India–Japan relations

India–Japan relations have traditionally been strong. The people of India and Japan have engaged in cultural exchanges, primarily as a result of Buddhism, which spread indirectly from India to Japan, via China and Korea. The people of India and Japan are guided by common cultural traditions including the heritage of Buddhism and share a strong commitment to the ideals of democracy, tolerance, pluralism and open societies. India and Japan, two of the largest and oldest democracies in Asia, having a high degree of congruence of political, economic and strategic interests, view each other as partners that have responsibility for, and are capable of, responding to global and regional challenges. India is the largest recipient of Japanese and both country have a special relationship official development assistance (ODA).[1] As of 2017, bilateral trade between India and Japan stood at US$17.63 billion.

| |

India |

Japan |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of India, Tokyo, Japan | Embassy of Japan, New Delhi, India |

| Envoy | |

| Indian Ambassador to Japan Sanjay Kumar Verma | Japanese Ambassador to India Satoshi Suzuki |

The British occupiers of India and Japan were enemies during World War II, but political relations between the two nations have remained warm since India's independence. Japanese companies, such as Yamaha, Sony, Toyota, and Honda have manufacturing facilities in India. With the growth of the Indian economy, India is a big market for Japanese firms. Japanese firms were some of the first firms to invest in India. The most prominent Japanese company to have an investment in India is automobiles multinational Suzuki, which is in partnership with Indian automobiles company Maruti Suzuki, the largest car manufacturer in the Indian market, and a subsidiary of the Japanese company.

In December 2006, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's visit to Japan culminated in the signing of the "Joint Statement Towards Japan-India Strategic and Global Partnership". Japan has helped finance many infrastructure projects in India, most notably the Delhi Metro system. Indian applicants were welcomed in 2006 to the JET Programme, with one slot available in 2006 and increasing to 41 slots in 2007. In 2007, the Japanese Self-Defence Forces and the Indian Navy took part in a joint naval exercise Malabar 2007 in the Indian Ocean, which also involved the naval forces of Australia, Singapore and the United States. 2007 was declared "India-Japan Friendship Year."[1]

According to a 2013 BBC World Service Poll, 42% Japanese think India's international impact is mainly positive, with 4% considering it negative.[2]

Historical relations

In my opinion, if all our rich and educated men once go and see Japan, their eyes will be opened.

— Swami Vivekananda, The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda/Volume 5/Conversations and Dialogues/VI – X Shri Priya Nath Sinha

Though Hinduism is a little-practiced religion in Japan, it has still had a significant, but indirect role in the formation of Japanese culture. This is mostly because many Buddhist beliefs and traditions (which share a common Dharmic root with Hinduism) spread to Japan from China via Korean peninsula in the 6th Century. One indication of this is the Japanese "Seven Gods of Fortune", of which four originated as Hindu deities: Benzaitensama (Sarasvati), Bishamon (Vaiśravaṇa or Kubera), Daikokuten (Mahākāla/Shiva), and Kichijōten (Lakshmi). Along with Benzaitennyo/Sarasvati and Kisshoutennyo/Laxmi and completing the nipponization of the three Hindu Tridevi goddesses, the Hindu goddess Mahakali is nipponized as the Japanese goddess Daikokutennyo (大黒天女), though she is only counted among Japan's Seven Luck Deities when she is regarded as the feminine manifestation of her male counterpart Daikokuten (大黒天).[3] Benzaiten arrived in Japan during the 6th through 8th centuries, mainly via the Chinese translations of the Sutra of Golden Light (金光明経), which has a section devoted to her. She is also mentioned in the Lotus Sutra. In Japan, the lokapālas take the Buddhist form of the Four Heavenly Kings (四天王). The Sutra of Golden Light became one of the most important sutras in Japan because of its fundamental message, which teaches that the Four Heavenly Kings protect the ruler who governs his country in the proper manner. The Hindu god of death, Yama, is known in his Buddhist form as Enma. Garuda, the mount (vahana) of Vishnu, is known as the Karura (迦楼羅), an enormous, fire-breathing creature in Japan. It has the body of a human and the face or beak of an eagle. Tennin originated from the apsaras. The Hindu Ganesha (see Kangiten) is displayed more than Buddha in a temple in Futako Tamagawa, Tokyo. Other examples of Hindu influence on Japan include the belief of "six schools" or "six doctrines" as well as use of Yoga and pagodas. Many of the facets of Hindu culture which have influenced Japan have also influenced Chinese culture. People have written books on the worship of Hindu gods in Japan.[4] Even today, it is claimed Japan encourages a deeper study of Hindu gods.[5]

