Anglo-Saxon runes

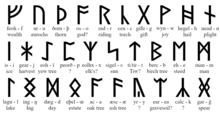

Anglo-Saxon runes (Old English: rūna) are runes used by the early Anglo-Saxons as an alphabet in their writing system. The characters are known collectively as the futhorc (fuþorc) (also spelled futhark or futhork),[1] from the Old English sound values of the first six runes. The futhorc was a development from the 24-character Elder Futhark. Since the futhorc runes are thought to have first been used in Frisia before the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, they have also been called Anglo-Frisian runes.[2] They were likely used from the 5th century onward, recording Old English and Old Frisian.

| Futhorc | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Alphabet

|

| Languages | Old English and Old Frisian |

Time period | 5th through 11th centuries |

Parent systems | Phoenician alphabet

|

Sister systems | Younger Futhark |

| This article is part of the series: |

| Anglo-Saxon society and culture |

|---|

|

| People |

| Language |

| Material culture |

|

| Power and organization |

|

| Religion |

|

They were gradually supplanted in Anglo-Saxon England by the Old English Latin alphabet introduced by Irish missionaries. Futhorc runes were no longer in common use by the eleventh century, but the Byrhtferth Manuscript (MS Oxford St John's College 17) indicates that fairly accurate understanding of them persisted into at least the twelfth century.

History

There are competing theories about the origins of the Anglo-Saxon futhorc. One theory proposes that it was developed in Frisia and from there later spread to Britain. Another holds that runes were first introduced to Britain from the mainland where they were then modified and exported to Frisia. Both theories have their inherent weaknesses, and a definitive answer may come from further archaeological evidence.

The early futhorc was nearly identical to the Elder Futhark, except for the split of ᚨ a into three variants ᚪ āc, ᚫ æsc and ᚩ ōs, resulting in 26 runes. This was done to account for the new phoneme produced by the Ingvaeonic split of allophones of long and short a. The earliest ᚩ ōs rune is found on the 5th-century Undley bracteate. ᚪ āc was introduced later, in the 6th century. The double-barred ᚻ hægl characteristic of continental inscriptions is first attested as late as 698, on St Cuthbert's coffin; before that, the single-barred variant was used.

In England the futhorc expanded. Runic writing in England became closely associated with the Latin scriptoria from the time of Anglo-Saxon Christianization in the 7th century. The futhorc started to be replaced by the Latin alphabet from around the 7th century, but it was still sometimes used up until the 10th or 11th century. In some cases, texts would be written in the Latin alphabet, and þorn and ƿynn came to be used as extensions of the Latin alphabet. By the Norman Conquest of 1066, it was very rare and disappeared altogether shortly thereafter. From at least five centuries of use, fewer than 200 artefacts bearing futhorc inscriptions have survived.

Several famous English examples mix runes and Roman script, or Old English and Latin, on the same object, including the Franks Casket and St Cuthbert's coffin; in the latter, three of the names of the Four Evangelists are given in Latin written in runes, but "LUKAS" (Saint Luke) is in Roman script. The coffin is also an example of an object created at the heart of the Anglo-Saxon church that uses runes. A leading expert, Raymond Ian Page, rejects the assumption often made in non-scholarly literature that runes were especially associated in post-conversion Anglo-Saxon England with Anglo-Saxon paganism or magic.[3]

Letters

The letter sequence and letter inventory of futhorc, along with the actual sounds made by those letters could vary depending on location and time. That being so, an authentic and unified list of runes is not possible.

Rune inventory

| Image | UCS | Name | Name meaning | Transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᚠ | feoh | wealth, cattle | f | /f/, [v] (word-medial allophone of /f/) | |

| ᚢ | ūr | aurochs | u | /u(ː)/ | |

| ᚦ | þorn | thorn | þ | /θ/, ð (word-medial allophone of /θ/) | |

| ᚩ | ōs | god, or mouth (Latin) | o | /o(ː)/ | |

| ᚱ | rād | riding | r | /r/ | |

| ᚳ | cēn | torch | c | /k/, /kʲ/, /tʃ/ | |

| ᚷ | gyfu | gift | g | /ɡ/, ɣ (word-medial allophone of /ɡ/), /j/, /x/?, /gʲ/? | |

