Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh (Balochi: Mehrgaŕh; Urdu: مہرگڑھ) is a Neolithic site (dated c. 7000 BCE to c. 2500/2000 BCE), which lies on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan, Pakistan.[1] Mehrgarh is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River valley and between the present-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, Kalat and Sibi. The site was discovered in 1974 by an archaeological team directed by French archaeologists Jean-François Jarrige and Catherine Jarrige, and was excavated continuously between 1974 and 1986, and again from 1997 to 2000. Archaeological material has been found in six mounds, and about 32,000 artifacts have been collected. The earliest settlement at Mehrgarh—in the northeast corner of the 495-acre (2.00 km2) site—was a small farming village dated between 7000 BCE and 5500 BCE.

Urdu: مہرگڑھ | |

Ruins of houses at Mehrgarh | |

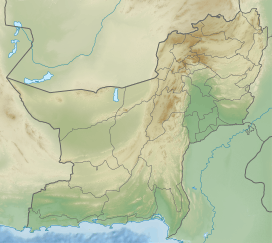

Shown within Balochistan, Pakistan  Mehrgarh (Pakistan) | |

| Alternative name | Mehrgahr, Merhgarh, Merhgahr |

|---|---|

| Location | Dhadar, Balochistan, Pakistan |

| Region | South Asia |

| Coordinates | 29°23′N 67°37′E |

| History | |

| Founded | Approximately 7000 BCE |

| Abandoned | Approximately 2600 BCE |

| Periods | Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1974–1986, 1997–2000 |

| Archaeologists | Jean-François Jarrige, Catherine Jarrige |

| Succeeded by: Indus Valley Civilization | |

History

Mehrgarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in South Asia.[2][3][note 1] Mehrgarh was influenced by the Near Eastern Neolithic,[13] with similarities between "domesticated wheat varieties, early phases of farming, pottery, other archaeological artefacts, some domesticated plants and herd animals."[14][note 2] According to Parpola, the culture migrated into the Indus Valley and became the Indus Valley Civilisation.[15]

Jean-Francois Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes "the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia,"[16][note 2] and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus valley, which are evidence of a "cultural continuum" between those sites. But given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background," and is not a "'backwater' of the Neolithic culture of the Near East."[16]

Lukacs and Hemphill suggest an initial local development of Mehrgarh, with a continuity in cultural development but a change in population. According to Lukacs and Hemphill, while there is a strong continuity between the neolithic and chalcolithic (Copper Age) cultures of Mehrgarh, dental evidence shows that the chalcolithic population did not descend from the neolithic population of Mehrgarh,[32] which "suggests moderate levels of gene flow."[32] They wrote that "the direct lineal descendents of the Neolithic inhabitants of Mehrgarh are to be found to the south and the east of Mehrgarh, in northwestern India and the western edge of the Deccan plateau," with neolithic Mehrgarh showing greater affinity with chalcolithic Inamgaon, south of Mehrgarh, than with chalcolithic Mehrgarh.[32][note 3]

Gallego Romero et al. (2011) state that their research on lactose tolerance in India suggests that "the west Eurasian genetic contribution identified by Reich et al. (2009) principally reflects gene flow from Iran and the Middle East."[35] Gallego Romero notes that Indians who are lactose-tolerant show a genetic pattern regarding this tolerance which is "characteristic of the common European mutation."[36] According to Romero, this suggests that "the most common lactose tolerance mutation made a two-way migration out of the Middle East less than 10,000 years ago. While the mutation spread across Europe, another explorer must have brought the mutation eastward to India – likely traveling along the coast of the Persian Gulf where other pockets of the same mutation have been found."[36] They further note that "[t]he earliest evidence of cattle herding in south Asia comes from the Indus River Valley site of Mehrgarh and is dated to 7,000 YBP."[35][note 4]

Periods of occupation

Archaeologists divide the occupation at the site into eight periods.

