Dmitri Mendeleev

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev (often romanized as Mendeleyev or Mendeleef) (English: /ˌmɛndəlˈeɪəf/ MEN-dəl-AY-əf;[2] Russian: Дмитрий Иванович Менделеев,[note 1] tr. Dmitriy Ivanovich Mendeleyev, IPA: [ˈdmʲitrʲɪj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ mʲɪnʲdʲɪˈlʲejɪf] (![]()

Dmitri Mendeleev | |

|---|---|

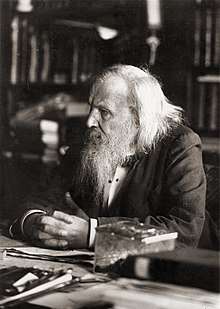

Mendeleev in 1897 | |

| Born | Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev 8 February 1834 Verkhnie Aremzyani, Tobolsk Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 2 February 1907 (aged 72) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg University |

| Known for | Formulating the periodic table of chemical elements |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry, physics |

| Academic advisors | Gustav Kirchhoff |

| Signature | |

| |

Early life

Mendeleev was born in the village of Verkhnie Aremzyani, near Tobolsk in Siberia, to Ivan Pavlovich Mendeleev (1783–1847) and Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleeva (née Kornilieva) (1793–1850).[3][4] Ivan worked as a school principal and a teacher of fine arts, politics and philosophy at the Tambov and Saratov gymnasiums.[5] Ivan's father, Pavel Maximovich Sokolov, was a Russian Orthodox priest from the Tver region.[6] As per the tradition of priests of that time, Pavel's children were given new family names while attending the theological seminary,[7] with Ivan getting the family name Mendeleev after the name of a local landlord.[8]

Maria Kornilieva came from a well-known family of Tobolsk merchants, founders of the first Siberian printing house who traced their ancestry to Yakov Korniliev, a 17th-century posad man turned a wealthy merchant.[9][10] In 1889, a local librarian published an article in the Tobolsk newspaper where he claimed that Yakov was a baptized Teleut, an ethnic minority known as "white Kalmyks" at the time.[11] Since no sources were provided and no documented facts of Yakov's life were ever revealed, biographers generally dismiss it as a myth.[12][13] In 1908, shortly after Mendeleev's death, one of his nieces published Family Chronicles. Memories about D. I. Mendeleev where she voiced "a family legend" about Maria's grandfather who married "a Kyrgyz or Tatar beauty whom he loved so much that when she died, he also died from grief".[14] This, however, contradicts the documented family chronicles, and neither of those legends is supported by Mendeleev's autobiography, his daughter's or his wife's memoirs.[4][15][16] Yet some Western scholars still refer to Mendeleev's supposed "Mongol", "Tatar", "Tartarian" or simply "Asian" ancestry as a fact.[17][18][19][20]

Mendeleev was raised as an Orthodox Christian, his mother encouraging him to "patiently search divine and scientific truth".[21] His son would later inform that he departed from the Church and embraced a form of "romanticized deism".[22]

Mendeleev was the youngest of 17 siblings, of whom "only 14 stayed alive to be baptized" according to Mendeleev's brother Pavel, meaning the others died soon after their birth.[5] The exact number of Mendeleev's siblings differs among sources and is still a matter of some historical dispute.[23][24] Unfortunately for the family's financial well-being, his father became blind and lost his teaching position. His mother was forced to work and she restarted her family's abandoned glass factory. At the age of 13, after the passing of his father and the destruction of his mother's factory by fire, Mendeleev attended the Gymnasium in Tobolsk.

In 1849, his mother took Mendeleev across Russia from Siberia to Moscow with the aim of getting Mendeleev enrolled at the Moscow University.[8] The university in Moscow did not accept him. The mother and son continued to Saint Petersburg to the father's alma mater. The now poor Mendeleev family relocated to Saint Petersburg, where he entered the Main Pedagogical Institute in 1850. After graduation, he contracted tuberculosis, causing him to move to the Crimean Peninsula on the northern coast of the Black Sea in 1855. While there, he became a science master of the 1st Simferopol Gymnasium. In 1857, he returned to Saint Petersburg with fully restored health.

