Snooker

Snooker (pronounced UK: /ˈsnuːkə/, US: /ˈsnʊkər/)[2][3] is a cue sport that originated among British Army officers stationed in India in the second half of the 19th century. It is played on a rectangular table covered with a green cloth (or "baize"), with pockets at each of the four corners and in the middle of each long side. Using a cue stick and 21 coloured balls, players must strike the white ball (or "cue ball") to pot or pocket the remaining balls in the correct sequence, accumulating points for each pot. An individual game (or frame) is won by the player scoring the most points. A match is won when a player wins a predetermined number of frames.

Three-time world champion Mark Selby playing a practice game | |

| Highest governing body | WPBSA IBSF |

|---|---|

| First played | 1875 in India |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Type | Cue sport |

| Equipment | Snooker table, snooker balls, cue, triangle, chalk |

| Venue | Snooker table |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | IOC recognition[1] |

| World Games | 2001 – present |

Snooker gained its identity in 1875 when army officer Sir Neville Chamberlain (1856–1944), stationed in Ooty (Ootacamund), Tamil Nadu, devised a set of rules that combined pyramid and black pool. The word snooker was a long-used military term for inexperienced or first-year personnel. The game grew in popularity in the United Kingdom, and the Billiards Association and Control Club was formed in 1919. It is now governed by the World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association (WPBSA).

The World Snooker Championship has taken place since 1927. Joe Davis, a key figure and pioneer in the early growth of the sport, won the championship 15 straight times between 1927 and 1946. The "modern era" began in 1969 after the broadcaster BBC commissioned the snooker television show Pot Black and later began to air the World Championship in 1978. Key figures in the game were Ray Reardon in the 1970s, Steve Davis in the 1980s, and Stephen Hendry in the 1990s, each winning six or more World championships. Since 2000, Ronnie O'Sullivan has won the most world titles, with six. Top professional players now compete regularly around the world and earn millions of pounds on the World Snooker Tour, which features players from across the world.

History

The origin of snooker dates back to the latter half of the 19th century.[4] In the 1870s, billiards was a popular activity among British Army officers stationed in Jabalpur, India, and several variations of the game were devised during this time.[4] One variation that originated at the officers' mess of the 11th Devonshire Regiment in 1875[5] combined the rules of two pocket billiards games: pyramid and black pool.[6][7] The former was played with fifteen red coloured balls positioned in a triangle, while the latter involved the potting of designated balls.[7][8] The game was developed in 1884 when its first set of rules was finalised by Sir Neville Chamberlain,[lower-alpha 1] an English army officer who helped develop and popularise the game at Stone House in Ooty on a table built by Burroughes & Watts that was brought over by boat.[9]

The word snooker was a slang term for first-year cadets and inexperienced military personnel, but Chamberlain would often use it for the performance of one of his fellow officers at the table.[4] In 1887, snooker was given its first definite reference in England in a copy of Sporting Life which caused a growth in popularity.[5] Chamberlain came out as the game's inventor in a letter to The Field published on 19 March 1938, 63 years after the fact.[5]

Snooker grew in popularity across the Indian colonies and the United Kingdom, but it remained a game mainly for the gentry, and many gentlemen's clubs that had a billiards table would not allow non-members inside to play.[5] To accommodate the growing interest, smaller and more open snooker-specific clubs were formed.[5] In 1919, the Billiards Association and the Billiards Control Board merged to form the Billiards Association and Control Club (BA&CC) and a new, standard set of rules for snooker first became official.[10]

