Anglo-Saxon dress

Anglo-Saxon dress refers to the clothing and accessories worn by the Anglo-Saxons from the middle of the 5th century through the eleventh century. Archaeological finds in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries have provided the best source of information on Anglo-Saxon costume. It is possible to reconstruct Anglo-Saxon dress using archaeological evidence combined with Anglo-Saxon and European art, writing and literature of the time period. Archaeological finds have both supported and contradicted the characteristic Anglo-Saxon costume as illustrated and described by these contemporary sources.

The collective evidence of cemetery grave-goods indicates that men's and women's costume was not alike. Women's dress changed frequently from century to century, while men's dress changed very little. Women typically wore jewellery, men wore little or no jewellery. The beginning of the seventh century marked the conversion of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to Christianity. Religious art, symbols and writings from the conversion years greatly influenced costume fashion from this period onward, especially's women's dress and jewellery. Historical research has shown that Anglo-Saxon children wore smaller versions of adult garments.

Clothing worn by the military, the elite class and religious orders was initially similar to the daily garments of the common man and woman. Over time, and with the influence of European culture, the spread of Christianity and the increasing prosperity of Anglo-Saxon England, garments and accessories specific to each group became the standard by which they were identified.

During the Anglo-Saxon era, textiles were created from natural materials: wool from sheep, linen from flax and imported silk. In the fifth and sixth centuries, women were the manufacturers of Anglo-Saxon clothing, weaving textiles on looms in their individual dwellings. In the seventh thru the ninth centuries, Anglo-Saxon communities changed slowly from primarily small settlements to a mix of small and large settlements, and large estates. Specialized workshops on large landholdings were responsible for the manufacture of textiles and clothing for the estate community. In the tenth and eleventh centuries, the growth of urban centers throughout England expanded the variety and quantity of textiles, clothing, and accessories that were made available to the public and also changed the way in which clothing and accessories were manufactured.

Overview: Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon timeline

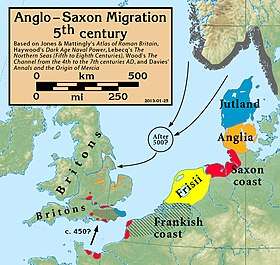

The end of Roman rule in Britain led to the withdrawal of the Roman armies in the late fourth and early fifth century.[1] By the mid-fifth century, an influx of Germanic peoples arrived in England, many leaving overcrowded native lands in Northwestern Europe and others fleeing rising sea levels on the North Sea coast.[2] The middle of the fifth century marked the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon era in England.[3]

The Anglo-Saxon era consists of three different time periods: The early Anglo-Saxon era, which spans the mid-fifth to the beginning of the seventh century; the middle Anglo-Saxon era, which covers the seventh thru the ninth centuries; and the late Anglo-Saxon era, which includes the tenth and eleventh centuries.[4]

Anglo-Saxon identity

In Anglo-Saxon England, clothing and accessories were used to establish identity of gender, age, ethnicity, regionality, occupation and status. Initially, the early migrants to England displayed their Germanic identity through their choices in clothing and accessories. Later, Anglo-Saxon dress was shaped by European costume styles, as well as European art and religious emblems of Christianity. A person's identity as a believer in Christianity was manifested through dress. Cross-shaped designs appear on Kentish disc brooches as early as the late sixth century. Tiny crosses also start appearing on shoulder clasps and on Kentish belt buckles in the seventh century.[5] Clothing and accessories varied from the functional, the recycled, the symbolic, the elegant, the opulent and the elaborate. Commoners typically possessed one main garment, which they wore daily. Their clothes were often recycled from older, out-of-style clothing and handed-down items. Higher-status individuals typically owned multiple items of clothing and accessories, often made with high-quality and expensive materials, and decorated in intricate detail.[6][7]

The archaeological record

.jpg)

Archaeological finds in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries have provided the best source of information on Anglo-Saxon dress. Pagan burial practices in the early Anglo-Saxon era included placing grave-goods with the clothed body. Archaeological excavations from this era have provided a rich supply of artefacts that have been analysed and compared to contemporary Anglo-Saxon and European art, writing and literature in order to reconstruct a standard Anglo-Saxon costume. Archaeological evidence for female burials is abundant in the fifth and the sixth centuries. The cemetery evidence for male burials is limited compared to female burials, with primarily belt buckles and other belt fittings and a few pins.[5]

The beginning of the seventh century marked the decline of the pagan tradition of including grave-goods in burials. This change in funerary practice coincided with the Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England. Beginning in the eighth century, grave-goods, except for simple items like knives and belts, were no longer included with individual burials. This lack of costume artefacts makes it more challenging for historians and archaeologists to determine what Anglo-Saxons were wearing during the eighth thru the eleventh centuries.[8]

