Trapping

Animal trapping, or simply trapping, is the use of a device to remotely catch an animal. Animals may be trapped for a variety of purposes, including food, the fur trade, hunting, pest control, and wildlife management.

History

Neolithic hunters, including the members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture of Romania and Ukraine (c. 5500–2750 BC), used traps to capture their prey.[1] An early mention in written form is a passage from the self-titled book by Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi describes Chinese methods used for trapping animals during the 4th century BC. The Zhuangzi reads, "The sleek-furred fox and the elegantly spotted leopard ... can't seem to escape the disaster of nets and traps."[2][3] "Modern" steel jaw-traps were first described in western sources as early as the late 16th century.[4] The first mention comes from Leonard Mascall's book on animal trapping.[5] It reads, "a griping trappe made all of yrne, the lowest barre, and the ring or hoope with two clickets." [sic][6] The mousetrap, with a strong spring device mounted on a wooden base, was first patented by William C. Hooker of Abingdon, Illinois, in 1894.[7][8]

Native Americans trapped fur-bearing animals with pits, deadfalls, and snares. Trapping was widespread in the early days of North American settlements, and companies such as the Canadian fur brigade were established. In the 18th century blacksmiths manually built foothold traps, and by the mid-19th century trap companies manufacturing traps and fur stretchers became established.

The monarchs and trading companies of Europe invested heavily in voyages of exploration. The race was on to establish trading posts with the natives of North America, as trading posts could also function as forts and legitimize territorial claims. The Hudson's Bay Company was one such business. They traded commodities such as flintlock muskets and pistols, knives, food, frying pans, pots, and blankets for furs from trappers and Native Americans.

Trappers and mountain men were the first European men to cross the Great Plains to the Rocky Mountains in search of fur. They traded with Native Americans from whom they learned hunting and trapping skills.

Beaver was one of the main animals of interest to the trappers as the fur wore well in coats and hats. Beaver hats became popular in the early 19th century but later the fashion changed. Towards the end of the century beaver became scarce in many areas and locally extinct in others. The decline in key species of fur-bearers due to over-harvesting, and the later emergence of the first regulatory laws, marked the end of the heyday of unregulated trapping. Many trappers turned to buffalo hunting, serving as scouts for the army or leading wagon trains to the American west. The trails that trappers used to get through the mountains were later used by settlers heading west.

Reasons for trapping

Trapping is carried out for a variety of reasons. Originally, it was for food, fur, and other animal products. Trapping has since been expanded to encompass "pest control", wildlife management, the pet trade, and zoological specimens.

Fur clothing

In the early days of the colonization settlement of North America, the trading of furs was common between the Dutch, French, or English and the indigenous populations inhabiting their respective colonized territories. Many locations where trading took place were referred to as trading posts. Much trading occurred along the Hudson River area in the early 1600s.

In some locations in the US and in many parts of southern and western Europe, trapping generates much controversy as it is seen as a contributing factor to declining populations in some species. One such example is the Canadian Lynx. In the 1970s and 1980s, the threat to lynx from trapping reached a new height when the price for hides rose to as much as $600 each. By the early 1990s, the Canada lynx was a clear candidate for Endangered Species Act (ESA) protection. In response to the lynx’s plight, more than a dozen environmental groups petitioned FWS in 1991 to list lynx in the lower 48 states. Fish and Wildlife Services (FW regional offices and field biologists supported the petition, but FWS officials in the Washington, D.C. headquarters turned it down. In March 2000, the FWS finally listed the lynx as threatened in the lower 48.[9]

In recent years, the prices of fur pelts have declined so low, that some trappers are considering not to trap as the cost of trapping exceeds the return on the furs sold at the end of the season.

Perfume

Beaver castors are used in many perfumes as a sticky substance. Trappers are paid by the government of Ontario to harvest the castor sacs of beavers and are paid from 10–40 dollars per dry pound when sold to the Northern Ontario Fur Trappers Association.

In the early 1900s, muskrat glands were used in making perfume or women just crush the glands and rub them on their body.

Pest control

Trapping is regularly used for pest control of beaver, coyote, raccoon, cougar, bobcat, Virginia opossum, fox, squirrel, rat, mouse and mole in order to limit damage to households, food supplies, farming, ranching, and property.