Mehrgarh Period I (7000 BCE-5500 BCE)

The Mehrgarh Period I (7000 BCE-5500 BCE) was Neolithic and aceramic, without the use of pottery. The earliest farming in the area was developed by semi-nomadic people using plants such as wheat and barley and animals such as sheep, goats and cattle. The settlement was established with simple mud buildings and most of them had four internal subdivisions. Numerous burials have been found, many with elaborate goods such as baskets, stone and bone tools, beads, bangles, pendants and occasionally animal sacrifices, with more goods left with burials of males. Ornaments of sea shell, limestone, turquoise, lapis lazuli and sandstone have been found, along with simple figurines of women and animals. Sea shells from far sea shore and lapis lazuli found as far away as present-day Badakshan, Afghanistan shows good contact with those areas. A single ground stone axe was discovered in a burial, and several more were obtained from the surface. These ground stone axes are the earliest to come from a stratified context in South Asia. Periods I, II and III are contemporaneous with another site called Kili Gul Mohammad

The aceramic Neolithic phase in the region is now called 'Kili Gul Muhammad phase', and it is dated 7000-5000 BC. Yet the Kili Gul Muhammad site, itself, may have started c. 5500 BC.[38]

In 2001, archaeologists studying the remains of two men from Mehrgarh made the discovery that the people of this civilization had knowledge of proto-dentistry. In April 2006, it was announced in the scientific journal Nature that the oldest (and first early Neolithic) evidence for the drilling of human teeth in vivo (i.e. in a living person) was found in Mehrgarh. According to the authors, their discoveries point to a tradition of proto-dentistry in the early farming cultures of that region. "Here we describe eleven drilled molar crowns from nine adults discovered in a Neolithic graveyard in Pakistan that dates from 7,500 to 9,000 years ago. These findings provide evidence for a long tradition of a type of proto-dentistry in an early farming culture."[39]

Mehrgarh Period II (5500 BCE–4800 BCE) and Period III (4800 BCE–3500 BCE)

The Mehrgarh Period II (5500 BCE–4800 BCE) and Merhgarh Period III (4800 BCE–3500 BCE) were ceramic Neolithic, using pottery, and later chalcolithic. Period II is at site MR4 and Period III is at MR2.[40] Much evidence of manufacturing activity has been found and more advanced techniques were used. Glazed faience beads were produced and terracotta figurines became more detailed. Figurines of females were decorated with paint and had diverse hairstyles and ornaments. Two flexed burials were found in Period II with a red ochre cover on the body. The amount of burial goods decreased over time, becoming limited to ornaments and with more goods left with burials of females. The first button seals were produced from terracotta and bone and had geometric designs. Technologies included stone and copper drills, updraft kilns, large pit kilns and copper melting crucibles. There is further evidence of long-distance trade in Period II: important as an indication of this is the discovery of several beads of lapis lazuli, once again from Badakshan. Mehrgarh Periods II and III are also contemporaneous with an expansion of the settled populations of the borderlands at the western edge of South Asia, including the establishment of settlements like Rana Ghundai, Sheri Khan Tarakai, Sarai Kala, Jalilpur and Ghaligai.[40]

Mehrgarh Periods IV, V and VI (3500 BCE-3000 BCE)

Period IV was 3500 to 3250 BCE. Period V from 3250 to 3000 BCE and period VI was around 3000 BCE.[42] The site containing Periods IV to VII is designated as MR1.[40]

Mehrgarh Period VII (2600 BCE-2000 BCE)

Somewhere between 2600 BCE and 2000 BCE, the city seems to have been largely abandoned in favor of the larger and fortified town Nausharo five miles away when the Indus Valley Civilization was in its middle stages of development. Historian Michael Wood suggests this took place around 2500 BCE.[43]

Mehrgarh Period VIII

The last period is found at the Sibri cemetery, about 8 kilometers from Mehrgarh.[40]

