Great Falls, Montana

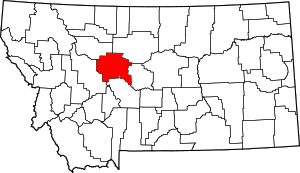

Great Falls is a city and the county seat of Cascade County, Montana, United States.[5] The 2019 census estimate put the population at 58,434.[6] The population was 58,505 at the 2010 census. It is the principal city of the Great Falls, Montana Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of Cascade County and has a population of 82,278.[7] Great Falls was the largest city in Montana from 1950 to 1970, when Billings surpassed it. Great Falls remained the second largest city in Montana until 2000, when it was passed by Missoula.[8] Since then Great Falls has been the third largest city in the state.[9]

Great Falls | |

|---|---|

City and County seat | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Electric City | |

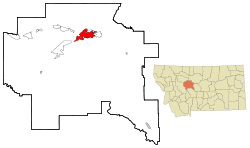

Location within Cascade County and Montana | |

Great Falls, Montana Location in the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 47°30′13″N 111°17′11″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana |

| County | Cascade |

| Incorporated | 1888 |

| Named for | Great Falls of the Missouri River |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bob Kelly |

| Area | |

| • City and County seat | 23.45 sq mi (60.74 km2) |

| • Land | 22.97 sq mi (59.50 km2) |

| • Water | 0.48 sq mi (1.24 km2) |

| Elevation | 3,330 ft (1,010 m) |

| Population | |

| • City and County seat | 58,505 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 58,434 |

| • Rank | US: 617th |

| • Density | 2,543.59/sq mi (982.09/km2) |

| • Metro | 82,278 (US: 374th) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 59401-59406 |

| Area code | 406 |

| FIPS code | 30-32800 |

| Website | greatfallsmt.net |

Great Falls takes its name from the series of five waterfalls in close proximity along the upper Missouri River basin that the Lewis and Clark Expedition had to portage around over a ten-mile stretch; the effort required 31 days of arduous labor during the westward leg of their 1805–06 exploration of the Louisiana Purchase and to the Pacific Northwest Coast of the Oregon Country. Each falls sports a hydroelectric dam today, hence Great Falls is nicknamed "the Electric City". Currently there are two undeveloped parts of their portage route; these are included within the Great Falls Portage, a National Historic Landmark.

The city is home to the C. M. Russell Museum Complex, the University of Providence, Great Falls College Montana State University, Apollos University, Giant Springs, the Roe River (which is claimed to be the world's shortest river), the Montana School for the Deaf and the Blind, the Great Falls Voyagers minor league baseball team, and is adjacent to Malmstrom Air Force Base. The local newspaper is the Great Falls Tribune.

History

The first human beings to live in the Great Falls area were Native Americans. The area remained only sparsely inhabited.[10] Salish Indians would seasonally hunt bison in the region but no permanent settlements existed at or near Great Falls for much of prehistory.[10] Around 1600, Piegan Blackfeet Indians, migrating west, entered the area, pushing the Salish back into the Rocky Mountains and claiming the site now known as Great Falls.[10] The area remained the territory of the Blackfeet until long after the United States claimed the region in 1803 in the Louisiana Purchase.[11][12]

Meriwether Lewis was the first white person to visit the area, which he did on June 13, 1805, as part of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.[13][14] York, an enslaved African owned by William Clark and who had participated in the Expedition, was the first black American to visit the site.[15]

Following the return passage of Lewis and Clark in 1806,[16] there is no record of any white person visiting the site of the city of Great Falls until explorer and trapper Jim Bridger reached the area in 1822.[11] Bridger and Major Andrew Henry led a fur-trading expedition to the future city location in April 1823 (and were attacked by Blackfeet Indians while camping at the site).[17] British explorer Alexander Ross trapped around Great Falls in 1824.[18] In 1838, a mapping expedition sent by the U.S. federal government and guided by Bridger spent four years in the area.[11] Margaret Harkness Woodman became the first white woman to visit the Great Falls area in 1862.[19]

The Great Falls of the Missouri River marked the limit of the navigable section of the Missouri River for non-portagable watercraft,[20] and the non-navigability of the falls was noted by the U.S. Supreme Court in its 2012 ruling against the State of Montana on the question of streambed ownership beneath several dams situated at the site of the falls.[21] The first steamboat arrived at future site of the city in 1859.[22]

Politically, the future site of Great Falls passed through numerous hands in the 19th century. It was part of the unincorporated frontier until May 30, 1854, when Congress established the Nebraska Territory.[23] Indian attacks on white explorers and settlers dropped significantly after Isaac Stevens negotiated the Treaty of Hellgate in 1855, and white settlement in the area began to occur.[11] On March 2, 1861, the site became part of the Dakota Territory.[24] The Great Falls area was incorporated into the Idaho Territory on March 4, 1863,[25] and then into the Montana Territory on May 28, 1864.[10] It became part of the state of Montana upon that territory's admission to statehood on November 8, 1889.[10]

Founding and industrial significance

Great Falls was founded in 1883. Businessman Paris Gibson visited the Great Falls of the Missouri River in 1880, and was deeply impressed by the possibilities for building a major industrial city near the falls with power provided by hydroelectricity.[26][27][28][29] He returned in 1883 with friend Robert Vaughn and some surveyors and platted a permanent settlement the south side of the river.[11][26][27] The city's first citizen, Silas Beachley, arrived later that year.[11] With investments from railroad owner James J. Hill and Helena businessman Charles Arthur Broadwater, houses, a store, and a flour mill were established in 1884.[11][26][27][28][29] The Great Falls post office was established on July 10, 1884, and Paris Gibson was named the first postmaster.[30] A planing mill, lumber yard, bank, school, and newspaper were established in 1885.[26][29] By 1887 the town had 1,200 citizens, and in October of that year the Great Northern Railway arrived in the city.[26][28][29] Great Falls was incorporated on November 28, 1888.

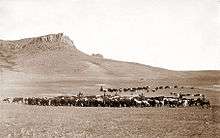

Great Falls quickly became a thriving industrial and supply center. In 1894, naturalist Vernon Bailey passed through and described Great Falls as "a very good town, appears prosperous and booming & I should judge contains 15000 inhabitants."[31] By the early 1900s, Great Falls was en route to becoming one of Montana's largest cities. The rustic studio of famed Western artist Charles Marion Russell was a popular attraction, as were the famed "Great Falls of the Missouri", after which the city was named.

Railroad and hydro power expansion

James Jerome Hill, primary stockholder and president of the Great Northern Railway (U.S.) had established a subsidiary, the Montana Central Railway, on January 25, 1886. The mines in Butte were eager to get its metals to market. Gold and silver had been discovered near Helena, and coal companies in Canada were eager to get their fuel to Montana's smelters. Hill's close friend and business associate, Paris Gibson, was promoting Great Falls as a site for the development of cheap hydroelectricity and heavy industry. Hill was building the Great Northern across the northern tier of Montana, and it made sense to build a north–south railroad through central Montana to connect Great Falls with Helena and Butte. Surveyors and engineers had begun grading a route between Helena and Great Falls in the winter of 1885–1886, and by the end of 1886 had surveyed a route from Helena to Butte. Construction on the Great Northern's line westward began in late 1886, and on October 16, 1887, the link between Devils Lake, North Dakota; Fort Assinniboine (near the present-day city of Havre); and Great Falls was complete. Service to Helena began in November 1887, and Butte followed on November 10, 1888.

Hill organized the Great Falls Water Power & Townsite Company in 1887, with the goal of developing the town of Great Falls; providing it with power, sewage, and water; and attracting commerce and industry to the city. To attract industry to the new city, he offered low rates on the Montana Central Railway. On September 12, 1889, the Boston and Montana ("B & M") signed an agreement with Great Falls Water Power & Townsite Company in which the power company agreed to build a dam that would supply the mining firm with at least 1,000 horsepower (or 0.75 MW) of power by September 1, 1890, and 5,000 horsepower (or 3.73 MW) of power by January 1, 1891. In exchange, B & M agreed to build a $300,000 copper smelter near the dam. Black Eagle Dam began generating electricity in December 1890. Water was permitted to flow over the crest of the dam on January 6, 1891, and the dam was considered complete on March 15, 1891. By 1912 Rainbow Dam and Volta Dam (now Ryan Dam) were all operating.[11][26][29] Morony Dam was built in 1930 and Cochrane Dam in 1957–58.