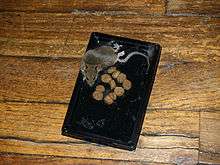

Traps are used as a method of pest control as an alternative to pesticides. Commonly spring traps which holds the animal are used — mousetraps for mice, or the larger rat traps for larger rodents like rats and squirrel. Specific traps are designed for invertebrates such as cockroaches and spiders. Some mousetraps can also double as an insect or universal trap, like the glue traps which catch any small animal that walks upon them.

Though it is common to state that trapping is an effective means of pest control, a counter-example is found in the work of Dr. Jon Way, a biologist in Massachusetts. Dr. Way reported that the death or disappearance of a territorial male coyote can lead to double litters, and postulates a possible resultant increase in coyote density.[10] Coexistence programs that take this scientific research into account are being pursued by groups such as the Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals.

Wildlife management

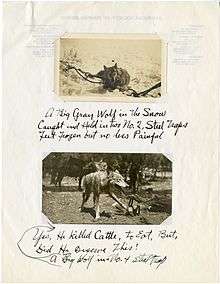

Animals are frequently trapped in many parts of the world to prevent damage to personal property, including the killing of livestock by predatory animals.

Many wildlife biologists support the use of regulated trapping for the sustained harvest of some species of furbearers. Studies have repeatedly shown that trapping can be an effective method of managing or studying furbearers, controlling damage caused by furbearers, and at times reducing the spread of harmful diseases. These studies have shown that regulated trapping is a safe, efficient, and practical means of capturing individual animals without impairing the survival of furbearer populations or damaging the environment.[11] Wildlife biologists also support regulatory and educational programs, research to evaluate trap performance and the implementation of improvements in trapping technology in order to improve animal welfare.[12]

Trapping is useful to control over population of certain species. Trapping is also used for research and relocation of wildlife.[13] Federal authorities in the United States use trapping as the primary means to control predators that prey on endangered species such as the San Joaquin kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica), California least tern (Sterna antillarum browni) and desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii).[14]

Other reasons

Animals may also be trapped for public display, for natural history displays, or for such purposes as obtaining elements used in the practice of traditional medicine. Trapping may also be done for hobby and conservation purposes.

Trap types

Most of the currently used traps used for mammals can be divided into six types: foothold traps, body gripping traps, snares, deadfalls, cages, and glue traps.

Foothold traps

Foothold traps were first invented to keep poachers out of European estates in the 1600s (see Mantrap (snare)). Blacksmiths made traps of iron in the early 1700s for trappers. By the 1800s companies began to manufacture steel foothold traps.

Modified traps are now available with offset jaws, or lamination, or both, which decrease pressure on the animals' legs. Traps are also available with a padded jaw, which has rubber inserts inside the jaws to reduce animal injuries.[15] However these traps may be more expensive. A single number 3 foothold trap which has a 6-inch jaw spread and commonly used for trapping beaver and coyote costs about 10 to 20 dollars depending on the make, while a padded jaw or "Soft Catch" trap may cost from 12 to 20 dollars.[16] Today's traps are specially designed in different sizes for different sized animals, which reduces injuries.[17] Anti-fur campaigns have protested foothold traps claiming that an animal caught in a foothold trap will frequently chew off its leg to escape the trap,[18] while the National Animal Interest Alliance states that modern foothold traps have been designed to hold animals as humanely as possible to reduce incidences of the animal fighting the trap, possibly injuring itself or getting loose in the process.[19]

Some research indicates that in US states that have banned the use of foothold traps, other issues have arisen. In Massachusetts, the beaver population increased from 24,000 in 1996 to over 70,000 beaver in 2001.[20] Coyote attacks on humans rose from 4 to 10 per year, during the five-year period following a 1998 ban on foothold traps in Southern California.[21]

Manufacturers of newer types of traps designed to work only on raccoons are referred to as dog-proof. These traps are small, and rely on the raccoon's grasping nature to trigger the trap. They are sold as coon cuffs, bandit busters and egg traps just to name a few.[22]

Body gripping/conibear traps

.jpg)

Body-gripping traps are designed to kill animals quickly. They are often called "Conibear" traps after Canadian inventor Frank Conibear who began their manufacture in the late 1950s as the Victor-Conibear trap.[23] Many trappers consider these traps to be one of the best trapping innovations of the 20th century;[23][24] when they work as intended, animals that are caught squarely on the neck are killed quickly, and are therefore not left to suffer or given a chance to escape.

