Judy Chicago

Judy Chicago (born Judith Sylvia Cohen; July 20, 1939) is an American feminist artist, art educator,[3] and writer known for her large collaborative art installation pieces about birth and creation images, which examine the role of women in history and culture. During the 1970s, Chicago founded the first feminist art program in the United States at California State University Fresno (formerly Fresno State College) and acted as a catalyst for Feminist art and art education.[4] Her inclusion in hundreds of publications in various areas of the world showcases her influence in the art community. Additionally, many of her books have been published in other countries, making her work more accessible to international readers. Chicago's work incorporates a variety of artistic skills, such as needlework, counterbalanced with labor-intensive skills such as welding and pyrotechnics. Chicago's most well known work is The Dinner Party, which is permanently installed in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum. The Dinner Party celebrates the accomplishments of women throughout history and is widely regarded as the first epic feminist artwork. Other notable art projects by Chicago include International Honor Quilt, The Birth Project,[5] Powerplay,[6] and The Holocaust Project.[7]

Judy Chicago | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Judith Sylvia Cohen[1] July 20, 1939 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of California, Los Angeles |

| Known for | Installation Painting Sculpture |

Notable work | The Dinner Party International Honor Quilt The Birth Project Powerplay The Holocaust Project |

| Movement | Contemporary Feminist art |

| Awards | Tamarind Fellowship, 1972 |

| Patron(s) | Holly Harp Elizabeth A. Sackler[2] |

Early personal life

Judy Chicago was born Judith Sylvia Cohen[1] in 1939, to Arthur and May Cohen, in Chicago, Illinois. Her father came from a twenty-three generation lineage of rabbis, including the Lithuanian Jewish Vilna Gaon. Unlike his family predecessors, Arthur became a labor organizer and a Marxist.[8] He worked nights at a post office and took care of Chicago during the day, while May, who was a former dancer, worked as a medical secretary.[1][8] Arthur's active participation in the American Communist Party, liberal views towards women and support of workers' rights strongly influenced Chicago's ways of thinking and belief.[9] During the McCarthyism era in the 1950s, Arthur was investigated, which made it difficult for him to find work and caused the family much turmoil.[8] In 1945, while Chicago was alone at home with her infant brother, Ben, an FBI agent visited their house. The agent began to ask the six-year-old Chicago questions about her father and his friends, but the agent was interrupted upon the return of May to the house.[9] Arthur's health declined and he died in 1953 from peritonitis. May would not discuss his death with her children and did not allow them to attend the funeral. Chicago did not come to terms with his death until she was an adult; in the early 1960s she was hospitalized for almost a month with a bleeding ulcer attributed to unresolved grief.[8]

May loved the arts, and instilled her passion for them in her children, as evident in Chicago's future as an artist, and brother Ben's eventual career as a potter. At age of three, Chicago began to draw and was sent to the Art Institute of Chicago to attend classes.[8][10] By the age of 5, Chicago knew that she "never wanted to do anything but make art"[10] and started attending classes at the Art Institute of Chicago.[11] She applied but was denied admission to the Art Institute,[9] and instead attended UCLA on a scholarship.[8]

Education and early career

While at UCLA, she became politically active, designing posters for the UCLA NAACP chapter and eventually became its corresponding secretary.[9] In June 1959, she met and became romantically linked with Jerry Gerowitz. She left school and moved in with him, for the first time having her own studio space. The couple hitch hiked to New York in 1959, just as Chicago's mother and brother moved to Los Angeles to be closer to her.[12] The couple lived in Greenwich Village for a time, before returning in 1960 from Los Angeles to Chicago so she could finish her degree. Chicago married Gerowitz in 1961.[13] She graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1962 and was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society. Gerowitz died in a car crash in 1963, which devastated and caused Chicago to suffer from an identity crisis until later that decade. She received her Master of Fine Arts from UCLA in 1964.[8]

While in grad school, Chicago's created a series that was abstract, yet easily recognized as male and female sexual organs. These early works were called Bigamy, and represented the death of her husband. One depicted an abstract penis, which was "stopped in flight" before it could unite with a vaginal form. Her professors, who were mainly men, were dismayed over these works.[13] Despite the use of sexual organs in her work, Chicago refrained from using gender politics or identity as themes.

