Helen Keller

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880 – June 1, 1968) was an American author, political activist, and lecturer. She was the first deaf-blind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree. The story of Keller and her teacher, Anne Sullivan, was made famous by Keller's autobiography, The Story of My Life, and its adaptations for film and stage, The Miracle Worker. Her birthplace in West Tuscumbia, Alabama, is now a museum[1] and sponsors an annual "Helen Keller Day". Her June 27 birthday is commemorated as Helen Keller Day in Pennsylvania and, in the centenary year of her birth, was recognized by a presidential proclamation from US President Jimmy Carter.

Helen Keller | |

|---|---|

Helen Keller holding a magnolia, ca. 1920 | |

| Born | Helen Adams Keller June 27, 1880 Tuscumbia, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | June 1, 1968 (aged 87) Arcan Ridge, Easton, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Resting place | Washington National Cathedral |

| Occupation | Author, political activist, lecturer |

| Education | Radcliffe College (BA) |

| Notable works | The Story of My Life |

| Signature | |

A prolific author, Keller was well-traveled and outspoken in her convictions. A member of the Socialist Party of America and the Industrial Workers of the World, she campaigned for women's suffrage, labor rights, socialism, antimilitarism, and other similar causes. She was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame in 1971 and was one of twelve inaugural inductees to the Alabama Writers Hall of Fame on June 8, 2015.[2]

Early childhood and illness

Helen Adams Keller was born on June 27, 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama.[3] Her family lived on a homestead, Ivy Green,[1] that Helen's grandfather had built decades earlier.[4] She had four siblings: two full siblings, Mildred Campbell (Keller) Tyson and Phillip Brooks Keller, and two older half-brothers from her father's prior marriage, James McDonald Keller and William Simpson Keller.[5][6]

Her father, Arthur Henley Keller (1836–1896),[7] spent many years as an editor of the Tuscumbia North Alabamian and had served as a captain in the Confederate Army.[3][4] The family were part of the slaveholding elite before the war, but lost status later.[4] Her mother, Catherine Everett (Adams) Keller (1856–1921), known as "Kate",[8] was the daughter of Charles W. Adams, a Confederate general. Her paternal lineage was traced to Casper Keller, a native of Switzerland.[9][10] One of Helen's Swiss ancestors was the first teacher for the deaf in Zurich. Keller reflected on this irony in her first autobiography, stating "that there is no king who has not had a slave among his ancestors, and no slave who has not had a king among his."[9]

At 19 months old, Keller contracted an unknown illness described by doctors as "an acute congestion of the stomach and the brain",[11] which might have been scarlet fever or meningitis.[3][12] The illness left her both deaf and blind. She lived, as she recalled in her autobiography, "at sea in a dense fog".[13]

At that time, Keller was able to communicate somewhat with Martha Washington, the two-years older daughter of the family cook, who understood her signs;[14]:11 by the age of seven, Keller had more than 60 home signs to communicate with her family, and could distinguish people by the vibration of their footsteps.[15] She tyrannized the African-American servants.[4]

In 1886, Keller's mother, inspired by an account in Charles Dickens' American Notes of the successful education of another deaf and blind woman, Laura Bridgman, dispatched the young Keller, accompanied by her father, to seek out physician J. Julian Chisolm, an eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist in Baltimore, for advice.[16][4]

Chisholm referred the Kellers to Alexander Graham Bell, who was working with deaf children at the time. Bell advised them to contact the Perkins Institute for the Blind, the school where Bridgman had been educated, which was then located in South Boston. Michael Anagnos, the school's director, asked a 20-year-old alumna of the school, Anne Sullivan, herself visually impaired, to become Keller's instructor. It was the beginning of a nearly 50-year-long relationship during which Sullivan evolved into Keller's governess and eventually her companion.[14]

Sullivan arrived at Keller's house on March 5, 1887, a day Keller would forever remember as my soul's birthday.[13] Sullivan immediately began to teach Helen to communicate by spelling words into her hand, beginning with "d-o-l-l" for the doll that she had brought Keller as a present. Keller was frustrated, at first, because she did not understand that every object had a word uniquely identifying it. When Sullivan was trying to teach Keller the word for "mug", Keller became so frustrated she broke the mug.[17] But soon she began imitating Sullivan's hand gestures. "I did not know that I was spelling a word or even that words existed," Keller remembered. "I was simply making my fingers go in monkey-like imitation."[18]

