Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyyā al-Rāzī (Persian: ابوبكر محمّد زکرياى رازى Abūbakr Mohammad-e Zakariyā-ye Rāzī, also known by his Latinized name Rhazes (/ˈrɑːziːz/)[3] or Rasis; 854–925 CE), was a Persian[4][5][6] polymath, physician, alchemist, philosopher, and important figure in the history of medicine. He also wrote on logic, astronomy and grammar.[7]

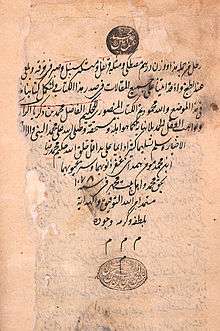

Al-Razi Abūbakr Mohammad-e Zakariyyā-ye Rāzī ابوبكر محمّد زکرياى رازى | |

|---|---|

_(AD_865_-_925)_Wellcome_L0005053_(cropped).jpg) | |

| Born | 854 CE[1] Ray, Abbasid Caliphate (Iran)[2] |

| Died | 932 (aged 77–78) or 925 (aged 70–71)[2] Ray, Samanid Empire (Iran) |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Region | Islamic philosophy |

Main interests | Medicine, philosophy, alchemy, |

Notable ideas | The first to produce acids such as sulfuric acid, writing up limited or extensive notes on diseases such as smallpox and chickenpox, a pioneer in ophthalmology, author of the first book on pediatrics, making leading contributions in inorganic and organic chemistry, also the author of several philosophical works. |

A comprehensive thinker, Razi made fundamental and enduring contributions to various fields, which he recorded in over 200 manuscripts, and is particularly remembered for numerous advances in medicine through his observations and discoveries.[8] An early proponent of experimental medicine, he became a successful doctor, and served as chief physician of Baghdad and Ray hospitals.[9][10] As a teacher of medicine, he attracted students of all backgrounds and interests and was said to be compassionate and devoted to the service of his patients, whether rich or poor.[11]

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), he was among the first to use humoral theory to distinguish one contagious disease from another, and wrote a pioneering book about smallpox and measles providing clinical characterization of the diseases.[12] He also discovered numerous compounds and chemicals including alcohol and sulfuric acid.[13][14]

Through translation, his medical works and ideas became known among medieval European practitioners and profoundly influenced medical education in the Latin West.[9] Some volumes of his work Al-Mansuri, namely "On Surgery" and "A General Book on Therapy", became part of the medical curriculum in Western universities.[9] Edward Granville Browne considers him as "probably the greatest and most original of all the Muslim physicians, and one of the most prolific as an author".[15] Additionally, he has been described as the father of pediatrics,[16][17] and a pioneer of obstetrics and ophthalmology.[18] For example, he was the first to recognize the reaction of the eye's pupil to light.[17]

Biography

Razi was born in the city of Ray (modern Rey) situated on the Great Silk Road that for centuries facilitated trade and cultural exchanges between East and West.[19] His nisba, Râzī (رازی), means "from the city of Ray" in Persian.[20] It is located on the southern slopes of the Alborz mountain range situated near Tehran, Iran.

In his youth, Razi moved to Baghdad where he studied and practiced at the local bimaristan (hospital). Later, he was invited back to Rey by Mansur ibn Ishaq, then the governor of Rey, and became a bimaristan's head.[2] He dedicated two books on medicine to Mansur ibn Ishaq, The Spiritual Physic and Al-Mansūrī on Medicine.[2][21][22][23] Because of his newly acquired popularity as physician, Razi was invited to Baghdad where he assumed the responsibilities of a director in a new hospital named after its founder al-Muʿtaḍid (d. 902 CE).[2] Under the reign of Al-Mutadid's son, Al-Muktafi (r. 902-908) Razi was commissioned to build a new hospital, which should be the largest of the Abbasid Caliphate. To pick the future hospital's location, Razi adopted what is nowadays known as an evidence-based approach suggesting having fresh meat hung in various places throughout the city and to build the hospital where meat took longest to rot.[24]

He spent the last years of his life in his native Rey suffering from glaucoma. His eye affliction started with cataracts and ended in total blindness.[25] The cause of his blindness is uncertain. One account mentioned by Ibn Juljul attributed the cause to a blow to his head by his patron, Mansur ibn Ishaq, for failing to provide proof for his alchemy theories;[26] while Abulfaraj and Casiri claimed that the cause was a diet of beans only.[27][28] Allegedly, he was approached by a physician offering an ointment to cure his blindness. Al-Razi then asked him how many layers does the eye contain and when he was unable to receive an answer, he declined the treatment stating "my eyes will not be treated by one who does not know the basics of its anatomy".[29]

The lectures of Razi attracted many students. As Ibn al-Nadim relates in Fihrist, Razi was considered a shaikh, an honorary title given to one entitled to teach and surrounded by several circles of students. When someone raised a question, it was passed on to students of the 'first circle'; if they did not know the answer, it was passed on to those of the 'second circle', and so on. When all students would fail to answer, Razi himself would consider the query. Razi was a generous person by nature, with a considerate attitude towards his patients. He was charitable to the poor, treated them without payment in any form, and wrote for them a treatise Man La Yaḥḍuruhu al-Ṭabīb, or Who Has No Physician to Attend Him, with medical advice.[30] One former pupil from Tabaristan came to look after him, but as al-Biruni wrote, Razi rewarded him for his intentions and sent him back home, proclaiming that his final days were approaching.[31] According to Biruni, Razi died in Rey in 925 sixty years of age.[32] Biruni, who considered Razi as his mentor, among the first penned a short biography of Razi including a bibliography of his numerous works.[32]

Ibn al-Nadim recorded an account by Razi of a Chinese student who copied down all of Galen's works in Chinese as Razi read them to him out loud after the student learned fluent Arabic in 5 months and attended Razi's lectures.[33][34][35][36]

After his death, his fame spread beyond the Middle East to Medieval Europe, and lived on. In an undated catalog of the library at Peterborough Abbey, most likely from the 14th century, Razi is listed as a part author of ten books on medicine.[37]

Contributions to medicine

Psychology and psychotherapy

Al-Razi was one of the world's first great medical experts. He is considered the father of psychology and psychotherapy.[38]

Smallpox vs. measles

Razi wrote:

Smallpox appears when blood "boils" and is infected, resulting in vapours being expelled. Thus juvenile blood (which looks like wet extracts appearing on the skin) is being transformed into richer blood, having the color of mature wine. At this stage, smallpox shows up essentially as "bubbles found in wine" (as blisters)... this disease can also occur at other times (meaning: not only during childhood). The best thing to do during this first stage is to keep away from it, otherwise this disease might turn into an epidemic.