Lifestyle and technology

Early Mehrgarh residents lived in mud brick houses, stored their grain in granaries, fashioned tools with local copper ore, and lined their large basket containers with bitumen. They cultivated six-row barley, einkorn and emmer wheat, jujubes and dates, and herded sheep, goats and cattle. Residents of the later period (5500 BCE to 2600 BCE) put much effort into crafts, including flint knapping, tanning, bead production, and metal working.[44] Mehrgarh is probably the earliest known center of agriculture in South Asia.[45]

The oldest known example of the lost-wax technique comes from a 6,000-year-old wheel-shaped copper amulet found at Mehrgarh. The amulet was made from unalloyed copper, an unusual innovation that was later abandoned.[46]

Artifacts

_Mehrgarh_style.jpg)

Human figurines

The oldest ceramic figurines in South Asia were found at Mehrgarh. They occur in all phases of the settlement and were prevalent even before pottery appears. The earliest figurines are quite simple and do not show intricate features. However, they grow in sophistication with time and by 4000 BC begin to show their characteristic hairstyles and typical prominent breasts. All the figurines up to this period were female. Male figurines appear only from period VII and gradually become more numerous. Many of the female figurines are holding babies, and were interpreted as depictions of the "mother goddess". However, due to some difficulties in conclusively identifying these figurines with the "mother goddess", some scholars prefer using the term "female figurines with likely cultic significance".[48][49][50]

Pottery

Evidence of pottery begins from Period II. In period III, the finds become much more abundant as the potter's wheel is introduced, and they show more intricate designs and also animal motifs.[40] The characteristic female figurines appear beginning in Period IV and the finds show more intricate designs and sophistication. Pipal leaf designs are used in decoration from Period VI.[52] Some sophisticated firing techniques were used from Period VI and VII and an area reserved for the pottery industry has been found at mound MR1. However, by Period VIII, the quality and intricacy of designs seem to have suffered due to mass production, and due to a growing interest in bronze and copper vessels.[42]

Burials

There are two types of burials in the Mehrgarh site. There were individual burials where a single individual was enclosed in narrow mud walls and collective burials with thin mud brick walls within which skeletons of six different individuals were discovered. The bodies in the collective burials were kept in a flexed position and were laid east to west. Child bones were found in large jars or urn burials (4000~3300 BCE).[53]

See also

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Pakistan |

|

| Timeline |

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

Medieval

|

|

Early modern

|

|

Modern

|

|

History of provinces |

|

| Outline of South Asian history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Palaeolithic (2,500,000–250,000 BC) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Neolithic (10,800–3300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chalcolithic (3500–1500 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bronze Age (3300–1300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iron Age (1500–200 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Middle Kingdoms (230 BC – AD 1206) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late medieval period (1206–1526)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern period (1526–1858)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial states (1510–1961)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Periods of Sri Lanka

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Specialised histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Indus Valley Civilization and the list of Indus Valley Civilization sites

- List of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilization

- Hydraulic engineering of the Indus Valley Civilization

- Bhirrana

- Mundigak — archaeological site in Kandahar Province

- Hadda — archaeological site in Nangarhar Province

- Surkh Kotal — archaeological site in Baghlan Province

- Mes Aynak — archaeological site in Logar Province

- Sheri Khan Tarakai — archaeological site in Bannu

- Mohenjo-daro — archaeological site in Sindh

- Harappa — archaeological site in Punjab

- Bolan Pass

- Nausharo

- Pirak

- Chanhudaro

- Quetta

- List of Stone Age art

Notes

- Excavations at Bhirrana, Haryana, in India between 2006 and 2009, by archaeologist K. N. Dikshit, provided six artefacts, including "relatively advanced pottery," so-called Hakra ware, which were dated at a time bracket between 7380 and 6201 BCE.[4][5][6][7] These dates compete with Mehrgarh for being the oldest site for cultural remains in the area.[8]