Smelting operations

On April 7, 1908, construction began on a masonry/brick chimney measuring 506 feet (154 m) tall on the B & M's – now the city's largest employer – smelting site at Black Eagle, Montana, by the Alphonse Custodis Construction Co. of New York, for dispersal of fumes from B & M's copper smelting process. The B & M would soon merge with the Amalgamated Copper Company and become the Anaconda Copper Mining Company or "ACM". The B & M smelter stack was completed in on October 23, 1908. The chimney had an interior measurement of 78.5 feet (23.9 m) in diameter at the base and 50 feet (15 m) in diameter at the top. At the time of its completion it was the tallest chimney in the world (see List of tallest chimneys). With the moniker "The Big Stack", it immediately became a landmark for the community, but after over 70 years of operation the smelter closed in 1980.

The Big Stack's 'sister' stack in Anaconda, also of masonry/brick construction, completed in 1919, and slightly taller at 585 feet (178 m), was beginning to suffer from cracking and the ACM decided to remove the support bands from the upper half of the Big Stack in 1976 and send them to Anaconda. This action proved to be the Big Stack's ultimate demise since the cracks it was also suffering from rapidly worsened such that the ACM, citing concern for public safety (due to the stack's continual deterioration of its structural integrity), slated the Big Stack's demolition for September 18, 1982. In an interesting twist of fate the demolition crew failed to accomplish the task on the first try; the two worst cracks in the stack ran from just above ground level to nearly 300 feet up. The demolition team's intent was to create a wedge in the base so the stack's rubble would fall almost vertically into a large trench, but as the 600 lbs of explosives were set off the cracks 'completed themselves' all the way to the ground—effectively severing the stack into two-thirds and one-third pieces. Much to the delight of the spectating community, the smaller of the two pieces remained standing, but the failed demolition only solidified the safety issue whereas the community cited the event as the stack's defiance. The demolition team who had planted the charges was recalled and later the same afternoon they returned and finished the demolition, after packing another 400 lbs of explosives into the smaller wedge.

During World War II the Northwest Staging Route passed through the city on which planes were delivered to the USSR according to the Lend-Lease program. Great Falls prospered further with the opening of a nearby military base in the 1940s, but as rail transportation and freight slowed in the later part of the century, outlying farming areas lost population, and with the closure of the smelter and cutbacks at Malmstrom Air Force Base in the 1980s, its population growth slowed.

The economy of Great Falls has suffered from the decline of heartland industry in recent years much like other cities in the Great Plains and Midwest.

Geography

Great Falls is located near several waterfalls on the Missouri River. It lies near the center of Montana on the northern Great Plains. It lies next to the Rocky Mountain Front and is about 100 miles (160 km) south of the Canada–US border. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 22.26 square miles (57.65 km2), of which, 21.79 square miles (56.44 km2) is land and 0.47 square miles (1.22 km2) is water.[32]

Geology

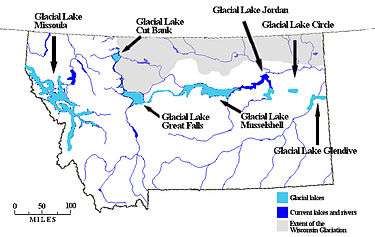

The city of Great Falls lies atop the Great Falls Tectonic Zone, an intracontinental shear zone between two geologic provinces of basement rock of the Archean period which form part of the North American continent.[33] The city lies at the southern reach of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, a vast glacial sheet of ice which covered much of North America during the last glacial period. Approximately 1.5 million years ago, the Missouri River flowed northward into a terminal lake.[34][35] The Laurentide Ice Sheet pushed the river southward.[34][36] Between 15,000 BCE and 11,000 BCE, the Laurentide Ice Sheet blocked the Missouri River and created Glacial Lake Great Falls.[37][36][38] About 13,000 BCE, as the glacier retreated, Glacial Lake Great Falls emptied catastrophically in a glacial lake outburst flood.[37] The current course of the Missouri River essentially marks the southern boundary of the Laurentide Ice Sheet.[39] The Missouri River flowed eastward around the glacial mass, settling into its present course.[34] As the ice retreated, meltwater from Glacial Lake Great Falls poured through the Highwood Mountains and eroded the mile-long, 500-foot-deep (150 m) Shonkin Sag, one of the most famous prehistoric meltwater channels in the world.[40]

Climate

Great Falls has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSk),[41] with a notable amount of summer precipitation occurring in the form of thunderstorms. Winters are very cold, long and often snowy, though periods of chinook winds do cause warm spells and raise the maximum temperature above 50 °F or 10 °C on an average of fifteen afternoons during the three-month winter period.[42] In the absence of such winds, shallow cold snaps are common; there is an average of 20.8 nights with a low of 0 °F (−17.8 °C) or colder and 44 days failing to top freezing. The wettest part of the year is the spring. Summers are hot and dry, with highs reaching 90 °F (32.2 °C) on nineteen days per year, though the diurnal temperature variation is large and easily exceeds 30 °F (16.7 °C).[43] Freak early and late summer snowfalls such as a two-day total of 8.3 in (0.21 m) in August 1992 can occur, although the median snowfall from June to September is zero and on average the window for accumulating (0.1 in or 0.25 cm) snowfall is October 2–May 13.[43] The average first and last freeze dates are September 21 and May 21, respectively, allowing a growing season of 122 days, although, excepting for July, a freeze has occurred in every month of the year. Extreme temperatures range from −49 °F (−45.0 °C) on February 15, 1936 to 107 °F (41.7 °C) on July 25, 1933.

| Climate data for Great Falls, Montana (Great Falls Int'l), 1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1891–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

70 (21) |

78 (26) |

89 (32) |

100 (38) |

102 (39) |

107 (42) |

106 (41) |

98 (37) |

91 (33) |

76 (24) |

69 (21) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57.4 (14.1) |

59.1 (15.1) |

66.5 (19.2) |

76.3 (24.6) |

83.6 (28.7) |

90.8 (32.7) |

97.3 (36.3) |

96.5 (35.8) |

89.0 (31.7) |

79.2 (26.2) |

64.9 (18.3) |

54.5 (12.5) |

98.9 (37.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 35.5 (1.9) |

38.3 (3.5) |

45.9 (7.7) |

55.6 (13.1) |

64.8 (18.2) |

73.3 (22.9) |

83.4 (28.6) |

82.3 (27.9) |

70.3 (21.3) |

57.7 (14.3) |

43.3 (6.3) |

34.6 (1.4) |

57.2 (14.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 14.9 (−9.5) |

16.4 (−8.7) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

38.6 (3.7) |

46.1 (7.8) |

51.4 (10.8) |

50.4 (10.2) |

42.0 (5.6) |

32.8 (0.4) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

32.1 (0.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −13.9 (−25.5) |

−10.8 (−23.8) |

0.8 (−17.3) |

14.8 (−9.6) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

36.1 (2.3) |

42.6 (5.9) |

40.4 (4.7) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

13.2 (−10.4) |

−2.4 (−19.1) |

−13.7 (−25.4) |

−25.0 (−31.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −44 (−42) |

−49 (−45) |

−32 (−36) |

−10 (−23) |

12 (−11) |

31 (−1) |

35 (2) |

30 (−1) |

10 (−12) |

−11 (−24) |

−25 (−32) |

−43 (−42) |

−49 (−45) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.51 (13) |

0.47 (12) |

0.91 (23) |

1.42 (36) |

2.42 (61) |

2.53 (64) |

1.50 (38) |

1.57 (40) |

1.42 (36) |

0.86 (22) |

0.59 (15) |

0.55 (14) |

14.75 (374) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.6 (22) |

8.2 (21) |

11.9 (30) |

8.6 (22) |

2.7 (6.9) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

1.2 (3.0) |

4.1 (10) |

8.1 (21) |

9.5 (24) |

63.5 (161.42) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.8 | 7.0 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 99.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 7.2 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 4.5 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 45.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 125.1 | 151.7 | 237.5 | 245.7 | 286.6 | 316.5 | 377.4 | 330.8 | 254.4 | 200.4 | 124.8 | 105.4 | 2,756.3 |

| Source: NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[44][45] | |||||||||||||

Suburbs of Great Falls

Census-designated places contiguous to the City of Great Falls include:

Nearby communities

The entirety of Cascade County, is the Great Falls Metropolitan statistical area. Great Falls is an economic hub for a substantially larger region that includes most of north-central Montana. Small towns and census-designated places in Cascade County near Great Falls include:

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 3,979 | — | |

| 1900 | 14,930 | 275.2% | |

| 1910 | 13,948 | −6.6% | |

| 1920 | 24,121 | 72.9% | |

| 1930 | 28,822 | 19.5% | |

| 1940 | 29,928 | 3.8% | |

| 1950 | 39,214 | 31.0% | |

| 1960 | 55,244 | 40.9% | |

| 1970 | 60,091 | 8.8% | |

| 1980 | 56,725 | −5.6% | |

| 1990 | 55,097 | −2.9% | |

| 2000 | 56,690 | 2.9% | |

| 2010 | 58,505 | 3.2% | |

| Est. 2019 | 58,434 | [4] | −0.1% |

| source:[46] U.S. Decennial Census[47] 2018 Estimate[48] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 58,505 people, 25,301 households, and 15,135 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,684.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,036.6/km2). There were 26,854 housing units at an average density of 1,232.4 per square mile (475.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.5% Caucasian, 1.1% African American, 5.0% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.6% from other races, and 3.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 3.4% of the population.

