Japan–United Kingdom relations

Japan–United Kingdom relations (日英関係, Nichieikankei) are the bilateral and diplomatic relations between Japan and the United Kingdom.

| |

Japan |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Japan, London | British Embassy, Tokyo |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Koji Tsuruoka | Ambassador Paul Madden |

History

The history of the relationship between Japan and England began in 1600 with the arrival of William Adams (Adams the Pilot, Miura Anjin) on the shores of Kyushu at Usuki in Ōita Prefecture. During the Sakoku period (1641–1853), there were no formal relations between the two countries. The Dutch served as intermediaries. The treaty of 1854 began formal diplomatic ties, which improved to become a formal alliance 1902–1922. The British Dominions pressured Britain to end the alliance. Relations deteriorated rapidly in the 1930s, over the Japanese invasions of Manchuria and China, and the cutoff of oil supplies in 1941. Japan declared war in December 1941 and seized Hong Kong, British Borneo (with its oil), and Malaya. They sank much of the British fleet and forced the surrender of Singapore, with many prisoners. They reached the outskirts of India until being pushed back. Relations improved in the 1950s and, as memories of the wartime atrocities fade, have become warm. On 3 May 2011, British Foreign Secretary William Hague said that Japan is "one of [Britain]'s closest partners in Asia".

Chronology of Japanese–British relations

- 1577. Richard Wylles writes about the people, customs and manners of Giapan in the History of Travel published in London.

- 1580. Richard Hakluyt advises the first English merchants to find a new trade route via the Northwest passage to trade wool and silver with Japan (sending two ships, the George and William, returning unsuccessfully by Christmas the same year). [1]

- 1587. Two young Japanese men named Christopher and Cosmas sailed on a Spanish galleon to California, where their ship was seized by Thomas Cavendish. Cavendish brought the two Japanese men with him to England where they spent approximately three years before going again with him on his last expedition to the South Atlantic where they were heading to Japan to begin trade relations. They are the first known Japanese men to have set foot in the British Isles.[2]

Early

- 1600. William Adams, a seaman from Gillingham, Kent, was the first English adventurer to arrive in Japan. Acting as an advisor to the Tokugawa shōgun, he was renamed Miura Anjin, granted a house and land, and spent the rest of his life in his adopted country. He also became one of the first known foreign Samurai.

- 1605. John Davis, the famous English explorer, was killed by Japanese pirates off the coast of Thailand, thus becoming the first known Englishman to be killed by a Japanese.[3]

- 1613. Following an invitation from William Adams in Japan, the English captain John Saris arrived at Hirado Island in the ship Clove with the intent of establishing a trading factory. Adams and Saris travelled to Suruga Province where they met with Tokugawa Ieyasu at his principal residence in September before moving on to Edo where they met Ieyasu's son Hidetada. During that meeting, Hidetada gave Saris two varnished suits of armour for King James I, today housed in the Tower of London.[4] On their way back, they visited Tokugawa once more, who conferred trading privileges on the English through a Red Seal permit giving them "free licence to abide, buy, sell and barter" in Japan.[5] The English party headed back to Hirado Island on 9 October 1613. However, during the ten-year activity of the company between 1613 and 1623, apart from the first ship (Clove in 1613), only three other English ships brought cargoes directly from London to Japan.

- 1623. The Amboyna massacre occurred. After the incident England closed its commercial base at Hirado Island, now in Nagasaki Prefecture, without notifying Japan. After this, the relationship ended for more than two centuries.

- 1639. Tokugawa Iemitsu announced his Sakoku policy. Only the Netherlands was permitted to retain limited trade rights.

- 1640. Ureamon Eaton the son of William Eaton (a worker at the EIC post in Japan) and Kamezo (a Japanese woman), becomes the first Japanese to join Academia in England as a scholar at Trinity College Cambridge.

- 1673. An English ship named "Returner" visited Nagasaki harbour, and asked for a renewal of trading relations. But the Edo shogunate refused. The government blamed it on the withdrawal 50 years earlier, and found it unacceptable that Charles II of England married Catherine of Braganza, who was from Portugal, and favoured the Roman Catholic Church.

- 1808. The Nagasaki Harbour Incident: HMS Phaeton enters Nagasaki to attack Dutch shipping.

- 1832. Otokichi, Kyukichi and Iwakichi, castaways from Aichi Prefecture, crossed the Pacific and were shipwrecked on the west coast of North America. The three Japanese men became famous in the Pacific Northwest and probably inspired Ranald MacDonald to go to Japan. They joined a trading ship to the UK, and later Macau. One of them, Otokichi, took British citizenship and adopted the name John Matthew Ottoson. He later made two visits to Japan as an interpreter for the Royal Navy.

1854–1900

- 1854. 14 October. The first limited Anglo-Japanese Friendship Treaty was signed by Admiral Sir James Stirling and representatives of the Tokugawa shogunate (Bakufu).

