic[45] Khúc hát người anh hùng

Cô Bưởi lắng nghe tiếng gà rừng rực

Thấy sức triệu người hồi sinh trong lồng ngực

Và cô đi

Bên đám cháy

Chưa tàn

Lửa hát rằng:

Quê tôi - những cánh rừng hoang

Chính trong cơn bão đại ngàn - tôi sinh

Nuôi tôi trong bếp nhà gianh

Ủ là một chấm - thổi thành biển khơi...

Free poetry movement

The Vietnamese "free poetry" movement may have started from the poems translated from French by Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, such as La Cigale et la Fourmi (from the fables of Jean de La Fontaine) in Trung Bắc Tân văn (1928).

Ve sầu kêu ve ve

Suốt mùa hè

Đến kỳ gió bấc thổi

Nguồn cơn thật bối rối.

Poetry with no prosody, no rule, no limits on the number of words in the line, no line limits, appears to have been more adapted to a mass audience. .[46]

With the free poetry using the "dong gay" technique, presenting long lines and short, to create a visual rhythm, when read aloud, not according to line but to sentence, with the aim to hear properly the sound of each word. Visual rhythm is the most important thing, because through it, the reader can follow the analytic process to figure out the meaning of the poem. The word "free" can be understood as the escape from the restraint of poetry rules. The poets want to chase after his inspirations and emotions, using words to describe inner feelings instead of being constrained by words, by rules. They do not have to be constrained by criticism until they have to change the words, ideas until the poem becomes a monster child of their emotions. For example, in Lưu Trọng Lư 'sTiếng thu

Năm vừa rồi

Chàng cùng tôi

Nơi vùng giác mộ

Trong gian nhà cỏ

Tôi quay tơ

Chàng ngâm thơ

Vườn sau oanh giục giã

Nhìn ra hoa đua nở

Dừng tay tôi kêu chàng...

Này, này! Bạn! Xuân sang

Chàng nhìn xuân mặt hớn hở

Tôi nhìn chàng, long vồn vã...

Rồi ngày lại ngày

Sắc màu: phai

Lá cành: rụng

Ba gian: trống

Xuân đi

Chàng cũng đi

Năm nay xuân còn trở lại

Người xưa không thấy tới

Xuân về.[47]

which later becomes Hữu Thỉnh trong bài Thơ viết ở biển:

Anh xa em

Trăng cũng lẻ

Mặt trời cũng lẻ

Biển vẫn cậy mình dài rộng thế

Vắng cánh buồm một chút

đã cô đơn

Gió không phải là roi mà vách núi phải mòn

Em không phải là chiều mà nhuộm anh đến tím

Sông chẳng đi đến đâu

nếu không đưa em đến

Dù sóng đã làm anh

Nghiêng ngả

Vì em<ref>Trích trong Tuyển tập thơ Tình bạn, tình yêu thơ - Nhà xuất bản giáo dục 1987</ref>

Poetical devices

The musical nature of Vietnamese poetry manifests in the use of onomatopoeic words like "ri rao" (rustling), "vi vut" (whistling), "am am" (banging), "lanh canh" (tinkling), etc. Word play abounds in Vietnamese poetry.

Imagery, or the use of words to create images, is another fundamental aspect of Vietnamese poetry. An example of imagery can be found in the national epic poem, The Tale of Kieu by Nguyễn Du (1765–1820):[48]

Cỏ non xanh tận chân trời

Cành lê trắng điểm một vài bông hoa

Due to the influence of the concept of visual arts in the times of the poet, Nguyễn Du usually employs "scenery description" style in his poems. Simple scenery, accentuated at certain points, gently sketched but irresistible. Another line by Bà Huyện Thanh Quan

Lom khom dưới núi tiều vài chú

Lác đác bên sông chợ mấy nhà

Or Nguyễn Khuyến:

Ao thu lạnh lẽo nước trong veo

Một chiếc thuyền câu bé tẻo teo

Sóng biếc theo làn hơi gợn tí

Lá vàng trước gió khẽ đưa vèo.