There were 25,301 households of which 28.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.6% were married couples living together, 11.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.8% had a male householder with no wife present, and 40.2% were non-families. 33.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.88.

The median age in the city was 39 years. 22.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.5% were from 25 to 44; 26.5% were from 45 to 64; and 16.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.9% male and 51.1% female.

2000 census

As of the 2000 census, there were 56,690 people, 23,834 households, and 14,848 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,909.1 people per square mile (1,123.0/km2). There were 25,250 housing units at an average density of 1,295.7 per square mile (500.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.96% caucasian, 0.95% African American, 5.09% Native American, 0.86% Asian, 0.09% Pacific Islander, 0.60% from other races, and 2.45% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 2.39% of the population.

There were 23,834 households out of which 30.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.4% were married couples living together, 11.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.7% were non-families. 31.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 24.9% under the age of 18, 9.0% from 18 to 24, 27.7% from 25 to 44, 22.7% from 45 to 64, and 15.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $32,436, and the median income for a family was $40,107. Males had a median income of $29,353 versus $20,859 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,059. About 11.1% of families and 14.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.3% of those under the age of 18 and 9.2% of those 65 and older.

Economy

Historic economy

Built as a railroad hub, Great Falls initially relied heavily on ore smelting in its early years.[49] Black Eagle Dam, opened in 1890,[50] was the first hydroelectric dam built in Montana[51][52][53] and the first built on the Missouri River.[50] The energy industry helped give the city of Great Falls the nickname "The Electric City."[54] The same year, the Boston and Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Company broke ground on a large smelter in the city,[55] drawn to the location by the power provided by the dam.[56] Elements came online over the next few years, with the final works—an electrolytic refinery and blast furnaces—completed in February and April 1893.[55][57] By 1892, more than 1,000 workers were employed at the smelter.[58] Energy production received a boost with the discovery of petroleum about 100 miles (160 km) north of the city in the late 1910s. Great Falls boasted two oil refineries by 1920, although a devastating fire left the city with just one after 1929.[59]

Great Falls suffered its first major economic crisis in 1893. Banks and industry in the city were severely undercapitalized, and the Panic of 1893 cut off access to money in the east. The price of silver collapsed and nearby mines closed. Markets for beef, mutton, and wool largely disappeared, leaving area ranchers destitute. A large number of businesses in Great Falls shut their doors. The city was largely saved by the smelter, which continued to employ about 900 workers from 1895 to 1900. A North Montana Agricultural Society was formed to bring improvements in the practice of cattle ranching and wheat farming, and to lobby for federal- and state-funded irrigation projects.[60][61] An attempt to win state legislative approval for an official state fair to be located at Great Falls failed in 1894, but organizers were successful in holding the first Cascade County Fair in May 1895.[60][62]

The city became even more prominent as an agricultural products center.[63][64] Wheat production began to soar in Montana during the 1906-1907 growing season,[65] and by 1920 there were 11 railroad spur lines radiating from the city to collect the grain from local farmers.[63] The city's easy access to inexpensive electrical power made it ideal for grain milling and meat refrigeration, and enabled Great Falls to become a major center for farmers and ranchers.[56] The Royal Milling Company was founded in Great Falls in 1892, and within seven years was making half the flour in the state.[66] It tripled its capacity to 10,500 US bushels (370,000 l; 84,000 US dry gal; 81,000 imp gal) per day in 1917,[67] then in 1928 merged with about 25 other mills nationwide to form General Mills.[68] Montana Flour Mills opened its Great Falls facility in 1916,[66] and had a capacity of 4,500 US bushels (160,000 l; 36,000 US dry gal; 35,000 imp gal) per day in 1920.[65] Royal had a regional grain storage capacity in 1920 of more than 1,500,000 US bushels (53,000,000 l; 12,000,000 US dry gal; 12,000,000 imp gal), while Montana Flour's approached 2,250,000 US bushels (79,000,000 l; 18,000,000 US dry gal; 17,400,000 imp gal).[65] Brewing became a major industry in the city,[49] with the 1892 Montana Brewing Company (makers of Great Falls Select beer) leading the way.[69] The city's close proximity to Montana's cattle-rich Judith Basin also led to the development of a large meat packing industry. Led by the Great Falls Meat Co., Needham Packing Company, Stafford Meat Co., Valley Meat Market, and other slaughterhouses, Great Falls was the largest meat packing center between Spokane, Washington, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, by the 1930s.[70]

The city's population boomed, reaching 30,000 by 1913.[49] The 145-bed Columbus Hospital (a Catholic Church-owned facility) opened in 1892 and the 330-bed Montana Deaconess Medical Center (originally a Methodist Episcopal Church facility) opened in 1898,[71] making the city a destination for those with serious healthcare needs for central Montana. During the 1910s, Great Falls became known as a regional banking city,[72] with three national- and three state-chartered banks (although just two national and one state bank would survive the Great Depression).[73] Large regional deposits of clay, coal, gypsum, limestone, and sandstone led to the emergence of large brick works, cement works, plaster works, and stone cutting facilities in the town.[49][lower-alpha 2]

A major drought hit the counties north of the Missouri River in 1917, and spread to the rest of the state in 1918. Massive swarms of locusts struck the state in 1919, and in 1920 strong, steady winds eroded the topsoil, damaging the productivity of the soil and creating a "dust bowl" effect.[75][lower-alpha 3] Montana farmers were therefore largely unable to take advantage of the high price of wheat and other agricultural products created by wartime demand and the loss of agricultural output in Europe caused by World War I.[76] The drought did not end: Just six of the 13 years from 1917 to 1930 saw average or above-average precipitation in the state.[77] As agricultural production in Europe recovered after 1920, war-inflated agricultural prices collapsed.[76][lower-alpha 4] The high costs associated with the Great Falls-area underground coal mines led to the collapse of this local industry in the 1920s as well, devastating Great Falls coal dealers and shippers.[78] Although the post–World War I recession lifted nationally by 1922, the economy of Great Falls and the rest of the state remained mired in depression until the mid-1920s.[76][79]

The city's economy stagnated during the Great Depression.[56] The price of copper fell by nearly 75 percent to just 5 cents a pound between 1929 and 1933.[80] Anaconda cut production in the state by 75 percent and closed its plant in Great Falls,[81] throwing hundreds out of work. Agricultural prices, too, collapses. Half of the state's farmers lost their land to foreclosure,[82][83] and 60,000 of the 80,000 homesteaders who had arrived between 1900 and 1917 left the state.[84] By the time the Great Depression ended in 1940, 11,000 farms (20 percent of the state's total) had been abandoned and 2,000,000 acres (810,000 ha) of farmland had gone out of cultivation.[83] Even as the national population grew by 16 percent between 1930 and 1940, Montana's population declined.[83] Great Falls was one of the rare places in Montana which saw population growth. The city grew from 28,822 residents in 1930 to 29,928 residents in 1940.[85]