This diagnosis is acknowledged by the Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), which states: "The most trustworthy statements as to the early existence of the disease are found in an account by the 9th-century Persian physician Rhazes, by whom its symptoms were clearly described, its pathology explained by a humoral or fermentation theory, and directions given for its treatment."[39]

Razi's book al-Judari wa al-Hasbah (On Smallpox and Measles) was the first book describing smallpox and measles as distinct diseases.[40] It was translated more than a dozen times into Latin and other European languages. Its lack of dogmatism and its Hippocratic reliance on clinical observation show Razi's medical methods. For example, he wrote:

The eruption of smallpox is preceded by a continued fever, pain in the back, itching in the nose and nightmares during sleep. These are the more acute symptoms of its approach together with a noticeable pain in the back accompanied by fever and an itching felt by the patient all over his body. A swelling of the face appears, which comes and goes, and one notices an overall inflammatory color noticeable as a strong redness on both cheeks and around both eyes. One experiences a heaviness of the whole body and great restlessness, which expresses itself as a lot of stretching and yawning. There is a pain in the throat and chest and one finds it difficult to breathe and cough. Additional symptoms are: dryness of breath, thick spittle, hoarseness of the voice, pain and heaviness of the head, restlessness, nausea and anxiety. (Note the difference: restlessness, nausea and anxiety occur more frequently with "measles" than with smallpox. At the other hand, pain in the back is more apparent with smallpox than with measles). Altogether one experiences heat over the whole body, one has an inflamed colon and one shows an overall shining redness, with a very pronounced redness of the gums. (Rhazes, Encyclopaedia of Medicine)

Meningitis

Razi compared the outcome of patients with meningitis treated with blood-letting with the outcome of those treated without it to see if blood-letting could help.[41]

Pharmacy

Razi contributed in many ways to the early practice of pharmacy[42] by compiling texts, in which he introduces the use of "mercurial ointments" and his development of apparatus such as mortars, flasks, spatulas and phials, which were used in pharmacies until the early twentieth century.

Ethics of medicine

On a professional level, Razi introduced many practical, progressive, medical and psychological ideas. He attacked charlatans and fake doctors who roamed the cities and countryside selling their nostrums and "cures". At the same time, he warned that even highly educated doctors did not have the answers to all medical problems and could not cure all sicknesses or heal every disease, which was humanly speaking impossible. To become more useful in their services and truer to their calling, Razi advised practitioners to keep up with advanced knowledge by continually studying medical books and exposing themselves to new information. He made a distinction between curable and incurable diseases. Pertaining to the latter, he commented that in the case of advanced cases of cancer and leprosy the physician should not be blamed when he could not cure them. To add a humorous note, Razi felt great pity for physicians who took care for the well being of princes, nobility, and women, because they did not obey the doctor's orders to restrict their diet or get medical treatment, thus making it most difficult being their physician.

He also wrote the following on medical ethics:

The doctor's aim is to do good, even to our enemies, so much more to our friends, and my profession forbids us to do harm to our kindred, as it is instituted for the benefit and welfare of the human race, and God imposed on physicians the oath not to compose mortiferous remedies.[43]

Books and articles on medicine

This 23-volume set medical textbooks contains the foundation of gynecology, obstetrics and ophthalmic surgery[38]

- The Virtuous Life (al-Hawi الحاوي).

This monumental medical encyclopedia in nine volumes—known in Europe also as The Large Comprehensive or Continens Liber (جامع الكبير) ——contains considerations and criticism on the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plato, and expresses innovative views on many subjects.[44][45][46] Because of this book alone, many scholars consider Razi the greatest medical doctor of the Middle Ages.

The al-Hawi is not a formal medical encyclopedia, but a posthumous compilation of Razi's working notebooks, which included knowledge gathered from other books as well as original observations on diseases and therapies, based on his own clinical experience. It is significant since it contains a celebrated monograph on smallpox, the earliest one known. It was translated into Latin in 1279 by Faraj ben Salim, a physician of Sicilian-Jewish origin employed by Charles of Anjou, and after which it had a considerable influence in Europe.

The al-Hawi also criticized the views of Galen, after Razi had observed many clinical cases which did not follow Galen's descriptions of fevers. For example, he stated that Galen's descriptions of urinary ailments were inaccurate as he had only seen three cases, while Razi had studied hundreds of such cases in hospitals of Baghdad and Rey.[47]

- For One Who Has No Physician to Attend Him (Man la Yahduruhu Al-Tabib) (من لا يحضره الطبيب)—A medical adviser for the general public

Razi was possibly the first Persian doctor to deliberately write a home medical manual (remedial) directed at the general public. He dedicated it to the poor, the traveler, and the ordinary citizen who could consult it for treatment of common ailments when a doctor was not available. This book is of special interest to the history of pharmacy since similar books were very popular until the 20th century. Razi described in its 36 chapters, diets and drug components that can be found in either an apothecary, a market place, in well-equipped kitchens, or and in military camps. Thus, every intelligent person could follow its instructions and prepare the proper recipes with good results.

Some of the illnesses treated were headaches, colds, coughing, melancholy and diseases of the eye, ear, and stomach. For example, he prescribed for a feverish headache: " 2 parts of duhn (oily extract) of rose, to be mixed with 1 part of vinegar, in which a piece of linen cloth is dipped and compressed on the forehead". He recommended as a laxative, " 7 drams of dried violet flowers with 20 pears, macerated and well mixed, then strained. Add to this filtrate, 20 drams of sugar for a drink. In cases of melancholy, he invariably recommended prescriptions, which included either poppies or its juice (opium), Cuscuta epithymum (clover dodder) or both. For an eye-remedy, he advised myrrh, saffron, and frankincense, 2 drams each, to be mixed with 1 dram of yellow arsenic formed into tablets. Each tablet was to be dissolved in a sufficient quantity of coriander water and used as eye drops.

- Doubts About Galen (Shukuk 'ala alinusor)

In his book Doubts about Galen, Razi rejects several claims made by the Greek physician, as far as the alleged superiority of the Greek language and many of his cosmological and medical views. He links medicine with philosophy, and states that sound practice demands independent thinking. He reports that Galen's descriptions do not agree with his own clinical observations regarding the run of a fever. And in some cases he finds that his clinical experience exceeds Galen's.

He criticized Galen's theory that the body possessed four separate "humors" (liquid substances), whose balance are the key to health and a natural body-temperature. A sure way to upset such a system was to insert a liquid with a different temperature into the body resulting in an increase or decrease of bodily heat, which resembled the temperature of that particular fluid. Razi noted that a warm drink would heat up the body to a degree much higher than its own natural temperature. Thus the drink would trigger a response from the body, rather than transferring only its own warmth or coldness to it. (Cf. I. E. Goodman)

This line of criticism essentially had the potential to completely refute Galen's theory of humors, as well as Aristotle's theory of the four elements, on which it was grounded. Razi's own alchemical experiments suggested other qualities of matter, such as "oiliness" and "sulphurousness", or inflammability and salinity, which were not readily explained by the traditional fire, water, earth, and air division of elements.