Or most recently Trần Đăng Khoa in Nghe thầy đọc thơ

Em nghe thầy đọc bao ngày

Tiếng thơ đỏ nắng, xanh cây quanh nhà

Mái chèo nghiêng mặt sông xa

Bâng khuâng nghe vọng tiếng bà năm xưa

These images are beautiful and tranquil, but they can also be non-static and lively. When objects are described in poetry, they are often personified. Using verbs for inanimate, insentient objects is akin to breathing life into the objects, making it lively in the mind of the reader. For instance, Tran Dang Khoa wrote in "Mặt bão":

Bão đến ầm ầm

Như đoàn tàu hỏa

Bão đi thong thả

Như con bò gầy

Or in Góc Hà Nội

Nắng tháng tư xỏa mặt

Che vội vàng nỗi nhớ đã ra hoa

...

Thành phố ngủ trong rầm rì tiếng gió

Nhà ai quên khép cửa

Giấc ngủ thôi miên cả bến tàu

Such lines contain metaphors and similes. Humorous metaphors are commonly seen in poetry written for children. Examples are these lines that Khoa wrote at 9 years old in Buổi sáng nhà em:

Ông trời nổi lửa đằng đông

Bà sân vấn chiếc khăn hồng đẹp thay

...

Chị tre chải tóc bên ao

Nàng mây áo trắng ghé vào soi gương

Bác nồi đồng hát bùng boong

Bà chổi loẹt quẹt lom khom trong nhà

However, these also appear in more mature poets’ work. For example, Nguyễn Mỹ in Con đường ấy:[49]

Nắng bay từng giọt - nắng ngân vang

Ở trong nắng có một ngàn cái chuông

Or Hàn Mặc Tử in Một Nửa Trăng

Hôm nay chỉ có nửa trăng thôi

Một nửa trăng ai cắn vỡ rồi

Particularly, the metaphors in Hồ Xuân Hương poetry causes the half-real, half-unreal state, as if teasing the reader as in "Chess"

Quân thiếp trắng, quân chàng đen,

Hai quân ấy chơi nhau đà đã lửa.

Thọat mới vào chàng liền nhảy ngựa,

Thiếp vội vàng vén phứa tịnh lên.

Hai xe hà, chàng gác hai bên,

Thiếp thấy bí, thiếp liền ghểnh sĩ.

Or in Ốc nhồi

Bác mẹ sinh ra phận ốc nhồi,

Đêm ngày lăn lóc đám cỏ hôi.

Quân tử có thương thì bóc yếm,

Xin đừng ngó ngoáy lỗ trôn tôi.

The "tứ" (theme) of a poem is the central emotion or image the poem wants to communicate. "Phong cách" (style) is the choice of words, the method to express ideas. Structure of the poetry is the form and the ideas of the poems combined together.

Điệu (rhythm)

Điệu (rhythm)[50] is created by the sounds of selected words and cadence of the lines. Music in the poetry is constituted by 3 elements: rhyme, cadence and syllabic sound. "Six-eight" folk song is a form of poetry rich in musical quality.

- Cadence of lines: Cadence refers to the tempo, rhythm of the poem, based on how the lines are truncated into verses, each verse with a complete meaning. It is "long cadence" when people stop and dwell on the sound when they recite the line. Besides, in each verse, when reciting impromptu, we can also stop to dwell on shorter sounds at verses separated into components, which is called "short cadence"

Dương gian (-) hé rạng (-) hình hài (--)

Trời (-) se sẽ lạnh (-), đất ngai (--) ngái mùi(--)

- Cadence in poetry, created by the compartmentalization of the line and the words, similar to putting punctuations in sentence, so we pause when we read Nhịp (4/4) - (2/2/2/2)

- Rhythm (4/4) - (2/2/2/2)

Em ngồi cành trúc (--) em tựa cành mai (--)

Đông đào (-) tây liễu (-) biết ai (-) bạn cùng (--)

- Rhythm (2/2/2) - (2/2/2/2)

Trời mưa (-) ướt bụi (-) ướt bờ (-)

Ướt cây (-) ướt lá (--) ai ngờ (-) ướt em (--)

- Rhythm (2/4) - (2/2/2/2)

Yêu mình (--) chẳng lấy được mình (--)

Tựa mai (-) mai ngã (--) tựa đình (-) đình xiêu (--)