World War II saw the establishment of East Base (now Malmstrom Air Force Base) in Great Falls in 1941, proved to be a turning point economically.[86] The war not only created a huge demand for the agricultural products and metal products provided by the city but also fueled significant population growth in Great Falls. The base brought 4,000 new residents to the city;[86] by 1943, the city's population had shot up by about 5,600 to 35,000. These new residents created a huge demand for goods and services, and a large number of new businesses sprang up to supply the base with its needs. The rapid population growth created a housing construction boom in Great Falls. The federal government paid for the construction of 300 new single-family homes during the war,[87] although this was nowhere near the amount of new housing needed.[88] East Base created a fundamental cultural and social shift in the city,[86] one which became more pronounced over time as active-duty personnel stayed in the city after retirement.[56] The war also saw a major improvement to the Great Falls Municipal Airport. The 1928[89] facility received its first air traffic control tower in 1942, paid for by the federal government after the vast increase in flights over the city after the construction of the new air base.[90]

By 1950, Great Falls was Montana's largest city,[91] having added 33 percent more residents during the 1940s.[92] Much of the city's growth was due to rising federal investment in defense and healthcare,[93] and it was an important regional convention, trade, and medical center.[94] In 1951, Anaconda consolidated its statewide zinc production in Great Falls, adding substantial numbers of new workers,[95] and in 1955 opened an aluminum smelter in the city.[96] The O.S. Warden Bridge opened in 1951.[97] Designed to turn a then-mostly undeveloped 10th Avenue S. into a straight-line bypass through the city,[98][lower-alpha 5] Extraordinary increases in traffic on 10th Avenue S. led the state to transform the two-lane street in 1956 into an 80-foot (24 m) wide four-lane highway with a central median.[98][lower-alpha 6] Previously an undeveloped area with only the occasional residence,[101] the 1956 changes to 10th Avenue S. turned the highway into a vibrant business district.[102] Construction of the new campus of the College of Great Falls began on 10th Avenue S. in 1959,[lower-alpha 7] and the new Deaconess Hospital in 1963.[104] 10th Avenue S. received its first traffic signals in 1964.[98]

Great Falls' reputation as a retail hub for central Montana emerged in the 1960s. The Holiday Village Mall opened as an open-air shopping center in 1959,[105] and by 1969 had expanded to become a modern enclosed shopping mall.[106] Westgate Mall opened in 1965,[107] Agri-Village Warehouse (later Agri-Village Shopping Center) in 1967,[108] and Evergreen Mall in 1983.[109] The city was one of Montana's most important agricultural equipment sales and distribution hubs,[110] and the Great Falls Livestock Commission Company (established in 1936)[111] had become an important multistate livestock auction center.[110]

In the 1960s, Great Falls' economic future appeared bright. The city's population reached 55,357 in 1960, an 85 percent increase since 1940.[112] It was one of the fastest-growing cities in the nation.[92] Including the adjacent unincorporated town of Black Eagle, Malmstrom Air Force Base personnel, and certain minor adjacent residential blocks, the population was estimated to be more than 72,000 by 1964.[113] The largest city in Montana in 1965,[99] state planning agencies believed Great Falls would have a population of 100,000 by 1981.[114]

The economy of Great Falls began a significant diminution in the 1970s. The nation of Chile nationalized Anaconda Copper's extensive, lucrative copper mines in 1971, causing the company to suffer massive financial losses. It closed its Great Falls zinc operation in 1971,[96] and the rest of the smelter in 1980.[115] About 1,450 high-wage Anaconda employees lost their jobs during the decade.[116] Changes in the defense posture of the United States led to significant cutbacks at Malmstrom Air Force Base as well. These included the loss of 476 airmen and officers in 1972,[117][lower-alpha 8] 30 airmen in 1974,[123] 1,015 airmen and officers in 1979,[124] 100 airmen in 1981,[125] 30 airmen in 1982,[126] and 360 airmen and officers in 1983.[127] The job losses stripped $18.2 million from the local economy in 1985 alone.[128] The base lost another 1,017 jobs between 1992 and 1996.[129]

Current economy

Since the Great Recession of 2008–2010, the Great Falls economy proved sluggish, growing at an annual rate of 0.9 percent, compared to a statewide average of 1.8 percent and a national rate of 2.0 percent.[130] Growth was strongest in construction and manufacturing,[131] followed by back-office business services (such as Blue Cross Blue Shield of Montana's new insurance claims processing center), healthcare (such as the opening of the Great Falls Clinic Hospital), retail sales, social welfare (such as the opening of the Cameron Family Center, which houses 26 homeless families), and tourism.[132] The city's lack of population growth, coupled with low commodity prices for agricultural producers, has significantly hindered growth in the city for two decades.[131]

The lack of growth worsened poverty in the city. There were no neighborhoods of concentrated poverty[lower-alpha 9] in the city in 2010, but by 2016 1,254 city residents lived in such areas. The number of Great Falls residents living in poverty during the same period rose by 10.37 percent (1,100 people),[130] for a citywide poverty rate of 19.9 percent. Great Falls suffered from more concentrated poverty than any other city in the state.[130]

Low economic and population growth have also harmed real estate values in the city. While the median price of a home in five other large Montana cities (Billings, Bozeman, Helena, Kalispell, and Missoula) was $262,960 ($300,000 in 2019 dollars) in 2017, it was just $169,500 ($200,000 in 2019 dollars) in Great Falls during the same period. (That is $93,460, or 35.5 percent, less.) The median price of a home statewide in Montana during that period was $217,200 ($200,000 in 2019 dollars), with Great Falls home prices $47,700, or 22 percent, less.[133]

A 2016 report by the Bureau of Business and Economic Development at the University of Montana predicted the city's economy would be driven by manufacturing, retail sales, and tourism over the next several years.[132] The city had long tried to rebuild its agricultural processing industry, and egg production and specialty milling both saw expanded operations in the city in 2015. In 2016, the city won an $8 million grant from the state of Montana to open a Food and Ag Development Center (only one of four in Montana). Working with BNSF Railway, the city's development agency converted 197 acres (80 ha) of disused railroad yard into a fully service heavy industrial food and agricultural processing site. Named AgriTech Park, the site won an Excellence in Regional Transportation Award from the National Association of Development Organizations. FedEx Ground, Helena Chemical, Montana Specialty Mills, Pacific Steel and Recycling,[134] and Cargill all took space in the park by the end of 2018.[135]

Military

Great Falls is home to Malmstrom Air Force Base and the 341st Missile Wing. The 341st Operations Group provides the forces to launch, monitor and secure the wing's Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and missile alert facilities (MAF). These ICBMs and MAFs are dispersed over the largest missile complex in the Western Hemisphere, an area encompassing some 23,000 sq mi (60,000 km2) (approximately the size of the state of West Virginia). The group manages a variety of equipment, facilities, and vehicles worth more than $5 billion. The 819th RED HORSE Squadron and the 219th RED HORSE Squadron (MTANG), both rapid deployment units, are also located at Malmstrom AFB. The Malmstrom squadrons is the first "associate" RED HORSE squadrons in the Air Force, approximately two-thirds active-duty and one-third Air National Guard (the Montana Air National Guard 219th RED HORSE Squadron). The 819th RED HORSE squadron was reactivated Aug. 8, 1997, at Malmstrom AFB.

Great Falls International Airport is home to the Montana Air National Guard's 120th Airlift Wing. The 120AW is composed of C-130 Hercules (C-130H) cargo aircraft and associated support personnel.

Great Falls is also home to the 889th Army Reserve Unit.

Arts and culture

Great Falls has a symphony orchestra, founded in 1959, which generally offers multiple concert series throughout the year, also sponsoring a Youth Orchestra, the Cascade String Quartet, the Chinook Winds Quintet, other chamber ensembles and an educational outreach program. Well-known performers brought in to perform with Great Falls Symphony have included Yo-Yo Ma, Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Joshua Bell, James Galway, Christopher Parkening and Evelyn Glennie.[136]

The community also is notable for the unique Sip 'n Dip Lounge, a tiki bar located downtown in the O'Haire Motor Inn. Built in 1962, it features an indoor swimming pool visible through a window in the bar where women dressed as mermaids swim underwater. In 2003, GQ magazine rated the lounge as one of the top 10 bars in the world,[137] and the #1 bar in the world "worth flying for".[138] With the added feature of an octogenarian piano player named "Piano Pat," noted for her "unusual covers" of songs by Frank Sinatra and other performers of the 1960s, Frommer's travel guide calls it "one of the kitschiest, wackiest, and flat-out coolest nightspots, not just in Montana, but in the entire West."[139]

Four Seasons Arena

The Four Seasons Arena is a multi-purpose indoor sports and exhibition arena located in the city of Great Falls, Montana, in the United States. Constructed in 1979, it served primarily as an ice rink until 2005. The failure of the practice rink's refrigeration system in 2003 and the management's decision to close the main rink in 2006 led to the facility's reconfiguration as an indoor sports and exhibition space. As of May 2011 it was the largest exhibition, music, and sports venue in the city.