Razi's challenge to the current fundamentals of medical theory was quite controversial. Many accused him of ignorance and arrogance, even though he repeatedly expressed his praise and gratitude to Galen for his contributions and labors, saying:

I prayed to God to direct and lead me to the truth in writing this book. It grieves me to oppose and criticize the man Galen from whose sea of knowledge I have drawn much. Indeed, he is the Master and I am the disciple. Although this reverence and appreciation will and should not prevent me from doubting, as I did, what is erroneous in his theories. I imagine and feel deeply in my heart that Galen has chosen me to undertake this task, and if he were alive, he would have congratulated me on what I am doing. I say this because Galen's aim was to seek and find the truth and bring light out of darkness. I wish indeed he were alive to read what I have published.[48]

- Crystallization of ancient knowledge, and the refusal to accept the fact that new data and ideas indicate that present day knowledge ultimately might surpass that of previous generations.

Razi believed that contemporary scientists and scholars are by far better equipped, more knowledgeable, and more competent than the ancient ones, due to the accumulated knowledge at their disposal. Razi's attempt to overthrow blind acceptance of the unchallenged authority of ancient sages encouraged and stimulated research and advances in the arts, technology, and sciences.

- The Diseases of Children

Razi's The Diseases of Children was the first monograph to deal with pediatrics as an independent field of medicine.[16][17]

- Mental health

As many other theorists in his time of exploration of illnesses, he believed that mental illnesses were caused by demons. Demons were believed to enter the body and possess the body.

Books on medicine

This is a partial list of Razi's books and articles in medicine, according to Ibn Abi Usaybi'ah. Some books may have been copied or printed under different names.

- al-Hawi (Arabic الحاوي), al-Hawi al-Kabir (الحاوي الكبير). Also known as The Virtuous Life, Continens Liber. The large medical Encyclopedia containing mostly recipes and Razi's notebooks.

- Isbate Elme Pezeshki (Persian اثبات علم پزشكى), ("Proving the Science of Medicine").

- Dar Amadi bar Elme Pezeshki (Persian در آمدى بر علم پزشكى) ("An Introduction to the Science of Medicine").

- Radde mnāqeḍāt al-ṭeb - mnāqeḍāt al-ṭeb was a work of ālǧāḥẓ which Razi was against his idea

- Radde Naghzat ot-tebb-e Nashi

- The Experimentation of Medical Science and its Application

- Guidance

- Kenash

- The Classification of Diseases

- Royal Medicine

- For One Without a Doctor (Arabic من لايحضره الطبيب)

- The Book of Simple Medicine

- The Great Book of Krabadin

- The Little Book of Krabadin

- The Book of Taj or The Book of the Crown

- The Book of Disasters

- Food and its Harmfulness

- al-Judari wa al-Hasbah, Translation: A treatise on the Small-pox and Measles[49]

- Ketab dar Padid Amadaneh Sangrizeh (Persian كتاب در پديد آمدن سنگريزه) ("The Book of Formation of small stones (Stones in the Kidney and Bladder)")

- Ketabeh Darde Roodeha (Persian كتاب درد رودهها) ("The Book of Pains in the Intestines")

- Ketab dar Darde Paay va Darde Peyvandhayye Andam (Persian كتاب در درد پاى و درد پيوندهاى اندام) ("The Book of Pains in Feet/Legs and Pains in Limbs' joints")

- Ketab dar Falej

- The Book of Tooth Aches

- Dar Hey'ate Kabed (Persian در هيأت كبد) ("About the Liver")

- Dar Hey'ate Ghalb (Persian در هيأت قلب) ("About the Heart")

- About the Nature of Doctors

- About the Eardrum (Persian در هيأت پرده صماخ)

- Dar Rag Zadan (Persian در رگ زدن) ("About Handling Vessels")

- Al-Sadineh (About Pharmacy) (Persian کتاب صدینه)

- Ketabeh Ibdal

- Food For Patients

- Soodhaye Serkangabin (Persian سودهاى سركنگبين) or ("Benefits of Serkangabin)

- Darmanhaye Abneh

- The Book of Surgical Instruments

- The Book on Oil

- Fruits Before and After Lunch

- Book on Medical Discussion (with Jarir Tabib)

- Book on Medical Discussion II (with Abu Feiz)

- About the Menstrual Cycle

- Ghay Kardan or vomiting (Persian قى كردن)

- Snow and Medicine

- Snow and Thirst

- The Foot

- Fatal Diseases

- About Poisoning

- Hunger

- Soil in Medicine

- The Thirst of Fish

- Sleep Sweating

- Warmth in Clothing

- Spring and Disease

- Misconceptions of a Doctor's Capabilities

- The Social Role of Doctors

Translated Works

Razi's notable books and articles on medicine (in English) include:

- Mofid al Khavas, The Book for the Elite.

- The Book of Experiences

- The Cause of the Death of Most Animals because of Poisonous Winds

- The Physicians' Experiments

- The Person Who Has No Access to Physicians

- The Big Pharmacology

- The Small Pharmacology

- Gout

- Al Shakook ala Jalinoos, The Doubt on Galen

- Kidney and Bladder Stones

- Ketab tibb ar-Ruhani, The Spiritual Physik of Rhazes.

Alchemy

The transmutation of metals

Razi's interest in alchemy and his strong belief in the possibility of transmutation of lesser metals to silver and gold was attested half a century after his death by Ibn an-Nadim's book (The Philosophers Stone-Lapis Philosophorum in Latin). Nadim attributed a series of twelve books to Razi, plus an additional seven, including his refutation to al-Kindi's denial of the validity of alchemy. Al-Kindi (801–873 CE) had been appointed by the Abbasid Caliph Ma'mum founder of Baghdad, to 'the House of Wisdom' in that city, he was a philosopher and an opponent of alchemy. Razi's two best-known alchemical texts, which largely superseded his earlier ones: al-Asrar (الاسرار "The Secrets"), and Sirr al-Asrar (سر الاسرار "The Secret of Secrets"), which incorporates much of the previous work.

