Chinookan peoples

Chinookan peoples include several groups of indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest in the United States who speak the Chinookan languages. Chinookan-speaking peoples reside along the Lower and Middle Columbia River (Wimahl) (″Big River″) from the river's gorge (near the present town of The Dalles, Oregon) downstream (west) to the river's mouth, and along adjacent portions of the coasts, from Tillamook Head of present-day Oregon in the south, north to Willapa Bay in southwest Washington. In 1805 the Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered the Chinook Tribe on the lower Columbia.[2] There are several theories about where the name ″Chinook″ came from. Some say it is a Chehalis word Tsinúk for the inhabitants of and a particular village site on Baker Bay, or "Fish Eaters". It may also be a word meaning "strong fighters".

Chinook people meet the Corps of Discovery on the Lower Columbia, October 1805 (by Charles M. Russell, 1905) | |

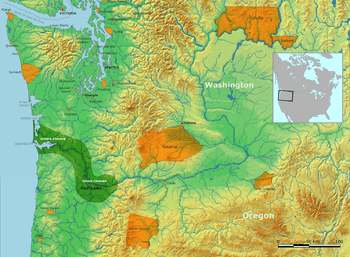

Location of Chinookan territory early in the 19th century | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2700[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Oregon – Washington) | |

| Languages | |

| Chinook Jargon, English, formerly Chinookan languages | |

| Religion | |

| traditional tribal religion |

Some Chinookan speaking people are part of several federally recognized Tribes: the Yakama Nation (primarily Wishram, upper Washington side Chinookans), the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation (primarily Wasco, Upper Oregon side Chinookans), Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde (Middle Chinookan people), Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians (Upper and Middle Chinookans).

The Chinook Indian Nation, consisting of the five western most Tribes of Chinookan peoples, Lower Chinook, Clatsop, Willapa, Wahkiakum and Kathlamet is currently (2019) working to obtain federal recognition. The Chinook Nation gained Federal Recognition in 2001 from the Department of Interior under President Bill Clinton.[3] After President George W. Bush was elected, his political appointees reviewed the case and, in a highly unusual action, revoked the recognition.[4]

The Chinook Nation sought Congressional support for recognition by the legislature in 2008 with a Bill Introduced by Brian Baird.[5] The Bill died in Congress.

The unrecognized Tchinouk Indians of Oregon trace their Chinook ancestry to two Chinook women who married French Canadians traders from the Hudson's Bay Company prior to 1830. The specific Chinook band these women were from or if they were Lower or Upper Chinook could not be determined. These individuals, settled in the French Prairie region of northwestern Oregon, becoming part of the community of French-Canadians and Métis (Mix-Bloods). There is no evidence that they are a distinct Indian community within French Prairie. The Chinook Indian Nation denied that the Tchinouk had any common history with them or any organizational affiliation. On January 16, 1986, the Bureau of Indian Affairs determined that the Tchinouk Indians of Oregon do not meet the requirements necessary to be a federally recognized tribe.

The unrecognized Clatsop-Nehalem Confederate Tribes was formed in 2000.[6] The Clatsop-Nehalem have approximately 130 members and claim to have Chinookan and Salish-speaking Tillamook (Nehalem) ancestry. This is contested by the Chinook Indian Nation. The Indian Claims Commission, Docket 234, found, in 1957, that the Clatsop Chinooks were part of the Chinook Indian Nation.[7] The Indian Claims Commission also found in Docket 240, 1962, that the Nehalem people were part of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians.[8]

Historic culture

The Chinookan peoples were relatively settled and occupied traditional tribal geographic areas, where they hunted and fished; salmon was a mainstay of their diet. The women also gathered and processed many nuts, seeds, roots and other foods. They had a society marked by social stratification, consisting of a number of distinct social castes of greater or lesser status.[9] Upper castes included shamans, warriors, and successful traders. They composed a minority of the community population compared to common members.[9] Members of the superior castes are said to have practiced social discrimination, limiting contact with commoners and forbidding play between the children of the different social groups.[10]

Some Chinookan peoples practiced slavery, a practice borrowed from the northernmost tribes of the Pacific Northwest.[11] They took slaves as captives in warfare, and used them to practice thievery on behalf of their masters. The latter refrained from such practices as unworthy of high status.[10]

The elite of some Chinookan tribes had the practice of head binding, flattening their children's forehead and top of the skull as a mark of social status. They bound the infant's head under pressure between boards when the infant was about 3 months old and continued until the child was about one year of age.[12] This custom was a means of marking social hierarchy; flat-headed community members had a rank above those with round heads. Those with flattened skulls refused to enslave other persons who were similarly marked, thereby reinforcing the association of a round head with servility.[12] The Chinook were known colloquially by early white explorers in the region as "Flathead Indians."

