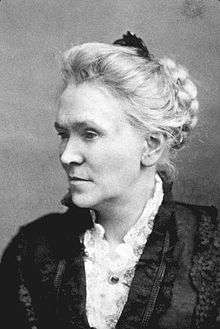

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage (March 24, 1826 – March 18, 1898) was a women's suffragist, Native American rights activist, abolitionist, freethinker, and author. She is the eponym for the Matilda Effect, which describes the tendency to deny women credit for scientific invention.

Matilda Joslyn Gage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Matilda Electa Joslyn March 24, 1826 Cicero, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 18, 1898 (aged 71) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation | abolitionist, free thinker, author |

| Residence | Fayetteville, New York, U.S. |

| Notable works | Author, with Anthony and Stanton, of first three volumes of History of Woman Suffrage |

| Spouse | Henry Hill Gage ( m. 1845) |

| Children | Maud Gage Baum, Charles Henry Gage, Helen Leslie Gage, Julia Louise Gage, Thomas Clarkson Gage |

| Relatives | Hezekiah Joslyn (father); L. Frank Baum, son-in-law |

She was the youngest speaker[1] at the 1852 National Women's Rights Convention held in Syracuse, New York. She was a tireless worker and public speaker, and contributed numerous articles to the press, being regarded as "one of the most logical, fearless and scientific writers of her day". During 1878–1881, she published and edited at Syracuse the National Citizen, a paper devoted to the cause of women. In 1880, she was a delegate from the National Woman Suffrage Association to the Republican and Greenback conventions in Chicago and the Democratic convention in Cincinnati, Ohio. With Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, she was for years in the forefront of the suffrage movement, and collaborated with them in writing the History of Woman Suffrage (1881–1887). She was the author of the Woman's Rights Catechism (1868); Woman as Inventor (1870); Who Planned the Tennessee Campaign (1880); and Woman, Church and State (1893).[2]

Gage served as president of the New York State Suffrage Association for five years, and president of the National Woman's Suffrage Association during 1875–76, which was one of the affiliating societies forming the national suffrage association, in 1890; she also held the office of second vice-president, vice-president-at-large and chairman of the executive committee of the original National Woman Suffrage Association.[2]

Gage's views on suffrage and feminism were considered too radical by many members of the suffrage association, and in consequence, she organized in 1890 the Woman's National Liberal Union,[3] whose objects were: To assert woman's natural right to self-government; to show the cause of delay in the recognition of her demand; to preserve the principles of civil and religious liberty; to arouse public opinion to the danger of a union of church and state through an amendment to the constitution, and to denounce the doctrine of woman's inferiority. She served as president of this union from its inception until her death in Chicago, in 1898.[2]

Early years and education

Matilda Electa Joslyn was born in Cicero, New York, March 24, 1826. Her parents were Dr. Hezekiah and Helen (Leslie) Joslyn. Her father, of New England and revolutionary ancestry, was a liberal thinker and an early abolitionist, whose home was a station of the Underground Railroad, as was also her own home.[4] From her mother, who was a member of the Leslie family of Scotland, Gage inherited her fondness for historic research.[2]

Her early education was received from her parents, and the intellectual atmosphere of her home had an influence on her career. She attended Clinton Liberal Institute, in Clinton, Oneida County, New York.[2]

Early activities

On January 6, 1845, at the age of 18, she married Henry H. Gage, a merchant of Cicero, making their permanent home at Fayetteville, New York.[2]

She faced prison for her actions associated with the Underground Railroad under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 which criminalized assistance to escaped slaves. Even though she was beset by both financial and physical (cardiac) problems throughout her life, her work for women's rights was extensive, practical, and often brilliantly executed.[5]

Gage became involved in the women's rights movement in 1852 when she decided to speak at the National Women's Rights Convention in Syracuse, New York. She served as president of the National Woman Suffrage Association from 1875 to 1876 and served as either Chair of the Executive Committee or Vice President for over twenty years. During the 1876 convention, she successfully argued against a group of police who claimed the association was holding an illegal assembly. They left without pressing charges.[6]

Gage was considered to be more radical than either Susan B. Anthony or Elizabeth Cady Stanton (with whom she wrote History of Woman Suffrage,[7] and Declaration of the Rights of Women).[8] Along with Stanton, she was a vocal critic of the Christian Church, which put her at odds with conservative suffragists such as Frances Willard and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. Rather than arguing that women deserved the vote because their feminine morality would then properly influence legislation (as the WCTU did), she argued that they deserved suffrage as a 'natural right'. Despite her opposition to the Church, Gage was in her own way deeply religious, and she joined Stanton's Revising Committee to write The Woman's Bible.

