Erblande

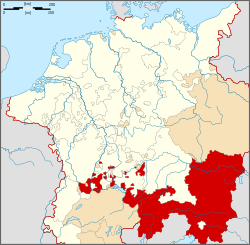

The Erblande (Hereditary Lands) of the House of Habsburg formed the Alpine heartland of the Habsburg Monarchy.[1] They were the hereditary possessions of the Habsburgs within the Holy Roman Empire from before 1526. The Erblande were not all unified under the head of the dynasty prior to the 17th century. They were divided into several groupings: the Archduchy of Austria, Inner Austria, the County of Tyrol and Further Austria.[2]

The Erblande did not include either the Lands of the Bohemian Crown or the Lands of the Hungarian Crown, since both monarchies were elective when the Habsburg Ferdinand I was elected to their thrones in 1526. Ferdinand divided the Erblande between his three heirs in 1564 and they were not reunited until 1665.[2] The Erblande were gathered into the Austrian Circle in 1512. This ensured a direct connection between the junior lines of the Austrian Habsburgs and the Empire after 1564, since throughout this period the Austrian Habsburgs exercised only one vote in the Council of Princes.[3]

Both the Bohemian and Hungarian nobilities lost their rights of royal election through defeat in battle. Following his victory in the Battle of White Mountain (1620) over the Bohemian rebels, Ferdinand II promulgated a Renewed Constitution (1627) that established hereditary succession. In his will and testament of 1621, Ferdinand II tried to establish the principle of primogeniture to ensure that the Erblande would not be divided again as in 1564. Following the Battle of Mohács (1687), in which Leopold I reconquered almost all of Hungary from the Ottoman Turks, the emperor held a diet in Pressburg to establish hereditary succession in the Hungarian kingdom.[4] Although the term Erblande was often extended to include Bohemia (which lay within the Holy Roman Empire) after 1627, it was never used to describe Hungary, even after 1687.[5]

Notes

- Kann, Habsburg Empire, 1–4.

- Ingrao, Habsburg Monarchy, 5–9.

- Winkelbauer, "Separation and Symbiosis", 174.

- Kann, Habsburg Empire, 55–57.

- Hochedlinger, Austria's Wars, xvii.

Sources

- Hochedlinger, Michael. Austria's Wars of Emergence: War, State and Society in the Habsburg Monarchy, 1683–1797. Routledge, 2013.

- Ingrao, Charles W. The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618–1815. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Kann, Robert A. A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. University of California Press, 1974.

- Winkelbauer, Thomas. "Separation and Symbiosis: The Habsburg Monarchy and the Empire in the Seventeenth Century". In Robert Evans and Peter Wilson (eds.), The Holy Roman Empire, 1495–1806: A European Perspective. Brill, 2012. pp. 167–184.