Bangalore

Bangalore /bæŋɡəˈlɔːr/, officially known as Bengaluru[11] ([ˈbeŋɡəɭuːɾu] (![]()

Bangalore | |

|---|---|

| Bengaluru | |

| |

| Nicknames: | |

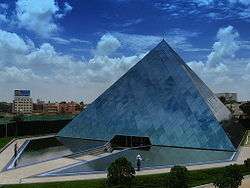

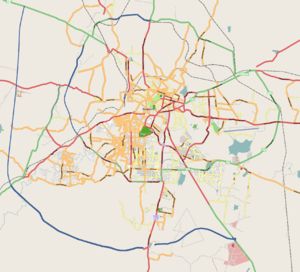

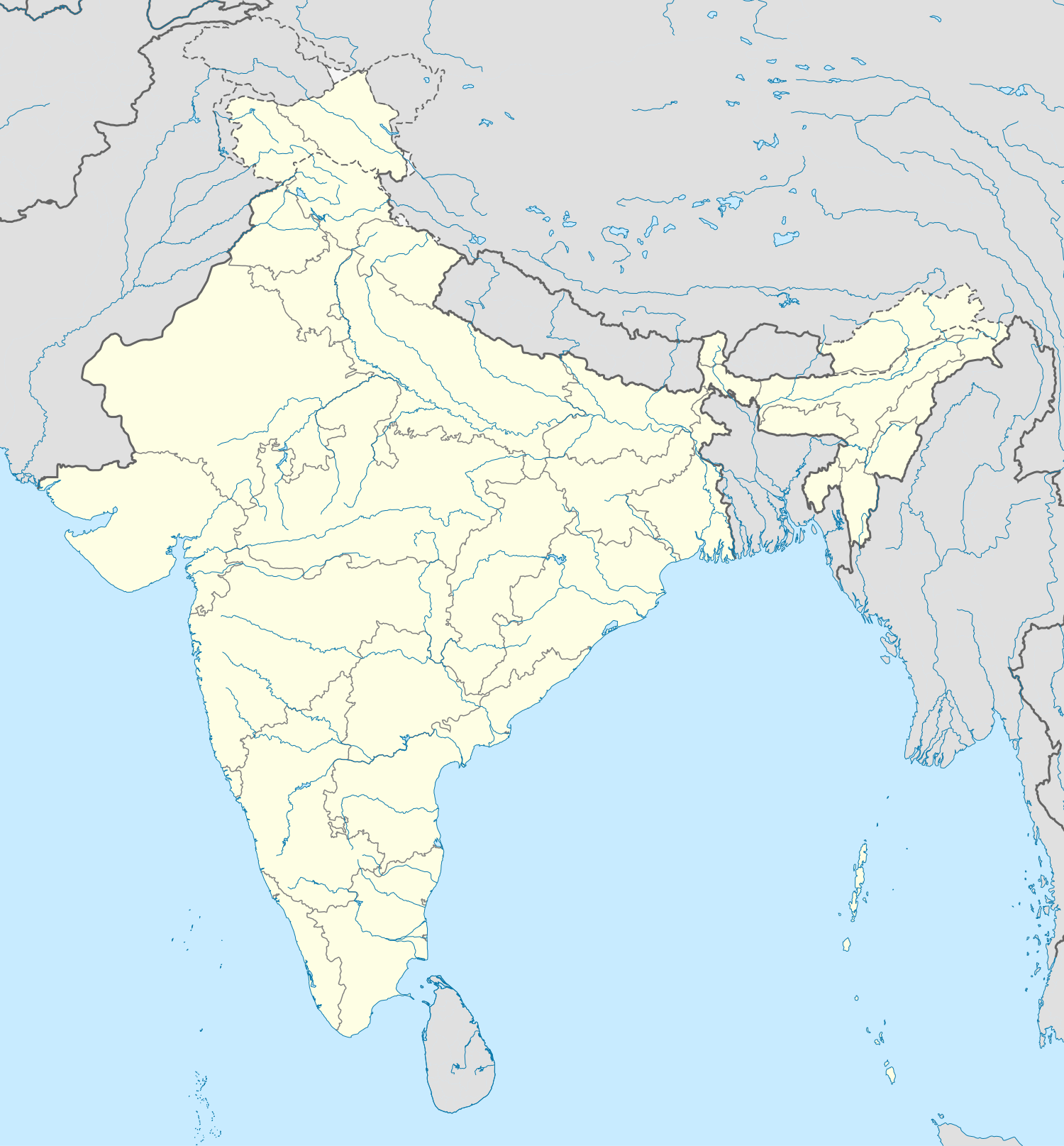

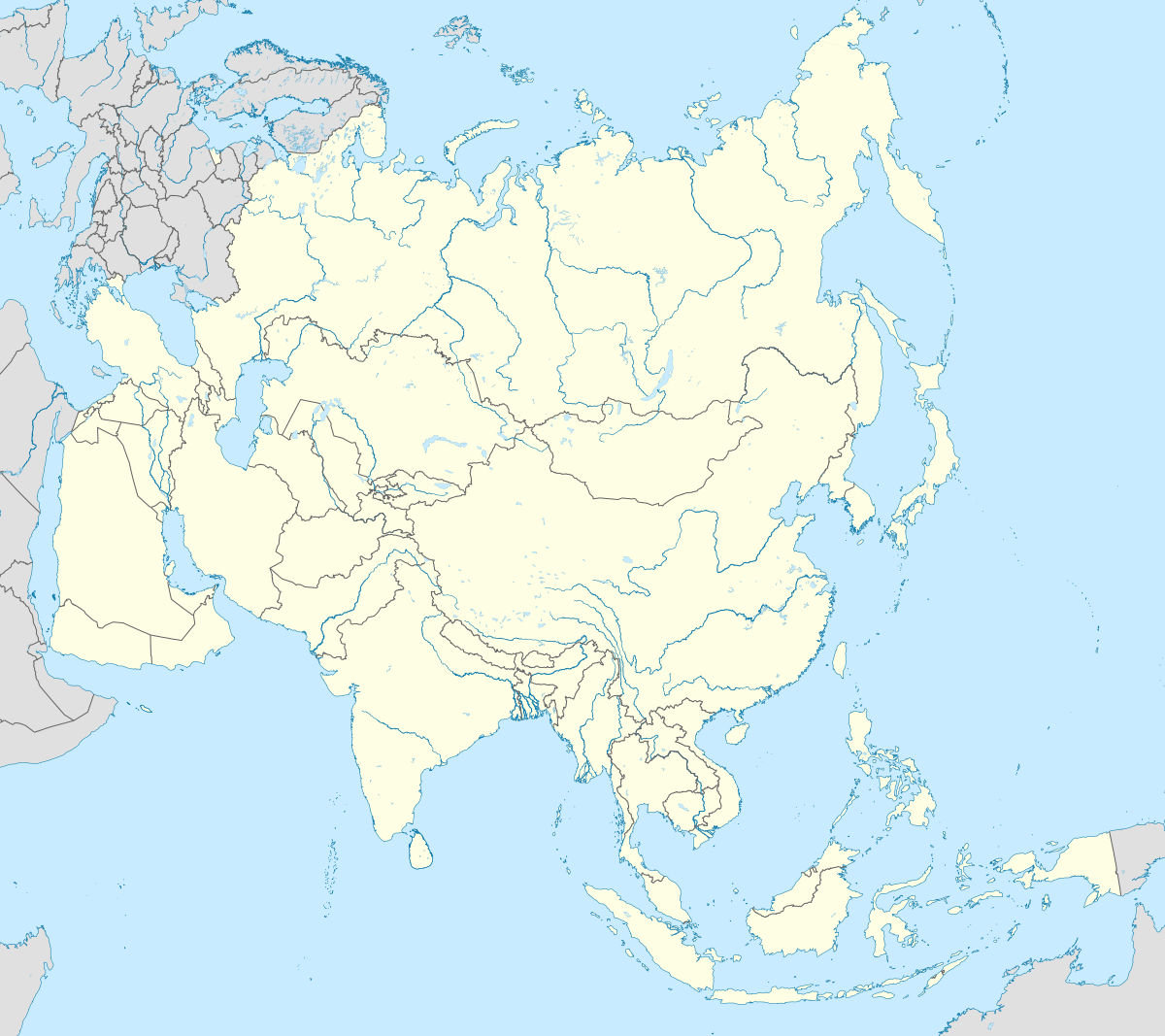

Bangalore Location of Bangalore in Karnataka, India  Bangalore Bangalore (Karnataka)  Bangalore Bangalore (India)  Bangalore Bangalore (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 12°59′N 77°35′E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Region | Bayaluseemé |

| District | Bangalore Urban |

| Established | 1537 |

| Founded by | Kempe Gowda I |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Body | Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike Bangalore Metropolitan Region Development Authority |