Between 1859 and 1861, he worked on the capillarity of liquids and the workings of the spectroscope in Heidelberg. Later in 1861, he published a textbook named Organic Chemistry.[25] This won him the Demidov Prize of the Petersburg Academy of Sciences.[25]

On 4 April 1862, he became engaged to Feozva Nikitichna Leshcheva, and they married on 27 April 1862 at Nikolaev Engineering Institute's church in Saint Petersburg (where he taught).[26]

Mendeleev became a professor at the Saint Petersburg Technological Institute and Saint Petersburg State University in 1864,[25] and 1865, respectively. In 1865, he became Doctor of Science for his dissertation "On the Combinations of Water with Alcohol". He achieved tenure in 1867 at St. Petersburg University and started to teach inorganic chemistry, while succeeding Voskresenskii to this post;[25] by 1871, he had transformed Saint Petersburg into an internationally recognized center for chemistry research.

Periodic table

| Part of a series on the |

| Periodic table |

|---|

|

Periodic table forms |

|

By periodic table structure

|

|

|

By other characteristics

|

|

|

|

|

Data pages for elements

|

|

In 1863, there were 56 known elements with a new element being discovered at a rate of approximately one per year. Other scientists had previously identified periodicity of elements. John Newlands described a Law of Octaves, noting their periodicity according to relative atomic weight in 1864, publishing it in 1865. His proposal identified the potential for new elements such as germanium. The concept was criticized and his innovation was not recognized by the Society of Chemists until 1887. Another person to propose a periodic table was Lothar Meyer, who published a paper in 1864 describing 28 elements classified by their valence, but with no predictions of new elements.

After becoming a teacher in 1867, Mendeleev wrote the definitive textbook of his time: Principles of Chemistry (two volumes, 1868–1870). It was written as he was preparing a textbook for his course.[25] This is when he made his most important discovery.[25] As he attempted to classify the elements according to their chemical properties, he noticed patterns that led him to postulate his periodic table; he claimed to have envisioned the complete arrangement of the elements in a dream:[27][28][29][30][31]

I saw in a dream a table where all elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper, only in one place did a correction later seem necessary.

Unaware of the earlier work on periodic tables going on in the 1860s, he made the following table:

| Cl 35.5 | K 39 | Ca 40 |

| Br 80 | Rb 85 | Sr 88 |

| I 127 | Cs 133 | Ba 137 |

By adding additional elements following this pattern, Mendeleev developed his extended version of the periodic table.[34][35] On 6 March 1869, he made a formal presentation to the Russian Chemical Society, titled The Dependence between the Properties of the Atomic Weights of the Elements, which described elements according to both atomic weight (now called relative atomic mass) and valence.[36][37] This presentation stated that

- The elements, if arranged according to their atomic weight, exhibit an apparent periodicity of properties.

- Elements which are similar regarding their chemical properties either have similar atomic weights (e.g., Pt, Ir, Os) or have their atomic weights increasing regularly (e.g., K, Rb, Cs).

- The arrangement of the elements in groups of elements in the order of their atomic weights corresponds to their so-called valencies, as well as, to some extent, to their distinctive chemical properties; as is apparent among other series in that of Li, Be, B, C, N, O, and F.

- The elements which are the most widely diffused have small atomic weights.

- The magnitude of the atomic weight determines the character of the element, just as the magnitude of the molecule determines the character of a compound body.

- We must expect the discovery of many yet unknown elements – for example, two elements, analogous to aluminium and silicon, whose atomic weights would be between 65 and 75.

- The atomic weight of an element may sometimes be amended by a knowledge of those of its contiguous elements. Thus the atomic weight of tellurium must lie between 123 and 126, and cannot be 128. (Tellurium's atomic weight is 127.6, and Mendeleev was incorrect in his assumption that atomic weight must increase with position within a period.)

- Certain characteristic properties of elements can be foretold from their atomic weights.