Buddhism

Buddhism has been practiced in Japan since its official introduction in 552 CE according to the Nihon Shoki[6] from Baekje, Korea by Buddhist monks.[7][8] Although some Chinese sources place the first spreading of the religion earlier during the Kofun period (250 to 538). Buddhism has had a major influence on the development of Japanese society and remains an influential aspect of the culture to this day.[9]

Cultural exchanges between India and Japan began early in the 6th century with the introduction of Buddhism to Japan from India. The Indian monk Bodhisena arrived in Japan in 736 to spread Buddhism and performed eye-opening of the Great Buddha built in Tōdai-ji,[1] and would remain in Japan until his death in 760. Buddhism and the intrinsically linked Indian culture had a great impact on Japanese culture, still felt today, and resulted in a natural sense of amiability between the two nations.[10]

As a result of the link of Buddhism between India and Japan, monks and scholars often embarked on voyages between the two nations.[11] Ancient records from the now-destroyed library at Nalanda University in India describe scholars and pupils who attended the school from Japan.[12] One of the most famous Japanese travellers to the Indian subcontinent was Tenjiku Tokubei (1612–1692), named after Tenjiku ("Heavenly Abode"), the Japanese name for India.

The cultural exchanges between the two countries created many parallels in their folklore. Modern popular culture based upon this folklore, such as works of fantasy fiction in manga and anime, sometimes bear references to common deities (deva), demons (asura) and philosophical concepts. The Indian goddess Saraswati for example, is known as Benzaiten in Japan. Brahma, known as 'Bonten', and Yama, known as 'Enma', are also part of the traditional Japanese Buddhist pantheon. In addition to the common Buddhist influence on the two societies, Shintoism, being an animist religion, is similar to the animist strands of Hinduism, in contrast to the religions present in the rest of the world, which are monotheistic. Sanskrit, a classical language used in Buddhism and Hinduism, is still used by some ancient Chinese priests who immigrated to Japan, and the Siddhaṃ script is still written to this day, despite having passed out of usage in India. It is also thought that the distinctive torii gateways at temples in Japan, may be related to the torana gateways used in Indian temples.

In the 16th century, Japan established political contact with Portuguese colonies in India. The Japanese initially assumed that the Portuguese were from India and that Christianity was a new "Indian faith". These mistaken assumptions were due to the Indian city of Goa being a central base for the Portuguese East India Company and also due to a significant portion of the crew on Portuguese ships being Indian Christians.[13] Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, Indian lascar seamen frequently visited Japan as crew members aboard Portuguese ships, and later aboard British ships in the 18th and 19th centuries.[14]

During the anti-Christian persecutions in 1596, many Japanese Christians fled to the Portuguese colony of Goa in India. By the early 17th century, there was a community of Japanese traders in Goa in addition to Japanese slaves brought by Portuguese ships from Japan.[15]

Relations between the two nations have continued since then, but direct political exchange began only in the Meiji era (1868–1912), when Japan embarked on the process of modernisation.[16] Japan-India Association was founded in 1903.[17] Further cultural exchange occurred during the mid-late 20th century through Asian cinema, with Indian cinema and Japanese cinema both experiencing a "golden age" during the 1950s and 1960s. Indian films by Satyajit Ray, Guru Dutt were influential in Japan, while Japanese films by Akira Kurosawa, Yasujirō Ozu and Takashi Shimizu have likewise been influential in India.

Indian Independence Movement

Japan's emergence as a power in the early 20th century was positively viewed in India and symbolised what was seen as the beginning of an Asian resurgence. In India, there was great admiration for Japan's post-war economic reconstruction and subsequent rapid growth.[18]Sureshchandra Bandopadhyay, Manmatha Nath Ghosh and Hariprova Takeda were among the earliest Indians who visited Japan and had written on their experiences there.[19] Correspondences between distinguished individuals from both nations had a noticeable increase at the time; historical documents show a friendship between Japanese thinker Okakura Tenshin and Indian writer Rabindranath Tagore, Okakura Tenshin and Bengali poet Priyamvada Banerjee.[20] As part of the British Empire, many Indians resented the British rule. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance was ended on 17 August 1923. As a result, during the two World Wars, the INA adopted the "an enemy of our enemy is our friend" attitude, legacy that is still controversial today given the war crimes committed by Imperial Japan and its allies.