Keller's breakthrough in communication came the next month when she realized that the motions her teacher was making on the palm of her hand, while running cool water over her other hand, symbolized the idea of "water". Writing in her autobiography, The Story of My Life, Keller recalled the moment: "I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten — a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that w-a-t-e-r meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. The living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, set it free!"[13] Keller then nearly exhausted Sullivan, demanding the names of all the other familiar objects in her world.

Helen Keller was viewed as isolated but was very in touch with the outside world. She was able to enjoy music by feeling the beat and she was able to have a strong connection with animals through touch. She was delayed at picking up language, but that did not stop her from having a voice.[19]

Formal education

In May 1888, Keller started attending the Perkins Institute for the Blind. In 1894, Keller and Sullivan moved to New York to attend the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf, and to learn from Sarah Fuller at the Horace Mann School for the Deaf. In 1896, they returned to Massachusetts, and Keller entered The Cambridge School for Young Ladies before gaining admittance, in 1900, to Radcliffe College of Harvard University,[20] where she lived in Briggs Hall, South House. Her admirer, Mark Twain, had introduced her to Standard Oil magnate Henry Huttleston Rogers, who, with his wife Abbie, paid for her education. In 1904, at the age of 24, Keller graduated as a member of Phi Beta Kappa[21] from Radcliffe, becoming the first deaf-blind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree. She maintained a correspondence with the Austrian philosopher and pedagogue Wilhelm Jerusalem, who was one of the first to discover her literary talent.[22]

Determined to communicate with others as conventionally as possible, Keller learned to speak and spent much of her life giving speeches and lectures on aspects of her life. She learned to "hear" people's speech using the Tadoma method, which means using her fingers to feel the lips and throat of the speaker—her sense of touch had heightened. She became proficient at using braille[23] and reading sign language with her hands as well. Shortly before World War I, with the assistance of the Zoellner Quartet, she determined that by placing her fingertips on a resonant tabletop she could experience music played close by.[24]

Example of her lectures

On January 22, 1916, Keller and Sullivan traveled to the small town of Menomonie in western Wisconsin to deliver a lecture at the Mabel Tainter Memorial Building. Details of her talk were provided in the weekly Dunn County News on January 22, 1916:

A message of optimism, of hope, of good cheer, and of loving service was brought to Menomonie Saturday—a message that will linger long with those fortunate enough to have received it. This message came with the visit of Helen Keller and her teacher, Mrs. John Macy, and both had a hand in imparting it Saturday evening to a splendid audience that filled The Memorial. The wonderful girl who has so brilliantly triumphed over the triple afflictions of blindness, dumbness and deafness, gave a talk with her own lips on "Happiness", and it will be remembered always as a piece of inspired teaching by those who heard it.[25]

Companions

Anne Sullivan stayed as a companion to Helen Keller long after she taught her. Sullivan married John Macy in 1905, and her health started failing around 1914. Polly Thomson (February 20, 1885[26] – March 21, 1960) was hired to keep house. She was a young woman from Scotland who had no experience with deaf or blind people. She progressed to working as a secretary as well, and eventually became a constant companion to Keller.[27]

Keller moved to Forest Hills, Queens, together with Sullivan and Macy, and used the house as a base for her efforts on behalf of the American Foundation for the Blind.[28] "While in her thirties Helen had a love affair, became secretly engaged, and defied her teacher and family by attempting an elopement with the man she loved."[29] He was the finger-spelling socialist[4] "Peter Fagan, a young Boston Herald reporter who was sent to Helen's home to act as her private secretary when lifelong companion, Anne, fell ill." At the time, her father had died and Sullivan was recovering in Lake Placid and Puerto Rico. Keller had moved with her mother in Montgomery, Alabama.[4]

