Nationality

Nationality is a legal identification of a person in international law, establishing the person as a subject, a national, of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of the state against other states.[1]

| Legal status of persons |

|---|

| Concepts |

| Designations |

| Social politics |

| Conflict of laws and private international law |

|---|

| Preliminaries |

| Definitional elements |

| Connecting factors |

| Substantive legal areas |

| Enforcement |

Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that "Everyone has the right to a nationality," and "No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality." By international custom and conventions, it is the right of each state to determine who its nationals are.[2] Such determinations are part of nationality law. In some cases, determinations of nationality are also governed by public international law—for example, by treaties on statelessness and the European Convention on Nationality.

What the rights and duties of nationals are varies from state to state,[3] and is often complemented by citizenship law, in some contexts to the point where it is synonymous with nationality.[4] Nationality though differs technically and legally from citizenship, which is a different legal relationship between a person and a country. The noun national can include both citizens and non-citizens. The most common distinguishing feature of citizenship is that citizens have the right to participate in the political life of the state, such as by voting or standing for election. However, in most modern countries all nationals are citizens of the state, and full citizens are always nationals of the state.[5][6]

In older texts or other languages the word nationality, rather than ethnicity, is often used to refer to an ethnic group (a group of people who share a common ethnic identity, language, culture, lineage, history, and so forth). This older meaning of nationality is not defined by political borders or passport ownership and includes nations that lack an independent state (such as the Arameans, Scots, Welsh, English, Andalusians,[7] Basques, Catalans, Kurds, Kabyles, Baloch, Berbers, Bosniaks, Kashmiris, Palestinians, Sindhi, Tamils, Hmong, Inuit, Copts, Māori, Sikhs, Wakhi, Székelys, Xhosas and Zulus). Individuals may also be considered nationals of groups with autonomous status that have ceded some power to a larger sovereign state.

Nationality is also employed as a term for national identity, with some cases of identity politics and nationalism conflating the legal nationality as well as ethnicity with a national identity.

International law

Nationality is the status that allows a nation to grant rights to the subject and to impose obligations upon the subject.[6] In most cases, no rights or obligations are automatically attached to this status, although the status is a necessary precondition for any rights and obligations created by the state.[8]

In European law, nationality is the status or relationship that gives a nation the right to protect a person from other nations.[6] Diplomatic and consular protection are dependent upon this relationship between the person and the state.[6] A person's status as being the national of a country is used to resolve the conflict of laws.[8]

Within the broad limits imposed by few treaties and international law, states may freely define who are and are not their nationals.[6] However, since the Nottebohm case, other states are only required to respect claim by a state to protect an alleged national if the nationality is based on a true social bond.[6] In the case of dual nationality, states may determine the most effective nationality for a person, to determine which state's laws are most relevant.[8] There are also limits on removing a person's status as a national. Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that "Everyone has the right to a nationality," and "No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality."

National law

Nationals normally have the right to enter or return to the country they belong to. Passports are issued to nationals of a state, rather than only to citizens, because the passport is the travel document used to enter the country. However, nationals may not have the right of abode (the right to live permanently) in the countries that grant them passports.

Nationality versus citizenship

Conceptually, citizenship is focused on the internal political life of the state and nationality is a matter of international law.[9] Article 15 of the human rights states that everyone has the right to a nationality.[10] As such nationality in international law can be called and understood as citizenship,[10] or more generally as subject or belonging to a sovereign state, and not as ethnicity. This notwithstanding, around 10 million people are stateless.[10]

In the modern era, the concept of full citizenship encompasses not only active political rights, but full civil rights and social rights.[6] Nationality is a necessary but not sufficient condition to exercise full political rights within a state or other polity.[5] Nationality is required for full citizenship.

