Ouroboros

The ouroboros or uroboros (/ˌ(j)ʊərəˈbɒrəs/, also UK: /uːˈrɒbərɒs/,[2][3] US: /-oʊs/) is an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon[4] eating its own tail. Originating in ancient Egyptian iconography, the ouroboros entered western tradition via Greek magical tradition and was adopted as a symbol in Gnosticism and Hermeticism and most notably in alchemy. The term derives from Ancient Greek: οὐροβόρος,[5] from οὐρά (oura), "tail"[6] + βορά (bora), "food",[7] from βιβρώσκω (bibrōskō), "I eat".[8] The ouroboros is often interpreted as a symbol for eternal cyclic renewal or a cycle of life, death, and rebirth. The skin-sloughing process of snakes symbolizes the transmigration of souls, the snake biting its own tail is a fertility symbol. The tail of the snake is a phallic symbol, the mouth is a yonic or womb-like symbol.[9]

Historical representations

Ancient Egypt

The first known appearance of the ouroboros motif is in the Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, an ancient Egyptian funerary text in KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun, in the 14th century BC. The text concerns the actions of the god Ra and his union with Osiris in the underworld. The ouroboros is depicted twice on the figure: holding their tails in their mouths, one encircling the head and upper chest, the other surrounding the feet of a large figure, which may represent the unified Ra-Osiris (Osiris born again as Ra). Both serpents are manifestations of the deity Mehen, who in other funerary texts protects Ra in his underworld journey. The whole divine figure represents the beginning and the end of time.[10]

The ouroboros appears elsewhere in Egyptian sources, where, like many Egyptian serpent deities, it represents the formless disorder that surrounds the orderly world and is involved in that world's periodic renewal.[11] The symbol persisted in Egypt into Roman times, when it frequently appeared on magical talismans, sometimes in combination with other magical emblems.[12] The 4th-century AD Latin commentator Servius was aware of the Egyptian use of the symbol, noting that the image of a snake biting its tail represents the cyclical nature of the year.[13]

Alchemy and Gnosticism

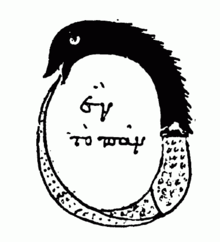

The famous ouroboros drawing from the early alchemical text, The Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra (Κλεοπάτρης χρυσοποιία), probably originally dating to third century Alexandria but first known in a tenth century copy, encloses the words hen to pan (ἓν τὸ πᾶν), "the all is one". Its black and white halves may perhaps represent a Gnostic duality of existence, analogous to the Taoist yin and yang symbol.[14] The chrysopoeia ouroboros of Cleopatra the Alchemist is one of the oldest images of the ouroboros to be linked with the legendary opus of the alchemists, the philosopher's stone.

An aim of alchemists and adepts, described as "individual self-perfection through physical transmutation and spiritual transcendence",[15] was familiar to the alchemist and physician Sir Thomas Browne. It focused on the eternal unity of all things as well as the cycle of birth and death (from which the alchemist sought release and liberation).[16] In his A Letter to a Friend, a medical treatise full of case-histories and witty speculations upon the human condition, he wrote:

... that the first day should make the last, that the Tail of the Snake should return into its Mouth precisely at that time, and they should wind up upon the day of their Nativity, is indeed a remarkable Coincidence ...

In Gnosticism, a serpent biting its tail symbolized eternity and the soul of the world.[17] The Gnostic Pistis Sophia (c. 400 AD) describes the ouroboros as a twelve-part dragon surrounding the world with its tail in its mouth.[18]

A 15th-century alchemical manuscript, The Aurora Consurgens, features the ouroboros, where it is used amongst symbols of the sun, moon, and mercury.[19]

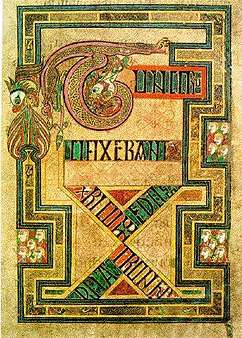

A highly stylized ouroboros from The Book of Kells, an illuminated Gospel Book (c. 800 AD)

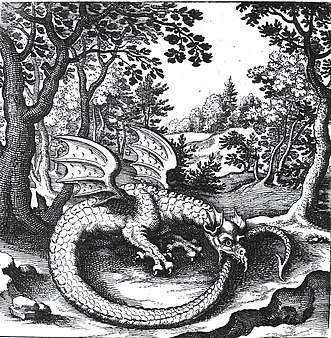

A highly stylized ouroboros from The Book of Kells, an illuminated Gospel Book (c. 800 AD) Engraving of an wyvern-type ouroboros by Lucas Jennis, in the 1625 alchemical tract De Lapide Philosophico. The figure serves as a symbol for mercury.[20]

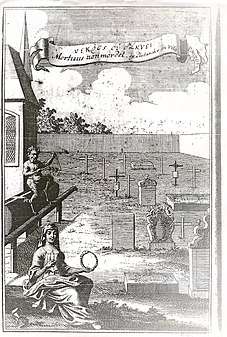

Engraving of an wyvern-type ouroboros by Lucas Jennis, in the 1625 alchemical tract De Lapide Philosophico. The figure serves as a symbol for mercury.[20] An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft's 1734 treatise on vampires.

