The Battle of the Somme (film)

The Battle of the Somme (US title, Kitchener's Great Army in the Battle of the Somme), is a 1916 British documentary and propaganda war film, shot by two official cinematographers, Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell. The film depicts the British Army in the preliminaries and early days of the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916). The film premièred in London on 10 August 1916 and was released generally on 21 August. The film depicts trench warfare, marching infantry, artillery firing on German positions, British troops waiting to attack on 1 July, treatment of wounded British and German soldiers, British and German dead and captured German equipment and positions. A scene during which British troops crouch in a ditch then "go over the top" was staged for the camera behind the lines.

| The Battle of the Somme | |

|---|---|

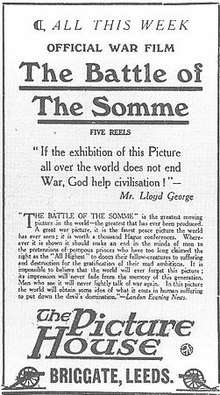

Yorkshire Evening Post advert for the film, 1916 | |

| Produced by | W. F. Jury |

| Music by | J. Morton Hutcheson (original 1916 medley) Laura Rossi (2006) |

| Cinematography | G. H. Malins J. B. McDowell |

| Edited by | Charles Urban G. H. Malins |

| Distributed by | British Topical Committee for War Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 74 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | Silent film English intertitles |

The film was a great success, watched by about 20 million people in Britain in the first six weeks of exhibition and distributed in eighteen other countries. A second film, covering a later phase of the battle, was released in 1917 as The Battle of the Ancre and the Advance of the Tanks. In 1920 the film was preserved in the film archive of the Imperial War Museum. In 2005 it was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register and digitally restored, and in 2008, was released on DVD. The Battle of the Somme is significant as an early example of film propaganda, an historical record of the battle and as a popular source of footage illustrating the First World War.

Film

Content

The Battle of the Somme is a black-and-white silent film in five parts, with sequences divided by intertitles summarising the contents. The first part shows preparations for battle behind the British front line; there are sequences of troops marching towards the front, French peasants continuing their farm work in rear areas, the stockpiling of munitions, Major-General Beauvoir De Lisle addresses the 29th Division and some of the preparatory bombardment by 18-pounder, 60-pounder and 4.7-inch guns, 6-inch, 9.2-inch howitzers and 2-inch mortars is shown. The second part depicts more preparations, troops moving into front line trenches, the intensification of the artillery barrage by 12-inch and 15-inch howitzers, a 9.45-inch Heavy Mortar and the detonation of the mine under the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt. Part three begins with the attack on First day on the Somme (1 July 1916), with some re-enactments and shows the recovery of British wounded and German prisoners. The fourth part shows more scenes of British and German wounded, the clearing of the battlefield and some of the aftermath. The final part shows scenes of devastation, including the ruins of the village of Mametz, British troops at rest and preparations for the next stage of the advance.[1]

Production

Background

_1.jpg)

On 2 November 1915, the British Topical Committee for War Films, representing British newsreel producers and supported by the War Office, despatched two cameramen to France. Geoffrey Malins of Gaumont British and Edward Tong of Jury's Imperial Pictures, were to shoot footage for short newsreels.[3] By early June Tong had fallen ill and been sent home but he and Malins had made five series of newsreels, which although well-received, had failed to impress the British cinema trade.[3] John McDowell, of the British & Colonial film company, volunteered to replace Tong and left for France on 23 June 1916.[3] On 24 June, the British Army began the preparatory artillery bombardment of German positions for the Battle of the Somme.[4]

Photography

Malins and McDowell shot the film between 26 June and 7–9 July. Malins filmed in the vicinity of Beaumont Hamel, on attachment with the 29th Division (VIII Corps); McDowell worked further south near Fricourt and Mametz with the 7th Division (XV Corps).[5]

Before the battle, Malins worked at the north end of the British Somme sector, photographing troops on the march and heavy artillery west of Gommecourt. De Lisle suggested to Malins that he view the bombardment of Beaumont Hamel from Jacob's Ladder near White City, an abrupt drop down the side of a valley, with about 25 steps cut into the ground, showing up white because of the chalk.[6] Sappers had dug the large mine under Hawthorn Ridge in front of White City near Beaumont Hamel. German shells were falling as Malins made his way to Lanwick Street Trench. Malins had to rise above the parapet to remove sandbags and then set up his camera, which was camouflaged with sackcloth. Malins returned to film the speech by de Lisle to the 2nd Royal Fusiliers, after which Malins heard of the postponement of the battle for 48-hours. Malins returned to White City to film the bombardment of the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt by trench mortars, during which there were three misfires, which destroyed a trench-mortar position nearby.[7]

