Banat Bulgarians

The Banat Bulgarians (Banat Bulgarian: Palćene or Banátsći balgare; common Bulgarian: Банатски българи, romanized: Banatski balgari; Romanian: Bulgari bănățeni; Serbian: Банатски Бугари / Banatski Bugari), also known as Bulgarian Roman Catholics and Bulgarians Paulicians or simply as Paulicians,[4] are a distinct Bulgarian minority group which since the Chiprovtsi Uprising in the late 17th century began to settle in the region of the Banat, which was then ruled by the Habsburgs and after World War I was divided between Romania, Serbia, and Hungary. Unlike most other Bulgarians, they are Roman Catholic by confession and stem from groups of Paulicians (who got Catholicized) and Roman Catholics from modern northern and northwestern Bulgaria.[5]

Bulgarian-inhabited places in the Banat Bulgarian population

City or town | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

12,000 (est.)[2] 3,000 (est.)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Banat (Romania, Serbia), Bulgaria, to a lesser extent Hungary, United States | |

| Languages | |

| Banat Bulgarian, common Bulgarian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bulgarians |

| Part of a series on |

| Bulgarians Българи |

|---|

|

| Culture |

|

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

|

| Language |

|

| Other |

|

Banat Bulgarians speak a distinctive codified form of the Eastern Bulgarian vernacular with much lexical influence from the other languages of the Banat. Although strongly acculturated to the Pannonian region (remote from Bulgaria's mainland), they have preserved their Bulgarian identity;[6] however, they consider themselves as Bulgarians among other ethnic groups but self-identify as Paulicians when compared to ethnic Bulgarians.[4][5]

Identity

The ethnic group in scholarly literature is called as Banat Bulgarians, Bulgarians Roman Catholics, Bulgarians Paulicians, or simply Paulicians (Pavlićani or Pavlikijani with dialectic forms Palćani, Palčene, Palkene). The latter ethnonym is used by the group members as self-identification (being endonym), and to express "I / we" which is contrasted to "you" of Bulgarian ethnonym (being exonym). Their Bulgarian identification is inconsistent and rather used when compared to other ethnic groups.[4][5] According to Blagovest Njagulov, there existed differences in self-designation among communities. In Romania, in the village of Dudeștii Vechi prevailed Paulician ethnonym, while in Vinga the Bulgarian ethnonym because in the latter was a mixture of Bulgarian communities from different regions. Until the mid-20th century was developed idea of Bulgarian ethnic nationalism and according to it prevailed Bulgarian ethnonym, with the intermediate decision being "Bulgarians Paulicians". As the community's literature and language is based on Paulician dialect and Latin alphabet it was promoted acceptance of Bulgarian literary language and Cyrillic alphabet. In the 1990s was again argued if they are a distinctive group or part of Bulgarian national, cultural and linguistic unity. On the other part, in Serbia the community was not in touch with such political influence and was accepted Paulician ethnonym, and only since 1990s became more in contact with other Bulgarian communities and institutions. According to 1999 research by Njagulov, the people consider to be partly of Bulgarian ethnos, but not on an individual level, only of a community, which is characterized by Catholic faith, specific literature and language practice as well elements of traditional material heritage and spiritual culture.[5]

History

Origin and migration north of the Danube

The origin of the Bulgarian Roman Catholic community is related to the Paulicianism, a medieval Christian movement from Armenia and Syria whose members between 8th and 10th century arrived in the region of Thrace, then controlled by Byzantine Empire.[7] They had religious freedom until the 11th century when the majority were Christianized to the official state faith by Alexios I Komnenos.[7] Over the centuries they started to assimilate with the Bulgarians, however never fully accepted the Orthodox Church, living with specific traditions.[7] The Roman Catholic Bosnian Franciscans in the late 16th and early 17th century managed to convert them to Catholicism.[5][7] It is considered that the Banat Bulgarian community was formed from two groups in different regions; one from missionary activities of the Roman Catholic Church in the 17th century among merchants and artisans from Chiprovtsi, not only of Paulician origin as included "Saxon" miners among others,[8][9] and other from Paulician peasants of villages from Svishtov and Nikopol municipalities.[5]

In 1688, the members of the community organized the unsuccessful Chiprovtsi Uprising against the Ottoman rule of Bulgaria.[10][8] The uprising was suppressed,[11] due to organizational flaws and the halting of the Austrian offensive against the Ottomans. Around 300 families of the surviving Catholics fled north of the Danube to Oltenia, initially settling in Craiova, Râmnicu Vâlcea, and other cities, where their existing rights were confirmed by Wallachian Prince Constantin Brâncoveanu.[12] Some moved to south-western Transylvania, founding colonies in Vinţu de Jos (1700) and Deva (1714) and receiving privileges such as civil rights and tax exemption.[13]