Sports

| Club | Sport | League | Stadium (or arena) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Great Falls Voyagers | Baseball | Pioneer League | Centene Stadium |

| Great Falls Gladiators | Football | Rocky Mountain Football League | Memorial Stadium |

| Great Falls Americans | Ice Hockey | North American 3 Hockey League | Great Falls Ice Plex |

For the 1979–80 WHL season, Great Falls and the Four Seasons Arena was the home of the Great Falls Americans hockey team (see below). The team was 2–25 before folding. Great Falls has a rich baseball history with the Voyagers. Formerly called the White Sox, Dodgers and Giants, baseball players such as Pedro Martínez, José Offerman, and Raúl Mondesí have spent time in Great Falls with the team. Since 1988, the team has won the Pioneer League championship six times (1988, 1989, 1990, 2002, 2008, and 2011). In 2007, the Great Falls Explorers basketball team were the CBA National Conference Runner-up.

Great Falls has been home to the Great Falls Americans Junior A ice hockey team since the 2011–2012 season.

Great Falls is home to the Great Falls Gladiators semi-professional football team. The Gladiators are currently the defending Rocky Mountain Football League champions, recording an 11–0 record and winning the AA division championship at home in Memorial Stadium.

Education

There are 20 schools within the Great Falls Public Schools system. These include two public high schools, an alternative high school, two middle schools, and 15 elementary schools.[140] The two public high schools are Great Falls High School and Charles M. Russell High School. The alternative high school is Paris Gibson Education Center, located in the former Paris Gibson Junior High School building. The two middle schools are North Middle School and East Middle School.

Great Falls also is home to many private schools, all of them sponsored by religious organizations. The Catholic Church sponsors several schools in the city, including Great Falls Montessori (grades Pre-K to K), Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic School (Pre-K to grade 8), Holy Spirit Catholic School (Pre-K to grade 8), and Great Falls Central Catholic High School (grades 9 to 12). The Conservative Baptist Association of America sponsors two schools in the city: Heritage Baptist School (K to grade 9) and Treasure State Baptist Academy (Pre-K to grade 12). The Seventh-day Adventist Church also sponsors two schools: Adventist Christian (grades 1 to 8) and Five Falls Christian Church (grades 1 to 8). There is also a nondenominational Christian school, Foothills Community Christian School (Pre-K to grade 12).

Great Falls is home to three institutions of higher education. Great Falls College Montana State University is a two-year public institution of higher learning. It was founded as the Great Falls Vocational-Technical Center in 1969, and received its current name after the state restructured the two-year comprehensive colleges in the state in 2012. Although a public institution since its creation, it became part of the Montana University System in 1994. The University of Providence, formerly named the University of Great Falls, a private, four-year Catholic university, was founded in 1932 by the Sisters of Providence and the Ursuline Sisters. Apollos University is a private, distance education university, founded in 2005 and headquartered in Great Falls since 2016.

Great Falls has a public library, the Great Falls Public Library.[141]

Media

FM radio

Television

Newspapers

The Great Falls Tribune is published in Great Falls. Great Falls is the second largest media market in the state of Montana.

Infrastructure

The sewage treatment for the city was awarded to Envirotech in 1977, and was renewed with the same company through at least 1982.[142]

Transportation

Great Falls is served by Great Falls International Airport, with four passenger and five cargo airlines. Of those, only Allegiant Air and Fed Ex Express provide service to the city with mainline (large) jet aircraft.

Notable people

- Valeen Tippetts Avery, biographer and historian

- Walter Breuning (1896–2011), once the oldest man in the world

- Mal Bross, National Football League player

- James R. Browning, judge and former Chief Judge on U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and former clerk of U.S. Supreme Court

- Dorothy Coburn, silent-movie actress

- Walter Coy, actor

- Brian Coyle, Minnesota community leader and gay activist

- Scott Davis, two-time U.S. Figure Skating Championships gold medalist

- Dave Dickenson, Canadian Football League quarterback

- Patrick Dwyer, National Hockey League player

- Cory Fong, North Dakota State Tax Commissioner

- Todd Foster, Olympic boxer

- Norman A. Fox, Western author

- Ted Geoghegan, horror filmmaker

- John Gibbons, Major League Baseball manager

- Paris Gibson, U.S. Senator, city founder[143]

- Missy Gold, child actress on Benson

- Tyler Graham, professional baseball player

- Melony G. Griffith, member of Maryland House of Delegates

- A.B. Guthrie, Jr., Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Way West

- Malcolm Hancock, magazine cartoonist

- Charles S. Hartman, U.S. Representative from Montana[144]

- Paul G. Hatfield, Federal District Court Judge (1979 to 2000), former U.S. Senator, former Chief Justice of the Montana Supreme Court, former Montana state District Court Judge[145]

- Lester Hogan, pioneer in microwave and semiconductor technology

- George Horse-Capture, Native American activist and museum curator

- Joseph Kinsey Howard, author and historian

- Josh Huestis, NBA player

- Patrick M. Hughes, Lieutenant General, United States Army, Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, 1996–1999[146]

- Alma Smith Jacobs, director, Great Falls Public Library; first African American Montana State Librarian

- Jay L. Johnson, U.S. Navy admiral, Chief of Naval Operations

- Raymond A. Johnson, aviation pioneer, worked at Great Falls airport in 1940s[147]

- Nathaniel Bar Jonah, convicted kidnapper, child molester, suspected serial killer and cannibal

- Edward McKnight Kauffer, early 20th-century graphic designer and poster artist

- Pert Kelton, actress, the original Alice Kramden on The Honeymooners

- Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips

- Ryan Leaf, former NFL quarterback

- Barbara Luddy, actress

- Howard Lyman, vegetarian activist

- Mike Mansfield, U.S. Representative, Senator, longest-serving Senate majority leader, U.S. Ambassador to Japan[148]

- Linda McDonald, drummer in all-girl metal band Phantom Blue

- Cyra McFadden, writer

- Hugh Mitchell, served in United States Senate 1945–1946 and House of Representatives 1949–1953 for the state of Washington[149]

- Gerald R. Molen, Academy Award-winning film producer

- George Montgomery, actor, painter, sculptor and stuntman, born in nearby Brady

- Matt Morrison, Fox Sports Net sportscaster

- Andrew Nelson, Japanese-language lexicographer

- Tom Neville, NFL player

- Tera Patrick, adult film actress

- John Misha Petkevich, U.S. Figure Skating Championships gold medalist

- Charles Nelson Pray, former U.S. Representative from Montana[150]

- Charley Pride, country singer

- Traver Rains, half of the New York fashion design duo Heatherette

- Merle Greene Robertson, artist, art historian, archaeologist, and Mayan researcher

- Hannah Rose, Christian musician

- William V. Roth, Jr., U.S. Representative and Senator from Delaware[151]

- Charles Marion Russell, western artist

- Brian Salonen, tight end for the Dallas Cowboys

- Jaymee Sire, ESPN sportscaster

- Jon Steele, American expat author

- Wallace Stegner, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Angle of Repose

- Haila Stoddard, actress, writer, producer and director

- Anton D. Strouf, Montana and Wisconsin state legislator, lawyer

- Gary W. Thomas, California state judge

- Edward L. Thrasher, Los Angeles, City Council member 1931–1942, born in Great Falls

- Al Ullman, U.S. Congressman from Oregon[152]

- Thomas C. Wasson (1896–1948), diplomat who was killed while serving as the Consul General for the United States in Jerusalem[153]

- Reggie Watts, comedian, musician, performance artist

- John Warner, justice of the Montana Supreme Court

- Irving Weissman, scientist

- Bill Zadick, wrestler

- Mike Zadick, wrestler

In popular culture

Several motion pictures have been filmed in Great Falls. These include:

- Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)[154][lower-alpha 10]

- Telefon (1977)[156][lower-alpha 11]

- The Stone Boy (1983)[159]

- Unsolved Mysteries (Season 3, Episode 12; 1990)[160]

- Holy Matrimony (1994)[155][lower-alpha 12]

- The Slaughter Rule (2002)[155][lower-alpha 13]

- Northfork (2003)[162][lower-alpha 14]

- Iron Ridge (2008)[165]

- The Vessel (2009)[166]

- Reborn (2008)[167][168]

- Tomorrow Will Be... (2010)[168][169]

- Who's in the Mirror (2013)[170]

- The Best Bar in America (2013)[171][lower-alpha 15]

The Mariana UFO incident

The Mariana UFO incident occurred in August 1950 in Great Falls. Nicholas "Nick" Mariana, the general manager of the Great Falls "Electrics" minor-league baseball team, and his secretary observed two "bright, silvery spheres" move rapidly over the city's empty baseball stadium. Mariana used his camera to film the objects; the film was one of the first ever taken of a suspected UFO. The event received widespread national publicity and is regarded as one of the first great UFO incidents in the United States. In 2007, the Great Falls White Sox were renamed as the Great Falls Voyagers to commemorate this event. The team logo features a green alien in a flying saucer.