In 1927 the first World Snooker Championship was organised by Joe Davis.[4][lower-alpha 2] Davis, as a professional English billiards and snooker player, moved the game from a pastime to a professional activity.[12] Davis won every world championship until 1946, when he retired from the championships.[13] The game went into a decline through the 1950s and 1960s with little interest generated outside of those who played.[14][7] In 1959, Davis introduced a variation of the game known as "Snooker Plus" to try to improve the game's popularity by adding two extra colours, but this failed to gain interest.[15][16] In 1969, David Attenborough commissioned the snooker television series Pot Black to demonstrate the potential of colour television, with the green table and multi-coloured balls being ideal for showing off the advantages of colour broadcasting.[7][17][18] The series became a ratings success and was for a time the second-most popular show on BBC2.[19] Interest in the game increased and the 1978 World Snooker Championship was the first to be fully televised.[20][21] The game quickly became a mainstream game in the United Kingdom,[22] Ireland and much of the Commonwealth, and has enjoyed much success since the late 1970s, with most of the ranking tournaments being televised.[7] By the 1985 World Snooker Championship a total of 18.5 million viewers watched the concluding frame of the final between Dennis Taylor and Steve Davis, a record viewership for the United Kingdom for any broadcast after midnight.[23][24] In the early 2000s, a ban on tobacco advertising led to a decrease in the number of professional tournaments,[25] with professional tournaments being cut to only 15 events in 2003, from 22 in 1999.[26][27] However, the popularity of the game in Asia, with emerging talents such as Liang Wenbo and more established players such as Ding Junhui and Marco Fu, boosted the sport in the Far East.[28][29] By 2007, the BBC dedicated 400 hours to snooker coverage, compared to just 14 minutes 40 years earlier.[30]

In 2010, promoter Barry Hearn gained a controlling interest in World Snooker Ltd. and the World Snooker Tour, pledging to revitalise the "moribund" professional game.[31][32][33] Since this time, the number of professional tournaments has increased, with 44 events in the 2019/20 season.[34] Events have also been made to be more suitable for television broadcasts, such as the Snooker Shoot-Out, a timed, one-frame tournament.[35] Prize money for professional events has also increased, with top players making several million pounds during their careers.[36] The winner of the 2020 World Snooker Championship will receive £500,000 out of a total fund of £2,395,000.[37]

Rules

Objective

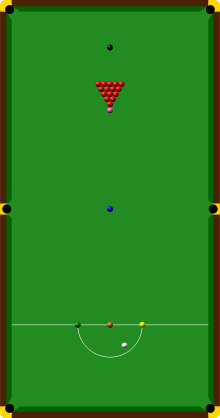

The objective of the game is to score more points than one's opponent by potting object balls in the correct order. At the start of a frame, the balls are positioned as shown in the first image, and the players then take turns hitting shots by striking the cue ball with the tip of the cue, their aim being to pot one of the red balls into a pocket and thereby score a point. Failure to make contact with the red ball constitutes a foul shot.[38] If the striker pots a red ball, he or she must then pot one of the six "colours".[lower-alpha 3] If the player successfully pots a colour, the value of that ball is added to the player's score, and the ball is returned to its starting position on the table. After that, the player must pot another red ball, then another colour, in sequence. This process continues until the striker fails to pot the desired ball, at which point the opponent comes to the table to play the next shot.[38] The act of scoring sequentially in this manner is to make a break (see scoring below).[38]

The game continues in this manner until all the reds are potted and only the six colours are left on the table.[38] At this point the colours must be potted in the order from least to most valuable ball, as per the table to the right. The shots are: yellow first (two points), then green (three points), brown (four points), blue (five points), pink (six points) and black (seven points), the balls not being returned to play.[38] When the final ball is potted, the player with more points wins.[38] If the scores are equal when all the balls have been potted, the black is placed back on its spot as a tiebreaker. In this situation, called re-spotted black, the black ball is placed on its designated spot and the cue ball is played as ball in hand. The referee then tosses a coin and the winner decides which player goes first. The frame continues until one of the players pots the black ball or commits a foul.[38] A player may also concede a frame while on strike if he or she thinks there are not enough points available on the table to beat the opponent's score. In professional snooker this is a common occurrence.[38][39] Professional and competitive amateur matches are officiated by a referee. The referee also replaces the colours on the table when necessary and calls out how many points the player has scored during a break.[40] Professional players usually play the game in a sporting manner, declaring fouls which they have committed but the referee has missed,[41] acknowledging good shots from their opponent, and holding up a hand to apologise for fortunate shots, known as "flukes".[41]