Anne Sullivan died in 1936, with Keller holding her hand,[30]:255 after falling into a coma as a result of coronary thrombosis.[31]:266 Keller and Thomson moved to Connecticut. They traveled worldwide and raised funds for the blind. Thomson had a stroke in 1957 from which she never fully recovered, and died in 1960. Winnie Corbally, a nurse originally hired to care for Thomson in 1957, stayed on after Thomson's death and was Keller's companion for the rest of her life.[28]

Political activities

—Helen Keller, 1911[32]

Keller went on to become a world-famous speaker and author. She is remembered as an advocate for people with disabilities, amid numerous other causes. The deaf community was widely impacted by her. She traveled to twenty-five different countries giving motivational speeches about Deaf people's conditions.[33] She was a suffragist, pacifist, radical socialist, birth control supporter, and opponent of Woodrow Wilson. In 1915, she and George A. Kessler founded the Helen Keller International (HKI) organization. This organization is devoted to research in vision, health, and nutrition. In 1916 she sent money to the NAACP ashamed of the Southern un-Christian treatment of "colored people".[4] In 1920, she helped to found the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Keller traveled to over 40 countries with Sullivan, making several trips to Japan and becoming a favorite of the Japanese people. Keller met every U.S. president from Grover Cleveland to Lyndon B. Johnson and was friends with many famous figures, including Alexander Graham Bell, Charlie Chaplin and Mark Twain. Keller and Twain were both considered political radicals allied with leftist politics.[34]

Keller was a member of the Socialist Party and actively campaigned and wrote in support of the working class from 1909 to 1921. Many of her speeches and writings were about women's right to vote and the impacts of war; in addition, she supported causes that opposed military intervention.[35] She had speech therapy in order to have her voice heard better by the public. When the Rockefeller-owned press refused to print her articles, she protested until her work was finally published.[31] She supported Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs in each of his campaigns for the presidency. Before reading Progress and Poverty, Helen Keller was already a socialist who believed that Georgism was a good step in the right direction.[36] She later wrote of finding "in Henry George's philosophy a rare beauty and power of inspiration, and a splendid faith in the essential nobility of human nature".[37]

Keller claimed that newspaper columnists who had praised her courage and intelligence before she expressed her socialist views now called attention to her disabilities. The editor of the Brooklyn Eagle wrote that her "mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development". Keller responded to that editor, referring to having met him before he knew of her political views:

At that time the compliments he paid me were so generous that I blush to remember them. But now that I have come out for socialism he reminds me and the public that I am blind and deaf and especially liable to error. I must have shrunk in intelligence during the years since I met him. ... Oh, ridiculous Brooklyn Eagle! Socially blind and deaf, it defends an intolerable system, a system that is the cause of much of the physical blindness and deafness which we are trying to prevent.[38]

Keller joined the Industrial Workers of the World (the IWW, known as the Wobblies) in 1912,[34] saying that parliamentary socialism was "sinking in the political bog". She wrote for the IWW between 1916 and 1918. In Why I Became an IWW,[39] Keller explained that her motivation for activism came in part from her concern about blindness and other disabilities:

I was appointed on a commission to investigate the conditions of the blind. For the first time I, who had thought blindness a misfortune beyond human control, found that too much of it was traceable to wrong industrial conditions, often caused by the selfishness and greed of employers. And the social evil contributed its share. I found that poverty drove women to a life of shame that ended in blindness.

The last sentence refers to prostitution and syphilis, the former a frequent cause of the latter, and the latter a leading cause of blindness. In the same interview, Keller also cited the 1912 strike of textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts for instigating her support of socialism.

Keller supported eugenics. In 1915, she wrote in favor of refusing life-saving medical procedures to infants with severe mental impairments or physical deformities, stating that their lives were not worthwhile and they would likely become criminals.[40][41] Keller also expressed concerns about human overpopulation.[42][43]

Writings

Keller wrote a total of 12 published books and several articles.

One of her earliest pieces of writing, at age 11, was The Frost King (1891). There were allegations that this story had been plagiarized from The Frost Fairies by Margaret Canby. An investigation into the matter revealed that Keller may have experienced a case of cryptomnesia, which was that she had Canby's story read to her but forgot about it, while the memory remained in her subconscious.[28]

At age 22, Keller published her autobiography, The Story of My Life (1903), with help from Sullivan and Sullivan's husband, John Macy. It recounts the story of her life up to age 21 and was written during her time in college.