Sister city

Great Falls has one sister city, as designated by Sister Cities International (SCI): Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada.

See also

Notes

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- The Great Northern Railay opened coal mines in Cascade County in the 1890s, making Great Falls a leader in coal production in the state.[74]

- Montana farmers engaged in deep plowing of the topsoil. The unanchored soil turned to dust in drought conditions, and the winds heavily eroded the topsoil.[76]

- The price of a bushel of wheat nearly halved, dropping from $2.40 to $1.25.[76]

- The state made 10th Avenue S. a state highway in October 1933.[99] Prior to the construction of the Warden Bridge, west-bound traffic had to take a convoluted route through the city to cross the Missouri River: Traffic entering from the east would turn north on E. 57th Street, turn west on 2nd Avenue N., turn south on Park Drive, and cross the river using the Central Avenue Bridge. Most traffic then traveled west on Central Avenue W. before turning south on 6th Street SW to cross the Sun River and connect with U.S. Route 91. This forced nearly all traffic through the city's main business district.[100]

- 10th Avenue S. was "one of the first in Montana to be designed and constructed with a center median and left-turn bays."[98]

- Since 1933, the college had been located in a disused nursing school building located on the southwest corner of 3rd Avenue N. and 17th Street N. on the campus of Columbus Hospital.[103] The college built the McLaughlin Center, a recreation center with gymnasium and swimming pool, in 1964.[104]

- The 29th Fighter-interceptor Squadron was activated and assigned to Malmstrom in November 1953. The unit was inactivated in July 1968,[118] with a loss of 300 jobs.[119] The newly-inactivated 71st Fighter-Interceptor Squadron[120] was reactivated and assigned to Malmstrom in its place in July 1968.[121] Redesignated the 319th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron in July 1971,[122] the unit was inactivated in April 1972 with the loss of 476 airmen and officer jobs.[117]

- Concentrated poverty is defined as a neighborhood where more than 40 percent of the residents have an income below the federal poverty line.[130]

- Shot in Cascade County and in the city of Great Falls, the film's climactic moment features George Kennedy's character driving a car through the main window of The Paris department store, at the corner of 4th Street and Central Avenue. Another scene shows Jeff Bridges' character walking on 4th Street on the same corner. Tracy's restaurant and the Great Falls Civic Center can be seen in the same scene.[155]

- Filming sites included the Great Falls International Airport and the historic F-89 (Aircraft 53-2547) mounted there.[157] A 1913 brick annex to the Paris Gibson Square Museum of Art was blown up for one of the film's opening scenes.[158]

- Filmed both in Cascade County[154] and in the city of Great Falls, the city scenes include shots of Joseph Gordon-Levitt's character outside Tracy's restaurant, and Patricia Arquette's character inside the restaurant.[155] The Montana State Fair at the Montana ExpoPark stood in for the Iowa State Fair in the film.[161]

- Filming occurred inside the Saatz Block building on the corner of 4th Street South and 2nd Avenue South. This served as the apartment in which Ryan Gosling and David Morse discuss football.[155]

- Although primarily filmed outside Cascade County,[163] the film had an office in Great Falls, and cast and crew stayed in the city.[164] One scene was filmed at Giant Springs State Park on the immediate outskirts of the city.[162]

- Scenes were filmed at the Sip 'n Dip Lounge in Great Falls.[171]

Citations

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Great Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas". Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- US Census Bureau, Public Information Office. "Census 2000 data for Montana". census.gov. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Malone, Michael P.; Roeder, Richard B.; and Lang, William L. Montana: A History of Two Centuries. 2d rev. ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003. ISBN 0-295-97129-0

- Federal Writers' Project. Montana: A State Guide Book. Washington, D.C.: Federal Works Agency, Work Projects Administration, 1939. ISBN 1-60354-025-3

- Fleming, Thomas J. The Louisiana Purchase. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, 2003. ISBN 0-471-26738-4

- Ambrose, Stephen. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. ISBN 0-684-82697-6; Gilman, Carolyn. Lewis and Clark: Across the Divide. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2003. ISBN 1-58834-099-6; Lavender, David. The Way to the Western Sea: Lewis and Clark Across the Continent. New York: Harpercollins, 1988. ISBN 0-06-015982-0

- Pritchett, Michael. The Melancholy Fate of Capt. Lewis. Columbia, Mo.: Unbridled Books, 2007. ISBN 1-932961-41-0

- Betts, Robert B. In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific With Lewis and Clark. Boulder, Colo.: Colorado Associated University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0-87081-714-4; Hancock, Sibyl. Famous Firsts of Black Americans. Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing Company, 1983. ISBN 0-88289-240-1; Doig, Ivan. English Creek. New York: Atheneum, 1984. ISBN 0-689-11478-8

- Saindon, Robert A. Explorations into the World of Lewis and Clark. Vol. 3. Scituate, Mass.: Digital Scanning Inc, 2003. ISBN 1-58218-766-5

- O'Neal, Bill. Fighting Men of the Indian Wars: A Biographical Encyclopedia of the Mountain Men, Soldiers, Cowboys, and Pioneers Who Took Up Arms During America's Westward Expansion. Stillwater, Okla.: Barbed Wire Press, 1991. ISBN 0-935269-07-X

- Allen, John Logan. North American Exploration: A Continent Comprehended. Vol. 3. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8032-1043-4

- McManus, Sheila. The Line Which Separates: Race, Gender, and the Making of the Alberta-Montana Borderlands. Calgary: University of Alberta, 2005. ISBN 0-88864-434-5; Evans, Sterling. The Borderlands of the American and Canadian Wests: Essays on Regional History of the Forty-Ninth Parallel. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8032-1826-5

- Tubbs, Stephenie Ambrose and Jenkinson, Clay. The Lewis and Clark Companion: An Encyclopedic Guide to the Voyage of Discovery. New York: Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-8050-6726-4; Miller, James Knox Polk. The Road to Virginia City: The Diary of James Knox Polk Miller. Stillwater, Okla.: University of Oklahoma, 1960.

- "Opinion analysis: Montana dunked on riverbeds". SCOTUSblog. February 23, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- Cutright, Paul Russell and Brodhead, Michael J. Elliott Coues: Naturalist and Frontier Historian. Reprint ed. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2001. ISBN 0-252-06987-0

- Luebke, Frederick C. Nebraska: An Illustrated History. 2d ed. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8032-8042-4

- Lamar, Howard Roberts. Dakota Territory, 1861–1889: A Study of Frontier Politics. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1956; History of Southeastern Dakota. Sioux City, Iowa: Western Publishing Company, 1881.

- Rees, John E. Idaho Chronology, Nomenclature, Bibliography. Chicago: W.B. Conkey Co., 1918.

- Roeder, Richard B. "Paris Gibson and the Building of Great Falls." Montana: Magazine of Western History. 42:4 (Autumn 1992).

- "Great Falls, Montana." In Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. David J. Wishart, ed. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8032-4787-7

- Malone, Michael P. James J. Hill: Empire Builder of the Northwest. Reprint ed. Stillwater, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8061-2860-7

- Myers, Rex C. and Fritz, Harry W. Montana and the West: Essays in Honor of K. Ross Toole. Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Co., 1984. ISBN 0-87108-229-2; Martin, Albro. James J. Hill and the Opening of the Northwest. St. Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1991. ISBN 0-87351-261-8

- Lutz, Dennis J. Montana Post Offices & Postmasters, p 24, p. 200. (1986) Minot, ND: published by the author & Montana Chapter No. 1, National Association of Postmasters of the United States.