An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft's 1734 treatise on vampires. Seal of the Theosophical Society, founded 1875

Seal of the Theosophical Society, founded 1875- In John William Waterhouse's The Magic Circle (1886), the depicted witch wears a live snake as an Ouroboros

The "world serpent" in mythology

In Norse mythology, the ouroboros appears as the serpent Jörmungandr, one of the three children of Loki and Angrboda, which grew so large that it could encircle the world and grasp its tail in its teeth. In the legends of Ragnar Lodbrok, such as Ragnarssona þáttr, the Geatish king Herraud gives a small lindworm as a gift to his daughter Þóra Town-Hart after which it grows into a large serpent which encircles the girl's bower and bites itself in the tail. The serpent is slain by Ragnar Lodbrok who marries Þóra. Ragnar later has a son with another woman named Kráka and this son is born with the image of a white snake in one eye. This snake encircled the iris and bit itself in the tail, and the son was named Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye.[21]

It is a common belief among indigenous people of the tropical lowlands of South America that waters at the edge of the world-disc are encircled by a snake, often an anaconda, biting its own tail.[22]

Symbol of Birth, death and rebirth

The Ouroboros symbol is a common sight on 17th and 18th century gravestones. Varying from region to region some have legs and even torso like bodies while others are carved in a bracelet like circle. They appear alongside the hourglass, skulls, bible, and cherubs that are so common in depictions of mortality of this era. And like those other symbols, they disappeared from gravestones in the 19th century Gothic revival.

Connection to Indian thought

In the Aitareya Brahmana, a Vedic text of the early 1st millennium BCE, the nature of the Vedic rituals is compared to "a snake biting its own tail."[23]

Ouroboros symbolism has been used to describe the Kundalini. According to the medieval Yoga-kundalini Upanishad, "The divine power, Kundalini, shines like the stem of a young lotus; like a snake, coiled round upon herself she holds her tail in her mouth and lies resting half asleep as the base of the body" (1.82).

Storl (2004) also refers to the ouroboros image in reference to the "cycle of samsara".[24]

Modern references

Jungian psychology

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung saw the ouroboros as an archetype and the basic mandala of alchemy. Jung also defined the relationship of the ouroboros to alchemy:[25][26]

The alchemists, who in their own way knew more about the nature of the individuation process than we moderns do, expressed this paradox through the symbol of the Ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail. The Ouroboros has been said to have a meaning of infinity or wholeness. In the age-old image of the Ouroboros lies the thought of devouring oneself and turning oneself into a circulatory process, for it was clear to the more astute alchemists that the prima materia of the art was man himself. The Ouroboros is a dramatic symbol for the integration and assimilation of the opposite, i.e. of the shadow. This 'feed-back' process is at the same time a symbol of immortality, since it is said of the Ouroboros that he slays himself and brings himself to life, fertilizes himself and gives birth to himself. He symbolizes the One, who proceeds from the clash of opposites, and he therefore constitutes the secret of the prima materia which ... unquestionably stems from man's unconscious.

The Jungian psychologist Erich Neumann writes of it as a representation of the pre-ego "dawn state", depicting the undifferentiated infancy experience of both mankind and the individual child.[27]

Kekulé's dream

.png)

The German organic chemist August Kekulé described the eureka moment when he realized the structure of benzene, after he saw a vision of Ouroboros:[28]

I was sitting, writing at my text-book; but the work did not progress; my thoughts were elsewhere. I turned my chair to the fire and dozed. Again the atoms were gamboling before my eyes. This time the smaller groups kept modestly in the background. My mental eye, rendered more acute by the repeated visions of the kind, could now distinguish larger structures of manifold conformation: long rows, sometimes more closely fitted together; all twining and twisting in snake-like motion. But look! What was that? One of the snakes had seized hold of its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. As if by a flash of lightning I awoke; and this time also I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis.

Cosmos

Martin Rees used the ouroboros to illustrate the various scales of the universe, ranging from 10−20 cm (subatomic) at the tail, up to 1025 cm (supragalactic) at the head.[29] Rees stressed "the intimate links between the microworld and the cosmos, symbolised by the ouraborus",[30] as tail and head meet to complete the circle.

Armadillo girdled lizard

The genus of the armadillo girdled lizard, Ouroborus cataphractus, takes its name from the animal's defensive posture: curling into a ball and holding its own tail in its mouth.[31]

Mathematics and Computer Science

The paradoxical self-referential behavior of algorithms involving recursive or metaprogramming constructs, such as The Meta-circular evaluator, are often explained using the ouroboros as a metaphor.