Keller wrote The World I Live In in 1908, giving readers an insight into how she felt about the world.[44] Out of the Dark, a series of essays on socialism, was published in 1913.

When Keller was young, Anne Sullivan introduced her to Phillips Brooks, who introduced her to Christianity, Keller famously saying: "I always knew He was there, but I didn't know His name!"[45][46][47]

Her spiritual autobiography, My Religion,[48] was published in 1927 and then in 1994 extensively revised and re-issued under the title Light in My Darkness. It advocates the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, the Christian theologian and mystic who gave a spiritual interpretation of the teachings of the Bible and who claimed that the Second Coming of Jesus Christ had already taken place.

Keller described the core of her belief in these words:

But in Swedenborg's teaching it [Divine Providence] is shown to be the government of God's Love and Wisdom and the creation of uses. Since His Life cannot be less in one being than another, or His Love manifested less fully in one thing than another, His Providence must needs be universal ... He has provided religion of some kind everywhere, and it does not matter to what race or creed anyone belongs if he is faithful to his ideals of right living.[48]

Overseas visits

Keller visited 35 countries from 1946 to 1957.[49]

In 1948 she went to New Zealand and visited deaf schools in Christchurch and Auckland. She met Deaf Society of Canterbury Life Member Patty Still in Christchurch.[50]

Later life

Keller suffered a series of strokes in 1961 and spent the last years of her life at her home.[28]

On September 14, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, one of the United States' two highest civilian honors. In 1965 she was elected to the National Women's Hall of Fame at the New York World's Fair.[28]

Keller devoted much of her later life to raising funds for the American Foundation for the Blind. She died in her sleep on June 1, 1968, at her home, Arcan Ridge, located in Easton, Connecticut, a few weeks short of her eighty-eighth birthday. A service was held in her honor at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., her body was cremated and her ashes were placed there next to her constant companions, Anne Sullivan and Polly Thomson. She was buried at the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C.[51]

Portrayals

Keller's life has been interpreted many times. She appeared in a silent film, Deliverance (1919), which told her story in a melodramatic, allegorical style.[52]

She was also the subject of the documentaries Helen Keller in Her Story, narrated by her friend and noted theatrical actress Katharine Cornell, and The Story of Helen Keller, part of the Famous Americans series produced by Hearst Entertainment.

The Miracle Worker is a cycle of dramatic works ultimately derived from her autobiography, The Story of My Life. The various dramas each describe the relationship between Keller and Sullivan, depicting how the teacher led her from a state of almost feral wildness into education, activism, and intellectual celebrity. The common title of the cycle echoes Mark Twain's description of Sullivan as a "miracle worker". Its first realization was the 1957 Playhouse 90 teleplay of that title by William Gibson. He adapted it for a Broadway production in 1959 and an Oscar-winning feature film in 1962, starring Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke. It was remade for television in 1979 and 2000.

In 1984, Keller's life story was made into a TV movie called The Miracle Continues.[53] This film, a semi-sequel to The Miracle Worker, recounts her college years and her early adult life. None of the early movies hint at the social activism that would become the hallmark of Keller's later life, although a Disney version produced in 2000 states in the credits that she became an activist for social equality.

The Bollywood movie Black (2005) was largely based on Keller's story, from her childhood to her graduation.[54]

A documentary called Shining Soul: Helen Keller's Spiritual Life and Legacy was produced by the Swedenborg Foundation in the same year. The film focuses on the role played by Emanuel Swedenborg's spiritual theology in her life and how it inspired Keller's triumph over her triple disabilities of blindness, deafness and a severe speech impediment.[55]

On March 6, 2008, the New England Historic Genealogical Society announced that a staff member had discovered a rare 1888 photograph showing Helen and Anne, which, although previously published, had escaped widespread attention.[56] Depicting Helen holding one of her many dolls, it is believed to be the earliest surviving photograph of Anne Sullivan Macy.[57]

Video footage showing Helen Keller learning to mimic speech sounds also exists.

A biography of Helen Keller was written by the German Jewish author Hildegard Johanna Kaeser.