Historically, the most significant difference between a national and a citizen is that the citizen has the right to vote for elected officials, and to be elected.[6] This distinction between full citizenship and other, lesser relationships goes back to antiquity. Until the 19th and 20th centuries, it was typical for only a small percentage of people who belonged to a city or state to be full citizens. In the past, most people were excluded from citizenship on the basis of sex, socioeconomic class, ethnicity, religion, and other factors. However, they held a legal relationship with their government akin to the modern concept of nationality.[6]

United States nationality law defines some persons born in some U.S. outlying possessions as U.S. nationals but not citizens. British nationality law defines six classes of British national, among which "British citizen" is one class (having the right of abode in the United Kingdom, along with some "British subjects"). Similarly, in the Republic of China, commonly known as Taiwan, the status of national without household registration applies to people who have Republic of China nationality, but do not have an automatic entitlement to enter or reside in the Taiwan Area, and do not qualify for civic rights and duties there. Under the nationality laws of Mexico, Colombia, and some other Latin American countries, nationals do not become citizens until they turn 18. Israeli law distinguishes nationality from citizenship. The nationality of an Arab citizen of Israel is "Arab", not Israeli, while the nationality of a Jewish citizen is "Jewish" not Israeli.[11]

List of nationalities which do not have full citizenship rights

| Country | Form of nationality | Description |

|---|---|---|

| All forms of British nationalities except British Citizen | Among the 6 forms of British nationality, only British Citizens have the automatic right of abode in the United Kingdom, Isle of Man and Channel Islands, all the others don't have an automatic right to enter and live in the UK at all. Although the status of a British Overseas Territories citizen (BOTC) is derived from a connection of an overseas territory, it does not guarantee belonger status in that territory (which confers citizenship rights) as it is defined by the law of the territory itself which may be different from the British nationality law.[12] | |

| Non-citizens (Latvia) | This is the status conferred to people who were legal residents in Latvia upon restoring independence, but not eligible for Latvian citizenship, which are mainly ethnic Russians migrated during the Soviet occupation period. | |

| undefined citizenship | This is the term used to denote the legal residents in Estonia upon restoring independence who are not eligible for Estonian citizenship, similar to the Latvian non-citizens above. | |

| National without household registration | Rights in Taiwan are granted by both having the nationality and a household registration there. Without a household registration a person does not have automatic right to enter or live in Taiwan. These are mainly overseas ethnic Chinese who have right to the Republic of China nationality under the nationality law. | |

| Chinese nationals migrated to one of the SARs using one-way permit but before taking up permanent residence | These people, although technically Chinese nationals, are unable to vote or apply for a passport anywhere because rights in mainland China are associated with household registration which is relinquished upon migration, but rights in the SARs (e.g. right to vote and right to hold a passport) are given to permanent residents which is only eligible after 7 years of continuous residence. (They are eligible for applying Hong Kong Document of Identity for Visa Purposes or Macao Special Administrative Region Travel Permit as travel documents.) | |

| U.S. nationals who are not U.S. citizens | These people, mainly American Samoan, have the right to enter, work, and live in the United States as permanent residents but don't have the same voting rights as citizens and are barred from holding certain public offices which are restricted to citizens only. |

Nationality versus ethnicity

Nationality is sometimes used simply as an alternative word for ethnicity or national origin, just as some people assume that citizenship and nationality are identical.[13] In some countries, the cognate word for nationality in local language may be understood as a synonym of ethnicity or as an identifier of cultural and family-based self-determination, rather than on relations with a state or current government. For example, some Kurds say that they have Kurdish nationality, even though there is no Kurdish sovereign state at this time in history.

In the context of former Soviet Union and former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, "nationality" is often used as translation of the Russian nacional'nost' and Serbo-Croatian narodnost, which were the terms used in those countries for ethnic groups and local affiliations within the member states of the federation. In the Soviet Union, more than 100 such groups were formally recognized. Membership in these groups was identified on Soviet internal passports, and recorded in censuses in both the USSR and Yugoslavia. In the early years of the Soviet Union's existence, ethnicity was usually determined by the person's native language, and sometimes through religion or cultural factors, such as clothing.[14] Children born after the revolution were categorized according to their parents' recorded ethnicities. Many of these ethnic groups are still recognized by modern Russia and other countries.