Many Indian independence movement activists escaped from British rule and stayed in Japan. The leader of the Indian Independence Movement, Rash Behari Bose created India–Japan relations. Future prime minister Tsuyoshi Inukai, pan-Asianist Mitsuru Tōyama and other Japanese supported the Indian Independence movement. A. M. Nair, a student from India, became an Independence Movement activist. Nair supported Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose during the war and Justice Radha Binod Pal after the war.

In 1899 Tokyo Imperial University set up a chair in Sanskrit and Pali, with a further chair in Comparative religion being set up in 1903. In this environment, a number of Indian students came to Japan in the early twentieth century, founding the Oriental Youngmen's Association in 1900. Their anti-British political activity caused consternation to the Indian Government, following a report in the London Spectator.

During World War II

Since India was under British rule when World War II broke out, it was deemed to have entered the war on the side of the Allies. Over 2 million Indians participated in the war; many served in combat against the Japanese who conquered Burma and reached the Indian border. Some 67,000 Indian soldiers were captured by the Japanese when Singapore surrendered in 1942, many of whom later became part of the Japanese sponsored Indian National Army (INA). In 1944–45, combined British and Indian forces defeated the Japanese in a series of battles in Burma and the INA disintegrated.[21]

Indian National Army

Subhas Chandra Bose, who led the Azad Hind, a nationalist movement which aimed to end the British Raj in India through military means, used Japanese sponsorship to form the Azad Hind Fauj or Indian National Army (INA). The INA was composed mainly of former prisoners of war from the British Indian Army who had been captured by the Japanese after the fall of Singapore. They joined primarily because of the very harsh, often fatal conditions in POW camps. The INA also recruited volunteers from Indian expatriates in Southeast Asia. Bose was eager for the INA to participate in any invasion of India, and persuaded several Japanese that a victory such as Mutaguchi anticipated would lead to the collapse of British rule in India. The idea that their western boundary would be controlled by a more friendly government was attractive. Japan never expected India to be part of its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.[22]

The Japanese Government built, supported and controlled the Indian National Army and the Indian Independence League. Japanese forces included INA units in many battles, most notably at the U Go Offensive at Manipur. The offensive culminated in Battles of Imphal and Kohima where the Japanese forces were pushed back and the INA lost cohesion.

Modern relations

At the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, Indian Justice Radhabinod Pal became famous for his dissenting judgement in favour of Japan. The judgement of Justice Radhabinod Pal is remembered even today in Japan.[1] This became a symbol of the close ties between India and Japan.

A relatively well-known result of the two nations' was in 1949, when India sent the Tokyo Zoo two elephants to cheer the spirits of the defeated Japanese empire.[23][24]

India refused to attend the San Francisco Peace Conference in 1951 due to its concerns over limitations imposed upon Japanese sovereignty and national independence.[18][25] After the restoration of Japan's sovereignty, Japan and India signed a peace treaty, establishing official diplomatic relations on 28 April 1952, in which India waived all reparation claims against Japan.[18] This treaty was one of the first treaties Japan signed after World War II.[10] Diplomatic, trade, economic, and technical relations between India and Japan were well established. India's iron ore helped Japan's recovery from World War II devastation, and following Japanese Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi's visit to India in 1957, Japan started providing yen loans to India in 1958, as the first yen loan aid extended by Japanese government.[10] Relations between the two nations were constrained, however, by Cold War politics. Japan, as a result of World War II reconstruction, was a U.S. ally, whereas India pursued a non-aligned foreign policy, often leaning towards the Soviet Union. Since the 1980s, however, efforts were made to strengthen bilateral ties. India's ‘Look East’ policy posited Japan as a key partner.[18] Since 1986, Japan has become India's largest aid donor, and remains so.[10]

Relations between the two nations reached a brief low in 1998 as a result of Pokhran-II, an Indian nuclear weapons test that year. Japan imposed sanctions on India following the test, which included the suspension of all political exchanges and the cutting off economic assistance. These sanctions were lifted three years later. Relations improved exponentially following this period, as bilateral ties between the two nations improved once again,[26] to the point where the Japanese prime minister, Shinzo Abe was to be the chief guest at India's 2014 Republic Day parade.[27]