Mendeleev published his periodic table of all known elements and predicted several new elements to complete the table in a Russian-language journal. Only a few months after, Meyer published a virtually identical table in a German-language journal.[38][39] Mendeleev has the distinction of accurately predicting the properties of what he called ekasilicon, ekaaluminium and ekaboron (germanium, gallium and scandium, respectively).[40][41]

Mendeleev also proposed changes in the properties of some known elements. Prior to his work, uranium was supposed to have valence 3 and atomic weight about 120. Mendeleev realized that these values did not fit in his periodic table, and doubled both to valence 6 and atomic weight 240 (close to the modern value of 238).[42]

For his predicted eight elements, he used the prefixes of eka, dvi, and tri (Sanskrit one, two, three) in their naming. Mendeleev questioned some of the currently accepted atomic weights (they could be measured only with a relatively low accuracy at that time), pointing out that they did not correspond to those suggested by his Periodic Law. He noted that tellurium has a higher atomic weight than iodine, but he placed them in the right order, incorrectly predicting that the accepted atomic weights at the time were at fault. He was puzzled about where to put the known lanthanides, and predicted the existence of another row to the table which were the actinides which were some of the heaviest in atomic weight. Some people dismissed Mendeleev for predicting that there would be more elements, but he was proven to be correct when Ga (gallium) and Ge (germanium) were found in 1875 and 1886 respectively, fitting perfectly into the two missing spaces.[43]

By using Sanskrit prefixes to name "missing" elements, Mendeleev may have recorded his debt to the Sanskrit grammarians of ancient India, who had created sophisticated theories of language based on their discovery of the two-dimensional patterns of speech sounds (arguably most strikingly exemplified by the Śivasūtras in Pāṇini's Sanskrit grammar). Mendeleev was a friend and colleague of the Sanskritist Otto von Böhtlingk, who was preparing the second edition of his book on Pāṇini[44] at about this time, and Mendeleev wished to honor Pāṇini with his nomenclature.[45][46][47]

The original draft made by Mendeleev would be found years later and published under the name Tentative System of Elements.[48]

Dmitri Mendeleev is often referred to as the Father of the Periodic Table. He called his table or matrix, "the Periodic System".[49]

Later life

In 1876, he became obsessed with Anna Ivanova Popova and began courting her; in 1881 he proposed to her and threatened suicide if she refused. His divorce from Leshcheva was finalized one month after he had married Popova (on 2 April[50]) in early 1882. Even after the divorce, Mendeleev was technically a bigamist; the Russian Orthodox Church required at least seven years before lawful remarriage. His divorce and the surrounding controversy contributed to his failure to be admitted to the Russian Academy of Sciences (despite his international fame by that time). His daughter from his second marriage, Lyubov, became the wife of the famous Russian poet Alexander Blok. His other children were son Vladimir (a sailor, he took part in the notable Eastern journey of Nicholas II) and daughter Olga, from his first marriage to Feozva, and son Ivan and twins from Anna.

Though Mendeleev was widely honored by scientific organizations all over Europe, including (in 1882) the Davy Medal from the Royal Society of London (which later also awarded him the Copley Medal in 1905),[51] he resigned from Saint Petersburg University on 17 August 1890. He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1892,[1] and in 1893 he was appointed director of the Bureau of Weights and Measures, a post which he occupied until his death.[52]

Mendeleev also investigated the composition of petroleum, and helped to found the first oil refinery in Russia. He recognized the importance of petroleum as a feedstock for petrochemicals. He is credited with a remark that burning petroleum as a fuel "would be akin to firing up a kitchen stove with bank notes".[53]

In 1905, Mendeleev was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The following year the Nobel Committee for Chemistry recommended to the Swedish Academy to award the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1906 to Mendeleev for his discovery of the periodic system. The Chemistry Section of the Swedish Academy supported this recommendation. The Academy was then supposed to approve the Committee's choice, as it has done in almost every case. Unexpectedly, at the full meeting of the Academy, a dissenting member of the Nobel Committee, Peter Klason, proposed the candidacy of Henri Moissan whom he favored. Svante Arrhenius, although not a member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, had a great deal of influence in the Academy and also pressed for the rejection of Mendeleev, arguing that the periodic system was too old to acknowledge its discovery in 1906. According to the contemporaries, Arrhenius was motivated by the grudge he held against Mendeleev for his critique of Arrhenius's dissociation theory. After heated arguments, the majority of the Academy chose Moissan by a margin of one vote.[54] The attempts to nominate Mendeleev in 1907 were again frustrated by the absolute opposition of Arrhenius.[55]