- 1855. In an effort to find the Russian fleet in the Pacific Ocean during the Crimean war, a French-British naval force reached the port of Hakodate, which was open to British ships as a result of the Friendship Treaty of 1854, and sailed further north, seizing the Russian-American Company's possessions on the island of Urup in the Kuril archipelago. The Treaty of Paris (1856) restitutes the island to Russia.[6]

- 1858. 26 August. The Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce was signed by the Scot Lord Elgin and representatives of the Tokugawa shogunate for Japan, after the Harris Treaty was concluded. Britain obtained extraterritorial rights on Japanese with the British Supreme Court for China and Japan, in Shanghai. A British iron paddle schooner named Enpiroru was presented to the Tokugawa administration by Bruce as a present for the Emperor from Queen Victoria.

- 1861. 5 July. The British legation in Edo was attacked.

- 1862. The shōgun sends the First Japanese Embassy to Europe, led by Takenouchi Yasunori.

- 1862. 14 September. The Namamugi Incident occurred within a week of the arrival of Ernest Satow in Japan.

- 1862–75. British Military Garrison established at Yamate, Yokohama.

- 1863. The Chōshū Five began their education at University College London under the guidance of Professor Alexander William Williamson.

- 1863. Bombardment of Kagoshima by the Royal Navy. (Anglo-Satsuma War).

- 1864. Bombardment of Shimonoseki by Britain, France, the Netherlands and the USA.

- 1865. The Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (HSBC) from Britain was established in Hong Kong.

- 1865. Chōshū Domain bought the warship Union from Glover and Co., an agency of Jardine Matheson established in Nagasaki, in the name of Satsuma Domain which was not against the Tokugawa shogunate then.

- 1866 HSBC established a Japanese branch in Yokohama.

- 1867. The Icarus affair, an incident involving the murder of two British sailors in Nagasaki, leading to increased diplomatic tensions between Britain and the Tokugawa shogunate.

- 1868. Coup d'état by Chōshū Domain and Satsuma Domain achieved the Meiji Restoration.

- 1869. Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh becomes the first European prince to visit Japan arriving on HMS Galatea on 4 September 1869. Audience with the Emperor Meiji in Tokyo.

- 1872. The Iwakura mission visited Britain as part of a diplomatic and investigative tour of the United States and Europe.

- 1873. The Imperial College of Engineering opened with Henry Dyer as principal.

- 1879 British Court for Japan was established in Yokohama.

- 1880. Japan government established Yokohama Specie Bank for only foreign transaction bank in Japan, with the support of HSBC.

- 1886. Normanton incident British merchant vessel sinks off the coast of Wakayama Prefecture. Crew escape while 25 Japanese passengers perish. Widespread Japanese public outrage as subsequent Board of Enquiry under extraterritorial court fails to hold British crew to account.

- 1885–87. Japanese exhibition at Knightsbridge, London.[7]

- 1887–89. Jurist Francis Taylor Piggott, the son of ex-MP Jasper Wilson Johns, was inaugurated as a legislational consultant for Itō Hirobumi, then and the first Prime Minister of Japan.

- 1890. Government of Japan established the Constitution of Imperial Japan which House of Peers was not come with Universal suffrage.

- 1891. The Japan Society of London is founded by Arthur Diosy.

- 1894. The Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation was signed in London on 16 July. The treaty abolished extraterritoriality in Japan for British subjects with effect from 17 July 1899

- 1899. Extraterritorial rights for British subjects in Japan came to an end.

- 1900. (January). Last sitting of the British Court for Japan.

20th century

- 1902. The Japanese–British alliance was signed in London on 30 January. It was a diplomatic milestone that saw an end to Britain's splendid isolation, and removed the need for Britain to build up its navy in the Pacific.[8][9]

- 1905. The Japanese–British alliance was renewed and expanded. Official diplomatic relations were upgraded, with ambassadors being exchanged for the first time.

- 1907. In July, British thread company J. & P. Coats launched Teikoku Seishi and began to thrive.

- 1908. The Japan-British Society was founded in order to foster cultural and social understanding.

- 1909 Fushimi Sadanaru returns to Britain to convey the thanks of the Japanese government for British advice and assistance during the Russo-Japanese War.

- 1910. Sadanaru represents Japan at the state funeral of Edward VII, and meets the new king George V at Buckingham Palace.

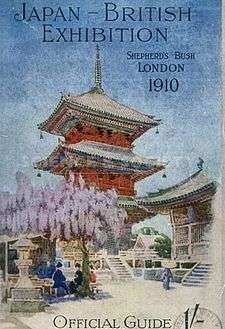

- 1910. The Japan–British Exhibition is held at Shepherd's Bush in London. Japan made a successful effort to display its new status as a great power by emphasizing its new role as a colonial power in Asia. [10]

- 1911. The Japanese – British alliance was renewed with approval of the dominions.

- 1913. The IJN Kongō, the last of the British-built warships for Japan's navy, enters service.

- 1914–1915. Japan joined World War I as Britain's ally under the terms of the alliance and captured German-occupied Tsingtao (Qingdao) in China Mainland. They also help Australia and New Zealand capture archipelagos like the Marshall Islands and the Mariana Islands.

- 1915. The Twenty-One Demands would have given Japan varying degrees of control over all of China, and would have prohibited European powers from extending their Chinese operations any further.[11]

- 1917. The Imperial Japanese Navy helps the Royal Navy and allied navies patrol the Mediterranean against Central Powers ships.

- 1917-1935. Close relationships between the two country steadily worsens. [12]

- 1919. Japan proposes a racial equality clause in negotiations to form the League of Nations, calling for "making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality."[13] Britain, which supports the White Australia policy, cannot assent, and the proposal is rejected.

