Kabyle people

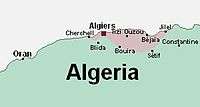

The Kabyle people (Kabyle: Iqbayliyen, iqβæjlijən) are a Berber people indigenous to Kabylia in the north of Algeria, spread across the Atlas Mountains, one hundred miles east of Algiers. They represent the largest Berber-speaking population of Algeria and the second largest in North Africa.

Iqbayliyen | |

|---|---|

Kabyle woman | |

| Total population | |

| c. ~5.5 million [1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Kabylie | |

| c. 3 to 3.5 million [1] | |

| c. ~+1 million [1] | |

| Languages | |

| Kabyle language Second languages: French, Arabic[2] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam, with minorities of Roman Catholicism and Protestantism | |

Many of the Kabyle have emigrated from Algeria, influenced by factors such as the Algerian Civil War,[3] cultural repression by the central Algerian government,[4] and overall industrial decline. Their diaspora has resulted in Kabyle people living in numerous countries. Large populations of Kabyle people settled in France and, to a lesser extent, Belgium, Canada and United States.

The Kabyle people speak Kabyle, a Berber language. Since the Berber Spring of 1980, they have been at the forefront of the fight for the official recognition of Berber languages in Algeria.

History

The Kabyle were relatively independent of outside control during the period of Ottoman Empire rule in North Africa. They lived primarily in three different kingdoms: the Kingdom of Kuku, the Kingdom of Ait Abbas, and the principality of Aït Jubar.[5] The area was gradually taken over by the French during their colonization beginning in 1857, despite vigorous resistance. Such leaders as Lalla Fatma n Soumer continued the resistance as late as Mokrani's rebellion in 1871.

French officials confiscated much land from the more recalcitrant tribes and granted it to colonists, who became known as pieds-noirs. During this period, the French carried out many arrests and deported resisters, mainly to New Caledonia (see: "Algerians of the Pacific"). Due to French colonization, many Kabyle emigrated into other areas inside and outside Algeria.[6] Over time, immigrant workers also went to France.

In the 1920s, Algerian immigrant workers in France organized the first party promoting independence. Messali Hadj, Imache Amar, Si Djilani, and Belkacem Radjef rapidly built a strong following throughout France and Algeria in the 1930s. They developed militants who became vital to the fighting for an independent Algeria. This became widespread after World War II.

Since Algeria gained independence in 1962, tensions have arisen between Kabylie and the central government on several occasions. In July 1962, the FLN (National Liberation Front) was split rather than united. Indeed, many actors who contributed to independence wanted a share of power but the ALN (National Liberation Army) directed by Houari Boumediene joined by Ahmed Ben Bella seemed to had the upper hand because they of their military forces.

In 1963 the FFS party of Hocine Aït Ahmed contested the authority of the FLN, which had promoted itself as the only party in the nation. Aït Ahmed and others consider that the central government led by Ben Bella is authoritarian and on September the 3rd 1963 the FFS (Socialist Forces front) was created by Hocine Aït Ahmed.[7] This party regrouped people against the regime in place and a few days after its proclamation, Ben Bella sent the army into Kabylie to repress the insurrection. Colonel Mohand Ouelhadj had also taken part in the FFS and in the maquis because he considered that the moujahidin were not treated as they should be.[8] At the beginning, the FFS wanted to negotiate with the government but since no agreement was reached, the maquis took up arms and its representatives swore not to give them up as long as democratic principles and justice were a part of the system. But after Mohand Ouelhadj’s defection, Aït Ahmed could barely sustain the movement and after the FLN congress on April 16, 1964 which reinforced the government’s legitimacy, he was arrested on October 1964. As a consequence, the insurrection was a failure in 1965 because it was hugely repressed by the forces of the ALN directed by Houari Boumediene. In 1965 Aït Ahmed was sentenced to death, but was later pardoned by Ben Bella. Approximately 400 deaths were counted amongst the maquis.[7]

In 1980, protesters mounted several months of demonstrations in Kabylie demanding the recognition of Berber as an official language; this period has been called the Berber Spring. In 1994–1995, the Kabyle conducted a school boycott, termed the "strike of the school bag". In June and July 1998, they protested, in events that turned violent, after the assassination of singer Matoub Lounes and passage of the law requiring use of Arabic in all fields.