Writer and editor

Gage was well-educated and a prolific writer—the most gifted and educated woman of her age, claimed her devoted son-in-law, L. Frank Baum. She corresponded with numerous newspapers, reporting on developments in the woman suffrage movement. In 1878, she bought the Ballot Box, the monthly journal of a Toledo, Ohio, suffrage association, when its editor, Sarah R. L. Williams, decided to retire. Gage turned it into The National Citizen and Ballot Box, explaining her intentions for the paper thus:

Its especial object will be to secure national protection to women citizens in the exercise of their rights to vote ... it will oppose Class Legislation of whatever form ... Women of every class, condition, rank and name will find this paper their friend

— Matilda Joslyn Gage, "Prospectus"[9]

Gage became its primary editor for the next three years (until 1881), writing and publishing essays on a wide range of issues. Each edition bore the words 'The Pen Is Mightier Than The Sword', and included regular columns about prominent women in history and female inventors. Gage wrote clearly, logically, and often with a dry wit and a well-honed sense of irony. Writing about laws which allowed a man to will his children to a guardian unrelated to their mother, Gage observed:

It is sometimes better to be a dead man than a live woman.

— Matilda Joslyn Gage, "All The Rights I Want"[10]

Activism

Gage described herself as "born with a hatred of oppression."[11] As a result of the campaigning of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association under Gage, the state of New York granted female suffrage for electing members of the school boards. Gage ensured that every woman in her area (Fayetteville, New York) had the opportunity to vote by writing letters making them aware of their rights, and sitting at the polls making sure nobody was turned away. In 1871, Gage was part of a group of 10 women who attempted to vote. Reportedly, she stood by and argued with the polling officials on behalf of each individual woman. She supported Victoria Woodhull and (later) Ulysses S Grant in the 1872 presidential election. In 1873 she defended Susan B. Anthony when Anthony was placed on trial for having voted in that election, making compelling legal and moral arguments.[12] In 1884, Gage was an Elector-at-Large for Belva Lockwood and the Equal Rights Party.[13]

Gage unsuccessfully tried to prevent the conservative takeover of the women's suffrage movement. Susan B. Anthony, who had helped to found the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), was primarily concerned with gaining the vote, an outlook which Gage found too narrow. Conservative suffragists were drawn into the suffrage movement believing women's vote would achieve temperance and Christian political goals. These women were not in support of general social reform. The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), part of the conservative wing of the suffrage movement (and formerly at odds with the National), was open to the prospect of merging with the NWSA under Anthony, while Anthony was working toward unifying the suffrage movement under the single goal of gaining the vote. The merger of the two organizations, pushed through by Lucy Stone, Alice Stone Blackwell and Anthony, produced the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1890. Stanton and Gage maintained their radical positions and opposed the merger of the two suffrage associations because they believed it was a threat to separation of church and state. The successful merger of the two suffrage groups prompted Gage to establish the Woman's National Liberal Union (WNLU) in 1890, of which she was president until her death (by stroke) in 1898. Attracting more radical members than NAWSA, the WNLU became the platform for radical and liberal ideas of the time. Gage became the editor of the official journal of the WNLU, The Liberal Thinker.

Gage was an avid opponent of the Christian church as controlled by men, having analyzed centuries of Christian practices as degrading and oppressive to women.[14][15][16] She saw the Christian church as central to the process of men subjugating women, a process in which church doctrine and authority were used to portray women as morally inferior and inherently sinful. She strongly supported the separation of church and state, believing "that the greatest injury to women arose from theological laws that subjugated woman to man." She wrote in October 1881:

Believing this country to be a political and not a religious organisation ... the editor of the National Citizen will use all her influence of voice and pen against "Sabbath Laws", the uses of the "Bible in School", and pre-eminently against an amendment which shall introduce "God in the Constitution".