In 1965, Chicago displayed work in her first solo show, at the Rolf Nelson Gallery in Los Angeles; Chicago was one of only four female artists to take part in the show.[14] In 1968, Chicago was asked why she did not participate in the "California Women in the Arts" exhibition at the Lytton Center, to which she answered, "I won't show in any group defined as Woman, Jewish, or California. Someday when we all grow up there will be no labels." Chicago began working in ice sculpture, which represented "a metaphor for the preciousness of life," another reference towards her husband's death.[15]

In 1969, the Pasadena Art Museum exhibited a series of Chicago's spherical acrylic plastic dome sculptures and drawings in an "experimental" gallery. Art in America noted that Chicago's work was at the forefront of the conceptual art movement, and the Los Angeles Times described the work as showing no signs of "theoretical New York type art."[15] Chicago would describe her early artwork as minimalist and as her trying to be "one of the boys."[16] Chicago would also experiment with performance art, using fireworks and pyrotechnics to create "atmospheres," which involved flashes of colored smoke being manipulated outdoors. Through this work she attempted to "feminize" and "soften" the landscape.[17]

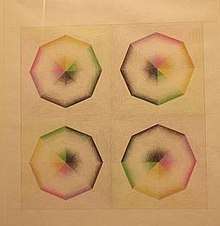

During this time, Chicago also began exploring her own sexuality in her work. She created the Pasadena Lifesavers, which was a series of abstract paintings that placed acrylic paint on Plexiglas. The works blended colors to create an illusion that the shapes "turn, dissolve, open, close, vibrate, gesture, wiggle," representing her own discovery that "I was multi-orgasmic." Chicago credited Pasadena Lifesavers, as being the major turning point in her work in relation to women's sexuality and representation.[17]

From Cohen to Gerowitz to Chicago: Name change

As Chicago made a name for herself as an artist and came to know herself as a woman, she no longer felt connected to her last name, Cohen. This was due to the late grief of the death of her father and the lost connection to her name through marriage, Judith Gerowitz, after her husband's death. She decided to change her last name to something independent of being connected to a man by marriage or heritage.[8] In 1965, she married sculptor Lloyd Hamrol. (They divorced in 1979.)[18] Gallery owner Rolf Nelson nicknamed her "Judy Chicago"[8] because of her strong personality and thick Chicago accent. She decided this would be her new name. In legally changing her surname from the ethnically charged Gerowitz to the ethnically neutral Chicago, she freed herself from a certain social identity.[19] Chicago was appalled that her new husband's signature was required to change her name legally.[18] To celebrate the name change, she posed for the exhibition invitation dressed like a boxer, wearing a sweatshirt with her new last name on it.[17] She also posted a banner across the gallery at her 1970 solo show at California State University at Fullerton, that read: "Judy Gerowitz hereby divests herself of all names imposed upon her through male social dominance and chooses her own name, Judy Chicago."[18] An advertisement with the same statement was also placed in Artforum's October 1970 issue.[20]

Artistic career

The feminist art movement and the 1970s

In 1970, Chicago decided to teach full-time at Fresno State College, hoping to teach women the skills needed to express the female perspective in their work.[21] At Fresno, she planned a class that would consist only of women, and she decided to teach off campus to escape "the presence and hence, the expectations of men."[22] She taught the first women's art class in the fall of 1970 at Fresno State College. It became the Feminist Art Program, a full 15-unit program, in the spring of 1971. This was the first feminist art program in the United States. Fifteen students studied under Chicago at Fresno State College: Dori Atlantis, Susan Boud, Gail Escola, Vanalyne Green, Suzanne Lacy, Cay Lang, Karen LeCocq, Jan Lester, Chris Rush, Judy Schaefer, Henrietta Sparkman, Faith Wilding, Shawnee Wollenman, Nancy Youdelman, and Cheryl Zurilgen. Together, as the Feminist Art Program, these women rented and refurbished an off-campus studio at 1275 Maple Avenue in downtown Fresno. Here they collaborated on art, held reading groups, and discussion groups about their life experiences which then influenced their art. All of the students and Chicago contributed $25 per month to rent the space and to pay for materials.[23] Later, Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro reestablished the Feminist Art Program at California Institute of the Arts. After Chicago left for Cal Arts, the class at Fresno State College was continued by Rita Yokoi from 1971 to 1973, and then by Joyce Aiken in 1973, until her retirement in 1992.[nb 1]

