1990 Luzon earthquake

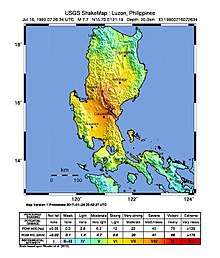

The 1990 Luzon earthquake struck the island of Luzon in the Philippines at 4:26 p.m. on July 16 (PDT). 3:26 p.m. (PST) with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.7 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent) and produced a 125 km-long ground rupture that stretched from Dingalan, Aurora to Cuyapo, Nueva Ecija. The event was a result of strike-slip movements along the Philippine Fault and the Digdig Fault within the Philippine Fault System. The earthquake's epicenter was near the town of Rizal, Nueva Ecija, northeast of Cabanatuan City.[4] An estimated 1,621 people were killed,[5][6] most of the fatalities located in Central Luzon and the Cordillera region.

| UTC time | 1990-07-16 07:26:36 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 362868 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | July 16, 1990 |

| Local time | 16:26 local time |

| Duration | 45 seconds |

| Magnitude | 7.7 Mw[1] |

| Depth | 25.1 km (15.6 mi)[1] |

| Epicenter | 15.679°N 121.172°E[1] |

| Type | Strike-slip[2] |

| Areas affected | Central Luzon National Capital Region Cordillera Administrative Region Bicol Region Philippines |

| Max. intensity | IX (Violent)[3] |

| Tsunami | eastern seaboard of Luzon |

| Casualties | 1,621 |

Impact

The earthquake caused damage within an area of about 20,000 square kilometers, stretching from the mountains of the Cordillera Administrative Region and through the Central Luzon region. The earthquake was strongly felt in Metropolitan Manila, destroying many buildings and leading to panic and stampedes and ultimately three deaths in the National Capital Region,[10] one of the lowest fatalities recorded in the wake of the tremor. The Southern Tagalog (nowadays Regions 4A and 4B) and Bicol Regions also felt the quake, but with low casualty figures.

Baguio City

The popular tourist destination of Baguio, situated over 5000 feet above sea level, was among the areas hardest hit by the Luzon earthquake. The earthquake caused 28 collapsed buildings, including hotels, factories, and government and university buildings, as well as many private homes and establishments.[11] The quake destroyed electric, water and communication lines in the city.[12] The main vehicular route to Baguio, Kennon Road, as well as other access routes to the mountain city, were shut down due to landslides and it took three days before enough landslide debris was cleared to allow access by road to the stricken city.[12]

Baguio City was isolated from the rest of the Philippines for the first 48 hours after the quake. Damage at Loakan Airport rendered access to the city by air limited to helicopters.[12] American and Philippine Air Force C-130s evacuated many residents from this airport. Many city residents, as well as patients confined in hospital buildings damaged by the quake, were forced to stay inside tents set up in public places, such as in Burnham Park and in the streets. Looting of department stores in the city was reported.[13] Among the first rescuers to arrive at the devastated city were miners from Benguet Corporation, who focused on rescue efforts at the collapsed Hotel Nevada.[14] Teams sent by the Philippine government and by foreign governments and agencies likewise participated in the rescue and retrieval operations in Baguio City.

One of the more prominent buildings destroyed was the Hyatt Terraces Baguio Hotel, where at least eighty hotel employees and guests were killed. However, three hotel employees were pulled out alive after having been buried under the rubble for nearly two weeks, and after international rescue teams had abandoned the site convinced there were no more survivors.[15] Luisa Mallorca and Arnel Calabia were extricated from the rubble 11 days after the quake, while hotel cook Pedrito Dy was recovered alive 14 days following the earthquake.[16] All three survived in part by drinking their own urine[16] and in Dy's case, rainwater.[14] At that time, Dy's 14-day ordeal was cited as a world record for entombment underneath rubble.[15]

The United States Agency for International Development was sponsoring a seminar at the Hotel Nevada when the tremor struck, causing the hotel to collapse. 27 of the seminar participants, including one American USAID official, were killed in the quake.[11] Among those who were pulled out alive from the ruins of the hotel was future senatorial candidate Sonia Roco, wife of politician Raul Roco, who was pulled out from the rubble by miners after 36 hours.[17]

Cabanatuan City

In Cabanatuan City, Nueva Ecija, the tallest building in the city, a six-story concrete school building housing the Christian College of the Philippines, collapsed during the earthquake, which occurred during school hours. Around 154 people were killed at the CCP building. Unlike in Baguio City, local and international journalists were able to arrive at Cabanatuan City within hours after the tremor, and media coverage of the quake in its immediate aftermath centered on the collapsed school, where rescue efforts were hampered by the lack of heavy equipment to cut through the steel reinforcement of fallen concrete.[10] Some of the victims who did not die in the collapse were found dead later from dehydration because they were not pulled out in time.[18]

A 20-year-old high school student, Robin Garcia, was later credited with rescuing at least eight students and teachers by twice returning under the rubble to retrieve survivors. Garcia was killed by an aftershock hours after the quake while trying to rescue more survivors, and he received several posthumous tributes, including medals of honor from the Boy Scouts of the Philippines and President Corazon Aquino's[19] Grieving Heart Award for his heroic effort that brought the world's attention to the quake due to quick media coverage in the city, since most of the buildings were damaged save for the CCP building which was collapsed totally.

Dagupan City

In Dagupan City, about 90 buildings in the city were damaged, and about 20 collapsed. Some structures sustained damage because liquefaction caused buildings to sink as much as 1 metre (39 inches). The earthquake caused a decrease in the elevation of the city and several areas were flooded. The city suffered 64 casualties of which 47 survived and 17 died. Most injuries were sustained during stampedes at a university building and a theater.