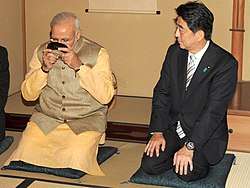

In 2014, the Indian PM Narendra Modi visited Japan. During his tenure as the Chief Minister of Gujarat, Modi had maintained good ties with the Japanese PM Shinzo Abe. His 2014 visit further strengthened the ties between the two countries, and resulted in several key agreements, including the establishment of a "Special Strategic Global Partnership".[28][29]

Modi visited Japan for the second time as Prime Minister in November 2016. During the meeting, India and Japan signed the "Agreement for Cooperation in Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy", a landmark civil nuclear agreement, under which Japan will supply nuclear reactors, fuel and technology to India. India is not a signatory to the non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), and is the only non-signatory to receive an exemption from Japan.[30] The two sides also signed agreements on manufacturing skill development in India, cooperation in space, earth sciences, agriculture, forestry and fisheries, transport and urban development.[31]

Yogendra Puranik , popularly known as Yogi, became the first elected India-born City Councillor in Japan, to represent the City Council of Edogawa City in Tokyo. His victory was well received by the mass public and media, not just in India and Japan but across the globe including China.

Economic

In August 2000, the Japanese Prime Minister visited India. At this meeting, Japan and India agreed to establish "Japan-India Global Partnership in the 21st Century." Indian Prime Minister Vajpayee visited Japan in December, 2001, where both Prime Ministers issued "Japan-India Joint Declaration." In April, 2005, Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi visited India and signed Joint Statement "Japan-India Partnership in the New Asian Era: Strategic Orientation of Japan-India Global Partnership."

Japan is the 3rd largest investor in the Indian economy with cumulative FDI inflows of $30.27 bn during 2000-2019, contributing 7.2% to India's total FDI inflows during the same period. The imports to India from Japan stood at $12.77 bn in 2018-19, making it India's 14th largest import partner.[32]

In October 2008, Japan signed an agreement with India under which it would provide the latter a low-interest loan worth US$4.5 billion to construct a railway project between Delhi and Mumbai. This is the single largest overseas project being financed by Japan and reflected growing economic partnership between the two nations. India is also one of the only three countries in the world with whom Japan has a security pact. As of March 2006, Japan was the third largest investor in India.

Kenichi Yoshida, a director of Softbridge Solutions Japan, stated in late 2009 that Indian engineers were becoming the backbone of Japan's IT industry and that "it is important for Japanese industry to work together with India". Under the memorandum, any Japanese coming to India for business or work will be straightway granted a three-year visa and similar procedures will be followed by Japan. Other highlights of this visit includes abolition of customs duties on 94 per cent of trade between the two nations over the next decade. As per the Agreement, tariffs will be removed on almost 90 per cent of Japan's exports to India and 97 per cent of India's exports to Japan Trade between the two nations has also steadily been growing.

India and Japan signed an agreement in December 2015 to build a bullet train line between Mumbai and Ahmedabad using Japan's Shinkansen technology,[33] with a loan from Japan of £12bn. More than four-fifths of the project’s $19bn (£14.4bn) cost will be funded by a 0.1% interest-rate loan from Japan as part of a deepening economic relationship.[34]

Military

India and Japan also have close military ties. They have shared interests in maintaining the security of sea-lanes in the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean, and in co-operation for fighting international crime, terrorism, piracy and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.[35] The two nations have frequently held joint military exercises and co-operate on technology.[18] India and Japan concluded a security pact on 22 October 2008.[36][37]

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is seen by some to be an "Indophile" and, with rising tensions in territorial disputes with Japan's neighbors, has advocated closer security cooperation with India.[38][39]

In July 2014, the Indian Navy participated in Exercise Malabar with the Japanese and US navies, reflecting shared perspectives on Indo-Pacific maritime security. India is also negotiating to purchase US-2 amphibious aircraft for the Indian Navy.[40]

Cultural

Japan and India have strong cultural ties, based mainly on Japanese Buddhism, which remains widely practiced through Japan even today. The two nations announced 2007, the 50th anniversary year of Indo-Japan Cultural Agreement, as the Indo-Japan Friendship and Tourism-Promotion Year, holding cultural events in both the countries.[41][42] One such cultural event is the annual Namaste India Festival, which started in Japan over twenty years ago and is now the largest festival of its kind in the world.[43][44] At the 2016 festival, representatives from Onagawa town performed, as a sign of appreciation for the support the town received from the Indian Government during the Great East Japan Earthquake.[45] The Indian National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) team had been dispatched in Onagawa for its first overseas mission and conducted search and rescue operations for missing people.[45]

Osamu Tezuka wrote a biographical manga Buddha from 1972 to 1983. On 10 April 2006, a Japanese delegation proposed to raise funds and provide other support for rebuilding the world-famous ancient Nalanda University, an ancient Buddhist centre of learning in Bihar, into a major international institution of education.[46]

Tamil movies are very popular in Japan and Rajnikanth is the most popular Indian star in this country.[47] Bollywood has become more popular among the Japanese people in recent decades,[48][49] and the Indian yogi and pacifist Dhalsim is one of the most popular characters in the Japanese video game series Street Fighter.