Yet, Dikshit and Mani clarify that this time-bracket concerns only charcoal samples, which were radio-carbon dated at respectively 7570–7180 BCE (sample 2481) and 6689–6201 BCE (sample 2333).[9][10] Dikshit further writes that the earliest phase concerns 14 shallow dwelling-pits which "could accommodate about 3–4 people."[11] According to Dikshit, in the lowest level of these pits wheel-made Hakra Ware was found which was "not well finished,"[11] together with other wares.[12] - According to Gangal et al. (2014), there is strong archeological and geographical evidence that neolithic farming spread from the Near East into north-west India.[13][17] Gangal et al. (2014):[13] "There are several lines of evidence that support the idea of connection between the Neolithic in the Near East and in the Indian subcontinent. The prehistoric site of Mehrgarh in Baluchistan (modern Pakistan) is the earliest Neolithic site in the north-west Indian subcontinent, dated as early as 8500 BCE.[18][18]

Neolithic domesticated crops in Mehrgarh include more than 90% barley and a small amount of wheat. There is good evidence for the local domestication of barley and the zebu cattle at Mehrgarh [19],[19] [20],[20] but the wheat varieties are suggested to be of Near-Eastern origin, as the modern distribution of wild varieties of wheat is limited to Northern Levant and Southern Turkey [21].[21] A detailed satellite map study of a few archaeological sites in the Baluchistan and Khybar Pakhtunkhwa regions also suggests similarities in early phases of farming with sites in Western Asia [22].[22] Pottery prepared by sequential slab construction, circular fire pits filled with burnt pebbles, and large granaries are common to both Mehrgarh and many Mesopotamian sites [23].[23] The postures of the skeletal remains in graves at Mehrgarh bear strong resemblance to those at Ali Kosh in the Zagros Mountains of southern Iran [19].[19] Clay figurines found in Mehrgarh resemble those discovered at Teppe Zagheh on the Qazvin plain south of the Elburz range in Iran (the 7th millennium BCE) and Jeitun in Turkmenistan (the 6th millennium BCE) [24].[24] Strong arguments have been made for the Near-Eastern origin of some domesticated plants and herd animals at Jeitun in Turkmenistan (pp. 225–227 in [25]).[25]

The Near East is separated from the Indus Valley by the arid plateaus, ridges and deserts of Iran and Afghanistan, where rainfall agriculture is possible only in the foothills and cul-de-sac valleys [26].[26] Nevertheless, this area was not an insurmountable obstacle for the dispersal of the Neolithic. The route south of the Caspian sea is a part of the Silk Road, some sections of which were in use from at least 3,000 BCE, connecting Badakhshan (north-eastern Afghanistan and south-eastern Tajikistan) with Western Asia, Egypt and India [27].[27] Similarly, the section from Badakhshan to the Mesopotamian plains (the Great Khorasan Road) was apparently functioning by 4,000 BCE and numerous prehistoric sites are located along it, whose assemblages are dominated by the Cheshmeh-Ali (Tehran Plain) ceramic technology, forms and designs [26].[26] Striking similarities in figurines and pottery styles, and mud-brick shapes, between widely separated early Neolithic sites in the Zagros Mountains of north-western Iran (Jarmo and Sarab), the Deh Luran Plain in southwestern Iran (Tappeh Ali Kosh and Chogha Sefid), Susiana (Chogha Bonut and Chogha Mish), the Iranian Central Plateau (Tappeh-Sang-e Chakhmaq), and Turkmenistan (Jeitun) suggest a common incipient culture [28].[28] The Neolithic dispersal across South Asia plausibly involved migration of the population ([29][29] and [25], pp. 231–233).[25] This possibility is also supported by Y-chromosome and mtDNA analyses [30],[30] [31]."[31] - Genetic research shows a complex pattern of human migrations.[17] Kivisild et al. (1999) note that "a small fraction of the West Eurasian mtDNA lineages found in Indian populations can be ascribed to a relatively recent admixture."[33] at ca. 9,300 ± 3,000 years before present,[34] which coincides with "the arrival to India of cereals domesticated in the Fertile Crescent" and "lends credence to the suggested linguistic connection between the Elamite and Dravidic populations."[34] Singh et al. (2016) investigated the distribution of J2a-M410 and J2b-M102 in South Asia, which "suggested a complex scenario that cannot be explained by a single wave of agricultural expansion from Near East to South Asia,"[17] but also note that "regardless of the complexity of dispersal, NW region appears to be the corridor for entry of these haplogroups into India."[17]