Consider the Fixed-point combinator, expressed through a Symbolic Expression:

[ dfn ( fix M ) ( M ( fix M ) ) ]

See also

- Autopoiesis

- Biscione

- Causality

- Crosier

- Cyclic model

- Cyclical pattern

- Dragon (M. C. Escher)

- Endless knot

- Ensō

- Eternal return (Eliade)

- Eternalism (philosophy of time)

- Feedback

- Jishin-no-ben

- Historic recurrence

- Hoop snake

- Infinite loop

- Jörmungandr

- Moebius Strip

- Recursion

- Strange loop

- Three hares

- Tsuchinoko

- AURYN

- Wyvern

- Valknut

- The Worm Ouroboros – notable fictional appearance

References

Notes

- The Codex Parisinus graecus 2327 in the Bibliothèque Nationale, France, referred to in "alchemy", The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0199545561

- "uroboros". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "Definition of 'ouroboros'". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "Salvador Dalí: Alchimie des Philosophes | The Ouroboros". Academic Commons. Willamette University.

- Liddell & Scott (1940), οὐροβόρος

- Liddell & Scott (1940), οὐρά

- Liddell & Scott (1940), βορά

- Liddell & Scott (1940), βιβρώσκω

- Arien Mack: Humans and Other Animals, Ohio State University Press, 1999, p.359

- Hornung, Erik. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Cornell University Press, 1999. pp. 38, 77–78

- Hornung, Erik. Conceptions of God in Egypt: The One and the Many. Cornell University Press, 1982. pp. 163–64.

- Hornung 2002, p. 58.

- Servius, note to Aeneid 5.85: "according to the Egyptians, before the invention of the alphabet the year was symbolized by a picture, a serpent biting its own tail, because it recurs on itself" (annus secundum Aegyptios indicabatur ante inventas litteras picto dracone caudam suam mordente, quia in se recurrit), as cited by Danuta Shanzer, A Philosophical and Literary Commentary on Martianus Capella's De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii Book 1 (University of California Press, 1986), p. 159.

- Eliade, Mircea. Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashions. Chicago and London: U of Chicago Press, 1976. p.55; Ch.6, p. 93–113

- http://alchemylife.org/Better_Living_Through_Alchemy_Vol_I.pdf BETTER LIVING THROUGH ALCHEMY VOLUME I: ORIGINS OF ALCHEMY By Lynn Osburn© 1994-2008

- For illustrative specificity on how the Ourobouros sexually symbolized this unity in alchemy and in Phibionite Gnosticism, consult: Eliade, Mircea. Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashions. Chicago and London: U of Chicago Press, 1976. pp. 55; 109–119. ISBN 0-226-20391-3.

- Origen, Contra Celsum 6.25.

- Hornung 2002, p. 76.

- http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20171204-the-ancient-symbol-that-spanned-millennia

- Lambsprinck: De Lapide Philosophico. E Germanico versu Latine redditus, per Nicolaum Barnaudum Delphinatem .... Sumptibus LUCAE JENNISSI, Frankfurt 1625, p. 17.

- Jurich, Marilyn (1998). Scheherazade's Sisters: Trickster Heroines and Their Stories in World Literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313297243.

- Roe, Peter (1986), The Cosmic Zygote, Rutgers University Press

- Witzel, M., "The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools : The Social and Political Milieu" in Witzel, Michael (ed.) (1997), Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts. New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas, Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora vol. 2, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 325 footnote 346

- "When Shakti is united with Shiva, she is a radiant, gentle goddess; but when she is separated from him, she turns into a terrible, destructive fury. She is the endless Ouroboros, the dragon biting its own tail, symbolizing the cycle of samsara." Storl, Wolf-Dieter (2004). Shiva: The Wild God of Power and Ecstasy. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-59477-780-6.

- Carl Jung, Collected Works, Vol. 14 para. 513

- "Jung defines ouroboros to alchemy". Snakes in Dreams. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- Neumann, Erich. (1995). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Bollington series XLII: Princeton University Press. Originally published in German in 1949.

- Read, John (1957). From Alchemy to Chemistry. pp. 179–180. ISBN 9780486286907.

- M Rees Just Six Numbers (London 1999) p. 7-8

- M Rees Just Six Numbers (London 1999) p. 161

- Stanley, Edward L.; Bauer, Aaron M.; Jackman, Todd R.; Branch, William R.; Mouton, P. Le Fras N. (2011). "Between a rock and a hard polytomy: Rapid radiation in the rupicolous girdled lizards (Squamata: Cordylidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 58 (1): 53–70. (Ouroborus cataphractus, new combination).

Bibliography

- Bayley, Harold S (1909). New Light on the Renaissance. Kessinger. Reference pages hosted by the University of Pennsylvania

- Hornung, Erik (2002). The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. Cornell University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press – via perseus.tufts.edu.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ouroboros. |