Japan–Philippines relations

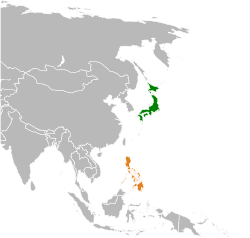

Japan–Philippines relations (Japanese: 日本とフィリピンの関係, Hepburn: Nihon to Firipin no kankei) and (Filipino: Ugnayang Pilipinas at Hapon), span a period from before the 16th century to the present.[1][2][3]

| |

Japan |

Philippines |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Japanese Embassy, Manila | Philippine Embassy, Tokyo |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Koji Haneda | Ambassador Jose C. Laurel V |

Early Japanese presence in the Philippines

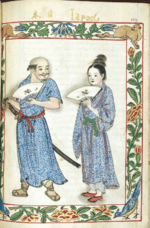

Relations between Japan and the kingdoms in the Philippines date back to at least the Muromachi period of Japanese history, as Japanese merchants and traders had settled in Luzon at this time. Especially in the area of Dilao, a district of Manila, was a Nihonmachi of 3,000 Japanese around the year 1600. The term probably originated from the Tagalog term 'dilaw', meaning 'yellow', which describes their general physiognomy. The Japanese had established quite early an enclave at Dilao where they numbered between 300 and 400 in 1593. In 1603, during the Sangley rebellion, they numbered 1,500, and 3,000 in 1606. In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of Japanese people traders also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[4] pp. 52–3

In 1593, Spanish authorities in Manila authorized the dispatch of Franciscan missionaries to Japan. The Franciscan friar Luis Sotelo was involved in the support of the Dilao enclave between 1600 and 1608.

In the first half of the 17th century, intense official trade took place between the two countries, through the Red seal ships system. Thirty official "Red seal ship" passports were issued between Japan and the Philippines between 1604 and 1616.[5]

The Japanese led an abortive rebellion in Dilao against the Spanish Empire in 1606–1607, but their numbers rose again until the interdiction of Christianity by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1614, when 300 Japanese Christian refugees under Takayama Ukon settled in the Philippines. On 8 November 1614, together with 300 Japanese Christians Takayama Ukon left his home country from Nagasaki. He arrived at Manila on 21 December and was greeted warmly by the Spanish Jesuits and the local Filipinos there. The Spanish Philippines offered its assistance in overthrowing the Japanese government by invasion to protect Japanese Catholics. Justo declined to participate and died of illness just 40 days afterward. These 17th-century immigrants are at the origin of some of today's 200,000-strong Japanese population in the Philippines.

More rebellions such as one known as the Tondo conspiracy had Japanese merchants and Christians involved, but the conspiracy was disbanded. Toyotomi Hideyoshi threatened the Spanish to leave or face full scale Japanese invasion, however, this was near his decline and death. The Tokugawa Shogunate rose in power right after.

By the mid-17th century, Japan established an isolationist (sakoku) policy, and contacts between the two nations were severed until after the opening of Japan in 1854. In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of Japanese traders also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[6]

Philippines and the Empire of Japan

During the 1896 uprising against Spanish colonial rule the 1898 Spanish–American War, some Filipino insurgents (especially the Katipunan) sought assistance from the Japanese government. The Katipunan sent a delegate to the Emperor of Japan to solicit funds and military arms in May 1896.[7][8] The Meiji government of Japan was unwilling and unable to provide any official support. However, Japanese supporters of Philippine independence in the Pan-Asian movement raised funds and sent weapons on the privately charted Nunobiki Maru, which sank before reaching its destination. However, the Japanese government officially acquiesced to American colonial rule over the Philippines, as ratified by the Taft–Katsura Agreement of 1905. During the American period, Japanese economic ties to the Philippines expanded tremendously and by 1929 Japan was the largest trading partner to the Philippines after the United States. Economic investment was accompanied by large-scale immigration of Japanese to the Philippines, mainly merchants, gardeners and prostitutes ('karayuki-san'). Davao that time had over 20,000 ethnic Japanese residents. In Baguio, Japanese workers represented about 22% of the workforce that constructed Benguet Road (later renamed Kennon Road), so that Baguio later had a significant Japanese population.[9] By 1935, it was estimated that Japanese immigrants dominated 35% of Philippine retail trade. Investments included extensive agricultural holdings and natural resource development. By 1940, some 40% of Philippine exports to Japan were iron, copper, manganese and chrome.[10]