Archaeological evidence from Anglo-Saxon cemeteries have alternately supported and contradicted contemporary illustrations of Anglo-Saxon costume. For example, there are burial finds of finger rings, some engraved with names, in both male and female graves; finger rings never appear in Anglo-Saxon illustrations. Alternately, the penannular brooch, arm-rings and neck-rings that show up occasionally in Anglo-Saxon art are not supported by any finds from Anglo-Saxon cemetery excavations.[8]

Women's costume

Fifth to sixth centuries

Fifth and sixth century women's costume has been reconstructed by scholars, based on the archaeological evidence of brooches worn in pairs at the shoulders. Researchers continue to fill current gaps of knowledge about female dress during this time period. The female gown is presumed to be ankle-length (women in Anglo-Saxon art and later in medieval art are usually represented in long garments). Currently, there is no archaeological evidence to support this belief. Experiments to recreate early Anglo-Saxon female dress have resulted in the creation of a female costume which includes a long under-gown, with a buckled belt which holds suspended items including knives, keys, amulets, and weaving tools. The long gown is covered with a short peplos, which could be easily hitched up to reach the tools.[3][9]

The age of a woman often designated the costume that would be her daily dress.[10] Dress and accessories, specifically the peplos, the pin, a belt or girdle with tools and keys, was relevant to a woman's age and state of life, especially to the child-bearing years and marriage. The peplos was typically worn starting in the teen years and continually worn until a woman was in her forties, past childbearing age.[11] This long garment, with its paired shoulder brooches, was a comfortable garment for breastfeeding and could expand easily when a woman was pregnant. Though most finds are long, it has sometimes been interpreted as possible to wear a short one.[12] Although the peplos was traditionally worn starting in the teens, archaeological evidence indicates that girls as young as eight years old, wore the peplos, but marked their younger age by fastening their gowns with one brooch instead of two.[13]

Beginning in the fifth century, women in Kent wore a slightly different costume, influenced by fashions from the Frankish Empire, than women from other regions of Anglo-Saxon England. The costume consisted of a front-fastening garment and a Frankish-inspired front-fastening jacket, which was attached by four brooches. In the last third of the sixth century in Kent, women's dresses were fastened by an ornate disk brooch at the throat, replacing "the coat-based costume fastened by four brooches in two matched pair sets down the length of the coat."[14] There were other regional variations of women's dress, notably in Anglian areas, where wrist clasps and a third, central brooch and distinctive 'girdle-hangers' were the norm. Women's costume throughout England was enhanced by beads made of glass, paste and amber and less frequently, crystal. Garlands of beads were typically suspended between the shoulder brooches, and other bead clusters often hung from brooches, attached to girdles and were sometimes worn on their own.[5] [15]

Main garment

The typical women's costume of this era was a long peplos-like garment, pulled up to the armpit and worn over a sleeved under-garment, usually another dress. The garment was clasped front to back by fastening brooches at the shoulders.[16] Anglo-Saxon women in this period may or may not have worn a head covering.[17] The dress could be belted or girdled, and easily adjusted to changes in the woman's weight. It is unknown what the Anglo-Saxons called the peplos-style gown.[18]

Linen or wool could be used to make the peplos garment. There has been discussion among historians of whether a preference of one fibre over the other was a matter of fashion changes over time or related to regional differences. Fashion changes tended to begin in eastern England, reflecting contemporary fashion styles in Europe, and those changes would move slowly over time to the West Saxon region.[5][19]

Survival of fur is rare in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries. It is likely that fleeces and furs were used as garment lining or as warm outer garments. Anglo-Saxon textile and clothing historian, Penelope Walton-Rogers, has recently identified buckled capes of animal pelt that were found in Anglo-Saxon women's graves. A simple poncho made with a neck-opening for the head could have been made from skins of domesticated sheep or cattle. Literary evidence confirms the use of fur garments, primarily in the late Anglo-Saxon period.[20]

Accessories

Evidence of footwear from early Anglo-Saxon graves is rare until the late sixth and seventh centuries.[21] Agricultural labourers shown ploughing and sowing in Anglo-Saxon illustrated manuscripts work barefoot, which may indicate that footwear was not the norm until the middle Anglo-Saxon era.[22] Clothing fasteners made of organic material are rare finds, although archaeological evidence from urban settlements has shown that Anglo-Saxons were skilled at working organic material, including bone, horn, antler and wood. Evidence shows that the skin of cattle, deer, goat, pig and sheep were used to make leather goods. Although only tiny remnants of leather survive, they are usually attached to buckles and to wrist clasps. Leather was probably used to make belts, suspension straps, and cuffs, although cloth was also used to make those items.[4]

Seventh to ninth centuries

Along with the spread of Christianity in seventh century England, religious art and European fashion inspired changes in women's dress.[14] These changes were marked by the disappearance of the paired brooch, aside from very small annular and penannular brooches; occasional elaborate, round brooches were also worn individually. Linked pins appeared during the seventh century. There were fewer bead ornaments than before, and amber largely disappeared during this time period.[23]