Scoring

Points in snooker are gained from potting the correct balls in sequence. The total number of consecutive points (excluding fouls) that a player amasses during one visit to the table is known as a break. A player attaining a break of 15, for example, could have reached it by potting a red then a black, then a red then a pink, before failing to pot the next red. A maximum break in snooker is achieved by potting all reds with blacks then all colours, yielding 147 points; this is often known as a "147" or just as a "maximum".[42]

| Colour | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Red | 1 point | |

| Yellow | 2 points | |

| Green | 3 points | |

| Brown | 4 points | |

| Blue | 5 points | |

| Pink | 6 points | |

| Black | 7 points | |

Points may also be scored in a game when a player's opponent fouls. A foul can occur for various reasons, most commonly for failing to hit the correct ball (e.g. hitting a colour first when the player was attempting to hit a red), or for sending the cue ball into a pocket. The former may occur when the player fails to escape from a "snooker" – a situation in which the previous player leaves the cue ball positioned such that no legal ball can be struck directly without obstruction by an illegal ball. Points gained from a foul vary from a minimum of four to a maximum of seven if the black ball is involved.[38]

A foul shot that leaves no valid shot for the opponent can leave them a free ball. A free ball allows a player to use any other coloured ball in place of the shot they were supposed to play. Doing so with all 15 red balls in play can result in a break exceeding a maximum, with the highest possible being a 155 break, achieved via the opponent leaving a free ball, with the black being potted as the additional colour, and then potting 15 reds and blacks with the colours.[38] Jamie Cope has the distinction of being the first player in snooker history to post a verified 155 break, achieved in a practice frame in 2005, with other players such as Alex Higgins also claiming to have made a similar break.[43][44]

One game, from the balls in their starting position until the last ball is potted, is called a "frame". A match generally consists of a predetermined number of frames and the player who wins the most frames wins the match. Most professional matches require a player to win five frames, and are called "best of nine" in reference to the maximum possible number of frames. Tournament finals are usually best of 17 or best of 19, while the world championship uses longer matches – ranging from best of 19 in the qualifiers and the first round up to best of 35 for the final (first to 18), and is played over four sessions of play held over two days.[45]

Governance and tournaments

The World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association (WPBSA, also known as World Snooker), founded in 1968 as the Professional Billiard Players' Association,[46] is the governing body for the professional competition.[47][48][49] The amateur game (including youth competition) is governed by the International Billiards and Snooker Federation (IBSF).[50] Events held specifically for women and events for seniors are handled by World Snooker under World Women's Snooker and the World Seniors Tour, respectively.[51][52][53] The highest levels of the sport are the IBSF World Snooker Championship, World Seniors Championship and the Ladies World Snooker Championship.[53]

Tournaments

Professional

Professional snooker players play on the World Snooker Tour. Events on the Tour are only open to players on the Tour and selected amateur players, but most events require qualification. Players can qualify for the Tour either by being high enough on the world rankings from prior seasons, winning continental championships, or through the Challenge Tour or Q School events.[54] Players on the Tour generally gain two-year participation for the events.[54]

Reflecting the game's aristocratic origins, the majority of tournaments on the professional circuit require players to wear waistcoats and bow ties. In recent years the necessity for this has been questioned, and players such as Stephen Maguire have been granted medical exemptions from wearing a bow tie.[55]

The Tour also has an official world rankings scheme, with only players on the Tour receiving a ranking. Ranking points, earned by players through their performances over the previous two seasons, determine the current world rankings.[56] A player's ranking determines what level of qualification he or she requires for specific tournaments. The elite of professional snooker are generally regarded as the "top-16" ranking players.[57] They are not required to pre-qualify for some of the tournaments, such as the Shanghai Masters, the Masters and the World Snooker Championship.[58] Certain other events, such as those in the Coral Cup series, use the one-year ranking list to qualify; these use the results of the current season to denote participants.[59] Currently, the Tour contains 125 players, with players either in the top 64 on the official ranking list, or finishing as one of the top eight prize money earners during the most recent season, guaranteed a tour place for the next season, this being assessed after the World Championship.[60]

The oldest professional snooker tournament is the World Championship,[45] held annually since 1927 (except during World War II and between 1958 and 1963).[61][62] The tournament has been held at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, England, since 1977, and was sponsored by Embassy from 1976 to 2005.[25] Since the ban on advertising tobacco products, the championships have been sponsored by betting companies.[63][64][65]