A 10-by-7-foot (3.0 by 2.1 m) painting titled The Advocate: Tribute to Helen Keller was created by three artists from Kerala, India as a tribute to Helen Keller. The Painting was created in association with a non-profit organization Art d'Hope Foundation, artists groups Palette People and XakBoX Design & Art Studio.[58] This painting was created for a fundraising event to help blind students in India [59] and was inaugurated by M. G. Rajamanikyam, IAS (District Collector Ernakulam) on Helen Keller day (June 27, 2016).[60] The painting depicts the major events of Helen Keller's life and is one of the biggest paintings done based on Helen Keller's life.

Posthumous honors

A preschool for the deaf and hard of hearing in Mysore, India, was originally named after Helen Keller by its founder, K. K. Srinivasan.[61] In 1999, Keller was listed in Gallup's Most Widely Admired People of the 20th century.

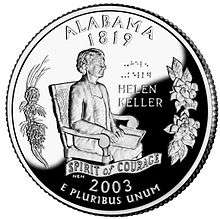

In 2003, Alabama honored its native daughter on its state quarter.[62] The Alabama state quarter is the only circulating U.S. coin to feature braille.[63]

The Helen Keller Hospital in Sheffield, Alabama, is dedicated to her.[64]

Streets are named after Helen Keller in Zürich, Switzerland, in the US, in Getafe, Spain, in Lod, Israel,[65] in Lisbon, Portugal,[66] and in Caen, France.

In 1973, Helen Keller was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[67]

A stamp was issued in 1980 by the United States Postal Service depicting Keller and Sullivan, to mark the centennial of Keller's birth.

On October 7, 2009, a bronze statue of Keller was added to the National Statuary Hall Collection, as a replacement for the State of Alabama's former 1908 statue of the education reformer Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry.[68]

Archival material

Archival material of Helen Keller stored in New York was lost when the Twin Towers were destroyed in the September 11 attacks.[69][70][71]

The Helen Keller Archives are owned by the American Foundation for the Blind.[72]

References

- "Helen Keller Birthplace". Helen Keller Birthplace Foundation, Inc.

- "Harper Lee Among Inaugural Inductees Into Alabama Writers Hall of Fame". The Huffington Post. June 8, 2015.

- "Helen Keller FAQ". Perkins School for the Blind. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- Nielsen, Kim E. (2007). "The Southern Ties of Helen Keller". Journal of Southern History. 73 (4). doi:10.2307/27649568. JSTOR 27649568.

- "Ask Keller". American Foundation for the Blind. October 2006. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- "Ask Keller". American Foundation for the Blind. November 2005. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- "Arthur H. Keller". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- "Kate Adams Keller". American Foundation for the Blind. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- Herrmann, Dorothy; Keller, Helen; Shattuck, Roger (2003). The Story of my Life: The Restored Classic. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-0-393-32568-3. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- "Ask Keller". American Foundation for the Blind. November 2005. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- "Ask Keller". American Foundation for the Blind. February 2005. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

Helen's illness was diagnosed by her doctor as "acute congestion of the stomach and the brain"

- "Helen Keller Biography". American Foundation for the Blind. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "Helen Keller's Moment". The Attic. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- Keller, Helen (1905). "The Story of My Life". New York: Doubleday, Page & Company. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- Shattuck, Roger (1904). "The World I Live In".

- Worthington, W. Curtis (March 1990). A Family Album: Men Who Made the Medical Center. Reprint Co. ISBN 978-0-87152-444-7.

- Wilkie, Katherine E. (January 1969). Helen Keller: Handicapped Girl. Atheneum. ISBN 978-0-672-50076-3.

- "Helen Keller's Moment". The Attic. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- Dahl, Hartvig. "Observation on a Natural Experiment".

- "HELEN KELLER IN COLLEGE – Blind, Dumb and Deaf Girl Now Studying at Radcliffe". Chicago Tribune: 16. October 13, 1900.

- "Phi Beta Kappa Members". The Phi Beta Kappa Society (PBK.org). Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Herbert Gantschacher "Back from History! – The correspondence of letters between the Austrian-Jewish philosopher Wilhelm Jerusalem and the American deafblind writer Helen Keller", Gebärdensache, Vienna 2009, p. 35ff.