On 1 July Malins filmed troops of the 1st Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers waiting to advance at Beaumont Hamel from a sunken lane in no man's land, which had been occupied by digging a 2 ft × 5 ft (0.61 m × 1.52 m) tunnel overnight. Malins then went back to Jacob's ladder to film the explosion of the Hawthorn Ridge mine. At 7:19 a.m. Malins began filming and the mine detonation shook the ground as troops of Royal Engineers advanced on either side to occupy the crater. Later in the day a shell explosion damaged the camera tripod; Malins repaired the tripod and in the evening filmed roll-calls.[8] Next day Malins shot film at La Boisselle before leaving for London around 9 July.[9] Malins returned to France, and from 12–19 July filmed sequences of shellfire and of troops advancing from trenches, which were staged for the camera at a Third Army mortar school near St Pol.[9]

McDowell reached the Somme front after Malins and began filming British preparations on 28 or 29 June, to the east of Albert. He covered the opening day of the battle from the vicinity of Carnoy and from the dressing-station at Minden Post. The success of the 7th Division enabled McDowell to film captured German trenches near Fricourt and Mametz.[9]

Editing

On 10 July, Brigadier-General John Charteris reported to the War Office that some 8,000 feet (2,400 m) of footage had been shot and recommended that sections of film should be released as soon as possible. Footage was first viewed as a negative on 12 July and Charles Urban is thought to have begun work on the film as editor, with the assistance of Malins.[10] Urban later claimed to have proposed that the film be issued as a feature film rather than in short sections. The change in format was agreed with the British Topical Committee for War Films and a 5,000 feet (1,500 m) cut of the film was ready by 19 July.[10] Much footage was censored from the public version, as the War Office wanted the film to contain images that would support the war effort and raise morale.[5] A 77-minute version was ready by 31 July and a rough cut was screened at the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) General Headquarters (GHQ) at Montreuil, Pas-de-Calais and at the Fourth Army headquarters. The commander Lieutenant-General Henry Rawlinson said "some of it is very good but it cut out many of the horrors in dead and wounded".[11][12] The film was shown to the Secretary of State for War, David Lloyd George on 2 August and members of the cinema trade late on 7 August, the day that the film received final approval for release.[12]

Release

The film comprises five reels and is 77 minutes long.[13] The first screening took place on 10 August 1916 at the Scala Theatre, to an audience of journalists, Foreign Office officials, cinema trade figures and officers of the Imperial General Staff. The screening was preceded by the reading of a letter from Lloyd George, exhorting the audience to "see that this picture, which is in itself an epic of self-sacrifice and gallantry, reaches everyone. Herald the deeds of our brave men to the ends of the earth. This is your duty."[14]

A musical medley with excerpts from classical, folk, contemporary and popular pieces, to be played live in cinemas by accompanying musicians, was devised by J. Morton Hutcheson and published in The Bioscope on 17 August 1916.[15] On 21 August, the film began showing simultaneously in thirty-four London cinemas and opened in provincial cities the following week, when the film was shown simultaneously at twenty cinemas in Birmingham, at least twelve cinemas in Glasgow and Edinburgh, six cinemas in Cardiff and three in Leeds.[12][16][17] The Royal Family received a private screening at Windsor Castle on 2 September; the film was eventually shown in more than eighteen countries.[18]

Reception

Britain

The popularity of the film was unprecedented and cinemas played the film for longer runs than usual, often to packed houses, while some arranged additional screenings to meet demand.[20] The film is thought to have achieved attendance figures of twenty million in its first six weeks of release.[21] The film also attracted more middle-class audiences, some of whom had never been to a cinema before.[20] William Jury, as the film's booking director, initially charged exhibitors £40, with the fee decreasing by £5 a week; after two months, a reduced fee of £6 for three nights put the film within the price range of village halls wishing to show the film.[16] By October 1916, the film had been booked by more than two thousand cinemas in Britain, earning over £30,000.[22] British authorities showed the film to the public as a morale-booster and in general it met with a favourable reception. The Times reported on 22 August that

Crowded audiences ... were interested and thrilled to have the realities of war brought so vividly before them, and if women had sometimes to shut their eyes to escape for a moment from the tragedy of the toll of battle which the film presents, opinion seems to be general that it was wise that the people at home should have this glimpse of what our soldiers are doing and daring and suffering in Picardy.