The World Championship is the most highly valued prize in professional snooker[66] in terms of financial reward (£500,000 for the winner, formerly £300,000), ranking points and prestige.[67][68] It is televised extensively in the UK by the BBC[69] and gains significant coverage in Europe on Eurosport[70] and in East Asia on CCTV-5.[71] The World Championships is part of the Triple Crown along with the UK Championship and the non-ranking Masters.[72] These events are valued by some players as the most prestigious, and are also some of the oldest competitions. Winning all three events is a difficult task, and has only been done by 11 players.[73][57][72]

With some events having been criticised for matches taking too long,[74] an alternative series of timed tournaments has been organised by Matchroom Sport chairman Barry Hearn. The shot-timed Premier League Snooker was established, with seven players invited to compete at regular United Kingdom venues, televised on Sky Sports.[68] Players had twenty-five seconds to take each shot, with five time-outs per player per match. While some success was achieved with this format, it generally did not receive the same amount of press attention or status as the regular ranking tournaments.[74] This event has been taken out of the tour since 2013, when the Champion of Champions was established.[75] The Champion of Champions saw players qualify by virtue of winning other events in the season, with 16 champions competing.[76][lower-alpha 4]

In 2015, the World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association submitted an unsuccessful bid for snooker to be played at the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.[1][77] Another bid has been put forward for 2024 Summer Olympics through the World Snooker Federation, founded in 2017.[78][79] A trial for the format for cue sports to be played at the 2024 games was put forward at the 2019 World Team Trophy, also featuring nine-ball and carom billiards.[80] Snooker has been contested at the World Games since 2001, and was included as an event at the 2019 African Games.[81][82][83]

Criticisms

Several players, such as Ronnie O'Sullivan, Mark Allen and Steve Davis, have warned that there are too many tournaments during the season, and that players risk burning out.[84] In 2012, O'Sullivan played fewer tournaments in order to spend more time with his children, and ended the 2012–13 season ranked 19th in the world.[84] Furthermore, he did not play any tournament in 2013 except the World Championship, which he won.[84] O'Sullivan has suggested that a "breakaway tour" with fewer events would be beneficial to the sport, but as of 2019 no such tour has been organised.[85]

Some leagues have allowed clubs to refuse to accept women players in tournaments.[86][87] League committee leadership defended the practice, saying, "If we lose two of these clubs [with the men-only policies] we would lose four teams and we can't afford to lose four teams otherwise we would have no league."[86] A World Women's Snooker spokesperson said, "It is disappointing and unacceptable that in 2019 that players such as Rebecca Kenna have been the victim of antiquated discriminatory practices."[88] The All-Party Parliamentary Group said, "The group believes that being prevented from playing in a club because of gender is archaic."[88]

Equipment

and two cue sticks

Accessories used for snooker include chalk for the tip of the cue, rests of various sorts used for playing shots that cannot be played by hand, a triangle to rack the reds, and a scoreboard. One drawback of snooker on a full-size (12 ft × 6 ft [366 cm × 183 cm]) table is the size of the room (22 by 16 feet [6.7 m × 4.9 m]), which is the minimum required for comfortable cueing room on all sides.[89] This limits the number of locations in which the game can easily be played. While pool tables are common to many pubs, snooker tends to be played either in private surroundings or in public snooker halls. The game can also be played on smaller tables using fewer red balls. Variant table sizes include 10 ft × 5 ft (305 cm × 152 cm), 9 ft × 4.5 ft (274 cm × 137 cm), 8 ft × 4 ft (244 cm × 122 cm), 6 ft × 3 ft (183 cm × 91 cm) (the smallest for realistic play) and 4 ft × 2 ft (122 cm × 61 cm). Smaller tables can come in a variety of styles, such as fold-away or dining-table convertible.[90]

A traditional snooker scoreboard resembles an abacus and records the score for each frame in units and twenties and the frame scores. They are typically attached to a wall by the snooker table. A simple scoring bead is also sometimes used, called a "scoring string", or "scoring wire".[40] Each bead (segment of the string) represents a single point. Snooker players typically move one or several beads with their cue.[40]

