Hunza Valley

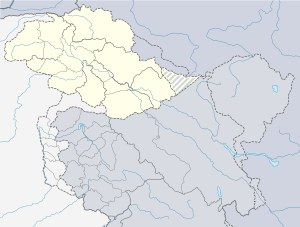

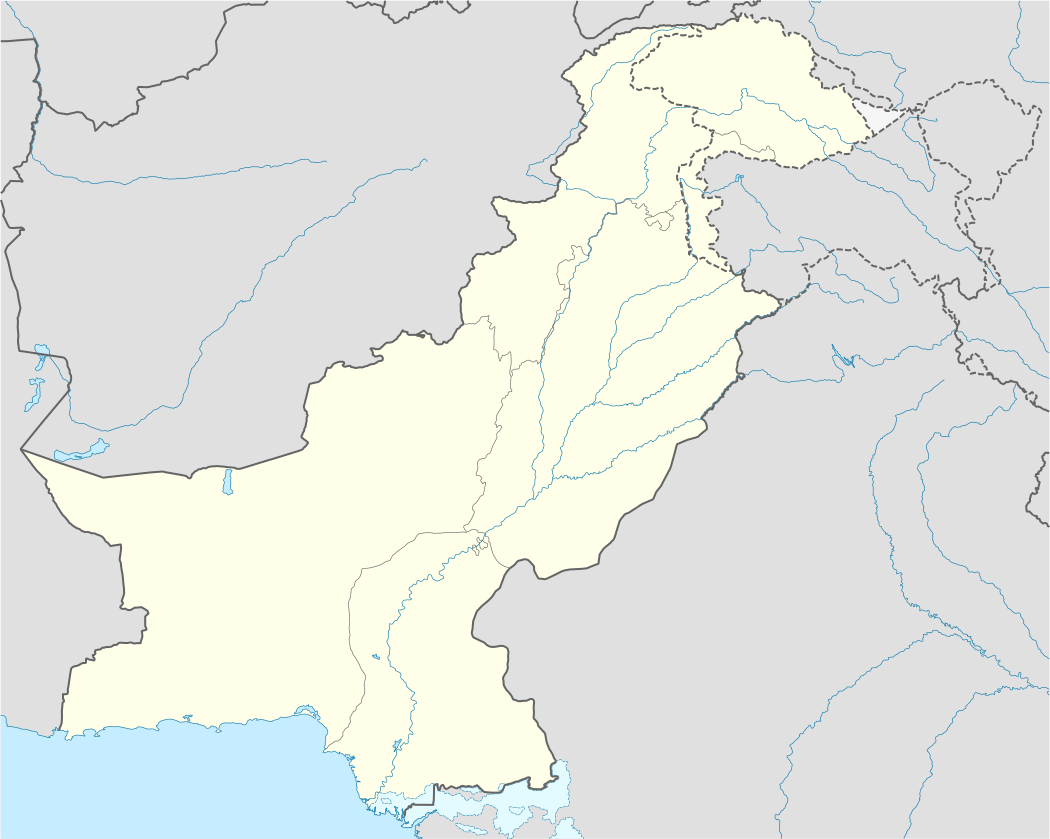

Hunza (Burushaski: ہنزو, Wakhi: "shina") is a mountainous valley in the autonomous Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan. Hunza is situated in the northern part of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan, bordering with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the west and the Xinjiang region of China to the north-east.[2]

| Hunza Valley | |

|---|---|

.jpg) The 7,788 metres (25,551 ft) tall Rakaposhi mountain towers over Hunza | |

Hunza Valley  Hunza Valley | |

| Naming | |

| Native name | ہنزو (Burushaski) |

| Geography | |

| Country | |

| State/Province | |

| District | Hunza District |

| Coordinates | 36.316942°N 74.649900°E [1] |

The Hunza valley is situated at an elevation of 2,438 meters (7,999 feet). Geographically, Hunza consists of three regions, Upper Hunza (Gojal), Central Hunza ("Hunza Valley") and Lower Hunza ("Shinaki").

History

The earliest history of the Hunza Valley can be traced to the ancient Indian epic Mahabharata.[3] During the Mahajanapada era of ancient India, the area came under the influence of several major ancient Indian kingdoms, mainly the Kingdom of Kapisa, Gandhara and possibly Magadha, among others. Buddhism came to the Hunza Valley in the late 7th century.

