Eva Emery Dye

Eva Emery Dye (1855 – February 25, 1947) was an American writer, historian, and prominent member of the Women's Suffrage movement. As the author of several historical novels, fictional yet thoroughly researched, she is credited with "romanticizing the historic West, turning it into a poetic epic of expanding civilization."[2] Her best known work, The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis & Clark (1902), is notable for being the first to present Sacagawea as a historically significant character in her own right.

Eva Emery Dye | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1855 Prophetstown, Illinois, US |

| Died | February 25, 1947 (aged 91–92) [1] Oregon City, Oregon, US |

| Occupation | writer, historian, activist |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Spouse | Charles Henry Dye |

Early life

Born Eva Lucinda Emery, the daughter of Cyrus and Caroline Trafton Emery, in Prophetstown, Illinois, she first attracted notice at the age of fifteen, when she began writing poems under the pseudonym "Jennie Juniper". These works, published first in the local Prophetstown Spike then in other regional newspapers, fueled an ambition for intellectual achievement that was unsupported by her family. When her father opposed her seeking a college education, she worked as a school teacher and saved the funds to attend Oberlin College independently.

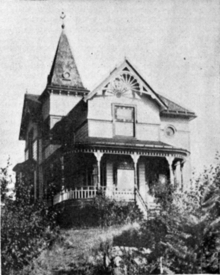

Graduating in 1882, Emery married Charles Henry Dye, a fellow Oberlin alumnus, that same year. Although she had been named Poet Laureate of her class, her writing career was dormant until 1890, when the Dyes made the decision to move to Oregon City, Oregon. Arriving the following year, the couple quickly rose to both wealth and local prominence, with Charles Dye prospering as a lawyer and real estate investor. Dye promptly began what would prove to be her life's work, the chronicling of the early history of the Pacific Northwest. As she later commented, "I began writing as soon as I reached this old and romantic historical city. I saw beautiful historical material lying around like nuggets." [3]

Literary career

"At the turn of the [20th] century Eva Emery Dye replaced [Frances Fuller] Victor as Oregon's best-known historical researcher," wrote Richard Etulain in 2001. "But Dye turned her prodigious findings toward other ends, producing several works of historical fiction."[4]

Writing in a style later described as "a curious blend of fact, fiction, biography, and romance,"[5] Dye first completed McLoughlin and Old Oregon (1900), a portrait of Doctor John McLoughlin 1784–1857, the former Chief Factor of the Columbia District and for years the de facto leader of the Oregon Country. While taking considerable liberties with its subject (including imagined scenes and invented dialogue), the work was nevertheless based upon considerable research, including extensive interviews with aged pioneers who had known McLoughlin personally. The book's popular success established Dye as an author, and contributed to the posthumous re-evaluation of McLoughlin's complex role in American history. Dye and her husband also interceded when McLoughlin's house in Oregon City was slated for destruction, leading the effort to purchase it and restore it as a museum in 1910. It is now part of the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

"Discovery" of Sacagawea

Dye then began researching the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which had reached the Pacific Northwest in 1805. Her subsequent book The Conquest was loosely a joint biography of William Clark and his brother George Rogers Clark (who did not accompany the expedition), yet it was soon lauded for its vivid portrayal of a personage who had played only a minor role in earlier narratives.

Reliable historical information about Sacagawea is extremely limited; even the correct spelling of her name (Lewis and Clark rendered it eight different ways) and the date of her death are under dispute. As the Oregon History Project observes:

The Expedition journals make note of her service as an interpreter and mention that she pointed out familiar landmarks when they entered Shoshone territory. There is little evidence to suggest, however, that she acted as the Expedition’s guide beyond recognizing Bozeman Pass as a good place to cross the Continental Divide.[6]

While her previous book included fictional stylistic elements but conformed on a narrative level to known facts, The Conquest was notably unfettered by adherence to the historical record. Dye's portrayal of Sacagawea ascribed to her imagined features (no portrait or description survives), and postulated that her role was integral to the expedition's success, to the extent that she should be commemorated equally with Lewis and Clark:

Sacajawea's hair was neatly braided, her nose was fine and straight, and her skin pure copper like a statue in some Florentine gallery. Madonna of her race, she had led the way to a new time. To the hands of this girl, not yet eighteen, had been entrusted the key that unlocked the road to Asia...Some day, upon the Bozeman Pass, Sacajawea's statue will stand beside that of Clark. Some day where the rivers part, her laurels will view with those of Lewis. Across North America a Shoshone Indian princess touched hands with Jefferson, opening her country.[7]

The book became an immediate popular success. As Dye herself recalled:

The world snatched at my heroine, Sacajawea...The beauty of that faithful Indian woman with her baby on her back, leading those stalwart mountaineers and explorers through the strange land appealed to the world.[8]

Suffrage

The book's popularity also brought political ramifications. As Dye noted in her book, Sacagawea had been given a vote in a key decision of the expedition: whether or not to build Fort Clatsop and spend the winter on the Pacific coast. This led to "the Madonna of her race" being championed as a symbol of the burgeoning women's suffrage movement, which Dye enthusiastically supported. In keeping with her book's suggestion of a memorial to Sacagawea, a Statue Association was founded in Portland, Oregon, with Dye serving as its president. In this capacity she issued appeals to women's groups across the country, and coordinated the fundraising sale of commemorative "Sacajawea spoons" and "Sacajawea buttons."

In 1905 The National American Woman's Suffrage Association, convening in Portland, unveiled a statue, Sacajawea and Jean-Baptiste, by sculptor Alice Cooper of Denver. In her opening address, Susan B. Anthony remarked:

This is the first time in history that a statue has been erected in memory of a woman who accomplished patriotic deeds... This recognition of the assistance rendered by a woman in the discovery of this great section of the country is but the beginning of what is due...[9]

Following the ceremony, Dye formally presented the statue to the soon-to-open Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, where it was seen by an estimated three million visitors. It currently resides in Portland's Washington Park at 45.521469°N 122.70227°W.

Works

- McLoughlin and Old Oregon: A Chronicle (1900)

- The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark (1902)

- McDonald of Oregon: A Tale of Two Shores (1906)

- "Historical Sketch of Oregon City", chapter in Portland, Oregon: Its History and Builders by Joseph Gaston, 1911.

- The Soul of America: An Oregon Iliad (1934)

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-12-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Katrine Barber, Portland State University, writing in the Oregon Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 3 (Fall 2005).

- Eva Emery Dye, quoted in the Historical Marker Database

- Etulain, Richard (September 4, 2011). "A brief history of Oregon historians". The Oregonian.

- Oregon Encyclopedia Project

- Oregon History Project -- Oregon Biographies

- Quoted in Sacagawea of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Ella E. Clark and Margot Edmunds (University of California Press), page 92.

- Quoted in Sacagawea of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Ella E. Clark and Margot Edmunds (University of California Press), page 94.

- Quoted in Sacagawea of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Ella E. Clark and Margot Edmunds (University of California Press), page 95.

External links

- Works by Eva Emery Dye at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Eva Emery Dye at Internet Archive

- Works by Eva Emery Dye at Open Library

- "Eva Emery Dye". The Oregon Encyclopedia.

- Online Guide to the Eva Emery Dye Papers, Northwest Digital Archives

- Portrait from Oregon Historical Society digital collections