Chicago is considered one of the "first-generation feminist artists," a group that also includes Mary Beth Edelson, Carolee Schneeman, and Rachel Rosenthal. They were part of the Feminist art movement in Europe and the United States in the early 1970s to develop feminist writing and art.[25]

Chicago became a teacher at the California Institute for the Arts, and was a leader for their Feminist Art Program. In 1972, the program created Womanhouse, alongside Miriam Schapiro, which was the first art exhibition space to display a female point of view in art.[18] With Arlene Raven and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Chicago co-founded the Los Angeles Woman's Building in 1973.[26] This art school and exhibition space was in a structure named after a pavilion at the 1893 World's Colombian Exhibition that featured art made by women from around the world.[27] This housed the Feminist Studio Workshop, described by the founders as "an experimental program in female education in the arts. Our purpose is to develop a new concept of art, a new kind of artist and a new art community built from the lives, feelings, and needs of women."[16][28] During this period, Chicago began creating spray-painted canvas, primarily abstract, with geometric forms on them. These works evolved, using the same medium, to become more centered around the meaning of the "feminine." Chicago was strongly influenced by Gerda Lerner, whose writings convinced her that women who continued to be unaware and ignorant of women's history would continue to struggle independently and collectively.[18]

Womanhouse

Womanhouse was a project that involved Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. It began in the fall of 1971 and was the first public exhibition of Feminist Art. They wanted to start the year with a large scale collaborative project that involved woman artists who spent much of their time talking about their problems as women. They used those problems as fuel and dealt with them while working on the project. Judy thought that female students often approach art-making with an unwillingness to push their limits due to their lack of familiarity with tools and processes, and an inability to see themselves as working people. In this environment, female artists experimented with women's conventional roles and experiences and how these could be displayed. "The aim of the Feminist Art Program is to help women restructure their personalities to be more consistent with their desires to be artists and to help them build their art-making out of their experiences as women."[29] Womanhouse is a "true" dramatic representation of woman's experience beginning in childhood, encompassing the struggles at home, with housework, menstruation, marriage, etc.[19]

In 1975, Chicago's first book, Through the Flower, was published; it "chronicled her struggles to find her own identity as a woman artist."[14]

The Dinner Party

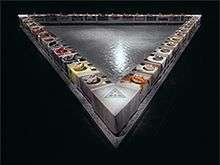

Chicago decided to take Lerner's lesson to heart and took action to teach women about their history. This action would become Chicago's masterpiece, The Dinner Party, now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum.[30] It took her five years and cost about $250,000 to complete.[11] First, Chicago conceived the project in her Santa Monica studio: a large triangle, which measures 48-feet by 43-feet by 36-feet, consisting of 39 place settings.[18] Each place setting commemorates a historical or mythical female figure, such as artists, goddesses, activists, and martyrs. Thirteen women are represented on each side, comparable with the number said to be at a traditional witches' coven and triple the amount of attendees at the Last Supper. The embroidered table runners are stitched in the style and technique of the woman's time.[31] Numerous other names of women are engraved in the "Heritage Floor" upon which the piece sits. The project came into fruition with the assistance of over 400 people, mainly women, who volunteered to assist in needlework, creating sculptures and other aspects of the process.[32] When The Dinner Party was first constructed, it was a traveling exhibition. Through the Flower, her non-profit organization, was originally created to cover the expense of the creation and travel of the artwork. Jane Gerhard dedicated a book to Judy Chicago and The Dinner Party, entitled "The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and The Power of Popular Feminism, 1970–2007."[33]

Inspiration for The Dinner Party came from personal experience where Chicago found herself at a male dominated event. This event included highly educated men and women, however the men dominated the conversation and essence of the space. Chicago highlights important women that are often overlooked, giving credit to those who have stepped up for women's rights. This work is less of a statement and more of an honoring and a form of gratitude and inspiration. Chicago wanted the piece to teach about the struggle for power and equality women have endured in a male dominant societies. It considers the possibility of a meeting between powerful women and how this could change human history.