- 1921. Britain indicates it will not renew the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 primarily because of opposition from the United States and also Canada.[14]

- 1921. Crown Prince Hirohito visited Britain and other Western European countries. It was the first time that a Japanese crown prince had traveled overseas.

- 1921. Arrival in September of the Sempill Mission in Japan, a British technical mission for the development of Japanese Aero-naval forces. It provided the Japanese with flying lessons and advice on building aircraft carriers; the British aviation experts kept close watch on Japan after that. [15]

- 1922. Washington Naval Conference concluding in the Four-Power Treaty, Five-Power Treaty, and Nine-Power Treaty; major naval disarmament for 10 years with sharp reduction of Royal Navy & Imperial Navy. The Treaties specify that the relative naval strengths of the major powers are to be UK = 5, US = 5, Japan = 3, France = 1.75, Italy = 1.75. The powers will abide by the treaty for ten years, then begin a naval arms race.[16]

- 1922. Edward, Prince of Wales travelling on HMS Renown, arrives in Yokohama on 12 April for a four-week official visit to Japan.

- 1923. The Japanese -British alliance was officially discontinued on 17 August in response to U.S. and Canadian pressure.

- 1930. The London disarmament conference angers Japanese Army and Navy. Japan's navy demanded parity with the United States and Britain, but was rejected; it maintained the existing ratios and Japan was required to scrap a capital ship. Extremists assassinate Japan's prime minister, and the military takes more power.[17]

- 1931. September. Japanese Army seizes control of Manchuria, which China has not controlled in decades. It sets up a puppet government. Britain and France effectively control the League of Nations, which issues the Lytton Report in 1932, saying that Japan had genuine grievances, but it acted illegally in seizing the entire province. Japan quits the League, Britain takes no action.[18][19]

- 1934. The Royal Navy sends ships to Tokyo to take part in a naval parade in honour of the late Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, one of Japan's greatest naval heroes, the "Nelson of the East".

- 1937. The Kamikaze, a prototype of the Mitsubishi Ki-15, travels from Tokyo to London, the first Japanese-built aircraft to land in Europe, for the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

- 1938 Yokohama Specie Bank acquired HSBC.[20]

- 1939. The Tientsin Incident almost causes an Anglo-Japanese war when the Japanese blockade the British concession in Tientsin, China.

World War II

- 1941. 7/8 December. Pacific War begins as the Japan attacks British colonial possessions in the Far East.

- 1941–42. In the first few months of war Japanese forces race from victory to victory. They capture Hong Kong, British Borneo, Malaya, Singapore and Burma.

- The surrender of Singapore is a humiliating defeat for the British; over hundred thousand Imperial soldiers become prisoners. Japanese nationalists celebrate the victory over the Europeans.[21] Many British POWs die in very harsh conditions of captivity.

- 1944. The Japanese invasion of India via Burma ends in disaster. The resulting battles of Imphal and Kohima becomes the worst defeat on land to that date in Japanese history.[22]

- 1945. August. The last significant land battle of the Second World War involved British and Japanese forces. It took place in Burma – a failed Japanese breakout attempt in the Pegu Yomas.

- 1945. 2 September. Aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Admiral Bruce Fraser is among the allied commanders formally accepting the surrender of Japan.

- 1945–46. British troops use Japanese prisoners of war to quell nationalist uprisings in both recently liberated French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies. A battalion commander Major Kido is even recommended by General Philip Christison for a DSO.

Post War

- 1945–1951. Japan is under allied occupation. The British Commonwealth Force occupy the western prefectures of Shimane, Yamaguchi, Tottori, Okayama and Hiroshima and the territory of Shikoku Island. In 1951, this becomes British British Commonwealth Forces Korea with the commencement of the Korean war.

- 1948. The 1948 Summer Olympics was held in London. Japan did not participate.

- 1951. Treaty of San Francisco – the peace treaty in which Anglo-Japanese relations were normalized. Japan's accepted the judgements of the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal. According to Peter Lowe, the British were still angry over the humiliation of the surrender of Singapore in 1942; resentment at American domination of the occupation of Japan; apprehension concerning renewed Japanese competition in textiles and shipbuilding; and bitterness regarding the atrocities against prisoners of war. [23]

- 1953. Nineteen-year-old Crown Prince Akihito (Emperor from 1989 to 2019), represents Japan at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

- 1953. The British Council in Japan was established.

- 1957. Japanese Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi decided to compensate the government of France and Banque de l'Indochine in pound sterling.[24]

- 1963. The University of Oxford set Japanese as a subject in its Oriental Institute (the Sub-Faculty of East Asian Studies).

- 1966. The Beatles played at Nippon Budokan in Tokyo to overwhelming adulation. This performance emphasized growing good will between Britain and Japan in their foreign relations policies.

- 1971. HIM Emperor Hirohito pays a state visit to the United Kingdom after an interval of 50 years.[25]

- 1975. Queen Elizabeth II pays a state visit to Japan.[26]

- 1978. Beginning of the BET scheme (British Exchange Teaching Programme) first advocated by Nicholas MacLean.[27]

- 1980s The British-Japanese Parliamentary Group was established in Britain in early 1980s.[28]

- 1983. Naruhito (now Emperor of Japan) studied at Merton College, Oxford, until 1985, and researched transport on the River Thames.