Buddhism and Bön, to a lesser extent, were the main religions in the area. The region has a number of surviving Buddhist archaeological sites such as the Sacred Rock of Hunza. Nearby are former sites of Buddhist shelters. Hunza valley was central as a trading route from Central Asia to the subcontinent. It also provided shelter to Buddhist missionaries and monks who were visiting the subcontinent, and the region played a major role in the transmission of Buddhism throughout Asia.[4]

The region was Buddhist majority till the 15th century, before the arrival of Islam in this region. Since then most of the people converted to Islam, the presence of Buddhism in this region has now been limited to archeological sites, as the remaining Buddhists of this region moved east to Leh where Buddhism is the majority religion. The region has many works of graffiti in the ancient Brahmi script written on rocks, produced by Buddhist monks as a form of worship and culture.[5] With the majority of locals converting to Islam, they had been left largely ignored, destroyed or forgotten, but are now being restored.[6]

Hunza was formerly a princely state bordering Xinjiang (autonomous region of China) to the northeast and Pamir to the northwest, which survived until 1974, when it was finally dissolved by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. The state bordered the Gilgit Agency to the south and the former princely state of Nagar to the east. The state capital was the town of Baltit (also known as Karimabad); another old settlement is Ganish Village which means "ancient gold" village. Hunza was an independent principality for more than 900 years until the British gained control of it and the neighboring valley of Nagar between 1889 and 1891 through military conquest. The then Tham (ruler), branch of Katur Dynasty, Safdar Khan of Hunza fled to Kashghar in China and sought what would now be called political asylum.[7]

Mir/Tham

An account wrote by John Biddulph in his book Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh

The ruling family of Hunza is called Ayesha (heavenly). The two states of Hunza and Nagar were formerly one, ruled by a branch of the Shahreis, the ruling family of Gilgit, whose seat of government was Nager. First muslim came to Hunza-Nagar Valley some 1000 years (At the time of Imam Islām Shāh 30th Imam Ismaili Muslims). After the introduction of Islam to Gilgit, married a daughter of Trakhan of Gilgit, who bore him twin sons, named Moghlot and Girkis. From the former, the present ruling family of Nager is descended. The twins are said to have shown hostility to one another from birth. Thereupon their father, unable to settle the question of succession, divided his state between them, giving Girkis the north/west, and to Moghlot the south/east bank of the river.[8]

2010 Landslide

On January 4, 2010, a landslide blocked the river and created Attabad Lake (also called shishket Lake), resulting in 20 deaths and 8 injuries and has effectively blocked about 26 kilometres (16 mi) of the Karakoram Highway.[9][10] The new lake extends 30 kilometres (19 mi) and rose to a depth of 400 feet (120 m) when it was formed as the Hunza River backed up.[11] The landslide completely covered sections of the Karakoram Highway.[11]

2018 Rescue mission

On 1 July 2018, Pakistan Army pilots in a daring mission rescued 3 foreign mountaineers stuck in snow avalanche at above the height of 19,000 feet (5,800 m) on Ultar Sar Peak near Hunza. The perilous weather conditions had made it difficult for the Army helicopter to go forth with a rescue operation on the 7,388 metres (24,239 ft) high Ultar Sar. But they completed it. Bruce Normand and Timothy Miller from UK were successfully rescued alive while their companion Christian Huber from Austria had succumbed to avalanche.[12][13]

Britain's High Commissioner Thomas Drew in Pakistan termed the mission “remarkable and dangerous” and said:

“Our gratitude to the Pakistan Army pilots who rescued two British climbers trapped by an avalanche on Ultar Sar Peak near Hunza. Our thoughts are with their Austrian fellow climber who died”. [14][15]

People

The local languages spoken include Burushaski, Wakhi and Shina. The literacy rate of the Hunza valley is more than 95%.[16] The historical area of Hunza and present northern Pakistan has had, over the centuries, mass migrations, conflicts and resettling of tribes and ethnicities, of which the Dardic Shina race is the most prominent in regional history. People of the region have recounted their historical traditions down the generations. The Hunza Valley is also home to some Wakhi, who migrated there from northeastern Afghanistan beginning in the nineteenth century onwards.[17]

The longevity of Hunza people has been noted by some,[18] but others refute this as a longevity myth caused by the lack of birth records.[19] There is no evidence that Hunza life expectancy is significantly above the average of poor, isolated regions of Pakistan. Claims of health and long life were almost always based solely on the statements by the local mir (king). An author who had significant and sustained contact with Burusho people, John Clark, reported that they were overall unhealthy.[20]