Many art critics, including Hilton Kramer from The New York Times, were unimpressed by her work.[34] Mr. Kramer felt Chicago's intended vision was not conveyed through this piece and "it looked like an outrageous libel on the female imagination."[34] Although art critics felt her work lacked depth and the dinner party was just "vaginas on plates," it was popular and captivated the general public. Chicago debuted her work in six countries on three continents. She reached over a million people through her artwork. Her work might not have pleased critics but its feminist message captivated the public and it honored the its featured 39 historical figures and 999 other women.

Birth Project and PowerPlay

From 1980 until 1985, Chicago created Birth Project. It took five years to create. The piece used images of childbirth to celebrate woman's role as mother. Chicago was inspired to create this collective work because of the lack of imagery and representation of birth in the art world.[35] The installation reinterpreted the Genesis creation narrative, which focused on the idea that a male god created a male human, Adam, without the involvement of a woman.[32] Chicago described the piece as revealing a "primordial female self hidden among the recesses of my soul...the birthing woman is part of the dawn of creation."[10] 150 needleworkers from the United States, Canada and New Zealand assisted in the project, working on 100 panels, by quilting, macrame, embroidery and other techniques. The size of the piece means it is rarely displayed in its entirety. The majority of the pieces from Birth Project are held in the collection of the Albuquerque Museum.[32]

Chicago was not personally interested in motherhood. While she admired the women who chose this path, she did not find it right for herself. As recently as 2012, she said, "There was no way on this earth I could have had children and the career I've had."[11]

After Birth Project, Chicago returned to independent studio work. She created PowerPlay, a series of drawings, weavings, paintings, cast paper and bronze reliefs. Through the series, Chicago replaced the male gaze with a feminist one, exploring the construct of masculinity and how power has affected men.[36]

A new kind of collaboration and The Holocaust Project

In the mid-1980s Chicago's interests "shifted beyond 'issues of female identity' to an exploration of masculine power and powerlessness in the context of the Holocaust."[37] Chicago's The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985–93)[37] is a collaboration with her husband, photographer Donald Woodman, whom she married on New Year's Eve 1985. Although Chicago's previous husbands were both Jewish, it wasn't until she met Woodman that she began to explore her own Jewish heritage. Chicago met poet Harvey Mudd, who had written an epic poem about the Holocaust. Chicago was interested in illustrating the poem, but decided to create her own work instead, using her own art, visual and written. Chicago worked alongside her husband to complete the piece, which took eight years to finish.[32] The piece, which documents victims of the Holocaust, was created during a time of personal loss in Chicago's life: the death of her brother Ben, from Lou Gehrig's disease, and the death of her mother from cancer.[38]

Chicago used the tragic event of the Holocaust as a prism through which to explore victimization, oppression, injustice, and human cruelty.[33] To seek inspiration for the project, Chicago and Woodman watched the documentary Shoah, which comprises interviews with Holocaust survivors at Nazi concentration camps and other relevant Holocaust sites.[38] They also explored photo archives and written pieces about the Holocaust.[39] They spent several months touring concentration camps and visited Israel.[37] Chicago brought other issues into the work, such as environmentalism, Native American genocide,[10] and the Vietnam War. With these subjects Chicago sought to relate contemporary issues to the moral dilemma behind the Holocaust.[38] This aspect of the work caused controversy within the Jewish community, due to the comparison of the Holocaust to these other historical and contemporary concerns.[10] The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light consists of sixteen large scale works made of a variety of mediums including: tapestry, stained glass, metal work, wood work, photography, painting, and the sewing of Audrey Cowan. The exhibit ends with a piece that displays a Jewish couple at Sabbath. The piece comprises 3000 square feet, providing a full exhibition experience for the viewer.[38] The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light was exhibited for the first time in October 1993 at the Spertus Museum in Chicago.[38] Most of the work from the piece is held at the Holocaust Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[2]