Apparently Razi's contemporaries believed that he had obtained the secret of turning iron and copper into gold. Biographer Khosro Moetazed reports in Mohammad Zakaria Razi that a certain General Simjur confronted Razi in public, and asked whether that was the underlying reason for his willingness to treat patients without a fee. "It appeared to those present that Razi was reluctant to answer; he looked sideways at the general and replied":

I understand alchemy and I have been working on the characteristic properties of metals for an extended time. However, it still has not turned out to be evident to me, how one can transmute gold from copper. Despite the research from the ancient scientists done over the past centuries, there has been no answer. I very much doubt if it is possible...

According to one legend he could have been blinded by steaming vapors during an accident in one of his experiments. He managed to escape with no injuries.[50]

Chemical instruments and substances

Razi developed several chemical instruments that remain in use to this day. He is known to have perfected methods of distillation to gain alcohol[13] and extraction. ar-Razi dismissed the idea of potions and dispensed with magic, meaning the reliance on symbols as causes. Although Razi does not reject the idea that miracles exist, in the sense of unexplained phenomena in nature, his alchemical stockroom was enriched with products of Persian mining and manufacturing, even with sal ammoniac, a Chinese discovery. He relied predominantly on the concept of 'dominant' forms or essences, which is the Neoplatonic conception of causality rather than an intellectual approach or a mechanical one.[51] Razi's alchemy brings forward such empiric qualities as salinity and inflammability -the latter associated to 'oiliness' and 'sulphurousness'. These properties are not readily explained by the traditional composition of the elements such as: fire, water, earth and air, as al-óhazali and others after him were quick to note, influenced by critical thoughts such as Razi had.

Major works on alchemy

Razi's works present the first systematic classification of carefully observed and verified facts regarding chemical substances, reactions and apparatus, described in a language almost entirely free from mysticism and ambiguity.

- The Secret (Al-Asrar)

- This book was written in response to a request from Razi's close friend, colleague, and former student, Abu Mohammed b. Yunis of Bukhara, a Muslim mathematician, philosopher, and natural scientist.

In his book Sirr al-Asrar, Razi divides the subject of "Matter' into three categories, as in his previous book al-Asrar.- Knowledge and identification of the medical components within substances derived from plants, animals and minerals, and descriptions of the best types for medical treatments.

- Knowledge of equipment and tools of interest to and used by either alchemists or apothecaries.

- Knowledge of seven alchemical procedures and techniques: sublimation and condensation of mercury, precipitation of sulphur, and arsenic calcination of minerals (gold, silver, copper, lead, and iron), salts, glass, talc, shells, and waxing.

- This book was written in response to a request from Razi's close friend, colleague, and former student, Abu Mohammed b. Yunis of Bukhara, a Muslim mathematician, philosopher, and natural scientist.

- This last category contains additional descriptions of other methods and applications used in transmutation:

* The added mixture and use of solvent vehicles.

* The amount of heat (fire) used, 'bodies and stones', ('al-ajsad' and 'al-ahjar) that can or cannot be transmuted into corporal substances such of metals and Id salts ('al-amlah').

* The use of a liquid mordant which quickly and permanently colors lesser metals for more lucrative sale and profit. - Similar to the commentary on the 8th century text on amalgams ascribed to Al- Hayan (Jabir), Razi gives methods and procedures of coloring a silver object to imitate gold (gold leafing) and the reverse technique of removing its color back to silver. Gilding and silvering of other metals (alum, calcium salts, iron, copper, and tutty) are also described, as well as how colors will last for years without tarnishing or changing.

- This last category contains additional descriptions of other methods and applications used in transmutation:

- Razi classified minerals into six divisions:

- Four spirits (AL-ARWAH) : mercury, sal ammoniac, sulfur, and arsenic sulphide (orpiment and realgar).

- Seven bodies (AL-AJSAD) : silver, gold, copper, iron, black lead (plumbago), zinc (Kharsind), and tin.

- Thirteen stones : (AL-AHJAR) Pyrites marcasite (marqashita), magnesia, malachite, tutty Zinc oxide (tutiya), talcum, lapis lazuli, gypsum, azurite, magnesia, haematite (iron oxide), arsenic oxide, mica and asbestos and glass (then identified as made of sand and alkali of which the transparent crystal Damascene is considered the best),

- Seven vitriols (AL-ZAJAT) : alum (al-shabb الشب), and white (qalqadis القلقديس), black, red (suri السوري), and yellow (qulqutar القلقطار) vitriols (the impure sulfates of iron, copper, etc.), green (qalqand القلقند).

- Seven borates : natron, and impure sodium borate.

- Eleven salts (AL-AMLAH): including brine, common (table) salt, ashes, naphtha, live lime, and urine, rock, and sea salts. Then he separately defines and describes each of these substances, the best forms and colours of each, and the qualities of various adulterations.

- Razi gives also a list of apparatus used in alchemy. This consists of 2 classes:

- Instruments used for the dissolving and melting of metals such as the Blacksmith's hearth, bellows, crucible, thongs (tongue or ladle), macerator, stirring rod, cutter, grinder (pestle), file, shears, descensory and semi-cylindrical iron mould.

- Utensils used to carry out the process of transmutation and various parts of the distilling apparatus: the retort, alembic, shallow iron pan, potters kiln and blowers, large oven, cylindrical stove, glass cups, flasks, phials, beakers, glass funnel, crucible, alundel, heating lamps, mortar, cauldron, hair-cloth, sand- and water-bath, sieve, flat stone mortar and chafing-dish.

- Secret of Secrets (Sirr Al-asrar)

- This is Razi's most famous book. Here he gives systematic attention to basic chemical operations important to the history of pharmacy.

Books on alchemy

Here is a list of Razi's known books on alchemy, mostly in Persian:

- Modkhele Taalimi

- Elaleh Ma'aaden

- Isbaate Sanaa'at

- Ketabeh Sang

- Ketabe Tadbir

- Ketabe Aksir

- Ketabe Sharafe Sanaa'at

- Ketabe Tartib, Ketabe Rahat, The Simple Book

- Ketabe Tadabir

- Ketabe Shavahed

- Ketabe Azmayeshe Zar va Sim (Experimentation on Gold)

- Ketabe Serre Hakimaan

- Ketabe Serr (The Book of Secrets)

- Ketabe Serre Serr (The Secret of Secrets)

- The First Book on Experiments

- The Second Book on Experiments

- Resaale'ei Be Faan

- Arezooyeh Arezookhah

- A letter to Vazir Ghasem ben Abidellah

- Ketabe Tabvib

Philosophy

Metaphysics

The metaphysical doctrine of Razi derives from the theory of the "five eternals", according to which the world is produced out of an interaction between God and four other eternal principles (soul, matter, time, and place).[52] He accepted a pre-socratic type of atomism of the bodies, and for that he differed from both the falasifa and the mutakallimun.[52] While he was influenced by Plato and the medical writers, mainly Galen, he rejected taqlid and thus expressed criticism about some of their views. This is evident from the title of one of his works, Doubts About Galen.[52]

