Tucumcari, New Mexico

Tucumcari (pronounced TOO-cum-carry) is a city in and the county seat of Quay County, New Mexico, United States.[3] The population was 5,363 at the 2010 census. Tucumcari was founded in 1901, two years before Quay County was founded.[4]

Tucumcari, New Mexico | |

|---|---|

Quay County Courthouse in 2008 | |

Seal | |

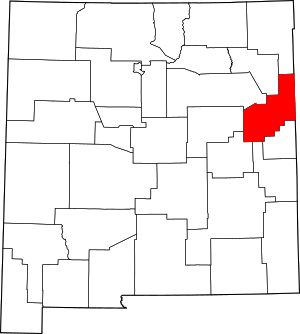

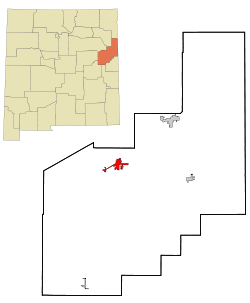

Location of Tucumcari in New Mexico | |

Tucumcari, New Mexico Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 35°10′10″N 103°43′32″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Mexico |

| County | Quay |

| Founded | 1901 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ruth Ann Litchfield |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.51 sq mi (24.63 km2) |

| • Land | 9.51 sq mi (24.62 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,091 ft (1,247 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 5,363 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 4,867 |

| • Density | 511.94/sq mi (197.65/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code | 88401 |

| Area code(s) | 575 |

| FIPS code | 35-79910 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0915909 |

| Website | City Website |

History

In 1901, the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad built a construction camp in the western portion of modern-day Quay County. Originally called Ragtown, the camp became known as Six Shooter Siding, due to numerous gunfights. Its first formal name, Douglas, was used only for a short time.[5] After it grew into a permanent settlement, it was renamed Tucumcari in 1908. The name was taken from Tucumcari Mountain, which is situated near the community.[6] Where the mountain got its name is uncertain. It may have come from the Comanche word tʉkamʉkarʉ, which means 'ambush'.[7] A 1777 burial record mentions a Comanche woman and her child captured in a battle at Cuchuncari, which is believed to be an early version of the name Tucumcari.[5][8]

In December 1951, a water storage tank collapsed in the city. Four were killed and numerous buildings were destroyed.

Geography

Tucumcari is located at 35°10′10″N 103°43′32″W (35.169453, −103.725488).[9] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.6 sq mi (19.6 km2), of which, 7.5 sq mi (19.5 km2) of it is land and 0.13% is water.

Climate

Tucumcari has a cool semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk) characterized by cool winters and hot summers. Rainfall is relatively low except during the summer months, when thunderstorms associated with the North American monsoon can bring locally heavy downpours. Snowfall is generally light, with a mean of 19.4 inches or 0.49 metres and a median of 9.7 inches or 0.25 metres. Due to the frequency of low humidity, wide daily temperature ranges are normal.

The record high temperature at Tucumcari was 110 °F (43 °C) on July 13, 2020, and the record low temperature −22 °F (−30 °C) on January 13, 1963. The hottest monthly mean maximum has been 100.5 °F or 38.1 °C in July 2011 and the coldest mean minimum 12.4 °F or −10.9 °C in January 1963, although the coldest month by mean maximum was January 1949 with a mean high of 38.6 °F or 3.7 °C.[10]

The wettest calendar year has been 1941 with 34.94 inches (887.5 mm) and the driest 1934 with 6.13 inches (155.7 mm).[10] The most rainfall in one month was 11.19 inches (284.2 mm) in July 1950. The most rainfall in 24 hours was 4.41 inches (112.0 mm) on June 21, 1971. The most snowfall in one year was 46.7 inches (1.19 m) in from July 1918 to June 1919. The most snowfall in one month was 30.0 inches (0.76 m) in February 1912.[10]

| Climate data for Tucumcari 4 NE (1971-2000; extremes 1904-2001) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

83 (28) |

92 (33) |

97 (36) |

103 (39) |

109 (43) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

97 (36) |

87 (31) |

82 (28) |

109 (43) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 52.7 (11.5) |

57.6 (14.2) |

65 (18) |

72.4 (22.4) |

80.9 (27.2) |

89.9 (32.2) |

93 (34) |

90.7 (32.6) |

83.9 (28.8) |

74.3 (23.5) |

61.5 (16.4) |

53 (12) |

72.9 (22.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 22.9 (−5.1) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