After Oltenia was occupied by Habsburg Monarchy in 1718,[12] the status of the Bulgarians in the region improved again, as an imperial decree of 1727 allowed them the same privileges as their colonies in Transylvania. This attracted another wave of migration of Bulgarian Catholics, about 300 families from the formerly Paulician villages of central northern Bulgaria. They settled in Craiova between 1726 and 1730, but did not receive the same rights as the colonists from Chiprovtsi.[14] The Habsburgs were forced to withdraw from Oltenia in 1737 in the wake of a new war with the Ottoman Empire. The Bulgarians fled from this new Ottoman occupation and settled in the Austrian-ruled Banat to the northwest. The Austrian authorities,[15] allowed 2,000 people to found the villages of Stár Bišnov in 1738 and some 125 families Vinga in 1741.[16][17] In 1744, a decree of Maria Theresa of Austria again confirmed their privileges received in Oltenia.[18]

Austrian and Hungarian rule

Around a hundred Paulicians from the region of Svishtov and Nikopol migrated to the Banat from 1753 to 1777.[19] The existing Bulgarian population, especially from Stár Bišnov,[16] quickly spread throughout the region from the late 18th to the second quarter of the 19th century. They settled in around 20 villages and towns in search of better economic conditions, specifically their need for arable land. Such colonies include those in Modoš (1779), Konak and Stari Lec (1820), Belo Blato (1825), Bréšća, Dénta, and Banatski Dvor (1842), Telepa (1846), Skorenovac (1866), and Ivanovo (1866-1868).[16][20]

After they settled, the Banat Bulgarians began to take care of their education and religion. The Neo-Baroque church in Stár Bišnov was built in 1804 and the imposing Neo-Gothic church in Vinga in 1892. Until 1863, Banat Bulgarians held liturgies in Latin and "Illyric". Illyric was a strain of Croatian which had spread in the communities before they migrated to the Banat. However, with their cultural revival in the mid-19th century, their vernacular was gradually introduced in the church. The revival also led to the release of their first printed book, Manachija kathehismus za katolicsanske Paulichiane, in 1851. "Illyric" was also substituted with Banat Bulgarian in education in 1860 (officially in 1864). In 1866, Jozu Rill codified the dialect with his essay Bálgarskotu pravopisanj.[21] After the Ausgleich of 1867, the Hungarian authorities gradually intensified the Magyarization of the Banat. Until World War I, they imposed Hungarian as the main language of education.[22]

Interwar Romanian and Serbian Banat

After World War I, Austria-Hungary was dissolved and Banat was divided between Romania and Serbia. Most Banat Bulgarians became citizens of the Kingdom of Romania, but many fell inside the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In Greater Romania, the Banat Bulgarians' identity was distinguished in censuses and statistics.[23] The main language of education was changed to Romanian and the Bulgarian schools were nationalized. A Romanian geography book of 1931 describes the Bulgarians in the county of Timiș-Torontal as "foreigners", and their national dress as "not as beautiful" as the Romanian one,[24] but in general the Banat Bulgarians were more favourably treated than the larger Eastern Orthodox Bulgarian minority in interwar Romania.[25]

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia denied the existence of any Bulgarian minority, whether in the Vardar Banovina, the Western Outlands, or the Banat. Official post-World War I statistics provide no data about the number of the Banat Bulgarians.[26] In comparison with the Eastern Orthodox Bulgarians in Yugoslavia, the Banat Bulgarians were treated better by the Yugoslav authorities,[27] although Serbo-Croatian was the only language of education.[28]

In the 1930s, the Banat Bulgarians in Romania entered a period of cultural revival led by figures such as Ivan Fermendžin, Anton Lebanov, and Karol Telbis (Telbizov).[29] These new cultural leaders emphasized the Bulgarian identity at the expense of the identification as Paulicians and Roman Catholics, establishing contacts with the Bulgarian government and other Bulgarian communities in Romania, particularly that in Dobruja. The organs of this revival were the newspaper Banatsći balgarsći glasnić (Banat Bulgarian Voice),[29] issued between 1935 and 1943, and the annual Banatsći balgarsći kalendar (Banat Bulgarian Calendar), issued from 1936 to 1940. There was a plan to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the settlement in the Banat which was the most significant manifestation by Banat Bulgarians in that period. It was partially spoiled by the Romanian authorities, but still attracted much attention among intellectuals in Bulgaria.[30] The Bulgarian Agrarian Party, a section of the National Peasants' Party, was founded in 1936 on the initiative of Karol Telbizov and Dr. Karol Manjov of Stár Bišnov,[31] with Petar Telbisz as its chairman,[32] and the Bulgarian National Society in the Banat, also headed by Telbisz, was established in 1939.