| ᚹ | ƿynn | mirth | w | /w/ | |

| ᚻ | hægl | hail (as in "precipitation") | h | /h/, /x/, ç (allophone of /x/ before and after frontal vowels) | |

| ᚾ | nȳd | need (as in "plight") | n | /n/ | |

| ᛁ | īs | ice | i | /i(ː)/ | |

| ᛡ/ᛄ | gēr | year (as in "harvest time"?) | j | /j/ | |

| ᛇ | ēoh | yew-tree | ï, ʒ | /i(ː)/? /x/, ç (allophone of /x/ before and after frontal vowels) | |

| ᛈ | peorð | (unknown) | p | /p/ | |

| ᛉ | eolhx | elk's | x | /ks/ | |

| ᛋ/ᚴ | sigel | sun (but rune poem implies "sail") | s | /s/, [z] (word-medial allophone of /s/) | |

| ᛏ | Tī, Tīr | Tiw? Mars (mythology)?[4] | t | /t/ | |

| ᛒ | beorc | birch-tree | b | /b/ | |

| ᛖ | eh | steed | e | /e(ː)/ | |

| ᛗ | mann | man | m | /m/ | |

| ᛚ | lagu | lake (as in "body of water") | l | /l/ | |

| ᛝ | Ing | Ing (Ingui-Frea)? | ŋ | /ŋg/, /ŋ/ | |

| ᛟ | ēðel | ethel (homeland, estate) | œ | /ø(ː)/ | |

| ᛞ | dæg | day | d | /d/ | |

| ᚪ | āc | oak-tree | a | /ɑ(ː)/ | |

| ᚫ | æsc | ash-tree | æ | /æ(ː)/ | |

| ᚣ | ȳr | yewen bow? | y | /y(ː)/ | |

| ᛡ | īor | beaver?[5] eel? | N/A | /i(ː)o/? | |

| ᛠ | ēar | grave soil? | ea | /æ(ː)ɑ/ |

The sequence of the runes above comes from the surviving modern copy of the Anglo-Saxon rune poem which was based on the now-destroyed Cotton Otho B.x.165 manuscript. The first 24 of these runes directly continue the elder futhark letters, and do not deviate in sequence (though ᛞᛟ rather than ᛟᛞ is an attested sequence in both elder futhark and futhorc). The next 5 runes represent additional vowels (a, æ, y, io, ea), comparable to the five forfeda of the ogham alphabet.

While the rune poem and some manuscripts present ᛡ as "ior", and ᛄ as "ger", epigraphically both are variants of ger. R. I. Page designated ior a pseudo-rune.[6]

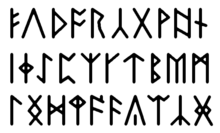

| Image | UCS | Name | Name meaning | Transliteration | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᛣ | calc | chalk? chalice? sandal? | k | /k/ | |

| ᛤ | (unknown) | (unknown) | k̄ | /k/ | |

| ᚸ | gar | spear | ḡ | /g/, [ɣ] (word-medial allophone of /g/) | |

| ᛢ | cweorð | (unknown) | q | /k/? (for writing Latin?) | |

| ᛥ | stan | stone | N/A | /st/ | |

| N/A | (unknown) | (unknown) | ę, ᴇ | /ǝ/? | |

| N/A | (unknown) | (unknown) | ᶖ | /e(ː)o/? /i(ː)o/? |

The runes above (in no particular order) were not included in the rune poem. Calc appears in manuscripts, and epigraphically on the Ruthwell Cross, the Bramham Moor Ring, the Kingmoor Ring, and elsewhere. Gar appears in manuscripts, and epigraphically on the Ruthwell Cross and probably on the Bewcastle Cross.[7] The unnamed ᛤ rune only appears on the Ruthwell Cross, where it seems to take calc's place as /k/ where that consonant is followed by a secondary fronted vowel. Cweorð and stan only appear in manuscripts. The unnamed ę rune only appears on the Baconsthorpe Grip. The unnamed ᶖ rune only appears on the Sedgeford Handle.