During World War II, immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces invaded and quickly overcame resistance by the United States and Philippine Commonwealth military. Strategically, Japan needed the Philippines to prevent its use by Allied forces as a forward base of operations against the Japanese home islands, and against its plans for the further conquest of Southeast Asia. In 1943, a puppet government, the Second Philippine Republic, was established, but gained little popular support, primarily due to the Imperial Japanese Army's brutal conduct towards the Philippine civilian population. During the course of the Japanese occupation, and subsequent battles during the American and Filipino re-invasion, an estimated one million Filipinos died, giving rise to lingering anti-Japanese sentiment.[11]

Hundreds of heritage cities and towns throughout the country lay in ruins due to intentional fire and kamikaze tactics imposed by the Japanese and bombings imposed by the Americans. Only a single heritage town, Vigan, survived. The government of the Empire of Japan never gave any compensation for the restoration of Filipino heritage towns and cities. While the United States only gave minimal funding for two cities, Manila and Baguio. A decade after the war, the heritage landscape of the Philippines was never restored due to a devastated economy, lack of funding, and lack of cultural experts during the time. The heritage zones were effectively replaced by old shanty houses and cement houses with cheap plywood or galvanized iron as roofs.[12] According to a United States analysis released years after the war, U.S. casualties were 10,380 dead and 36,550 wounded; Japanese dead were 255,795. Filipino deaths, on the other hand, has no official count but was estimated to be more than one million, an astounding percentage of the national population at the time. The Philippine population decreased continuously for the next 5 years due to the spread of diseases and the lack of basic needs, far from Filipino lifestyle prior to the war where the country used to be the second richest in Asia, ironically, next only to Japan.[12]

Post-war relations

The Philippines was granted independence by the United States in 1946, and was a signatory to the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty with Japan. Diplomatic relations were normalized and re-established in 1956, when a war reparations agreement was concluded. By the end of the 1950s, Japanese companies and individual investors had begun to return to the Philippines.

Japan and the Philippines signed a Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation in 1960, but the treaty did not go into effect until 1973.

Relations during the Marcos dictatorship

Hirohito met with President Ferdinand Marcos in a state visit by the latter to Japan in 1966[13] - a year after Marcos' election and about six years before Marcos declared martial law.

In 1972, Marcos abolished the Philippine legislature under martial law, and took on its legislative powers as part of his authoritarian rule. He ratified the Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation ten days prior to a visit of Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka.

By 1975, Japan had displaced the United States as the main source of investment in the country. Marcos administration projects put up during this time include the Philippines-Japan Friendship Highway which included the construction of the San Juanico Bridge, and the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine. However, many of these projects were later criticized for helping prop up the corrupt practices of the Marcos administration, resulting in what became called the Marukosu giwaku (マルコス疑惑), or "Marcos scandal", of 1986.[14]

Japan ODA scandal

When the Marcoses were exiled to Hawaii in the United States in February 1986 after the People Power Revolution,[15] the American authorities confiscated papers that they brought with them. The confiscated documents revealed that since the 1970s, Marcos and his associates received commissions of 10 to 15 percent of Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund loans from about fifty Japanese contractors.

This revelation became known as the Marukosu giwaku (マルコス疑惑), or "Marcos scandals",[14] and had to be addressed by the administrations of succeeding presidents Corazon Aquino and Fidel V. Ramos. The Japanese government discreetly requested the Philippine government to downplay the issue as it would affect the business sector and bilateral relations.[16]

The lessons from the Marcos scandals were among the reasons why Japan created its 1992 ODA Charter.[15]

After 1986

Japan remained a major source of development funds, trade, investment, and tourism in the 1980s, and there have been few foreign policy disputes between the two nations.

When Philippine President Corazon Aquino's administration was installed as a result of the People Power Revolution, Japan was one of the first countries to express support for the new Philippine government.[17]

Philippine President Corazon Aquino visited Japan in November 1986 and met with Emperor Hirohito, who offered his apologies for the wrongs committed by Japan during World War II. New foreign aid agreements also were concluded during this visit. Aquino returned to Japan in 1989 for Hirohito's funeral and in 1990 for the enthronement of Emperor Akihito.