In the months following April 2001 (called the Black Spring), major riots among the Kabyle took place following the killing of Masinissa Guermah, a young Kabyle, by gendarmes. At the same time, organized activism produced the Arouch, and neo-traditional local councils. The protests gradually decreased after the Kabyle won some concessions from President Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

On 6 January 2016, Tamazight was officially recognized in Algeria's constitution as a language that was equal to Arabic.[9]

Geography

The geography of the Kabyle region played an important role in the people's history. The difficult mountainous landscape of the Tizi Ouzou and Bejaia provinces served as a refuge, to which most of the Kabyle people retreated when under pressure or occupation. They were able to preserve their cultural heritage in such isolation from other cultural influences.

The area supported local dynasties (Numidia, Fatimids in the Kutama periods, Zirids, Hammadids, and Hafsids of Bejaïa) or Algerian modern nationalism, and the war of independence. The region was repeatedly occupied by various conquerors. Romans and Byzantines controlled the main road and valley during the period of antiquity and avoided the mountains (Mont ferratus).[10] During the spread of Islam, Arabs controlled plains but not all the countryside (they were called el aadua : enemy by the Kabyle).[11]

The Regency of Algiers, under Ottoman influence, tried to have indirect influence over the people (makhzen tribes of Amraoua, and marabout).[12]

The French gradually and totally conquered the region and set up a direct administration.

Algerian provinces with significant Kabyle-speaking populations include Tizi Ouzou, Béjaïa and Bouira, where they are a majority, as well as Boumerdes, Setif, Bordj Bou Arreridj, and Jijel. Algiers also has a significant Kabyle population, where they make up more than half of the capital's population.

The Kabyle region is referred to as Al Qabayel ("tribes") by the Arabic-speaking population and as Kabylie in French. Its indigenous inhabitants call it Tamurt Idurar ("Land of Mountains") or Tamurt n Iqbayliyen/Tamurt n Iqbayliyen ("Land of the Kabyle"). It is part of the Atlas Mountains and is located at the edge of the Mediterranean.

Culture and society

Language

The Kabyle ethnic group speak Kabyle, a Berber language of the Afro-Asiatic family. As second and third languages, many people speak Algerian Arabic, French and, to a lesser degree English.

During the first centuries of their history, Kabyles used the Tifinagh writing system. Since the beginning of the 19th century, and under French influence, Kabyle intellectuals began to use the Latin script. It is the basis for the modern Berber Latin alphabet.

After the independence of Algeria, some Kabyle activists tried to revive the old Tifinagh alphabet. This new version of Tifinagh has been called Neo-Tifinagh, but its use remains limited to logos. Kabyle literature has continued to be written in the Latin script.

Religion

The Kabyle people are mainly Muslim, with a small Christian minority.[13] Many Zawaya exist all over the region; the Rahmaniyya is the most prolific.

Catholics of Kabyle background generally live in France. Recently, the Protestant community has had significant growth, particularly among Evangelical denominations.[14]

Economy

The traditional economy of the area is based on arboriculture (orchards and olive trees) and on the craft industry (tapestry or pottery). Mountain and hill farming is gradually giving way to local industry (textile and agro-alimentary). In the middle of the 20th century, with the influence and funding by the Kabyle diaspora, many industries were developed in this region. It has become the second most important industrial region in the country after Algiers.

Politics

The Kabyle have been fierce activists in promoting the cause of Berber (Amazigh) identity. The movement has three groups: those Kabyle who identify as part of a larger Berber nation (Berberists); those who identify as part of the Algerian nation (known as "Algerianists", some view Algeria as an essentially Berber nation); and those who consider the Kabyle to be a distinct nation separate from (but akin to) other Berber peoples (known as Kabylists).

- Two political parties dominate in Kabylie and have their principal support base there: the Socialist Forces Front (FFS), led by Hocine Aït Ahmed, and the Rally for Culture and Democracy (RCD), led by Saïd Sadi. Both parties are secularist, Berberist and Algerianist.

- The Arouch emerged during the Black Spring of 2001 as a revival of the village assembly, a traditional Kabyle form of democratic organization. The Arouch share roughly the same political views as the FFS and the RCD.

- The MAK (Movement for the Autonomy of Kabylie) also emerged during the Black Spring, It claimed the right for a regional autonomy of Kabylie. On 21 April 2010, MAK proclaimed a Provisional Government of Kabylie in exile (ANAVAD). Ferhat Mehenni was elected President by the National Council of the MAK.[15] In 2013, MAK officially became an independantist movement and changed its name to The Mouvement for the Self-determination of Kabylie.

