Man

A man is an adult male human. Prior to adulthood, a male human is referred to as a boy.

.jpg)

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Masculism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

Topics and issues

|

||||

|

By country

|

||||

|

Lists and categories

|

||||

|

See also |

||||

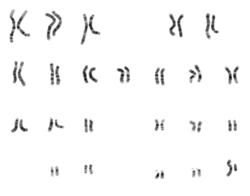

Like most other male mammals, a man's genome typically inherits an X chromosome from his mother and a Y chromosome from his father. The male fetus generally produces larger amounts of androgens and smaller amounts of estrogens than a female fetus. This difference in the relative amounts of these sex steroids is largely responsible for the physiological differences that distinguish men from women. During puberty, hormones which stimulate androgen production result in the development of secondary sexual characteristics, thus exhibiting greater differences between the sexes. However, there are exceptions to the above for some transgender and intersex men.

Etymology and terminology

The English term "man" is derived from a Proto-Indo-European root *man- (see Sanskrit/Avestan manu-, Slavic mǫž "man, male").[1] More directly, the word derives from Old English mann. The Old English form had a default meaning of "adult male" (which was the exclusive meaning of wer), though it could also signify a person of unspecified gender. The closely related Old English pronoun man was used just as it is in Modern German to designate "one" (e. g., in the saying man muss mit den Wölfen heulen).[2]

Biology

In human beings, the sex of an individual is determined at the time of fertilization by the genetic material carried in the sperm cell. If a sperm cell carrying an X chromosome fertilizes the egg, the offspring will typically be female (XX). On the other hand, if a sperm cell carrying a Y chromosome fertilizes the egg, the offspring will typically be male (XY). Persons whose anatomy or chromosomal makeup differ from this pattern are referred to as intersex.

Like most other male mammals, a man's genome typically inherits an X chromosome from his mother and a Y chromosome from his father. The male fetus produces larger amounts of androgens and smaller amounts of estrogens than a female fetus. This difference in the relative amounts of these sex steroids is largely responsible for the physiological differences that distinguish men from women.

Humans exhibit sexual dimorphism in many characteristics, many of which have no direct link to reproductive ability, although most of these characteristics do have a role in sexual attraction. Most expressions of sexual dimorphism in humans are found in height, weight, and body structure, though there are always examples that do not follow the overall pattern. For example, men tend to be taller than women, but there are many people of both sexes who are in the mid-height range for the species.

Primary sex characteristics (or sex organs) are characteristics that are present at birth and are integral to the reproductive process. For men, primary sex characteristics include the penis and testicles. Secondary sex characteristics are features that appear during puberty in humans.[3][4] Such features are especially evident in the sexually dimorphic phenotypic traits that distinguish between the sexes, but—unlike the primary sex characteristics—are not directly part of the reproductive system.[5][6][7] Secondary sexual characteristics that are specific to men include:

- Facial hair;[6]

- Chest hair;[8]

- Broadened shoulders;[9]

- An enlarged larynx (also known as an Adam's apple);[9] and

- A voice that is significantly deeper than the voice of a child or a woman.[6]

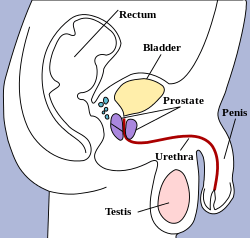

Reproductive system

The male reproductive system includes external and internal genitalia. The male external genitalia consist of the penis, the male urethra, and the scrotum, while the male internal genitalia consist of the testes, the prostate, the epididymis, the seminal vesicle, the vas deferens, the ejaculatory duct, and the bulbourethral gland.[10]

The male reproductive system's function is to produce semen, which carries sperm and thus genetic information that can unite with an egg within a woman. Since sperm that enters a woman's uterus and then fallopian tubes goes on to fertilize an egg which develops into a fetus or child, the male reproductive system plays no necessary role during the gestation. The study of male reproduction and associated organs is called andrology.

Sex hormones

In mammals, the hormones that influence sexual differentiation and development are androgens (mainly testosterone), which stimulate later development of the ovary. In the sexually undifferentiated embryo, testosterone stimulates the development of the Wolffian ducts, the penis, and closure of the labioscrotal folds into the scrotum. Another significant hormone in sexual differentiation is the anti-Müllerian hormone, which inhibits the development of the Müllerian ducts. For males during puberty, testosterone, along with gonadotropins released by the pituitary gland, stimulates spermatogenesis.

Sexuality and gender

Male sexuality and attraction vary from person to person, and a man's sexual behavior can be affected by many factors, including evolved predispostions, personality, upbringing, and culture. While the majority of men are heterosexual, significant minorities are homosexual or bisexual.[13] Some men identify as mostly straight.[14]

A small percentage of people assigned female at birth may identify as male (typically referred to as transgender men). In contrast, some people assigned male at birth may identify as female (typically referred to as transgender woman). Some people assigned male at birth may also identify as non-binary.[15] There are also intersex people who may identify as either female or male.