Regarding the voting of the Philippine Senate to extend a treaty allowing the stay of U.S. bases in the Philippines, Japan was in favor for the extension of the defense treaty. In fact, some of its officials including Ambassador Toshio Goto, Foreign Minister Taro Nakayama and Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu expressed public disagreement on a negative vote on the extension. However the Philippine Senate rejected the extension of the defense treaty despite extensive lobbying for its extension by the first Aquino administration, even calling for a referendum regarding the matter.[18][19] In 1998, 246,000 Filipinos lived in Japan.[20]

Upon the withdrawal of most American troops in the Philippines, relations between the United States and the Philippines remained strong as assured by US President Bill Clinton to Philippine President Fidel V. Ramos during the latter's visit to Washington on 21 November 1993. Likewise the Philippines-Japan relations were strengthened with Japan filling the gap the United States left. Even before Ramos became president he held talks with the Japan Ministry of Defense to improve defense relations as Defense Secretary under Corazon Aquino's administration. [21]

During a meeting with President Ramos in 1993, Japanese Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa reiterated his apology for his country's war crimes committed against the Philippines and its people during World War II and would consider the best way to address the issue. The Ramos administration also supported Japan's bid to become a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, together with Germany.[22]

Japan also became the top donor of aid to the Philippines, followed by the United States and Germany. Japan also contributed the largest amount of international aid to the Philippines after the latter suffered from the 1990 Luzon earthquake and 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption. In 2009, Japan supported an NGO which repatriated the skeletons of Japanese soldiers from World War II. The NGO repatriated numerous skeletons of indigenous Filipino ancestors, along with few Japanese skeletons, causing rallies in the Philippines. Japan ended its support for the skeleton repatriation program afterwards, however, the remains of the indigenous Filipinos were never sent back to the ancestral communities they were stolen from.[23]

Strategic relationship between the two countries has been strong recently. Japan supports the resolution of the Islamic insurgency in the Philippines.[24] In 2013, Japan announced it would donate ten ships valued at US$11 million to the Philippine Coast Guard. Japan and the Philippines share a "mutual concern" on China's increasing assertiveness in its territorial claims.[25][26]

In November 2015, the Philippine government and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) signed a $2-billion loan agreement for the JICA to fund part of the construction of a railway system between the Tutuban railway station in Manila to Malolos, Bulacan in the Philippines, which is targeted to become the country's largest railway system. According to the Philippine Department of Finance, the agreement was the JICA's "largest assistance ever extended to any country for a single project."[27][28]

On February 29, 2016, Japan Signed a pact to supply defense equipment to Philippines. The agreement provides a framework for the supply of defense equipment and technology and will allow the two countries to carry out joint research and development projects.[29][30] On April 3, 2016, Japanese training submarine JS Oyashio, along with two destroyers JS Ariake and JS Setogiri docked at the Alava Pier in Subic Bay for a three-day goodwill visit.[31] In early May 2016, plans to spearhead a Japan-Philippine Mutual Defense Treaty was one of the key defense plans of the government if Mar Roxas wins the presidency. However, the May 10 presidential elections resulted to the presidential victory of Rodrigo Duterte.[32] In October, 2016, talks about the defense treaty was revived when the government stated that the possible treaty 'may' be discussed by Duterte and Abe during Duterte's first official visit to Japan. The visit however resulted in no talks regarding the possible treaty after Duterte decided to ally himself with China.[33]

In 2017, a blindfolded Filipina comfort women statue was erected in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. It was later confirmed that the erection of the statue was partly funded by Chinese businessmen who Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte was wooing for loans. Majority of Filipinos support the installation of the statue, but disapprove its Chinese-funded origins.[34] By April 2018, the comfort woman statue was removed from the capital after Duterte met with Japanese diplomats.[35]

Country comparison

See also

- Japanese in the Philippines

- Japanese occupation of the Philippines

- Filipinos in Japan

- Dom Justo Takayama (Takayama Ukon)

- Domingo Siazon

- Marcos scandals

- Taft–Katsura Agreement

- Diwata (satellite)

References

- Hisona, Harold (14 July 2010). "The Cultural Influences of India, China, Arabia, and Japan". Philippine Almanac. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- "Ancient Japanese pottery in Boljoon town". Philippine Daily Inquirer. 30 May 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- "Philippines History, Culture, Civilization and Technology, Filipino". Asiapacificuniverse.com. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Leupp, Gary P. (1 January 2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan: Western Men and Japanese Women, 1543-1900. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826460745 – via Google Books.

-

- Boxer, C.R., The Christian Century in Japan, 2001 Carcanet, Manchester, ISBN 1-85754-035-2 p.264

- Leupp, Gary P. (1 January 2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan: Western Men and Japanese Women, 1543-1900. A&C Black. ISBN 9780826460745 – via Google Books.