Excerpt from The Philosophical Approach

(...) In short, while I am writing the present book, I have written so far around 200 books and articles on different aspects of science, philosophy, theology, and hekmat (wisdom). (...) I never entered the service of any king as a military man or a man of office, and if I ever did have a conversation with a king, it never went beyond my medical responsibility and advice. (...) Those who have seen me know, that I did not into excess with eating, drinking or acting the wrong way. As to my interest in science, people know perfectly well and must have witnessed how I have devoted all my life to science since my youth. My patience and diligence in the pursuit of science has been such that on one special issue specifically I have written 20,000 pages (in small print), moreover I spent fifteen years of my life -night and day- writing the big collection entitled Al Hawi. It was during this time that I lost my eyesight, my hand became paralyzed, with the result that I am now deprived of reading and writing. Nonetheless, I've never given up, but kept on reading and writing with the help of others. I could make concessions with my opponents and admit some shortcomings, but I am most curious what they have to say about my scientific achievement. If they consider my approach incorrect, they could present their views and state their points clearly, so that I may study them, and if I determined their views to be right, I would admit it. However, if I disagreed, I would discuss the matter to prove my standpoint. If this is not the case, and they merely disagree with my approach and way of life, I would appreciate they only use my written knowledge and stop interfering with my behaviour.

In the Philosophical Biography, as seen above, he defended his personal and philosophical life style. In this work he laid out a framework based on the idea that there is life after death full of happiness, not suffering. Rather than being self-indulgent, man should pursue knowledge, utilise his intellect and apply justice in his life.

According to Al-Razi: "This is what our merciful Creator wants. The One to whom we pray for reward and whose punishment we fear."

In brief, man should be kind, gentle and just. Al-Razi believed that there is a close relationship between spiritual integrity and physical health. He did not implicate that the soul could avoid distress due to his fear of death. He simply states that this psychological state cannot be avoided completely unless the individual is convinced that, after death, the soul will lead a better life. This requires a thorough study of esoteric doctrines and/or religions. He focuses on the opinion of some people who think that the soul perishes when the body dies. Death is inevitable, therefore one should not pre-occupy the mind with it, because any person who continuously thinks about death will become distressed and think as if he is dying when he continuously ponders on that subject. Therefore, he should forget about it in order to avoid upsetting himself. When contemplating his destiny after death, a benevolent and good man who acts according to the ordinances of the Islamic Shari`ah, has after all nothing to fear because it indicates that he will have comfort and permanent bliss in the Hereafter. The one who doubts the Shari`ah, may contemplate it, and if he diligently does this, he will not deviate from the right path. If he falls short, Allah will excuse him and forgive his sins because it is not demanded of him to do something which he cannot achieve.

- —Dr. Muhammad Abdul-Hadi Abu Reidah

Books on philosophy

This is a partial list of Razi's books on philosophy. Some books may have been copied or published under different titles.

- The Small Book on Theism

- Response to Abu'al'Qasem Braw

- The Greater Book on Theism

- Modern Philosophy

- Dar Roshan Sakhtane Eshtebaah

- Dar Enteghaade Mo'tazlian

- Delsoozi Bar Motekaleman

- Meydaneh Kherad

- Khasel

- Resaaleyeh Rahnamayeh Fehrest

- Ghasideyeh Ilaahi

- Dar Alet Afarineshe Darandegan

- Shakkook

- Naghseh Ketabe Tadbir

- Naghsnamehyeh Ferforius

- Do name be Hasanebne Moharebe Ghomi

Notable books in English:

- Spiritual Medicine

- The Philosophical Approach (Al Syrat al Falsafiah)

- The Metaphysics

Chess

Al-Rāzī was a chess rival of al-‘Adlī and the Abbāsid caliph al-Mutawakkil attended their matches. Al-Nadīm lists al-Rāzī among a group of five authors of books on Shiṭranj (Chess) or Al-nard,[n 1] who were: Abū Bakr al-Ṣūlī, Al-‘Adlī, Abū al-Faraj al-Lajlāj and Ibn al-Uqlīdasī. The title of al-Rāzī's book was:

Views on religion

A number of contradictory works and statements about religion have been ascribed to Razi. According to al-Biruni's Bibliography of Razi (Risāla fī Fihrist Kutub al-Rāzī), Razi wrote two "heretical books": "Fī al-Nubuwwāt (On Prophecies) and "Fī Ḥiyal al-Mutanabbīn (On the Tricks of False Prophets). According to Biruni, the first "was claimed to be against religions" and the second "was claimed as attacking the necessity of the prophets."[55] In his Risala, Biruni further criticized and expressed caution about Razi's religious views, noting an influence of Manichaeism. However, Biruni also listed some other works of Razi on religion, including Fi Wujub Da‘wat al-Nabi ‘Ala Man Nakara bi al-Nubuwwat (Obligation to Propagate the Teachings of the Prophet Against Those who Denied Prophecies) and Fi anna li al-Insan Khaliqan Mutqinan Hakiman (That Man has a Wise and Perfect Creator), listed under his works on the "divine sciences".[55] None of his works on religion are now extant in full.

Other views and quotes that are often ascribed to Razi are found in a book written by Abu Hatim al-Razi, called Aʿlām al-nubuwwa (Signs of Prophecy), and not in any extant work of Razi himself. Abu Hatim was an Isma'ili missionary who debated Razi, but whether he has faithfully recorded the views of Razi is disputed.[52] According to Abdul Latif al-'Abd, Islamic philosophy professor at Cairo University, Abu Hatim and his student, Ḥamīd al-dīn Karmānī (d. after 411AH/1020CE), were Isma'ili extremists who often misrepresented the views of Razi in their works.[56][57] This view is also corroborated by early historians like al-Shahrastani who noted "that such accusations should be doubted since they were made by Ismāʿīlīs, who had been severely attacked by Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyā Rāzī".[58] Al-'Abd points out that the views allegedly expressed by Razi contradict what is found in Razi's own works, like the Spiritual Medicine (Fī al-ṭibb al-rūḥānī).[56] Peter Adamson concurs that Abu Hatim may have "deliberately misdescribed" Razi's position as a rejection of Islam and revealed religions. Instead, Razi was only arguing against the use of miracles to prove Muhammad's prophecy, anthropomorphism, and the uncritical acceptance of taqlīd vs naẓar.[52] Adamson points out to a work by Fakhr al-din al-Razi where Razi is quoted as citing the Quran and the prophets to support his views.[52]

