Montu

Montu was a falcon-god of war in ancient Egyptian religion, an embodiment of the conquering vitality of the pharaoh.[1] He was particularly worshipped in Upper Egypt and in the district of Thebes.[2]

[Ramesses II] whom victory was foretold as he came from the womb,

Whom valor was given while in the egg,

Bull firm of heart as he treads the arena,

Godly king going forth like Montu on victory day.

| Montu | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Name in hieroglyphs | ||||

| Major cult center | Hermonthis, Thebes, Medamud, El-Tod | |||

| Consort | Raet-Tawy, Tjenenyet, Iunit | |||

Name

Montu's name, shown in Egyptian hieroglyphs to the right, is technically transcribed as mntw (meaning "Nomad"[4][5]). Because of the difficulty in transcribing Egyptian vowels, it is often realized as Mont, Monthu, Montju, Ment or Menthu.[4]

Role and characteristics

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs |

|

Practices

|

|

Deities (list) |

|

Locations |

|

Symbols and objects

|

|

Related religions

|

|

|

A very ancient god, Montu was originally a manifestation of the scorching effect of Ra, the sun – and as such often appeared under the epithet Montu-Ra. The destructiveness of this characteristic led to him gaining characteristics of a warrior, and eventually becoming a widely revered war-god. The Egyptians thought that Montu would attack the enemies of Maat (that is, of the truth, of the cosmic order) while inspiring, at the same time, glorious warlike exploits.[6] It is possible that Montu-Ra and Atum-Ra symbolized the two kingships, respectively, of Upper and Lower Egypt.[7] When linked with Horus, Montu's epithet was "Horus of the Strong Arm".[8]

Because of the association of raging bulls with strength and war, the Egyptians also believed that Montu manifested himself as a white, black-snouted bull named Buchis (hellenization of the original Bakha: a living bull revered in Armant) — to the point that, in the Late Period (7th-4th centuries BC), Montu was depicted with a bull's head too.[2] This special sacred bull had dozens of servants and wore precious crowns and bibs.[7]

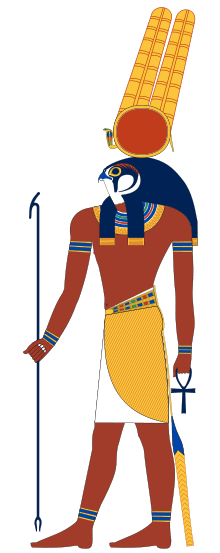

In Egyptian art, Montu was depicted as a falcon-headed or bull-headed man, with his head surmounted by the solar disk (because of his conceptual link with Ra[2]) and two feathers. The falcon was a symbol of the sky and the bull was a symbol of strength and war. He could also wield various weapons, such as a curved sword, a spear, bow and arrows, or knives: such military iconography was widespread in the New Kingdom (16th-11th centuries BC).[4]

Montu had several consorts, including the little-known Theban goddesses Tjenenyet[9] and Iunit,[10] and a female form of Ra, Raet-Tawy.[8] He was also revered as one of the patrons of the city of Thebes and its fortresses. The sovereigns of the 11th Dynasty (c. 2134–1991 BC) chose Montu as a protective and dynastic deity, inserting references to him in their own names. For example, four pharaohs of the 11th Dynasty were called Mentuhotep, which means "Montu (Mentu) is satisfied":

- Mentuhotep I (c. 2135 BC) — maybe a fictional figure;

- Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II (c. 2061–2010 BC);

- Sankhkare Mentuhotep III (c. 2010–1998 BC);

- Nebtawyre Mentuhotep IV (c. 1998–1991 BC).[1]

The Greeks associated Montu with their god of war Ares – although that did not prevent his assimilation to Apollo, probably due to the solar radiance that distinguished him.[4][8]

Montu and the pharaohs at war

The cult of this military god enjoyed great prestige under the pharaohs of the 11th Dynasty,[1] whose expansionism and military successes led, around 2055 BC, to the reunification of Egypt, the end of a period of chaos known today as the First Intermediate Period, and a new era of greatness for the country. This part of Egyptian history, known as the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC),[11] was a period in which Montu assumed the role of supreme god — before then gradually being surpassed by the other Theban god Amun, destined to become the most important deity of the Egyptian pantheon.[2]