Living near the coast of the Pacific Ocean, the Chinook were skilled elk hunters and fishermen. The most popular fish was salmon. Owing partly to their settled living patterns, the Chinook and other coastal tribes had relatively little conflict over land, as they did not migrate through each other's territories and they had rich resources in the natural environment. In the manner of numerous settled tribes, the Chinook resided in longhouses. More than fifty people, related through extended kinship, often resided in one longhouse. Their longhouses were made of planks made from red cedar trees. The houses were about 20–60 feet wide and 50–150 feet long.

Today

The Chinook peoples have long had a community on the lower Columbia River. They re-organized in the 20th century, setting up an elected form of government and reviving tribal culture. They first sought recognition as a federally recognized sovereign tribe in the late 20th century, as this would provide certain benefits for education and welfare. The Department of Interior's Bureau of Indian Affairs rejected their application in 1997.[13] Since the late 20th century, the Chinook Indian Nation has engaged in a continuing effort to secure formal recognition, conducting research and developing documentation to demonstrate its history. They are referred to in government and historic accounts, but never made a treaty with the government to cede land and establish a reservation, which would have meant automatic recognition.[14]

In 2001, the U.S. Department of Interior recognized the Chinook Indian Nation, a confederation of the Cathlamet, Clatsop, Lower Chinook, Wahkiakum and Willapa Indians, as a tribe, according to its rules established in consultation with other recognized tribes. The tribe had documented continuity of their community over time on the lower Columbia. This recognition was announced during the last months of the administration of President Bill Clinton.[15] have Allotments on the timber-rich Quinault Reservation in Grays Harbor County, Washington. The Quinault appealed recognition of the Chinook in August 2001, and the matter was taken up by the new administration.[13]

After President George W. Bush was elected, his new political appointees reviewed the Chinook materials. In 2002, in a highly unusual action, they revoked the recognition of the Chinook and of two other tribes also approved by the previous administration.[16] Efforts by Brian Baird, D-Wash. from Washington's 3rd congressional district, to gain passage of legislation in 2011 to achieve recognition of the tribe were not successful.[1] In his decision on a lawsuit filed in late 2017, U.S. District Court Judge Ronald B. Leighton ruled recognition could only be granted from Congress and other branches of government, but largely sided with the tribe; Leighton denied seven of eight claims by the Interior Department to dismiss the case, including a challenge to a 2015 rule that bars tribes from seeking recognition again.[17]

The Chinook Indian Nation's offices are in Bay Center, Washington. The tribe holds an Annual Winter Gathering at the plankhouse in Ridgefield, Washington. It also holds an Annual First Salmon Ceremony at Chinook Point (Fort Columbia) on the North Shore of the Columbia River.[18]

List of Chinookan peoples

Chinookan-speaking groups include:

- Lower Chinook or Chinook proper (today enrolled in the Quinault Indian Nation, and part of the unrecognized Chinook Indian Nation)

- Kathlamet or Cathlamet (Cathlahmah) (at the mouth of the Columbia River in modern Oregon and Washington, part of the unrecognized Chinook Indian Nation)

- Clackamas or Cathlascans (″Those along the Clackamas River″, inhabited the Willamette Valley on the eastbank of the Willamette River as far as the Willamette Falls, above and below the Falls themselves on either bank, and along the Clackamas River and Sandy Rivers. Lewis and Clark estimated their population at 1800 persons in 1806. At the time the tribe lived in 11 villages and subsisted on fish and roots. By 1855, the 88 surviving members of the tribe were relocated to the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon)

- Clatsop (around the mouth of the Columbia River and the Clatsop Plains in northwestern Oregon, Chief Coboway welcomed Lewis and Clark; by 1840, the number of Clatsop Indians was 200, in 1850 the number was down by half; today part of Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, and the unrecognized Chinook Indian Nation and Clatsop Nehalem Confederated Tribes)