There is little doubt that calc and gar are modified forms of cen and gyfu, and that they were invented to address the ambiguity which arose from /k/ and /g/ spawning palatalized offshoots.[8] R. I. Page designated cweorð and stan pseudo-runes, noting their apparent pointlessness, and speculating that cweorð was invented merely to give futhorc an equivalent to Q.[9] The ę rune is likely a local innovation, possibly representing an unstressed vowel, and may derive its shape from ᛠ.[10] The unnamed ᶖ rune is found in a personal name (bᶖrnferþ), where it stands for a vowel or diphthong. Anglo-Saxon expert Gaby Waxenberger speculates that ᶖ may not be a true rune, but rather a bindrune of ᛁ and ᚩ, or the result of a mistake.[11]

Combinations and digraphs

Various runic combinations are found in the futhorc corpus. For example, the sequence ᚫᚪ appears on the Mortain Casket where ᛠ could theoretically have been used.

| Combination | IPA | Word | Meaning | Found on |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᚩᛁ | /oi/ (?) | ]oin[.] | (unknown) | Lindisfarne Stone II |

| ᚷᚳ | [gg] (?), [ddʒ] (?) | blagcmon | (personal name) | Maughold Stone I |

| ᚷᚷ | ~[ddʒ] | eggbrect | (personal name) | (an armband from the Galloway Hoard) |

| ᚻᚹ | /ʍ/ | gehwelc | each | Honington Clip |

| ᚻᛋ | /ks/ (likely [xs]) | wohs | to wax | Brandon Antler |

| ᚾᚷ | /ŋg/ | hring | ring | Wheatley Hill Silver-Gilt Finger-Ring |

| ᛁᚷ | /ij/ | modig | proud/bold/arrogant | Ruthwell Cross |

| ᛇᛡ (?) | ~/ij/ (?) | hælïj (?) | holy (?) | Gandersheim Casket |

| ᛇᛋ | /ks/ (likely [xs]) | BennaREïs | king Benna | (a coin of Beonna of East Anglia) |

| ᛋᚳ | /sk/, /ʃ/ | fisc | fish | Franks Casket |

| ᛖᚩ | /eo/, /eːo/ | eoh | (personal name) | Kirkheaton Stone |

| ᛖᚷ | /ej/ | legdun | laid | Ruthwell Cross |

| ᛖᛇ | ~/ej/, [eʝ] (?) | eateïnne | (personal name) | Thornhill Stone II |

| ᛖᚪ | /æɑ/, /æːɑ/ | eadbald | (personal name) | Santi Marcellino e Pietro al Laterano Graffiti |

| ᚪᚢ | ~/ɑu/ | saule | soul | Thornhill Stone III |

| ᚪᛁ | /ɑi/ (?) | desaiona | (gibberish?) | (a gold shilling from Suffolk) |

| ᚪᛡ | /ɑj/ (?), /ɑx/ (?) | fajhild? faghild? | (personal name) | Santi Marcellino e Pietro ad Duas Lauros Graffiti |

| ᚫᚢ | ~/æu/ | dæus | deus (Latin) | Whitby Comb |

| ᚫᚪ | /æɑ/, /æːɑ/ | æadan | (personal name) | Mortain Casket |

Usage and culture

A rune in Old English could be called a "rúnstæf" (perhaps meaning something along the lines of "mystery letter" or "whisper letter"), or simply "rúne".

Futhorc inscriptions hold diverse styles and contents. Ocher has been detected on at least one English runestone, implying its runes were once painted. Bind runes are not uncommon in futhorc (relative to its small corpus), and were seemingly used most often to ensure the runes would fit in a limited space.[12] Futhorc logography is attested to in a few manuscripts. This was done by having a rune stand for its name, or a similar sounding word. In the sole extant manuscript of the poem Beowulf, the ēðel rune was used as a logogram for the word ēðel (meaning "homeland", or "estate").[13] Both the Hackness Stone and Codex Vindobonensis 795 attest to futhorc Cipher runes.[14] In one manuscript (Corpus Christi College, MS 041) a writer seems to have used futhorc runes like Roman numerals, writing ᛉᛁᛁ⁊ᛉᛉᛉᛋᚹᛁᚦᚩᚱ, which likely means "12&30 more".[15]