Main garment

Changes in Anglo-Saxon women's dress began in the latter half of the sixth century in Kent and spread to other regions at the beginning of the seventh century. These fashion changes show the decreasing influence of Northern Europe and the increasing influence of the Frankish Kingdom and the Byzantine Empire and a revival of Roman culture. Linen is used more widely for garments and under-garments. Although there is little evidence to show whether women wore leggings or stockings under their gowns, it more than likely that these leg-covering were worn, as men typically wore stocking and leggings during this period.[24]

Accessories

During this period, women's jewellery, besides brooches used to fasten clothing, consisted of simple neck ornaments of small glass beads or strands of beads hung on metal rings, strung from shoulder to shoulder over garments. This fashion remained in place until the late seventh century. This era is noticeable for the decline of the paired brooch fashion. Amethyst beads started appearing at this time, along with necklaces of gold and silver wire, and, as a symbol of being Christian, small jewelled crosses. Occasionally, elaborate, round brooches were worn at the throat. Linked pins were now appearing among grave-goods. There were fewer bead ornaments than before, and amber was no longer used.[25][26]

Tenth and eleventh centuries

In the tenth and eleventh centuries, the growth of cities throughout England expanded the variety and quantity of textiles, clothing, and accessories that were made available to Anglo-Saxon women. Textiles and accessories could be mass-produced making these items more affordable. For more affluent women, finer materials and more opulent clothing and jewellery were easily obtainable.

Overgarment

Many names for cloak appear during this time period, including basing, hacele, mentel and rift. A symmetrical cloak draped around the shoulders and fastened with a brooch is fashionable in this period, but is declining in popularity. Hooded cloaks attached by a circular brooch are described in the literature of this time period.[27]

Main garment

Women wearing a sleeveless overgarment, with or without hood, can be seen in artistic representations of this time period. Women in late Anglo-Saxon art are depicted wearing hooded garments: either a scarf wrapped around the head and neck or an unconnected head covering with an opening for the face. It was assumed that the hooded style was influenced by Near Eastern art.[28] Women are shown wearing ankle-length, tailored gowns. Gowns are often depicted with a distinct border, sometimes in a contrasting colour. In the tenth century, women's arms are typically covered. Sleeves are seen as straight, with a slight flair at the end. Braided or embroidered borders often decorated sleeves. By the eleventh century, multiple sleeve styles had come into fashion.[29]

There is little evidence to show whether women wore leggings or stockings under their gowns in the tenth and the eleventh centuries, although it probable that these clothing items were worn, as men typically wore stocking and leggings during this period.[24]

Accessories

The girdles and buckled belts that were popular in the fifth and sixth century, with tools and personal items suspended from the belt, have gone out of fashion by the tenth century.[30]

In the art of this period, women wear simple ankle shoes and slippers, usually black in colour, but with a contrasting strip of colour on the top of the shoe. Archaeological finds of this period demonstrate that a variety of women's shoe styles were being worn.[31]

Men's costume

Anglo-Saxon burial excavations have uncovered little evidence of what men wore during this period. Weapons were often buried with men, but dress accessories were less likely to be found except for belt buckles. The lack of fasteners and brooches in male graves resulted in few textile remnants of men's clothing. The few textile fragments that have been found, fortunately were found in good condition for analysis.[32]

To reconstruct men's costume from the Anglo-Saxon period, a review can be made of the writing, art and archaeological finds in north-western Europe and Scandinavia from previous centuries and during the Anglo-Saxon era. Romans in the second century described the use of fur and skin garments among the Germanic tribes. With the introduction of the warp-weighted loom in (c. 200 AD), wool clothing would have been available for men and may have replaced or diminished the reliance and fur and skin garments.[33]

Fifth to sixth centuries

Overgarment

Anglo-Saxon men of 5th and 6th century England dressed alike regardless of social rank. The fashions during this time consisted of the cloak, tunic, trousers, leggings, and accessories. Short textile-made cloaks are seen on Roman sculptures of Germanic captives. It has been determined that cloaks were composed of cloth and clasped on one shoulder. Men wearing similarly styled cloaks, clasped with circular brooches, occur in late era Anglo-Saxon drawings and paintings. It is probable that this style of clothing was worn by Germanic tribes on the continent and later when they migrated to England. Male burial artefacts from the fifth to the seventh centuries rarely include brooches; any metalwork uncovered have usually been pins found in the chest area of the body. It is likely that men in this period used brooches made of perishable material, secured their cloaks with leather or cloth laces, covered themselves with cloaks without using clasps, or used poncho-style cloaks.[34]

Because of the lack of Anglo-Saxon male burial finds, archaeologist have looked to earlier period writings from Europe and earlier century finds from Scandinavian peat bogs to predict what Anglo-Saxon men might have worn. It is probable that a short, fur-lined cloak was used with the skin of the animal faced outward and the fur brushed against the undergarments.[35][36]

Main garment

Roman writers and sculpture of Germanic men depict knee-length or shorter tunics with either short or long sleeves. Clasps were not needed to hold the tunic together because when pulled over the head it would sit snugly around the neck without the use of lacing or ties, indicating that the garment was one continuous piece. A belt or girdle was usually worn with the tunic and might have had a buckle, and, as Anglo-Saxon historian, Gale Owen-Crocker states, "pouched over the belt".[37]

Historians are reasonably confident that Anglo-Saxon men wore trousers. The Roman poet Ovid described the wearing of trousers by Germanic barbarians. Ankle-length trousers are also seen on Roman sculptures of Germanic men, often with a short tunic, tied around the waist with a belt or draped with a cloak. It is probable that Anglo-Saxon men wore either baggy or narrow trousers, belted at the waist and possibly attached to the legs with either garters or leggings. If loose, the excess material was bunched around the waist and, as Owen-Crocker describes, "hung in folds around the legs". Garters or leggings probably accompanied narrow trousers.[38]

Leggings and footwear

Leg-garments, or leggings were usually worn in pairs; these items served as additional protection for the legs. Linguistic documents from this era reveal that early Anglo-Saxon males wore two types of leg-garments. The first type of leggings would have been a leather or cloth stocking; the second type was most likely cloth strips or wool tied around the leg. Binding strips to the legs had the added benefit of being able to wind the cloth around or cover the foot for extra warmth and protection.[39]

Footwear has not been found in Anglo-Saxon graveyards in the fifth to sixth centuries. It is likely that Anglo-Saxons, especially agricultural labourers, went barefoot, although linguistic documentation has revealed that there were several shoe types in circulation during this time period: slippers, raw-hide pampooties and pouch-like foot coverings. Anglo-Saxons most likely covered their bare feet, except when working. Shoes presumably would have been made of leather and secured with straps. Hats and hoods were commonly worn, as were gloves and mittens.[40]

Accessories

The only male accessory frequently found in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries is belt hardware. Men's belt hardware tended to be more elaborate than women's belt hardware. Leather remnants have been discovered in male graves attached to buckles, which makes it more than likely that leather belts were a common clothing accessory. Men usually carried a knife, other tools, and sometimes amulets at the waist.[41]

Jewellery was found in very few male graves of this period. Some beads have been uncovered in some male burial sites and may have been decorated a belt or weapon. Anglo-Saxon literary evidence from this time period suggest that men frequently wore rings, but there have been very few rings discovered in Anglo-Saxon male graves.[42]

Seventh to ninth centuries

This era marked the disappearance of furnished graves, but also saw the installation of some of the wealthiest male burials of the Anglo-Saxon era. The best example is the Sutton Hoo ship burial, which is dated to the early 7th century. It has been determined to be the burial of a king.[43][44]

Writings of an eighth century historian, Paulus Catena, describe Germanic peoples inhabiting the Italian Peninsula during this time period, "Indeed their clothes were roomy and especially linen, as the Anglo-Saxons were accustomed to have, embellished with rather wide borders woven in various colours" Paulus's description of Anglo-Saxon wearing linen is confirmed by eighth century writers, Bede and Aldhelm. Linen was likely the favoured fabric over wool for garments worn in eighth century Anglo-Saxon England.[45]

There are several clothing references in seventh and eighth century letters. Letters between King Offa of Mercia and the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne demonstrate that clothing in Anglo-Saxon England was similar to Carolignian Frankia. This costume has been described as a short tunic over linen shirt and linen drawers with long stockings. In winter, a cloak was worn over the costume.[46]

Overgarment

Cloak of this period, included the cloak style seen on the Franks Casket, made with rectangular cloth, and fastened so the cloak appeared to be pleated or folded, and held together at the right shoulder with a brooch. Once in place, the brooch was left attached to the garment so that the cloak was slipped over the head.[47] Ninth century art shows a few different styles of cloak: hooded, non-hooded with a frilled collar, and the pleated cloaks arranged over the shoulders and bound at the waist by a belt. These belts were narrower than earlier in the Saxon period, with fewer tools hanging from them. The wrap-over coat made an appearance during this era. This knee-length coat wrapped over the front of the body. Its sleeves were, as Owen-Crocker says, "deep, [with] decorated cuffs which [were] mostly straight". The cloaks of common men were simple and less decorated than cloaks of wealthier men.[48]

Main garment

Human figures start to appear in art during this period. Most of the male figures displayed in Anglo-Saxon art wear short, above-the-knee, girdled tunics. Short tunics were most commonly worn, but longer tunics are seen on Anglo-Saxon sculpture. Eighth century writer Aldhelm describes a linen shirt worn under a tunic. Other contemporary writings describe the use of undergarments. It is possible that loin cloths were used as undergarment or on its own if a tunic was not worn.[49]

Trousers continued to be worn by men. Traditionally worn under a short tunic or with a small cloak, they were typically ankle length. The jacket appeared during this time as well. For those who could afford it, the jacket was made of fur while less costly ones were made of linen. This jacket was waist-length and tended to have a broad collar.[50]

Leggings and footwear

Leggings and stockings continued to be worn in the seventh through to the ninth centuries. Frankish fashion for elaborate gartering was very popular in the seventh century.[51]

From the beginning of the seventh century, shoes become more abundant as burial artefacts. A burial site at Banstead Downs uncovered a male skeleton with soft leather ankle-boots which included eyelets for leather thongs. This boot style is similar to archaeological finds for the same period in York.[52]

Accessories and jewellery

Archaeological finds indicate that the belt continued to be used in Anglo-Saxon male costume in the seventh through to the ninth centuries. Knives were often suspended from belts and in the early seventh century, leather sheaves started to appear with knives. Leather and fabric pouches make their initial appearance during this time period. Many of the buckles were simple and small, although more elaborate and opulent buckles have been discovered. Kent burials include a number of large, triangular belt buckles from male graves. The conversion of Anglo-Saxon England to Christianity is demonstrated in the appearance of buckles with the cross symbols and fish emblem. As seen on the St. Mary Bishophill sculpture in York of two Anglo-Saxon men, horns could be suspended from the belt.[53][54]

Brooches have been rare in archaeological finds for this period, but it is probable that disc-headed pins and other pins were worn by men as they have been found in Anglo-Saxon settlements. The quoit brooch is a very early type. Disc brooches such as the Harford Farm Brooch appear in Anglo-Saxon art at the beginning of the seventh century, but have not been discovered as archaeological finds in male graves. At the beginning of the ninth century, gold was scarce, and was rarely found on brooches. Brooches were typically created with base metal or silver; the Fuller Brooch and Strickland Brooch are both in silver, as is the Anglo-Scandinavian Ædwen's brooch. The ninth century initiated elaborate finger-rings into Anglo-Saxon fashion.[55]

Gloves were commonly used in Anglo-Saxon England by the beginning of the eighth century. Falconers wore gloves and depictions of gloves have been found on Anglo-Saxon sculpture. Archaeological evidence has shown that elaborate gloves made with fine material have been found in Europe. This quality and styling of gloves could have easily migrated to England.[56]

Tenth and eleventh centuries

The literary, linguistic and artistic evidence of the tenth and eleventh centuries reveals many examples of male fashion. There are a variety of costumes depicted, shorter garments for the average male and longer garments for elite individuals. Different occupations and functions, like farming, hunting, and soldiering required different styles of clothing.[57]

Overgarment

Cloaks were worn indoors and outdoors and covered both short and long garments. Cloaks were rectangular or square in shape, attached with a brooch and not usually tailored. Circular brooches were the most common style brooches used by men at this time.[58]

Main garment

The short tunic continues to be the standard garment of Anglo-Saxon men. They were usually knee-length, but sometimes worn at a shorter length. The tunic continues to be bound at the waist by a belt or girdle. It is most likely that the tunic fabric was joined at the sides, and the neck opening was probably tied by string, ribbon or cloth. Sleeves were believed to be either short or long, with longer sleeves more likely acting as an undergarment. Undergarments continue to be worn and are more detailed in decoration. Linen shirts or a garment similar to a nightgown could be worn under the main garment.[59]

Leggings and footwear

Art from this period, including the Bayeux Tapestry indicate that men continued to wear leggings and stockings. Leg coverings often cover the shoes and probably covered the foot. The material was likely made of woven cloth as knitting would not be introduced in England until the sixteenth century.[60][61]

Excavations in late Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Viking London, Winchester and York has produced many shoes: flat-soled, leather 'turn shoes' (made inside out and then turned), and thonged shoes. The most common type of shoe is the ankle-high shoe, but lower slippers and taller boots also have been found. Flat, black shoes with a white stripe on top are the typical male footwear seen in Anglo-Saxon art during this time period.[62]

Accessories and jewellery

Knives, suspended from belts and girdles, no longer appear in Anglo-Saxon art of this period[63]

Brooches of the tenth and eleventh centuries are typically circular.[8] The most opulent brooches are silver, others are base metal. Small, round brooches, worn as cloak fasteners, are often depicted on men in late Anglo-Saxon art. Other brooch types which have been uncovered in late Anglo-Saxon burial finds are not seen in Anglo-Saxon art during this time period.[64]

Children's costume

Grave-goods identified as belonging to children are scarce in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries. The little evidence suggests that children wore clothing that was similar to adults.[65] Children's artefacts that have been found, include wrist and ankle bangles, neck-rings, small knives and beads. The most common accessory found in children's graves is the bead, worn individually or in small numbers. Both boys and girls could be buried with a belt buckle, although buckles were not typically worn until adulthood.[66] Children's and adult's clothing show differences in the type of clothing material worn. A higher percentage of linen is found in children's graves compared to adult burials. Linen may have been preferable for children's garments, since it was much easier to wash repeatedly than wool.[67]

