Fort Bridger

Fort Bridger was originally a 19th-century fur trading outpost established in 1842, on Blacks Fork of the Green River, in what is now Uinta County, Wyoming, United States. It became a vital resupply point for wagon trains on the Oregon Trail, California Trail, and Mormon Trail. The Army established a military post here in 1858 during the Utah War, until it was finally closed in 1890. A small town, Fort Bridger, Wyoming, remains near the fort and takes its name from it.

Fort Bridger | |

Fort Bridger | |

Fort Bridger Site of fort in Wyoming  Fort Bridger Fort Bridger (the United States) | |

| Location | Uinta County, Wyoming, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Fort Bridger, Wyoming |

| Coordinates | 41°19′4″N 110°23′31″W |

| NRHP reference No. | 69000197 |

| Added to NRHP | 1969-04-16 |

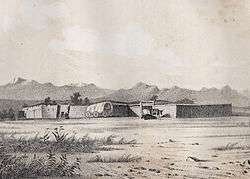

Bridger's Trading Post

The post was established by the mountain man Jim Bridger, after whom it is named, and Louis Vasquez.[1] Bridger, perhaps the most picturesque figure in early Wyoming, was often called the "Daniel Boone" of the Rockies. Bridger’s Pass, which he discovered, was also named for him.[2]

In 1845, Lansford Hastings published a guide entitled The Emigrant's Guide to Oregon and California, which advised California emigrants to leave the Oregon Trail at Fort Bridger, pass through the Wasatch Range across the Great Salt Lake Desert (an 80-mile waterless drive), loop around the Ruby Mountains, and rejoin the California Trail about seven miles west of modern Elko, Nevada (now Emigrant Pass). The ill-fated Donner-Reed Party followed that route, along which they were met by a rider sent by Hastings to deliver letters to traveling emigrants. On July 12, the Donners and Reeds were given one of these letters,[3] in which among other messages, Hastings claimed to have "worked out a new and better road to California", and said he would be waiting at Fort Bridger to guide the emigrants along the new cutoff.[4]

Mormons and Fort Supply

With the arrival of the Mormon pioneers in 1847, disputes arose between Bridger and the new settlers. By 1853, a militia of Mormons was sent to arrest him for selling alcohol and firearms to the Native Americans, a violation of Federal Law.[5] He escaped capture and temporarily returned to the East. Near the existing fort, the Mormons established their own Fort Supply the same year. In 1855, Mormons took over Fort Bridger, reportedly having bought it for $8,000 in gold coins.[6] The Mormons claimed, over Bridger's denials, they had purchased the fort from Vasquez. There was a deed dated August 3, 1855, recorded October 21, 1858, in Salt Lake City in Records Book B. p. 128, that ostensibly sold Fort Bridger to the LDS Church. Bridger and Vasquez's names were signed by H.F. Morrell in the presence of Alinerin Grow and William Adams Hickman, purportedly pursuant to a power of attorney. Bridger was absent from the area in 1855, acting as guide for Sir St George Gore.[7]

Utah War

Relations deteriorated between Mormon leaders in Utah Territory and federal authorities in Washington, D.C. Following the election of President James Buchanan, the United States Army was ordered to Utah to install a new governor, replacing Brigham Young, as well as to establish a military presence. As the army advanced, the Mormons in the Green River valley withdrew, burning Fort Supply and Supply City. On the night of October 7, 1857, "Wild Bill" Hickman set fire to Fort Bridger to keep it from falling into the hands of the approaching United States Army during the Utah War.

The army wintered near Fort Bridger. In June 1858, as the majority of Johnston's Army set off for Salt Lake City, two companies of troops remained behind and established Fort Bridger as an official Army post. The other troops continued on and eventually established Camp Floyd south of Salt Lake City.[8]

In 1858, William A. Carter was appointed as post sutler at Fort Bridger. Perhaps more than any other individual, the history of the post revolves around this civilian merchant who remained at the center of the post's activities for its entire history.

At the end of the hostilities, the United States Congress rejected Brigham Young's claim to the fort and did not recognize Jim Bridger's continuing claims to the fort.