- Rhythm (2/4) - (4/4)

Đố ai (-) quét sạch lá rừng (--)

Để ta khuyên gió (--) gió đừng rung cây (--)

- Rhythm (2/4) - (2/4/2)

Hỡi cô (-) tát nước bên đàng (--)

Sao cô (-) múc ánh trăng vàng (--) đổ đi (--)

- Rhythm (4/2) - (2/4/2)

Trách người quân tử (-) bạc tình (--)

Chơi hoa (--) rồi lại bẻ cành (--) bán rao (--)

- Rhythm (3/2/2) - (4/3/2)

Đạo vợ chồng (-) thăm thẳm (-) giếng sâu (--)

Ngày sau cũng gặp (--) mất đi đâu (-) mà phiền (--)

- Musical quality of words: according to linguistics, each simple word of Vietnamese is a syllable, which can be strong or weak, pure or muddled, depending on the position of the pronunciation in the mouth (including lips, air pipe and also the openness of the mouth) One word is pronounced at a position in the mouth is affected by 4 elements constituting it: vowel, first consonant, last consonant and tone. Hence words that have

- "up" vowel like : i, ê, e

- "resounding" consonant like: m, n, nh, ng

- "up sound" : level, sharp, asking tones

Then when the words get pronounced, the sound produced will be pure, high and up. On the other hand, words that have

- "down" vowel: u, ô, o,

- "dead-end" consonant: p, t, ch, c,

And "down" tone: hanging, tumbling and heavy tones then the word pronounced will be muddled and heavy

The purity of the words punctuate the line. Rhyming syllables are most essential to the musical quality of the poem.

Hôm qua (-) tát nước đầu đình (--)

Bỏ quên cái áo (-) Trên cành hoa sen (--)

Em được (--) thì cho anh xin (--)

Hay là (-) em để làm tin (-) trong nhà. (--)

Punctuating words and rhyming words in these lines generate a certain kind of echo and create a bright melody, all to the effect of portraying the bright innocence of the subject of the verse.

Nụ tầm xuân (-) nở ra xanh biếc. (--)

Em đã có chồng (--) anh tiếc (-) lắm thay. (--)

Sound "iếc" in the two words "biếc" và "tiếc" rhyming here has two "up" vowels (iê) together with up tone but rather truncated by the last consonant "c", are known as "clogged sound". These sounds, when read out loud, are associated with sobbing, hiccup, the music is thus slow, and plaintive, sorrowful. Hence, "iec" is particularly excellently rhymed, to express most precisely the heart-wrenching regret of the boy returning to his old place, meeting the old friends, having deep feelings for a very beautiful girl, but the girl was already married.

Yêu ai tha thiết, thiết tha

Áo em hai vạt trải ra chàng ngồi.

Sometimes to preserve the musical quality of the folklore poem, the sounds of the compound words can have reversal of positions. Like the above folklore, the two sounds "tha thiet" are reversed to become "thiet tha", because the 6-8 form of the poem only allows for flat rhyme. Poetry or folksongs often have "láy" words, whereby due to the repetition of the whole word or an element of it, "láy" word, when pronounced, two enunciations of the two words will coincide (complete "láy") or come close (incomplete "láy") creating a series of harmony, rendering the musical quality of poetry both multi-coloured and elegant.

Poetic riddles

Riddles

Like Ca Dao, folk poetry riddles, or Đố were anonymously composed in ancient times and passed down as a regional heritage. Lovers in courtship often used Đố as a challenge for each other or as a smart flirt to express their inner sentiments.[51] Peasants in the Red River and Mekong Deltas used Đố as entertainment to disrupt the humdrum routine of rice planting or after a day's toil. Đố satisfies the peasants' intellectual needs and allows them to poke fun at the pedantic court scholars, stumped by these equivocating verses. [52]

Mặt em phương tượng chữ điền,

Da em thì trắng, áo đen mặc ngoài.

Lòng em có đất, có trời,

Có câu nhân nghĩa, có lời hiếu trung.