Masculinity

Masculinity (also sometimes called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles associated with boys and men. Although masculinity is socially constructed,[16] some research indicates that some behaviors considered masculine are biologically influenced.[17] To what extent masculinity is biologically or socially influenced is subject to debate.[17] It is distinct from the definition of the biological male sex, as both males and females can exhibit masculine traits.[18]

Standards of manliness or masculinity vary across different cultures and historical periods.[19] While the outward signs of masculinity look different in different cultures, there are some common aspects to its definition across cultures. In all cultures in the past, and still among traditional and non-Western cultures, getting married is the most common and definitive distinction between boyhood and manhood.[20] In the late 20th century, some qualities traditionally associated with marriage (such as the "triple Ps" of protecting, providing, and procreating) were still considered signs of having achieved manhood.[20][21]

Anthropology has shown that masculinity itself has social status, just like wealth, race and social class. In Western culture, for example, greater masculinity usually brings greater social status. Many English words such as virtue and virile (from the Indo-European root vir meaning man) reflect this.[22][23]

The Parsons model was used to contrast and illustrate extreme positions on gender roles. Model A describes total separation of male and female roles, while Model B describes the complete dissolution of barriers between gender roles.[24]

See also

Medical:

- Sex assignment

- Men's health

- Gender differences

Dynamics:

Political:

- Men's studies

- Masculism

- Men's Rights

References

- American Heritage Dictionary, Appendix I: Indo-European Roots. man-1 Archived 19 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2007-07-22.

- John Richard Clark Hall: A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM (2011). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1054. ISBN 1437736009.

- Pack PE (2016). CliffsNotes AP Biology, 5th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 219. ISBN 0544784170.

- Bjorklund DF, Blasi CH (2011). Child and Adolescent Development: An Integrated Approach. Cengage Learning. pp. 152–153. ISBN 113316837X.

- "Primary & Secondary Sexual Characteristics". Sciencing.com. 30 April 2018.

- Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Elsevier Science. 2018. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-12-815145-7.

- "Secondary sexual characteristics". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- Berger, Kathleen Stassen (2005). The Developing Person Through the Life Span. Worth Publishers. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-7167-5706-1.

- "Definition of Male genitalia". MedicineNet.

- "Why is life expectancy longer for women than it is for men?". Scientific American. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Walton, Alice G. "The Gender Inequality of Suicide: Why Are Men at Such High Risk?". Forbes. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Bailey, J. Michael; Vasey, Paul; Diamond, Lisa; Breedlove, S. Marc; Vilain, Eric; Epprecht, Marc (2016). "Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science". Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 17 (2): 45–101. doi:10.1177/1529100616637616. PMID 27113562.

- Savin-Williams, Ritch C. (2017). Mostly Straight: Sexual Fluidity among Men. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-98104-1.

- Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression in Social Work Practice, edited by Deana F. Morrow and Lori Messinger (2006, ISBN 0-231-50186-2

- Shehan, Constance L. (2018). Gale Researcher Guide for: The Continuing Significance of Gender. Gale, Cengage Learning. pp. 1–5. ISBN 9781535861175.

- Social vs biological citations:

- Shehan, Constance L. (2018). Gale Researcher Guide for: The Continuing Significance of Gender. Gale, Cengage Learning. pp. 1–5. ISBN 9781535861175.

- Martin, Hale; Finn, Stephen E. (2010). Masculinity and Femininity in the MMPI-2 and MMPI-A. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-0-8166-2444-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lippa, Richard A. (2005). Gender, Nature, and Nurture (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 153–154, 218–225. ISBN 9781135604257.

- Wharton, Amy S. (2005). The Sociology of Gender: An Introduction to Theory and Research. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-1-40-514343-1.

- Male vs Masculine/Feminine:

- Ferrante, Joan (January 2010). Sociology: A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 269–272. ISBN 978-0-8400-3204-1.

- "What do we mean by 'sex' and 'gender'?". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014.

- Halberstam, Judith (2004). "'Female masculinity'". In Kimmel, Michael S.; Aronson, Amy (eds.). Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 294–5. ISBN 978-1-57-607774-0.

- Kimmel, Michael S.; Aronson, Amy, eds. (2004). Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-1-57-607774-0.

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen (1998). "Learning to Stand Alone: The Contemporary American Transition to Adulthood in Cultural and Historical Context". Human Development. 41 (5–6): 295–315. doi:10.1159/000022591. ISSN 0018-716X.

- Gilmore, David D. (1990). Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity. Yale University Press. pp. 48. ISBN 0-300-05076-3.

- "Virtue (2009)". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "Virile (2009)". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- Brockhaus: Enzyklopädie der Psychologie, 2001.

Further reading

- Andrew Perchuk, Simon Watney, bell hooks, The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation, MIT Press 1995

- Pierre Bourdieu, Masculine Domination, Paperback Edition, Stanford University Press 2001

- Robert W. Connell, Masculinities, Cambridge : Polity Press, 1995

- Warren Farrell, The Myth of Male Power Berkley Trade, 1993 ISBN 0-425-18144-8

- Michael Kimmel (ed.), Robert W. Connell (ed.), Jeff Hearn (ed.), Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities, Sage Publications 2004