- 1986. Nissan Motors began to operate its car plant in Sunderland, as Nissan Motor Manufacturing (UK) Ltd.

- 1986. The Prince and Princess of Wales conducted a successful royal visit.

- 1987. JET (Japan Exchange and Teaching) program starts when the BET scheme and the Fulbright scholarship are merged.

- 1988. The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation established.

- 1990. The Alumni Association for British JET Participants JETAA UK is established

- 1991. The first Sumo tournament to be held outside Japan is hosted at the Royal Albert Hall in London.[29]

- 1998. Emperor Akihito pays a state visit to the United Kingdom.[25][30]

21st century

- 2001. The year-long "Japan 2001" cultural-exchange project saw a major series of Japanese cultural, educational and sporting events held around the UK.

- 2001. JR West gifts a 0 Series Shinkansen (No. 22-141) to the National Railway Museum at York, she is the only one of her type to be preserved outside Japan.

- 2007. HIM Emperor Akihito pays his second state visit to the United Kingdom.

- 2011. UK sends over rescue men with rescue dogs and supplies to help the Japanese, after the 11 March 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami.

- 2012. A UK trade delegation to Japan, led by Prime Minister David Cameron, announces an agreement to jointly develop weapons systems.

- February 2015. Prince William, Duke of Cambridge on an official visit tours areas devastated by the 2011 Tsunami including Fukushima, Ishinomaki, and Onagawa.[31]

- September 2016. Citing concerns for Japanese owned business operating in the United Kingdom in the wake of the European Union membership referendum, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs directly issues a 15-page memorandum on its own website requesting that the British Government strike a Brexit agreement safeguarding UK's current trading rights in the European Single Market.[32]

- December 2018. A new trade deal between Japan and the European Union which is hoped could also act as blue-print for post-Brexit trade between Japan and the UK was approved by the European Parliament.[33]

See also the chronology on the website of British Embassy, Tokyo.[34]

Britons in Japan

- William Adams (Miura Anjin) - Hatamoto & Advisor to the Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu

- Arthur Adams - Zoologist who studied Japanese sealife onboard the HMS Samarang in 1845

- Rutherford Alcock - British Diplomat to Japan from 1858 - 1864 and the first 'outsider' to climb Mount Fuji in 1860

- William Anderson - A prominent collector who donated to the British Museum

- William George Aston - Consular official and Japanologist

- Matilda Chaplin Ayrton - Scholar and founder of a Midwife Hospital between 1873 - 1875 in Japan

- William Edward Ayrton - Professor of Physics & Telegraphy at the Imperial College of Engineering, introduced the Arc Lamp to Japan in 1878

- Michael Buckworth Bailey - First Anglican consular staff from 1862 - 1874

- Thomas Baty - Legal advisor to the Japanese Empire

- John Batchelor - Anglican Missionary specialist on the Ainu

- Felice Beato - British/Italian/Corfiote Photographer

- Edward Bickersteth - First Anglican Bishop of South Tokyo

- Isabella Bird - Victorian Traveller and Author

- John Reddie Black - Publisher of newspapers, principally The Far East

- Carmen Blacker - English Japanologist Cambridge lecturer

- Thomas Blakiston - English Naturalist noted for Blakiston's Line and Blakiston's Fish Owl

- Reginald Horace Blyth - Helped to introduce Zen and Haiku to the West during WWII into the 1950s, one of his students being Alan Watts

- Alan Booth - Author of The Roads to Sata and a Noh enthusiast

- Duncan Gordon Boyes - Winner of the Victoria Cross at Shimonoseki, 1864

- William Robert Broughton - Surveyed Eastern Honshu and Hokkaido in the HMS Providence (1791) between 1795 - 1798

- Richard Henry Brunton - Father of Japanese Lighthouses

- Basil Hall Chamberlain - Translator and Prominent Japanologist

- Edward Bramwell Clarke - Professor who helped introduce rugby to Japan

- Richard Cocks - Head Merchant of the first British venture in Hirado from 1613 - 1623

- Samuel Cocking - Yokohama Merchant

- Josiah Conder - Architect known for the Rokumeikan, his books on Japanese gardening and being a pupil of Kawanabe Kyosai

- Hugh Cortazzi - Japanologist and former Ambassador

- James Main Dixon, former FRSE - Scottish Professor who taught Natsume Soseki

- William Gray Dixon - see Land of the Morning

- Archibald Douglas - Foreign Advisor to the Imperial Japanese Navy, introduced football to Japanese Naval Cadets

- Christopher Dresser - Designer and major influence on the Anglo-Japanese style & Writer on Japan

- Henry Dyer - First principal of the Imperial College of Engineering (Kobu Daigakko)

- Alfred East - English watercolour artist commissioned by the Fine Art Society to paint scenes in Japan in 1889

- Lord Elgin - Signatory to the British 'unequal' treaty of 1858

- James Alfred Ewing - Scottish Professor

- Henry Faulds - Scottish doctor who founded a hospital in Tsukiji which became the basis for St. Luke's International Hospital and helped introduce Joseph Lister's antiseptic methods to Japanese Surgeons