| • Mayor | M Goutham Kumar (BJP) |

| Area | |

| • Metropolis | 709 km2 (274 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 8,005 km2 (3,091 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 920 m (3,020 ft) |

| Population (2011)[6] | |

| • Metropolis | 8,443,675 |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| • Density | 12,000/km2 (31,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 10,456,000 |

| • Rank | 5th |

| Demonym(s) | Bangalorean, Bengalurinavaru, Bengalurean, Bengaluriga |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| Pincode(s) | 560 xxx |

| Area code(s) | +91-(0)80 |

| Vehicle registration | KA-01, 02, 03, 04, 05, 41, 50, 51, 52, 53, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 |

| Metro GDP | $45–$83 billion[9] |

| Official language | Kannada[10] |

| Website | www |

The city's history dates back to around 890 AD, in a stone inscription found at the Nageshwara Temple in Begur, Bangalore. The Begur inscription is written in Halegannada (ancient Kannada), mentions 'Bengaluru Kalaga' (battle of Bengaluru). It was a significant turning point in the history of Bangalore as it bears the earliest reference to the name 'Bengaluru'.[14] In 1537 CE, Kempé Gowdā – a feudal ruler under the Vijayanagara Empire – established a mud fort considered to be the foundation of modern Bengaluru and its oldest areas, or petes, which exist to the present day. After the fall of Vijayanagar empire in 16th century, the Mughals sold Bangalore to Chikkadevaraja Wodeyar (1673–1704), the then ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore for three lakh rupees.[15] When Haider Ali seized control of the Kingdom of Mysore, the administration of Bangalore passed into his hands. It was captured by the British East India Company after victory in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War (1799), who returned administrative control of the city to the Maharaja of Mysore. The old city developed in the dominions of the Maharaja of Mysore and was made capital of the Princely State of Mysore, which existed as a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj. In 1809, the British shifted their cantonment to Bangalore, outside the old city, and a town grew up around it, which was governed as part of British India. Following India's independence in 1947, Bangalore became the capital of Mysore State, and remained capital when the new Indian state of Karnataka was formed in 1956. The two urban settlements of Bangalore – city and cantonment – which had developed as independent entities merged into a single urban centre in 1949. The existing Kannada name, Bengalūru, was declared the official name of the city in 2006.

Bangalore is widely regarded as the "Silicon Valley of India" (or "IT capital of India") because of its role as the nation's leading information technology (IT) exporter.[1] Indian technological organisations such as ISRO, Infosys, Wipro and HAL are headquartered in the city. A demographically diverse city, Bangalore is the second fastest-growing major metropolis in India.[16] Recent estimates of the metro economy of its urban area have ranked Bangalore either the fourth or fifth-most productive metro area of India.[9][17] It is home to many educational and research institutions in India, such as Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Indian Institute of Management (Bangalore) (IIMB), International Institute of Information Technology, Bangalore (IIITB), National Institute of Fashion Technology, Bangalore, National Institute of Design, Bangalore (NID R&D Campus), National Law School of India University (NLSIU) and National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS). Numerous state-owned aerospace and defence organisations, such as Bharat Electronics, Hindustan Aeronautics and National Aerospace Laboratories are located in the city. The city also houses the Kannada film industry.

Etymology

The name "Bangalore" represents an anglicised version of the Kannada language name and its original name, "Bengalūru" ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು [ˈbeŋɡəɭuːru ] (![]()

An apocryphal story recounts that the twelfth century Hoysala king Veera Ballala II, while on a hunting expedition, lost his way in the forest. Tired and hungry, he came across a poor old woman who served him boiled beans. The grateful king named the place "benda-kaal-uru" (literally, "town of boiled beans"), which eventually evolved into "Bengalūru".[18][20][21] Suryanath Kamath has put forward an explanation of a possible floral origin of the name, being derived from benga, the Kannada term for Pterocarpus marsupium (also known as the Indian Kino Tree), a species of dry and moist deciduous trees, that grew abundantly in the region.[22]

On 11 December 2005, the Government of Karnataka announced that it had accepted a proposal by Jnanpith Award winner U. R. Ananthamurthy to rename Bangalore to Bengalūru.[23] On 27 September 2006, the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) passed a resolution to implement the proposed name change.[24] The government of Karnataka accepted the proposal, and it was decided to officially implement the name change from 1 November 2006.[25][26] The Union government approved this request, along with name changes for 11 other Karnataka cities, in October 2014, hence Bangalore was renamed to "Bengaluru" on 1 November 2014.[27][28]

History

Early and medieval history

A discovery of Stone Age artefacts during the 2001 census of India at Jalahalli, Sidhapura and Jadigenahalli, all of which are located on Bangalore's outskirts today, suggest probable human settlement around 4,000 BCE.[29] Around 1,000 BCE (Iron Age), burial grounds were established at Koramangala and Chikkajala on the outskirts of Bangalore. Coins of the Roman emperors Augustus, Tiberius, and Claudius found at Yeswanthpur and HAL indicate that the region was involved in trans-oceanic trade with the Romans and other civilizations in 27 BCE.[30]

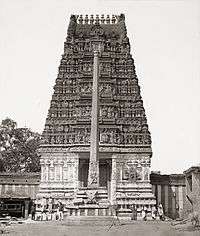

The region of modern-day Bangalore was part of several successive South Indian kingdoms. Between the fourth and the tenth centuries, the Bangalore region was ruled by the Western Ganga Dynasty of Karnataka, the first dynasty to set up effective control over the region.[31] According to Edgar Thurston[32] there were twenty-eight kings who ruled Gangavadi from the start of the Christian era until its conquest by the Cholas. These kings belonged to two distinct dynasties: the earlier line of the Solar race which had a succession of seven kings of the Ratti or Reddi tribe, and the later line of the Ganga race. The Western Gangas ruled the region initially as a sovereign power (350–550), and later as feudatories of the Chalukyas of Badami, followed by the Rashtrakutas until the tenth century.[22] The Begur Nageshwara Temple was commissioned around 860, during the reign of the Western Ganga King Ereganga Nitimarga I and extended by his successor Nitimarga II.[33][34] Around 1004, during the reign of Raja Raja Chola I, the Cholas defeated the Western Gangas under the command of the crown prince Rajendra Chola I, and captured Bangalore.[33][35] During this period, the Bangalore region witnessed the migration of many groups — warriors, administrators, traders, artisans, pastorals, cultivators, and religious personnel from Tamil Nadu and other Kannada speaking regions.[31] The Chokkanathaswamy temple at Domlur, the Aigandapura complex near Hesaraghatta, Mukthi Natheshwara Temple at Binnamangala, Choleshwara Temple at Begur, Someshwara Temple at Madiwala, date from the Chola era.[33]

In 1117, the Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana defeated the Cholas in the Battle of Talakad in south Karnataka, and extended its rule over the region.[33] Vishnuvardhana expelled the Cholas from all parts of Mysore state.[36] By the end of the 13th century, Bangalore became a source of contention between two warring cousins, the Hoysala ruler Veera Ballala III of Halebidu and Ramanatha, who administered from the Hoysala held territory in Tamil Nadu.[33] Veera Ballala III had appointed a civic head at Hudi (now within Bangalore Municipal Corporation limits), thus promoting the village to the status of a town. After Veera Ballala III's death in 1343, the next empire to rule the region was the Vijayanagara Empire, which itself saw the rise of four dynasties, the Sangamas (1336–1485), the Saluvas (1485–1491), the Tuluvas (1491–1565), and the Aravidu (1565–1646).[37] During the reign of the Vijayanagara Empire, Achyuta Deva Raya of the Tuluva Dynasty raised the Shivasamudra Dam across the Arkavati river at Hesaraghatta, whose reservoir is the present city's supply of regular piped water.[38]

Foundation and early modern history

Modern Bangalore was begun in 1537 by a vassal of the Vijayanagara Empire, Kempe Gowda I, who aligned with the Vijayanagara empire to campaign against Gangaraja (whom he defeated and expelled to Kanchi), and who built a mud-brick fort for the people at the site that would become the central part of modern Bangalore. Kempe Gowda was restricted by rules made by Achuta Deva Raya, who feared the potential power of Kempe Gowda and did not allow a formidable stone fort. Kempe Gowda referred to the new town as his "gandubhūmi" or "Land of Heroes".[21] Within the fort, the town was divided into smaller divisions—each called a "pete" (Kannada pronunciation: [peːteː]). The town had two main streets—Chikkapeté Street, which ran east–west, and Doddapeté Street, which ran north–south. Their intersection formed the Doddapeté Square—the heart of Bangalore. Kempe Gowda I's successor, Kempe Gowda II, built four towers that marked Bangalore's boundary. During the Vijayanagara rule, many saints and poets referred to Bangalore as "Devarāyanagara" and "Kalyānapura" or "Kalyānapuri" ("Auspicious City").[40]