33.9 (1.1) |

41.5 (5.3) |

51.2 (10.7) |

60.2 (15.7) |

64.3 (17.9) |

62.7 (17.1) |

55.2 (12.9) |

44 (7) |

32.4 (0.2) |

24.2 (−4.3) |

43.3 (6.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−16 (−27) |

−3 (−19) |

14 (−10) |

25 (−4) |

37 (3) |

52 (11) |

49 (9) |

30 (−1) |

12 (−11) |

−2 (−19) |

−12 (−24) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.41 (10) |

0.43 (11) |

0.81 (21) |

1.12 (28) |

1.84 (47) |

2.19 (56) |

2.64 (67) |

2.73 (69) |

1.68 (43) |

1.44 (37) |

0.75 (19) |

0.53 (13) |

16.57 (421) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.2 (13) |

3.5 (8.9) |

1.9 (4.8) |

1.6 (4.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

1.7 (4.3) |

5.1 (13) |

19.4 (49.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 8.8 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 60.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 inch) | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1 | 2.3 | 9 |

| Source: [11] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 2,526 | — | |

| 1920 | 3,117 | 23.4% | |

| 1930 | 4,143 | 32.9% | |

| 1940 | 6,194 | 49.5% | |

| 1950 | 8,419 | 35.9% | |

| 1960 | 8,143 | −3.3% | |

| 1970 | 7,189 | −11.7% | |

| 1980 | 6,765 | −5.9% | |

| 1990 | 6,831 | 1.0% | |

| 2000 | 5,989 | −12.3% | |

| 2010 | 5,363 | −10.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 4,867 | [2] | −9.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

As of the census[13] of 2000, there were 5,989 people, 2,489 households, and 1,607 families residing in the city. The population density was 793.8 people per square mile (306.7/km2). There were 3,065 housing units at an average density of 406.2 per square mile (156.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 75.87% White, 1.29% African American, 1.39% Native American, 1.20% Asian, 0.22% Pacific Islander, 17.10% from other races, and 2.94% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 51.41% of the population.

There were 2,489 households out of which 29.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.4% were married couples living together, 15.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.4% were non-families. 31.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 2.93.

In the city, the population was spread out with 26.0% under the age of 18, 7.5% from 18 to 24, 24.2% from 25 to 44, 24.8% from 45 to 64, and 17.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.8 males.

Economy

The median income for a household in the city was $22,560, and the median income for a family was $27,468. Males had a median income of $25,342 versus $18,568 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,786. About 19.1% of families and 24.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.5% of those under age 18 and 16.7% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Schools in Tucumcari cover all groups from daycare to post-secondary education.

- Tucumcari Early Head Start and Head Start (non-public daycare and preschool)

- Tucumcari Elementary School (public Pre-K through fifth grade)

- Tucumcari Middle School (public sixth grade through eighth grade)

- Tucumcari High School (public ninth grade through twelfth grade)

- Mesalands Community College (community two-year institution of higher learning)

Legend surrounding the area

Legend has it that Apache Chief Wautonomah was nearing the end of his time on earth and was troubled by the question of who would succeed him as ruler of the tribe. In a classic portrait of love and competition, his two finest braves, Tonopah and Tocom, not only were rivals and sworn enemies of one another, but were both vying for the hand of Kari, Chief Wautonomah's daughter. Kari knew her heart belonged to Tocom. Chief Wautonomah beckoned Tonopah and Tocom to his side and announced, "Soon I must die and one of you must succeed me as chief. Tonight you must take your long knives and meet in combat to settle the matter between you. He who survives shall be the Chief and have for his wife Kari, my daughter."

As ordered, the two braves met, with knives outstretched, in mortal combat. Unknown to either brave was that Kari was hiding nearby. When Tonopah's knife found the heart of Tocom, the young woman rushed from her hiding place and used a knife to take Tonopah's life as well as her own.

When Chief Wautonomah was shown this tragic scene, heartbreak enveloped him and he buried his daughter's knife deep into his own heart, crying out in agony, "Tocom-Kari"!

A slight variation of the Chief's dying words lives on today as Tucumcari, and the mountain that bears this name stands as a stark reminder of unfulfilled love.

Some credit this folk tale to Geronimo. Others, believing the claims to be apocryphal, purport the tale variously to have been concocted by anyone from a 1907 Methodist minister[14] to a group of local businesspeople seated together at the old Elk Drugstore each embellishing the stories one by one.[15] Nonetheless, the town is named for Tucumcari Mountain, which in turn takes its name from native origins.