- Clowwewalla, also (Willamette) Falls Indians or Tumwater Falls Indians (controlled the Willamette Valley, Oregon, perhaps a subgroup of the Clackamas, may have included the Cushook, Chahcowah, and Nemalquinner of Lewis and Clark, who estimated that they numbered 650 in 1805-6. On this basis Mooney (1928) estimated there might have been 900 in 1780. They were greatly reduced by the epidemic of 1829 and in 1851 numbered 13 and are now apparently extinct. Maybe some survive as Clackamas as part of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon)[19]

- Wasco-Wishram

- Wasco (known also by their Sahaptin name as Wascopam, lived traditionally on the south bank of the Columbia River, Oregon, they were divided into three subtribes: the Dalles Wasco or Wasco proper (near The Dalles in Wasco County), the Hood River Wasco (along the Hood River to its mouth into the Columbia River, sometimes divided into two bands: the Hood River Band in Oregon, and the White Salmon River Band in Washington). In 1822 their population was estimated to be 900, today 200 tribal members out of 4,000 of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs are estimated to be Wasco)

- Wishram (a Yakama-Sahaptin term), their autonym as Ita'xluit was the source of transliteration as Tlakluit or Echelut (Echeloot) (lived traditionally on the north bank of the Columbia River, Washington, Wishram village or Nixlúidix ("trading place") near Five Mile Rapids, was the center of the regional trade system for Pacific Coast, Plateau, Great Basin and Plains tribes, in the 1700s, the estimated Wishram population was 1,500. In 1962 only 10 Wishrams were counted on the Washington census, today they are predominantly enrolled in the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation)

- Chilluckittequaw or Chiluktkwa (living on the north side of Columbia River in Klickitat and Skamania counties, Washington, from about 10 miles below the Dalles to the neighborhood of the Cascades. In 1806 Lewis and Clark estimated their number at 2,400. According to Mooney a remnant of the tribe lived near the mouth of White Salmon River until 1880, when they removed to the Cascades, where a few still resided in 1895, today sometimes considered as White Salmon River Band of Washington of the Hood River Wasco subtribe)

- Watlata or Cascades Indians (lived downstream from the other Wasco groups and were divided in two groups, one on each side of the Columbia River and at the Cascades of the Columbia River and the Willamette River in Oregon; the Oregon group were called Gahlawaihih [Curtis]). The Watlala, whose dialect is the most divergent dialect of the Wasco, may have been a separate tribe though identified as Wasco since 1830, and enrolled as "Ki-gal-twal-la band of the Wasco" and the "Dog River band of the Wasco″ in Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs)

- Kilooklaniuck[20] (extinct as a tribe)

- Multnomah or Cathlascans (living in approximately 15 villages on Sauvie Island (Wappatoo / Wapato Island) (hosting a total of 2,000 people who built and resided in cedar log houses 30 yards long by 12 yards wide), other villages were located along Multnomah Channel and in the Wapato Valley near the mouth of the Willamette (Multnomah) River into the Columbia River and generally along the western Willamette riverbank, also known as Wappato / Wapato people after Wappato/Wapato (Indian potato), an marsh-grown plant like a potato or onion and important staple food for Native peoples, today part of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, a minority are enrolled in the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon)

- Skillot (occupied both sides of the Columbia River, between the Washougal River (from the Cascades Chinook placename: [wasiixwal] or [wasuxal], meaning "rushing water") and Cowlitz River; Clark mentioned one village of 25 houses, made of wooden planks with straw roofs. Altogether, the Corps estimated the Skilloot population in 1806 to be about 2,500. An 1850 population estimate put the tribe at about 200 surviving members. The Skilloot no longer exist as an independent band.)

- Wahkiakum, Wackiakum, Wac-ki-cum or Wahkiaku ("tall timber [in reverence to the plank houses", another source gives ″region downriver″,[21] lived in two villages along the Elochoman River on the north bank of the Columbia River, Washington, opposite of the Kathlamet in Oregon; sometimes considered a Kathlamet village group under the leadership of Chief Wahkiakum, part of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, and of the unrecognized Chinook Indian Nation)

- Willapa Chinook (along the north bank of the Columbia River in southwestern Washington around southern Willapa Bay, from Cape Disappointment to Grays Harbor, today enrolled in the federally recognized Shoalwater Bay Tribe and the unrecognized Chinook Indian Nation)

In the 21st century, most Chinook live in the towns of Bay Center, Chinook, and Ilwaco in southwest Washington and in Astoria, Oregon.

Books written about the Chinook include the novel Boston Jane: An Adventure by Jennifer L. Holm

Notable Chinook

- Comcomly, chief in the early to mid-19th century

- Charles Cultee, the principal informant to early 20th-century anthropologist Franz Boas on his language and tribal studies, especially for Chinook Texts.