— The Times, 22 August 1916[23]

Some members of the audience considered it immoral to portray scenes of violence; Hensley Henson, the Dean of Durham, protested "against an entertainment which wounds the heart and violates the very sanctity of bereavement". Others complained that such a serious film shared the cinema programme with comedy films.[24] On 28 August, the Yorkshire Evening Post printed the comment, attributed to Lloyd George, "If the exhibition of this Picture all over the world does not end War, God help civilisation".[25] The film was shown to British troops in France from 5 September; Lieutenant-Colonel Rowland Feilding, an officer who saw the film in a muddy field near Morlancourt, described it as "a wonderful and most realistic production" but criticised the film for failing to record the sound of rifles and machine-guns, although there was an artillery accompaniment from guns firing nearby.[5] Feilding suggested that the film could reassure new recruits, by giving them some idea of what to expect in battle; the intertitles were forthright, describing images of injury and death.[26]

International

The film was shown in New Zealand in October 1916. On 12 October, the Wellington Evening Post ran an advertisement for the film, describing it as "the extraordinary films of 'the big push' and "an awe-inspiring, glorious presentation of what our heroes are accomplishing today".[27] In a review published on 16 October, it was written that "these pictures of the Battle of the Somme are a real and valuable contribution to the nation's knowledge and a powerful spur to national effort".[28] The film premièred in Australia on 13 October at Hoyt's Picture Theatre in Melbourne. The Melbourne Argus considered that after the attack sequence, "... you are not in a Melbourne picture theatre, but in the very forefront of the Somme battle" and called the film "this moving reality of battle".[29]

The film and its reception was of great interest to Germans, who were able to read a report from a neutral reporter in London, filed in the Berliner Tageblatt. British cinema was said to be taking a serious view of the war, helped by the government, which had arranged for the production of "real war films", The Battle of the Somme was "absorbing" and had attracted huge audiences. German troops recovered a letter from a British civilian, who had seen the film on 26 August and written to a soldier in France, describing the issue of a leaflet to each filmgoer that stated that the film was not entertainment but an official film. Having viewed the film, the writer was sure that it would enlighten the audience in a way never before achieved.[30]

Other films

During the second week of August, the King, Prime Minister and Lloyd George toured the Western Front and were filmed by Malins. The War Office released the film in October as The King Visits His Armies in the Great Advance.[31] Malins made a third film The Battle of the Ancre and the Advance of the Tanks which opened in January 1917.[32][lower-alpha 3] In the same month a German film With our Heroes on the Somme was shown but "lacked the immediacy" of the British film, being re-enactments at training establishments behind the lines, which received a lukewarm reception.[33] A booklet to accompany the film proclaimed that it depicted "the German will in war" and implied that the enemies of Germany were using colonial troops to undermine "German honour".[34] Malins' final feature film The German Retreat and the Battle of Arras was released in June 1917, showing the destruction of Péronne and the first British troops across the Somme, following-up the German withdrawal; the film failed to attract the audiences of 1916.[35]

Preservation

In 1920 the original nitrate negative was passed to the Imperial War Museum for preservation. A nitrate protection archive master was made in 1921 and an acetate safety master in 1931. The nitrate masters were destroyed in the 1970s after the onset of irreversible nitrate decomposition.[36] Excerpts have been taken for television documentaries, including The Great War (1964. BBC), The Great War and the Shaping of the 20th Century (1996, PBS) and The First World War (2003, Channel 4).[37] The film was offered on VHS in 1987, as the first title from the Imperial War Museum film archive to be released on video.[38] In 2005, The Battle of the Somme was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register for the preservation of global documentary heritage. The film was described by UNESCO as a "compelling documentary record of one of the key battles of the First World War [and] the first feature-length documentary film record of combat produced anywhere in the world" and had "played a major part in establishing the methodology of documentary and propaganda film."[39][36]