Similarly, the term nationalities of China refers to ethnic and cultural groups in China. Spain is one nation, made up of nationalities, which are not politically recognized as nations (state), but can be considered smaller nations within the Spanish nation. Spanish law recognizes the autonomous communities of Andalusia, Aragon, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Catalonia, Valencia, Galicia and the Basque Country as "nationalities" (nacionalidades).

In 2013, the Supreme Court of Israel unanimously affirmed the position that "citizenship" (e.g. Israeli) is separate from le'om (Hebrew: לאום; "nationality" or "ethnic affiliation"; e.g. Jewish, Arab, Druze, Circassian), and that the existence of a unique "Israeli" le'om has not been proven. Israel recognizes more than 130 le'umim in total.[15][16][17]

Nationality versus national identity

National identity is a person's subjective sense of belonging to one state or to one nation. A person may be a national of a state, in the sense of being its citizen, without subjectively or emotionally feeling a part of that state, for example many migrants in Europe often identify with their ancestral and/or religious background rather than with the state of which they are citizens. Conversely, a person may feel that he belongs to one state without having any legal relationship to it. For example, children who were brought to the U.S. illegally when quite young and grow up there with little contact with their native country and its culture often have a national identity of feeling American, despite legally being nationals of a different country.

Dual nationality

Dual nationality is when a single person has a formal relationship with two separate, sovereign states.[18] This might occur, for example, if a person's parents are nationals of separate countries, and the mother's country claims all offspring of the mother's as their own nationals, but the father's country claims all offspring of the father's.

Nationality, with its historical origins in allegiance to a sovereign monarch, was seen originally as a permanent, inherent, unchangeable condition, and later, when a change of allegiance was permitted, as a strictly exclusive relationship, so that becoming a national of one state required rejecting the previous state.[18]

Dual nationality was considered a problem that caused conflict between states and sometimes imposed mutually exclusive requirements on affected people, such as simultaneously serving in two countries' military forces. Through the middle of the 20th century, many international agreements were focused on reducing the possibility of dual nationality. Since then, many accords recognizing and regulating dual nationality have been formed.[18]

Statelessness

Statelessness is the condition in which an individual has no formal or protective relationship with any state. This might occur, for example, if a person's parents are nationals of separate countries, and the mother's country rejects all offspring of mothers married to foreign fathers, but the father's country rejects all offspring born to foreign mothers. Although this person may have an emotional national identity, he or she may not legally be the national of any state.

Another stateless situation arises when a person holds a travel document (passport) which recognizes the bearer as having the nationality of a "state" which is not internationally recognized, has no entry in the International Organization for Standardization's country list, is not a member of the United Nations, etc. In the current era, persons native to Taiwan who hold Republic of China passports are one example.[19] [20]

Some countries ( like the Kuwait, UAE, Saudi Arabia) can also remove your citizenship; the reasons for removal are fraud and security issues. There are also people who are abandoned at birth and the parents whereabouts are not known.[21][22]

Conferment of nationality

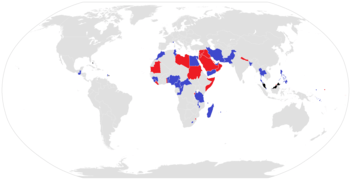

The following list includes states in which parents are able to confer nationality on their children or spouses.[23][24]