In 1907, Mendeleev died at the age of 72 in Saint Petersburg from influenza. His last words were to his physician: "Doctor, you have science, I have faith," which is possibly a Jules Verne quote.[56]

Other achievements

Mendeleev made other important contributions to chemistry. The Russian chemist and science historian Lev Chugaev characterized him as "a chemist of genius, first-class physicist, a fruitful researcher in the fields of hydrodynamics, meteorology, geology, certain branches of chemical technology (explosives, petroleum, and fuels, for example) and other disciplines adjacent to chemistry and physics, a thorough expert of chemical industry and industry in general, and an original thinker in the field of economy." Mendeleev was one of the founders, in 1869, of the Russian Chemical Society. He worked on the theory and practice of protectionist trade and on agriculture.

In an attempt at a chemical conception of the aether, he put forward a hypothesis that there existed two inert chemical elements of lesser atomic weight than hydrogen.[52] Of these two proposed elements, he thought the lighter to be an all-penetrating, all-pervasive gas, and the slightly heavier one to be a proposed element, coronium.

Mendeleev devoted much study and made important contributions to the determination of the nature of such indefinite compounds as solutions.

In another department of physical chemistry, he investigated the expansion of liquids with heat, and devised a formula similar to Gay-Lussac's law of the uniformity of the expansion of gases, while in 1861 he anticipated Thomas Andrews' conception of the critical temperature of gases by defining the absolute boiling-point of a substance as the temperature at which cohesion and heat of vaporization become equal to zero and the liquid changes to vapor, irrespective of the pressure and volume.[52]

Mendeleev is given credit for the introduction of the metric system to the Russian Empire.

He invented pyrocollodion, a kind of smokeless powder based on nitrocellulose. This work had been commissioned by the Russian Navy, which however did not adopt its use. In 1892 Mendeleev organized its manufacture.

Mendeleev studied petroleum origin and concluded hydrocarbons are abiogenic and form deep within the earth – see Abiogenic petroleum origin. He wrote: "The capital fact to note is that petroleum was born in the depths of the earth, and it is only there that we must seek its origin." (Dmitri Mendeleev, 1877)[57]

Intellectual activities beyond chemistry

Beginning in the 1870s, he published widely beyond chemistry, looking at aspects of Russian industry, and technical issues in agricultural productivity. He explored demographic issues, sponsored studies of the Arctic Sea, tried to measure the value of chemical fertilizers, and promoted the a merchant navy.[58] He was especially active in promoting the Russian petroleum industry, making careful detail comparisons with the more advanced industry in Pennsylvania.[59] He joined in the debate about the scientific claims of spiritualism, arguing that metaphysical idealism was no more than ignorant superstition. He bemoaned the widespread acceptance of spiritualism in Russian culture, and its negative effects on the study of science.[60] Although he was not well grounded in economic theory, he helped convince the Ministry of Finance in 1887-1891 to impose a temporary tariff in 1891 which, based on his wide travels in Europe, suggested it would allow Russian industry to mature faster.[61] After resigning his professorship at St. Petersburg University following a dispute with officials at the Ministry of Education in 1907, he became director of Russia's Central Bureau of Weights and Measures, he led the way to standardize fundamental prototypes and measurement procedures. He set up an inspection system, and introduced the metric system to Russia.[62][63]

Vodka myth

A very popular Russian story is that it was Mendeleev who came up with the 40% standard strength of vodka in 1894, after having been appointed Director of the Bureau of Weights and Measures with the assignment to formulate new state standards for the production of vodka. This story has, for instance, been used in marketing claims by the Russian Standard vodka brand that "In 1894, Dmitri Mendeleev, the greatest scientist in all Russia, received the decree to set the Imperial quality standard for Russian vodka and the 'Russian Standard' was born",[64] or that the vodka is "compliant with the highest quality of Russian vodka approved by the royal government commission headed by Mendeleev in 1894".[65]