- Bailey, Vernon (1894), "Belt to Great Falls", Journal,

Aug. 31, Climbed out of the Otter Creek valley and struck N.W. across rolling prairie to Great Falls. Could see the smelter Chimneys as soon as we reached the top of prairie 3 miles from Belt. Struck no water till we reached Great Falls city. This is a very good town, appears prosperous and booming & I should judge contains 15000 inhabitants.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- Boerner, D.E.; Craven, J.A.; Kurtz, R.D.; Ross, G.M.; and Jones, F.W. "The Great Falls Tectonic Zone: Suture or Intracontinental Shear Zone?" Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 35:2 (1998); O'Neill, J. Michael and Lo, David A. "Character and Regional Significance of Great Falls Tectonic Zone, East-Central Idaho and West-Central Montana." AAPG Bulletin. 69 (1985); Mueller, Paul A.; Heatherington, Ann L.; Kelly, Dawn M.; Wooden, Joseph L.; and Mogk, David W. "Paleoproterozoic Crust Within the Great Falls Tectonic Zone: Implications for the Assembly of Southern Laurentia." Geology. 30:2 (February 2002); Harms, Tekla A.; Brady, John B.; Burger, H. Robert; and Cheney, John T. ‘Advances in the Geology of the Tobacco Root Mountains, Montana, and Their Implications for the History of the Northern Wyoming Province.’ Precambrian geology of the Tobacco Root Mountains, Montana. Special Papers, Volume 377. John B. Brady, H. Robert Burger, John T. Cheney, and Tekla A. Harms, eds. Boulder, Colo.: Geological Society of America, 2004. ISBN 0-8137-2377-9

- Clawson, Roger and Shandera, Katherine A. Billings: The City and the People. Helena, Mont.: Farcountry Press, 1998. ISBN 1-56037-037-8

- McRae, W.C. and Jewell, Judy. Moon Montana. 7th ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: PublicAffairs, 2009. ISBN 1-59880-014-0

- Montagne J.L. 'Quaternary System, Wisconsin Glaciation.' Geologic Atlas of the Rocky Mountain Region. Denver: Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists, 1972.

- Feathers, James K. and Hill, Christopher L. "Luminescence Dating of Glacial Lake Great Falls, Montana, U.S.A." Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine XVI International Quaternary Association Congress. Stratigraphy and Geochronology Session. International Quaternary Association, Reno, 2003.

- Hill, Christopher L. and Valppu, Seppo H. "Geomorphic Relationships and Paleoenvironmental Context of Glaciers, Fluvial Deposits, and Glacial Lake Great Falls, Montana." Current Research in the Pleistocene. 14 (1997); Hill, Christopher L. "Pleistocene Lakes Along the Southwest Margin of the Laurentide Ice Sheet." Current Research in the Pleistocene. 17 (2000); Hill, Christopher L. and Feathers, James K. "Glacial Lake Great Falls and the Late-Wisconsin-Episode Laurentide Ice Margin." Current Research in the Pleistocene. 19 (2002); Reynolds, Mitchell W. and Brandt, Theodore R. Geologic Map of the Canyon Ferry Dam 30' x 60' Quadrangle, West-Central Montana: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 2860, scale 1:100,000. Scientific Investigations Map 2860. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geologic Survey, 2005.

- "Agriculture." In Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. David J. Wishart, ed. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8032-4787-7

- Axline, Jon and Bradshaw, Glenda Clay. Montana's Historical Highway Markers. Rev. ed. Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society, 2008. ISBN 0-9759196-4-4; Bowman, Isaiah. "Forest Physiography: Physiography of the United States and Principles of Soils in Relation to Forestry." American Environmental Studies. Reprint ed. Charles Gregg, ed. New York: Arno Press, 1970. ISBN 0-405-02659-5

- "Great Falls, Montana Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- NOW; NOAA Online Weather Data, Great Falls, Montana

- "Climatography of the United States No. 20 1971–2000: GREAT FALLS INTL AP, MT" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- "NOAA". NOAA.

- Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 131.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- Holmes 1913, p. 341.

- Peterson 2010, p. 59.

- Marcosson 1957, p. 45.

- Holmes, Dailey & Walter 2008, p. 397.

- Record, Historic American Engineering. "Black Eagle Hydroelectric Facility, Great Falls, Cascade County, MT". www.loc.gov.

- "City's Past Rooted in the River That Runs Through It". Great Falls Tribune. March 24, 2002.

- Hofman 1904, pp. 267-269.

- Furdell 2002, p. 203.

- Mutschler 2002, p. 13.

- Taliaferro 2003, p. 121.

- Peterson 2010, p. 43.

- Farley 1965, p. 221.

- "State Agricultural Society". Great Falls Tribune. January 12, 1895. p. 4.

- "The Cascade County Fair". Great Falls Tribune. May 12, 1895. p. 6; "The First Day of the Fair". Great Falls Tribune. October 2, 1895. p. 4.

- Curry 1920, p. 1343.

- Holmes 1913, p. 354.

- Curry 1920, p. 1318.

- Peterson 2010, p. 42.

- "Great Falls Enlarges Elevator Capacity". Commercial West. June 23, 1917. p. 36. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "Montana Flour Mills Join in Large Merger". The Missoulian. June 27, 1928. p. 5.

- Peterson 2010, p. 28.

- Federal Writers' Project 1939, p. 150.

- Wilmot, Paula (January 26, 2006). "Clinic Buys Surgical Hospital". Great Falls Tribune.

- "Great Falls Bank Deposits Gain $5,000,000". Commercial West. March 31, 1917. p. 35. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Howard 2003, p. 229.

- Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 179, 337-338.

- Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, pp. 280-281.

- Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 281.

- Spence 1978, p. 137.

- Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 338.

- Furdell 2002, p. 204.

- Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 295.

- Spence 1978, p. 146.

- Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 283.

- Spence 1978, p. 140.

- Spence 1978, pp. 139-140.

- Farley 1965, p. 166.

- Furdell 2002, p. 202.

- Furdell 2002, p. 213.

- Furdell 2002, p. 214.

- Peterson 2010, p. 94.

- Farley 1965, p. 192.

- Holmes, Dailey & Walter 2008, p. 404.

- Farley 1965, p. 222.

- Wyckoff 2006, p. 14.

- Farley 1965, p. 167.

- Mercier 2001, p. 185.

- Malone, Roeder & Lang 1991, p. 325.

- Farley 1965, p. 17.

- Farley 1965, p. 5.

- Farley 1965, p. 1.

- Farley 1965, pp. 1, 5.

- Farley 1965, p. 26.

- Farley 1965, pp. 17, 27, 37.

- LaPorte, Margaret (1992). Columbus Hospital—One Hundred Years (PDF). Great Falls, Mont.: Sisters of Providence. pp. 23–24.

- Farley 1965, p. 29.

- "Holiday Village Has Grand Opening Today". Great Falls Tribune. January 20, 1960.

- "Early December Grand Opening Planned at Holiday Village". Great Falls Tribune. November 12, 1967; "New Buttreys Opens Tuesday". Great Falls Tribune. July 27, 1969.

- "Small Great Falls mall to be razed". Associated Press. April 7, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- National Research Bureau (1992). Shopping Center Directory. Volume 4. Chicago: National Research Bureau. p. 525. OCLC 31813898.

- "Mini Shopping Mall Proposed". Great Falls Tribune. May 22, 1983. p. 41; Kerin, Tom (January 1, 1984). "Great Falls Construction Up Sharply in 1983". Great Falls Tribune. p. 17.

- Farley 1965, p. 168.

- "Plans Drafted for Livestock Market". Helena Independent-Record. February 9, 1936. p. 14.

- Farley 1965, p. 171.

- Farley 1965, pp. 171-172.

- Farley 1965, p. 173.

- Mutschler 2002, p. 14.

- "And in Butte—Silence". The Billings Gazette. July 2, 1971. p. 17.

- "Malmstrom Cutback Cost Heavy". The Montana Standard. April 4, 1972. p. 9.

- Cornett & Johnson 1980, pp. 115.

- "At Malmstrom AFB... Sophisticated Preliminaries Precede Voodoo Takeoffs". Great Falls Tribune. February 26, 1967. p. 92.

- Cornett & Johnson 1980, p. 118.

- "MAFB to Officially Welcome 71st FIS". Great Falls Tribune. July 11, 1968. p. 36.

- Cornett & Johnson 1980, p. 125.

- "Malmstrom Squadron to Be Inactivated". The Missoulian. June 28, 1974. p. 10.