The general category of body-gripping traps may include snap-type mouse and rat traps, but the term is more often used to refer to the larger, all-steel traps that are used to catch fur-bearing animals. These larger traps are made from bent round steel bars. These traps come in several sizes including model #110 or #120 at about 5 by 5 inches (130 by 130 mm) for muskrat and mink, model #220 at about 7 by 7 inches (180 by 180 mm) for raccoon and possum, and model #330 at about 10 by 10 inches (250 by 250 mm) for beaver and otter.

An animal may be lured into a body-gripping trap with bait, or the trap may be placed on an animal path to catch the animal as it passes. In any case, it is important that the animal is guided into the correct position before the trap is triggered. The standard trigger is a pair of wires that extend between the jaws of the set trap. The wires may be bent into various shapes, depending on the size and behavior of the target animal. Modified triggers include pans and bait sticks. The trap is designed to close on the neck and/or torso of an animal. When it closes on the neck, it closes the trachea and the blood vessels to the brain, and often fractures the spinal column; the animal loses consciousness within a few seconds and dies soon thereafter. If it closes on the foot, leg, snout, or other part of an animal, the results are less predictable.

Trapping ethics call for precautions to avoid the accidental killing of non-target species (including domestic animals and people) by body-gripping traps.[25][26]

Note on terminology: the term "body-gripping trap" (and its variations including "body gripping", "body-grip", "body grip", etc.) is often used by animal-protection advocates to describe any trap that restrains an animal by holding onto any part of its body. In this sense, the term is defined to include foothold/foothold traps, Conibear-type traps, snares, and cable restraints; it does not include cage traps or box traps that restrain animals solely by containing them inside the cages or boxes without exerting pressure on the animals; it generally does not include suitcase-type traps that restrain animals by containing them inside the cages under pressure.[27][28]

Deadfall traps

A deadfall is a heavy rock or log that is tilted at an angle and held up with sections of branches, with one of them serving as a trigger. When the animal moves the trigger, which may have bait on or near it, the rock or log falls, crushing the animal. The rock or log must be at least five times heavier than the animal that is to be caught. For example, if the target animal is a 3 pound rabbit, the log must be at least 15 pounds.

The figure-four deadfall is a popular and simple trap constructed from materials found in the bush (three sticks with notches cut into them, plus a heavy rock or other heavy object). Also popular, and easier to set, is the Paiute deadfall, consisting of three long sticks, plus a much shorter stick, along with a cord or fiber material taken from the bush to interconnect the much shorter stick (sometimes called catch stick or trigger stick) with one of the longer sticks, plus a rock or other heavy object.[29]

Snares

Snares are anchored cable or wire nooses set to catch wild animals such as squirrels and rabbits.[30] In the USA, they are most commonly used for capture and control of surplus furbearers and especially for food collection. They are also widely used by subsistence and commercial hunters for bushmeat consumption and trade in African forest regions[31] and in Cambodia.[32]

Snares are one of the simplest traps and are very effective.[33] They are cheap to produce and easy to set in large numbers. A snare traps an animal around the neck or the body; a snare consists of a noose made usually by wire or a strong string. Snares are widely criticised by animal welfare groups for their cruelty.[34] UK users of snares accept that over 40% of animals caught in some environments will be non-target animals, although non-target captures range from 21% to 69% depending on the environment.[35] In the USA, non-target catches reported by users of snares in Michigan were 17 +/- 3%.[36]

Snares are regulated in many jurisdictions, but are illegal in other jurisdictions, such as in much of Europe. Different regulations apply to snares in those areas where they are legal. In Iowa, snares have to have a 'deer stop' which stops a snare from closing all the way. In the United Kingdom, snares must be 'free-running' so that they can relax once an animal stops pulling, thereby allowing the trapper to decide whether to kill[37][38] the animal or release it. Following a consultation on options to ban or regulate the use of snares,[39] the Scottish Executive announced a series of measures on the use of snares, such as the compulsory fitting of safety stops, ID tags and marking areas where snaring takes place with signs.[40] In some jurisdictions, swivels on snares are required, and dragging (non-fixed) anchors are prohibited.[41][42]

Trapping pit

Trapping pits are deep pits dug into the ground, or built from stone, in order to trap animals. Like cage traps they are usually employed for catching animals without harming them.