Over the next six years, Chicago created works that explored the experiences of concentration camp victims.[37] Galit Mana of Jewish Renaissance magazine notes, "This shift in focus led Chicago to work on other projects with an emphasis on Jewish tradition", including Voices from the Song of Songs (1997), where Chicago "introduces feminism and female sexuality into her representation of strong biblical female characters."[37]

Current work and life

In 1985, Chicago was remarried, to photographer Donald Woodman. To celebrate the couple's 25th wedding anniversary, Chicago created a "Renewal Ketubah" in 2010.[14]

In 1994, Judy Chicago started "Resolutions: A Stitch in Time" which took 6 years to complete. The public audience later got to see this project at the Museum of Art and Design in New York in 2000.[40]

In 1996, Chicago and Woodman moved into the historic Belen Hotel, an historic railroad hotel in Belen, New Mexico which Woodman had spent three years converting into a home.[40]

Chicago's archives are held at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College, and her collection of women's history and culture books are held in the collection of the University of New Mexico. In 1999, Chicago received the UCLA Alumni Professional Achievement Award, and has been awarded honorary degrees from Lehigh University, Smith College, Duke University[41] and Russell Sage College.[2] In 2004, Chicago received a Visionary Woman Award from Moore College of Art & Design.[42] Chicago was named a National Women's History Project honoree for Women's History Month in 2008.[43] Chicago donated her collection of feminist art educational materials to Penn State University in 2011.[44] She lives in New Mexico.[45] In the fall of 2011, Chicago returned to Los Angeles for the opening of the "Concurrents" exhibition at the Getty Museum. For the exhibition, she returned to the Pomona College football field, where in the late 1960s she had held a firework-based installation, and performed the piece again.[46]

Chicago had two solo exhibitions in the United Kingdom in 2012, one in London and another in Liverpool.[37] The Liverpool exhibition included the launch of Chicago's book about Virginia Woolf. Once a peripheral part of her artistic expression, Chicago now considers writing to be well integrated into her career.[37] That year, she was also awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Palm Springs Art Fair.[40]

She was interviewed for the film !Women Art Revolution.[47]

Chicago strives to push herself, exploring new directions for her art; she even attended car-body school to learn to air-brush and has recently begun to work in glass.[11] Taking such risks is easier to do when one lives by Chicago's philosophy: "I'm not career driven. Damien Hirst's dots sold, so he made thousands of dots. I would, like, never do that! It wouldn't even occur to me."[11] Chicago's subject matter, however, has broadened from the focus of The Dinner Party. In the words of the artist: "I guess you could say that my eyes were lifted from my vagina."[11]

Chicago has permanent collections in numerous museums around the world. Those include, The British Museum, The Brooklyn Museum, The Getty Trust, The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, New Mexico Museum of Art, The National Gallery of Art, The National Museum of Women in the Arts, The Penn Academy of the Fine Arts, and The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.[48]

In her interview with Gloria Steinem, Chicago spoke of her "goal as an artist", stating that it "…has been to create images in which the female experience is the path to the universal, as opposed to learning everything through the male gaze."[49]

Style and work

Chicago trained herself in "macho arts," taking classes in auto body work, boat building, and pyrotechnics. Through auto body work she learned spray painting techniques and the skill to fuse color and surface to any type of media, which would become a signature of her later work. The skills learned through boat building would be used in her sculpture work, and pyrotechnics would be used to create fireworks for performance pieces. These skills allowed Chicago to bring fiberglass and metal into her sculpture, and eventually she would become an apprentice under Mim Silinsky to learn the art of porcelain painting, which would be used to create works in The Dinner Party. Chicago also added the skill of stained glass to her artistic tool belt, which she used for The Holocaust Project.[18] Photography became more present in Chicago's work as her relationship with photographer Donald Woodman developed.[39] Since 2003, Chicago has been working with glass.[45]