- Hugh Fraser - British minister 1889–94

- Mary Crawford Fraser - see Diplomatist's Wife in Japan

- Thomas Blake Glover - Scottish trader who was key to the industrialisation of Meiji Japan, smuggled over the Choshu Five to Britain

- Abel Gower - Consul

- William Gowland - Father of Japanese Archaeology

- Thomas Lomar Gray - Engineering Professor and Seismologist

- Arthur Hasketh Groom - Creator of the first golf course in Japan

- John Harington Gubbins - Diplomat to the Empire of Japan

- Nicholas John Hannen - British barrister for the British Supreme Court for China and Japan from 1871–1900 in varying roles

- Edward Atkinson Hornel - Scottish Artist influenced by Japanese design who visited from 1893–1894

- Collingwood Ingram - known as "Cherry Ingram", a specialist cherry tree collector

- Grace James - Japanese folklorist and childrens Writer

- Cargill Gilston Knott - Scottish Physicist whose work in seismology led to the first earthquake hazard survey of Japan

- Frank Toovey Lake – Young sailor who died aged 19 interred in Sanuki Hiroshima whose grave has been up-kept since 1868

- Bernard Leach - An influential Potter whose formative years were spent in Japan

- Mary Cornwall Legh - Anglican Missionary who worked with those with Leprosy

- John Liggins - Anglican Missionary who landed in 1859

- Arthur Lloyd - Anglican missionary notable for his work on Mahayana Buddhism

- Joseph Henry Longford - Consul and Academic

- Claude Maxwell MacDonald - Diplomat

- Ranald MacDonald - The first native English teacher in Japan

- Charles Maries - English botanist sent by Veitch Nurseries who collected in Japan from 1877 - 1879

- John Milne - Professor and Father of Seismology

- Algernon Bertram Mitford (Lord Redesdale) - Diplomat & Author of Tales of Old Japan

- Edmund Morel – 'the father of Japanese railways', a foreign Advisor to the Meiji government on railways

- James Murdoch - Wrote the first academic history of Japan in English

- Edward St. John Neale, Lt.-Col, Secretary of Legation then Chargé d'Affaires 1862–1863

- Mary Clarke Nind, Methodist missionary who toured Japan in May 1894

- Marianne North, Victorian Traveller and Botany painter who visited in 1875

- Laurence Oliphant – Secretary of the Legation in 1861

- Yei Theodora Ozaki - A 20th-century translator of Japanese fairy tales for children in English

- Henry Spencer Palmer - Foreign Advisor on Civil Engineering for the Yokohama area and The Times correspondent

- Harry Smith Parkes - Diplomat during Boshin War

- Alfred Parsons - Visited and wrote of Japan from 1892 – 1895 in "Notes in Japan"

- John Perry - Colleague of Ayrton at the Imperial College of Engineering, Tokyo

- Charles Lennox Richardson - slain in the Namamugi Incident

- Hannah Riddell - Opened the first leprosy research laboratory in Japan in 1918

- Frederick Ringer - Industrialist and Nagasaki Businessman

- George Bailey Sansom - Japanologist of the early 20th century

- Ernest Mason Satow - Notable Diplomat and Japanologist

- Timon Screech - SOAS Professor of Arts

- Alexander Cameron Sim - founder of Kobe Regatta & Athletic Club, introduced lemonade (Ramune) to Japan.

- Admiral Sir James Stirling – Signatory to the 1854 treaty

- Walter Weston - Rev. who publicised the term "Japanese Alps"

- William Willis - Doctor

- Channing Moore Williams - Founder of Rikkyo University, he also helped to set up the Anglican Church in Japan

- Ernest Henry Wilson - Plant Collector who brought 63 sakura to the West from 1911 - 1916, the Wilson stump (ウィルソン株, Wilson kabu) also has his namesake

- Charles Wirgman - Editor of Japan Punch

The chronological list of Heads of the United Kingdom Mission in Japan.

Japanese in the United Kingdom

(see article Japanese in the United Kingdom).

The family name is given in italics. Usually the family name comes first in regards to Japanese historical figures, but in modern times not so for the likes of Kazuo Ishiguro and Katsuhiko Oku, both well known in the United Kingdom.

- Yuki Amami - Actress - studied in England

- Aoki Shuzo - Diplomat, signed the 1894 treaty in London

- Genda Minoru - Naval attaché and planner of the Pearl Harbor strike; in 1940 he saw Spitfires and Bf 109s in combat over London during the Battle of Britain

- Hayashi Tadasu - A student in London from 1866 - 1868

- Yuzuru Hiraga - IJN naval officer who was educated at London from 1905 - 1908, part of the design team for the famous Yamato battleship

- Taka Hirose - Bassist of the band Feeder

- Inagaki Manjirō - Cambridge University graduate and diplomat

- Imekanu - Ainu Yukar poet who worked with John Batchelor

- Kazuo Ishiguro - Famous Writer, see The Remains of the Day

- Iwakura Tomomi - see Iwakura mission especially

- Shinji Kagawa - played for English football club Manchester United

- Kamisaka Sekka - Studied and spread Japonisme and Art Nouveau, studied in Glasgow from 1901 - 1910

- Kikuchi Dairoku - Cambridge University graduate and politician

- Kunisawa Shinkurō - Yōga painter who studied in England in the Meiji era

- Yoshio Markino - Japanese Artist active in London in the first half of the 20th century

- Mori Arinori - Studied at University College London in 1865 one of the Satsuma students

- Naoko Mori - Actress - famous for playing Toshiko Sato in Torchwood and Doctor Who

- Yoshinori Muto - Footballer for Newcastle United

- Shunsuke Nakamura - played for Scottish football club Celtic

- Natsume Sōseki - Author of I Am a Cat

- Shinji Okazaki - footballer for Leicester City

- Katsuhiko Oku - Oxford University rugby player, diplomat in Japanese embassy in London who died in Iraq, 2003. Posthumously promoted to ambassador. See also the Oku-Inoue fund for the children of Iraq.