Cage traps (live traps)

Cage traps are designed to catch live animals in a cage. They are usually baited, sometimes with food bait and sometimes with a live "lure" animal. Common baits include cat food and fish. Cage traps usually have a trigger located in the back of the cage that causes a door to shut; some traps with two doors have a trigger in the middle of the cage that causes both doors to shut. In either type of cage, the closure of the doors and the falling of a lock mechanism prevents the animal from escaping by locking the door(s) shut.

Supporters of cage traps say that they are the most humane form of trapping, and in some countries are the only method of trapping allowed. Cage traps are used by animal control officers to catch unwanted animals and move them to another location without harm, as well as by gamekeepers to catch birds and animals they consider to be pests.

Cage traps are also sometimes used for capturing small animals such as squirrels by homeowners in attics or basements of homes, for removal to locations where they may either be legally killed and disposed of, or released unharmed. Some municipal jurisdictions specifically prohibit transporting live squirrels and releasing them into other areas to control the spread of diseases; for these jurisdictions, killing the squirrels within the cage quickly and humanely is the only legal means of disposing of them.

Cage traps are also used in muskrat trapping. A cage trap is set in a runway and the muskrat pushes the door open which is at a 45 degrees. Once the muskrat enters the cage trap the other side is closed with another door at 45 degrees. The muskrat drowns in the trap which is set under water. No bait is necessary, as the trap is set in a muskrat runway.

In the UK, cage traps are used to control corvids and such trapping is mainly carried out on game shooting estates. Large ladder traps and smaller Larsen traps are used.

Large heavy-duty cage traps are also useful in catching large dangerous animals for transport and are a favourite of Australian crocodile trappers. Due to their bulk and cost, they are hard to set in great numbers or in remote locations.

Cage-trapping squirrels

One manufacturer says that their customers reported more success when using double door cage traps. With two doors open, the squirrel can see through the opening on the opposite end. Peanut butter is placed in the trap as bait to attract the squirrel.

In some locations, the traps can be placed in alignment with a building, wall, or fence (nearly under one edge of a bush). The wall does not present a threat to the squirrel, and the bush reduces the exposure and view of the squirrel. A blind area (by using natural or cardboard materials) surrounding the end of the trap presents a darker, safe hiding space near the trigger and bait of the trap. Where two-door traps are not available, a piece of cardboard held in place with a brick can be put behind the rear of the trap.

Glue traps

Glue traps (also called adhesive or sticky traps) are made using adhesive applied to cardboard or similar material. Bait can be placed in the center or a scent may be added to the adhesive; alternatively, the traps may be placed in animal pathways.[43] Glue board traps are used primarily for rodent and insect control indoors. Glue traps are not effective outdoors because environmental conditions (moisture, dust) quickly make the adhesive ineffective.

Domestic animals accidentally captured in glue traps can be released by carefully applying cooking oil or baby oil to the contact areas and gently worked until the animal is free. Many animal rights groups, such as the Humane Society and In Defense of Animals, oppose the use of glue traps for their cruelty to animals.[44][45]

Types of sets

The most productive set for foothold traps is a dirt hole, a hole dug in the ground with a trap positioned in front. An attractant is placed inside the hole. The hole for the set is usually made in front of some type of object which is where medium-sized animals such as coyotes, fox or bobcats would use for themselves to store food. This object could be a tuft of taller grass, a stone, a stump, or some other natural object. The dirt from the hole is sifted over the trap and a lure applied around the hole.

A flat set is another common use of the foothold trap. It is very similar to the dirt hole trap set, simply with no hole to dig. The attractant is placed on the object near the trap and a urine scent sprayed to the object.

The cubby set simulates a den in which a small animal would live, but could be adapted for larger game. It could be made from various materials such as rocks, logs or bark, but the back must be closed to control the animals approach. The bait and/or lure is placed in the back of the cubby.

The water set is usually described as a body-gripping trap or snare set so that the trap jaws or snare loop are partially submerged. The conibear is a type of trap used in water trapping and can also be used on land and is heavily regulated. The regulations vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. It is normally used without bait and has a wire trigger in the middle of its square-shaped, heavy-gauge wire jaws. It is placed in places that are frequented by the fur bearing animals.