The playing surface is 356.9 cm (11 feet 8.5 inches) by 177.8 cm (5 feet 10 inches) for a standard full-size table, with six pocket holes, one at each corner and one at the centre of each of the longer side cushions.[91]

The felt is usually a form of fully wool green baize, with a directional nap running from the baulk end of the table towards the end with the black ball spot. The nap will affect the direction of the cue ball depending on which direction the cue ball is shot and also on whether left or right side (spin) is placed on the ball. Even if the cue ball is hit in exactly the same way, the nap will cause a different effect depending on whether the ball is hit down table (towards the black ball spot) or up table (towards the baulk line). The cloth on a snooker table is not vacuumed, as this can destroy the nap. The cloth is brushed in a straight line from the baulk end to the far end with multiple brush strokes that are straight in direction (i.e. not across the table). Some table men will also then drag a dampened cloth wrapped around a short piece of board (like a two by four), or straight back of a brush to collect any remaining fine dust and help lay the nap down. The table is then ironed. Strachan cloth, used in official snooker tournaments, is 100% wool. Some other cloths include a small percentage of nylon.[92][93]

Important players

In the professional era that began with Joe Davis in the 1930s and continues until the present day, a relatively small number of players have succeeded at the top level.[94][95] Joe Davis was world champion for twenty years, retiring unbeaten after claiming his fifteenth world title in 1946 when the tournament was reinstated after the Second World War.[96] Davis was unbeaten in World Championship play, and was only ever beaten four times in his entire life, with all four defeats coming after his World Championship retirement and inflicted by his own brother Fred Davis.[96] He did lose matches in handicapped tournaments, but on level terms these four defeats were the only losses of his entire career.[97] He was also world billiards champion.[96][98] It is regarded as highly unlikely that anyone will ever dominate the game to this level again.[99]

After Davis retired from World Championship play, the next dominant force was his younger brother Fred Davis, who had lost the 1940 final to Joe.[96] By 1947, Fred Davis was deemed ready by his brother to take over the mantle, but lost the world final to the Scotsman Walter Donaldson.[100] Davis and Donaldson would contest the next four finals. After the abandonment of the World Championship in 1953, with the 1952 final boycotted by British professionals, the World Professional Match-play Championship became the unofficial world championship.[101] Fred Davis won the event every year until its penultimate one, in 1957, which he did not enter.[102]

_2012-02-05_05_cropped.jpg)

John Pulman was the most successful player of the 1960s, when the world championship was contested on a challenge basis.[103] However, when the tournament reverted to a knockout formula in 1969, he did not prosper. Ray Reardon became the dominant force in the 1970s, winning six titles (1970, 1973–1976 and 1978), with John Spencer winning three.[104][105]

Steve Davis' first world title in 1981 made him only the 11th world champion since 1927, including the winner of the boycotted 1952 title, Horace Lindrum.[106][107] Davis would win six World Championships (1981, 1983, 1984 and 1987–1989), and competed in the most watched snooker match ever, the 1985 World Snooker Championship final with Dennis Taylor.[23] Stephen Hendry became the 14th in 1990 and dominated through the 1990s, winning seven titles (1990, 1992–1996 and 1999).[102][108] Ronnie O'Sullivan is the closest to dominance in the modern era, having won the title on six occasions in the 21st century (2001, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2013, and 2020).[102] Mark Williams has won three times (2000, 2003 and 2018) and John Higgins four times (1998, 2007, 2009 and 2011), but since the beginning of the century, there has not been a dominant force like in previous decades, and the modern era has seen many players playing to a similar standard, instead of one player raising the bar. Davis, for example, won more ranking tournaments than the rest of the top 64 players put together by 1985. By retaining his title in 2013, O'Sullivan became the first player to successfully defend the World Championship since Hendry in 1996 (Mark Selby would also do this in 2017).[109]

Variants

- American snooker, a variant dating to 1925, usually played on a 10 ft × 5 ft (3.0 m × 1.5 m) table with 2 1⁄8 in (54 mm) balls, with a simpler rule set influenced by pool. (Despite its name, the strictly amateur American snooker is not governed or recognised by the United States Snooker Association, but by the Billiard Congress of America.)[110]

- Power Snooker, a variant with only nine reds in a diamond-shaped pack, instead of 15 in a triangle, and matches limited to 30 minutes.[111]

- Sinuca brasileira, a Brazilian version with only one red ball, and divergent rules.[112]

- Six-red snooker, a variant played with only six reds in a triangular pack.