Illustrations and paintings from the sixth to eleventh centuries in England, always depict male children. They are usually seen in short tunics with shirts. Infants are portrayed in long gowns, and either wear no head covering or wear head covering similar to women of the period.[68]

Dress and status

The wealth of an Anglo-Saxon could be measured by the number and variety of garments, accessories, and jewellery he or she possessed and the quality of those items.[69] Status in jewellery is reflected in size, intricacy, and use of gold, silver and garnet. Wealthier men and women owned footwear in the early Anglo-Saxon era, a period when many Anglo-Saxons were probably going barefoot. The affluent often had newer clothing and wore the latest fashions in clothing and accessories.[70][71]

Documentary evidence has shown that luxurious textiles were abundant in Anglo-Saxon England. These materials included imported silks, and textiles and clothing embroidered with gold. Most of these extravagant items were primarily used as religious garments, but it is also highly likely that royals and the wealthier members of Anglo-Saxon society owned opulent and expensive clothing.[44] [71]

Fifth to seventh centuries

Prosperity was marked by ownership of gold: buckles, brooches and gold embroidery or brocading on garments. Ornate buckles and clasps identified the wearer as important men of the seventh century. The jacket appeared during this time as well. For those who could afford it, the jacket was made of fur while less costly ones were made of linen.[72] Pile woven cloaks, which probably imitated fur in their shaggy effect, were a high status alternative for men in the seventh century.[73] The extremely affluent male buried AD 625 in the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial (mound 1) was supplied with two pairs of shoes, several yellow-dyed cloaks, and possible alternative sets of jewelled belt equipment.[23][74]

"The Sutton Hoo Mound 1 warrior can be characterized as equipped in the manner of a Roman general....His helmet is modelled ultimately on a fourth-century Roman cavalry parade helmet, his shield is similarly an oversized decorated parade item, and the gold and garnet decorated shoulder clasps probably fastened a leather tunic and imitate the epaulettes of Roman body armour. He also possessed a ring mail shirt, while a showy gold belt buckle and the garnet and gold fittings to his sword and sword belt help to complete the picture."[75]

Eighth and ninth centuries

Leggings were more elaborate from the seventh to the ninth centuries with Frankish dress fashion providing the inspiration. In wealthier graves of this time period, buckles could be found under the knees and ankles of skeletal remains. Lace remnants found near the legs of skeletons in Kent is another indication of Frankish influence in clothing.[51]

Art of this era was abundant in illustrations of English kings wearing long garments. The change from shorter tunics to long garments was likely influenced by European fashion. Gowns were often loose, with a variety of sleeve styles.[76]

Military dress

Historian Gale Owen-Crocker, in her book, Dress in Anglo-Saxon England writes, "Despite allusions to mailcoats in the heroic poetry of the Anglo-Saxon period, the general absence of archaeological evidence for them, even in graves equipped with fine weapons, suggests that, at least in the earlier centuries of the Anglo-Saxon era, they were a rare luxury, and it was not unusual to fight without protective clothing; on the Franks Casket some spear-carriers are not equipped with armour".[78]

Burial finds from the fourth or early fifth century in Oxfordshire (prior to the Anglo-Saxon migration) have found evidence that military leaders of that time period wore belts that were elaborate, wide, and fastened by "a narrow strap which was riveted to the broad belt and passed through a buckle which was much narrower than the belt itself" leaving the end of the belt to hang down; attached to the belt were pouches which allowed soldiers to carry their weapons.[79]

Archaeological excavations in the 1990s uncovered three 7th century male graves, each with tablet-woven bands. The clothing remnants appeared to be part of a jacket garment. The artefacts were analysed and later interpreted to be the front borders of a wrap-over fighting jacket, as seen on the Sutton Hoo helmet panels and other 7th century art.[80] Historians believe that Anglo-Saxon soldiers wore wrap-over, knee-length coats decorated like chain mail with sleeves that narrowed at the wrists. The jacket would be decorated with "patterned tablet woven bands stitched to the front opening and perhaps also to the hem and cuffs....Most of the comparative material suggests that the jacket was usually worn over trousers."[81] In the ninth and tenth centuries, military attire did not differ much from that of civil attire. The only changes were in the form of short linen tunics with metal collars and the addition of a sword, spear, shield, and helmet.[82] Weapons and clothes fittings worn on the battlefield were highly decorated with jewellery techniques, as seen in the discoveries at Sutton Hoo and in the Staffordshire Hoard; the concept of parade wear did not exist for the Anglo-Saxons.[78]