Unwanted catches

Trappers can employ a variety of devices and strategies to avoid unwanted catches. Ideally, if a non-target animal (such as a domestic cat or dog) is caught in a non-lethal trap, it can be released without harm. A careful choice of set and lure may help to catch target animals while avoiding non-target animals. Although trappers cannot always guarantee that unwanted animals won't be caught, they can take precautions to avoid unwanted catches or release them unharmed.

The snaring of non-target animals can be minimized using methods that exclude animals larger or smaller than the target animal. For example, deer stops are designed to avoid the snaring of deer or cattle by the leg; they are required in some parts of the USA.[46] Other precautions include setting snares at specific heights, diameters, and locations. In a study of foxes in the UK, researchers were unintentionally snaring brown hares about as frequently as the intended foxes until they improved their methods, using larger wire with rabbit stops to eliminate the unwanted catch of the brown hares.[47]

Controversy

Any type of trap—whether it be a foothold/leghold, conibear, or snare/cable restraint—can get an unwanted catch.[48] Both endangered species and domestic pets have been injured or killed by illegally set traps. For example, in December 2012 a Golden Retriever dog was killed when walking with his owner on a trail in the woods of Auburn, New Hampshire.[49] The dog became ensnared in an illegally placed conibear trap and was suffocated, despite his owner's best attempts to free him. It has been estimated by Wildlife Services, a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, that over the last decade, hundreds of pets have been killed by body-gripping traps, and that the agency itself has killed thousands of non-target animals in several states, from pet dogs to endangered species.[50] The number of non-target animals killed has caused national and regional animal-protection organizations such as the Humane Society of the United States, American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and others to continue to lobby for stricter controls over the use of these traps in the United States.

Trapping might lead to stress, pain, or even in some cases death for the animal, depending on the type of trap. Traps that work by catching limbs can occasionally cause injuries on the limbs, especially if used improperly, and the animal is left unattended until the trapper comes by, and might die e.g. from the injury, starvation or attacks from other animals. Many states employ the regulation that a trap must be checked at least every 36 hours to minimize risks to the animals.

Trapping requires time, hard work and money but can be very efficient. Trapping has become expensive for the trapper, and in modern times it has become controversial. In part to address these concerns, in 1996, the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, an organization made up of state and federal fish and wildlife agency professionals, began testing traps and compiling recommendations "to improve and modernize the technology of trapping through scientific research" known as Best Management Practices.[51] As of February 2013, twenty best management practice recommendations have been published, covering nineteen species of common furbearers across North America.[52]

See also

- Animal population control

- Bird trapping

- Bottle trap

- Bushmeat

- Cannon netting

- Crab trap

- Fish trap

- Fly-killing device

- Game Warden

- Hunting

- Insect collecting

- Lobster trap

- Malaise trap

- Mouse Trap

- Ornithology

- Pitfall trap

- Rocket net

- Trapping pit

References

- Cucoș, Ștefan. Faza Cucuteni B în zona subcarpatică a Moldovei (in Romanian). Archaeology Museum Piatra Neamț, 1999

- Zhuangzi (translated by Burton Watson). The Complete Works of Zhuang Zi. New York: Columbia University Press, 1968 (ISBN 0-231-03147-5), pp. 20–21

- Chinese: 道:"丰狐,文豹……不免于网罗机辟之患"

- "Natural History of Beavers". Archived from the original on 2010-02-26. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- Considine, John. "Mascall, Leonard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18256. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- Mascall, Leonard. A Book of Fishing with Hook and Line: Another of Sundrie Engines and Trappes to take Polecats, Buzzards, Rates, 1590.

- Patent of William C. Hooker's animal-trap in Google Patents.

- "United States Patents: New York State Library". nysed.gov. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- "Canada Lynx". Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "research" (PDF).

- "Principles of Wildlife Management in Montana".

