Shortugai

Shortugai (Shortughai) was a trading colony of the Indus Valley Civilization (or Harappan Civilization) established around 2000 BC on the Oxus river (Amu Darya) near the lapis lazuli mines in northern Afghanistan.[1][2] It is considered to be the northernmost settlement of the Indus Valley Civilization.[3][4] According to Bernard Sergent, "not one of the standard characteristics of the Harappan cultural complex is missing from it".[5]

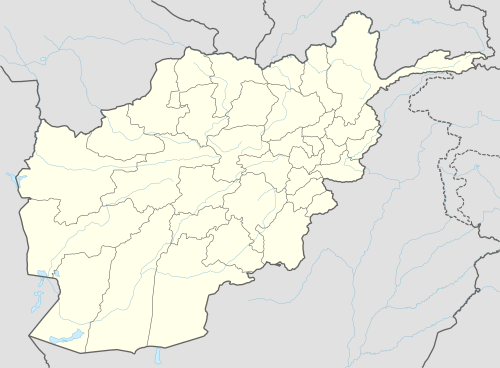

Shown within Afghanistan | |

| Location | Takhar Province, Afghanistan |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°19′30″N 69°31′30″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | Approximately 4 ha (9.9 acres) |

| History | |

| Cultures | Indus Valley Civilization |

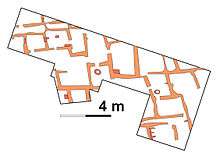

The town consists of two hills called A and B by the excavators. One of them was once the town proper, the other one the citadel. Each of them is about 2 hectares large.

Findings

The Shortugai site was discovered in 1976 and, since then, excavators were able to find carnelian and lapis lazuli beads, bronze objects, terracotta figurines.[6] Other typical finds of the Indus Valley Civilization include one seal with a short inscription[7] and a rhinoceros motif,[6] clay models of cattle with carts[8] and painted pottery.[9] Pottery with Harappan design, jars, beakers, bronze objects, gold pieces, lapis lazuli beads, other types of beads, drill heads, shell bangles etc. are other findings.[10] Square seals with animal motiff and script confirms this as a site belonging to Indus Valley Civilisation (not just having contact with IVC).[10] Bricks had typical Harappan measurements.

Dryland farming

A ploughed field with flax seeds in this site indicate dry land farming and irrigation canals dug to bring water from Kokcha (25 km distance) also indicate efforts put in agriculture.[10] There are several theories that explain the existence of canal irrigation system in the area. The first involves the suggestion that the Indus settlers brought the technology with them.[11] Another theory proposes that the canal was part of the influence of the Namazga culture, which flourished in the adjacent southern Turkmenia.[11]

Trading post

Shortugai was a trading post of Harappan times and it seems to be connected with lapis lazuli mines located in the surrounding area.[10] It also might have connections with tin trade (found at Afghanistan) and camel trade,[10] along with other Afghan valuables.[12] There are archaeologists who raise the issue of the absence of coinage and of an agreed decipherment despite the extensive trade networks controlled and operated by the settlement.[6]

References

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1998). Ancient cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 0-19-577940-1.

Another source of gold was along the Oxus river valley in northern Afghanistan where a trading colony of the Indus cities has been discovered at Shortughai. Situated far from the Indus Valley itself, this settlement may have been established to obtain gold, copper, tin and lapis lazuli, as well as other exotic goods from Central Asia.

- Bowersox, Gary W.; Chamberlin, Bonita E. Ph. D. (1995). "Gemstones of Afghanistan". Tucson, AZ: Geoscience Press: 52. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). "During the height of the Indus valley civilization about 2000 B.C., the Harappan colony of Shortugai was established near the lapis mines." - Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2016-05-27). A History of India. Routledge. ISBN 9781317242123.

- Oriens antiquus. Centro per le antichità e la storia dell'arte del Vicino Oriente. 1986.

- Bernard Sergent. Genèse de l'Inde, quoted by Elst 1999

- Robinson, Andrew (2015). The Indus: Lost Civilizations. London: Reaktion Books. p. 92. ISBN 9781780235028.

- Francfort: Fouilles de Shortughai, pl. 75, no. 7

- Francfort: Fouilles de Shortughai, pls. 81-82

- Francfort: Fouilles de Shortughai, pls. 59-61

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 169. ISBN 9788131711200.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 115. ISBN 9781576079072.

- McIntosh, Jane (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 135. ISBN 1576079651.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shortugai. |

- Henri-Paul Francfort: Fouilles de Shortughai, Recherches sur L'Asie Centrale Protohistorique Paris: Diffusion de Boccard, 1989