- Kishichiro Okura - 20th century Entrepreneur

- Hisashi Owada - Cambridge University graduate, father of Princess Masako

- Rina Sawayama - 21st century Musician

- Suematsu Kenchō - Cambridge University graduate and statesman

- Ginnosuke Tanaka - Cambridge University graduate, introduced rugby to Japan

- Tōgō Heihachirō - Spent time in the UK, one of Japan's greatest naval heroes, the "Nelson of the East"

- Maya Yoshida - footballer currently playing for Premier League club Southampton

- Yamao Yōzō - Member of the Choshu Five, see also Japanese students in the United Kingdom

Education

- In Japan

- British School in Tokyo

- In the UK

- Japanese School in London

- Rikkyo School in England

- Teikyo School United Kingdom

- Chaucer College

- Teikyo University of Japan in Durham

- Former institutions in the UK

- Gyosei International School UK (closed)

- Shi-Tennoji School in UK (closed)

- Gyosei International College in the U.K. (merged into the University of Reading)

List of Japanese diplomatic envoys in the United Kingdom (partial list)

Ministers plenipotentiary

- Terashima Munenori 1872–1873

- Kagenori Ueno 1874–1879

- Mori Arinori 1880–1884

- Masataka Kawase 1884–1893

- Aoki Shūzō 1894

- Katō Takaaki 1895–1900

- Hayashi Tadasu 1900–1905

Ambassadors

- Hayashi Tadasu 1905–1906

- Komura Jutarō 1906–1908

- Katō Takaaki 2nd time, 1908–1912

- Katsunosuke Inoue 1913–1916

- Chinda Sutemi 1916–1920

- Gonsuke Hayashi 1920–1925

- Keishiro Matsui 1925–1928

- Matsudaira Tsuneo 1929–1935

- Shigeru Yoshida 1936–1938

- Mamoru Shigemitsu 1938–1941

- Shunichi Matsumoto 1952–1955

- Haruhiko Nishi 1955–1957

- Katsumi Ōno 1958–1964

- Morio Yukawa 1968–1972

- Haruki Mori 1972–?

- Masaki Orita 2001–2004

- Yoshiji Nogami 2004–2008

- Shin Ebihara 2008–2011

- Keiichi Hayashi 2011–2016

- Koji Tsuruoka 2016–present

List of ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Japan

See also

- List of ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Japan

- History of Japanese foreign relations

- Ian Nish, historian

- Japanese entry into World War I

- British Japan Consular Service

- o-yatoi gaikokujin – foreign employees in Meiji era Japan

- Foreign cemeteries in Japan

- Japan Society of the UK

- Australia–Japan relations

- Canada–Japan relations

- China–Japan relations

- French–Japanese relations

- Germany–Japan relations

- Ireland–Japan relations

- Japan–Malaysia relations

- Japan–Netherlands relations

- Japan–New Zealand relations

- Japan–Russia relations

- Japan–Singapore relations

- Japan–South Korea relations

- Japan–United States relations

- Japanese in the United Kingdom, British people of Japanese descent

- Australia–United Kingdom relations

- Canada–United Kingdom relations

- China–United Kingdom relations

- Ireland–United Kingdom relations

- Malaysia–United Kingdom relations

- New Zealand–United Kingdom relations

- Singapore–United Kingdom relations

- South Korea–United Kingdom relations

- United Kingdom–United States relations

- Iwakura Mission, visits Europe 1871–1873

- gaikoku bugyō, commissioners of foreign affairs

- Chōshū Five, visits UK 1863

- Japanese students in the United Kingdom

- List of Westerners who visited Japan before 1868

Notes

- Samurai William, Giles Milton, 2003

- English Dreams and Japanese Realities: Anglo-Japanese Encounters Around the Globe, 1587-1673, Thomas Lockley, 2019, Revista de Cultura, p 126

- Stephen Turnbull, Fighting ships of the Far East (2), p 12, Osprey Publishing

- Notice at the Tower of London

- The Red Seal permit was re-discovered in 1985 by Professor Hayashi Nozomu, in the Bodleian Library. Massarella, Derek; Tytler Izumi K. (1990) "The Japonian Charters" Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp 189–205.

- Thierry Mormanne : "La prise de possession de l'île d'Urup par la flotte anglo-française en 1855", Revue Cipango, "Cahiers d'études japonaises", No 11 hiver 2004 pp. 209–236.

- Information about 1885–87 Japanese exhibition at Knightsbridge

- Phillips Payson O'Brien, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902–1922. (2004).