Starting 3 July 2014, Japan has been issuing multiple entry visas for the short term stay of Indian nationals.[50]

2016 nuclear deal

In November 2016, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on a three-day visit to Japan signed a deal with his counterpart Shinzo Abe on nuclear energy.[51] The deal took six years to negotiate, delayed in part by the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. This is the first time that Japan signed such deal with a non-signatory of Non-Proliferation Treaty. The deal gives Japan the right to supply nuclear reactors, fuel and technology to India. This deal aimed to help India build the six nuclear reactors in southern India, increasing nuclear energy capacity ten-fold by 2032.[52][53][54]

Development

In August 2017, the two countries announced the establishment of the Japan-India Coordination Forum (JICF) for Development of North-Eastern Region, described by India as "a coordination forum to identify priority development areas of cooperation for development" of northeast India. The forum will focus on strategic projects aimed at improving connectivity, roads, electric infrastructure, food processing, disaster management, and promoting organic farming and tourism in northeast India. A Japanese embassy spokesperson stated that the development of the northeast was a "priority" for India and its Act East Policy, and that Japan placed a "special emphasis on cooperation in North East for its geographical importance connecting India to South-East Asia and historical ties".[55] The forum held its first meeting on 3 August 2017.[56]

See also

References

- PM'S ADDRESS TO JOINT SESSION OF THE DIET, Indian Prime Minister's Office, 14 December 2006, retrieved 14 November 2009

- "2013 World Service Poll" (PDF), BBC

- "Butsuzōzui (Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images)" (digital photos) (in Japanese). Ehime University Library. 1796. p. (059.jpg).

- Chaudhuri, Saroj Kumar. Hindu Gods and Goddesses in Japan. (New Delhi, 2003) ISBN 81-7936-009-1.

- "Japan wants to encourage studies of Hindu gods" Satyen Mohapatra

- Bowring, Richard John (2005). The religious traditions of Japan, 500–1600. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-521-85119-0.

- Bowring, Richard John (2005). The religious traditions of Japan, 500–1600. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-521-85119-0.

- Dykstra, Yoshiko Kurata; De Bary, William Theodore (2001). Sources of Japanese tradition. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 100. ISBN 978-0-231-12138-5.

- Asia Society Buddhism in Japan, accessed July 2012

- "Japan-India Relations". Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- Leupp, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garten, Jeffrey (9 December 2006). "Really Old School". New York Times. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- Leupp, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leupp, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leupp, Gary P. (2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8264-6074-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "India-Japan relations". Embassy of India, Tokyo. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- "History of The Japan-India Association". japan-india.com. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Ambassador Ronen Sen's remarks at a luncheon meeting of the Japan Society in New York". indianembassy.org. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- Das, Subrata Kumar (2008-09-05). "Early light on the land of the rising sun". The Daily Star. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- "Ambassador's Message". in.emb-japan.go.jp. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Ian Sumner (2001). The Indian Army 1914–1947. Osprey Publishing. pp. 23–29. ISBN 9781841761961.

- Joyce C. Lebra, Jungle Alliance, Japan and the Indian National Army (1971) p 20

- Nayar, Mandira (15 February 2007). "India, Japan and world peace". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- Mathai, M.O. (1979). My Days with Nehru. Vikas Publishing House.

- "Nehru and Non-alignment". P.V. Narasimha Rao. Mainstream Weekly. 2 June 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- Mansingh, Lalit. "India-Japan Relations" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- "Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to be Republic Day chief guest". The Times of India. PTI. 6 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- Iain Marlow (3 September 2014). "India's Modi maintains warm ties with Japan's Abe". The Globe and Mail.

- Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury (2 September 2014). "India, Japan sign key agreements; to share 'Special Strategic Global Partnership'". Economic Times.