- Gallego romero et al. (2011) refer to (Meadow 1993):[35] Meadow RH. 1993. Animal domestication in the Middle East: a revised view from the eastern margin. In: Possehl G, editor. Harappan civilization. New Delhi (India): Oxford University Press and India Book House. p 295–320.[37]

References

- "Stone age man used dentist drill".

- "Archeologists confirm Indian civilization is 2000 years older than previously believed, Jason Overdorf, Globalpost, 28 November 2012".

- "Indus Valley 2,000 years older than thought". 4 November 2012.

- "Archeologists confirm Indian civilization is 8000 years old, Jhimli Mukherjee Pandey, Times of India, 29 May 2016".

- "History What their lives reveal". 4 January 2013.

- "Haryana's Bhirrana oldest Harappan site, Rakhigarhi Asia's largest: ASI". The Times of India. 15 April 2015.

- Dikshit 2013, p. 132, 131.

- Mani 2008, p. 237.

- Dikshit 2013, p. 129.

- Dikshit 2013, p. 130.

- Gangal 2014.

- Singh 2016, p. 5.

- Parpola 2015, p. 17.

- Jean-Francois Jarrige Mehrgarh Neolithic Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Paper presented in the International Seminar on the "First Farmers in Global Perspective," Lucknow, India, 18–20 January 2006

- Singh 2016.

- Possehl GL (1999) Indus Age: The Beginnings. Philadelphia: Univ. Pennsylvania Press.

- Jarrige JF (2008) Mehrgarh Neolithic. Pragdhara 18: 136–154

- Costantini L (2008) The first farmers in Western Pakistan: the evidence of the Neolithic agropastoral settlement of Mehrgarh. Pragdhara 18: 167–178

- Fuller DQ (2006) Agricultural origins and frontiers in South Asia: a working synthesis. J World Prehistory 20: 1–86

- Petrie, CA; Thomas, KD (2012). "The topographic and environmental context of the earliest village sites in western South Asia". Antiquity. 86 (334): 1055–1067. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00048249.

- Goring-Morris, AN; Belfer-Cohen, A (2011). "Neolithization processes in the Levant: the outer envelope". Curr Anthropol. 52: S195–S208. doi:10.1086/658860.

- Jarrige C (2008) The figurines of the first farmers at Mehrgarh and their offshoots. Pragdhara 18: 155–166

- Harris DR (2010) Origins of Agriculture in Western Central Asia: An Environmental-Archaeological Study. Philadelphia: Univ. Pennsylvania Press.

- Hiebert FT, Dyson RH (2002) Prehistoric Nishapur and frontier between Central Asia and Iran. Iranica Antiqua XXXVII: 113–149

- Kuzmina EE, Mair VH (2008) The Prehistory of the Silk Road. Philadelphia: Univ. Pennsylvania Press

- Alizadeh A (2003) Excavations at the prehistoric mound of Chogha Bonut, Khuzestan, Iran. Technical report, University of Chicago, Illinois.

- Dolukhanov P (1994) Environment and Ethnicity in the Ancient Middle East. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Quintana-Murci, L; Krausz, C; Zerjal, T; Sayar, SH; Hammer, MF; et al. (2001). "Y-chromosome lineages trace diffusion of people and languages in Southwestern Asia". Am J Hum Genet. 68 (2): 537–542. doi:10.1086/318200. PMC 1235289. PMID 11133362.