Dù khi quân tử có dùng,

Thì em sẽ ngỏ tấm lòng cho xem.[53]

My face resembles the character of "rice field"

My skin is white, but I wear a black shield

My heart (lit. bowel) harbors the earth, the sky

Words about conscience and loyalty

When you gentleman could use for me,

I will open my heart for you to see

The speaker refers to herself as "em," an affectionate, if not somewhat sexist, pronoun for a subordinate, often a female. Combined with the reference to the rice field, the verses suggest that the speaker is of a humble position, most likely a lowly peasant girl. Pale skin is a mark of beauty, hence the speaker is also implying that she is a pretty girl. She is speaking to a learned young man, a scholar, for whom she has feelings. The answer to the riddle is that the "I" is a book. In a few verses, the clever speaker coyly puts forth a metaphorical self-introduction and proposal: a peasant girl with both physical and inner beauty invites the gentleman-scholar's courtship.

Rhyming Math Puzzles

Yêu nhau cau sáu bổ ba,

Ghét nhau cau sáu bổ ra làm mười.

Mỗi người một miếng trăm người,

Có mười bảy quả hỏi người ghét yêu.[54]

If we love each other, we will divide the areca nut into three wedges

If we hate each other, we will divide the areca nut into ten wedges

One wedge per person, a hundred of us

With seventeen nuts, how many haters and lovers have we?

With just four rhyming verses, the riddle sets up two linear equations with two unknowns. The answers are 30 lovers and 70 haters. The numbers might seem irrelevant to the overall context of a flirty math puzzle, but one may see the proportions as a representation of the romantic dynamics of the couple, or the speaker himself or herself: 3 part love, 7 part despair.

See also

- Censorship in Vietnam

- Classical Chinese poetry forms

- Tang poetry

- Vè

- Tale of Kiều

- Chinh phụ ngâm

- Confucian scholar poets Trần Tế Xương, Nguyễn Khuyến, Bà Huyện Thanh Quan, Hồ Xuân Hương

Notes

- Nguyen 1975, p xv.

- Nguyen 1975, p 3.

- Nguyen 1975, pp xvi-xvii.

- Durand & Nguyen 1985, p 7.

- Nguyen 1975, p xviii.

- Nguyen 1975, p 39.

- Nguyen 1975, pp 4-5.

- Nguyen 1975, pp 10-11.

- Nguyen 1975, pp xviii-xix.

- Nguyen 1975, p 69.

- NB: "Rhymed verse" designates a specific form of verse, and should not be taken to mean that earlier Vietnamese verse was unrhymed. These earlier forms, like the Chinese forms they were based on, were rhymed.

- Nguyen 1975, p 88.

- Nguyen 1975, pp 112-13.

- Nguyen 1975, pp 117-18.

- Nguyen 1975, pp xx-xxi, 159.

- Nguyen 1975, p xxi.

- extracted from Cung Oán Ngâm Khúc - Nguyễn Gia Thiều (1741- 1798) - Poetry compilation Tình bạn, tình yêu thơ - Education Publisher 1987

- Nguyễn Du: Truyện Kiều, lines 1519-20.

- Nguyễn Du: Truyện Kiều, lines 1523-24.

- Echols 1974, p 892.

- Phu Van 2012, p 1519.

- Huỳnh 1996, p 7.

- Liu 1962, p 27.

- Liu 1962, p 26.

- Liu 1962, p 29.

- Huỳnh 1996, pp 6-7.

- Huỳnh 1996, p 3.

- Huỳnh 1996, p 9.

- Huỳnh 1996, p 11.

- Huỳnh 1996, pp 10-11.

- Nguyễn Du: Truyện Kiều, lines 1-6.

- Huỳnh 1996, p 14.

- Huỳnh 1996, p 12.

- Xuân Diệu: Tương tư chiều, lines 1-9.