- Ranald MacDonald, mixed-race son of Archibald McDonald, a Scottish Hudson's Bay Company fur trader, and Raven, Chief Concomly's daughter, in Astoria, Oregon, was the first Westerner to teach English in Japan, in 1847–1848. He taught Einosuke Moriyama, who served as one of the chief interpreters during negotiations between Commodore Perry and the Tokugawa Shogunate

- J. Christopher Stevens, American diplomat and lawyer who served as the U.S. Ambassador to Libya from June 2012 to September 2012. He was killed when the U.S. consulate was attacked in Benghazi, Libya, on September 11, 2012[22]

- Catherine Troeh, historian, artist, activist and advocate for Native American rights and culture. An elder of the Chinook tribe, she was a direct descendant of Chief Comcomly.

- Chief Tumulth, signed the 1855 treaty that created the Grand Ronde Reservation; he was later killed by Gen. Philip Sheridan's forces[23]

- Tsin-is-tum, "Princess Jennie Michel", a Native American folklorist. Called "Last of the Clatsops."

See also

- Chinook salmon

- Chinook (wind)

- Boeing CH-47 Chinook

References

- Wilson, Katie (7 October 2014). "Recognition move by Oregon tribe stirs Chinook concerns". Chinook Observer. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- The term "Chinook" also has a wider meaning in reference to the Chinook Jargon, which is based on Chinookan languages, in part, and so the term "Chinookan" was coined by linguists to distinguish the older language from its offspring, Chinuk Wawa.

- https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2001/01/09/01-609/final-determination-to-acknowledge-the-chinook-indian-tribechinook-nation-formerly-chinook-indian

- https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2002/07/12/02-17551/reconsidered-final-determination-to-decline-to-acknowledge-the-chinook-indian-tribechinook-nation

- https://www.chinookobserver.com/news/congressman-tries-a-different-approach-to-secure-recognition-for-chinook/article_3a98557a-c4c4-56fd-8ba4-74d460965609.html

- http://egov.sos.state.or.us/br/pkg_web_name_srch_inq.show_detl?p_be_rsn=233779&p_srce=BR_INQ&p_print=FALSE

- https://cdm17279.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p17279coll10/id/398/rec/1

- https://cdm17279.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p17279coll10/id/809/rec/3

- Robert H. Ruby and John A. Brown, Indian Slavery in the Pacific Northwest. Spokane, WA: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1993; pg. 42.

- Ruby and Brown, Indian Slavery in the Pacific Northwest, p. 43.

- Ruby and Brown, Indian Slavery in the Pacific Northwest, p. 39.

- Ruby and Brown, Indian Slavery in the Pacific Northwest, pg. 47.

- Amy McFall Prince, "Feds revoke tribe's status", The Daily News (TDN), 6 July 2002; accessed 25 November 2016

- "Chinook tribe pushes for recognition, again". The Oregonian, p A1+. The Oregonian. November 30, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- Federal Register, Volume 66, Number 6 (Tuesday, January 9, 2001)

- For the 2001 recognition, see 66 Federal Register 1690 (2001) at indianz.com Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine; for the subsequent reversal, see 67 Federal Register 46204 (2002) at frwebgate5.access.gpo.gov

- Solomon, Molly. "Chinook Tribe A Step Closer To Recognition As Federal Judge Advances Claims". www.opb.org. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-06-22. Retrieved 2005-06-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Clackamas Chinook people

- Chinook Indian Nation - Our Coast

- the ″Wahkiakum″ are often mistaken for the Lower Snake River Sahaptin-speaking local group or band of ″Wauyukma″

- "President Obama, Hillary Clinton pay tribute to slain Chinook member Stevens", Chinook Observer Newspaper, September 14, 2012 Archived January 19, 2013, at Archive.today

- Chuck Williams. "Kalliah Tumulth (Indian Mary) (1854-1906)". The Oregon Encyclopedia.

Further reading

- Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia Published by University of Washington Press, 2013 - ISBN 978-0-295-99279-2

- Judson, Katharine Berry (1912). Myths and legends of the Pacific Northwest, especially of Washington and Oregon (DJVU). Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection (2nd ed.). McClurg. OCLC 10363767. Oral traditions from the Chinook, Nez Perce, Klickitat and other tribes of the Pacific Northwest.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinookan. |