- Quintana-Murci, L; Chaix, R; Spencer Wells, R; Behar, DM; Sayar, H; et al. (2004). "Where West meets East: the complex mtDNA landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian corridor". Am J Hum Genet. 74 (5): 827–845. doi:10.1086/383236. PMC 1181978. PMID 15077202.

- Coningham & Young 2015, p. 114.

- Kivisild 1999, p. 1331.

- Kivisild 1999, p. 1333.

- Gallego Romero 2011, p. 9.

- Rob Mitchum (2011), Lactose Tolerance in the Indian Dairyland, ScienceLife

- Gallego Romero 2011, p. 12.

- Mukhtar Ahmed, Ancient Pakistan - An Archaeological History. Volume II: A Prelude to Civilization. Amazon, 2014 ISBN 1495941302 p387

- Coppa, A. et al. 2006. "Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry: Flint tips were surprisingly effective for drilling tooth enamel in a prehistoric population." Nature. Volume 440. 6 April 2006.

- Sharif, M; Thapar, B. K. (1999). "Food-producing Communities in Pakistan and Northern India". In Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson (ed.). History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 128–137. ISBN 978-81-208-1407-3. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Figure féminine - Les Musées Barbier-Mueller". www.musee-barbier-mueller.org.

- Maisels, Charles Keith. Early Civilizations of the Old World. Routledge. pp. 190–193.

- Wood, Michael (2005). In Search of the First Civilizations. BBC Books. p. 257. ISBN 978-0563522669. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Possehl, Gregory L. 1996. "Mehrgarh." Oxford Companion to Archaeology, edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press

- Meadow, Richard H. (1996). David R. Harris (ed.). The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. Psychology Press. pp. 393–. ISBN 978-1-85728-538-3. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- Thoury, M.; et al. (2016). "High spatial dynamics-photoluminescence imaging reveals the metallurgy of the earliest lost-wax cast object". Nature Communications. 7: 13356. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713356T. doi:10.1038/ncomms13356. PMC 5116070. PMID 27843139.

- "MET". www.metmuseum.org.

- Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. pp. 130–. ISBN 9788131711200. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- Sarah M. Nelson (February 2007). Worlds of gender: the archaeology of women's lives around the globe. Rowman Altamira. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-7591-1084-7. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- Sharif, M; Thapar, B. K. (January 1999). "Food-producing Communities in Pakistan and Northern India". History of civilizations of Central Asia. pp. 254–256. ISBN 9788120814073. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- Upinder Singh (1 September 2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Dibyopama, Astha; et al. (2015). "Human Skeletal Remains from Ancient Burial Sites in India: With Special Reference to Harappan Civilization". Korean J Phys Anthropol. 28 (1): 1–9. doi:10.11637/kjpa.2015.28.1.1.

Sources

- Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015), The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE, Cambridge University Press

- Gangal, Kavita; Sarson, Graeme R.; Shukurov, Anvar (2014), "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia", PLOS ONE, 9 (5): e95714, Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714, PMC 4012948, PMID 24806472

- Kivisild; et al. (1999), "Deep common ancestry of Indian and western-Eurasian mitochondrial DNA lineages" (PDF), Curr. Biol., 9 (22): 1331–1334, doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80057-3, PMID 10574762, archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2005

- Singh, Sakshi (2016), "Dissecting the influence of Neolithic demic diffusion on Indian Y-chromosome pool through J2-M172 haplogroup", Sci. Rep., 6: 19157, Bibcode:2016NatSR...619157S, doi:10.1038/srep19157, PMC 4709632, PMID 26754573

Further reading

- Mehrgarh

- Jarrige, J. F. (1979). "Excavations at Mehrgarh-Pakistan". In Johanna Engelberta Lohuizen-De Leeuw (ed.). South Asian archaeology 1975: papers from the third International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, held in Paris. Brill. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-90-04-05996-2. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Jarrige, Jean-Franois, Mehrgarh Neolithic

- Jarrige, C, J. F. Jarrige, R. H. Meadow, G. Quivron, eds (1995/6), Mehrgarh Field Reports 1974-85: From Neolithic times to the Indus Civilization.