After the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565 in the Battle of Talikota, Bangalore's rule changed hands several times. Kempe Gowda declared independence, then in 1638, a large Adil Shahi Bijapur army led by Ranadulla Khan and accompanied by his second in command Shāhji Bhōnslé defeated Kempe Gowda III,[40] and Bangalore was given to Shāhji as a jagir (feudal estate). In 1687, the Mughal general Kasim Khan, under orders from Aurangzeb, defeated Ekoji I, son of Shāhji, and sold Bangalore to Chikkadevaraja Wodeyar (1673–1704), the then ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore for three lakh rupees.[15] After the death of Krishnaraja Wodeyar II in 1759, Hyder Ali, Commander-in-Chief of the Mysore Army, proclaimed himself the de facto ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore. Hyder Ali is credited with building the Delhi and Mysore gates at the northern and southern ends of the city in 1760.[41] The kingdom later passed to Hyder Ali's son Tipu Sultan. Hyder and Tipu contributed towards the beautification of the city by building Lal Bagh Botanical Gardens in 1760. Under them, Bangalore developed into a commercial and military centre of strategic importance.[40]

The Bangalore fort was captured by the British armies under Lord Cornwallis on 21 March 1791 during the Third Anglo-Mysore War and formed a centre for British resistance against Tipu Sultan.[42] Following Tipu's death in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War (1799), the British returned administrative control of the Bangalore "pētē" to the Maharaja of Mysore and was incorporated into the Princely State of Mysore, which existed as a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj. The old city ("pētē") developed in the dominions of the Maharaja of Mysore. The Residency of Mysore State was first established in Mysore City in 1799 and later shifted to Bangalore in 1804. It was abolished in 1843 only to be revived in 1881 at Bangalore and to be closed down permanently in 1947, with Indian independence.[43] The British found Bangalore to be a pleasant and appropriate place to station their garrison and therefore moved their cantonment to Bangalore from Seringapatam in 1809 near Ulsoor, about 6 kilometres (4 mi) north-east of the city. A town grew up around the cantonment, by absorbing several villages in the area. The new centre had its own municipal and administrative apparatus, though technically it was a British enclave within the territory of the Wodeyar Kings of the Princely State of Mysore.[44] Two important developments which contributed to the rapid growth of the city, include the introduction of telegraph connections to all major Indian cities in 1853 and a rail connection to Madras, in 1864.[45]

Later modern and contemporary history

.jpg)

In the 19th century, Bangalore essentially became a twin city, with the "pētē", whose residents were predominantly Kannadigas and the cantonment created by the British.[46] Throughout the 19th century, the Cantonment gradually expanded and acquired a distinct cultural and political salience as it was governed directly by the British and was known as the Civil and Military Station of Bangalore. While it remained in the princely territory of Mysore, Cantonment had a large military presence and a cosmopolitan civilian population that came from outside the princely state of Mysore, including British and Anglo-Indians army officers.

Bangalore was hit by a plague epidemic in 1898 that claimed nearly 3,500 lives. The crisis caused by the outbreak catalysed the city's sanitation process. Telephone lines were laid to help co-ordinate anti-plague operations. Regulations for building new houses with proper sanitation facilities came into effect. A health officer was appointed and the city divided into four wards for better co-ordination. Victoria Hospital was inaugurated in 1900 by Lord Curzon, the then Governor-General of British India.[47] New extensions in Malleswaram and Basavanagudi were developed in the north and south of the pētē.[48] In 1903, motor vehicles came to be introduced in Bangalore.[49] In 1906, Bangalore became one of the first cities in India to have electricity from hydro power, powered by the hydroelectric plant situated in Shivanasamudra.[50] The Indian Institute of Science was established in 1909, which subsequently played a major role in developing the city as a science research hub.[51] In 1912, the Bangalore torpedo, an offensive explosive weapon widely used in World War I and World War II, was devised in Bangalore by British army officer Captain McClintock of the Madras Sappers and Miners.[52]

Bangalore's reputation as the "Garden City of India" began in 1927 with the Silver Jubilee celebrations of the rule of Krishnaraja Wodeyar IV. Several projects such as the construction of parks, public buildings and hospitals were instituted to improve the city.[2] Bangalore played an important role during the Indian independence movement. Mahatma Gandhi visited the city in 1927 and 1934 and addressed public meetings here.[30] In 1926, the labour unrest in Binny Mills due to demand by textile workers for payment of bonus resulted in lathi charging and police firing, resulting in the death of four workers, and several injuries.[53] In July 1928, there were notable communal disturbances in Bangalore, when a Ganesh idol was removed from a school compound in the Sultanpet area of Bangalore.[54] In 1940, the first flight between Bangalore and Bombay took off, which placed the city on India's urban map.[51]

After India's independence in August 1947, Bangalore remained in the newly carved Mysore State of which the Maharaja of Mysore was the Rajapramukh (appointed governor).[55] The "City Improvement Trust" was formed in 1945, and in 1949, the "City" and the "Cantonment" merged to form the Bangalore City Corporation. The Government of Karnataka later constituted the Bangalore Development Authority in 1976 to co-ordinate the activities of these two bodies.[56] Public sector employment and education provided opportunities for Kannadigas from the rest of the state to migrate to the city. Bangalore experienced rapid growth in the decades 1941–51 and 1971–81, which saw the arrival of many immigrants from northern Karnataka. By 1961, Bangalore had become the sixth largest city in India, with a population of 1,207,000.[40] In the decades that followed, Bangalore's manufacturing base continued to expand with the establishment of private companies such as MICO (Motor Industries Company), which set up its manufacturing plant in the city.

By the 1980s, it was clear that urbanisation had spilled over the current boundaries, and in 1986, the Bangalore Metropolitan Region Development Authority, was established to co-ordinate the development of the entire region as a single unit.[56] On 8 February 1981, a major fire broke out at Venus Circus in Bangalore, where more than 92 lives were lost, the majority of them being children.[57] Bangalore experienced a growth in its real estate market in the 1980s and 1990s, spurred by capital investors from other parts of the country who converted Bangalore's large plots and colonial bungalows into multi-storied apartments.[58] In 1985, Texas Instruments became the first multinational corporation to set up base in Bangalore. Other information technology companies followed suit and by the end of the 20th century, Bangalore had established itself as the Silicon Valley of India.[40] Today, Bangalore is India's third most populous city. During the 21st century, Bangalore has suffered terrorist attacks in 2008, 2010, and 2013.

Geography

Bangalore lies in the southeast of the South Indian state of Karnataka. It is in the heart of the Mysore Plateau (a region of the larger Precambrian Deccan Plateau) at an average elevation of 900 m (2,953 ft).[59]:8 It is located at 12.97°N 77.56°E and covers an area of 741 km2 (286 sq mi).[60] The majority of the city of Bangalore lies in the Bangalore Urban district of Karnataka and the surrounding rural areas are a part of the Bangalore Rural district. The Government of Karnataka has carved out the new district of Ramanagara from the old Bangalore Rural district.[61]

The topology of Bangalore is generally flat, though the western parts of the city are hilly. The highest point is Vidyaranyapura Doddabettahalli, which is 962 metres (3,156 feet) and is situated to the north-west of the city.[62] No major rivers run through the city, although the Arkavathi and South Pennar cross paths at the Nandi Hills, 60 kilometres (37 miles) to the north. River Vrishabhavathi, a minor tributary of the Arkavathi, arises within the city at Basavanagudi and flows through the city. The rivers Arkavathi and Vrishabhavathi together carry much of Bangalore's sewage. A sewerage system, constructed in 1922, covers 215 km2 (83 sq mi) of the city and connects with five sewage treatment centres located in the periphery of Bangalore.[63]

In the 16th century, Kempe Gowda I constructed many lakes to meet the town's water requirements. The Kempambudhi Kere, since overrun by modern development, was prominent among those lakes. In the earlier half of 20th century, the Nandi Hills waterworks was commissioned by Sir Mirza Ismail (Diwan of Mysore, 1926–41 CE) to provide a water supply to the city. The river Kaveri provides around 80% of the total water supply to the city with the remaining 20% being obtained from the Thippagondanahalli and Hesaraghatta reservoirs of the Arkavathi river.[64] Bangalore receives 800 million litres (211 million US gallons) of water a day, more than any other Indian city.[65] However, Bangalore sometimes does face water shortages, especially during summer- more so in the years of low rainfall. A random sampling study of the air quality index (AQI) of twenty stations within the city indicated scores that ranged from 76 to 314, suggesting heavy to severe air pollution around areas of traffic concentration.[66]

Bangalore has a handful of freshwater lakes and water tanks, the largest of which are Madivala tank, Hebbal lake, Ulsoor lake, Yediyur Lake and Sankey Tank. Groundwater occurs in silty to sandy layers of the alluvial sediments. The Peninsular Gneissic Complex (PGC) is the most dominant rock unit in the area and includes granites, gneisses and migmatites, while the soils of Bangalore consist of red laterite and red, fine loamy to clayey soils.[66]