Africa

| Country: | Unmarried fathers able to confer nationality on children | Mothers able to confer nationality on children | Women able to confer nationality on spouses |

|---|---|---|---|

Americas

North America

| Nation: | Unmarried fathers able to confer nationality on children | Mothers able to confer nationality on children | Women able to confer nationality on spouses |

|---|---|---|---|

Caribbean

| Country: | Unmarried fathers able to confer nationality on children | Mothers able to confer nationality on children | Women able to confer nationality on spouses |

|---|---|---|---|

Central America

South America

Asia

| Country: | Unmarried fathers able to confer nationality on children | Mothers able to confer nationality on children | Women able to confer nationality on spouses |

|---|---|---|---|

Europe

| Country: | Unmarried fathers able to confer nationality on children | Mothers able to confer nationality on children | Women able to confer nationality on spouses |

|---|---|---|---|

Oceania

| Country: | Unmarried fathers able to confer nationality on children | Mothers able to confer nationality on children | Women able to confer nationality on spouses |

|---|---|---|---|

See also

- Blood quantum laws

- Demonym

- Imagined communities

- Intersectionality

- jus sanguinis

- jus soli

- List of adjectival and demonymic forms for countries and nations

- Nottebohm (Liechtenstein v. Guatemala), a 1955 case that is cited for its definitions of nationality

- Second-class citizen

- People

- Volk

Notes

- In Burundi, women nationals can confer their nationality on their children if their children are born out of wedlock to unknown fathers or their fathers disown them.

- Women only can confer their nationality on their children who are born in the nation; children born abroad can not acquire citizenship.

- Women nationals can confer their nationality on their children whose fathers are stateless, whose fathers' identities or nationalities are unknown, or whose fathers do not establish filiation with such children.

- In Madagascar, mothers can confer nationality on children born in wedlock if the father is stateless or of unknown nationality. Children born out of wedlock or to Madagascan mothers and foreign fathers can apply to the nationality until they reach majority.[25]

- Irrespective of gender, Canadian citizens (nationals) can sponsor their spouse, common-law partner, or conjugal partner, for permanent residency in Canada. Permanent residents then can apply for citizenship by naturalization after living in Canada for three years.[27]

- On 14 May 2019, the Iranian Islamic Consultative Assembly approved an amendment to their nationality law, in which women married to men with a foreign nationality should request to confer nationality on children under age 18, while children and spouses of Iranian men are granted nationality automatically. However, the Guardian Council should approve the amendment.[29] On 2 October 2019, the Guardian Council agreed to sign the bill into a law,[30] taking into account the background checks on foreign fathers.[31]

- In Iraq, nationality law limits the ability of Iraqi women to confer nationality on children who are born without the nation.

- In Kuwait, a person whose father is unknown or whose paternity has not been established may apply for Kuwaiti citizenship upon the age of majority.

- In Lebanon, women only can confer their citizenship on their children who are born out of wedlock and whose Lebanese mother recognizes them as her children during such children's minority.

- In Syria, mothers only can confer nationality on their children who are born in Syria and whose fathers do not establish filiation of such children.

- In United Arab Emirates, mothers only can confer nationality on their children who have lived in the UAE for at least six years.[32]

References

- Boll, Alfred Michael (2007). Multiple Nationality And International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 114. ISBN 90-04-14838-8.

- Convention on Certain Questions Relating to the Conflict of Nationality Laws Archived 2014-12-26 at the Wayback Machine. The Hague, 12 April 1930. Full text. Article 1, "It is for each State to determine under its own law who are its nationals...".

- Weis, Paul. Nationality and Statelessness in International Law. BRILL; 1979 [cited 19 August 2012]. ISBN 9789028603295. p. 29–61.

- Nationality and Statelessness: A Handbook for Parliamentarians (PDF). Handbook for Parliamentarians. UNHCR and IPU. 2005. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- Kadelbach, Stefan (2007). "Part V: Citizenship Rights in Europe". In Ehlers, Dirk (ed.). European Fundamental Rights and Freedoms. Berlin: De Gruyter Recht. pp. 547–548. ISBN 9783110971965.

- Boletín Oficial del Estado of Spain, n. 68 of 2007/03/20, p. 11872. Statute of Autonomy of Andalusia. Article 1: «Andalusia, as a historical nationality and in the exercise of the right of self-government recognized by the Constitution, is constituted in the Autonomous Community within the framework of the unity of the Spanish nation and in accordance with article 2 of the Constitution.»