From the 11th Dynasty onward, Montu was considered the symbol of the pharaohs as rulers, conquerors and winners, as well as their inspirer on the battlefield. The Egyptian armies were surmounted by the insignia of the "four Montu" (Montu of Thebes, of Armant, of Medamud, and of El-Tod: the main cult centers of the god), all represented while trampling and piercing enemies with a spear in a classic pugnacious pose.[6] A ceremonial battle ax, belonging to the funeral kit of Queen Ahhotep II, Great Royal Wife of the warlike pharaoh Kamose (c. 1555–1550 BC), who lived between the 17th and 18th Dynasty, represents Montu as a proud winged griffin: an iconography clearly influenced by the same Syriac origin which inspired Minoan art.[12]

Egypt's greatest general-kings called themselves "Mighty Bull", "Son Of Montu", "Montu Is with His Strong/Right Arm" (Montuherkhepeshef: which was also the given name of a son of Ramesses II, of one of Ramesses III and one of Ramesses IX). Thutmose III (c. 1479—1425 BC), "the Napoleon of Egypt",[13] was described in ancient times as a "Valiant Montu on the Battlefield".[4] An inscription from his son Amenhotep II (1427–1401 BC) recalls that the eighteen-year-old pharaoh was able to shoot arrows through copper targets while driving a war chariot, commenting that he had the skill and strength of Montu.[7] The latter's grandson, Amenhotep III the Magnificent (c.1388–1350 BC), called himself "Montu of the Rulers" in spite of his own peaceful reign.[14] In the narrative of the Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BC), Ramesses II the Great — who proudly called himself "Montu of the Two Lands"[4] — was said to have seen the enemy and "raged at them like Montu, Lord of Thebes".[15]

[...] his majesty passed the fortress of Tjaru, like Montu when he goes forth. Every country trembled before him, fear was in their hearts [...] The goodly watch in life, prosperity and health, in the tent of his majesty, was on the highland south of Kadesh. When his majesty appeared like the rising of Re, he assumed the adornments of his father, Montu. [...]

Temples

Medamud

The Temple complex of Montu in Medamud, the ancient Medu, less than five kilometers north-east of today's Luxor,[17] was built by the great Pharaoh Senusret III (c. 1878–1839 BC) of the 12th Dynasty, probably on a pre-existing sacred site of the Old Kingdom. The temple courtyard was used as a dwelling for the living Buchis bull, revered as an incarnation of Montu.[7] The main entrance was to the north-east, while a sacred lake was probably on the west side of the sanctuary. The building consisted of two distinct adjoining sections, perhaps a temple to the north and a temple to the south (houses of the priests). It was built in raw bricks, while the innermost cella of the deity was built of carved stone. The templar complex of Medamud underwent important restorations and renovations during the New Kingdom, and in the Ptolemaic and Roman period.[12]

Armant

_-_Views_in_Egypt_and_Nubia_-_n._357_-_The_Temple_of_Erment.jpg)

At Armant, the ancient Iuni, there was an impressive Temple of Montu at least since the 11th Dynasty, which may have been native of Armant. King Mentuhotep II is its first known builder, but the original complex was enlarged and embellished during the 12th Dynasty, the less well-known 13th Dynasty (c. 1803–1649 BC), and later in the New Kingdom (especially under King Thutmose III).[18] Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) and his son Merneptah (1213–1203 BC) of the 19th Dynasty added colossi and statues.[18] It was dismantled, except for a pylon, in the Late Period (7th/4th century BC) — but a new temple was begun by King Nectanebo II (360–342 BC), the last native pharaoh of Egypt, and continued by the Ptolemies. In the 1st century BC, Cleopatra VII (51–30 BC) built a mammisi and a sacred lake there in honour of her son, the very young Ptolemy XV Caesarion.[19] The building remained visible until 1861, when it was demolished to reuse its material in the construction of a sugar factory; however, etchings, prints and previous studies (for example the Napoleonic Description de l'Égypte) show its appearance. Only the remains of the pylon of Thutmose III are still visible — in addition to the ruins of two entrances, one of which was built under the 2nd century AD Roman emperor/Pharaoh Antoninus Pius. In the large Armant complex, moreover, there was the Bucheum, necropolis of the Buchis sacred bulls. The first burial of a Buchis in this special necropolis dates back to the reign of Nectanebo II (c. 340 BC), while the final one took place at the time of the Emperor/Pharaoh Diocletian (c. 300 AD).[12]