Some historians, such as Paul Kraus and Sarah Stroumsa, accept that the extracts found in Abu Hatim's book were either said by Razi during a debate or were quoted from a now lost work. They suggest that this lost work is either his famous al-ʿIlm al-Ilāhī or another shorter independent work called Makharīq al-Anbiyāʾ (The Prophets' Fraudulent Tricks).[59][60] Abu Hatim, however, did not explicitly mention Razi by name in his book, but referred to his interlocutor simply as the mulḥid (lit. "heretic").[52][56] According to the debate with Abu Hatim, Razi denied the validity of prophecy or other authority figures, and rejected prophetic miracles. He also directed a scathing critique on revealed religions and the miraculous quality of the Quran.[52][61] Because of being seemingly unrestrained by any religious or philosophical tradition, Razi came to be admired as a freethinker by some.[52]

Criticism

Al-Razi's religious and philosophical views were later criticized by Abu Rayhan Biruni and Avicenna in the early 11th century. Biruni in particular wrote a short treatise (risala) dealing with al-Razi, criticizing him for his sympathy with Manichaeism,[62] his Hermetical writings, his religious and philosophical views,[63] for refusing to mathematize physics, and his active opposition to mathematics.[64] Avicenna, who was himself a physician and philosopher, also criticized al-Razi.[65] During a debate with Biruni, Avicenna stated:

Or from Muhammad ibn Zakariyyab al-Razi, who meddles in metaphysics and exceeds his competence. He should have remained confined to surgery and to urine and stool testing—indeed he exposed himself and showed his ignorance in these matters.[66]

Nasr-i-Khosraw posthumously accused him of having plagiarized Iranshahri, who Khosraw considered as the master of al-Razi.[67]

Legacy

.jpg)

The modern-day Razi Institute in Karaj and Razi University in Kermanshah were named after him. A "Razi Day" ("Pharmacy Day") is commemorated in Iran every 27 August.[68]

In June 2009, Iran donated a "Scholars Pavilion" or Chartagi to the United Nations Office in Vienna, now placed in the central Memorial Plaza of the Vienna International Center.[69] The pavilion features the statues of Razi, Avicenna, Abu Rayhan Biruni, and Omar Khayyam.[70][71]

George Sarton remarked him as "greatest physician of Islam and the Medieval Ages".[72]

While The Bulletin of the World Health Organization (May 1970) noted that his "writings on smallpox and measles show originality and accuracy, and his essay on infectious diseases was the first scientific treatise on the subject".

See also

- List of Iranian scientists

- Medical Encyclopedia of Islam and Iran

- Medical literature

Notes

- Pathfinders: (ISBN 978-1-84614-161-4)

- Iskandar, Albert (2006). "Al-Rāzī". Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 155–156.

- "Rhazes". American Heritage Dictionary.

- Hitti, Philip K. (1977). History of the Arabs from the earliest times to the present (10th ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-333-09871-4.

The most notable medical authors who followed the epoch of the great translators were Persian in nationality but Arab in language: 'Ali al-Tabari, al-Razi, 'Ali ibn-al-'Abbas al-Majusi and ibn-Sina.

- Robinson, Victor (1944), The story of medicine, New York: New Home Library

- Porter, Dorothy (2005), Health, civilization, and the state: a history of public health from ancient to modern times, New York: Routledge (published 1999), p. 25, ISBN 978-0-415-20036-3

- Majid Fakhry, A History of Islamic Philosophy: Third Edition, Columbia University Press (2004), p. 98

- Hakeem Abdul Hameed, Exchanges between India and Central Asia in the field of Medicine

- Iskandar, Albert (2006). "Al-Rāzī". Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 155–156.

- Influence of Islam on World Civilization" by Prof. Z. Ahmed, p. 127.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā, Fuat Sezgin, Māzin ʻAmāwī, Carl Ehrig-Eggert, and E. Neubauer. Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyāʼ ar-Rāzī (d. 313/925): texts and studies. Frankfurt am Main: Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, 1999.

- "Handbook to Life in the Medieval World, 3-Volume Set", by Madeleine Pelner Cosman, Linda Gale Jones, page = 52, ISBN 9781438109077, publisher = Infobase Publishing

- Modanlou, H. D. (2008). "A tribute to Zakariya Razi (865 - 925 AD), an Iranian pioneer scholar". Archives of Iranian Medicine. PubMed. 11 (6): 673–7. PMID 18976043.

- "Distillation – from Bronze Age till today".

- Browne (2001, p. 44)

- Tschanz David W., PhD (2003). "Arab(?) Roots of European Medicine". Heart Views. 4 (2).

- Elgood, Cyril (2010). A Medical History of Persia and The Eastern Caliphate (1st ed.). London: Cambridge. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-1-108-01588-2.

By writing a monograph on 'Diseases in Children' he may also be looked upon as the father of paediatrics.

- "Ar-Razi (Rhazes), 864-930 C.E." www.unhas.ac.id. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

Ar-Razi was a pioneer in many areas of medicine and treatment and the health sciences in general. In particular, he was a pioneer in the fields of pediatrics, obstetrics and ophthalmology.

- Richter-Bernburg

- Boyce, Mary; Frantz, Grenet (1982). History of Zoroastrianism: Under The Achaemenians. Leiden: Brill. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-04-06506-2. (See also the following excerpt: "the question of the identification of Avestan Raya with the Raga in the inscription of Darius I at Bīsotūn [...] with Ray[...] has by no means been settled".Gnoli, Gerardo (1982). "Avestan geography". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 3. ISBN 978-0-7100-9121-5.)

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā. "The Book of Medicine Dedicated to Mansur and Other Medical Tracts – Liber ad Almansorem". World Digital Library (in Latin). Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā. "The Book on Medicine Dedicated to al-Mansur – الكتاب المنصوري في الطب". World Digital Library (in Amharic and Arabic). Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Commentary on the Chapter Nine of the Book of Medicine Dedicated to Mansur – Commentaria in nonum librum Rasis ad regem Almansorem". World Digital Library (in Latin). 1542. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Nikaein F, Zargaran A, Mehdizadeh A (2012). "Rhazes' concepts and manuscripts on nutrition in treatment and health care". Anc Sci Life. 31 (4): 160–3. doi:10.4103/0257-7941.107357. PMC 3644752. PMID 23661862.

- Magner, Lois N. A History of Medicine. New York: M. Dekker, 1992, p. 140.

- Magner, Lois N. (13 August 2002). A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded. CRC Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8247-4360-4.

- Pococke, E. Historia Compendosia Dynastiarum. Oxford, 1663, p. 291.

- Long, George (1841). The Penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, Volume 19. C. Knight. p. 445.

rhazes.

- "Saab Medical Library – كتاب في الجدري و الحصبة – American University of Beirut". Ddc.aub.edu.lb. 1 June 2003. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997, p. 97.