- Jarrige J. F., Lechevallier M., Les fouilles de Mehrgarh, Pakistan : problèmes chronologiques [Excavations at Mehrgarh, Pakistan: chronological problems] (French).

- Lechevallier M., L'Industrie lithique de Mehrgarh (Pakistan) [The Lithic industry of Mehrgarh (Pakistan)] (French)

- Niharranjan Ray; Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (1 January 2000). "Pre-Harappan Neolithic-Chalcolothic Settlement at Mehrgarh, Baluchistan Pakistan". A sourcebook of Indian civilization. Orient Blackswan. pp. 560–. ISBN 978-81-250-1871-1. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Santoni, Marielle, Sibri and the South Cemetery of Mehrgarh: Third Millennium Connections between the Northern Kachi Plain (Pakistan) and Central Asia

- Lukacs, J. R., Dental Morphology and Odontometrics of Early Agriculturalists from Neolithic Mehrgarh, Pakistan

- Barthelemy De Saizieu B., Le Cimetière néolithique de Mehrgarh (Balouchistan pakistanais) : apport de l'analyse factorielle [The Neolithic cemetery of Mehrgarh (Balochistan Pakistan): Contribution of a factor analysis] (French).

- Indus Valley Civilization

- Gregory L. Possehl (2002). The Indus civilization: a contemporary perspective. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Jane McIntosh (2008). The ancient Indus Valley: new perspectives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan M.; Miller, Heather M. L. (1999). "Metal Technologies of the Indus Valley Tradition in Pakistan and Western India". In Vincent C. Pigott (ed.). The archaeometallurgy of the Asian old world. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-0-924171-34-5. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- South Asia

- Bridget Allchin; Frank Raymond Allchin (1982). The rise of civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28550-6. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Kenoyer, J. Mark (2005). Kimberly Heuston (ed.). The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford University Press. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-0-19-517422-9. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- Sinopoli, Carla M. (February 2007). "Gender and Archaeology in South and Southwest Asia". In Sarah M. Nelson (ed.). Worlds of gender: the archaeology of women's lives around the globe. Rowman Altamira. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-0-7591-1084-7. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (2002). Peter N. Peregrine, Melvin Ember (ed.). Encyclopedia of Prehistory: South and Southwest Asia. Springer. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-0-306-46262-7. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- South Asia paleoanthropology

- Kenneth A. R. Kennedy (2000). God-apes and fossil men: paleoanthropology of South Asia. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11013-1. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Michael D. Petraglia; Bridget Allchin (2007). The evolution and history of human populations in South Asia: inter-disciplinary studies in archaeology, biological anthropology, linguistics and genetics. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-5561-4. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Central Asia

- J. G. Shaffer; B. K. Thapar; et al. (2005). History of civilizations of Central Asia. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-102719-2. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Global history

- Steven Mithen (30 April 2006). After the ice: a global human history, 20,000-5000 BC. Harvard University Press. pp. 408–. ISBN 978-0-674-01999-7. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- India

- Avari, Burjor, India: The Ancient Past: A history of the Indian sub-continent from c. 7000 BC to AD 1200, Routledge.

- Singh, Upinder, A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th century, Dorling Kindersley, 2008, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Lallanji Gopal, V. C. Srivastava, History of Agriculture in India, up to c. 1200 AD.

- Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A history of India. Routledge. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Burton Stein (4 March 2015). "Ancient Days: The Pre-Formation of Indian Civilization". In David Arnold (ed.). A History of India. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6.

- Indo-Aryans

- Jim G. Shaffer; Diane A Lichtenstein (1995). George Erdösy (ed.). The Indo-Aryans of ancient South Asia: Language, material culture and ethnicity. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-3-11-014447-5. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mehrgarh. |

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.