- Specifically, the reordered alphabet known as American Braille

- "First Number Citizens Lecture Course Monday, November Fifth", The Weekly Spectrum, North Dakota Agricultural College, Volume XXXVI no. 3, November 7, 1917.

- Koser, Jessica (January 19, 2016). "From the files: New library is now open to the public". Dunn County News. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- Herrmann, Dorothy (December 15, 1999). Helen Keller: A Life. University of Chicago Press. pp. 266–. ISBN 9780226327631. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- "Tragedy to Triumph: An Adventure with Helen Keller". Graceproducts.com. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- "The life of Helen Keller". Royal National Institute of Blind People. November 20, 2008. Archived from the original on June 7, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- Sultan, Rosie (May 14, 2012). "Helen Keller's Secret Love Life". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- Herrmann, Dorothy. Helen Keller: A Life. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-32763-1.

- Nielsen, Kim. The Radical Lives of Helen Keller. NYU Press.

helen keller story.

- Helen Keller: Rebel Lives, by Helen Keller & John Davis, Ocean Press, 2003 ISBN 978-1-876175-60-3, pg 57

- McGinnity, B.L. "Helen Keller".

- Loewen, James W. (1996) [1995]. Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong (Touchstone ed.). New York, NY: Touchstone Books. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-0-684-81886-3.

- Davis, Mark J. "Examining the American peace movement prior to World War I", America Magazine, April 17, 2017

- "Wonder Woman at Massey Hall". Toronto Star Weekly. January 1914. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- George, Henry (1998). Progress & Poverty. Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. ISBN 978-0-911312-10-2.

- Keller, Helen (November 3, 1912). "How I Became a Socialist". The New York Call. Helen Keller Reference Archive. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- "Why I Became an IWW" in Helen Keller Reference Archive from An interview written by Barbara Bindley , published in the New York Tribune, January 16, 1916

- Nielsen, Kim E. (April 1, 2009). The Radical Lives of Helen Keller. New York City, NY: New York University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0814758142. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- Pernick, M S (November 1997). "Eugenics and public health in American history". American Journal of Public Health. 87 (11): 1767–1772. doi:10.2105/ajph.87.11.1767. PMC 1381159. PMID 9366633. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- "Quotes". Population Matters. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- "Quotes". World Population Balance. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- Keller, Helen (1910). The World I Live In. New York: The Century Co. ISBN 978-1-59017-067-0.

- Willmington, H. L. (1981). Willmington's Guide to the Bible. Wheaton, Illinois: Tyndale House Publishers. p. 591. ISBN 978-0-8423-8804-7. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

Sometime after she had progressed to the point that she could engage in conversation, she was told of God and his love in sending Christ to die on the cross. She is said to have responded with joy, "I always knew he was there, but I didn't know his name!"

- Helms, Harold E. (April 30, 2004). God's Final Answer. Xulon Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-59467-410-5. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

A favorite story about Helen Keller concerns her first introduction to the gospel. When Helen, who was both blind and deaf, learned to communicate, Anne Sullivan, her teacher, decided that it was time for her to hear about Jesus Christ. Anne called for Phillips Brooks, the most famous preacher in Boston. With Sullivan interpreting for him, he talked to Helen Keller about Christ. It wasn't long until a smile lighted up her face. Through her teacher she said, "Mr. Brooks, I have always known about God, but until now I didn't know His name."

- Dickinson, Mary Lowe; Avary, Myrta Lockett (1901). Heaven, Home And Happiness. The Christian Herald. p. 216. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

Phillips Brooks began to tell her about God, who God was, what he had done, how he loved me, and what he was to us. The child listened very intently. Then she looked up and said, "Mr. Brooks, I knew all that before, but I didn't know His name."

- Keller, Helen (March 17, 2007). My Religion. The Book Tree. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-1-58509-284-0.