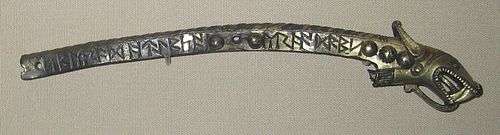

There is some evidence of futhorc rune magic. Sword pommels (such as the artefact indexed as IOW-FC69E6) have been found in England which seem to bear ᛏ runes which may be akin to magical runes spoken of in Norse myth. The possibly magical alu sequence seems to appear on an urn found at Spong Hill in spiegelrunes (runes whose shapes are mirrored). In a tale from Bede's Ecclesiastical History (written in Latin), a man named Imma cannot be bound by his captives and is asked if he is using "litteras solutorias" (loosening letters) to break his binds. In one Old English translation of the passage, Imma is asked if he is using "drycraft" (magic, druidcraft) or "runestaves" to break his binds.[16] Furthermore, futhorc rings have been found with what appear to be enchanted inscriptions for the stanching of blood.[17]

Inscription corpus

The Old English and Old Frisian Runic Inscriptions database project at the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, Germany aims at collecting the genuine corpus of Old English inscriptions containing more than two runes in its paper edition, while the electronic edition aims at including both genuine and doubtful inscriptions down to single-rune inscriptions.

The corpus of the paper edition encompasses about one hundred objects (including stone slabs, stone crosses, bones, rings, brooches, weapons, urns, a writing tablet, tweezers, a sun-dial, comb, bracteates, caskets, a font, dishes, and graffiti). The database includes, in addition, 16 inscriptions containing a single rune, several runic coins, and 8 cases of dubious runic characters (runelike signs, possible Latin characters, weathered characters). Comprising fewer than 200 inscriptions, the corpus is slightly larger than that of Continental Elder Futhark (about 80 inscriptions, c. 400–700), but slightly smaller than that of the Scandinavian Elder Futhark (about 260 inscriptions, c. 200–800).

Runic finds in England cluster along the east coast with a few finds scattered further inland in Southern England. Frisian finds cluster in West Frisia. Looijenga (1997) lists 23 English (including two 7th-century Christian inscriptions) and 21 Frisian inscriptions predating the 9th century.

Currently known inscriptions in Anglo-Frisian runes include:

| FRISIAN |

| * Ferwerd combcase, 6th century; me uræ |

| * Amay comb, c. 600; eda |

| * Oostyn comb, 8th century; aib ka[m]bu / deda habuku (with a triple-barred h) |

| * Toornwerd comb, 8th century; kabu |

| * Skanomody solidus, 575–610; skanomodu |

| * Harlingen solidus, 575–625, hada (two ac runes, double-barred h) |

| * Schweindorf solidus, 575–625, wela[n]du "Weyland" (or þeladu; running right to left) |

| * Folkestone tremissis, c. 650; æniwulufu |

| * Midlum sceat, c. 750; æpa |

| * Rasquert swordhandle (whalebone handle of a symbolic sword), late 8th century; ek [u]mædit oka, "I, Oka, not made mad"[18] (compare ek unwodz from the Danish corpus) |

| * Arum sword, a yew-wood miniature sword, late 8th century; edæboda |

| * Westeremden A, a yew weaving-slay; adujislume[þ]jisuhidu |

| * Westeremden B, a yew-stick, 8th century; oph?nmuji?adaamluþ / :wimœ?ahþu?? / iwio?u?du?ale |

| * Britsum yew-stick; þkniaberetdud / ]n:bsrsdnu; the k has Younger Futhark shape and probably represents a vowel. |

| * Hantum whalebone plate; [.]:aha:k[; the reverse side is inscribed with Roman ABA. |

| * Bernsterburen whalebone staff, c. 800; tuda æwudu kius þu tuda |

| * Hamwic horse knucklebone, dated to between 650 and 1025; katæ (categorised as Frisian on linguistic grounds, from *kautōn "knucklebone") |