- Kamiar, Mohammad. Brilliant Biruni: A Life Story of Abu Rayhan Mohammad Ibn Ahmad. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press, 2009.

- Ruska, Julius. Al-Birūni als Quelle für das Leben und die Schriften al-Rāzi's. Bruxelles: Weissenbruch, 1922.

- Joseph Needham; Ling Wang (1954). 中國科學技術史. Cambridge University Press. pp. 219–. ISBN 978-0-521-05799-8.

- Jacques Gernet (31 May 1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- غليزان, فيزياء. "الرازي". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "قلم لنكبرده ولساكسه , قلم الصين". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Gunton, Simon. The History of the Church of Peterborough. London, Richard Chiswell, publisher, 1686. Facsimile edition published by Clay, Tyas, and Watkins in Peterborough and Stamford (1990). Item Fv. on pp. 187–8.

- Phipps, Claude (5 October 2015). No Wonder You Wonder!: Great Inventions and Scientific Mysteries. Springer. p. 111. ISBN 9783319216805.

- Hashempur, Mohammad Hashem; Hashempour, Mohammad Mahdi; Mosavat, Seyed Hamdollah; Heydari, Mojtaba (2017). "Rhazes-His Life and Contributions to the Field of Dermatology". JAMA Dermatology. 153 (1): 70. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0144. PMID 28114524.

- Fuat Sezgin (1970). Ar-Razi. In: Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums Bd. III: Medizin – Pharmazie – Zoologie – Tierheilkunde = History of the Arabic literature Vol. III: Medicine – Pharmacology – Veterinary Medicine. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 276, 283.

- Evans, Imogen; Thornton, Hazel; Chalmers, Iain; Glasziou, Paul (1 January 2011). Testing Treatments: Better Research for Better Healthcare (2nd ed.). London: Pinter & Martin. ISBN 9781905177486. PMID 22171402.

- "The valuable contributions of Al-Razi (Rhazes) in the history of pharmacy during the middle ages". Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Islamic Science, the Scholar and Ethics Archived 22 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā. "The Comprehensive Book on Medicine – كتاب الحاوى فى الطب". World Digital Library. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "The Comprehensive Book on Medicine – كتاب الحاوي". World Digital Library (in Arabic). 1674 [Around 1674 CE]. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Rāzī, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakarīyā (1529). "The Comprehensive Book on Medicine—Continens Rasis". World Digital Library (in Latin). Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Emilie Savage-Smith (1996), "Medicine", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 3, pp. 903–962 [917]. Routledge, London and New York.

- Bashar Saad, Omar Said, Greco-Arab and Islamic Herbal Medicine: Traditional System, Ethics, Safety, Efficacy, and Regulatory Issues, John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 9781118002261, page

- A Treatise on the Small-pox and Measles, Translated by William Alexander Greenhill, Published by Printed for the Sydenham Society [by C and J. Adlrd], 1848, pp. 252, URL

- M. Th. Houtsma, ed. (1993). E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. 4. Brill. p. 1101. ISBN 978-90-04-09790-2.

- Waines, David (2010). Food Culture and Health in Pre-Modern Muslim Societies. BRILL. pp. 225. ISBN 9789004194410.

- Marenbon, John (14 June 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Philosophy. Oxford University Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9780195379488.

- Nadīm (al), Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq Abū Ya’qūb al-Warrāq (1970). Dodge, Bayard (ed.). The Fihrist of al-Nadim; a tenth-century survey of Muslim culture. i. New York & London: Columbia University Press. p. 341.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nadīm (al-), Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq (1872). Flügel, Gustav (ed.). Kitāb al-Fihrist (in Arabic). Leipzig: F.C.W. Vogel. p. 567 (p.155).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Deuraseh, Nurdeng (2008). "Risalat Al-Biruni Fi Fihrist Kutub Al-Razi: A Comprehensive Bibliography of the Works of Abu Bakr Al-Rāzī (d. 313 A.h/925) and Al-Birūni (d. 443/1051)". Journal of Aqidah and Islamic Thought. 9: 51–100.

- Abdul Latif Muhammad al-Abd (1978). Al-ṭibb al-rūḥānī li Abū Bakr al-Rāzī. Cairo: Maktabat al-Nahḍa al-Miṣriyya. pp. 4, 13, 18.

- Ebstein, Michael (25 November 2013). Mysticism and Philosophy in al-Andalus: Ibn Masarra, Ibn al-ʿArabī and the Ismāʿīlī Tradition. BRILL. p. 41. ISBN 9789004255371.

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr, and Mehdi Amin Razavi, An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, vol. 1, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 353, quote: "Among the other eminent figures who attacked Rāzī are the Ismāʿīlī philosopher Abū Ḥatem Rāzī, who wrote two books to refute Rāzī's views on theodicy, prophecy, and miracles; and Nāṣir-i Khusraw. Shahrastānī, however, indicates that such accusations should be doubted since they were made by Ismāʿīlīs, who had been severely attacked by Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyā Rāzī"

- Sarah Stroumsa (1999). Freethinkers of Medieval Islam: Ibn Al-Rawandi, Abu Bakr Al-Razi and Their Impact on Islamic Thought. Brill.

- Kraus, P; Pines, S (1913–1938). "Al-Razi". Encyclopedia of Islam. p. 1136.

- Paul E. Walker (1992). "The Political Implications of Al-Razi's Philosophy". In Charles E. Butterworth (ed.). The Political aspects of Islamic philosophy: essays in honor of Muhsin S. Mahdi. Harvard University Press. pp. 87–89.

- William Montgomery Watt (14 April 2004). "BĪRŪNĪ and the study of non-Islamic Religions". Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2008.

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr (1993), An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines, p. 166. State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-1516-3.

- Shlomo Pines (1986), Studies in Arabic versions of Greek texts and in mediaeval science, 2, Brill Publishers, p. 340, ISBN 978-965-223-626-5

- Shlomo Pines (1986), Studies in Arabic versions of Greek texts and in mediaeval science, 2, Brill Publishers, p. 362, ISBN 978-965-223-626-5

- Rafik Berjak and Muzaffar Iqbal, "Ibn Sina—Al-Biruni correspondence", Islam & Science, December 2003.

- Corbin, Henry (1998). The Voyage and the Messenger: Iran and Philosophy. North Atlantic Books. p. 72. ISBN 9781556432699.

Al-Razi was posthumously accused of having plagiarized his master in Nasr-i-Khosraw polemics, and the latter did not hide his sympathy for Iranshahri.

- qhu.ac.ir, Razi commemoration day

- UNIS. "Monument to Be Inaugurated at the Vienna International Centre, 'Scholars Pavilion' donated to International Organizations in Vienna by Iran".