— "God in the Constitution", page 2

In 1893, she published Woman, Church and State, a book that outlined the variety of ways in which Christianity had oppressed women and reinforced patriarchal systems. It was wide-ranging and built extensively upon arguments and ideas she had previously put forth in speeches (and in a chapter of History of Woman Suffrage which bore the same name). Gage became a Theosophist, and the last two years of her life, her thoughts were concentrated upon metaphysical subjects, and the phenomena and philosophy of Spiritualism and Theosophical studies. During her critical illness in 1896, she experienced some illuminations that intensified her interest in psychical research. She had great interest in the occult mysteries of Theosophy and other Eastern speculations as to reincarnation and the illimitable creative power of man.[17]

Like many other suffragists, Gage considered abortion a regrettable tragedy, although her views on the subject were more complex than simple opposition. In 1868, she wrote a letter to The Revolution (a women's rights paper edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Parker Pillsbury), supporting the view that abortion was an institution supported, dominated and furthered by men. Gage opposed abortion on principle, blaming it on the 'selfish desire' of husbands to maintain their wealth by reducing their offspring:

The short article on "Child Murder" in your paper of March 12 that touched a subject which lies deeper down in woman's wrongs than any other. This is the denial of the right to herself ... nowhere has the marital union of the sexes been one in which woman has had control over her own body. Enforced motherhood is a crime against the body of the mother and the soul of the child. ... But the crime of abortion is not one in which the guilt lies solely or even chiefly with the woman. ... I hesitate not to assert that most of this crime of "child murder", "abortion", "infanticide", lies at the door of the male sex. Many a woman has laughed a silent, derisive laugh at the decisions of eminent medical and legal authorities, in cases of crimes committed against her as a woman. Never, until she sits as juror on such trials, will or can just decisions be rendered.

— Matilda Joslyn Gage, "Is Woman Her Own?"

Gage was quite concerned with the rights of a woman over her own life and body. In 1881 she wrote, on the subject of divorce:

When they preach as does Rev. Crummell, of "the hidden mystery of generation, the wondrous secret of propagated life, committed to the trust of woman," they bring up a self-evident fact of nature which needs no other inspiration, to show the world that the mother, and not the father, is the true head of the family, and that she should be able to free herself from the adulterous husband, keeping her own body a holy temple for its divine-human uses, of which as priestess and holder of the altar she alone should have control.

— Matilda Joslyn Gage, "A Sermon Against Woman"

Other feminists of the period referred to "voluntary motherhood," achieved through consensual nonprocreative sexual practices, periodic or permanent sexual abstinence, or (most importantly) the right of a woman (especially a wife) to refuse sex.[18]

Works about Native Americans in the United States by Lewis Henry Morgan and Henry Rowe Schoolcraft also influenced Gage. She decried the brutal treatment of Native Americans in her writings and public speeches. She was angered that the Federal government of the United States attempted to impose citizenship upon Native Americans thereby negating their (Iroquois) status as a separate nation and their treaty privileges.

She wrote in 1878:

That the Indians have been oppressed - are now, is true, but the United States has treaties with them, recognising them as distinct political communities, and duty towards them demands not an enforced citizenship but a faithful living up to its obligations on the part of the government.

— Matilda Joslyn Gage, "Indian Citizenship"[19]

In her 1893 work, Woman, Church and State, she cited the Iroquois society, among others, as a 'Matriarchate' in which women had true power, noting that a system of descent through the female line and female property rights led to a more equal relationship between men and women. Gage spent time among the Iroquois and received the name Karonienhawi - "she who holds the sky" - upon her initiation into the Wolf Clan. She was admitted into the Iroquois Council of Matrons.[20]

Family

Gage, who lived at 210 E. Genesee St., Fayetteville, New York, for the majority of her life,[21] had five children with her husband: Charles Henry (who died in infancy), Helen Leslie, Thomas Clarkson, Julia Louise, and Maud.