| * Wijnaldum B gold pendant, c. 600; hiwi |

| * Kantens combcase, early 5th century; li |

| * Hoogebeintum comb, c. 700; [...]nlu / ded |

| * Wijnaldum A antler piece; zwfuwizw[...] |

| ENGLISH |

| * Ash Gilton (Kent) gilt silver sword pommel, 6th century; [...]emsigimer[...][19] |

| * Chessel Down I (Isle of Wight), 6th century; [...]bwseeekkkaaa |

| * Chessel Down II (Isle of Wight) silver plate (attached to the scabbard mouthpiece of a ring-sword), early 6th century; æko:?ori |

| * Boarley (Kent) copper disc-brooch, c. 600; ærsil |

| * Harford (Norfolk) brooch, c. 650; luda:gibœtæsigilæ "Luda repaired the brooch" |

| * West Heslerton (North Yorkshire) copper cruciform brooch, early 6th century; neim |

| * Loveden Hill (Lincolnshire) urn; 5th to 6th century; reading uncertain, maybe sïþæbæd þiuw hlaw "the grave of Siþæbæd the maid" |

| * Spong Hill (Norfolk), three cremation urns, 5th century; decorated with identical runic stamps, reading alu (in Spiegelrunen). |

| * Kent II coins (some 30 items), 7th century; reading pada |

| * Kent III, IV silver sceattas, c. 600; reading æpa and epa |

| * Suffolk gold shillings (three items), c. 660; stamped with desaiona |

| * Caistor-by-Norwich astragalus, 5th century; possibly a Scandinavian import, in Elder Futhark transliteration reading raïhan "roe" |

| * Watchfield (Oxfordshire) copper fittings, 6th century; Elder Futhark reading hariboki:wusa (with a probably already fronted to æ) |

| * Wakerley (Northamptonshire) copper brooch, 6th century; buhui |

| * Dover (Kent) brooch, c. 600; þd bli / bkk |

| * Upper Thames Valley gold coins (four items), 620s; benu:tigoii; benu:+:tidi |

| * Willoughby-on-the-Wolds (Nottinghamshire) copper bowl, c. 600; a |

| * Cleatham (South Humbershire) copper bowl, c. 600; [...]edih |

| * Sandwich/Richborough (Kent) stone, 650 or earlier; [...]ahabu[...]i, perhaps *ræhæbul "stag" |

| * Whitby I (Yorkshire) jet spindle whorl; ueu |

| * Selsey (West Sussex) gold plates, 6th to 8th centuries; brnrn / anmu |

| * St. Cuthbert's coffin (Durham), dated to 698 |

| * Whitby II (Yorkshire) bone comb, 7th century; [dæ]us mæus godaluwalu dohelipæ cy[ i.e. deus meus, god aluwaldo, helpæ Cy... "my god, almighty god, help Cy…" (Cynewulf or a similar personal name; compare also names of God in Old English poetry.) |

| * the Franks casket; 7th century |

| * zoomorphic silver-gilt knife mount, discovered in the River Thames near Westminster Bridge (late 8th century)[20][21] |

| * the Ruthwell Cross; 8th century, the inscription may be partly a modern reconstruction |

| * the Brandon antler piece, wohs wildum deoræ an "[this] grew on a wild animal"; 9th century.[22] |

| * Kingmoor Ring |

| * the Seax of Beagnoth; 9th century (also known as the Thames scramasax); the only complete alphabet |

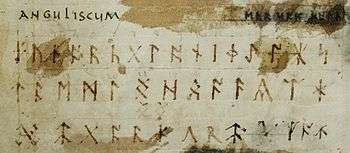

Related manuscript texts

- Codex Vindobonensis 795 — contains a description of Anglo-Saxon runes

- the Anglo-Saxon rune poem (Cotton Otho B.x.165)

- Cotton MS Domitian A IX

- The Byrhtferth's Manuscript MS 17 — contains a table of runic, cryptographic, and exotic alphabets

- Codex Sangallensis 878 — contains a presentation of Anglo-Saxon runes

- Solomon and Saturn (Nowell Codex) — contains some runes that stand for the word that names them

See also

| Part of a series on |

| Old English |

|---|

|

Dialects

|

|

History |

- Elder Futhark

- Ogham

- Old English Latin alphabet

- Runic alphabet

- Younger Futhark

Notes

- "Definition of FUTHORC". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "THE ANGLO-SAXON RUNES". arild-hauge.com.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1989), "Roman and Runic on St Cuthbert's Coffin", in Bonner, Gerald; Rollason, David; Stancliffe, Clare (eds.), St. Cuthbert, his Cult and his Community to AD 1200, Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, pp. 257–63, ISBN 978-0-85115-610-1.