- Snookerpool, a variant played on an American pool table with ten reds in a triangular pack.

- Snookerpool Rapide, a variant of Snookerpool, but with a 15-second shot clock.

- Snooker plus, a variant with two additional colour balls (8pt orange and 10pt purple), allowing a maximum break of 210.[113][114] The variation was created by Joe Davis in 1959 and used at the 1959 News of the World Snooker Plus Tournament. It failed to gain popularity.

- Tenball, a snooker variant specifically for the television show of the same name. A yellow and black ball placed between the blue and pink worth ten points is added. The game had slightly revised rules, and lasted for one series presented by Philip Schofield.

Notes

- not the Prime Minister of the same name

- The event was known then as the Professional Snooker Championship.[11]

- In snooker, the term colour is understood to exclude the red balls.[38]

- Under certain circumstances, some runners-up participate at the event.[76]

References

- "Snooker bids to be included in 2020 Olympics in Tokyo". BBC Sport. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Pronunciation of snooker". Macmillan Dictionary. London, UK: Macmillan Publishers. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- "American pronunciation of snooker". Macmillan Dictionary. op. cit. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- Maume, Chris (26 April 1999). "Sporting Vernacular 11. Snooker". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Clare, Peter (2008). "Origins of Snooker". Snooker Heritage. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Moreman, T. R. (25 May 2006). "Chamberlain, Sir Neville Francis Fitzgerald (1856–1944), army officer and inventor of snooker". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73766.

- "Full History of Snooker - WPBSA". WPBSA. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Shamos, Michael I. (1994). Pool: History, Strategies, and Legends. New York City: Friedman Fairfax. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-56799-061-4.

- Hughes-Games, Martin (16 June 2014). "Ooty, India: back in time to the birthplace of snooker". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Gadsby & Williams 2012, p. 8.

- "Professional snooker". Dundee Courier. 13 November 1926. Retrieved 21 January 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Smith, John A. "Cues n Views - History Page, timeline". cuesnviews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 February 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

Joe Davis will reinvent this after-dinner pastime and become world champion

- "Billiards and Snooker – J Davis retires". The Times. 7 October 1946. p. 8.

- "Snooker win to Pulman". The Sydney Morning Herald. 11 March 1968. p. 12. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Snooker Plus". The Glasgow Herald. 27 October 1959. p. 10. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- "J Davis launches Snooker Plus". The Times. 27 October 1959. p. 17.

- "Pot Black returns". BBC Sport. 27 October 2005. Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "2008 Summer Journey - TIME". TIME.com. 19 June 2008. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Callan, Frank (15 March 2007). "Pot Black Ratings". FCSnooker.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

Surprisingly, the programme raced to second place in the BBC2 ratings

- "Take snooker to the world". BBC Sport. 5 May 2002. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "1978 – The World Snooker Championships". 27 April 2006. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

By 1977, though, a new lighting system had been devised, allowing the players to be seen clearly without problems and, the following year, Aubrey Singer agreed to cover the World Championships all the way through, with an hour of highlights every day for 16 days

) - MacInnes, Paul (10 February 2004). "Thatch of the day". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "1985: The black ball final". BBC Sport. 18 April 2003. Archived from the original on 24 September 2003. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

Dennis Taylor's remarkable 18-17 victory over Steve Davis on the final black has justifiably become regarded as one of the great moments in British sport.