While it is true that Mendeleev in 1892 became head of the Archive of Weights and Measures in Saint Petersburg, and evolved it into a government bureau the following year, that institution was never involved in setting any production quality standards, but was issued with standardising Russian trade weights and measuring instruments. Furthermore, the 40% standard strength was already introduced by the Russian government in 1843, when Mendeleev was nine years old.[65]

The basis for the whole story is a popular myth that Mendeleev's 1865 doctoral dissertation "A Discourse on the combination of alcohol and water" contained a statement that 38% is the ideal strength of vodka, and that this number was later rounded to 40% to simplify the calculation of alcohol tax. However, Mendeleev's dissertation was about alcohol concentrations over 70% and he never wrote anything about vodka.[65][66][67]

Commemoration

A number of places and objects are associated with the name and achievements of the scientist.

In Saint Petersburg his name was given to D. I. Mendeleev Institute for Metrology, the National Metrology Institute,[68] dealing with establishing and supporting national and worldwide standards for precise measurements. Next to it there is a monument to him that consists of his sitting statue and a depiction of his periodic table on the wall of the establishment.

In the Twelve Collegia building, now being the centre of Saint Petersburg State University and in Mendeleev's time – Head Pedagogical Institute – there is Dmitry Mendeleev's Memorial Museum Apartment[69] with his archives. The street in front of these is named after him as Mendeleevskaya liniya (Mendeleev Line).

In Moscow, there is the D. Mendeleyev University of Chemical Technology of Russia.[70]

After him was also named mendelevium, which is a synthetic chemical element with the symbol Md (formerly Mv) and the atomic number 101. It is a metallic radioactive transuranic element in the actinide series, usually synthesized by bombarding einsteinium with alpha particles.

The mineral mendeleevite-Ce, Cs6(Ce22Ca6)(Si70O175)(OH,F)14(H2O)21, was named in Mendeleev's honor in 2010.[71] The related species mendeleevite-Nd, Cs6[(Nd,REE)23Ca7](Si70O175)(OH,F)19(H2O)16, was described in 2015.[72]

A large lunar impact crater Mendeleev, that is located on the far side of the Moon, also bears the name of the scientist.

The Russian Academy of Sciences has occasionally awarded a Mendeleev Golden Medal since 1965.[73]

See also

Notes

- In Mendeleev's day, his name was written Дмитрій Ивановичъ Менделѣевъ.

References

- "Fellows of the Royal Society". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- "Mendeleev". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Rao, C N R; Rao, Indumati (2015). Lives and Times of Great Pioneers in Chemistry: (Lavoisier to Sanger). World Scientific. p. 119. ISBN 978-981-4689-07-6.

- Maria Mendeleeva (1951). D. I. Mendeleev's Archive: Autobiographical Writings. Collection of Documents. Volume 1 // Biographical notes about D. I. Mendeleev (written by me – D. Mendeleev), p. 13. – Leningrad: D. I. Mendeleev's Museum-Archive, 207 pages (in Russian)

- Maria Mendeleeva (1951). D. I. Mendeleev's Archive: Autobiographical Writings. Collection of Documents. Volume 1 // From a family tree documented in 1880 by brother Pavel Ivanovich, p. 11. Leningrad: D. I. Mendeleev's Museum-Archive, 207 pages (in Russian)

- Dmitriy Mendeleev: A Short CV, and A Story of Life, mendcomm.org

- Удомельские корни Дмитрия Ивановича Менделеева (1834–1907) Archived 8 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, starina.library.tver.ru

- Larcher, Alf (21 June 2019). "A mother's love: Maria Dmitrievna Mendeleeva". Chemistry in Australia magazine. Royal Australian Chemical Institute. ISSN 1839-2539. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- Yuri Mandrika (2004). Tobolsk Governorate Vedomosti: Staff and Authors. Anthology of Tobolsk Journalism of the late XIX – early XX centuries in 2 Books // From the interview with Maria Mendeleeva, born Kornilieva, p. 351. Tumen: Mandr i Ka, 624 pages