- William Langer, The Diplomacy of Imperialism 1890–1902 (2nd ed. 1950), pp. pp 745–86.

- John L. Hennessey, "Moving up in the world: Japan’s manipulation of colonial imagery at the 1910 Japan–British Exhibition." Museum History Journal 11.1 (2018): 24-41.

- Gowen, Robert (1971). "Great Britain and the Twenty-One Demands of 1915: Cooperation versus Effacement". The Journal of Modern History. University of Chicago. 43 (1): 76–106. ISSN 0022-2801.

- Malcolm Duncan Kennedy, The Estrangement of Great Britain and Japan, 1917-35 (Manchester UP, 1969).

- Gordon Lauren, Paul (1978). "Human Rights in History: Diplomacy and Racial Equality at the Paris Peace Conference". Diplomatic History. 2 (3): 257–278. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1978.tb00435.x.

- J. Bartlet Brebner, "Canada, the Anglo-Japanese alliance and the Washington conference." Political Science Quarterly 50.1 (1935): 45-58. online

- Bruce M. Petty, "Jump-Starting Japanese Naval Aviation." Naval History (2019) 33#6 pp 48-53.

- H. P. Willmott (2009). The Last Century of Sea Power: From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894–1922. Indiana U.P. p. 496.

- Paul W. Doerr (1998). British Foreign Policy, 1919–1939. p. 120.

- A.J.P. Taylor, English History: 1914–1945 (1965) pp 370–72.

- David Wen-wei Chang, "The Western Powers and Japan's Aggression in China: The League of Nations and" The Lytton Report"." American Journal of Chinese Studies (2003): 43–63. online

- Xiao Yiping, Guo Dehong, 中国抗日战争全史 Archived 4 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine、Chapter 87: Japan 's Colonial Economic Plunder and Colonial Culture, 1993.

- Thomas S. Wilkins, "Anatomy of a Military Disaster: The Fall of" Fortress Singapore" 1942." Journal of Military History 73.1 (2009): 221–230.

- Bond, Brian; Tachikawa, Kyoichi (2004). British and Japanese Military Leadership in the Far Eastern War, 1941–1945 Volume 17 of Military History and Policy Series. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 9780714685557.

- Peter Lowe, "After fifty years: the San Francisco Peace Treaty in the context of Anglo-Japanese relations, 1902–52." Japan Forum 15#3 (2003) pp 389–98.

- Protocole entre le Gouvernement du Japon et le Gouvernement de la République française, 1957. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan.

- "Ceremonies: State visits". Official web site of the British Monarchy. Archived from the original on 6 November 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- Mineko Iwasaki (2012). Geisha of Gion: The True Story of Japan's Foremost Geisha. p. 287.

- http://linguanews.com/php_en_news_read.php?section=s2&idx=2321

- The British-Japanese Parliamentary Group, About us, official site.

- Penguin Pocket On This Day. Penguin Reference Library. 2006. ISBN 0-14-102715-0.

- "UK: Akihito closes state visit". BBC News. 29 May 1998. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- "HRH The Duke of Cambridge to visit Japan and China – Focus on cultural exchange and creative partnerships". princeofwales.gov.uk/. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- Parker, George (4 September 2016). "Japan calls for 'soft' Brexit – or companies could leave UK". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "Kamall: UK can replicate new EU-Japan trade deal". Conservative Europe. 12 December 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- The History of Anglo-Japanese Relations, 1600–2000 (5 vol.) essays by scholars.

- Volume I: The Political-Diplomatic Dimension, 1600–1930 ed. by I. Nish and Y. Kibata. (2000) online chapter abstracts

- Volume II: The Political-Diplomatic Dimension, 1931–2000 ed by I. Nish and Y. Kibata. (2000) online chapter abstracts

- Volume III: The Military Dimension ed by I. Gow et al. (2003) online chapter abstracts

- Volume IV: Economic and Business Relations ed. by J. Hunter, and S. Sugiyama. (2002) online chapter abstracts

- Volume V: Social and Cultural Perspectives ed by G. Daniels and C. Tsuzuki. (2002) online chapter abstracts

- Akagi, Roy Hidemichi. Japan's Foreign Relations 1542–1936: A Short History (1979) online 560pp

- Auslin, Michael R. Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy (Harvard UP, 2009).

- Beasley, W.G. Great Britain and the Opening of Japan, 1834–1858 (1951) online

- Beasley, W. G. Japan Encounters the Barbarian: Japanese Travelers in America and Europe (Yale UP, 1995).

- Bennett, Neville. "White Discrimination against Japan: Britain, the Dominions and the United States, 1908–1928." New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 3 (2001): 91–105. online

- Best, Antony. "Race, monarchy, and the Anglo-Japanese alliance, 1902–1922." Social Science Japan Journal 9.2 (2006): 171–186.

- Best, Antony. British intelligence and the Japanese challenge in Asia, 1914–1941 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2002).

- Best, Antony. Britain, Japan and Pearl Harbour: Avoiding War in East Asia, 1936–1941 (1995) excerpt and text search

- Buckley, R. Occupation Diplomacy: Britain, the United States and Japan 1945–1952 (1982)

- Checkland, Olive. Britain’s Encounter with Meiji Japan, 1868–1912 (1989).