Bulgaria and Yugoslavia improved their relations in the 1930s, leading to indirect recognition of the Banat Bulgarian minority by the Yugoslav government. Still, the Banat Bulgarian revival was much less perceivable in the Serbian Banat. The Banat Bulgarian population in Yugoslavia was only partially affected by the work of Telbizov, Lebanov, and the other cultural workers in the Romanian Banat.[33]

Emigration to Hungary, the United States and Bulgaria

Some Banat Bulgarians migrated again, mainly to Hungary and the United States. According to Bulgarian data from 1942, 10,000 Banat Bulgarians lived in Hungary, mainly in the major cities, but this number is most likely overestimated,[34] as were assimilated in Serbian community.[35] Members of the Banat Bulgarian community in Hungary include several deputies to the National Assembly, such as Petar Dobroslav, whose son László Dobroslav (László Bolgár) was a diplomat, and Georgi Velčov.[36]

During the Interwar period, the Banat Bulgarian communities in Romania were among those experiencing the greatest emigration to the US, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s.[37] An organized Bulgarian community was established in Lone Wolf, Oklahoma, where the Banat Bulgarians were mostly farmers.[38]

A significant number of Banat Bulgarians returned to Bulgaria since 1878, called as "Banaćani" ("those from Banat").[10][5] They founded several villages in Pleven Province, Vratsa Province and Veliko Tarnovo Province and received privileges, as per the law of 1880, for the settlement of unpopulated lands. They introduced superior agricultural technologies to the country and fully applied their farming experience. Their religious life was partly determined by the clashes between the dominant Eastern Orthodoxy and the minority Catholicism, and cultural conflicts with other Roman Catholic communities which they lived with in several villages, such as the Banat Swabians and the Bulgarian Paulicians from Ilfov.[39] This migration would be final, although some did return to Banat.[5]

World War II and later

On the eve of World War II, the authoritarian regime of Carol II of Romania and the fascist government under Ion Antonescu widely discriminated against the Bulgarian minority in the Romanian Banat. Bulgarians were often deprived of property and land, subjected to anti-Bulgarian propaganda, and their villages had to shelter Romanian and Aromanian refugees from Northern Transylvania and Southern Dobruja.[40]

In May 1941, the Bulgarians in the Romanian Banat contributed to the release of ethnic Bulgarian prisoners of war from the Yugoslav Army, captured by the Axis, from a camp near Timișoara. Communicating with the Bulgarian state, Banat Bulgarian leaders headed by Anton Lebanov negotiated the prisoners' release and transportation to Bulgaria, after the example of the release of captured Hungarian soldiers from the Yugoslav Army. They temporarily accommodated these Bulgarians from Vardar Macedonia and the Serbian Banat and provided them with food until they could be taken to Bulgaria.[41]

The Serbian Banat was conquered by Nazi Germany on 12 April 1941, and was occupied for much of the war.[42] In late 1942, the German authorities allowed Bulgarian minority classes to be created in the Serbian schools in Ivanovo, Skorenovac, Konak, Belo Blato, and Jaša Tomić.[43] However, the sudden change in the war and German withdrawal from the Banat forced education in Bulgarian to be discontinued after the 1943–44 school year.[44]

After the war, Banat Bulgarians in Romania and Yugoslavia were ruled by communist regimes. In the Romanian Banat, some were deported in the Bărăgan deportations in 1951, but most of those were allowed to return in 1956–57.[45] A Bulgarian school was founded in Dudeștii Vechi in 1948, and in Vinga in 1949. Others followed in Breștea, Colonia Bulgară, and Denta, but these were briefly closed or united with the Romanian schools after 1952, and Bulgarian remained an optional subject.[46]

The Constitution of Romania of 1991 allowed Bulgarians in the Romanian Banat parliamentary representation through the minority party of the Bulgarian Union of the Banat — Romania (Balgarskotu družstvu ud Banát — Rumanija), led formerly by Karol-Matej Ivánčov and as of 2008 by Nikola Mirkovič,[47] and Bulgarian remained an optional subject in the schools.[48] In post-war Yugoslavia, the existence of a Banat Bulgarian minority was formally recognized, but they were not given the same rights as the larger Bulgarian minority in eastern Serbia. Unlike other minorities in Vojvodina, they were not allowed education in their mother tongue, only Serbo-Croatian.[49]

Language

| South Slavic languages and dialects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Western South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Eastern South Slavic

|

||||||

|

Transitional dialects

|

||||||

|

Alphabets

|

||||||

The vernacular of the Bulgarians of Banat can be classified as a Paulician dialect of the Eastern Bulgarian group. A typical feature is the "ы" (*y) vowel, which can either take an etymological place or replace "i".[2] Other characteristic phonological features are the "ê" (wide "e") reflex of the Old Church Slavonic yat and the reduction of "o" into "u" and sometimes "e" into "i": puljé instead of pole ("field"), sélu instead of selo ("village"), ugništi instead of ognište ("fireplace").[2] Another characteristic feature is the palatalization of final consonants, which is typical for other Slavic languages, but found only in non-standard dialects in Bulgarian (Bulgarian den ("day") sounds like and is written as denj).[50]

Lexically, the language has borrowed many words from languages such as German (such as drot from Draht, "wire"; gáng from Gang, "anteroom, corridor"), Hungarian (vilánj from villany, "electricity"; mozi, "cinema"), Serbo-Croatian (stvár from stvar, "item, matter"; ráčun from račun, "account"), and Romanian (šedinca from ședință, "conference")[51] due to the close contacts with the other peoples of the multiethnical Banat and the religious ties with other Roman Catholic peoples. Banat Bulgarian also has some older loanwords from Ottoman Turkish[52] and Greek, which it shares with other Bulgarian dialects (e.g. hirgjén from Turkish ergen, "unmarried man, bachelor"; trandáfer from Greek τριαντάφυλλο triantafyllo, "rose").[53] Loanwords constitute around 20% of the Banat Bulgarian vocabulary.[50][52] The names of some Banat Bulgarians are also influenced by Hungarian names, as the Hungarian (eastern) name order is sometimes used (family name followed by given name) and the female ending "-a" is often dropped from family names. Thus, Marija Velčova would become Velčov Marija.[54] Besides loanwords, the lexis of Banat Bulgarian has also acquired calques and neologisms, such as svetica ("icon", formerly used ikona and influenced by German Heiligenbild), zarno ("bullet", from the word meaning "grain"), oganbalváč ("volcano", literally "fire belcher"), and predhurta ("foreword").[50]

The Banat Bulgarian language until the mid-19th century used Bosnian Cyrillic alphabet due to Bosnian Franciscans influence,[5] since when it uses its own script, largely based on the Croatian version of the Latin alphabet (Gaj's Latin Alphabet), and preserves many features that are archaic in the language spoken in Bulgaria. The language was codified as early as 1866 and is used in literature and press, which distinguishes it from plain dialects.[50]

Alphabet

The following is the Banat Bulgarian Latin alphabet:[55][56]

| Banat Bulgarian Latin Cyrillic equivalents IPA | А а Ъ /ɤ/ | Á á А /a/ | B b Б /b/ | C c Ц /t͡s/ | Č č Ч /t͡ʃ/ | Ć ć Ќ (кь) /c/ | D d Д /d/ | Dz dz Ѕ (дз) /d͡z/ | Dž dž Џ (дж) /d͡ʒ/ | E e Е /ɛ/ | É é Ѣ /e/ |

| Latin Cyrillic IPA | F f Ф /f/ | G g Г /ɡ/ | Gj gj Ѓ (гь) /ɟ/ | H h Х /h/ | I i И /i/ | J j Й , Ь /j/ | K k К /k/ | L l Л /l/ | Lj lj Љ (ль) /ʎ/ | M m М /m/ | N n Н /n/ |

| Latin Cyrillic IPA | Nj nj Њ (нь) /ɲ/ | O o О /ɔ/ | P p П /p/ | R r Р /r/ | S s С /s/ | Š š Ш /ʃ/ | T t Т /t/ | U u У /u/ | V v В /v/ | Z z З /z/ | Ž ž Ж /ʒ/ |

Examples

| The Lord's Prayer in Banat Bulgarian:[57] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Banat Bulgarian | Bulgarian [58] | English |

| Baštá náš, kojtu si na nebeto: Imetu ti da se pusveti. | Отче наш, който си на небесата, да се свети името Твое, | Our father who art in heaven hallowed be thy name. |

| Kraljéstvotu ti da dodi. Olete ti da badi, | да дойде царството Твое, да бъде волята Твоя, | Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, |

| kaćétu na nebeto taj i na zemete. | както на небето така и на земята. | as in heaven so on earth. |

| Kátadenjšnija leb náš, dáj mu nám dnés. | Хляба наш насъщен дай ни днес, | Give us this day our daily bread. |

| I uprusti mu nám náša dalgj, | и прости нам дълговете наши, | And forgive us guilty as we are, |

| kaćétu i nija upráštemi na nášte dlažnici. | както и ние прощаваме на длъжниците ни, | as we also forgive our debtors. |

| I nide mu uvižde u nápas, | и не въведи ни в изкушение, | Also do not bring us into temptation, |

| negu mu izbávej ud zlo. | но избави ни от лукавия, | But free us from this evil. |

- Inscription about bishop Nikola Stanislavič in the Dudeștii Vechi church

Bilingual Banat Bulgarian (written in Latin letters)-Romanian plaque in Vinga

Bilingual Banat Bulgarian (written in Latin letters)-Romanian plaque in Vinga A rare occasion of Banat Bulgarian written in Cyrillic letters in Gostilya, Bulgaria

A rare occasion of Banat Bulgarian written in Cyrillic letters in Gostilya, Bulgaria

Culture

Banat Bulgarians have engaged in literary activity since they settled in the Banat. Their earliest preserved literary work is the historical record Historia Domus (Historia Parochiae Oppidi Ó-Bessenyö, in Diocesi Czanadiensi, Comitatu Torontalensi), written in Latin in the 1740s. The codification of the Banat Bulgarian vernacular in 1866 enabled the release of a number of school books and the translation of several important religious works in the mid-19th century.[59] There was a literary revival in the 1930s, centered around the Banatsći balgarsći glasnić newspaper. Today, the Bulgarian Union of the Banat – Romania issues the biweekly newspaper Náša glás and the monthly magazine Literaturna miselj.[60]

The music of the Banat Bulgarians is classed as a separate branch of Bulgarian folk music, with several verbal and musical peculiarities. While the typically Bulgarian bars have been preserved, a number of melodies display Romanian, Serbian, and Hungarian influences, and the specific Bulgarian Christmas carols have been superseded by urban-type songs. Roman Catholicism has exerted considerable influence, eliminating certain types of songs and replacing them with others.[61] Similarly, Banat Bulgarians have preserved many Bulgarian holidays but also adopted others from other Roman Catholic peoples.[62] One of the most popular holidays is Faršángji, or the Carnival.[63] In terms of dances, Banat Bulgarians have also heavily borrowed from the neighbouring peoples, for example Hungarian csárdás.[61]

The women's national costume of the Banat Bulgarians has two varieties. The costume of Vinga is reminiscent of those of sub-Balkan cities in Bulgaria; the one of Stár Bišnov is characteristic of northwestern Bulgaria. The Vinga costume has been particularly influenced by the dress of Hungarians and Germans, but the Stár Bišnov costume has remained more conservative.[64] The Banat Bulgarian women's costume is perceived as particularly impressive with its crown-like headdress.[61]

A formal Banat Bulgarian female costume dating to the 19th century

A formal Banat Bulgarian female costume dating to the 19th century Historia Domus, the earliest chronicle of the Banat Bulgarians

Historia Domus, the earliest chronicle of the Banat Bulgarians- Liturgy in the Bulgarian church in Dudeștii Vechi

Demography

In 1963 was estimated that approximately lived 18,000 Banat Bulgarians in Banat, of which 12,000 in Romanian, and 6,000 in Serbian part of the region. In 2008 was estimated half of the previous population in Serbia,[2][5] while in 2013 between 4,000-4,500 people.[3] However, according to Romanian 2002 census circa 6,468 people of Banat Bulgarian origin inhabited the Romanian part of the region,[65] of which 3,000 in Stár Bišnov, making it half of 1963's estimation.[3] The Serbian 2002 census recognized 1,658 Bulgarians in Vojvodina, the autonomous province that covers the Serbian part of the Banat.[66] However it includes Orthodox Bulgarians and hence the number of Catholic Bulgarians is smaller by two-thirds compared to previous estimation.[3] The 2011 census are even more vague to understand the actual numbers, but the numbers are probably declining.[3]

The earliest and most important centers of the Banat Bulgarian population are the villages of Dudeştii Vechi (Stár Bišnov) and Vinga, both today in Romania,[67] but notable communities also exist in Romania in Breştea (Bréšća), Colonia Bulgară (Telepa) and Denta (Dénta),[10] and the cities of Timișoara (Timišvár) and Sânnicolau Mare (Smikluš), as well as in Serbia in the villages of Ivanovo, Belo Blato, Konak (Kanak), Jaša Tomić (Modoš), Skorenovac (Gjurgevo), as well cities of Pančevo, Zrenjanin, Vršac and Kovin.[5][68]

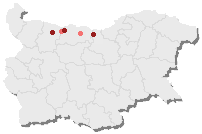

In Bulgaria, returning Banat Bulgarians populated the villages of Asenovo, Bardarski Geran, Dragomirovo, Gostilya, and Bregare,[10] among others, in some of which they coexist or coexisted with Banat Swabians, other Bulgarian Roman Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox Bulgarians.[69]

In Banat, the people mainly intermarried within the group, and only since the 1940s began intensive marriages with other nationalities, because of which many got assimilated, especially according to confessional factor (among Slovaks and Hungarians, while few among Croats, Serbs and so on).[70]

Historical population

According to various censuses and estimates, not always accurate, the number of the Banat Bulgarians varied as follows:[71]

| Source | Date | Population | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romania | Serbia | |||

| Jozu Rill | 1864 | 30,000–35,000 | ||

| Hungarian statistics | 1880 | 18,298 | ||

| Hungarian statistics | 1900 | 19,944 | ||

| Hungarian statistics | 1910 | 13,536 | "evidently underestimated"[68] | |

| Various authors | second half of the 19th century | 22,000–26,000 | "sometimes including the Krashovani"[68] | |

| Romanian census | 1930 | 10,012 | Romanian Banat only | |

| Dimo Kazasov | 1936 | 3,200 | Serbian Banat only; estimated | |

| Romanian census | 1939 | 9,951 | Romanian Banat only | |

| Karol Telbizov | 1940 | 12,000 | Romanian Banat only; estimated | |

| Mihail Georgiev | 1942 | up to 4,500 | Serbian Banat only; estimated[72] | |

| Romanian census | 1956 | 12,040 | Romania only[73] | |

| Yugoslav census | 1971 | 3,745 | Serbian Banat only[74] | |

| Romanian census | 1977 | 9,267 | Romania only[73] | |

| Romanian census | 2002 | 6,486 | Romania only[1] | |

| Serbian census | 2002 | 1,658 | Serbia only[75] | |

Notable figures

- Colonel Stefan Dunjov (1815–1889) – revolutionary, participant in the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, and member of Giuseppe Garibaldi's forces during the Italian unification

- Eusebius Fermendžin (1845–1897) – historian, high-ranking Franciscan cleric, theologian, polyglot, and active member of the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Leopold Kossilkov (1850–1940) – teacher and writer[76]

- Jozu Rill – 19th-century teacher and internationally acclaimed textbook writer; codified the Banat Bulgarian orthography and grammar in 1866

- Carol Telbisz (1853–1914) – long-time mayor of Timișoara (1885–1914)

- Anton Lebanov (1912–2008) – lawyer, journalist, and poet[76]

- Karol Telbizov (1915–1994) – lawyer, journalist, and scientist[77][78]

- Luis Bacalov (b. 1933) — Academy Award-winning Argentine composer[79]

Footnotes

- "Structura Etno-demografică a României" (in Romanian). Centrul de Resurse pentru Diversitate Etnoculturală. 2008-07-24.

- Иванова, Говорът и книжовноезиковата практика на българите-католици от сръбски Банат.

- Nomachi, Motoki (2016). "The Rise, Fall, and Revival of the Banat Bulgarian Literary Language: Sociolinguistic History from the Perspective of Trans-Border Interactions". The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 394–428. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Vučković, Marija (2008). "Болгары — это мы или другие? (Само)идентификация павликан из Баната" [Bulgarians – We or the Others? (Self)identification of Paulicians from Banat]. Etnolingwistyka. Problemy Języka i Kultury. 20: 333–348. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Vučković, Marija (2008). "Savremena istraživanja malih etničkih zajednica" [Contemporary studies of small ethnic communities]. XXI Vek (in Serbo-Croatian). 3: 2–8. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Zatykó Vivien (1994). "Magyar bolgárok? Etnikus identitás és akkulturáció a bánáti bolgárok körében". REGIO folyóirat (in Hungarian). Archived from the original (– Scholar search) on September 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- Nikolin, Svetlana (2008). "Pavlikijani ili banatski Bugari" [Paulicians or Banat Bulgarians]. XXI Vek (in Serbo-Croatian). 3: 15–16. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Чолов, Петър (1988). Чипровското въстание 1688 г. (in Bulgarian). София: Народна просвета. ISBN 0-393-04744-X. Archived from the original on 2007-04-01.

- Гюзелев, Боян (2004). Албанци в Източните Балкани (in Bulgarian). София: IMIR. ISBN 954-8872-45-5.

- Kojnova, Marija. "Catholics of Bulgaria" (PDF). Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe – Southeast Europe.

- Kojnova, Marija. "Catholics of Bulgaria" (PDF). Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe — Southeast Europe.

- Maran, Mirča (2008). "Bugari u Banatu i njihovi odnosi sa Rumunima" [Bulgarians in Banat and their relationships with Romanians]. XXI Vek (in Serbo-Croatian). 3: 17–18. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Ivanciov, Istorijata i tradicijite na balgarskotu malcinstvu ud Rumanija.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 19-20.

- Милетич, Изследвания за българите в Седмиградско и Банат, p. 243.