- "Great Sporting Moments: Dennis Taylor defeats Steve Davis 18–17 at the Crucible". The Independent. 12 July 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Anstead, Mike (19 January 2006). "Snooker finds sponsor with deep pockets". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "WWW Snooker: Tournament Diary 1998/99". snooker.org. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "WWW Snooker: The 2003/2004 Season". snooker.org. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Chowdhury, Saj (22 January 2007). "China in Ding's hands". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 27 August 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Harlow, Phil (4 April 2005). "Could Ding be snooker's saviour?". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "John Spencer, 71, Dies; Helped Popularize Snooker". The New York Times. 16 July 2006. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "Barry Hearn wins vote to take control of World Snooker". BBC Sport. 2 June 2010. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Phillips, Owen (27 November 2013). "Barry Hearn: World Snooker chief on 'how he saved the sport'". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Barry Hearn wins vote to take control of World Snooker". The Guardian. Press Association. 2 June 2010. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Calendar 2019/2020 - snooker.org". snooker.org (in Norwegian). Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "2019 BetVictor Shoot Out - World Snooker". World Snooker. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "World Snooker prize money increase highlights growth, says Barry Hearn". BBC Sport. 8 July 2019. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "2019–2020 Season Summary" (PDF). worldsnooker.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Official Rules of the Games of Snooker and English Billiards" (PDF). The World Professional Billiards & Snooker Association Limited. November 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Snooker for beginners". Snooker rules and refereeing. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "What is Scoreboard in Snooker? Definition and Meaning". sportsdefinitions.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "Mark Allen pockets £70k Scottish Open title with a 'nice fluke' - BelfastTelegraph.co.uk". BelfastTelegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Ding compiles maximum at Masters". BBC Sport. 14 January 2007. Archived from the original on 7 February 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Alex Higgins: A 155 break impossible? Not for Higgy - BelfastTelegraph.co.uk". BelfastTelegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "147 Is Not Snooker's Maximum Break". Pundit Arena. 2 December 2014. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Chowdhury, Saj (2 May 2006). "World title victory delights Dott". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "WPBSA v TSN". BBC Sport. 16 February 2001. Archived from the original on 1 January 2003. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Snooker's biggest break". BBC Sport. 7 December 2000. Archived from the original on 17 December 2003. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Snooker authorities survive bid". BBC Sport. 13 November 2002. Archived from the original on 26 May 2004. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Everton, Clive (14 November 2002). "Snooker at the crossroads". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 11 July 2004. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "About Us". IBSF.info. International Billiards and Snooker Federation. 2017. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "Women's Billiards. Association Formed to Control the Championships". Lancashire Evening Post. p.10. 1 October 1931 – via The British Newspaper Archive. Retrieved 21 August 2019.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "No interference". Gloucestershire Echo. p.5. 30 November 1933 – via The British Newspaper Archive. Retrieved 21 August 2019.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "WPBSA World Seniors Tour - World Snooker". World Snooker. 3 May 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Main Tour Qualification 2019/20 - WPBSA". WPBSA. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Mason, Mark (20 April 2017). "It's finally time snooker ditched the bow tie". The Spectator.

- "Professional Tour ranking points" (PDF). World Snooker. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- "Swail targeting place in top 16". BBC Sport. 1 August 2006. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Everton, Clive (24 November 2000). "The Seeds of Success". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 18 October 2003. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- "Coral Cup: World Grand Prix first on the agenda for new competition". Coral News. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Tour Survival 2019: Five to Go". wpbsa.com. World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "History of the World Snooker Championship". worldsnooker.com. World Professional Billiards and Snooker Association. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- "Embassy World Championship". Snooker Scene. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Huge financial blow hits snooker". BBC Sport. 6 August 2008. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- "Crucible event gets new sponsor". BBC Sport. 15 January 2006. Archived from the original on 13 February 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- "World Snooker Announcements: Betfred.com Named Title Sponsor for the World Snooker Championship". Archived from the original on 19 June 2012.

- "Doherty sets out to regain greatest prize". The Independent. 20 April 2001. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2007 – via FindArticles.

- "World's best ready for Crucible". BBC Sport. 13 April 2006. Archived from the original on 24 April 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Chowdhury, Saj (21 February 2005). "Where does Ronnie rank?". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 1 June 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Snooker signs five-year BBC deal". BBC Sport. 26 October 2005. Archived from the original on 23 February 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Day, Julia (27 April 2006). "Eurosport pots TV snooker rights". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- "Tournament Broadcasters 2019-20 - World Snooker". World Snooker. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Harris, Nick (15 January 2007). "An email conversation with Graeme Dott: 'We need an Abramovich to take the game to a new level". The Independent. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Hayton, Eric; Dee, John (2004). The CueSport Book of Professional Snooker: The Complete Record & History. London: Rose Villa Publications. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-9548549-0-4.