- Checkland, Olive. Japan and Britain after 1859: Creating Cultural Bridges (2004) excerpt and text search; online

- Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits edited by Hugh Cortazzi Global Oriental 2004, 8 vol (1996 to 2013)

- British Envoys in Japan 1859–1972, edited and compiled by Hugh Cortazzi, Global Oriental 2004, ISBN 1-901903-51-6

- Cortazzi, Hugh, ed. Kipling's Japan: Collected Writings (1988).

- Denney, John. Respect and Consideration: Britain in Japan 1853 – 1868 and beyond. Radiance Press (2011). ISBN 978-0-9568798-0-6

- Dobson, Hugo and Hook, Glenn D. Japan and Britain in the Contemporary World (Sheffield Centre for Japanese Studies/Routledge Series) (2012) excerpt and text search; online

- Fox, Grace. Britain and Japan, 1858–1883 (Oxford UP, 1969).

- Heere, Cees. Empire Ascendant: The British World, Race, and the Rise of Japan, 1894-1914 (Oxford UP, 2020).

- Kowner, Rotem. "'Lighter than Yellow, but not Enough': Western Discourse on the Japanese 'Race', 1854–1904." Historical Journal 43.1 (2000): 103–131. online

- Langer, William. The Diplomacy of Imperialism 1890–1902 (2nd ed. 1950), pp. pp 745–86, on treaty of 1902

- Lowe, Peter. Britain in the Far East: A Survey from 1819 to the Present (1981).

- Lowe, Peter. Great Britain and Japan 1911–15: A Study of British Far Eastern Policy (Springer, 1969).

- McOmie, William. The Opening of Japan, 1853–1855: A Comparative Study of the American, British, Dutch and Russian Naval Expeditions to Compel the Tokugawa Shogunate to Conclude Treaties and Open Ports to their Ships (Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental, 2006).

- McKay, Alexander. Scottish Samurai: Thomas Blake Glover, 1838–1911 (Canongate Books, 2012).

- Marder, Arthur J. Old Friends, New Enemies: The Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, vol. 1: Strategic illusions, 1936–1941(1981); Old Friends, New Enemies: The Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, vol. 2: The Pacific War, 1942–1945 (1990)

- Morley, James William, ed. Japan's foreign policy, 1868–1941: a research guide (Columbia UP, 1974), toward Britain, pp 184–235

- Nish, Ian Hill. China, Japan and 19th Century Britain (Irish University Press, 1977).

- Nish, Ian. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance: The Diplomacy of Two Island Empires 1984–1907 (A&C Black, 2013).

- Nish, Ian. Alliance in Decline: A Study of Anglo-Japanese Relations, 1908–23 (A&C Black, 2013).

- Nish, Ian. "Britain and Japan: Long-Range Images, 1900–52." Diplomacy & Statecraft (2004) 15#1 pp 149–161.

- Nish, I., ed. Anglo-Japanese Alienation, 1919–1952 (1982),

- Nish, Ian Hill. Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits (5 vol 1997–2004).

- O'Brien, Phillips, ed. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902–1922 (Routledge, 2004), Essays by scholars.

- Scholtz, Amelia. "The Giant in the Curio Shop: Unpacking the Cabinet in Kipling's Letters from Japan." Pacific Coast Philology 42.2 (2007): 199–216. online

- Scholtz, Amelia Catherine. Dispatches from Japanglia: Anglo-Japanese Literary Imbrication, 1880–1920. (PhD Diss. Rice University, 2012). online

- Sterry, Lorraine. Victorian Women Travellers in Meiji Japan (Brill, 2009).

- Takeuchi, Tatsuji. War and diplomacy in the Japanese Empire (1935); a major scholarly history online free in pdf

- Thorne, Christopher G. Allies of a kind: The United States, Britain, and the war against Japan, 1941–1945 (1978) excerpt and text search

- Thorne, Christopher G. The Limits of Foreign Policy: The West, The League and the Far Eastern Crisis of 1931–1933 (1973) online free to borrow

- Towle, Phillip and Nobuko Margaret Kosuge. Britain and Japan in the Twentieth Century: One Hundred Years of Trade and Prejudice (2007) excerpt and text search

- Woodward, Llewellyn. British Foreign Policy in the Second World War (History of the Second World War) (1962) ch 8

- Yokoi, Noriko. Japan's Postwar Economic Recovery and Anglo-Japanese Relations, 1948–1962 (Routledge, 2004).

External links

- A Bibliography of Anglo-Japanese relations – at Cambridge University

- The Asiatic Society of Japan – in Tokyo

- The British Association for Japanese Studies

- The British Consulate – in Nagoya

- The British Consulate-General – in Osaka

- The British Council in Japan – the cultural arm of the British government overseas

- The British Chamber of Commerce in Japan

- The British Embassy – in Tokyo

- The British Trade Promotion Office in Fukuoka (closed June 2005)

- The Cambridge & Oxford Society – founded in Tokyo in 1905

- The Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation – in London and Tokyo

- The Embassy of Japan – in London

- The Great Britain Sasakawa foundation – in London and Tokyo

- The Japan Society – founded in London in 1891

- The Japan-British Society – founded in Japan in 1908

- Japan-U.K. Relations at Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs Official Website.

- JETAA UK Japan Exchange and Teaching Programme Alumni Association United Kingdom