- "Najznačajnija mesta u kojima žive Palćeni" [Most important places in which live Paulicians]. XXI Vek (in Serbo-Croatian). 3: 9–12. 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- According to the earliest entries in the local birth and wedding records. Ронков, Яку (1938). "Заселването в Банат". История на банатските българи (in Bulgarian). Тимишоара: Библиотека "Банатски български гласник". Archived from the original on 2007-02-26.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 20-21.

- Гандев, Христо; et al. (1983). История на България, том 4: Българският народ под османско владичество (от XV до началото на XVIII в.) (in Bulgarian). София: Издателство на БАН. p. 249. OCLC 58609593.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 22.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 27-30.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 30.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 56.

- Nisipeanu, I.; T. Geantă, L. Ciobanu (1931). Geografia judeţului Timiş-Torontal pentru clasa II primară (in Romanian). Bucharest. pp. 72–74.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 70.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 75.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 78.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 80.

- Коледаров, Петър (1938). "Духовният живот на българите в Банатско". Славянска Беседа (in Bulgarian).

- Нягулов, "Ново етно-културно възраждане в Банат", Банатските българи, pp. 141-195.

- Banatsći balgarsći glasnić (5) (in Bulgarian). 2 February 1936.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 230.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 196-200.

- Динчев, Х. (1936). "Банатци". Нация и политика (in Bulgarian). p. 18.

- Sikimić, Biljana (2008). "Bugari Palćani: nova lingvistička istraživanja" [Bulgarians Paulicians: New linguistic studies]. XXI Vek (in Serbo-Croatian). 3: 22–29. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 82-83.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 84.

- Трайков, Веселин (1993). История на българската емиграция в Северна Америка (in Bulgarian). Sofia. pp. 35, 55, 113.

- Нягулов, "Банатските българи в България", Банатските българи, pp. 87-142.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 252-258.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 263-265.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 286-287.

- ЦДА, ф. 166к, оп. 1, а.е. 503, л. 130-130а.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 295.

- Mirciov, R. (1992). Deportarea în Baragan 1951–1956. Scurtă istorie a deportăţilor din Dudeşti vechi (in Romanian). Timișoara.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 294-295, p. 302.

- "Deputáta Nikola Mirkovič ij bil izbrán predsedátel na B.D.B.-R" (PDF). Náša glás (in Bulgarian) (1). 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-10.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 305-306.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 312-316.

- Стойков, Банатски говор.

- Etymology from Gaberoff Koral German Dictionary (German), MTA SZTAKI (Hungarian), Serbian-English Dictionary Archived 2009-10-06 at the Wayback Machine (Serbo-Croatian) and Dictionare.com Archived 2010-10-28 at the Wayback Machine (Romanian).

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 27.

- See Sveta ud pukraj námu posts #127 and #128 for the words in use. Etymology from Seslisozluk.com (Turkish) and Kypros.org Lexicon (Greek).

- For another example, see Náša glás Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine of 1 March 2007, p. 6.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 11.

- Стойков, Стойко (1967). Банатският говор (in Bulgarian). Издателство на БАН. pp. 21–23. OCLC 71461721.

- Svetotu pismu: Novija zákun (in Bulgarian). Timișoara: Helicon. 1998. ISBN 973-574-484-8.

- bg:wikisource:Отче наш

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 32-37.

- "Периодични издания и електронни медии на българските общности в чужбина" (in Bulgarian). Агенция за българите в чужбина. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- Кауфман, Николай (2002). "Песните на банатските българи". Северозападна България: Общности, Традиции, Идентичност. Регионални Проучвания На Българския Фолклор (in Bulgarian). София. ISSN 0861-6558.

- Янков, Ангел (2002). "Календарните празници и обичаи на банатските българи като белег за тяхната идентичност". Северозападна България: Общности, Традиции, Идентичност. Регионални Проучвания На Българския Фолклор (in Bulgarian). София. ISSN 0861-6558.

- "(Euro)Faršángji 2007" (PDF). Náša glás (in Bulgarian) (4). 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-18.

- Телбизова, М; К. Телбизов (1958). Народната носия на банатските българи (in Bulgarian). София. pp. 2–3.

- "Structura etno-demografică pe arii geografice: Reguine: Vest" (in Romanian). Centrul de Resurse pentru Diversitate Etnoculturală. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- Final results of the Census 2002: Population by national or ethnic groups, gender and age groups in the Republic of Serbia, by municipalities (PDF). Republic of Serbia: Republic Statistical Office. 24 December 2002. p. 2. ISSN 0353-9555.