Vegetation in the city is primarily in the form of large deciduous canopy and minority coconut trees. Though Bangalore has been classified as a part of the seismic zone II (a stable zone), it has experienced quakes of magnitude as high as 4.5.[67]

Climate

Bangalore has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw) with distinct wet and dry seasons. Due to its high elevation, Bangalore usually enjoys a more moderate climate throughout the year, although occasional heat waves can make summer somewhat uncomfortable.[68] The coolest month is January with an average low temperature of 15.1 °C (59.2 °F) and the hottest month is April with an average high temperature of 35 °C (95 °F).[69] The highest temperature ever recorded in Bangalore is 39.2 °C (103 °F) (recorded on 24 April 2016) as there was a strong El Nino in 2016 [70] There were also unofficial records of 41 °C (106 °F) on that day. The lowest ever recorded is 7.8 °C (46 °F) in January 1884.[71][72] Winter temperatures rarely drop below 14 °C (57 °F), and summer temperatures seldom exceed 36 °C (97 °F). Bangalore receives rainfall from both the northeast and the southwest monsoons and the wettest months are September, October and August, in that order.[69] The summer heat is moderated by fairly frequent thunderstorms, which occasionally cause power outages and local flooding. Most of the rainfall occurs during late afternoon/evening or night and rain before noon is infrequent. November 2015 (290.4 mm) was recorded as one of the wettest months in Bangalore with heavy rains causing severe flooding in some areas, and closure of a number of organisations for over a couple of days.[73] The heaviest rainfall recorded in a 24-hour period is 179 millimetres (7 in) recorded on 1 October 1997.[74]

| Climate data for Bangalore (1981–2010, extremes 1901–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.8 (91.0) |

35.9 (96.6) |

37.3 (99.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.9 (102.0) |

38.1 (100.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27.9 (82.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

33.1 (91.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.3 (91.9) |

29.6 (85.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.8 (46.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 1.9 (0.07) |

5.4 (0.21) |

18.5 (0.73) |

41.5 (1.63) |

107.4 (4.23) |

106.5 (4.19) |

112.9 (4.44) |

147.0 (5.79) |

212.8 (8.38) |

168.3 (6.63) |

48.9 (1.93) |

15.7 (0.62) |

986.9 (38.85) |

| Average rainy days | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 8.3 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 58.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 41 | 32 | 29 | 35 | 47 | 62 | 65 | 67 | 64 | 65 | 61 | 53 | 52 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 262.3 | 247.6 | 271.4 | 257.0 | 241.1 | 136.8 | 111.8 | 114.3 | 143.6 | 173.1 | 190.2 | 211.7 | 2,360.9 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department[75][76] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun: 1971–1990)[77] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Population Growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | %± | |

| 1941 | 406,760 | — | |

| 1951 | 778,977 | 91.5% | |

| 1961 | 1,207,000 | 54.9% | |

| 1971 | 1,654,000 | 37.0% | |

| 1981 | 2,922,000 | 76.7% | |

| 1991 | 4,130,000 | 41.3% | |

| 2001 | 5,101,000 | 23.5% | |

| 2011 | 8,425,970 | 65.2% | |

| Source: Census of India[78][79] | |||

With a population of 8,443,675 in the city and 10,456,000 in the urban agglomeration,[7][6] up from 8.5 million at the 2011 census,[80] Bangalore is a megacity, and the third-most-populous city in India and the 18th-most-populous city in the world.[81] Bangalore was the fastest-growing Indian metropolis after New Delhi between 1991 and 2001, with a growth rate of 38% during the decade. Residents of Bangalore are referred to as "Bangaloreans" in English and Bengaloorinavaru or Bengaloorigaru in Kannada. People from other states have migrated to Bangalore.[82]

According to the 2011 census of India, 78.9% of Bangalore's population is Hindu, a little less than the national average.[83] Muslims comprise 13.9% of the population, roughly the same as their national average. Christians and Jains account for 5.6% and 1.0% of the population, respectively, double that of their national averages. The city has a literacy rate of 89%.[84] Roughly 10% of Bangalore's population lives in slums.[85]—a relatively low proportion when compared to other cities in the developing world such as Mumbai (50%) and Nairobi (60%).[86] The 2008 National Crime Records Bureau statistics indicate that Bangalore accounts for 8.5% of the total crimes reported from 35 major cities in India which is an increase in the crime rate when compared to the number of crimes fifteen years ago.[87]

Bangalore suffers from the same major urbanisation problems seen in many fast-growing cities in developing countries: rapidly escalating social inequality, mass displacement and dispossession, proliferation of slum settlements, and epidemic public health crisis due to severe water shortage and sewage problems in poor and working-class neighbourhoods.[88]

Official language of Bangalore is Kannada. Other languages such as English, Telugu, Tamil, Hindi, Malayalam, Urdu are also spoken widely.[89] The Kannada language spoken in Bangalore is a form of Kannada called as 'Old Mysuru Kannada' which is also used in most of the southern part of Karnataka state. A vernacular dialect of this, known as Bangalore Kannada, is spoken among the youth in Bangalore and the adjoining Mysore regions.[90] English (as an Indian dialect) is extensively spoken and is the principal language of the professional and business class.[91]

The major communities of Bangalore who share a long history in the city other than the Kannadigas are the Telugus and Tamilians, who migrated to Bangalore in search of a better livelihood.[92][93][94] Already in the 16th century, Bangalore had few speakers of Tamil and Telugu, who spoke Kannada to carry out low profile jobs. However the Telugu Speaking Morasu Vokkaligas are the native people of Bangalore[95] Telugu-speaking people initially came to Bangalore on invitation by the Mysore royalty (a few of them have lineage dating back to Krishnadevaraya).[96]

Other native communities are the Tuluvas and the Konkanis of coastal Karnataka, the Kodavas of the Kodagu district of Karnataka. The migrant communities are Maharashtrians, Punjabis, Rajasthanis, Gujaratis, Tamilians, Telugus, Malayalis, Odias, Sindhis, and Bengalis.[92] Bangalore once had a large Anglo-Indian population, the second largest after Calcutta. Today, there are around 10,000 Anglo-Indians in Bangalore.[97] Bangalorean Christians are principally migrants of Roman Catholic and Protestant traditions, constituted by Tamil Christians, Mangalorean Christians, Kannadiga Christians, Malayali Syrian Christians and Northeast Indian Christians.[98][99][100] Muslims form a very diverse population, consisting of Dakhini and Urdu-speaking Muslims, Kutchi Memons, Labbay and Mappilas.[101]

Languages

Kannada is the official language of Bengaluru, but the city is multi-cultural. According to census 2011, Kannada spoken by 46%, Tamil spoken by 13.99%, Telugu spoken by 13.89%, Urdu spoken by 12%, Hindi spoken by 5.4%, Malayalam spoken by 2.8%, Marathi spoken by 1.8%, Konkani spoken by 0.67%, Bengali spoken by 0.64%, Odia spoken by 0.52%, Tulu spoken by 0.49%, Gujarati spoken by 0.47% and Other languages spoken by 1.33%.[102]

Civic administration

| Important officials of Bangalore | |

|---|---|

| Municipal Commissioner: | BH Anil Kumar |

| Mayor: | M Goutham Kumar |

| Police Commissioner: | Kamal Pant, IPS |

Management

The Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP, Greater Bangalore Municipal Corporation) is in charge of the civic administration of the city. It was formed in 2007 by merging 100 wards of the erstwhile Bangalore Mahanagara Palike, with seven neighbouring City Municipal Councils, one Town Municipal Council and 110 villages around Bangalore. The number of wards increased to 198 in 2009.[103][104] The BBMP is run by a city council composed of 250 members, including 198 corporators representing each of the wards of the city and 52 other elected representatives, consisting of members of Parliament and the state legislature. Elections to the council are held once every five years, with results being decided by popular vote. Members contesting elections to the council usually represent one or more of the state's political parties. A mayor and deputy mayor are also elected from among the elected members of the council.[105] Elections to the BBMP were held on 28 March 2010, after a gap of three and a half years since the expiry of the previous elected body's term, and the Bharatiya Janata Party was voted into power – the first time it had ever won a civic poll in the city.[106] Indian National Congress councillor Sampath Raj became the city's mayor in September 2017, the vote having been boycotted by the BJP.[107] In September 2018, Indian National Congress councillor Gangambike Mallikarjun was elected as the mayor of Bangalore[108] and took charge from the outgoing mayor, Sampath Raj. In 2019 BJP’s M Goutham Kumar took charge as mayor.