- "Joomla.wildlife.org" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- "Trapping for Research and Reintroduction". Anr.state.vt.us. Archived from the original on 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- "Digitalcommons.unl.edu". Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- "Digitalcommons.unl.edu". Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- R-P outdoors Fall/Winter 2008-2009 catalog

- "Association of Fish&Wildlife Agencies". Fishwildlife.org. Archived from the original on 2009-09-05. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- "Coalition to Abolish the Fur Trade". Caft.org.uk. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- Stephen Vantassel (2009). "Animal Rights Activists Gloss Over Trapping Facts". Naiaonline.org. Archived from the original on 2009-06-29. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (2007-09-20). "MassWildlife - Managing Beaver". Mass.gov. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- Coolahan, Craig C.; Bennett, Joe R.; Baker, Rex O.; Timm, Robert M. (2004-03-03). "Coyote Attacks: An Increasing Suburban Problem". Repositories.cdlib.org. Retrieved 2009-06-15. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "NTA - Trapping Facts". Nationaltrappers.com. 2002-09-15. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- Bevington, Angie (December 1983). "Arctic Profiles: Frank Ralph Conibear (1896-)" (PDF). Arctic. 36 (4): 386–387. doi:10.14430/arctic2301. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Collier, Eric (1957-10-01). "Revolutionary new trap, parts I and II". Outdoor Life. 1957 (Sept. and Oct): Sept: 38–41, 68, 80. Oct: 70–73, 80, 82.

- "Trapping Ethics". Minnesota Trappers Association. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Minnesota Trapper Education Manual (PDF). Minnesota Trappers Association and Minnesota DNR. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-17. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- Booker, Cory A.; Lowey, Nita M. (2015-05-06). "Refuge from Cruel Trapping Act". Congress.gov. U.S. Congress. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- Born Free USA, Legal and Government Affairs Department. "Born Free USA's Expertise in Trapping: A Resource for Legislators". Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- U.S. Army (June 1992). "Food Procurement (Chapter 8)" (PDF). U.S. Army Survival Manual FM 21-76. U.S. Army. pp. 8–19, 8–20.

- James Kirkwood (August 2005). "Report of the Independent Working Group on Snares" (PDF). Defra. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2013-02-25.

- Noss, Andrew J. (2002-05-10). "CJO - Abstract - Cable snares and bushmeat markets in a central African forest". Environmental Conservation. 25 (3): 228–233. doi:10.1017/S0376892998000289.

- Hance, Jeremy (2018-05-22). "Rangers find 109,217 snares in a single park in Cambodia". The Guardian.

- Andelt, William F. (1993). Publication No. 6.517 Proper use of snares for capturing furbearers (PDF). Colorado State University Cooperative Extension. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- "League Against Cruel Sports : Snaring". League.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-11-15. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- James Kirkwood (August 2005). "Report of the Independent Working Group on Snares" (PDF). Defra. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-10. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- "Michigan.gov" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- "Canadian Wildlife Federation :: The Canadian Wildlife Federation". Spaceforspecies.ca. Archived from the original on 2008-02-14. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- "Governance By-law Samples: Sample Hunting By-law". Ainc-inac.gc.ca. 2008-11-03. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- "Scotland.gov.uk" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- "UK | Scotland | Ministers reject snare ban plea". BBC News. 2008-02-20. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- "Wisconsin Cable Restraints and Snare Regulations" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- "Michigan Fox & Coyote Non-Lethal Snaring Guide" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- Chapple, David (2016-10-05). New Zealand Lizards. Springer. ISBN 9783319416748.

- "Glue Traps: FAQs". September 22, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- "Glue Boards". humanesociety.org. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies Furbearer Conservation Technical Work Group (2009). "Modern Snares for Capturing Mammals: Definitions, Mechanical Attributes and Use Considerations" (PDF). Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

- Kirkwood, James K; Working Group (2005). "Report of the Independent Working Group on Snares" (PDF). UK Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). p. 54 (section 2.7). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- "Non-Target Trapping Incidents in the United States". Born Free USA. Archived from the original on 2013-06-01. Retrieved 2013-05-17.

- Clogston, Brendan (December 7, 2012). "Illegal hunting trap suffocates retriever". New Hampshire Union Leader. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- Corbin, Cristina (March 17, 2013). "Hundreds of family pets, protected species killed by little known federal agency". FoxNews.com. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

- "Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies Introduction to BMPs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- "The Voice of Fish & Wildlife Agencies". jjcdev.com. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

External links

![]()

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 212–213.

- How to do Trap, Neuter, Return: using humane cat traps Stray Cat Alliance

- Camp Life in the Woods and the Tricks of Trapping and Trap Making by William Hamilton Gibson, from Project Gutenberg

- Traps and Snares Collection

- Wildwood Survival: How to construct a Figure-4 deadfall trap

- Joint Industry Briefing: The importance of snaring (Scotland)

- How To Make a Snare: Survival Education by Hemming Outdoors