- "Permanent mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations office - Vienna". Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Hosseini, Mir Masood. "Negareh: Persian Scholars Pavilion at United Nations Vienna, Austria".

- George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science (1927–48), 1.609

- Al-nard or nardashīr resembled modern board game of checkers or backgammon.

References

- Browne, Edward Granville (2001). Islamic Medicine. Goodword Books Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-87570-19-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richter-Bernburg, Lutz. "AL-ḤĀWI". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 1. ISBN 978-0-933273-54-2.

Further reading

Primary literature

By Razi

- Arberry, A.J. (1950). The Spiritual Physick of Rhazes. The Wisdom of the East Series.

- See C. Brockelmann for the manuscript of Razi's extant books in general, see Brockelmann, Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur, I, pp. 268–71 (second edition), Suppl., Vol. I, pp. 418–21.

- Paul Kraus, Abi Bakr Mohammadi Filii Zachariae Raghensis: Opera Philosophica, fragmentaque quae superssunt. Pars Prior. Cairo 1939

- Abdul Latif Muhammad al-Abd (1978). Al-ṭibb al-rūḥānī li Abū Bakr al-Rāzī. Cairo: Maktabat al-Nahḍa al-Miṣriyya.

- Charles E. Butterworth, "The Book of the Philosophic Life". Interpretation: A Journal of Political Philosophy.

By others

- Ibn Al-Nadim, Fihrist, (ed. Flugel), pp. 299 et sqq.

- Sa'id al-Andalusi, Tabaqat al-Umam, p. 33

- Ibn Juljul, Tabaqat al-Atibba w-al-Hukama, (ed. Fu'ad Sayyid), Cairo, 1355/1936, pp. 77–78

- J. Ruska, Al-Biruni als Quelle fur das Leben und die Schriften al-Razi's, Isis, Vol. V, 1924, pp. 26–50.

- Al-Biruni, Epitre de Beruni, contenant le repertoire des ouvres de Muhammad ibn Zakariya ar-Razi, publiee par P. Kraus, Paris, 1936

- Al-Baihaqi, Tatimmah Siwan al-Hikma, (ed. M. Ghafi), Lahore, 1351/1932

- Al-Qifti,Tarikh al-Hukama, (ed. Lippert), pp. 27–177

- Ibn Abi Usaibi'ah,Uyun al-Anba fi Tabaqat al-Atibba, Vol. I, pp. 309–21

- Abu Al-Faraj ibn al-'Ibri (Bar-Hebraeus),Mukhtasar Tarikh al-Duwal, (ed. A. Salhani), p. 291

- Ibn Khallikan, Wafayat al-A'yan, (ed. Muhyi al-Din 'Abd al-Hamid), Cairo, 1948, No. 678, pp. 244–47

- Al-Safadi, Nakt al-Himyan, pp. 249–50

- Ibn al-'Imad, Shadharat al-Dhahab, Vol. II, p. 263

- Al-'Umari, Masalik al-Absar, Vol. V, Part 2, ff. 301-03 (photostat copy in Dar al-Kutub al-Misriyyah).

Secondary literature

- G. S. A. Ranking, The Life and Works of Rhazes, in Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Congress of Medicine, London, 1913, pp. 237–68.

- Al-Razi als Bahnbrecher einer neuer Chemie, Deutsche Literaturzeitung, 1923, pp. 118–24.

- Die Alchemie al-Razi's der Islam, Vol. XXII, pp. 283–319.

- Uber den gegenwartigen Stand der Razi-Forschung, Archivio di stori della scienza, 1924, Vol. V, pp. 335–47

- H. H. Shader, ZDMG, 79, pp. 228–35 (see translation into Arabic by Abdurrahman Badawi in al-Insan al-Kamil, Islamica, Vol. XI, Cairo, 1950, pp. 37–44).

- E. O. von Lippmann, Entstehung und Ausbreitung der Alchemie, Vol. II, p. 181.

- S. Pines, Die Atomenlehre ar-Razi's in Beitrage zur islamischen Atomenlehre, Berlin, 1936, pp. 34–93.

- Dr. Mahmud al-Najmabadi, Shah Hal Muhammad ibn Zakariya, (1318/1900)

- Gamil Bek, Uqud al-Jauliar, Vol. I, pp. 118–27.

- Izmirli Haqqi, Ilahiyat, Fak. Macm., Vol. I, p. 151; Vol. II, p. 36, Vol. III, pp. 177 et seq.

- Abdurrahman Badawi, Min Tarlkh al-Ilhad fi al-Islam Islamica, Vol. II, Cairo, 1945, pp. 198–228.

- Hirschberg,Geschichte der Augenheilkunde, p. 101.

- E. G.Browne, Arabian Medicine, Cambridge, 1921, pp. 44–53.

- M. Meyerhof, Legacy of Islam, pp. 323 et seq.

- F. Wüstenfeld, Geschichte der Arabischen Arzte und Naturforscher, ftn. 98.

- L. Leelerc, Histoire de la medicine arabe, Paris, 1876, Vol. I, pp. 337–54.

- H. P. J. Renaud, A propos du millenaire de Razes, in bulletin de la Societe Irancaise d'Histoire de la medicine, Mars-avril, 1931, pp. 203 et seq.

- A. Eisen, Kimiya al-Razi, RAAD, DIB, 62/4.

- Aldo Mieli, La science arabe, Leiden, 1938, pp. 8, 16.

- Nasr, Science and Civilization in Islam, see. Razes: The Secret of Secrets, p. 273, also pp. 197–200, and Anawati: L'Alchemie arabe in Rased.

- Browne, Edward Granville (2001). Islamic Medicine. Goodword Books Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-87570-19-6.

- M. M. Sharif, A History of Muslim Philosophy

- Walker, P. "The Political Implications of al-Razi's Philosophy", in C. Butterworth (ed.) The Political Aspects of Islamic Philosophy, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 61–94. (1992)

- Motazed, K. Mohammad Zakaria Razi

- Oliver Kahl (31 March 2015). The Sanskrit, Syriac and Persian Sources in the Comprehensive Book of Rhazes. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-29024-2.

- Denyse Rockey and Penelope Johnstone, "Medieval Arabic views on speech disorders: Al-Razi (c. 865–925)", in: Journal of Communication Disorders, 12(3):229-43, June 1979.

Encyclopedia

- Richter-Bernburg, Lutz. "AL-ḤĀWI". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 1. ISBN 978-0-933273-54-2.

- Encyclopaedie des Islams, s. v. (by Ruska).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi |

- "al-Razi" on Islamic Philosophy Online, encyclopedia article about al-Razi by Paul E. Walker.

- Lives of the Physicians, dating from 1882, features a biography, in Arabic, about Rhazes.