- Elena Konovalova (2006). A Book of the Tobolsk Governance. 1790–1917. Novosibirsk: State Public Scientific Technological Library, 528-page, p. 15 (in Russian) ISBN 5-94560-116-0

- Yuri Mandrika (2004). Tobolsk Governorate Vedomosti: Staff and Authors. Anthology of Tobolsk Journalism of the late XIX – early XX centuries in 2 Books // The Kornilievs, Tobolsk Manufacturers article by Stepan Mameev, p. 314. – Tumen: Mandr i Ka, 624 pages

- Eugenie Babaev (2009). "Mendelievia. Part 3" article from the Chemistry and Life – 21st Century journal at the MSU Faculty of Chemistry website (in Russian)

- Alexei Storonkin, Roman Dobrotyn (1984). D. I. Mendeleev's Life and Work Chronicles. Leningrad: Nauka, 539 pages, p. 25

- Nadezhda Gubkina (1908). Family Chronicles. Memories about D. I. Mendeleev. Saint Petersburg, 252 pages

- "Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev comes from indigenous Russian people", p. 5 // Olga Tritogova-Mendeleeva (1947). Mendeleev and His Family. Moscow: Academy of Sciences Publishing House, 104 pages

- Anna Mendeleeva (1928). Mendeleev in Life. Moscow: M. and S. Sabashnikov Publishing House, 194 pages

- Loren R. Graham, Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History, Cambridge University Press (1993), p. 45

- Isaac Asimov, Asimov on Chemistry, Anchoor Books (1975), p. 101

- Leslie Alan Horvitz, Eureka!: Scientific Breakthroughs that Changed the World, John Wiley & Sons (2002), p. 45

- Lennard Bickel, The deadly element: the story of uranium, Stein and Day (1979), p. 22

- Hiebert, Ray Eldon; Hiebert, Roselyn (1975). Atomic Pioneers: From ancient Greece to the 19th century. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Division of Technical Information. p. 25.

- Gordin, Michael D. (2004). A Well-ordered Thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev and the Shadow of the Periodic Table. Basic Books. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-465-02775-0.

Mendeleev seemed to have very few theological commitments. This was not for lack of exposure. His upbringing was actually heavily religious, and his mother – by far the dominating force in his youth – was exceptionally devout. One of his sisters even joined a fanatical religious sect for a time. Despite, or perhaps because of, this background, Mendeleev withheld comment on religious affairs for most of his life, reserving his few words for anti-clerical witticisms ... Mendeleev's son Ivan later vehemently denied claims that his father was devoutly Orthodox: "I have also heard the view of my father's 'church religiosity' – and I must reject this categorically. From his earliest years Father practically split from the church – and if he tolerated certain simple everyday rites, then only as an innocent national tradition, similar to Easter cakes, which he didn't consider worth fighting against." ... Mendeleev's opposition to traditional Orthodoxy was not due to either atheism or a scientific materialism. Rather, he held to a form of romanticized deism.

- Johnson, George (3 January 2006). "The Nitpicking of the Masses vs. the Authority of the Experts". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- When the Princeton historian of science Michael Gordin reviewed this article as part of an analysis of the accuracy of Wikipedia for the 14 December 2005 issue of Nature, he cited as one of Wikipedia's errors that "They say Mendeleev is the 14th child. He is the 14th surviving child of 17 total. 14 is right out." However in a January 2006 article in The New York Times, it was noted that in Gordin's own 2004 biography of Mendeleev, he also had the Russian chemist listed as the 17th child, and quoted Gordin's response to this as being: "That's curious. I believe that is a typographical error in my book. Mendeleyev was the final child, that is certain, and the number the reliable sources have is 13." Gordin's book specifically says that Mendeleev's mother bore her husband "seventeen children, of whom eight survived to young adulthood", with Mendeleev being the youngest. See: Johnson, George (3 January 2006). "The Nitpicking of the Masses vs. the Authority of the Experts". The New York Times. and Gordin, Michael (22 December 2005). "Supplementary information to accompany Nature news article "Internet encyclopaedias go head to head" (Nature 438, 900–901; 2005)" (PDF). Blogs.Nature.com. p. 178 – via 2004.