- Ronay, Barney (27 October 2006). "Too dull to miss". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- "O'Sullivan excited by new Champion of Champions event". ESPN.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Champion of Champions Qualifying Criteria Confirmed - Champion of Champions Snooker". Champion of Champions Snooker. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Olympic Games: Snooker misses out on 2020 Tokyo place". BBC Sport. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Reuters staff (8 November 2017). "Snooker among cue sports targeting Paris 2024, federation chief says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "About". worldsnookerfederation. World Snooker Federation. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Inaugural World Team Trophy Sees 24 of the Best Cuesports Champions Assemble in Paris". azbilliards.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Billiards/Snooker/Men/". World Games 2001 Akita. Archived from the original on 19 March 2002. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- "Snooker Results (Men)". Sports123.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Pavitt, Michael (11 January 2019). "Snooker to feature as medal event at 2019 African Games in Morocco". Inside the Games. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Goulding, Neil (7 May 2012). "Snooker: Ronnie O'Sullivan warns of players burning out". The Independent. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020.

- Hafez, Shamoon (2 December 2018). "Ronnie O'Sullivan 'ready to go' with breakaway snooker tour". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Snooker player quits over 'men-only' rule". 26 March 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Horsburgh, Lynette (29 March 2019). "'You're a girl, you can't play snooker at the Crucible'". Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "MPs call for end to men-only snooker clubs". 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Peter Ietswaart, Ietswaart, Peter. "Thurston Snooker Table makers". Archived from the original on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

Recommended room size for full size table 22 ft × 16 ft

- "Pool Table Room Size Guide - Snooker & Pool Table Company Ltd". snookerandpooltablecompany.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- "Cuesport equipment". ActiveSG. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Milliken Industrials Limited - Woollen Speciality Products. "Strachan snooker cloths - WSP Textiles - Billiard and Tennis cloths". Archived from the original on 9 February 2016.

- "Tournament Grade 9ft Pool Snooker Cloth Set - Choose Your Colour". Cues Cues. 10 July 2013. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Everton, Clive (10 May 2002). "O'Sullivan in exalted company". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 27 August 2003. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Hunter, Paul (5 November 2004). "Putting in the practice". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Turner, Chris. "Player Profile – Joe Davis OBE". Chris Turner's Snooker Archive. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Davis, Fred (1979). Talking Snooker. London: A and C Black. ISBN 978-0-7136-1991-1.

- Gadsby, Paul; Williams, Luke (2012). Snooker's World Champions: Masters of the Baize. Random House. ISBN 978-1-780-57715-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Everton, Clive (1986). The History of Snooker and Billiards. Haywards Heath: Partridge Press. ISBN 978-1-85225-013-3.

- "Davis just misses world record". Western Daily Press. 22 October 1947. Retrieved 18 March 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Everton, Clive (1982). Guinness Book of Snooker. Guinness World Records Limited. ISBN 978-0-85112-256-4.

- Turner, Chris. "World Professional Championship". cajt.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk. Chris Turner's Snooker Archive. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- "World Championship 1964". Global Snooker. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Nunns, Hector (8 April 2014). "Before the Crucible". Inside Snooker. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- "Snooker – Reardon's a class above rest". The Times. 24 April 1976. p. 15.

- "Champion at 23". The Times. 21 April 1981. p. 1.

- "Snooker – Davis can beat the system". The Times. 7 April 1981. p. 10.

- "World Championship – Roll of Honour". Global Snooker. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "World Snooker Championship – History". World Snooker. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "Rules Governing the Royal Game of Billiards". Chicago: Brunswick–Balke–Collender. 1925. pp. 40–48.

- Goodley, Simon (24 October 2010). "Power Snooker launch will be at O2 arena". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- 2013, Mike Stooke. "The rules of Brazilian Snooker (Sinuca Brasileira)". snookergames.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Definitions of terms used in Snooker and English Billiards (search for snooker plus)". snookergames.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- "Snooker Plus". The Glasgow Herald. 27 October 1959. p. 10. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Look up snooker in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |