Heathenry (new religious movement)

Heathenry, also termed Heathenism, contemporary Germanic Paganism, or Germanic Neopaganism, is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religious studies classify it as a new religious movement. Developed in Europe during the early 20th century, its practitioners model it on the pre-Christian belief systems adhered to by the Germanic peoples of the Iron Age and Early Middle Ages. In an attempt to reconstruct these past belief systems, Heathenry uses surviving historical, archaeological, and folkloric evidence as a basis, although approaches to this material vary considerably.

_2010-07-10.jpg)

Heathenry does not have a unified theology but is typically polytheistic, centering on a pantheon of deities from pre-Christian Germanic Europe. It adopts cosmological views from these past societies, including an animistic view of the cosmos in which the natural world is imbued with spirits. The religion's deities and spirits are honored in sacrificial rites known as blóts in which food and libations are offered to them. These are often accompanied by symbel, the act of ceremonially toasting the gods with an alcoholic beverage. Some practitioners also engage in rituals designed to induce an altered state of consciousness and visions, most notably seiðr and galdr, with the intent of gaining wisdom and advice from the deities. Many solitary practitioners follow the religion by themselves. Other Heathens assemble in small groups, usually known as kindreds or hearths, to perform their rites outdoors or in specially constructed buildings. Heathen ethical systems emphasize honor, personal integrity, and loyalty, while beliefs about an afterlife vary and are rarely emphasized.

Heathenry's origins lie in the 19th- and early 20th-century Romanticism, which glorified the pre-Christian societies of Germanic Europe. Völkisch groups actively venerating the deities of these societies appeared in Germany and Austria during the 1900s and 1910s, although they largely dissolved following Nazi Germany's defeat in World War II. In the 1970s, new Heathen groups established in Europe and North America, developing into formalized organizations. A central division within the Heathen movement emerged surrounding the issue of race. Older groups adopted a racialist attitude—often termed "folkish" within the community—by viewing Heathenry as an ethnic or racial religion with inherent links to a Germanic race. They believe it should be reserved for white people, particularly of Northern European descent, and often combine the religion with white supremacist and far right-wing perspectives. A larger proportion of Heathens instead adopt a "universalist" perspective, holding that the religion is open to all, irrespective of origin.

While the term Heathenry is used widely to describe the religion as a whole, many groups prefer different designations, influenced by their regional focus and ideological preferences. Heathens focusing on Scandinavian sources sometimes use Ásatrú, Vanatrú, or Forn Sed; practitioners focusing on Anglo-Saxon traditions use Fyrnsidu or Theodism; those emphasising German traditions use Irminism; and those Heathens who espouse folkish and far-right perspectives tend to favor the terms Odinism, Wotanism, Wodenism, or Odalism. Scholarly estimates put the number of Heathens at no more than 20,000 worldwide, with communities of practitioners active in Europe, the Americas, and Australasia.

Definition

Scholars of religious studies classify Heathenry as a new religious movement,[1] and more specifically as a reconstructionist form of modern Paganism.[2] Heathenry has been defined as "a broad contemporary Pagan new religious movement (NRM) that is consciously inspired by the linguistically, culturally, and (in some definitions) ethnically 'Germanic' societies of Iron Age and early medieval Europe as they existed prior to Christianization",[3] and as a "movement to revive and/or reinterpret for the present day the practices and worldviews of the pre-Christian cultures of northern Europe (or, more particularly, the Germanic speaking cultures)".[4]

Practitioners seek to revive these past belief systems by using surviving historical source materials.[5] Among the historical sources used are Old Norse texts associated with Iceland such as the Prose Edda and Poetic Edda, Old English texts such as Beowulf, and Middle High German texts such as the Nibelungenlied. Some Heathens also adopt ideas from the archaeological evidence of pre-Christian Northern Europe and folklore from later periods in European history.[6] Among many Heathens, this material is referred to as the "Lore" and studying it is an important part of their religion.[7] Some textual sources nevertheless remain problematic as a means of "reconstructing" pre-Christian belief systems, because they were written by Christians and only discuss pre-Christian religion in a fragmentary and biased manner.[8] The anthropologist Jenny Blain characterises Heathenry as "a religion constructed from partial material",[9] while the religious studies scholar Michael Strmiska describes its beliefs as being "riddled with uncertainty and historical confusion", thereby characterising it as a postmodern movement.[10]

The ways in which Heathens use this historical and archaeological material differ; some seek to reconstruct past beliefs and practices as accurately as possible, while others openly experiment with this material and embrace new innovations.[11] Some, for instance, adapt their practices according to "unverified personal gnosis" (UPG) that they have gained through spiritual experiences.[12] Others adopt concepts from the world's surviving ethnic religions as well as modern polytheistic traditions such as Hinduism and Afro-American religions, believing that doing so helps to construct spiritual world-views akin to those that existed in Europe prior to Christianization.[13] Some practitioners who emphasize an approach that relies exclusively on historical and archaeological sources criticize such attitudes, denigrating those who practice them using the pejorative term "Neo-Heathen".[14]

Some Heathens seek out common elements found throughout Germanic Europe during the Iron Age and Early Middle Ages, using those as the basis for their contemporary beliefs and practices.[15] Conversely, others draw inspiration from the beliefs and practices of a specific geographical area and chronological period within Germanic Europe, such as Anglo-Saxon England or Viking Age Iceland.[15] Some adherents are deeply knowledgeable as to the specifics of Northern European society in the Iron Age and Early Medieval periods;[16] however for most practitioners their main source of information about the pre-Christian past is fictional literature and popular accounts of Norse mythology.[17] Many express a romanticized view of this past,[18] sometimes perpetuating misconceptions about it;[19] the sociologist of religion Jennifer Snook noting that many practitioners "hearken back to a more epic, anachronistic, and pure age of ancestors and heroes".[20]

The anthropologist Murphy Pizza suggests that Heathenry can be understood as an "invented tradition".[21] As the religious studies scholar Fredrik Gregorius states, despite the fact that "no real continuity" exists between Heathenry and the pre-Christian belief systems of Germanic Europe, Heathen practitioners often dislike being considered adherents of a "new religion" or "modern invention" and thus prefer to depict theirs as a "traditional faith".[22] Many practitioners avoid using the scholarly, etic term "reconstructionism" to describe their practices,[23] preferring to characterize it as an "indigenous religion" with parallels to the traditional belief systems of the world's indigenous peoples.[24] In claiming a sense of indigeneity, some Heathens—particularly in the United States—attempt to frame themselves as the victims of Medieval Christian colonialism and imperialism.[25] A 2015 survey of the Heathen community found equal numbers of practitioners (36%) regarding their religion as a reconstruction as those who regarded it as a direct continuation of ancient belief systems; only 22% acknowledged it to be modern but historically inspired, although this was the dominant interpretation among practitioners in Nordic countries.[26]

Terminology

No central religious authority exists to impose a particular terminological designation on all practitioners.[27] Hence, different Heathen groups have used different words to describe both their religion and themselves, with these terms often conveying meaning about their socio-political beliefs as well as the particular Germanic region of pre-Christian Europe from which they draw inspiration.[28]

Academics studying the religion have typically favoured the terms Heathenry and Heathenism to describe it,[29] for the reason that these words are inclusive of all varieties of the movement.[30] This term is the most commonly used option by practitioners in the United Kingdom,[31] with growing usage in North America and elsewhere.[32] These terms are based on the word heathen, attested as the Gothic haithn, which was adopted by Gothic Arian missionaries as the equivalent of both the Greek words Hellenis (Hellene, Greek) and ethnikós – "of a (foreign) people".[33] The word was used by Early Medieval Christian writers in Germanic Europe to describe non-Christians; by using it, practitioners seek to reappropriate it from the Christians as a form of self-designation.[34] Many practitioners favor the term Heathen over Pagan because the former term originated among Germanic languages, whereas Pagan has its origins in Latin.[35]

Further terms used in some academic contexts are contemporary Germanic Paganism[36] and Germanic Neopaganism,[37] although the latter is an "artificial term" developed by scholars with little use within the Heathen community.[38] Alternately, Blain suggested the use of North European Paganism as an overarching scholarly term for the movement;[39] Strmiska noted that this would also encompass those practitioners inspired by the belief systems of Northeastern Europe's linguistically Finnic and Slavic societies.[40] He favored Modern Nordic Paganism, but accepted that this term excluded those Heathens who are particularly inspired by the pre-Christian belief systems of non-Nordic Germanic societies, such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Goths.[40]

Another name for the religion is the Icelandic Ásatrú, which translates as "Æsir belief"—the Æsir being a sub-set of deities in Norse mythology. This is more commonly rendered as Asatru in North America, with practitioners being known as Asatruar.[41] This term is favored by practitioners who focus on the Nordic deities of Scandinavia,[42] however is problematic as many self-identified Asatruar worship entities other than the Æsir, such as the Vanir, valkyries, elves, and dwarfs.[43] Although initially a popular term of designation among practitioners and academics, usage of Ásatrú has declined as the religion has aged.[44]

Other practitioners term their religion Vanatrú, meaning "those who honor the Vanir", or Dísitrú, meaning "those who honor the goddesses", depending on their particular theological emphasis.[45] A small group of practitioners who venerate the Jötnar, refer to their tradition as Rokkatru.[46] Although restricted especially to Scandinavia, since the mid-2000s a term that has grown in popularity is Forn Siðr or Forn Sed ("the old way"); this is also a term reappropriated from Christian usage, having previously been used in a derogatory sense to describe pre-Christian religion in the Old Norse Heimskringla.[47] Other terms used within the community to describe their religion are the Northern Tradition, Norse Paganism, and Saxon Paganism,[48] while in the first third of the 20th century, commonly used terms were German, Nordic, or Germanic Faith.[49] Within the United States, groups emphasising a German-orientation have used Irminism, while those focusing on an Anglo-Saxon approach have used Fyrnsidu or Theodism.[50]

Many racialist-oriented Heathens prefer the terms Odinism or Wotanism to describe their religion.[51] The England-based racialist group Woden's Folk favored Wodenism and Woden Folk-Religion,[52] while another racialist group, the Heathen Front, favored the term Odalism, coined by Varg Vikernes, in reference to the odal rune.[53] There is thus a general view that all those who use Odinism adopt an explicitly political, right-wing and racialist interpretation of the religion, while Asatru is used by more moderate Heathen groups,[54] but no such clear division of these terms' usage exists in practice.[55] Gregorius noted that Odinism was "highly problematic" because it implies that the god Odin—who is adopted from Norse mythology—is central to these groups' theology, which is often not the case.[53] Moreover, the term is also used by at least one non-racialist group, the British Odinshof, who utilise it in reference to their particular dedication to Odin.[53]

Beliefs

Gods and spirits

The historian of religion Mattias Gardell noted that there is "no unanimously accepted theology" within the Heathen movement.[56] Several early Heathens like Guido von List found the polytheistic nature of pre-Christian religion embarrassing, and argued that in reality it had been monotheistic.[57] Since the 1970s, such negative attitudes towards polytheism have changed.[58] Today Heathenry is usually characterised as being polytheistic, exhibiting a theological structure which includes a pantheon of gods and goddesses, with adherents offering their allegiance and worship to some or all of them.[59] Most practitioners are polytheistic realists, referring to themselves as "hard" or "true polytheists" and believing in the literal existence of the deities as individual entities.[60] Others express a psychological interpretation of the divinities, viewing them for instance as symbols, Jungian archetypes or racial archetypes,[61] with some who adopt this position deeming themselves to be atheists.[62]

Heathenry's deities are adopted from the pre-Christian belief systems found in the various societies of Germanic Europe; they include divinities like Týr, Odin, Thor, Frigg and Freyja from Scandinavian sources, Wōden, Thunor and Ēostre from Anglo-Saxon sources, and figures such as Nehalennia from continental sources.[15] Some practitioners adopt the belief, taken from Norse mythology, that there are two sets of deities, the Æsir and the Vanir.[63] Certain practitioners blend the different regions and times together, for instance using a mix of Old English and Old Norse names for the deities, while others keep them separate and only venerate deities from a particular region.[64] Some groups focus their veneration on a particular deity; for instance, the Brotherhood of Wolves, a Czech Heathen group, center their worship on the deity Fenrir.[65] Similarly, many practitioners in the U.S. adopt a particular patron deity for themselves, taking an oath of dedication to them known as fulltruí, and describe themselves as that entity's devotee using terms such as Thorsman or Odinsman.[66]

Heathen deities are not seen as perfect, omnipotent, or omnipresent, and are instead viewed as having their own strengths and weaknesses.[67] Many practitioners believe that these deities will one day die, as did, for instance, the god Baldr in Norse mythology.[68] Heathens view their connection with their deities not as being that of a master and servant but rather as an interdependent relationship akin to that of a family.[69] For them, these deities serve as both examples and role models whose behavior is to be imitated.[70] Many practitioners believe that they can communicate with these deities,[71] as well as negotiate, bargain, and argue with them,[72] and hope that through venerating them, practitioners will gain wisdom, understanding, power, or visionary insights.[73] In Heathen ritual practices, the deities are typically represented as godpoles, wooden shafts with anthropomorphic faces carved into them, although in other instances resin statues of the divinities are sometimes used.[74]

Many practitioners combine their polytheistic world-view with a pantheistic conception of the natural world as being sacred and imbued with a divine energy force permeating all life.[75] Heathenry is animistic,[64] with practitioners believing in nonhuman spirit persons commonly known as "wights" (vættir) that inhabit the world,[76] each of whom is believed to have its own personality.[15] Some of these are known as "land spirits" (landvættir) and inhabit different aspects of the landscape, living alongside humans, whom they can both help and hinder.[77] Others are deemed to be household deities and live within the home, where they can be propitiated with offerings of food.[78] Some Heathens interact with these entities and provide offerings to them more often than they do with the gods and goddesses.[79] Wights are often identified with various creatures from Northwestern European folklore such as elves, dwarves, gnomes, and trolls.[80] Some of these entities—such as the Jötunn of Norse mythology—are deemed to be baleful spirits; within the community it is often deemed taboo to provide offerings to them, however some practitioners still do so.[81] Many Heathens also believe in and respect ancestral spirits, with ancestral veneration representing an important part of their religious practice.[82] For Heathens, relationships with the ancestors are seen as grounding their own sense of identity and giving them strength from the past.[83]

Cosmology and afterlife

Heathens commonly adopt a cosmology based on that found in Norse mythology—Norse cosmology. As part of this framework, humanity's world—known as Midgard—is regarded as just one of Nine Worlds, all of which are associated with a cosmological world tree called Yggdrasil. Different types of being are believed to inhabit these different realms; for instance, humans live on Midgard, while dwarfs live on another realm, elves on another, jötnar on another, and the divinities on two further realms.[84] Most practitioners believe that this is a poetic or symbolic description of the cosmos, with the different levels representing higher realms beyond the material plane of existence.[85] The world tree is also interpreted by some in the community as an icon for ecological and social engagement.[73] Some Heathens, such as the psychologist Brian Bates, have adopted an approach to this cosmology rooted in analytical psychology, thereby interpreting the nine worlds and their inhabitants as maps of the human mind.[73]

According to a common Heathen belief based on references in Old Norse sources, three female entities known as the Norns sit at the end of the world tree's root. These figures spin wyrd, which refers to the actions and interrelationships of all beings throughout the cosmos.[86] In the community, these three figures are sometimes termed "Past, Present and Future", "Being, Becoming, and Obligation" or "Initiation, Becoming, Unfolding".[87] It is believed that an individual can navigate through the wyrd, and thus, the Heathen worldview oscillates between concepts of free will and fatalism.[88] Heathens also believe in a personal form of wyrd known as örlög.[89] This is connected to an emphasis on luck, with Heathens in North America often believing that luck can be earned, passed down through the generations, or lost.[90]

Various Heathen groups adopt the Norse apocalyptic myth of Ragnarök; few view it as a literal prophecy of future events.[91] Instead, it is often treated as a symbolic warning of the danger that humanity faces if it acts unwisely in relation to both itself and the natural world.[91] The death of the gods at Ragnarök is often viewed as a reminder of the inevitability of death and the importance of living honorably and with integrity until one dies.[92] Alternately, ethno-nationalist Heathens have interpreted Ragnarök as a prophecy of a coming apocalypse in which the white race will overthrow who these Heathens perceive as their oppressors and establish a future society based on Heathen religion.[93] The political scientist Jeffrey Kaplan believed that it was the "strongly millenarian and chialistic overtones" of Ragnarök which helped convert white American racialists to the right wing of the Heathen movement.[94]

Some practitioners do not emphasize belief in an afterlife, instead stressing the importance of behaviour and reputation in this world.[95] In Icelandic Heathenry, there is no singular dogmatic belief about the afterlife.[96] A common Heathen belief is that a human being has multiple souls, which are separate yet linked together.[97] It is common to find a belief in four or five souls, two of which survive bodily death: one of these, the hugr, travels to the realm of the ancestors, while the other, the fetch, undergoes a process of reincarnation into a new body.[98] In Heathen belief, there are various realms that the hugr can enter, based in part on the worth of the individual's earthly life; these include the hall of Valhalla, ruled over by Odin, or Sessrúmnir, the hall of Freyja.[98] Beliefs regarding reincarnation vary widely among Heathens, although one common belief is that individuals are reborn within their family or clan.[99]

Morality and ethics

In Heathenry, moral and ethical views are based on the perceived ethics of Iron Age and Early Medieval Northwestern Europe,[100] in particular the actions of heroic figures who appear in Old Norse sagas.[101] Evoking a life-affirming ethos,[102] Heathen ethics focus on the ideals of honor, courage, integrity, hospitality, and hard work, and strongly emphasize loyalty to family.[103] It is common for practitioners to be expected to keep their word, particularly sworn oaths.[104] There is thus a strong individualist ethos focused around personal responsibility,[105] and a common motto within the Heathen community is that "We are our deeds".[106] Most Heathens reject the concept of sin and believe that guilt is a destructive rather than useful concept.[107]

Some Heathen communities have formalized such values into an ethical code, the Nine Noble Virtues (NNV), which is based largely on the Hávamál from the Poetic Edda.[108] This was first developed by the founders of the UK-based Odinic Rite in the 1970s,[109] although it has spread internationally, with 77% of respondents to a 2015 survey of Heathens reporting its use in some form.[110] There are different forms of the NNV, with the number nine having symbolic associations in Norse mythology.[111] Opinion is divided on the NNV; some practitioners deem them too dogmatic,[111] while others eschew them for not having authentic roots in historical Germanic culture,[112] negatively viewing them as an attempt to imitate the Judeo-Christian Ten Commandments.[113] Their use is particularly unpopular in Nordic countries,[114] and has been observed declining in the United States.[115]

Within the Heathen community of the United States, gender roles are based upon perceived ideals and norms found in Early Medieval Northwestern Europe, in particular as they are presented in Old Norse sources.[116] Among male American Heathens there is a trend toward hypermasculinized behaviour,[117] while a gendered division of labor—in which men are viewed as providers and women seen as being responsible for home and children—is also widespread among Heathens in the U.S.[118] Due to its focus on traditional attitudes to sex and gender—values perceived as socially conservative in Western nations—it has been argued that American Heathenry's ethical system is far closer to traditional Christian morals than the ethical systems espoused in many other Western Pagan religions such as Wicca.[119] A 2015 survey of the Heathen community nevertheless found that a greater percentage of Heathens were opposed to traditional gender rules than in favor of them, with this being particularly the case in Northern Europe.[120]

The sociologist Jennifer Snook noted that as with all religions, Heathenry is "intimately connected" to politics, with practitioners' political and religious beliefs influencing one another.[121] As a result of the religion's emphasis on honoring the land and its wights, many Heathens take an interest in ecological issues,[122] with many considering their faith to be a nature religion.[123] Heathen groups have participated in tree planting, raising money to purchase woodland, and campaigning against the construction of a railway between London and the Channel Tunnel in Southeastern England.[124] Many Germanic Neopagans are also concerned with the preservation of heritage sites,[125] and some practitioners have expressed concern regarding archaeological excavation of prehistoric and Early Medieval burials, believing that it is disrespectful to the individuals interred, whom Heathens widely see as their ancestors.[124]

Ethical debates within the community also arise when some practitioners believe that the religious practices of certain co-religionists conflict with the religion's "conservative ideas of proper decorum".[126] For instance, while many Heathens eschew worship of the Norse god Loki, deeming him a baleful wight, his gender-bending nature has made him attractive to many LGBT Heathens. Those who adopt the former perspective have thus criticized Lokeans as effeminate and sexually deviant.[127] Views on homosexuality and LGBT rights remain a source of tension within the community.[128] Some right-wing Heathen groups view homosexuality as being incompatible with a family-oriented ethos and thus censure same-sex sexual activity.[129] Other groups legitimize openness toward LGBT practitioners by reference to the gender-bending actions of Thor and Odin in Norse mythology.[130] There are, for instance, homosexual and transgender members of The Troth, a prominent U.S. Heathen organisation.[131] Many Scandinavian Heathen groups perform same-sex marriages,[132] and a group of self-described "Homo-Heathens" marched in the 2008 Stockholm Pride carrying a statue of the god Freyr.[133]

Rites and practices

In Anglophone countries, Heathen groups are typically called kindreds or hearths, or alternately sometimes as fellowships, tribes, or garths.[134] These are small groups, often family units,[135] and usually consist of between five and fifteen members.[104] They are often bound together by oaths of loyalty,[136] with strict screening procedures regulating the admittance of new members.[137] Prospective members may undergo a probationary period before they are fully accepted and welcomed into the group,[138] while other groups remain closed to all new members.[138] Heathen groups are largely independent and autonomous, although they typically network with other Heathen groups, particularly in their region.[139] There are other followers of the religion who are not affiliated with such groups, operating as solitary practitioners, with these individuals often remaining in contact with other practitioners through social media.[140] A 2015 survey found that the majority of Heathens identified as solitary practitioners, with Northern Europe constituting an exception to this; here, the majority of Heathens reported involvement in groups.[141]

Priests are often termed godhi, while priestesses are gydhja, adopting Old Norse terms meaning "god-man" and "god-woman" respectively, with the plural term being gothar.[142] These individuals are rarely seen as intermediaries between practitioners and deities, instead having the role of facilitating and leading group ceremonies and being learned in the lore and traditions of the religion.[143] Many kindreds believe that anyone can take on the position of priest, with members sharing organisational duties and taking turns in leading the rites.[104] In other groups, it is considered necessary for the individual to gain formal credentials from an accredited Heathen organisation in order to be recognised as a priest.[144] In a few groups—particularly those of the early 20th century which operated as secret societies—the priesthood is modelled on an initiatory system of ascending degrees akin to Freemasonry.[145]

Heathen rites often take place in non-public spaces, particularly in a practitioner's home.[146] In other cases, Heathen places of worship have been established on plots of land specifically purchased for the purpose; these can represent either a hörg, which is a sanctified place within nature like a grove of trees, or a hof, which is a wooden temple.[147] The Heathen community has made various attempts to construct hofs in different parts of the world.[148] In 2014 the Ásaheimur Temple was opened in Efri Ás, Skagafjörður, Iceland,[149] while in 2014 a British Heathen group called the Odinist Fellowship opened a temple in a converted 16th-century chapel in Newark, Nottinghamshire.[150] Heathens have also adopted archaeological sites as places of worship.[151] For instance, British practitioners have assembled for rituals at the Nine Ladies stone circle in Derbyshire,[152] the Rollright Stones in Warwickshire,[153] and the White Horse Stone in Kent.[154] Swedish Heathens have done the same at Gamla Uppsala, and Icelandic practitioners have met at Þingvellir.[151]

Heathen groups assemble for rituals in order to mark rites of passage, seasonal observances, oath takings, rites devoted to a specific deity, and for rites of need.[104] These rites also serve as identity practices which mark the adherents out as Heathens.[155] Strmiska noted that in Iceland, Heathen rituals had been deliberately constructed in an attempt to recreate or pay tribute to the ritual practices of pre-Christian Icelanders, although there was also space in which these rituals could reflect innovation, changing in order to suit the tastes and needs of contemporary practitioners.[156] In addition to meeting for ritual practices, many Heathen kindreds also organize study sessions to meet and discuss Medieval texts pertaining to pre-Christian religion;[157] among U.S. Heathens, it is common to refer to theirs as a "religion with homework".[7]

During religious ceremonies, many adherents choose to wear clothing that imitates the styles of dress worn in Iron Age and Early Medieval Northern Europe, sometimes termed "garb".[158] They also often wear symbols indicating their religious allegiance. The most commonly used sign among Heathens is Mjölnir, or Thor's hammer, which is worn as a pendant, featured in Heathen art, and used as a gesture in ritual. It is sometimes used to express a particular affinity with the god Thor, however is also often used as a symbol of Heathenism as a whole, in particular representing the resilience and vitality of the religion.[159] Another commonly used Heathen symbol is the valknut, used to represent the god Odin or Woden.[160] Practitioners also commonly decorate their material—and sometimes themselves, in the form of tattoos—with runes, the alphabet used by Early Medieval Germanic languages.[161]

Blót and sumbel

The most important religious rite for Heathens is called blót, which constitutes a ritual in which offerings are provided to the gods.[162] Blót typically takes place outdoors, and usually consists of an offering of mead, which is contained within a bowl. The gods are invoked and requests expressed for their aid, as the priest uses a sprig or branch of an evergreen tree to sprinkle mead onto both statues of the deities and the assembled participants. This procedure might be scripted or largely improvised. Finally, the bowl of mead is poured onto a fire, or onto the earth, as a final libation to the gods.[163] Sometimes, a communal meal is held afterward; in some groups this is incorporated as part of the ritual itself.[164] In other instances, the blót is simpler and less ritualized; in this case, it can involve a practitioner setting some food aside, sometimes without words, for either gods or wights.[165] Some Heathens perform such rituals on a daily basis, although for others it is a more occasional performance.[90] Aside from honoring deities, communal blóts also serve as a form of group bonding.[166]

In Iron Age and Early Medieval Northern Europe, the term blót was at times applied to a form of animal sacrifice performed to thank the deities and gain their favor.[167] Such sacrifices have generally proved impractical for most modern practitioners or altogether rejected, due in part to the fact that skills in animal slaughter are not widely taught, while the slaughter of animals is regulated by government in Western countries.[15] The Icelandic group Ásatrúarfélagið for instance explicitly rejects animal sacrifice.[168]

In 2007 Strmiska noted that a "small but growing" number of Heathen practitioners in the U.S. had begun performing animal sacrifice as a part of blót.[169] Such Heathens conceive of the slaughtered animal as a gift to the gods, and sometimes also as a "traveller" who is taking a message to the deities.[170] Groups who perform such sacrifices typically follow the procedure outlined in the Heimskringla: the throat of the sacrificial animal is slashed with a sharp knife, and the blood is collected in a bowl before being sprinkled onto both participants of the rite and statues of the gods.[171] Animals used for this purpose have included poultry as well as larger mammals like sheep and pigs, with the meat then being consumed by those attending the rite.[172] Some practitioners have made alterations to this procedure: Strmiska noted two American Heathens who decided to use a rifle shot to the head to kill the animal swiftly, a decision made after they witnessed a blót in which the animal's throat was cut incorrectly and it slowly died in agony; they felt that such practices would have displeased the gods and accordingly brought harm upon those carrying out the sacrifice.[173]