Bangalore's rapid growth has created several problems relating to traffic congestion and infrastructural obsolescence that the Bangalore Mahanagara Palike has found challenging to address. The unplanned nature of growth in the city resulted in massive traffic gridlocks that the municipality attempted to ease by constructing a flyover system and by imposing one-way traffic systems. Some of the flyovers and one-ways mitigated the traffic situation moderately but were unable to adequately address the disproportionate growth of city traffic.[109] A 2003 Battelle Environmental Evaluation System (BEES) evaluation of Bangalore's physical, biological and socioeconomic parameters indicated that Bangalore's water quality and terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems were close to ideal, while the city's socioeconomic parameters (traffic, quality of life) air quality and noise pollution scored poorly.[110] The BBMP works in conjunction with the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) and the Agenda for Bangalore's Infrastructure and Development Task Force (ABIDe) to design and implement civic and infrastructural projects.[111]

The Bangalore City Police (BCP) has seven geographic zones, includes the Traffic Police, the City Armed Reserve, the Central Crime Branch and the City Crime Record Bureau and runs 86 police stations, including two all-women police stations.[112] Other units within the BCP include Traffic Police, City Armed Reserve (CAR), City Special Branch (CSB), City Crime Branch (CCB) and City Crime Records Bureau (CCRB). As capital of the state of Karnataka, Bangalore houses important state government facilities such as the Karnataka High Court, the Vidhana Soudha (the home of the Karnataka state legislature) and Raj Bhavan (the residence of the governor of Karnataka). Bangalore contributes four members to the lower house of the Indian Parliament, the Lok Sabha, from its four constituencies: Bangalore Rural, Bangalore Central, Bangalore North, and Bangalore South,[113] and 28 members to the Karnataka Legislative Assembly.[114]

Electricity in Bangalore is regulated through the Bangalore Electricity Supply Company (BESCOM),[115] while water supply and sanitation facilities are provided by the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB).[116]

The city has offices of the Consulate General of Germany,[117] France,[118] Japan[119] Israel,[120] British Deputy High Commission,[121] along with honorary consulates of Ireland,[122] Finland,[123] Switzerland,[124] Maldives,[125] Mongolia, Sri Lanka and Peru.[126] It also has a trade office of Canada[127] and a virtual Consulate of the United States.[128]

Pollution control

Bangalore generates about 3,000 tonnes of solid waste per day, of which about 1,139 tonnes are collected and sent to composting units such as the Karnataka Composting Development Corporation. The remaining solid waste collected by the municipality is dumped in open spaces or on roadsides outside the city.[129] In 2008, Bangalore produced around 2,500 metric tonnes of solid waste, and increased to 5000 metric tonnes in 2012, which is transported from collection units located near Hesaraghatta Lake, to the garbage dumping sites.[130] The city suffers significantly with dust pollution, hazardous waste disposal, and disorganised, unscientific waste retrievals.[131] The IT hub, Whitefield region is the most polluted area in Bangalore.[132] Recently a study found that over 36% of diesel vehicles in the city exceed the national limit for emissions.[133]

Anil Kumar, Commissioner Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike BBMP, said: "The deteriorating Air Quality in cities and its impact on public health is an area of growing concern for city authorities. While much is already being done about collecting and monitoring air quality data, little focus has been given on managing the impacts that bad air quality is having on the health of citizens."[134]

Slums

According to a 2012 report submitted to the World Bank by Karnataka Slum Clearance Board, Bangalore had 862 slums from total of around 2000 slums in Karnataka. The families living in the slum were not ready to move into the temporary shelters.[135][136] 42% of the households migrated from different parts of India like Chennai, Hyderabad and most of North India, and 43% of the households had remained in the slums for over 10 years. The Karnataka Municipality, works to shift 300 families annually to newly constructed buildings.[137] One-third of these slum clearance projects lacked basic service connections, 60% of slum dwellers lacked complete water supply lines and shared BWSSB water supply.[135]

Waste management

Ιn 2012 Bangalore generated 2.1 million tonnes of Municipal Solid Waste (195.4 kg/cap/yr).[138] The waste management scenario in the state of Karnataka is regulated by the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) under the aegis of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) which is a Central Government entity. As part of their Waste Management Guidelines the government of Karnataka through the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) has authorised a few well-established companies to manage the biomedical waste and hazardous waste in the state of Karnataka.

Economy

Recent estimates of the economy of Bangalore's metropolitan area have ranged from $45 to $83 billion (PPP GDP), and have ranked it either fourth- or fifth-most productive metro area of India.[9] In 2014, Bangalore contributed US$45 billion, or 38 per cent of India's total IT exports.[139] As of 2017, IT firms in Bengaluru employ about 1.5 million employees in the IT and IT-enabled services sectors, out of nearly 4.36 million employees across India.[140]

With an economic growth of 10.3%, Bangalore is the second fastest-growing major metropolis in India,[141] and is also the country's fourth largest fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) market.[142] Forbes considers Bangalore one of "The Next Decade's Fastest-Growing Cities".[143] The city is the third largest hub for high-net-worth individuals and is home to over 10,000-dollar millionaires and about 60,000 super-rich people who have an investment surplus of ₹45 million (US$630,900) and ₹5 million (US$70,100) respectively.[144]

The headquarters of several public sector undertakings such as Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL), Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), National Aerospace Laboratories (NAL), Bharat Earth Movers Limited (BEML), Central Manufacturing Technology Institute (CMTI) and HMT (formerly Hindustan Machine Tools) are located in Bangalore. In June 1972 the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) was established under the Department of Space and headquartered in the city. Bangalore also houses several research and development centres for many firms such as ABB, Airbus, Bosch, Boeing, General Electric, General Motors, Google, Liebherr-Aerospace, Microsoft, Mercedes-Benz, Nokia, Oracle, Philips, Shell, Toyota and Tyco.

Bangalore is called as the Silicon Valley of India because of the large number of information technology companies located in the city which contributed 33% of India's ₹1,442 billion (US$20 billion) IT exports in 2006–07.[145] Bangalore's IT industry is divided into three main clusters – Software Technology Parks of India (STPI); International Tech Park, Bangalore (ITPB); and Electronics City. UB City, the headquarters of the United Breweries Group, is a high-end commercial zone.[146] Infosys and Wipro, India's third and fourth largest software companies are headquartered in Bangalore, as are many of the global SEI-CMM Level 5 Companies.

The growth of IT has presented the city with unique challenges. Ideological clashes sometimes occur between the city's IT moguls, who demand an improvement in the city's infrastructure, and the state government, whose electoral base is primarily the people in rural Karnataka. The encouragement of high-tech industry in Bangalore, for example, has not favoured local employment development, but has instead increased land values and forced out small enterprise.[147] The state has also resisted the massive investments required to reverse the rapid decline in city transport which has already begun to drive new and expanding businesses to other centres across India. Bangalore is a hub for biotechnology related industry in India and in the year 2005, around 47% of the 265 biotechnology companies in India were located here; including Biocon, India's largest biotechnology company.[148][149]

Transport

Air

Bangalore is served by Kempegowda International Airport (IATA: BLR, ICAO: VOBL), located at Devanahalli, about 40 kilometres (25 miles) from the city centre. It was formerly called Bangalore International Airport. The airport started operations from 24 May 2008 and is a private airport managed by a consortium led by the GVK Group. The city was earlier served by the HAL Airport at Vimanapura, a residential locality in the eastern part of the city.[150][151][152] The airport is third-busiest in India after Delhi and Mumbai in terms of passenger traffic and the number of air traffic movements (ATMs).[153] Taxis and air conditioned Volvo buses operated by BMTC connect the airport with the city.

Namma Metro (Rail)

A rapid transit system called the Namma Metro is being built in stages. Initially opened with the 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) stretch from Baiyappanahalli to MG Road in 2011,[154] phase 1 covering a distance of 42.30 kilometres (26.28 mi) for the north–south and east–west lines was made operational by June 2017.[155] Phase 2 of the metro covering 72.1 kilometres (44.8 mi) is under construction and includes two new lines along with the extension of the existing north–south and east–west lines.[156] There are also plans to extend the north–south line to the airport, covering a distance of 29.6 kilometres (18.4 mi). It is expected to be operational by 2021.[157]

Bangalore is a divisional headquarters in the South Western Railway zone of the Indian Railways. There are four major railway stations in the city: Krantiveera Sangolli Rayanna Railway Station, Bangalore Cantonment railway station, Yeshwantapur junction and Krishnarajapuram railway station, with railway lines towards Jolarpettai in the east, Chikballapur in the north-east, Guntakal in the north, Tumkur in the northwest, Hassan and Mangalore[158] in the west, Mysore in the southwest and Salem in the south. There is also a railway line from Baiyappanahalli to Vimanapura which is no longer in use. Though Bangalore has no commuter rail at present, there have been demands for a suburban rail service keeping in mind the large number of employees working in the IT corridor areas of Whitefield, Outer Ring Road and Electronics City.

The Rail Wheel Factory is Asia's second-largest manufacturer of wheel and axle for railways and is headquartered in Yelahanka, Bangalore.[159]

Road

Buses operated by Bengaluru Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC) are an important and reliable means of public transport available in the city.[161] While commuters can buy tickets on boarding these buses, BMTC also provides an option of a bus pass to frequent users.[161] BMTC runs air-conditioned luxury buses on major routes, and also operates shuttle services from various parts of the city to Kempegowda International Airport.[162] The BMTC also has a mobile app that provides real-time location of a bus using the global positioning system of the user's mobile device.[163] The Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation operates 6,918 buses on 6,352 schedules, connecting Bangalore with other parts of Karnataka as well as other neighbouring states. The main bus depots that KSRTC maintains are the Kempegowda Bus Station, locally known as "Majestic bus stand", where most of the out station buses ply from. Some of the KSRTC buses to Tamil Nadu, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh ply from Shantinagar Bus Station, Satellite Bus Station at Mysore Road and Baiyappanahalli satellite bus station.[164] BMTC and KSRTC were the first operators in India to introduce Volvo city buses and intracity coaches in India. Three-wheeled, yellow and black or yellow and green auto-rickshaws, referred to as autos, are a popular form of transport. They are metered and can accommodate up to three passengers. Taxis, commonly called City Taxis, are usually available, too, but they are only available on call or by online services. Taxis are metered and are generally more expensive than auto-rickshaws.[165]

An average of 1,250 vehicles are being registered daily in Bangalore RTOs. The total number of vehicles as on date are 44 lakh vehicles, with a road length of 11,000 kilometres (6,835 miles).[166]

Culture

Bangalore is known as the "Garden City of India" because of its greenery, broad streets and the presence of many public parks, such as Lal Bagh and Cubbon Park.[167] Bangalore is sometimes called as the "Pub Capital of India" and the "Rock/Metal Capital of India" because of its underground music scene and it is one of the premier places to hold international rock concerts.[168] In May 2012, Lonely Planet ranked Bangalore third among the world's top ten cities to visit.[169]

Bangalore is also home to many vegan-friendly restaurants and vegan activism groups, and has been named as India's most vegan-friendly city by PETA India.[170][171]

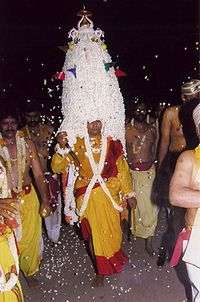

Biannual flower shows are held at the Lal Bagh Gardens during the week of Republic Day (26 January) and Independence Day (15 August). Bengaluru Karaga or "Karaga Shaktyotsava" is one of the most important and oldest festivals of Bangalore dedicated to the Hindu Goddess Draupadi. It is celebrated annually by the Thigala community, over a period of nine days in the month of March or April. The Someshwara Car festival is an annual procession of the idol of the Halasuru Someshwara Temple (Ulsoor) led by the Vokkaligas, a major land holding community in the southern Karnataka, occurring in April. Karnataka Rajyotsava is widely celebrated on 1 November and is a public holiday in the city, to mark the formation of Karnataka state on 1 November 1956. Other popular festivals in Bangalore are Ugadi, Ram Navami, Eid ul-Fitr, Ganesh Chaturthi, St. Mary's feast, Dasara, Deepawali and Christmas.[172][173]

The diversity of cuisine is reflective of the social and economic diversity of Bangalore.[174] Bangalore has a wide and varied mix of restaurant types and cuisines and Bangaloreans deem eating out as an intrinsic part of their culture. Roadside vendors, tea stalls, and South Indian, North Indian, Chinese and Western fast food are all very popular in the city.[175] Udupi restaurants are very popular and serve predominantly vegetarian, regional cuisine.[176]

Art and literature

Bangalore did not have an effective contemporary art representation, as compared to Delhi and Mumbai, until recently during the 1990s, several art galleries sprang up, notable being the government established National Gallery of Modern Art.[177] Bangalore's international art festival, Art Bangalore, was established in 2010.[178]

Kannada literature appears to have flourished in Bangalore even before Kempe Gowda laid the foundations of the city. During the 18th and 19th centuries, Kannada literature was enriched by the Vachanas (a form of rhythmic writing) composed by the heads of the Veerashaiva Mathas (monastery) in Bangalore. As a cosmopolitan city, Bangalore has also encouraged the growth of Telugu, Urdu, and English literatures. The headquarters of the Kannada Sahitya Parishat, a nonprofit organisation that promotes the Kannada language, is located in Bangalore.[179] The city has its own literary festival, known as the "Bangalore Literature Festival", which was inaugurated in 2012.[180]

Indian Cartoon Gallery

The cartoon gallery is located in the heart of Bangalore, dedicated to the art of cartooning, is the first of its kind in India. Every month the gallery is conducting fresh cartoon exhibition of various professional as well as amateur cartoonist. The gallery has been organised by the Indian Institute of Cartoonists based in Bangalore that serves to promote and preserve the work of eminent cartoonists in India. The institute has organised more than one hundred exhibitions of cartoons.[181][182]

Theatre, music, and dance

Bangalore is home to the Kannada film industry, which churns out about 80 Kannada movies each year.[183] Bangalore also has a very active and vibrant theatre culture with popular theatres being Ravindra Kalakshetra[184] and the more recently opened Ranga Shankara[185] The city has a vibrant English and foreign language theatre scene with places like Ranga Shankara and Chowdiah Memorial Hall leading the way in hosting performances leading to the establishment of the Amateur film industry.[185] Kannada theatre is very popular in Bangalore, and consists mostly of political satire and light comedy. Plays are organised mostly by community organisations, but there are some amateur groups which stage plays in Kannada. Drama companies touring India under the auspices of the British Council and Max Müller Bhavan also stage performances in the city frequently.[186] The Alliance Française de Bangalore also hosts numerous plays through the year.

Bangalore is also a major centre of Indian classical music and dance.[187] The cultural scene is very diverse due to Bangalore's mixed ethnic groups, which is reflected in its music concerts, dance performances and plays. Performances of Carnatic (South Indian) and Hindustani (North Indian) classical music, and dance forms like Bharat Natyam, Kuchipudi, Kathakali, Kathak, and Odissi are very popular.[188] Yakshagana, a theatre art indigenous to coastal Karnataka is often played in town halls.[189] The two main music seasons in Bangalore are in April–May during the Ram Navami festival, and in September–October during the Dusshera festival, when music activities by cultural organisations are at their peak.[188] Though both classical and contemporary music are played in Bangalore, the dominant music genre in urban Bangalore is rock music. Bangalore has its own subgenre of music, "Bangalore Rock", which is an amalgamation of classic rock, hard rock and heavy metal, with a bit of jazz and blues in it.[190] Notable bands from Bangalore include Raghu Dixit Project, Kryptos, Inner Sanctum, Agam, All the fat children, and Swaratma.

The city hosted the Miss World 1996 beauty pageant.[191]

Education

Schools

Until the early 19th century, education in Bangalore was mainly run by religious leaders and restricted to students of that religion.[192] The western system of education was introduced during the rule of Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar. Subsequently, the British Wesleyan Mission established the first English school in 1832 known as Wesleyan Canarese School. The fathers of the Paris Foreign Missions established the St. Joseph's European School in 1858.[193] The Bangalore High School was started by the Mysore government in 1858 and the Bishop Cotton Boys' School was started in 1865. In 1945 when World War II came to an end, King George Royal Indian Military Colleges was started at Bangalore by King George VI; the school is popularly known as Bangalore Military School[194][195]

In post-independent India, schools for young children (16 months–5 years) are called nursery, kindergarten or play school which are broadly based on Montessori or multiple intelligence[196] methodology of education.[197] Primary, middle school and secondary education in Bangalore is offered by various schools which are affiliated to one of the government or government recognized private boards of education, such as the Secondary School Leaving Certificate (SSLC), Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), International Baccalaureate (IB), International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) and National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS).[198] Schools in Bangalore are either government run or are private (both aided and un-aided by the government).[199][200] Bangalore has a significant number of international schools due to expats and IT crowd.[201] After completing their secondary education, students either attend Pre University Course (PUC) or continue an equivalent high school course in one of three streams – arts, commerce or science with various combinations.[202] Alternatively, students may also enroll in diploma courses. Upon completing the required coursework, students enroll in general or professional degrees in universities through lateral entry.[203][204]

Below are some of the historical schools in Bangalore and their year of establishment.

- St John's High School [205](1854)

- United Mission School (1832)

- Goodwill's Girls School (1855)

- St. Joseph's Boys' High School (1858)

- Bishop Cotton Boys' School (1865)

- Bishop Cotton Girls' School (1865)

- Cathedral High School (1866)

- Baldwin Boys' High School (1880)

- Baldwin Girls' High School (1880)

- St. Joseph's Indian High School (1904)

- St Anthony's Boys' School (1913)

- Clarence High School (1914)

- National High School (1917)

- St. Germain High School (1944)

- Bangalore Military School (1946)

- Sophia High School (1949)

Universities

The Central College of Bangalore is the oldest college in the city, it was established in the year 1858. It was originally affiliated to University of Mysore and subsequently to Bangalore University. Later in the year 1882 the priests from the Paris Foreign Missions Society established the St Joseph's College, Bangalore. The Bangalore University was established in 1886, it provides affiliation to over 500 colleges, with a total student enrolment exceeding 300,000. The university has two campuses within Bangalore – Jnanabharathi and Central College.[206] University Visvesvaraya College of Engineering was established in the year 1917, by Sir M. Visvesvaraya, At present, the UVCE is the only engineering college under the Bangalore University. Bangalore also has many private engineering colleges affiliated to Visvesvaraya Technological University.