Recent screenings

On 22 October 2006, after a restoration project, a refined version of the film was screened at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, accompanied by the Philharmonia Orchestra performing an original orchestral score by Laura Rossi.[40] The restoration was later nominated for an Archive Restoration or Preservation Project award by the Federation of Commercial Audiovisual Libraries.[41] In November 2008, the restored film was released on DVD, to mark the 90th anniversary of the Armistice with Germany in 1918. The DVD included the score by Laura Rossi, an accompanying 1916 musical medley, a commentary by Roger Smither, a film archivist at the Imperial War Museum and interviews with Smither, Rossi, Toby Haggith (film archivist) and Stephen Horne (silent film musician) on the reconstruction of the contemporary medley; film fragments and missing scenes were also included in the DVD.[42]

In 2012, with the support of the Imperial War Museum, there were public screenings of the restored film accompanied by a live orchestra playing the soundtrack of Rossi's music.[43] Somme100 FILM has a target of a hundred performances of the film by amateur and professional orchestras in the centenary year, between July 2016 and July 2017.[44]

Notes

- "The ground where I stood gave a mighty convulsion. It rocked and swayed. I gripped hold of my tripod to steady myself. Then for all the world like a gigantic sponge, the earth rose high in the air to the height of hundreds of feet. Higher and higher it rose, and with a horrible grinding roar the earth settles back upon itself, leaving in its place a mountain of smoke."[2]

- Smither described this sequence as a symbol of the First World War, "one of the most famous images in the Imperial War Museum's collections" and that the identity of the "trench rescuer" is unknown.[19]

- "I'd like to see a tank come down the stalls/Lurching to rag-time tunes, or 'Home sweet home'/And there'd be no more jokes in Music-halls/To mock the riddled corpses round Bapaume." (Siegfried Sassoon, Blighters 1917).[32]

Footnotes

- Smither 2008, pp. 4–28.

- Malins 1920, p. 163.

- Badsey 1983, p. 104.

- Prior & Wilson 2005, p. 61.

- Duffy 2006, p. 93.

- Cave 1994, p. 51.

- Cave 1994, pp. 51–52.

- Cave 1994, pp. 53–54.

- Smither 2008, p. 3.

- Fraser, Robertshaw & Roberts 2009, p. 172.

- Philpott 2009, p. 302.

- Fraser, Robertshaw & Roberts 2009, p. 173.

- Reeves 1983, p. 467.

- Badsey 1983, p. 99.

- Haggith 2002, pp. 11–24.

- Badsey 1983, p. 108.

- Reeves 1997, p. 14.

- Badsey 1983, pp. 108, 100.

- Smither 2002, pp. 390–404.

- Reeves 1986, p. 14.

- Reeves 1986, p. 15.

- Reeves 1986, p. 472.

- Times 1916, p. 3.

- Badsey 1983, p. 110.

- Philpott 2009, p. 303.

- Feilding 1929, pp. 109–110.

- Evening Post 1916a, p. 2.

- Evening Post 1916b, p. 3.

- The Argus 1916, p. 18.

- Duffy 2006, pp. 93–94.

- Philpott 2009, p. 323.

- Philpott 2009, p. 369.

- Philpott 2009, p. 311.

- Sheffield 2003, p. 154.

- Philpott 2009, pp. 461–462.

- UNESCO 2012, p. 438.

- Smither 2004, p. 1.

- Smither 2004, p. 7.

- Smither 2004, p. 5.

- Times 2006, p. 17.

- FOCAL 2007.

- McWilliams 2009, pp. 130–133.

- Press release 20 January 2012

- Somme100 FILM - The Battle of the Somme Centenary Tour - 100 Performances of Battle of the Somme

References

Books

- Cave, N. (1994). Beaumont Hamel. Barnsley: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-398-0.

- Duffy, C. (2007) [2006]. Through German Eyes: The British and the Somme 1916 (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2202-9.

- Feilding, R. (1929). War Letters to a Wife: France and Flanders, 1915–1919. London: Medici. OCLC 752947224.

- Malins, G. H. (1920). How I Filmed the War : A Record of the Extraordinary Experiences of the Man Who Filmed the Great Somme Battles, etc. London: Herbert Jenkins. OCLC 246683398. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- Philpott, W. (2009). Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme and the Making of the Twentieth Century (1st ed.). London: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0108-9.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (2005). The Somme. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10694-7.