- Trích trong bài Mặt bão - Thơ Trần Đăng Khoa - Tác phẩm chọn lọc dành cho thiếu nhi - Nhà xuất bản Kim Đồng, 1999

- Trích trong bài Tiếng võng kêu - Thơ Trần Đăng Khoa - Tác phẩm chọn lọc dành cho thiếu nhi - Nhà xuất bản Kim Đồng, 1999

- Trích trong bài Chùa Hương của Nguyễn Nhược Pháp (1914-1938) - Tập thơ Mưa đèn cây - nhà xuất bản phụ nữ - 1987

- Trích bài Thương vợ - Trần Tế Xương (1871-1907) - Tuyển tập thơ Tình bạn, tình yêu thơ - Nhà xuất bản giáo dục 1987

- Trích bài Chúc Tết - Trần Tế Xương (1871-1907)- Tuyển tập thơ Tình bạn, tình yêu thơ - Nhà xuất bản giáo dục 1987

- Trích trong Tục ngữ ca dao dân ca Việt Nam, Vũ Ngọc Phan, nhà xuất bản Khoa học Xã hội Hà Nội - 1997

- Nguyễn Can Mộng, (hiệu: Nông Sơn; 1880 - 1954), who wrote Ngạn ngữ phong dao

- Khắc lậu: ám chỉ cái khắc ở trên đồng hồ treo mặt nước chảy đi từng giọt mà sứt xuống; canh tành là gần sáng.

- Cảnh đêm mùa thu - Nhợt là cỏ có sương bám vào, mùi nhời nhợt, chẳng hạn: Lối mòn lướt mướt hơi sương

- Lòng quê: Lòng riêng, nghĩ riêng trong bụng.

- Trường ca là một tác phẩm dài bằng thơ có nội dung và ý nghĩa xã hội rộng lớn. - Đại từ điển tiếng Việt - Nguyễn Như Ý chủ biên, NXB Văn hóa – Thông tin, Hà Nội 1998

- Trích trong Phê Bình Văn Học Thế Hệ 1932 - Chim Việt Cành Nam

- Trích trong bài Phong trào thơ mới 1930-1945

- Nguyễn Du, Kiều Nhà xuất bản Thanh Niên, 1999

- Tập thơ Mưa đèn cây - nhà xuất bản phụ nữ - 1987

- Trích trong bài của Trần Ngọc Ninh

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://ecadao.com/tieuluan/caudo/caudo.htm%5B%5D

- Tục Ngữ - Phong Dao. Nguyễn Văn Ngọc. (Mặc Lâm. Yiễm Yiễm Thư Quán. Sàigòn 1967

- Nguyễn Trọng Báu - (Giai thoại chữ và nghĩa)

References

- Durand, Maurice M.; Nguyen Tran Huan (1985) [1969], An Introduction to Vietnamese Literature, Translated by D. M. Hawke, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-05852-7

- Echols, John M. (1974), "Vietnamese Poetry", in Preminger, Alex; Warnke, Frank J.; Hardison, O. B. (eds.), The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Enlarged ed.), Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 892–893, ISBN 0-691-01317-9

- Huỳnh Sanh Thông (1996), "Introduction", An Anthology of Vietnamese Poems: from the Eleventh through the Twentieth Centuries, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 1–25, ISBN 0-300-06410-1

- Liu, James J. Y. (1962), The Art of Chinese Poetry, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-48687-7

- Nguyen, Dinh-Hoa (1993), "Vietnamese Poetry", in Preminger, Alex; Brogan, T.V.F. (eds.), The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, New York: MJF Books, pp. 1356–1357, ISBN 1-56731-152-0

- Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1975), A Thousand Years of Vietnamese Poetry, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 0-394-49472-5

- Phu Van, Q. (2012), "Poetry of Vietnam", in Greene, Roland; Cushman, Stephen (eds.), The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (fourth ed.), Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 1519–1521, ISBN 978-0-691-13334-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poetry. |

- Chinh Phụ Ngâm Khúc - ny Đoàn Thị Điểm (1705–1748), originally by Đặng Trần Côn (1715?-1745)

- Poetry book vi:Góc sân và khoảng trời by vi:Trần Đăng Khoa - Information and Culture Publisher - 1998

- vi:Proverbs and folk poetry and songs of Vietnam by vi:Vũ Ngọc Phan - Hanoi Social Science Publisher- 1997

- New poetry movement 1930 - 1945

- GardenDigest.com, Extractions of commentary of poetry - by Michael P. Garofalo

- Evan.com, The 6th Poetry Day in Việt Nam, 2008 at Văn Miếu-Quốc Tử Giám

- Tu van huong nghiep 1930 - 1945