Gelo has documented another origin of the name, reportedly from a Comanche when the first train arrived. He stated "tuka? manooril, carry the light!"; to a brakeman with a lantern. The brakeman repeated this as "'tukama ... carry' [i.e., Tucumcari], that will be the name of this town."[16]

Perhaps the most credible source for the name, and certainly the earliest, is found in the diary of Pedro Vial. His diary published in 1794 mentions travel past "Tuconcari", known today as Tucumcari Mountain.[17]

In popular culture

- Many of the scenes in the television show Rawhide (1959–1966) starring Clint Eastwood were shot in the Tucumcari area.[18]

- One of the killers in Truman Capote's 1965 book In Cold Blood asks about the travelling distance to Tucumcari. This scene appears in the 1967 film version of the novel.

- Tucumcari is the setting of one of the first scenes in Sergio Leone's 1965 film For a Few Dollars More, starring Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef, and Gian Maria Volonté. However, this is a prochronism, as Tucumcari was founded many years after the historical period in which For a Few Dollars More takes place.

- A scene in the 1971 movie Two-Lane Blacktop, starring James Taylor, Dennis Wilson, and Warren Oates, was filmed at a gasoline service station on U.S. Highway 54 just northeast of Tucumcari. Tucumcari Mountain is clearly visible at the beginning of this scene.

- In the David Stone Series featuring Micah Dalton, the lead character was raised in Tucumcari.[19]

- Scenes for the film, Hell or High Water, were filmed in Tucumcari on June 1, 2015.[20]

- A segment of the 2018 movie The Ballad of Buster Scruggs centers around an unsuccessful attempt to rob a bank in Tucumcari.

- The song "Willin'" by Little Feat mentions the city in the lyrics, the line being "I've been from Tucson to Tucumcari; Tehachapi to Tonopah."

- A plot strand in series 5 of AMC’s Better Call Saul, the prequel to Breaking Bad, revolves around legal battles to oust a resident from their house near Tucumcari so that Mesa Verde, Kim’s client, can build a call centre there.

Tucumcari Tonite, Route 66, and tourism

For many years, Tucumcari has been a popular stop for cross-country travelers on Interstate 40 (formerly U.S. Route 66 in the area). It is the largest city on the highway between Amarillo, Texas and Albuquerque, New Mexico. Billboards reading "TUCUMCARI TONITE!" placed along I-40 for many miles to the east and west of the town invite motorists to stay the night in one of Tucumcari's "2000" (later changed to "1200") motel rooms. The "TUCUMCARI TONITE!" campaign was abandoned in favor of a campaign which declared Tucumcari, "Gateway to the West". However, on June 24, 2008, Tucumcari's Lodgers Tax Advisory Board, the group responsible for the billboards, voted to return to the previous slogan.[21]

Old U.S. Route 66 runs through the heart of Tucumcari via Route 66 Boulevard, which was previously known as Tucumcari Boulevard from 1970 to 2003 and as Gaynell Avenue before that time. Numerous businesses, including gasoline service stations, restaurants, and motels, were constructed to accommodate tourists as they traveled through on the Mother Road. A large number of the vintage motels and restaurants built in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s are still in business despite intense competition from newer chain motels and restaurants in the vicinity of Interstate 40, which passes through the city's outskirts on the south.

Tucumcari is the home of over 50 murals. Most were painted by artists Doug and Sharon Quarles and serve as a tourist attraction.[22]

Former railroad transit point

Tucumcari until the mid-twentieth century was a junction for transcontinental train service. The Rock Island Railroad ran pool train operations with the Southern Pacific, with transfers at the station (for the Tucumcari-Los Angeles leg of the trip). The Choctaw Rocket (Memphis-Little Rock-Tucumcari-El Paso-Los Angeles) made the switch there (for the coach cars). The Golden State (Chicago-Kansas City-Topeka-Tucumcari-El Paso-Los Angeles) ran continuous through the town.

Historic Downtown

Most of Tucumcari's oldest buildings lie along or near Main Street in the Historic Downtown area. These include:

- Rock Island-Southern Pacific Train Station (built 1926, restored 2011)

- Odeon Theatre (built 1937, still operating)

- Crescent Creamery (vacant)

- Masonic Temple (still operating)

- Princess Theater (under renovation)

Also located in the downtown area are the concrete arches that once surrounded the Hotel Vorenburg, which was demolished in the 1970s after being damaged by fire. The Federal Building, commonly known as Sands-Dorsey Drug, was damaged by two fires before finally being demolished in 2015. The location is now a park.[23][24]

USS Tucumcari

The city had a United States Navy hydrofoil named after it. The USS Tucumcari (PGH-2) was built by Boeing. It began service in 1968 and ended service in 1972 after running aground in Puerto Rico.