Diaspora

For historical and economic reasons, many Kabyles have emigrated to France, both for work and to escape political persecution. They now number around 1 million people.[16][17] Some notable French people are of full or partial Kabyle descent. Some tribes in the rif of Morocco such as the mtalssa or ibdarsen can trace their roots to kabylie.

Notable people

Sports

- Karim Benzema

- Nabil Ghilas

- Rabah Madjer

- Kylian Mbappé (through his mother)

- Samir Nasri

- Karim Ziani (through his father)

- Zinedine Zidane

Business

Entertainment

- Cinema

- Isabelle Adjani (through her father)

- Mhamed Arezki

- Dany Boon (through his father)

- Marion Cotillard (through her mother)

- Fellag

- Samy Naceri (through his father)

- Marie-José Nat (through her father)

- Daniel Prévost (through his father)

- Jacques Villeret (through his father)

- Malik Zidi (through his father)

- Music

- Idir

- Matoub Lounes

- Lounis Ait Menguellet

- Souad Massi

- Marcel Mouloudji (through his father)

- Sinik (through his father)

- DJ Snake (through his mother)

- Sofiane

- Soolking

- YL

Politics

- Jean-Baptiste Djebbari (through his paternal great-grand-father)

Writers

See also

- Berber people

- Kabylism and Berberism

- Kabyle language

- Famous Kabyles

Notes and references

- "Kabyles around the world". Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- Frawley, William J. (2003). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics: AAVE - Esperanto, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0195139778. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "The Kabyle Berbers, AQIM and the search for peace in Algeria | Algeria | al Jazeera".

- http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a585705.pdf

- E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 4, publié par M. Th. Houtsma, Page: 600

- Bélaïd Abane, L'Algérie en guerre: Abane Ramdane et les fusils de la rébellion, p. 74

- Monbeig, Pierre (1992). "Une opposition politique dans l'impasse. Le FFS de Hocine Aït-Ahmed". Revue du monde musulman et de la Méditerranée. 65 (1): 125–140. doi:10.3406/remmm.1992.1560. ISSN 0997-1327.

- Said Malik Cheurfa ⵣ (2011-08-03), Révolte de Hocine Ait Ahmed et Mohand Oulhadj en 28 septembre 1963 par Malik Cheurfa.flv, retrieved 2019-04-22

- "AVANT PROJET DE REVISION DE LA CONSTITUTION" (PDF). Algeria Press Service. 6 January 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "Ebook LA KABYLIE ORIENTALE DANS L'HISTOIRE - Pays des Kutuma et guerre coloniale de Hosni Kitouni". www.harmatheque.com. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- Abdelfettah Lalmi, Nedjma (2004-01-01). "Du mythe de l'isolat kabyle". Cahiers d'Études Africaines (in French). 44 (175): 507–531. doi:10.4000/etudesafricaines.4710. ISSN 0008-0055.

- Universalis, Encyclopædia. "KABYLES". Encyclopædia Universalis. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- Abdelmadjid Hannoum, Violent Modernity: France in Algeria, Page 124, 2010, Harvard Center for Middle Eastern studies, Cambridge, Massachusetts.Amar Boulifa, Le Djurdjura à travers l'histoire depuis l'Antiquité jusqu'en 1830 : organisation et indépendance des Zouaoua (Grande Kabylie), Page 197, 1925, Algiers.

- Lucien Oulahbib, Le monde arabe existe-t-il ?, page 12, 2005, Editions de Paris, Paris.

- www. kabylia-gov.org, Kabylia Government website

- Salem Chaker, "Pour une histoire sociale du berbère en France" Archived 2012-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, Les Actes du Colloque Paris - Inalco, Octobre 2004

- James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: D-K, Good Publishing Group, 2002, p.863. Quote: "Outside North Africa, the largest Kabyle community, numbering around 1 million, is in France."

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Kabyle people |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kabyle people. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Kabyles. |

- Provisional Government of Kabylie (ANAVAD)

- Kabyle Movement of Autonomy

- Kabyle centric news site (in Kabyle)

- Social web site

- Kabyle centric news site (in French)

- Ethnologue.com about Kabyle language

- Algerian linguistic policy (in French)

- Cultural site (in French)

- Analysis