- Osborn, Marijane (2010), Tir as Mars in the Old English Rune Poem, University of California, Davis: ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews.

- Osborn, Marijane (1980), A CELTIC INTRUDER IN THE OLD ENGLISH "RUNE POEM", Modern Language Society.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999), An introduction to English runes (2nd ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 41–42.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1998), Runes and Runic Inscriptions : Collected Essays On Anglo-Saxon and Viking Runes, Boydell, pp. 38, 53.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999), An introduction to English runes (2nd ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 45–47.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999), An introduction to English runes (2nd ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 41–42.

- Hines, John (2011), Anglia - Zeitschrift fr englische Philologie, Volume 129, Issue 3-4, pp. 288–289.

- Waxenberger, Gaby (2017), Anglia - Zeitschrift fr englische Philologie, Volume 135, Issue 4, pp. 627–640.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999), An introduction to English runes (2nd ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 139, 155.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999), An introduction to English runes (2nd ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 186–199.

- Kilpatrick, Kelly (2013), Latin, Runes and Pseudo-Ogham: The Enigma of the Hackness Stone, pp. 1–13.

- Birkett, Thomas (2012), Notes and Queries, Volume 59, Issue 4, Boydell, pp. 465–470.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999), An introduction to English runes (2nd ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 111–112.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999), An introduction to English runes (2nd ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell, pp. 93, 112–113.

- Looijenga, Tineke (1 January 2003). Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions. google.be. ISBN 978-9004123960.

- Flickr (photograms), Yahoo!

- "Silver knife mount with runic inscription", British Museum.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999), An introduction to English runes (2nd ed.), Woodbridge: Boydell, p. 182.

- Bammesberger, Alfred (2002), "The Brandon Antler Runic Inscription", Neophilologus, Ingenta connect, 86: 129–31, doi:10.1023/A:1012922118629.

References

- Bammesberger, A, ed. (1991), "Old English Runes and their Continental Background", Anglistische Forschungen, Heidelberg, 217.

- ——— (2006), "Das Futhark und seine Weiterentwicklung in der anglo-friesischen Überlieferung", in Bammesberger, A; Waxenberger (eds.), Das fuþark und seine einzelsprachlichen Weiterentwicklungen, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 171–87, ISBN 978-3-11-019008-3.

- Hines, J (1990), "The Runic Inscriptions of Early Anglo-Saxon England", in Bammesberger, A (ed.), Britain 400–600: Language and History, Heidelberg, pp. 437–56.

- Kilpatrick, K (2013), Latin, Runes and Pseudo-Ogham: The Enigma of the Hackness Stone, pp. 1–13

- J. H. Looijenga, Runes around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150–700, dissertation, Groningen University (1997).

- Odenstedt, Bengt, On the Origin and Early History of the Runic Script, Uppsala (1990), ISBN 91-85352-20-9; chapter 20: 'The position of continental and Anglo-Frisian runic forms in the history of the older futhark '

- Page, Raymond Ian (1999). An Introduction to English Runes. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-768-9.

- Middleton & Tum, Andrew & Julia (2006). Radiography of Cultural Material. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7506-6347-2.

- Robinson, Orrin W (1992). Old English and its Closest Relatives: A Survey of the Earliest Germanic Languages. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1454-9.

- Frisian runes and neighbouring traditions, Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 45 (1996).

- H. Marquardt, Die Runeninschriften der Britischen Inseln (Bibliographie der Runeninschriften nach Fundorten, Bd. I), Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Phil.-hist. Klasse, dritte Folge, Nr. 48, Göttingen 1961, pp. 10–16.

Further reading

- Looijenga, Tineke (September 2003). Texts & Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions (Northern World, 4). Brill. ISBN 978-9004123960.