Events

The buildings formerly at Metropolitan Park (locally known as "Five Mile Park" because it is located about five miles (8 km) outside of town) were designed by Trent Thomas, adapted from his design of La Fonda Hotel in Santa Fe. The park once featured New Mexico's largest outdoor swimming pool. Owing to deterioration, Metropolitan Park was named to the New Mexico Heritage Preservation Alliance's list of Most Endangered for 2003.[25] In 2010, the park's main building caught fire and burnt to the ground. The city of Tucumcari razed the site weeks after the fire.[26]

In 2014, a series of suspicious fires destroyed abandoned buildings, including the Tucumcari Motel, Payless Motel, and a house in the 500 block of North Fourth Street. A former Tucumcari Police Department officer and several others have been charged with arson.[27][28][29]

The town formerly hosted an air show each year. The show held on October 4, 2006, was canceled after one hour when a single-engine plane crashed, resulting in the pilot's death.[30]

Notable people

- In 1896, Tom "Black Jack" Ketchum and his associates robbed a post office and store in Liberty, NM, a community that dissolved after the railroad bypassed it. Many of Liberty's residents moved to the nearby railroad siding that eventually became Tucumcari. Some of the local residents believe that there is a cave in a mesa south of Tucumcari, which may hold some loot, from the robbery of Liberty, New Mexico.[31]

- Musician Bob Scobey was born in Tucumcari in 1916.[32]

- American character actor Paul Brinegar was born in Tucumcari.[33]

- Tucumcari High School graduate Stan David was a star safety for the Texas Tech Red Raiders and played 16 NFL games for the Buffalo Bills in 1984. He was listed as number 48 in the Sports Illustrated list of "The 50 Greatest New Mexico Sports Figures."[34]

- Rex Maddaford, who competed for the New Zealand team in the 1968 Summer Olympics, has been a long-time Tucumcari Public Schools faculty member.[35]

See also

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Request Rejected". www.usbr.gov. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Tucumcari". New Mexico Office of the State Historian. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- "Photo Guide:T". Southwest Collection Library. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- Lila Wistrand-Robinson & James Armagost. Comanche Dictionary and Grammar, 2nd edition (2012, Summer Institute of Linguistics).

- "Cuchuncari", however, is from Old Comanche kuhtsunkarɨ 'buffalo sitting'.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- Albuquerque National Weather Service; NOW Data

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Climatography of the United States No. 20: 1971-2000; TUCUMCARI 4 NE, NM

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Lowe, Sam (January 2009). New Mexico Curiosities: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff. Globe Pequot. ISBN 9780762746705.

- Dan Kenneth Phillips. "Four Corners - A Literary Excursion Across America".

- Gelo, Daniel J. (2000). ""Comanche Land and Ever Has Been": A Native Geography of the Nineteenth-Century Comanchería". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 103 (3): 273–307. JSTOR 30239220.

- Vial, Pedro. "Diary of Pedro Vial". Pedro de Nava to the Conde de Revilla Gigedo, Viceroy of Mexico. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Domain Inquiry". jcgi.pathfinder.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Google Books: The Echelon Vendetta

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved 2016-05-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "'Tucumcari Tonite' Returns to Billboards". Albuquerque Journal. June 25, 2008.

- "New Mexico couple's murals helping bring tourists to their town". KRQE. February 6, 2019. Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- "Sands-Dorsey building collapses under fire". Quay County Sun. 2012-05-08. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- "City acquires the Sands Dorsey building for demolition". Quay County Sun. 2015-07-28. Archived from the original on 2016-07-01. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- NMHeritage.org: Resources: NM Preservation Resources Archived 2007-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-01-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-21. Retrieved 2014-10-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-15. Retrieved 2014-10-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-14. Retrieved 2014-10-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fatal accident at air show : News : KVII Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Black Jack Ketchum

- "Yahoo!". www.mmguide.musicmatch.com. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Wilson, Earl (Nov 27, 1969). "Small Towns Have Produced Many Big Stars". The Milwaukee Sentinel. pp. A33. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- "SI.com - SI 50th - New Mexico - The 50 Greatest New Mexico Sports Figures - Wednesday July 09, 2003 04:11 PM". CNN.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2006-09-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tucumcari, New Mexico. |

- City of Tucumcari

- Tucumcari Chamber of Commerce