- Rice, Ronald J. (October 15, 1979). "View From Malmstrom: Interested City". Great Falls Tribune. p. 1; "Relief, Acceptance Greet Malmstrom Cutbacks". Great Falls Tribune. March 30, 1979. p. 21.

- "More Malmstrom Cutbacks". Billings Gazette. December 14, 1981. p. 19.

- "Post to Close in June". Great Falls Tribune. March 20, 1982. p. 16.

- Rice, Ronald J. (May 31, 1983). "End Near for NORAD's 24th". Great Falls Tribune. p. 11.

- "Malmstrom's Impact Shrinks". Helena Independent Record. January 29, 1985. p. 13.

- Downey, Mark; Johnson, Peter (October 1, 1996). "Final Tanker Flies to Florida". Great Falls Tribune. p. 1.

- Comen, Evan; Stebbins, Samuel (July 13, 2018). "What city is hit hardest by extreme poverty in your state?". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Bureau of Business and Economic Development 2018, pp. 6-7.

- Johnson, Peter (January 27, 2016). "Experts project favorable economy for Great Falls, state". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Bureau of Business and Economic Development 2018, p. 21.

- "Great Falls, Montana Chosen As Food and Ag Development Center". Business Facilities. November 2, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "Cargill opens lab in Great Falls to begin omega-3 research and development". Helena Independent Record. December 10, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "The Great Falls Symphony " About Us". gfsymphony.org. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- "MATR News: Quirky Sip-N-Dip (Great Falls) makes splash on GQ magazine's top 10 bars in the world". Matr.net. March 31, 2003. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- "Official State of Montana Vacation, Recreation, Accommodations and Travel Information Website". visitmt.com. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- "Nightlife in Great Falls". Frommers.com. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- Great Falls Public Schools website Great Falls Public School System.

- "Montana Public Libraries". PublicLibraries.com. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- Johnson, Peter (March 28, 1980). "For sewage-treatment plants". Great Falls Tribune. p. 7–A – via Newspapers.com (Publisher Extra).

- "Paris Gibson". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Charles S. Hartman". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Paul G. Hatfield". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "MSU Graduates More Than 2,000 Students." Associated Press. May 9, 1999.

- "Raymond Johnson named to Wyoming Aviation Hall of Fame, September 23, 2013". Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- "MANSFIELD, Michael Joseph (Mike), (1903–2001)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Hugh Mitchell". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Charles Nelson Pray". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "William V. Roth, Jr.". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Al Ullman". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Staff. "Wasson Long In Service; Started as Clerk in the Melbourne Consulate in 1924", The New York Times, May 23, 1948. Accessed March 7, 2018. "Mr. Wasson was born in Great Falls, Mont., on Feb, 8, 1896, the son of Edmund Atwill and Mary DeVeny Wasson, His family moved to Newark, N. J., shortly after his birth and he received his schooling in the Newark grammar and high schools."

- "Montana's best and worst all-time films". Great Falls Tribune. November 6, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Douglas, Patrick (March 18, 2016). "Does Great Falls have a Hollywood Boulevard?". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Rosenbaum, Traci (October 27, 2016). "From school to Square: Great Falls' beloved building turns 120". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Bright, Christopher (2010). Continental Defense in the Eisenhower Era: Nuclear Antiaircraft Arms and the Cold War. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 81. ISBN 9780230112926.

- Madison, Erin (July 11, 2010). "Square's Past Saw Students, Explosion". Great Falls Tribune. p. 12; Wilmot, Paula (September 12, 2010). "Quiz Answers: 1970s Saw Big Changes in Electric City". Great Falls Tribune. p. M1.

- Jones, Robert F. (April 23, 1984). "Robert Duvall". People. Retrieved May 2, 2017; Nash, Jay Robert; Ross, Stanley Ralph (1985). The Motion Picture Guide. W-Z, 1922–1984. Chicago: Cinebooks.

- "10 Montana 'Unsolved Mysteries' cases". Billings Gazette. March 31, 2017. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Gordon, William A. (1995). Shot on This Site: A Traveler's Guide to the Places and Locations Used to Film Famous Movies and TV Shows. New York: Carol Publishing Group. p. 65. ISBN 9780806516479.

- Gaiser, Heidi (March 3, 2007). "Family Men". The Daily Inter Lake. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Inbody, Kristen (December 29, 2016). "'Shot in Montana': Big Sky Cinema is scope of new book". USA Today. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- "Nolte, others filming 'Northfork' in Great Falls area". Associated Press. May 4, 2002. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Skornogoski, Kim (June 13, 2006). "Getting One's Life Experience on Film No Easy Task For Great Falls' Brumbaugh". Great Falls Tribune. p. M1; Testa, Dan (March 28, 2008). "Weekend Buffet: Tester Questioned on Economy, 3,000 Bison, $35 Movie Ticket". Flathead Beacon. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Murphy, Andi (July 18, 2008). "Auditions tonight for local horror film". Great Falls Tribune. p. M3; Dodd, Jeni (October 31, 2008). "Horror flick filmed in Great Falls, 'The Vessel,' to show Nov. 21". Great Falls Tribune. p. T3.

- Ecke, Richard (September 1, 2008). "Filming returns to city with low-budget 'Reborn'". Great Falls Tribune. p. M1.

- Ecke, Richard (September 16, 2013). "Montana movies a part of fall films". Great Falls Tribune. pp. M1, M3.

- "Local filmmaker Gerald Bickel premieres newest film, 'Tomorrow Will Be ...,' in Great Falls Saturday". Great Falls Tribune. November 13, 2009. p. 2.

- Sorich, Jake (September 20, 2013). "Local filmmaker unveils film 'Who's in the Mirror'". Great Falls Tribune. p. H2.

- Cederberg, Jenna (September 6, 2013). "Long road to release party for 'Best Bar in America'". The Missoulian. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

Bibliography

- Bureau of Business and Economic Development (2018). 2018 Montana Economic Report (PDF) (Report). Missoula, Mont.: University of Montana. Retrieved March 29, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cornett, Lloyd H.; Johnson, Mildred W. (1980). A Handbook of Aerospace Defense Organization, 1946–1980 (PDF). Peterson AFB, Colo.: Office of History, Aerospace Defense Center.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curry, John A. (December 15, 1920). "The Story of Great Falls". Northwestern Miller. Retrieved March 28, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farley, John T. (1965). Economic Impact of the Growth of Tenth Avenue South Upon the Economy of Great Falls, Montana: 1940-1965 (Report). Great Falls, Mont.: College of Great Falls. Retrieved April 10, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). Montana: A State Guide Book. New York: Viking Press. OCLC 19490170.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Furdell, William J. (2002). "The Great Falls Home Front During World War II". In Fritz, Harry W.; Murphy, Mary; Swartout, Robert R. (eds.). Montana Legacy: Essays on History, People, and Place. Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 9780917298905.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hofman, H.O. (1904). "Notes on the Metallurgy of Copper of Montana". Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers. New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Oliver M. (October 1913). "Progress of Great Falls, Montana". Coast Banker. Retrieved March 28, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Krys; Dailey, Susan C.; Walter, David (2008). Montana: Stories of the Land. Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 9780975919637.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard, Joseph Kinsey (2003). Montana: High, Wide, and Handsome. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803273399.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Krys; dailey, Susan C.; Walter, David (2008). Montana: Stories of the Land. Helena, Mont.: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 9780975919637.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malone, Michael P.; Roeder, Richard B.; Lang, William L. (1991). Montana: A History of Two Centuries. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295971209.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marcosson, Isaac F. (1957). Anaconda. New York: Anaconda Company. OCLC 185693759.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mercier, Laurie (2001). Anaconda: Labor, Community, and Culture in Montana's Smelter City. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252026577.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mutschler, Charles V. (2002). Wired for Success: The Butte, Anaconda and Pacific Railway, 1892–1985. Pullman, Wash.: Washington State University Press. ISBN 9780874222524.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peterson, Don (2010). Great Falls. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738580845.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spence, Clark C. (1978). Montana: A Bicentennial History. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393056792.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taliaferro, John (2003). Charles M. Russell: The Life and Legend of America's Cowboy Artist. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806134956.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wyckoff, William (2006). On the Road Again: Montana's Changing Landscape. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295986128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- MacGibbon, Elma (1904). Leaves of knowledge. Shaw & Borden Co.Available online through the Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection Elma MacGibbon's reminiscences of her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Great Falls, Montana".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Falls, Montana. |

![]()