- "Helen Keller Biography". American Foundation for the Blind (AFB.org). Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- http://deafsocietyofcanterbury.co.nz/who-we-are/history/

- Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 24973-24974). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- "Deliverance (1919)". Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- "Helen Keller: The Miracle Continues (1984) (TV)". Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- Güler, Emrah (October 28, 2013). "Helen Keller story inspires Turkish film". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- "Shining Soul: Helen Keller's Spiritual Life & Legacy". The Video Librarian. 21 (3): 86. May 1, 2006.

- "Picture of Helen Keller as a child revealed after 120 years". The Independent. London. March 7, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- "Newly Discovered Photograph Features Never Before Seen Image Of Young Helen Keller" (PDF). New England Genealogical Society. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- "A tribute to Helen Keller". The New Indian Express.

- "'Tribute to Helen Keller': Art for raising funds for blind students". www.artdhope.org. July 25, 2016.

- "Tribute to Helen Keller". The Hindu.

- "The World at your Fingertips: Helen Keller’s legacy touches deafblind children in India", Radio Netherlands Archives, February 18, 2004

- "A likeness of Helen Keller is featured on Alabama's quarter". United States Mint. March 23, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- "The Official Alabama State Quarter". The US50. March 17, 2003. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- "Helen Keller Hospital website". Helenkeller.com. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- "רחוב הלן קלר, לוד" [Helen Keller Street, Lod] (in Hebrew). Google Maps. January 1, 1970. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- "Toponomy section of the Lisbon Municipality website". Toponimia.cm-lisboa.pt. January 6, 1968. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- National Women's Hall of Fame, Helen Keller

- "Helen Keller". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved December 25, 2009.

- "Helen Keller Archive Lost in World Trade Center Attack". Poets & Writers. October 3, 2001. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- Urschel, Donna (November 2002). "Lives and Treasures Taken". Library of Congress Information Bulletin. Library of Congress. 61 (11).

- Bridge, Sarah; Stastna, Kazi (August 21, 2011). "9/11 anniversary: What was lost in the damage". CBC News. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- "Helen Keller – Our Champion". American Foundation for the Blind. 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

Bibliography

- The Frost King (1891)

- The Story of My Life (1903)

- The World I Live In (1908)

- Out of the Dark, a series of essays on socialism (1913)

- My Religion (1927, Also called "Light in my Darkness")

Further reading

| Library resources about Helen Keller |

| By Helen Keller |

|---|

- Brooks, Van Wyck. (1956) Helen Keller Sketch for a Portrait (1956)

- Harrity, Richard and Martin, Ralph G. (1962) The Three Lives of Helen Keller

- Lash, Joseph P. (1980) Helen and Teacher: The Story of Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy . New York, NY: Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0-440-03654-8

- Einhorn, Lois J. (1998) Helen Keller, Public Speaker: Sightless But Seen, Deaf But Heard (Great American Orators)

- Herrmann, Dorothy (1998) Helen Keller: A Life. New York, NY: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-44354-4

- "Keller, Helen Adams". World Encyclopedia. Philip's. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. University of Edinburgh. 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

Primary sources

- Keller, Helen with Anne Sullivan and John A. Macy (1903) The Story of My Life. New York, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co.

Historiography

- Amico, Eleanor B., ed. Reader's Guide to Women's Studies (Fitzroy Dearborn, 1998) pp328–29

External links

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Helen Keller International

- Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Archive at Perkins School for the Blind

- Works by Helen Keller at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Helen Keller at Internet Archive

- Works by Helen Keller at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Helen Keller at Women Film Pioneers Project

- Helen Keller on IMDb

- Helen Keller at the TCM Movie Database

- FBI Records: The Vault – Helen Keller at fbi.gov

- Helen Keller at the American Film Institute Catalog

- The Story of My Life with introduction to the text

- Philip Foner, Helen Keller, Her Socialist Years: Writings and Speeches. New York: International Publishers, 1967.

- "Who Stole Helen Keller?" by Ruth Shagoury in the Huffington Post, June 22, 2012.

- Papers of Helen Adams Keller, 1898–2003 Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Poems by Florence Earle Coates: "To Helen Keller", "Helen Keller with a Rose", "Against the Gate of Life"

- Michals, Debra. "Helen Keller". National Women's History Museum. 2015.

- Newspaper clippings about Helen Keller in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Finding aid to Adele C. Brockhoff letters, including Keller correspondence, at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.