- Караджова, Светлана (28 November 1998). Банатските българи днес – историята на едно завръщане (in Bulgarian). София. ISBN 0-03-095496-7. Archived from the original on February 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 23.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, p. 92.

- Ivanova, Cenka (2008). "O nosiocima bugarskog jezika u Srbiji u prošlosti i danas" [About the holders of Bulgarian language in Serbia in the past and today]. XXI Vek (in Serbo-Croatian). 3: 32–35. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 22-23, 56-57, 79.

- ЦДА, ф. 176к, оп. 8, а.е. 1014.

- Also including other Bulgarian communities in Romania, accounting for around 10% of that number. Панайотов, Г. (1992). "Съвременни аспекти на националния проблем в Румъния". Национални Проблеми На Балканите. История И Съвременност (in Bulgarian). София: 263–265.

- Socialistička Autonomna Pokrajina Vojvodina (in Serbian). Beograd. 1980. pp. 121–122.

- "Final results of the Census 2002" (PDF). Republic of Serbia: Republic Statistical Office. 2008-07-24.

- Nikolin, Svetlana (2008). "Istaknute ličnosti banatskih Bugara" [Prominent Banat Bulgarians]. XXI Vek (in Serbo-Croatian). 3: 20–21. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Нягулов, Банатските българи, pp. 348-354, 359-366.

- "The Bulgarians". Festivalul Proetnica 2006. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- Moskov, Nikolay (2013-02-01). "The composer of Django Unchained - a Banat Bulgarian". 24 Chasa (in Bulgarian). Sofia: VGB. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

References

- Иванова, Ценка; Ничка Баева. Говорът и книжовноезиковата практика на българите-католици от сръбски Банат (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- Милетич, Любомир; Симеон Дамянов; Мария Рунтова (1987). Изследвания за българите в Седмиградско и Банат (in Bulgarian). София: Наука и изкуство. OCLC 19361300.

- Нягулов, Благовест (1999). Банатските българи. Историята на една малцинствена общност във времето на националните държави (in Bulgarian). София: Парадигма. ISBN 978-954-9536-13-3.

- Пейковска, Пенка (2014). "Етнодемографска характеристика на банатските българи в Унгария през втората половина на XIX и в началото на ХХ век". Личност, народ, история. Националноосвободителните борби през периода XV-ХІХ в. (in Bulgarian) (първо издание ed.). София: Институт "Балаши"-Унгарски културен институт, София-Исторически музей-Чипровци-Гера-Арт. pp. 88–118. ISBN 978-954-9496-19-2.

- Peykovska, Penka. "Írás-olvasástudás és analfabetizmus a többnemzetiségű Bánságban a 19. század végén és a 20. század elején: a római katolikus bolgárok és szomszédaik esete.". Bácsország (Vajdasági Honismereti Szemle), Szabadka/Subotica, 75. (2015) (in Hungarian).

- Стойков, Стойко (2002) [1962]. "Банатски говор". Българска диалектология (in Bulgarian) (четвърто издание ed.). София: Проф. Марин Дринов. pp. 195–197. ISBN 954-430-846-6.

- Prof. Ivanciov Margareta (2006). Istorijata i tradicijite na balgarskotu malcinstvu ud Rumanija (PDF) (in Bulgarian). Timișoara: Balgarsku Družstvu ud Banát – Rumanija, Editura Mirton. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-05.

- Duličenko, Alexander D. "Banater Bulgarisch" (PDF). Enzyklopädie des Europäischen Ostens (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

- Lučev, Detelin (2004–2005). "To the problem of the ethnographic investigations of the internet communities (bulgariansfrombanat_worldwide case study)". Sociologija i Internet. Archived from the original on 7 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- Георгиев, Любомир (2010). Българите католици в Трансилвания и Банат (XVIII - първата половина на ХІХ в.) (in Bulgarian). София. ISBN 0-9688834-0-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Banat Bulgarians. |

- The website of Náša glás and Literaturna miselj, offers PDF versions of both publications, as well as information about the Banat Bulgarians and a library (in Banat Bulgarian)

- The spiritual life of the Banat Bulgarians, featuring 1938 publications (in Bulgarian)

- Penka Peykovska. Literacy and Illiteracy in Austria-Hungary: The Case of the Bulgarian Migrant Communities

- BANATerra, a "becoming encyclopedia of the Banat", version in Banat Bulgarian. Includes diverse information and resources pertaining to the Banat Bulgarians.

- Falmis, Association of the Banat Bulgarians in Bulgaria (in Bulgarian)

- Sveta ud pukraj námu, Nick Markov's blog in Banat Bulgarian

- Falmis, Svetlana Karadzhova's blog about the Banat Bulgarians (in Bulgarian)

- Star Bisnov, Website for Banat Bulgarian people