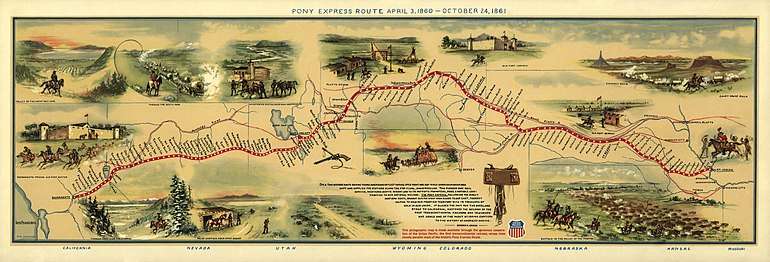

Fort Bridger as Pony Express Station

The historical Fort Bridger has several interesting old buildings still standing: the old Pony Express barn and the Mormon protective wall.[9]

Civil War

Following the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, all the federal troops in Utah Territory were withdrawn to fight the Confederate States Army in the east. The following year, Colonel Patrick Edward Connor was sent to Utah with a column of California Volunteer Cavalry and Infantry, establishing Fort Douglas near Salt Lake City. Connor later sent two companies and reestablished Army presence at Fort Bridger. A variety of volunteer units were stationed at Bridger during the Civil War.

Return of the Regular Army

In 1866, with the muster out of the volunteer units, the Regular Army returned to man Fort Bridger, beginning with companies of the Eighteenth Infantry. The post became somewhat less isolated in 1869, when the Union Pacific Railroad was built through the area.

Ultimately, the expansion of the railroads in the west made this and other forts obsolete. Fort Bridger was first abandoned in 1878 but then was re-established two years later. The Army closed the post in 1890 when Wyoming became a state.[10]

Town of Fort Bridger

After the Army's departure the buildings were sold off, and the site soon became a cattle town in southwest Wyoming. A hotel was established in the old Commanding Officer's Quarters, and the large stone barracks eventually became a milking barn.

Fort Bridger State Historic Site

In 1928, Fort Bridger was sold to the Wyoming Historic Landmark Commission for preservation as an historic monument, now designated as Fort Bridger State Historic Site. Several original buildings remain and have been restored. For example, the 1888 stone barracks contains a museum with artifacts from different time periods in the fort's history, and visitors can tour the reconstructed trading post and an interpretive archaeological site.

Annual fur trade rendezvous at Fort Bridger

The Fort Bridger Rendezvous is a celebration of the 19th century fur trade era. The event, also known as the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous at Fort Bridger, has been an annual event since the mid-1970s. It is now one of the largest rendezvous in the west, drawing hundreds of merchants and several thousand visitors each year. The rendezvous is run by the Fort Bridger Rendezvous Association, a non-profit organization. Events include primitive demonstrations, cook-offs, black powder rifle shooting, knife throwing and hawk contests, candy cannons, Native American Indian dancing, storytelling, magic shows, and more. A large portion of the rendezvous is commerce. All products sold within the fort during the rendezvous must pre-date or be a replica of something that pre-dates 1840.

Photographers at Fort Bridger

Photographers had been passing through this frontier military post since almost the inception of the art form. Daguerreotypist John Wesley Jones visited the garrison in 1851, and Samuel C. Mills, traveling with the Army bound for Utah, produced at least one image of Fort Bridger in 1858. Salt Lake City photographer Charles W. Carter came during the winter of 1866-67, and his former mentor, Charles Savage, visited a number of times between 1866 and the early 1870s. The noted Union Pacific Railroad photographer Andrew J. Russell also stopped here in 1869. Census records show a photographer named Simeon Pierson at the post in 1870. In 1876-77, a soldier, Private Charles Howard, ran a studio at the post.

Archaeology

Dr. Dudley Gardner began work at Fort Bridger in 1990. He and his students have uncovered a portion of Bridger's original post, the Mormon fortification, and the Army's subsequent occupation. Work is currently advancing on the official excavation reports.

References

- Alter, J. Cecil (1962). Jim Bridger. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Godfrey, Anthony (August 1994). Pony Express National Historic Trail Historic Resource Study. National Park Service.

- Johnson, pp. 6–7.

- Andrews, Thomas F. (April 1973). "Lansford W. Hastings and the Promotion of the Great Salt Lake Cutoff: A Reappraisal". The Western Historical Quarterly. 4 (2): 133–150. doi:10.2307/967168.

- "Fort Bridger, Wyoming State Historic Site". Legendsofamerica.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- Gowans, Fred R. & Campbell, Eugene E. (1976). Fort Supply: Brigham Young's Green River Experiment. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Fort Bridger Photos". Wyomingtalesandtrails.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- Ellison, R. S. (1931). Fort Bridger: A Brief History.

- Godfrey, Anthony (August 1994). Pony Express National Historic Trail Historic Resource Study. National Park Service.

- "About - Fort Bridger State Historic Site". Wyoming Division of State Parks and Historic Sites. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Bridger. |

- Fort Bridger page, Wyoming Department of State Parks and Historic Sites

- Fort Bridger info from the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office

- Fort Bridger - Legends of America information

- fortbridgerrendezvous.net - Additional information about the Fort Bridger Rendezvous.