Collaboration is a major aspect of Chicago's installation works. The Dinner Party, The Birth Project and The Holocaust Project were all completed as a collaborative process with Chicago and hundreds of volunteer participants. Volunteer artisans skills vary, often connected to "stereotypical" women's arts such as textile arts.[18][38] Chicago makes a point to acknowledge her assistants as collaborators, a task at which other artists have notably failed.[11][50]

Through the Flower

In 1978, Chicago founded Through the Flower, a non-profit feminist art organization. The organization seeks to educate the public about the importance of art and how it can be used as a tool to emphasize women's achievements. Through the Flower also serves as the maintainer of Chicago's works, having handled the storage of The Dinner Party, before it found a permanent home at the Brooklyn Museum. The organization also maintained The Dinner Party Curriculum, which serves as a "living curriculum" for education about feminist art ideas and pedagogy. The online aspect of the curriculum was donated to Penn State University in 2011.[45]

Teaching career

Judy Chicago became aware of the sexism that was rampant in modern art institutions, museums, and schools while getting her undergraduate and graduate degree at UCLA in the 1960s. Ironically, she didn't challenge this observation as an undergrad. In fact, she did quite the opposite by trying to match – both in her artwork and in her personal style – what she thought of as masculinity in the artistic styles and habits of her male counterparts. Not only did she begin to work with heavy industrial materials, but she also smoked cigars, dressed “masculine”, and attended motorcycle shows.[51] This awareness continued to grow as she recognized how society did not see women as professional artists in the same way they recognized men. Angered by this, Chicago channeled this energy and used it to strengthen her feminist values as a person and teacher. While most teachers based their lessons on technique, visual forms, and color, the foundation for Chicago's teachings were on the content and social significance of the art, especially in feminism.[52] Stemming from the male-dominated art community Chicago studied with for so many years, she valued art based on research, social or political views, and/or experience. She wanted her students to grow into their art professions without having to sacrifice what womanhood meant to them. Chicago developed an art education methodology in which "female-centered content," such as menstruation and giving birth, is encouraged by the teacher as "personal is political" content for art.[53] Chicago advocates the teacher as facilitator by actively listening to students in order to guide content searches and the translation of content into art. She refers to her teaching methodology as "participatory art pedagogy."[54]

The art created in the Feminist Art Program and Womanhouse introduced perspectives and content about women's lives that had been taboo topics in society, including the art world.[55][56] In 1970 Chicago developed the Feminist Art Program at California State University, Fresno, and has implemented other teaching projects that conclude with an art exhibition by students such as Womanhouse with Miriam Schapiro at CalArts, and SINsation in 1999 at Indiana University, From Theory to Practice: A Journey of Discovery at Duke University in 2000, At Home: A Kentucky Project with Judy Chicago and Donald Woodman at Western Kentucky University in 2002, Envisioning the Future at California Polytechnic State University and Pomona Arts Colony in 2004, and Evoke/Invoke/Provoke at Vanderbilt University in 2005.[57] Several students involved in Judy Chicago's teaching projects established successful careers as artists, including Suzanne Lacy, Faith Wilding, and Nancy Youdelman.

In the early 2000s, Chicago organized her teaching style into three parts: preparation, process, and art-making.[52] Each has a specific purpose and is crucial. During the preparation phase, students identify a deep personal concern and then research that issue. In the process phase, students gather together in a group to discuss the materials they plan on using and the content of their work. Finally, in the art-making phase, students find materials, sketch, critique, and produce art.

Books by Chicago

- The Dinner Party: A Symbol of our Heritage. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday (1979). ISBN 0-385-14567-5.

- with Susan Hill. Embroidering Our Heritage: The Dinner Party Needlework. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday (1980). ISBN 0-385-14569-1.

- The Birth Project. New York: Doubleday (1985). ISBN 0-385-18710-6.

- Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist. New York: Penguin (1997). ISBN 0-14-023297-4.

- Kitty City: A Feline Book of Hours. New York: Harper Design (2005). ISBN 0-06-059581-7.

- Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist. Lincoln: Authors Choice Press (2006). ISBN 0-595-38046-8.

- with Frances Borzello. Frida Kahlo: Face to Face. New York: Prestel USA (2010). ISBN 3-7913-4360-2.

- Institutional Time: A Critique of Studio Art Education. New York: The Monacelli Press (2014). ISBN 9781580933667.

Notes

References

- Levin in Bloch and Umansky, 305

- Felder and Rosen, 284.

- Chicago, Judy. (2014). Institutional Time. The Monacelli Press.

- Broude, Norma; Garrard, Mary D.; Brodsky, Judith K. (1996). The power of feminist art : the American movement of the 1970s, history and impact. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-2659-8. OCLC 35746646.

- Chicago, Judy (1985-03-05). The Birth Project (First ed.). Place of publication not identified: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385187107.

- Chicago, Judy; Gallery, David Richard; Katz, Jonathan D. (2012). Judy Chicago PowerPlay. Santa Fe, NM. ISBN 9780983931232.

- Chicago, Judy; Woodman, Donald (1993-10-01). Holocaust Project: From Darkness Into Light (1st ed.). New York, N.Y., U.S.A u.a: Viking. ISBN 9780670842124.

- Felder and Rosen, 279.

- Levin in Bloch and Umansky, 306

- Wydler and Lippard, 5.

- Cooke, Rachel (3 November 2012). "The art of Judy Chicago". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- Levin in Bloch and Umansky, 308

- Levin in Bloch and Umansky, 311

- Chicago, Judy. "Illustrated Career History". Archived from the original on 2014-02-27.

- Levin in Bloch and Umansky, 314

- Lewis and Lewis, 455.

- Levin in Bloch and Umansky, 315

- Felder and Rosen, 280.

- Soussloff, Catherine (1999). Jewish Identity in Modern Art History. Berkeley, CA: U of California Press.

- Levin, Becoming Judy Chicago; A Biography of the Artist, p. 139

- Levin in Bloch and Umansky, 317

- Levin in Bloch and Umansky, 318

- 1939–, Chicago, Judy (2014). Institutional time : a critique of studio art education. ISBN 9781580933667. OCLC 851420315.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Dr. Laura Meyer; Nancy Youdelman. "A Studio of Their Own: The Legacy of the Fresno Feminist Art Experiment". A Studio of their Own. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- Thomas Patin and Jennifer McLerran (1997). Artwords: A Glossary of Contemporary Art Theory. Westport, CT: Greenwood. p. 55. Retrieved 8 January 2014. via Questia (subscription required)

- "Woman's Building records, 1970–1992". Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- "Judy Chicago". SFMOMA. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- Moravec, Michelle (2013). "Looking For Lyotard, Beyond the Genre of Feminist Manifesto" (PDF). Trespassing. 1 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- Schapiro, Miriam; Chicago, Judy. "Womanhouse catalog essay" (PDF). Womanhouse. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- "The Dinner Party". Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Rozsika., Parker (1984). The subversive stitch : embroidery and the making of the feminine. London: Women's Press. ISBN 0704338831. OCLC 11237744.

- Felder and Rosen, 281.

- "Through the Flower and Judy Chicago". www.throughtheflower.org. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- Pilat, Kasia (2018-02-28). "From 'Vicious' to Celebratory: The Times's Reviews of Judy Chicago's 'The Dinner Party'". The New York Times.

- Bennetts, Leslie (1985-04-08). "JUDY CHICAGO: WOMEN'S LIVES AND ART". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- "Judy Chicago". Jewish Virtual Library. 2012. Retrieved 15 Jan 2011.

- Galit Mana (October 2012). "Judy Chicago in the UK". Jewish Renaissance. 12 (1): 42–43.

- Felder and Rosen, 282.

- Wylder and Lippard, 6

- "Judy Chicago". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-25. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- Debra Wacks (2012). "Judy Chicago". Jewish Women's Archives. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- "Visionary Woman Awards". Support Moore. Moore College of Art & Design. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "Judy Chicago". 2008 Honorees. National Women's History Month Project. 2008. Retrieved 15 Jan 2011.