Some of the professional institutes in Bengaluru are:

- International Centre for Theoretical Sciences

- Indian Institute of Astrophysics

- Indian Institute of Science, which was established in 1909 in Bangalore

- Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR)

- National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS)

- National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS)

- Raman Research Institute

- National Law School of India University (NLSIU)

- Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore (IIM-B)

- Indian Statistical Institute

- Institute of Finance and International Management (IFIM)

- Institute of Wood Science and Technology

- International Institute of Information Technology, Bangalore (IIIT-B)

- National Institute of Design (NID),

- National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT),

- University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore (UASB)

- Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute (BMCRI)

- Sri Jayadeva Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences and Research (SJICR)

Some famous private institutions in Bangalore include Symbiosis International University, SVKM's NMIMS, CMR University, Christ University, Jain University, PES University, Dayananda Sagar University and M. S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences. Some famous private medical colleges include St. John's Medical College (SJMC), M. S. Ramaiah Medical College(MSRMC), Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences (KIMS), Vydehi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre (VIMS), etc.[207][208] The M. P. Birla Institute of Fundamental Research has a branch located in Bangalore.[209]

Media

The first printing press in Bangalore was established in 1840 in Kannada by the Wesleyan Christian Mission. In 1859, Bangalore Herald became the first English bi-weekly newspaper to be published in Bangalore and in 1860, Mysore Vrittanta Bodhini became the first Kannada newspaper to be circulated in Bangalore.[210][211]Vijaya Karnataka and The Times of India are the most widely circulated Kannada and English newspapers in Bangalore respectively, closely followed by the Prajavani and Deccan Herald both owned by the Printers (Mysore) Limited – the largest print media house in Karnataka.[212][213] Other circulated newspapers are Vijayvani, Vishwavani, Kannadaprabha, Sanjevani, Bangalore Mirror, Udayavani provide localised news updates. On the web, Explocity provides listings information in Bangalore.[214]

Bangalore got its first radio station when All India Radio, the official broadcaster for the Indian Government, started broadcasting from its Bangalore station on 2 November 1955.[215] The radio transmission was AM, until in 2001, Radio City became the first private channel in India to start transmitting FM radio from Bangalore.[216] In recent years, a number of FM channels have started broadcasting from Bangalore.[217] The city probably has India's oldest Amateur (Ham) Radio Club – Bangalore Amateur Radio Club (VU2ARC), which was established in 1959.[218][219]

Bangalore got its first look at television when Doordarshan established a relay centre here and started relaying programs from 1 November 1981. A production centre was established in the Doordarshan's Bangalore office in 1983, thereby allowing the introduction of a news program in Kannada on 19 November 1983.[220] Doordarshan also launched a Kannada satellite channel on 15 August 1991 which is now named DD Chandana.[220] The advent of private satellite channels in Bangalore started in September 1991 when Star TV started to broadcast its channels.[221] Though the number of satellite TV channels available for viewing in Bangalore has grown over the years,[222] the cable operators play a major role in the availability of these channels, which has led to occasional conflicts.[223] Direct To Home (DTH) services also became available in Bangalore from around 2007.[224]

The first Internet service provider in Bangalore was STPI, Bangalore which started offering internet services in early 1990s.[225] This Internet service was, however, restricted to corporates until VSNL started offering dial-up internet services to the general public at the end of 1995.[226] Bangalore has the largest number of broadband Internet connections in India.[227]

Namma Wifi is a free municipal wireless network in Bangalore, the first free WiFi in India. It began operation on 24 January 2014. Service is available at M.G. Road, Brigade Road, and other locations. The service is operated by D-VoiS and is paid for by the State Government.[228] Bangalore was the first city in India to have the 4th Generation Network (4G) for Mobile.[229]

Sports

Cricket and football are by far the most popular sports in the city. Bangalore has many parks and gardens that provide excellent pitches for impromptu games.[230] A significant number of national cricketers have come from Bangalore, including former captains Rahul Dravid and Anil Kumble. Some of the other notable players from the city who have represented India include Gundappa Vishwanath, Syed Kirmani, E. A. S. Prasanna, B. S. Chandrasekhar, Roger Binny, Venkatesh Prasad, Sunil Joshi, Robin Uthappa, Vinay Kumar, KL Rahul, Karun Nair, Brijesh Patel and Stuart Binny. Bangalore's international cricket stadium is the M. Chinnaswamy Stadium, which has a seating capacity of 55,000[231] and has hosted matches during the 1987 Cricket World Cup, 1996 Cricket World Cup and the 2011 Cricket World Cup. The Chinnaswamy Stadium is the home of India's National Cricket Academy.[232]

The Indian Premier League franchise Royal Challengers Bangalore and the Indian Super League club Bengaluru FC are based in the city. The city hosted some games of the 2014 Unity World Cup.

The city hosts the Women's Tennis Association (WTA) Bangalore Open tournament annually. Beginning September 2008, Bangalore has also been hosting the Kingfisher Airlines Tennis Open ATP tournament annually.[233]

The city is home to the Bangalore rugby football club (BRFC).[234] Bangalore has a number of elite clubs, like Century Club, The Bangalore Golf Club, the Bowring Institute and the exclusive Bangalore Club, which counts among its previous members Winston Churchill and the Maharaja of Mysore.[235] The Hindustan Aeronautics Limited SC is based in Bangalore.

India's Davis Cup team members, Mahesh Bhupathi[236] and Rohan Bopanna[237] reside in Bangalore. Other sports personalities from Bangalore include national swimming champion Nisha Millet, world snooker champion Pankaj Advani and former All England Open badminton champion Prakash Padukone.[238]

Bangalore is home to Bengaluru Beast,[239] 2017 vice champion of India's top professional basketball division, the UBA Pro Basketball League.

The city has hosted some games of the 2014 Unity World Cup.

Sister cities

See also

References

-

- Canton, Naomi (6 December 2012). "How the 'Silicon Valley of India' is bridging the digital divide". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- RAI, Saritha (20 March 2006). "Is the Next Silicon Valley Taking Root in Bangalore?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- Vaidyanathan, Rajini (5 November 2012). "Can the 'American Dream' be reversed in India?". BBC World News. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Basavaraja, Kadati Reddera (1984). History and Culture of Karnataka: Early Times to Unification. Chalukya Publications. p. 332. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- K. V. Aditya Bharadwaj (28 July 2015). "Bengaluru is growing fast, but governed like a village". The Hindu. Bengaluru. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Profile". Bangalore Metropolitan Region Development Authority. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- H.S. Sudhira; T.V. Ramachandra; M.H. Bala Subrahmanya (2007). "City Profile — Bangalore" (PDF). Cities. Bangalore. 24 (5): 382. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2007.04.003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- Bangalore Metropolitan/City Population section of "Bangalore Population Sex Ratio in Bangalore Literacy rate Bangalore". 2011 Census of India. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017.

- "The World's Cities in 2016" (PDF). United Nations. October 2016. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "INDIA STATS : Million plus cities in India as per Census 2011". Press Information Bureau, Mumbai. National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

-

- "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "Global city GDP rankings 2008–2025". PwC. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- "India's top 15 cities with the highest GDP Photos Yahoo! India Finance". Yahoo! Finance. 28 September 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "It is official: Bangalore becomes Bengaluru". The Times of India.

- "Karnataka (India): Districts, Cities, Towns and Outgrowth Wards – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts".

- Swaminathan, Jayashankar M. (2009). Indian Economic Superpower: Fiction Or Future?. Volume 2 of World Scientific series on 21st century business, ISSN 1793-5660. World Scientific. p. 20. ISBN 9789812814661.