Karnak and Uronarti

In the great Karnak Temple Complex, north of the monumental Temple of Amun, King Amenhotep III built a sacred enclosure to Montu.[2][12] Another temple had been dedicated to him at the little-known fortress of Uronarti (near the Second Cataract of the Nile, specifically to the south of it) during the Middle Kingdom.

Gallery

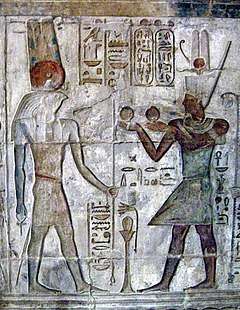

A coarse stela representing the warrior-Pharaoh Senusret III (1878–1839 BC) in the presence of Montu. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

A coarse stela representing the warrior-Pharaoh Senusret III (1878–1839 BC) in the presence of Montu. Egyptian Museum, Cairo..jpg)

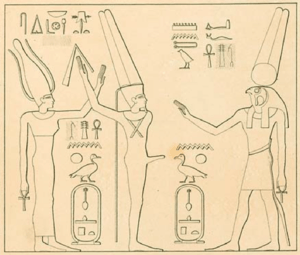

Drawing of a petroglyph in Konosso with the goddess Satis, the ithyphallic god Min, Montu and the cartouche of King Neferhotep I (c. 1747–1736 BC).

Drawing of a petroglyph in Konosso with the goddess Satis, the ithyphallic god Min, Montu and the cartouche of King Neferhotep I (c. 1747–1736 BC). Ruins of the Temple of Montu in Armant, published in The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia — after a watercolour by David Roberts (1849).

Ruins of the Temple of Montu in Armant, published in The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia — after a watercolour by David Roberts (1849). Ruins of the Temple of Montu in Medamud.

Ruins of the Temple of Montu in Medamud.

References

- Hart, George, A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Routledge, 1986, ISBN 0-415-05909-7. p. 126.

- Rachet, Guy (1994). Dizionario della civiltà egizia. Rome: Gremese Editore. ISBN 88-7605-818-4. p. 208.

- Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volume III: Late Period, University of California Press, 1980. p. 91. ISBN 0-520-04020-1.

- "Gods of Ancient Egypt: Montu". www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

- Ruiz, Ana (2001). The Spirit of Ancient Egypt. Algora Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 9781892941688.

montu nomad.

- Pinch, Geraldine. Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-517024-5. p. 165.

- Pinch 2004, p. 166.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 203–4.

- Wilkinson 2003, p. 168.

- Wilkinson 2003, p. 150.

- Gae Callender: The Middle Kingdom Renaissance, In: Ian Shaw (ed): The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000, ISBN 0-19-815034-2, pp. 148-183.

- Hart 1986, p. 127.

- J.H. Breasted, Ancient Times: A History of the Early World; An Introduction to the Study of Ancient History and the Career of Early Man. Outlines of European History 1. Boston: Ginn and Company, 1914, p. 85.

- O'Connor, David; Cline, Eric H. (2001). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472088331.

- "Egyptian Accounts of the Battle of Kadesh". www.reshafim.org.il. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- Egyptian Accounts of the Battle of Kadesh

- Fletcher, Joann. (2011) Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend. HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-06-210605-6. pp. 114ss.

- Bard, Kathryn A. (2005-11-03). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 9781134665259.

- "The mammisi". www.reshafim.org.il. Archived from the original on 2018-04-15. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

Bibliography

- Hart, George (1986), A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-05909-7.

- Rachet, Guy (1994). Dizionario della civiltà egizia. Rome: Gremese Editore. ISBN 88-7605-818-4.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003), The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-05120-8.