Ali Kosh

Ali Kosh is a small Tell of the Early Neolithic period located in Ilam Province in west Iran, in the Zagros Mountains.[1] It was excavated by Frank Hole and Kent Flannery in the 1960s.[2]

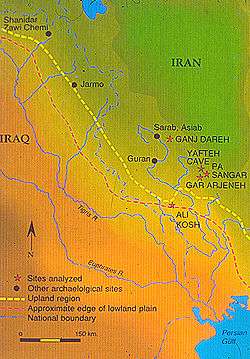

Map showing location of Ali Kosh and other locations of early herding activity | |

Neolithic sites in Iran | |

| Location | Ilam Province |

|---|---|

| Region | Iran |

| Diameter | 135 m |

| History | |

| Cultures | Pre-Pottery Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Discovered | 1960s |

| Archaeologists |

|

Site

The site is about 135 m in diameter.[3]

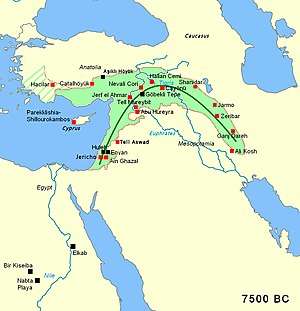

Research has found three phases of occupation of the site over an almost 2,000 period, starting from about 9,500 years ago (7500 BCE).[3] It was occupied originally by pre-pottery peoples.[4]

Pottery was introduced to Ali Kosh during the third phase of its occupation. Nearby Chogha Sefid has only one pre-pottery phase, after which the occupation extended into the Chalcolithic period.[5]

Earliest agriculture

Ali Kosh was the earliest agricultural community in western Iran, where emmer was already cultivated in the eighth millennium BC. This crop was not native to the area. Wild two-row hulled barley was also present. Goats and sheep were also herded.[6]

Similar site on the Deh Luran plain is Chogha Sefid, and also Tepe Abdul Hosein in Luristan. All three have similar stone tools. Ganj Dareh in Luristan (seen on the map), also similar, is even somewhat older than these.[7][8]

Genetic analysis

Human remains from the area have been analyzed in 2016 for their ancestry. Researchers sequenced the genome from a 30-50 year old woman from Ganj Dareh. mtDNA analysis shows that she belonged to Haplogroup X (mtDNA).[9]

Skull modification

In 2017, several skeletons were found by archaeologists in Ali Kosh. 7 crania were found, all showing the evidence of ritual cranial deformation.

- "The most striking feature of all crania was their more or less pronounced artificial deformation that was evident in spite of post-mortem alteration and fragmentation of all crania. In all cases circumferential modification was evident[10], resulting from application of a band wrapped around the cranium ... Artificial cranial deformation was common in the Near East and especially in Iran during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic[11]..."[12]

Previously, similar crania were already excavated in the area by Hole and Flannery.[13]

Ritual tooth avulsion

Another unusual cultural practice observed by researchers in these skulls was the ritual front tooth avulsion (removal of one or more teeth). Such a practice was quite common around the world in ancient times.[14]

- "Another cultural modification of the head observed at Ali Kosh was avulsion of the upper right first incisor in all adult males, but not in children nor adolescent individuals. ... Tooth avulsion was common during the Early Holocene in North Africa,[15] and it was also occasionally observed in the Natufian culture ..."[16]

According to these researchers, such a custom has not been previously reported for the eastern part of the Fertile Crescent.[17]

Relative chronology

References

- Hole, Frank. "Ali Kosh". Yale Campus Press. Yale University. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Darvill, Timothy (2008). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology (2nd ed.). Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199534043.001.0001. ISBN 9780191727139.

- Smith, Andrew Brown (2005). African herders: emergence of pastoral traditions. Rowman Altamira. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-7591-0748-9.

- Langer, William L. (1972). An Encyclopedia of World History (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 17. ISBN 0-395-13592-3. LCCN 72186219.

- Frank Hole (2004), NEOLITHIC AGE IN IRAN Archived 2012-10-23 at the Wayback Machine iranicaonline.org

- Mukhtar Ahmed, Ancient Pakistan - An Archaeological History: Volume II: A Prelude to Civilization. 2014, pp.214-215

- Mukhtar Ahmed, Ancient Pakistan - An Archaeological History: Volume II: A Prelude to Civilization. 2014, pp.214-215

- Frank Hole (2004), NEOLITHIC AGE IN IRAN Archived 2012-10-23 at the Wayback Machine iranicaonline.org

- Gallego-Llorente, M.; et al. (2016). "The genetics of an early Neolithic pastoralist from the Zagros, Iran". Scientific Reports. 6: 31326. doi:10.1038/srep31326. PMC 4977546. PMID 27502179.

- Frieß & Baylac 2003

- Meiklejohn et al. 1992; Daems & Croucher 2007

- Arkadiusz Sołtysiak*1, Hojjat Darabi, Human remains from Ali Kosh, Iran, 2017. Bioarchaeology of the Near East, 11:76–83 (2017) Short fieldwork report.

- Hole F., Flannery K.V., Neely J.A. (1969), Prehistory and human ecology of the Deh Luran plain. An early village sequence from Khuzistan, Iran, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- Pinchi, Vilma; Barbieri, Patrizia; Pradella, Francesco; Focardi, Martina; Bartolini, Viola; Norelli, Gian-Aristide (2015). "Dental Ritual Mutilations and Forensic Odontologist Practice: a Review of the Literature". Acta Stomatologica Croatica. 49 (1): 3–13. doi:10.15644/asc49/1/1. ISSN 0001-7019.

- Stojanowskiet al. 2014; De Groote & Humphrey 2016

- Arkadiusz Sołtysiak, Hojjat Darabi, Human remains from Ali Kosh, Iran, 2017. Bioarchaeology of the Near East, 11:76–83 (2017) Short fieldwork report.

- Arkadiusz Sołtysiak, Hojjat Darabi, Human remains from Ali Kosh, Iran, 2017. Bioarchaeology of the Near East, 11:76–83 (2017) Short fieldwork report.

- Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 13, Table 1.1 "Chronology of the Ancient Near East". ISBN 9781134750917.

- Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (7 May 2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4012948. PMID 24806472.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428.

- Thorpe, I. J. (2003). The Origins of Agriculture in Europe. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 9781134620104.

- Price, T. Douglas (2000). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521665728.

- Jr, William H. Stiebing; Helft, Susan N. (2017). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 9781134880836.

Bibliography

- F. Hole and K. V. Flannery, The Prehistory of Southwestern Iran: A Preliminary Report, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 33, 1968

- F. Hole, K. V. Flannery, and J. A. Neely, Prehistory and Human Ecology of the Deh Luran Plain. Memòria 1, Ann Arbor, 1969.

- F. Hole, Studies in the Archeological History of the Deh Luran Plain. Memòria 9, Ann Arbor, 1977