- von Bogdandy, Armin; Bast, Jürgen, eds. (2009). Principles of European Constitutional Law (2nd ed.). Oxford: Hart Pub. pp. 449–451. ISBN 9781847315502.

- Sassen, Saskia (2002). "17. Towards Post-National and Denationalized Citzenship". In Isin, Engin F.; Turner, Bryan S. (eds.). Handbook of Citizenship Studies. SAGE Publications. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-7619-6858-0.

- "CITIZENSHIP & NATIONALITY". International Justice Resource Center (IJRC). Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- Richman, Sheldon. "To Be or Not to Be a Jewish State, That is the Question". Counter Punch.

- Kaur [2001] C-192/99, for a case in Bermuda

- Oommen, T. K. (1997). Citizenship, nationality, and ethnicity: reconciling competing identities. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7456-1620-9.

- Slezkine, Yuri (Summer 1994) "The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism" Slavic Review Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 414-452

- Cook, Jonathan. "Court nixes push for 'Israeli nationality'". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- "Is "Israeli" a Nationality?". Israel Democracy Institute. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- "Ornan v. Ministry of the Interior (CA 8573/08)" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- Turner, Bryan S; Isin, Engin F. Handbook of Citizenship Studies. SAGEs; 2003-01-29. ISBN 9780761968580. p. 278–279.

- US District Court, Washington, D.C., Roger C. S. Lin et al. v. USA, retrieved 2017-08-06,

Plaintiffs have essentially been persons without a state for almost 60 years.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 codes, retrieved 2017-08-06,

The Republic of China passport carried by native Taiwanese people clearly indicates the bearer's nationality as 'Republic of China.' Under international standards however, such a nationality designation does not exist. This is explained as follows. ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 codes are three-letter country codes defined in ISO 3166-1, part of the ISO 3166 standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), to represent countries, territories, etc. These three-letter abbreviations have been formally adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) as the official designation(s) of a 'recognized nationality' for use in manufacturing machine-readable passports, carried by travelers in order to deal with entry/exit procedures at customs authorities in all nations/territories of the world. According to these three-letter ISO country codes adopted by ICAO, the 'Republic of China' is not a recognized nationality in the international community, and thus there is no 'ROC' entry.

- Taylor, Adam (17 May 2016). "The controversial plan to give Kuwait's stateless people citizenship of a tiny, poor African island". Washington Post.

- Abrahamian, Atossa Araxia (November 11, 2015). "The bizarre scheme to transform a remote island into the new Dubai | Atossa Araxia Abrahamian" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Gender-Discriminatory Nationality Laws". Equal Nationality Rights. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- "Background Note on Gender Equality, Nationality Laws and Statelessness" (PDF). 8 March 2017.

- "Citizenship" (PDF). Pew Research Center. 5 August 2014.

- Citizenship Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. C-29, ¶¶3(1)(b), (g)–(h), §5.1.

- Immigration & Refugee Protection Act, S.C. 2001, c. 27, sub§12(1); Immigration & Refugee Protection Regulations, SOR/2002‑227, pt. 7, div. 1–2.

- Unites States Code, Title 8 (Aliens and Nationality), Chapter 12 (Immigration and Nationality), Part I (Nationality at Birth and Collective Naturalization), §1401 (Nationals and Citizens of United States at Birth)

- "Iran: Parliament OKs Nationality Law Reform". Human Rights Watch. 14 May 2019.

- "Victory for Iran's Women as Breakthrough Citizenship Law Is Passed". Bloomberg. 2 October 2019.

- "Iran women married to foreigners can pass citizenship to children". Al Jazeera. 2 October 2019.

- "'This will change our lives': Emirati mothers rejoice as children granted citizenship". The National. 28 May 2019.

Further reading

- White, Philip L. (2006). What is a nationality?, based on "Globalization and the Mythology of the Nation State," in A.G.Hopkins, ed. Global History: Interactions Between the Universal and the Local Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 257–284

- Grossman, Andrew. Gender and National Inclusion

- Lord Acton, Nationality (1862)