Dress and religion

19th century costume historian and writer, James Planché, believed that the clergy of the 9th and 10th centuries dressed similarly to the laity, except when saying mass. Beginning in the later 8th century, the clergy were forbidden to wear bright colours or expensive or valuable fabrics. He also asserted that the clergy wore linen stockings.[83]

The clergy of the 11th century had shaved heads and wore hats which, according to Planché, were "slightly sinking in the centre, with the pendent ornaments of the mitre attached to the side of it". Other garments included the chasuble, the outermost liturgical vestment, which retained its shape, and the dalmatics, a tunic like vestment with large, bell shaped sleeves, which tended to be arched on the sides. The pastoral staff was generally found to be plain in colour and ornamentation.[84]

Clothing construction

Raw materials

From the fifth to the eleventh centuries, the raw materials available to create textiles were wool from sheep, linen from flax, and imported silk. Wool was produced from a variety of sheep breeds, including primitive brown sheep (ancestors to the Soay sheep breed), white sheep brought by the Romans to Britain, and black-faced sheep that were introduced during the Viking invasions. Clothing made from the wool of sheep would be available in a selection of colour variations from white to brown and black. Silk was not cultivated in England but imported as finished garments, lengths of cloth, or sewing/embroidery threads.[85]

According to Owen-Crocker, "Linen production was a longer process, involved planting flax seed, weeding, harvesting, removal of seed pods, retting (rotting) the woody stems in water or a dewy field, drying, beating, and ‘scrutching’ the flax stems to break them and release the fibres inside, then repeated heckling or combing of those fibres to prepare them for spinning."[85]

Manufacturing

In the fifth and sixth centuries, women were the manufacturers of Anglo-Saxon clothing, weaving textiles on looms in their homes. About 70% of a woman's year was spent making textiles.[86] Between the seventh and ninth centuries, Anglo-Saxon communities changed slowly from small villages to larger villages and larger estates. Specialised workshops on the big estates would be responsible for the manufacture of textiles and clothing for the residents of the estate. In the tenth and eleventh centuries, the growth of urban centres around England changed the variety and quantity of materials, clothing, and accessories that people had access to and the way in which clothing and accessories were manufactured.[87][88]

Dye-testing of textile remnants from Anglo-Saxon graves has revealed that clothing was not dyed in the Anglo-Saxon era, except for tablet-woven-bands which edged women's garments. This could signify that artificial pigment was never present or that garment colour has been lost over time due to deterioration. It is probable that garments were not washed often. Washing would fade any artificial dyes that had been used, and laundering would diminish the natural weather-proof qualities of wool. Analysis of textile fragments from burial artefacts has indicated the absence of felting, which shows the lack of frequent washing.[7]

Anglo-Saxon jewellery

Men and women's garments were fastened by brooches, buckles, clasps and pins. Jewellery could be created from a variety of metals, including iron, copper alloy (bronze), silver or gold, or a combinations metals. The precious metals were obtained by melting down older metal objects, including Roman coins. Many brooches and buckles were decorated by techniques including casting, engraving and inlaying.[89]

Jewellery fashion

Fashion changes in women's jewellery occurred frequently in the Anglo-Saxon era. In sixth century Kent, for example, single jewelled disc brooches were in style until the end of the sixth century when more elaborate plate brooches with cloisonné garnet and glass settings were the fashion. This fashion trend was followed by opulent composite jewelled brooches that disappeared around the middle of the seventh century. Dress pins began to appear at the beginning of the seventh century. Pendants also became fashionable at this time. Necklets came into fashion, typically created with silver-wire rings and coloured glass beads.[90][91]

.jpg)

In male graves, belt sets with triangular plates inspired by Frankish fashion appear in the late sixth century and span the first half of the seventh century. Later in the seventh century, small buckles with rectangular plates become typical.[92]

Finger rings are worn in the early Anglo-Saxon era, but declined in popularity in the seventh and eighth centuries, and became fashionable again in the ninth century.[93] At the end of the seventh century, circular brooches increased in popularity over long brooches, and annular and disc brooches start appearing in grave-goods. Eighth century circular brooches are rarely found, but many examples have been found from the ninth to eleventh centuries. [94]

Brooches which resemble modern safety pins appear in the seventh century. Straight pins continue to be popular in the seventh century, and are sometimes made of gold and silver. Garlands of beads, which decorated women's garments in the fifth and sixth centuries, fade from view in the seventh century. The most noticeable jewellery fashion change in the seventh and eighth century was the use of necklace pendants. These style pendants were inspired by a combination of Frankish, Byzantine and Roman art. Straight pins continue to be popular in the tenth and eleventh centuries. They are considered functional items during this time period and are being mass-produced. Finger rings continue to be popular.[95]

.jpg)

Jewellery production

In the early Anglo-Saxon era, jewellery was created by itinerant craftsmen who would move from village to village. In the seventh thru the ninth centuries, the Anglo-Saxon communities changed slowly from small villages to increasingly larger villages and large estates. On larger estates, specialised workshops would be responsible for the manufacture of jewellery and metalwork for the residents of the estate. In the tenth and eleventh centuries, the growth of urban centers throughout England changed the variety and quantity of jewellery made available to Anglo-Saxons and the methods in which jewellery was produced.[96]

See also

References

Citations

- "History: the Anglo-Saxons". BBC. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, p. 6.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 10.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 97.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 100.