- Heilbron 2003, p. 509.

- "Семья Д.И.Менделеева". Rustest.spb.ru. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- John B. Arden (1998). "Science, Theology and Consciousness", Praeger Frederick A. p. 59: "The initial expression of the commonly used chemical periodic table was reportedly envisioned in a dream. In 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev claimed to have had a dream in which he envisioned a table in which all the chemical elements were arranged according to their atomic weight."

- John Kotz, Paul Treichel, Gabriela Weaver (2005). "Chemistry and Chemical Reactivity," Cengage Learning. p. 333

- Gerard I. Nierenberg (1986). "The art of creative thinking", Simon & Schuster, p. 201: Dmitri Mendeleev's solution for the arrangement of the elements that came to him in a dream.

- Helen Palmer (1998). "Inner Knowing: Consciousness, Creativity, Insight, and Intuition". J.P. Tarcher/Putnam. p. 113: "The sewing machine, for instance, invented by Elias Howe, was developed from material appearing in a dream, as was Dmitri Mendeleev's periodic table of elements"

- Simon S. Godfrey (2003). Dreams & Reality. Trafford Publishing. Chapter 2.: "The Russian chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev (1834–1907), described a dream in which he saw the periodic table of elements in its complete form." ISBN 1-4120-1143-4

- "The Soviet Review Translations" Summer 1967. Vol. VIII, No. 2, M.E. Sharpe, Incorporated, p. 38

- Myron E. Sharpe, (1967). "Soviet Psychology". Volume 5, p. 30.

- "A brief history of the development of the period table", wou.edu

- "Mendeleev and the Periodic Table" Archived 12 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, chemsheets.co.uk

- Seaborg, Glenn T (20 May 1994). "The Periodic Table: Tortuous path to man-made elements". Modern Alchemy: Selected Papers of Glenn T Seaborg. World Scientific. p. 179. ISBN 978-981-4502-99-3. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- Pfennig, Brian W. (3 March 2015). Principles of Inorganic Chemistry. Wiley. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-118-85902-5. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Nye, Mary Jo (2016). "Speaking in Tongues: Science's centuries-long hunt for a common language". Distillations. 2 (1): 40–43. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Gordin, Michael D. (2015). Scientific Babel: How Science Was Done Before and After Global English. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-00029-9.

- Marshall, James L. Marshall; Marshall, Virginia R. Marshall (2007). "Rediscovery of the elements: The Periodic Table" (PDF). The Hexagon: 23–29. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- Weeks, Mary Elvira (1956). The discovery of the elements (6th ed.). Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education.

- Scerri, Eric (2019). The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 9780190914363. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Emsley, John (2001). Nature's Building Blocks ((Hardcover, First Edition) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 521–522. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- Otto Böhtlingk, Panini's Grammatik: Herausgegeben, Ubersetzt, Erlautert und MIT Verschiedenen Indices Versehe. St. Petersburg, 1839–40.

- Kiparsky, Paul. "Economy and the construction of the Sivasutras". In M.M. Deshpande and S. Bhate (eds.), Paninian Studies. Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1991.

- Kak, Subhash (2004). "Mendeleev and the Periodic Table of Elements". Sandhan. 4 (2): 115–123. arXiv:physics/0411080. Bibcode:2004physics..11080K.

- "The Grammar of the Elements". American Scientist. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- "The Soviet Review Translations". Summer 1967. Vol. VIII, No. 2, M.E. Sharpe, Incorporated, p. 39

- Dmitri Mendeleev, Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- "Менделеев обвенчался за взятку". Gazeta.ua. 10 April 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Chisholm 1911.