See also

- State of Hunza (former)

- Hunza–Nagar District

- Bagrot Valley

- Naltar Valley

- Shamanism in Hunza

- Northern Areas (former)

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Karakoram Highway

- Karakoram Mountains

- Neelam Valley

- Kalasha Valley

- Kaghan Valley

- Nagar Valley

References

- "Hunza on Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- "Mountainous Valley situated in the northern part of Pakistan". www.dreamstime.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Suryavanshi, Bhagwan Singh (1986). Geography of the Mahabharata. Ramanand Vidya Bhawan. p. 199.

- Behrendt, Kurt (2003). The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhāra. BRILL. p. 25. ISBN 978-90-474-1257-1.

- Susan E. Alcock; John Bodel; Richard J. A. Talbert (15 May 2012). Highways, Byways, and Road Systems in the Pre-Modern World. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-470-67425-3.

- Zara Khan, Vandalized Buddhist inscriptions in Gilgit-Baltistan are now being restored, Mashable Pakistan, 28 May 2020.

- Valley, Hunza. "Hunza Valley". www.skardu.pk. Skardu.pk. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh by John Biddulph page 26

- Waheed, Abdul (4 January 2013). "The Attabad Landslide Disaster". Pamir Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "SHISHKET LAKE CRISES – 2010 – CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS" (PDF). ndma.gov.pk. NDMA. 27 July 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- Michael Bopp; Judie Bopp (May 2013). "Needed: a second green revolution in Hunza" (PDF). HiMaT. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015. Karakorum Area Development Organization (KADO), Aliabad

- "Pakistan Army Pilots rescued 3 foreign mountaineers". en.dailypakistan.com.pk. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "Mountainers News on Thenews.com.pk". www.thenews.com.pk. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- "Britain's High Commissioner in Pakistan admired Pak Army Pilots for rescued the two British Climbers". www.telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- "Major General Asif Ghafoor also tweeted about it". www.forces.net. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Siddiqui, Shahid. "Hunza disaster and schools". Dawn. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- Frembgen Wasim, Jurgen (2017). The Arts and Crafts of the Hunza Valley in Pakistan: Living Traditions in the Karakoram. Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-940520-6.

- Wrench, Dr Guy T (1938). The Wheel of Health: A Study of the Hunza People and the Keys to Health. 2009 reprint. Review Press. ISBN 978-0-9802976-6-9. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- Tierney, John (29 September 1996). "The Optimists Are Right". The New York Times.

- "Hunza – The Truth, Myths, and Lies About the Health and Diet of the "Long-Lived" People of Hunza, Pakistan, Hunza Bread and Pie Recipes". www.biblelife.org. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

Further reading

- Kreutzmann, Hermann, Karakoram in Transition: Culture, Development, and Ecology in the Hunza Valley, Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-547210-3

- Leitner, G. W. (1893): Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893: Being An Account of the History, Religions, Customs, Legends, Fables and Songs of Gilgit, Chilas, Kandia (Gabrial) Yasin, Chitral, Hunza, Nagar and other parts of the Hindukush, as also a supplement to the second edition of The Hunza and Nagar Handbook. And An Epitome of Part III of the author's “The Languages and Races of Dardistan.” First Reprint 1978. Manjusri Publishing House, New Delhi.

- Lorimer, Lt. Col. D.L.R. Folk Tales of Hunza. 1st edition 1935, Oslo. Three volumes. Vol. II, republished by the Institute of Folk Heritage, Islamabad. 1981.

- Sidkey, M. H. "Shamans and Mountain Spirits in Hunza." Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 53, No. 1 (1994), pp. 67–96.

- History of Ancient Era Hunza State By Haji Qudratullah Beg English Translation By Lt Col (Rtd) Saadullah Beg, TI(M)

- Wrench, Dr Guy T (1938), The Wheel of Health: A Study of the Hunza People and the Keys to Health, 2009 reprint, Review Press, ISBN 978-0-9802976-6-9, retrieved 12 August 2010

- Miller, Katherine, 'Schooling Virtue: Education for 'Spiritual Development' in Megan Adamson Sijapati and Jessica Vantine Birkenholtz, eds., Religion and Modernity in the Himalaya (London: Routledge, 2016).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hunza Valley. |