- Reeves, N. (1986). Official British Film Propaganda During the First World War. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-7099-4225-2.

- Fraser, Alastair; Robertshaw, Andrew; Roberts, Steve (2009). Ghosts on the Somme: Filming the Battle, June–July 1916. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-836-2.

- Sheffield, G. (2003). The Somme. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-36649-1.

- Smither, R. B. N. (2008). The Battle of the Somme (DVD viewing guide) (PDF) (2nd rev. ed.). London: Imperial War Museum. ISBN 978-0-901627-94-0. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- UNESCO (2012). Memory of the World: The Battle of the Somme. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-104237-9. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

Journals

- Badsey, S. (1983). "Battle of the Somme: British War-Propaganda". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 3 (2): 99–115. doi:10.1080/01439688300260081. ISSN 0143-9685.

- Haggith, Toby (2002). "Reconstructing the Musical Arrangement for "The Battle of the Somme"". Film History. 14 (1): 11–24. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 3815576.

- McWilliams, D. (April 2009). Dimitriu C. (ed.). "The Battle of the Somme (DVD review)" (PDF). Journal of Film Preservation (79/80). ISSN 1609-2694. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- Reeves, Nicholas (July 1983). "Film Propaganda and Its Audience: The Example of Britain's Official Films during the First World War". Journal of Contemporary History. 18 (3): 463–494. doi:10.1177/002200948301800306. ISSN 1461-7250. JSTOR 260547.

- Reeves, N. (1997). "Cinema, Spectatorship and Propaganda: 'Battle of the Somme' (1916) and its Contemporary Audience". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 17 (1). ISSN 1465-3451.

- Smither, R. B. N. (2002). ""Watch the Picture Carefully, and See If You Can Identify Anyone": Recognition in Factual Film of the First World War Period". Film History. 14 (3/4): 390–404. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 3815439.

Newspapers

- "Real War Pictures". The Argus. Melbourne. 14 October 1916. ISSN 1833-9700. Retrieved 6 October 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- "The Battle of the Somme (advertisement)". The Evening Post. Wellington, New Zealand. 12 October 1916. OCLC 320805360. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- "The Battle of the Somme: The Big Push in Pictures". The Evening Post. Wellington, New Zealand. 16 October 1916. OCLC 320805360. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- "War's Realities on the Cinema". The Times. London. 22 August 1916. ISSN 0140-0460.

- Geoff Brown (25 October 2006). "The Battle of the Somme". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

Websites

- http://www.focalint.org/ (2007). "Focal Award Nominations 2007". ISSN 1359-8708. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- Smither, R. B. N. (2004). "Memory of the World Register: The Battle of the Somme (nomination form)" (PDF). UNESCO. UNESCO. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

Further reading

Books

- Reeves, Nicholas (1996). "55 Through the Eye of the Camera: Contemporary Cinema Audiences and Their Experience of War in the Film "Battle of the Somme"". In Cecil, Hugh; Liddle, Peter H. Liddle (eds.). Facing Armageddon: The First World War Experienced (Pen & Sword paperback ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-506-9.

Journals

- Culbert, David (October 1995). "The Imperial War Museum: World War I Film Catalogue and The Battle of the Somme (video)". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 15 (4). ISSN 1465-3451.

- McKernan, L. (2002). "Propaganda, Patriotism and Profit: Charles Urban and British Official War Films in America during the First World War". Film History. 14 (3/4): 369–389. doi:10.2979/fil.2002.14.3-4.369. ISSN 0892-2160. JSTOR 3815438.

- Smither, R. (1993). ""A Wonderful Idea of the Fighting": The Question of Fakes in 'The Battle of the Somme'". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 13 (2). ISSN 0143-9685.

websites

- Tookey, C.; Walsh, D. (20 October 2006). "The Film Programme: The Battle of the Somme". BBC. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Battle of the Somme (film). |

- BBC article

- Filmography, British Topical Committee for War Films

- The Battle of the Somme (1916) on IMDb

- Viewpoint: The WW1 film over 20 million people went to see, 7 November 2014, BBC

- Screenings of the film in 2012 with live soundtrack of Laura Rossi's score

- Somme100 FILM - The Battle of the Somme Centenary Tour 2016

- Somme100 FILM - List of Performances of The Battle of the Somme in 2016