- "India, Japan sign landmark civil nuclear deal – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Roche, Elizabeth (11 November 2016). "India, Japan sign landmark civilian nuclear deal". Livemint. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- "Japan Plus". www.investindia.gov.in.

- "Japan PM Abe returns home after 'fruitful' India visit". newsbing.com. 21 December 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- Safi, Michael (2017-09-14). "India starts work on bullet train line with £12bn loan from Japan". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- Roy Choudhury, Srabani (October 2, 2017). "Shinzō Abe's India Visit: A Prologue". IndraStra Global. 003 (September (09)): 0013. ISSN 2381-3652.

- "India And Japan Sign Security Pact". IndiaServer. 23 October 2008. Archived from the original on 27 November 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- "Joint Declaration on Security Co-operation between Japan and India". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Ankit Panda (8 January 2014). "India-Japan Defense Ministers Agree To Expand Strategic Cooperation". The Diplomat. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Japan and India Bolster Trade and Defense Ties TIME

- David Brewster (2014-07-29). "Malabar 2014: a Good Beginning. Retrieved 13 August 2014".

- "Japan-India Friendship Year 2007". in.emb-japan.go.jp. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- "India, Japan committed to developing cultural ties". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 23 October 2007.

- "Namaste India Festival in Tokyo". ja.japantravel.com.

- "Namaste India 2016". indofestival.com.

- "Embassy of Japan in India". in.emb-japan.go.jp.

- Staff (2006-04-10). "Japan offer assistance in rebuiling Nalanda University". Oneindia. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- "Rajinikanth magic in Japan, yet again". Firstpost. 27 June 2012.

- Bollywood bigwigs hope Japan fans are in it for keeps Japan Times

- Japan: The fast emerging market for Bollywood films CNN-IBN

- "Japan to issue multiple entry visa to Indians for short stay". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. 3 July 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- Dipankan Bandopadhyay. "India and the Nukes". Politics Now. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "India, Japan Sign Landmark Nuclear Energy Deal After 6 Years Of Talks: 10 Points". NDTV. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "India, Japan sign landmark civil nuclear deal – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Bhattacherjee, Kallol, Kallol (11 November 2016). "Japan has option to scrap N-deal". The Hindu. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Bhaskar, Utpal (3 August 2017). "India, Japan join hands for big infrastructure push in Northeast". livemint.com/. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- "First meeting of Japan-India Coordination Forum (JICF) for Development of North-Eastern Region held". pib.nic.in. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

Further reading

- Eston, Elizabeth (2019). Rash Behari Bose: The Father of the Indian National Army, Vols 1-6. Tenraidou.

- An Indian freedom fighter in Japan: Memoirs of A.M. Nair (1982) Sole distributorship, Ashok Uma Publications ISBN 0-86131-339-9

- Lokesh Chandra (2014). Cultural interflow between India and Japan. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture

- Lokesh, C., & Sharada, R. (2002). Mudras in Japan. New Delhi: Vedams Books.

- Kak, Subhash. "The Vedic gods of Japan." Brahmavidyā: The Adyar Library Bulletin 68 (2004): 285.

- Green, Michael. Japan, India, and the Strategic Triangle with China Strategic Asia 2011–12: Asia Responds to Its Rising Powers – China and India (2011)

- Joshi, Sanjana. "The Geopolitical Context of Changing Japan-India Relations." UNISCI Discussion Papers 32 (2014): 117–136. online

- Chaudhuri, S. K. (2011). Sanskrit in China and Japan. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan.

- Naidu, G. V. C. "India and East Asia: The Look East Policy." Perceptions (2013)18#1 pp: 53–74. online

- Nakanishi, Hiroaki. "Japan-India civil nuclear energy cooperation: prospects and concerns." Journal of Risk Research (2014): 1–16. online

- Nakamura, H., & Wiener, P. P. (1968). Ways of thinking of Eastern peoples: India, China, Tibet, Japan. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii.

- Thakur, Upendra. "India and Japan, a Study in Interaction During 5th Cent.-14th Cent. A.D." "Abhinav Publications"

- De, B. W. T. (2011). The Buddhist tradition in India, China & Japan. New York: Vintage eBooks.

- Van, G. R. H. (2001). Siddham: An essay on the history of Sanskrit studies in China and Japan. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan.

External links

- Japan-India Relations Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- Research, Reference and Training Division (2008). India 2008 (PDF). New Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. ISBN 978-81-230-1488-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-03. Retrieved 2013-09-11.