Maud, who was ten years younger than Julia, initially horrified her mother when she chose to marry author L. Frank Baum (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) at a time when he was a struggling actor with only a handful of plays (of which only The Maid of Arran survives) to his writing credit. However, a few minutes after the initial announcement, Gage started laughing, apparently realizing that her emphasis on all individuals making up their own minds was not lost on her headstrong daughter, who gave up a chance at a law career when the opportunity for women was rare. Gage spent six months of every year with Maud and Frank. Gage's son Thomas Clarkson Gage and his wife Sophia had a daughter named Dorothy Louise Gage, who was born in Bloomington, Illinois, on June 11, 1898, but died five months later, on November 11, 1898.[22]

The death so upset the child's aunt Maud, who had always longed for a daughter, that she required medical attention. Thomas Clarkson Gage's child was the namesake of her uncle Frank Baum's famed fictional character, Dorothy Gale.[22] In 1996, Dr. Sally Roesch Wagner, a biographer of Matilda Joslyn Gage, located young Dorothy's grave in Bloomington. A memorial was erected in the child's memory at her gravesite on May 21, 1997. This child is often mistaken for her cousin of the same name, Dorothy Louise Gage (1883–1889), Helen Leslie (Gage) Gage's child.[22]

Gage died in the Baum home in Chicago, in 1898. Although Gage was cremated, there is a memorial stone at Fayetteville Cemetery that bears her slogan "There is a word sweeter than Mother, Home or Heaven. That word is Liberty."[23]

Her great-granddaughter was U.S. Senator from North Dakota, Jocelyn Burdick.

Matilda effect and legacy

In 1993, scientific historian Margaret W. Rossiter coined the term "Matilda effect", after Matilda Gage, to identify the social situation where woman scientists inaccurately receive less credit for their scientific work than an objective examination of their actual effort would reveal. The "Matilda effect" is the opposite of the "Matthew effect", in which scientists already famous are over-credited with new discoveries.[24] Gage's legacy was detailed in biographies published by Sally Roesch Wagner,[25][26] and Charlotte M. Shapiro.[27]

In 1995, Gage was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[28]

The Gage home in Fayetteville houses (2020) the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation, and is open to the public.[29]

Selected works

| Library resources about Matilda Joslyn Gage |

| By Matilda Joslyn Gage |

|---|

Gage was editor of The National Citizen and Ballot Box, May 1878 - October 1881 (available on microfilm) and as editor of The Liberal Thinker, from 1890 onwards. These publications offered her the opportunity to publish essays and opinion pieces. The following is a partial list.

- "Is Woman Her Own?", published in The Revolution, April 9, 1868, ed. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Parker Pillsbury. pp 215–216.

- "Prospectus", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, ed. Matilda E. J. Gage. May 1878 p 1.

- "Indian Citizenship", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, ed. Matilda E. J. Gage. May 1878 p 2.

- "All The Rights I Want", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, ed. Matilda E. J. Gage. January 1879 p 2.

- "A Sermon Against Woman", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, ed. Matilda E. J. Gage. September 1881 p 2.

- "God in the Constitution", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, ed. Matilda E. J. Gage. October 1881 p 2.[30]

- "What the government exacts", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, ed. Matilda E. J. Gage. October 1881 p 2.[30]

- "Working women", published in The National Citizen and Ballot Box, ed. Matilda E. J. Gage. October 1881 p 3.[30]

- Woman As Inventor, 1870, Fayetteville, NY: F.A. Darling

- History of Woman Suffrage, 1881, Chapters by Cady Stanton, E., Anthony, S.B., Gage, M. E. J., Harper, I.H. (published again in 1985 by Salem NH: Ayer Company)

- The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, 14 and 21 March 1891, editor and editorials. It is possible she wrote some previous unsigned editorials, rather than L. Frank Baum, for whom she completed the paper's run.

- Woman, Church and State, 1893 (published again in 1980 by Watertowne MA: Persephone Press)

References

- Lamphier & Welch 2017, p. 68.

- White 1921, p. 244.

- Gage, Matilda Joslyn (1890). WOMEN’S NATIONAL LIBERAL UNION REPORT OF THE CONVENTION FOR ORGANIZATION.

- "Who Was Matilda Joslyn Gage?". The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19.

- "Susan B. Anthony Institute for Gender & Women's Studies : University of Rochester". www.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Snodgrass 2015.

- Gordon 1990, p. 499.

- Schenken 1999, p. 287.