-

- John W. Moore; Conrad L. Stanitski; Peter C. Jurs (2007). Chemistry: The Molecular Science, Volume 1. ISBN 978-0-495-11598-4. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- Gribbin, J (2002). The Scientists: A History of Science Told Through the Lives of Its Greatest Inventors. New York: Random House. p. 378. Bibcode:2003shst.book.....G. ISBN 978-0-8129-6788-3.

- Friedman, Robert M. (2001). The politics of excellence: behind the Nobel Prize in science. New York: Times Books. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-0-7167-3103-0.

- Last and Near-Last Words of the Famous, Infamous and Those In-Between By Joseph W. Lewis Jr. M.D.

- Mendeleev, D., 1877. L'Origine du pétrole. Revue Scientifique, 2e Ser., VIII, pp. 409–416.

- Alexander Vucinich, "Mendeleev's Views on science and society," ISIS 58:342-51.

- Francis Michael Stackenwalt, "Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev and the Emergence of the Modern Russian Petroleum Industry, 1863–1877." Ambix 45.2 (1998): 67-84.

- Don C. Rawson, "Mendeleev and the Scientific Claims of Spiritualism." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 122.1 (1978): 1-8.

- Vincent Barnett, "Catalysing Growth?: Mendeleev and the 1891 Tariff." in W. Samuels, ed., A Research Annual: Research in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology (2004) Vol. 22 Part 1 pp. 123-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-4154(03)22004-6 Online

- Nathan M. Brooks, "Mendeleev and metrology." Ambix 45.2 (1998): 116-128.

- Michael D. Gordin, "Measure of all the Russias: Metrology and governance in the Russian Empire." Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 4.4 (2003): 783-815.

- Sainsburys: Russian Standard Vodka 1L Linked 2014-06-28

- Evseev, Anton (21 November 2011). "Dmitry Mendeleev and 40 degrees of Russian vodka". Science. Moscow: English Pravda.ru. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- "Prominent Russians: Dmitry Mendeleev". Prominent Russians: Science and technology. Moscow: RT. 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Meija, Juris (2009). "Mendeleyev vodka challenge". Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 394 (1): 9–10. doi:10.1007/s00216-009-2710-3. PMID 19288087.

- ВНИИМ Дизайн Груп (13 April 2011). "D. I. Mendeleyev Institute for Metrology". Vniim.ru. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Saint-PetersburgState University. "Museum-Archives n.a. Dmitry Mendeleev – Museums – Culture and Sport – University – Saint-Petersburg state university". Eng.spbu.ru. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- "D. Mendeleyev University of Chemical Technology of Russia". Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- "Mendeleevite-Ce". Mindat.org. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Mendeleevite-Nd". Mindat.org. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Academy website

Further reading

- Gordin, Michael (2004). A Well-Ordered Thing: Dmitrii Mendeleev and the Shadow of the Periodic Table. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02775-0.

- Heilbron, John L. (2003). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974376-6.

- Mendeleev, Dmitry Ivanovich; Jensen, William B. (2005). Mendeleev on the Periodic Law: Selected Writings, 1869–1905. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-44571-7.

- Strathern, Paul (2001). Mendeleyev's Dream: The Quest For the Elements. New York: St Martins Press. ISBN 978-0-241-14065-9.

- Mendeleev, Dmitrii Ivanovich (1901). Principles of Chemistry. New York: Collier.

- "Mendeléeff, Dmitri IvanovichMITRI (1834–1907)". The Encyclopaedia Britannica; A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. XVIII (Medal to Mumps ) (11th ed.). Cambridge, England and New York: At the University Press. 1911. p. 115. Retrieved 5 October 2018 – via Internet Archive.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dmitri Mendeleev |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dmitri Mendeleev. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Dmitri Mendeleev |

- Works by Dmitri Mendeleev at Project Gutenberg

- Babaev, Eugene V. (February 2009). Dmitriy Mendeleev: A Short CV, and A Story of Life – 2009 biography on the occasion of Mendeleev's 175th anniversary

- Babaev, Eugene V., Moscow State University. Dmitriy Mendeleev Online

- Original Periodic Table, annotated.

- "Everything in its Place", essay by Oliver Sacks

- Works by or about Dmitri Mendeleev in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Dmitri Mendeleev's official site