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/1000-year-old-inscription-stone-bears-earliest-reference-to-Bengaluru/articleshow/17446311.cms

- Srinivas, S (22 February 2005). "The bean city". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- "India's 10 fastest growing cities". Rediff News. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 24 March 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- Broder, Jonathan (5 October 2018). "India Today". CQ Researcher. SAGE Publications. cqresrre2018100500. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- Chandramouli, K (25 July 2002). "The city of boiled beans". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- "Inscription reveals Bengaluru is over 1,000 years old". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 20 August 2004. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- Vijesh Kamath (30 October 2006). "Many miles to go from Bangalore to Bengalūru". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- Misra, Hemant; Jayaraman, Pavitra (22 May 2010). "Bangalore bhath: first city edifices". Mint. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- Aditi 2008, p. 6

- "Bangalore to be renamed Bengaluru". The Times of India. 11 December 2005. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- "It will be 'Bengaluru', resolves BMP". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 28 September 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- "It'll be 'Bengaluru' from November 1". Deccan Herald. 8 October 2006. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- "From today, Bangalore becomes Bengalooru". The Times of India. 1 November 2006. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- Renaming, Cities (18 October 2014). "Bangalore, Mysore, Other Karnataka Cities to be Renamed on 1 November" (ibtimes.co.in). ibtimes.co.in. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Renaming, Cities (18 October 2014). "Centre nod for Karnataka's proposal on renaming cities". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Bangalore dates from 4,000 BC". The Times of India. 11 October 2001. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Ranganna, T.S. (27 October 2001). "Bangalore had human habitation in 4000 B.C." The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Srinivas 2004, p. 69

- Edgar Thurston and K. Rangachari (1909). Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Government Press, Madras.

- Aditi 2008, p. 7

- Sarma (1992), p. 78

- Mysore: A Gazetteer Compiled for Government by B. L. Rice p.224

- "The Digital South Asia Library-Imperial gazetteer of India". uchicago.edu. 1908–1931. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2006.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Aditi 2008, p. 8

- Aditi 2008, p. 9

- Pinto & Srivastava 2008, p. 8

- Vagale, Uday Kumar (2004). "5: Bangalore: mud fort to sprawling metropolis" (PDF). Bangalore—future trends in public open space usage. Case study: Mahatma Gandhi Road, Bangalore (Thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. p. 34–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- Pinto & Srivastava 2008, p. 6

- Sandes, Lt Col E.W.C. (1933). The military engineer in India, vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-1-84734-071-9.

- "Raj Bhavan, Karnataka". The Homepage of Raj Bhavan, Government of Karnataka. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- Srinivas 2004, p. 3

- Ghosh, Jyotirmoy (2012). Entrepreneurship in tourism and allied activities: a study of Bangalore city in the post liberalization period (PDF). Pondicherry University. p. 86. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- Vagale, Uday Kumar (2004). "8: Public domain—contested spaces and lack of imageability" (PDF). Bangalore—future trends in public open space usage. Case study: Mahatma Gandhi Road, Bangalore (Thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. p. 49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- "1898 plague revisited". The Times of India. 17 November 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- Jaypal, Maya (26 March 2012). "Malleswaram, Basavanagudi, the new extensions". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- Karnataka State Gazetteer: Bangalore District, p. 91

- Srinivasaraju, Sugata (10 April 2006). "ElectriCity". Outlook India. Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- Pinto & Srivastava 2008, p. 10

- Mudur, Nirad; Hemanth CS (7 June 2013). "Bangalore torpedo gave them their D-Day, 69 years ago". Daily News and Analysis. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Nair 2005, p. 70

- S., Chandrasekhar (1985). Dimensions of Socio-Political Change in Mysore, 1918–40. APH Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8364-1471-4.

- Boland-Crewe, Tara; Lea, David (2004). The Territories and States of India. Psychology Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-203-40290-0.

When the new, extended Mysore was created on 1 November 1956 (by the addition of coastal, central and northern territories), Wodeyar became Governor of the whole state, which was renamed Karnataka in 1973.

- Srinivas 2004, p. 4

- "Death Toll Raised to 66 in Fire at Circus in India". The New York Times. 9 February 1981. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- Benjamin, Solomon (April 2000). "Governance, economic settings and poverty in Bangalore" (PDF). Environment & Urbanization. 12 (1): 35–36. doi:10.1177/095624780001200104. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- "Ground water information booklet" (PDF). Central Ground Water Board, Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India. December 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- "Finance budget for 2007–08" (PDF). Government of Karnataka. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- "District census handbook- Bangalore rural" (PDF). Directorate of census operations Karnataka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "Study area: Bangalore". Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- Tekur, Suma (11 March 2004). "Each drop of water counts". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- "Help/FAQ". Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board. Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- "Thirsty Bangalore invokes god". Hindustan Times. 9 June 2003. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- "Environmental impact analysis" (PDF). Bangalore Metropolitan Rapid Transport Corporation Limited, Government of Karnataka. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- Singh, Onkar (30 January 2000). "The Rediff interview. Dr S K Srivastav, additional director general, Indian Meteorological Department". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- "Rise in temperature 'unusual' for Bangalore". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 18 May 2005. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- "Bangalore". India Meteorological Department, Government of India. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2007.

- Bureau, Bengaluru (24 April 2016). "Bengaluru records highest temperature since 1931". The Hindu. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Amaresh, Vidyashree (10 May 2006). "Set up rain gauges in areas prone to flooding". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 16 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- Ashwini Y.S. (17 December 2006). "Bangalore weather back again". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- Bangalore. "Global monitoring precipitation". www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Sharma, Ravi (5 November 2005). "Bangalore's woes". The Frontline. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- "Station: Bangalore/Bangaluru Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 81–82. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M88. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Bangalore Climate Normals 1971–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- "Census population" (PDF). Census of India. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- "Provisional population totals, Census of India 2011" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- "Urban Agglomerations/Cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). Censusindia. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- "Cities having population 1 lakh and above" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "Kannadigas assured of all support". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 23 July 2004. Archived from the original on 30 June 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- "Population By Religious Community – Karnataka" (XLS). Office of The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015..Click on arrow adjacent to state Karnataka so that a Microsoft excel document is downloaded with district wise population of different religious groups. Scroll down to BBMP (M. Corp. + OG) in the document at row no. 596.

- "Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011" (PDF). Government of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- "Total Population, Slum Population ..." Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Census of India, 2001. 2006. Government of India

- Warah, Rasna. "Slums Are the Heartbeat of Cities" Archived 17 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine. The EastAfrican. 2006. National Media Group Ltd. 6 October 2003

- "Snaphhots – 2008" (PDF). National Crime Records Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- Roy, Ananya; Ong, Aihwa (2011). "Speculating on the Next World City". Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global. 42 (illustrated ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-4678-7.

- Kaminsky, Arnold P.; Long, Roger D. (2011). India Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic. 1 (reprint ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-313-37463-0.

- Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (2010). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World (revised ed.). Elsevier. p. 577. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4.

- Lindsay, Jennifer (2006). Between Tongues: Translation And/of/in Performance in Asia (illustrated, reprint, annotated ed.). NUS Press. p. 52. ISBN 9789971693398.

- Prashanth, G N. "A melting pot that welcomes all". The Times of India. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Sarma, Deepika (4 October 2012). "Building blocks of one of the city's largest communities". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Srinivas 2004, pp. 100–102, The Settlement of Tamil-Speaking Groups in Bangalore

- Srinivas 2004, p. 5

- Srivatsa, Sharath S. (31 October 2007). "Bangalore calling: it all goes way back..." The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- M. V. Chandrasekhar; Sahana Charan (23 December 2006). "They are now part of city's unique social mix". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Crossette, Barbara; Times, Special To the New York (20 January 1990). "Bangalore Journal; Christians Revel in Conversion Back to Indianness". The New York Times.

- Hefner, Robert W. (2013). Global Pentecostalism in the 21st Century. Indiana University Press. pp. 194–222. ISBN 978-0-253-01094-0.

- Christopher, Joseph (31 March 2014). "In the Indian rector's murder, the 'why' matters as much as the 'who'". UCA News. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- Gayer, Laurent; Jaffrelot, Christophe (2012). Muslims in Indian Cities: Trajectories of Marginalisation (illustrated ed.). Hurst Publishers. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-84904-176-8.

- 2011 census

- Prashanth, G. N. "How BMP became Bruhat". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Afshan Yasmeen (18 January 2007). "Greater Bangalore, but higher tax?". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "BBMP election result by 2 pm". Deccan Herald. India. 4 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "BJP wins Bangalore municipal elections for the first time". Daily News and Analysis. India. 5 April 2010. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- Reporter, Staff (28 September 2017). "Sampath Raj is city's new Mayor". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- "Gangambike elected as Bengaluru's new Mayor". The Economic Times. 28 September 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Ramachandra, T. V.; Pradeep P. Mujumdar. "Urban Floods: Case Study of Bangalore". Indian Institute of Science. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "Environmental Impact Analysis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2006. (362 KB). Bangalore Metropolitan Rapid Transport Corporation Limited. 2006. Government of Karnataka. 2005. (pp. 30–32)

- "The Bruhat Journey". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "Bangalore City Police" Archived 20 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Bangalore City Police. 2006. Karnataka State Police.

- "Constituency Wise Detailed Results" (PDF). Election Commission of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Rajendran, S. (19 April 2013). "Power of the city". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "About Us". Official webpage of BESCOM. Archived from the original on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- "BESCOM Mission Statement". Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "German consulate in Bangalore formally inaugurated". Deccan Herald. 21 November 2008. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "Nos coordonnées". Consulat général de France à Bangalore. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "Consulate of Japan, Bangalore". Embassy of Japan, New Delhi. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.