- Gage, Matilda E. J. (ed). "Prospectus." The National Citizen and Ballot Box. (1878) Vol. 3, No. 2, p.1.

- Gage, Matilda E. J. (ed). "All the Rights I Want." The National Citizen and Ballot Box. (1879) Vol. 3 No. 10, p. 2.

- International Council of Women (1888). "Report of the International Council of Women: Assembled by the National Woman Suffrage Association, Washington, D.C., U.S. of America, March 25 to April 1, 1888" (Public domain ed.). New York: R. H. Darby, printer. p. 347.

- United States. Circuit Court (New York : Northern District). "Speech of Mrs. M. Joslyn Gage," An account of the proceedings on the trial of Susan B. Anthony, on the charge of illegal voting. (1874) Daily Democrat and Chronicle. pp. 179-205.

- Patrick 1996, p. 36.

- Clark 1986, p. 394.

- Harrison 2007, pp. 278-9.

- Hamlin 2014, p. 49.

- Green 1898, p. 337.

- Gordon, Linda (Winter–Spring 1973). "Voluntary Motherhood; The Beginnings of Feminist Birth Control Ideas in the United States". Feminist Studies. 1 (3/4): 5–22. JSTOR 1566477.

- Gage, Matilda E.J. (ed). "Indian Citizenship." The National Citizen and Ballot Box. (1878) Vol. 3, No. 2, p. 2.

- Johansen, Bruce Elliott; Mann, Barbara Alice (2000). Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313308802.

- "Matilda Joslyn Gage Home". Historical Marker Database. 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Willingham, Elaine (1998). “The Story of Dorothy Gage, the Namesake for Dorothy in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz..”, Beyondtherainbow2oz.com; accessed May 20, 2014.

- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=13063718&PIpi=61810911

- Rossiter, Margaret W. (1993). "The Matthew Matilda Effect in Science". Social Studies of Science. 23 (2): 325–341. doi:10.1177/030631293023002004. ISSN 0306-3127. JSTOR 285482.

- Wagner, Sally Roesch (1998). "Matilda Joslyn Gage: She Who Holds the Sky - Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation". www.matildajoslyngage.org. Breakthrough Design Group. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- Wagner 2003, p. 1.

- Shapiro 2013, p. 1.

- National Women's Hall of Fame, Matilda Joslyn Gage

- "The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation". Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- Brammer 2000, p. 126.

Attribution

Bibliography

- Brammer, Leila R. (1 January 2000). Excluded from Suffrage History: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Nineteenth-century American Feminist. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30467-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Elizabeth B. (1986). "Women and Religion in America, 1870–1920". In John Frederick Wilson (ed.). Church and State in America: The Colonial and early national periods. Church and State in America: A Bibliographic Guide. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 394. ISBN 9780313252365.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gordon, Linda (1990). Woman's body, woman's right: birth control in America. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013127-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamlin, Kimberly A. (May 8, 2014). From Eve to Evolution: Darwin, Science, and Women's Rights in Gilded Age America. University of Chicago Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780226134758.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrison, Victoria S. (2007). Religion and Modern Thought. Hymns Ancient and Modern. pp. 278–9. ISBN 9780334041269.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lamphier, Peg A.; Welch, Rosanne (23 January 2017). Women in American History: A Social, Political, and Cultural Encyclopedia and Document Collection [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-603-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patrick, Lucia (1996). Religion and revolution in the thought of Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826–1898). Florida State University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schenken, Suzanne O'Dea (1999). From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics, Volume 1: A-M. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 287. ISBN 0874369606.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shapiro, Charlotte M. (2 March 2013). Searching for Matilda: Portrait of a Forgotten Feminist. Charlotte M. Shapiro. ISBN 978-0-615-77232-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (26 March 2015). The Civil War Era and Reconstruction: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural and Economic History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45791-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wagner, Sally Roesch (2003). The Wonderful Mother of Oz. Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation

- Will of Matilda Joslyn Gage

- Matilda Joslyn Gage papers, 1840-1974. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- "Matilda Joslyn Gage". Social Reformer. Find a Grave. January 18, 2006. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- Works by Matilda Joslyn Gage at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Matilda Joslyn Gage at Internet Archive