- "The Lexis of Cloth and Clothing project". The University of Manchester. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 95.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 101.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 98.

- Stoodley 1999, pp. 115–117.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, p. 242.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 38.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, pp. 178, 218.

- Welch 2011, p. 267.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 91–93.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, pp. 144.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 81.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, pp. 149.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, p. 109.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 182.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, p. 221.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 82.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 105.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 83.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 143–144.

- Welch 2011, p. 277.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 212.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 213, 220.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 213–215.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 217.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 82, 83.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 104–105.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, pp. 201, 203.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 105, 110.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, pp. 201–203.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 107, 181.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 112–114.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 115–118.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 118.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 82, 123.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 119, 126.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 126–127.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 166.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 111.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 171.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 173.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 178.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 178, 180.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 168.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 187.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 189.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 90.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 195, 199—200.

- Welch 2011, p. 278.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 199–200.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 192.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 233–234.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 234.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 234, 245.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 255–256.

- "The history of hand knitting". Virginia and Albert Museum. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 160.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 251.

- Owen-Crocker 2007, p. 128.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 102.

- Stoodley 1999, p. 108.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, pp. 217–218.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 266.

- Stoodley 1999, pp. 1991–1993.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, pp. 96, 111.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 228.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 199.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 181.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, pp. 111–112.

- Welch 2011, p. 269.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 240.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 244.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 193.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 120.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, pp. 210–211.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, pp. 213–214.

- Planché 1879, p. 41.

- Planché 1879, pp. 51–52.

- Planché 1879, p. 83.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 93.

- Walton-Rogers 2007, p. 9.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, pp. 94–95.

- Thomas 2011, pp. 408, 412—414.

- Owen-Crocker 2011, p. 96.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 141.

- Welch 2011, pp. 267, 277.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 143.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 146.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, p. 139.

- Owen-Crocker 2004, pp. 138–141.

- Thomas 2011, pp. 409, 412—414.

Bibliography

- Owen-Crocker, Gale R. (2004) [1986]. Dress in Anglo-Saxon England (rev. ed.). Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843830818.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Owen Crocker, Gale (2011). "Chapter 7: Dress and Identity". In Hamerow, Helena; Hinton, David A.; Crawford, Sally (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–116. ISBN 978-1-234-56789-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Planché, James Robinson (1879). A Cyclopaedia of Costume Or Dictionary of Dress, Including Notices of Contemporaneous Fashions on the Continent: A general chronological history of the costumes of the principal countries of Europe, from the commencement of the Christian era to the accession of George the Third. 2. London: Chatto and Windus. OCLC 760370.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stoodley, Nick (1999). The Spindle and the Spear: A Critical Enquiry into the Construction and Meaning of Gender in the Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Rite. British Archaeological Reports, British Series 288. ISBN 978-1841711171.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, Gabor (2011). "Chapter 22: Overview: Craft Production and Technology". In Hamerow, Helena; Hinton, David A.; Crawford, Sally (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology. Oxford University Press. pp. 266–287. ISBN 978-1-234-56789-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walton-Rogers, Penelope (2007). Cloth and Clothing in Early Anglo-saxon England AD 450-700. Council for British Archaeology. ISBN 978-1902771540.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Welch, Martin (2011). "Chapter 15: The Mid Saxon 'Final Phase'". In Hamerow, Helena; Hinton, David A.; Crawford, Sally (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology. Oxford University Press. pp. 266–287. ISBN 978-1-234-56789-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

Carver, Martin (1998). Sutton Hoo: Burial Ground of Kings?. Univ of Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0812234558.

Coatsworth, Elizabeth; Pinder, Michael (2012). The Art of the Anglo-Saxon Goldsmith: Fine Metalwork in Anglo-Saxon England: its Practice and Practitioners (Anglo-Saxon Studies). Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0851158839.

Dickinson, Tania M. (2005). "Symbols of Protection: The Significance of Animal-ornamented Shields in Early Anglo-Saxon England" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 49 (1): 109–163. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

Hamerow, Helena (2014). Rural Settlements and Society in Anglo-Saxon England (Medieval History and Archaeology). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198723127.

Hinton, David A. (1990). Archaeology, Economy and Society: England from the Fifth to the Fifteenth Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415188487.

Miller, Maureen C. (2014). Clothing the Clergy: Virtue and Power in Medieval Europe c. 800–1200. Cornell University. ISBN 978-0801479434.

Webster, Leslie (2016). Anglo Saxon Art: A New History. British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0714128092.