La Union

Five municipalities in La Union were affected: Agoo, Aringay, Caba, Santo Tomas, and Tubao with a combined population of 132,208. Many buildings, including the Agoo Municipal hall,[20] the Museo de Iloko and the Basilica Minore of our Lady of Charity,[21] collapsed or were severely damaged. 100,000 families were displaced when two coastal villages sank due to liquefaction. The province suffered many casualties leaving 32 people dead.

Patterns of damage

Based on preliminary analysis, cases and controls were similar in age and sex distribution. Similar proportions of cases and controls were inside buildings (74% and 80%, respectively) and outside buildings (26% and 20%, respectively) during the earthquake. For persons who were inside a building, risk factors included building height, type of building material, and the floor level the person was on. Persons inside buildings with seven or more floors were 35 times more likely to be injured. Persons inside buildings constructed of concrete or mixed materials were three times more likely to sustain injuries than were those inside wooden buildings. Persons at middle levels of multistory buildings were twice as likely to be injured as those at the top or bottom levels.

The earthquake caused different patterns of damage in different parts of Luzon Island. The mountain resort of Baguio was most severely affected, it had a high population density and many tall concrete buildings, which were more susceptible to seismic damage. Relief efforts proved difficult as all routes of communication, roads, and airport access were severed for several days following the quake. These efforts were further hampered by daily rainfall. Baguio is home to a large mining company and a military academy; experienced miners and other disciplined volunteers played a crucial role in early rescue efforts. Rescue teams arriving from Manila and elsewhere in Luzon were able to decrease mortality from major injuries. Surgeons, anesthesiologists, and specialized equipment and supplies were brought to the area, and victims were promptly treated. Patients requiring specialized care (e.g., hemodialysis) not available in the disaster area were airlifted to tertiary hospitals. Damage was caused by landslides in the mountains and settling in coastal areas. Relief efforts in these areas were prompt and successful, partly because those areas remained accessible.

On July 19, three days after the earthquake, the priority of relief efforts shifted from treatment of injuries to public health concerns. For example, numerous broken pipes completely disrupted water systems, limiting the availability of potable water, and refugees who camped in open areas had no adequate toilet facilities. Early efforts at providing potable water by giving refugees chlorine granules were unsuccessful. Most potable water was distributed from fire engines, and Department of Health (DOH) sanitarians chlorinated the water before it was distributed. Surveys of refugee areas showed few latrines; these had to be dug by the DOH.[22]

In popular culture

The earthquake is featured in the documentary series Earth's Fury in an episode entitled "Earthquake!" and The Amazing Video Collection: Natural Disasters.

See also

Bibliography

- Rantucci, Giovanni (1980). Geological Disasters In The Philippines: The July 1990 Earthquake And The June 1991 Eruption of Mount Pinatubo. Description, effects and lessons learned. Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS). ISBN 978-0-7881-2075-6. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

References

- "M 7.7 - Luzon, Philippines". United States Geological Survey. July 16, 1990. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- USGS (September 4, 2009), PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey, archived from the original on January 15, 2018, retrieved October 24, 2018

- National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS) (1972), Significant Earthquake Database (Data Set), National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K, archived from the original on July 21, 2017, retrieved March 11, 2016

- "The July 16 Luzon Earthquake: A Technical Monograph". Inter-Agency Committee for Documenting and Establishing Database on the July 1990 Earthquake. Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. 2001. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- The World Almanac and Book of Facts 2008: 140th Anniversary Edition. United States: World Almanac Education Group Inc. 2008. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-60057-072-8.

- John W. Wright, ed. (2008). The New York Times 2008 Almanac. United States: Penguin Group. pp. 753. ISBN 978-0-14-311233-4.

- "M 7.4 - Luzon, Philippines". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "M 7.0 - Luzon, Philippines". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "M 7.0 - Luzon, Philippines". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "Earthquake in the Philippines Kills at Least 260, Including 50 Children in One School". The New York Times. July 17, 1990. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- "Manila Assesses Damage and High Cost of Quake". The New York Times. July 20, 1990. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- "International notes Earthquake Disaster – Luzon, Philippines". Center for Disease Control. August 31, 1990. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- Jomar Kho Indanan (August 22, 1990). "The Worst of Times". National Midweek. p. 46.

- Moulic, Gobleth (December 10, 2004). "How Baguio quake victim survived 15-day ordeal under rubble". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- "Quake Update". National Midweek. August 22, 1990. p. 39.

- "A 3rd Survivor Pulled From Collapsed Hotel". Deseret News. July 30, 1990. Archived from the original on April 12, 2009. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- Norman Bordadora & Michael Lim Ubac (April 17, 2007). "Roco trapped in elevator on Friday the 13th". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- "Earthquake Wreaks Havoc in the Philippines". This Day in History. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- Guingona, Teofisto (1993). The Gallant Filipino. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing Inc. pp. 211–213. ISBN 978-971-27-0279-2.

- "23 Years in La Union". The Philippine Navigators. December 12, 2015. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Sals, Florent Joseph (2005). The History of Agoo: 1578-2005. La Union: Limbagan Printhouse. p. 80.

- "International notes Earthquake Disaster – Luzon, Philippines". Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

External links

- EIRD overview

- The 1990 Baguio City Earthquake (Archived 2009-10-21)

- International notes Earthquake Disaster – Luzon, Philippines

- Rapid.Org.UK – Philippines earthquake

- Steven Erlanger (July 19, 1990). "Hopes Dying In the Rubble In Philippines". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)