- "History Of Katipunan - Home On The Net". Katipunan.weebly.com. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Afable, Patricia (2008). "Compelling Memories and Telling Archival Documents and Photographs: The Search for the Baguio Japanese Community" (PDF). Asian Studies. 44 (1).

- Lydia N. Yu-Jose, Japan Views the Philippines, 1900-1944 (1999)

- Sven Matthiessen, Japanese Pan-Asianism and the Philippines from the Late Nineteenth Century to the End of World War II: Going to the Philippines Is Like Coming Home? (Brill, 2015).

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War 2 Pacific island guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- "Marcos arrives for Japan visit". 30 September 1966. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- Hirata, K. (16 August 2002). Civil Society in Japan: The Growing Role of NGO's in Tokyo's Aid and Development Policy. Springer. ISBN 9780230109162.

- Brown, James D. J.; Kingston, Jeff (2 January 2018). Japan's Foreign Relations in Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9781351678575.

- Ikehata, Setsuho; Yu-Jose, Lydia, eds. (2003). Philippines-Japan Relations. Ateneo De Manila University Press. p. 591. ISBN 978-971-550-436-2.

- Ikehata, Setsuho; Yu-Jose, Lydia, eds. (2003). Philippines-Japan Relations. Ateneo De Manila University Press. p. 580. ISBN 978-971-550-436-2.

- DAVID E. SANGER (28 December 1991). "Philippines Orders U.S. to Leave Strategic Navy Base at Subic Bay - New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Ikehata, Setsuho; Yu-Jose, Lydia, eds. (2003). Philippines-Japan Relations. Ateneo De Manila University Press. p. 584. ISBN 978-971-550-436-2.

- David Levinson, ed.., Encyclopedia of Modern Asia (2002) 3:243

- Ikehata, Setsuho; Yu-Jose, Lydia, eds. (2003). Philippines-Japan Relations. Ateneo De Manila University Press. pp. 579, 585. ISBN 978-971-550-436-2.

- Ikehata, Setsuho; Yu-Jose, Lydia, eds. (2003). Philippines-Japan Relations. Ateneo De Manila University Press. pp. 588, 593. ISBN 978-971-550-436-2.

- Ikehata, Setsuho; Yu-Jose, Lydia, eds. (2003). Philippines-Japan Relations. Ateneo De Manila University Press. pp. 580–581. ISBN 978-971-550-436-2.

- "Visit to Japan of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Peace Negotiating Panel". MOFA. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Julius Cesar I Trajano (14 March 2013). "Japan and Philippines align strategic interests". Asian Times. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Japan-Philippine Relations: New Dynamics In Strategic Partnership - Analysis Eurasia Review". Eurasiareview.com. 5 March 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- de Vera, Ben (28 November 2015). "PH, Japan agency sign $2-B railway loan". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Magtulis, Prinz (27 November 2015). "Japan's $2-B loan to fund Philippines's largest railway system". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- "International News: Latest Headlines, Video and Photographs from Around the World -- People, Places, Crisis, Conflict, Culture, Change, Analysis and Trends". ABC News.

- "Japan signs pact to supply defense equipment to Philippines".

- "Japanese submarine, destroyers dock in Subic". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- Lopez, Bernie V. "Needed: PH-Japan defense treaty". Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- "PH-Japan defense treaty may be discussed in Duterte visit". CNN Philippines. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- II, Paterno Esmaquel. "What's wrong with this statue of a comfort woman in Manila?". Rappler.

- "Comfort woman statue in Manila removed". Rappler. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

![]()

Further reading

- Ikehata, Setsuho and Lydia Yu-Jose, eds. Philippines-Japan Relations ( Ateneo De Manila University Press, 2003) .

- Tana, Maria Thaemar, and Yusuke Takagi. "Japan’s foreign relations with the Philippines: A case of evolving Japan in Asia." in James D.J. Brown and Jeff Kingston, eds. Japan's Foreign Relations in Asia (Routledge, 2018) pp. 312–328.

- Trinidad, Dennis D. "Domestic Factors and Strategic Partnership: Redefining Philippines‐Japan Relations in the 21st Century." \\Asian Politics & Policy 9.4 (2017): 613-635. online

- Trinidad, Dennis D. "Towards strategic partnership: Philippines–Japan relations after seventy years." in Mark R. Thompson, Eric Vincent C. Batalla, eds. Routledge Handbook of the Contemporary Philippines ( Routledge, 2018) pp. 186-196.

- Yu-Jose, Lydia N. "World War II and the Japanese in the prewar Philippines." Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27#1 (1996): 64–81. Online