- "The Judy Chicago Art Education Collection | Penn State". judychicago.arted.psu.edu. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- "Penn State Receives Judy Chicago Feminist Art Education Collections". Local News. Gant Daily. 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Jori Finkel (2011). "Q&A Judy Chicago". Censorship. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Anon 2018

- "Judy Chicago | Artstor". www.artstor.org. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- "Judy Chicago" by Gloria Steinem, December/January 2018 issue of "Interview", pp. 28–31

- Gerhard, Jane (2013). The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the power of popular feminism. 1970–2007. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. pp. 2, 228. ISBN 978-0-8203-3675-6.

- Chicago, Judy; Meyer, Laura (1995-12-28). "Judy Chicago, Feminist Artist and Educator". Women & Therapy. 17 (1–2): 125–140. doi:10.1300/j015v17n01_13. ISSN 0270-3149.

- Keifer-Boyd, Karen (January 2007). "From Content to Form: Judy Chicago's Pedagogy with Reflections by Judy Chicago". Studies in Art Education. 48 (2): 134–154. doi:10.1080/00393541.2007.11650096. ISSN 0039-3541.

- Chicago, Judy, (n.d.). Art Practice/Art Pedagogy, Judy Chicago Art Education Collection, Penn State, Box 11, Folder 6, page 1 at http://judychicago.arted.psu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Art-Practice-Art-PedagogyTranscript-and-Slide-Presentation-Boxx-11-6.pdf.

- Keifer-Boyd, K. (2007). From content to form: Judy Chicago's pedagogy with reflections by Judy Chicago. Studies in Art Education: A Journal of Issues and Research in Art Education, 48(2), 133–153.

- Fields, Jill (Ed.). (2012). Entering the picture: Judy Chicago, The Fresno Feminist Art Program, and the collective visions of women artists. New York: Routledge.

- Gerhard, Jane F. (2013). The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the power of popular feminism. 1970–2007. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Chicago, Judy. (2014) Institutional Time: A Critique of Studio Art Education. New York, NY: Monacelli Press.

Sources

- Anon (2018). "Artist, Curator & Critic Interviews". !Women Art Revolution - Spotlight at Stanford. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bloch, Avital (editor) and Lauri Umansky (editor). Impossible to Hold: Women and Culture in the 1960s. New York: NYU Press (2005). ISBN 0-8147-9910-8.

- Felder, Deborah G. and Diana Rosen. Fifty Jewish Women Who Changed the World. Yucca Valley: Citadel (2005). ISBN 0-8065-2656-4.

- Lewis, Richard L. and Susan Ingalls Lewis. The Power of Art. Florence: Wadsworth (2008). ISBN 0-534-64103-2.

- Wylder, Thompson Viki D. and Lucy R. Lippard. Judy Chicago: Trials and Tributes. Tallahassee: Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts (1999). ISBN 1-889282-05-7.

Further reading

- Dickson, Rachel (ed.), with contributions by Judy Battalion, Frances Borzello, Diane Gelon, Alexandra Kokoli, Andrew Perchuk. Judy Chicago. Lund Humpries, Ben Uri (2012). ISBN 978-1-84822-120-8.

- Levin, Gail. Becoming Judy Chicago: A Biography of the Artist. New York: Crown (2007). ISBN 1-4000-5412-5.

- Lippard, Lucy, Elizabeth A. Sackler, Edward Lucie-Smith and Viki D. Thompson Wylder. Judy Chicago. ISBN 0-8230-2587-X.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward. Judy Chicago, An American Vision. New York: Watson-Guptill (2000). ISBN 0-8230-2585-3.

- Right Out of History: Judy Chicago. DVD. Phoenix Learning Group (2008).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Judy Chicago. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Judy Chicago |

- Official website

- Judy Chicago on Through the Flower

- Judy Chicago Art Education Collection at Pennsylvania State

- Papers, 1947–2004 (inclusive), 1957–2004 (bulk). Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- International Honor Quilt Collection, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

- Judy Chicago Visual Archive at National Museum of Women in the Arts