Another common ritual in Heathenry is sumbel, also spelled symbel, a ritual drinking ceremony in which the gods are toasted.[174] Sumbel often takes place following a blót.[175] In the U.S., the sumbel commonly involves a drinking horn being filled with mead and passed among the assembled participants, who either drink from it directly, or pour some into their own drinking vessels to consume. During this process, toasts are made, as are verbal tributes to gods, heroes, and ancestors. Then, oaths and boasts (promises of future actions) might be made, both of which are considered binding on the speakers due to the sacred context of the sumbel ceremony.[176] According to Snook, the sumbel has a strong social role, representing "a game of politicking, of socializing, cementing bonds of peace and friendship and forming new relationships" within the Heathen community.[177] During her ethnographic research, Pizza observed an example of a sumbel that took place in Minnesota in 2006 with the purpose of involving Heathen children; rather than mead, the drinking horn contained apple juice, and the toasting accompanied the children taping pictures of apples to a poster of a tree that symbolized the apple tree of Iðunn from Norse mythology.[178]

Seiðr and galdr

One religious practice sometimes found in Heathenry is seiðr, which has been described as "a particular shamanic trance ritual complex",[179] although the appropriateness of using "shamanism" to describe seiðr is debatable.[180] Contemporary seiðr developed during the 1990s out of the wider Neo-Shamanic movement,[181] with some practitioners studying the use of trance-states in other faiths, such as Umbanda, first.[182] A prominent form is high-seat or oracular seiðr, which is based on the account of Guðriðr in Eiríks saga. While such practices differ between groups, oracular seiðr typically involves a seiðr-worker sitting on a high seat while songs and chants are performed to invoke gods and wights. Drumming is then performed to induce an altered state of consciousness in the practitioner, who goes on a meditative journey in which they visualise travelling through the world tree to the realm of Hel. The assembled audience then provide questions for the seiðr-worker, with the latter offering replies based on information obtained in their trance-state.[183] Some seiðr-practitioners make use of entheogenic substances as part of this practice;[184] others explicitly oppose the use of any mind-altering drugs.[185]

Not all Heathens practice seiðr; given its associations with both the ambiguity of sexuality and gender and the gods Odin and Loki in their unreliable trickster forms, many on the Heathen movement's right wing disapprove of it.[186] While there are heterosexual male practitioners,[187] seiðr is largely associated with women and gay men,[188] and a 2015 survey of Heathens found that women were more likely to have engaged in it than men.[189] One member of the Troth, Edred Thorsson, developed forms of seiðr which involved sex magic utilizing sado-masochistic techniques, something which generated controversy in the community.[190] Part of the discomfort that some Heathens feel toward seiðr surrounds the lack of any criteria by which the community can determine whether the seiðr-worker has genuinely received divine communication, and the fear that it will be used by some practitioners merely to bolster their own prestige.[191]

Galdr is another Heathen practice involving chanting or singing.[192] As part of a galdr ceremony, runes or rune poems are also sometimes chanted, in order to create a communal mood and allow participants to enter into altered states of consciousness and request communication with deities.[193] Some contemporary galdr chants and songs are influenced by Anglo-Saxon folk magical charms, such as Æcerbot and the Nine Herbs Charm. These poems were originally written in a Christian context, although practitioners believe that they reflect themes present in pre-Christian, shamanistic religion, and thus re-appropriate and "Heathanise" them for contemporary usage.[194]

Some Heathens practice forms of divination using runes; as part of this, items with runic markings on them might be pulled out of a bag or bundle, and read accordingly.[195] In some cases, different runes are associated with different deities, one of the nine realms, or aspects of life.[196] It is common for Heathens to utilize the Common Germanic Futhark as a runic alphabet, although some practitioners instead adopt the Anglo-Saxon Futhorc or the Younger Futhark.[197] Some non-Heathens also use runes for divinatory purposes, with books on the subject being common in New Age bookstores.[198] Some Heathens practice magic, but this is not regarded as an intrinsic part of Heathenry because it was not a common feature of pre-Christian rituals in Iron Age and Early Medieval Germanic Europe.[199]

Festivals

Different Germanic Neopagan groups celebrate different festivals according to their cultural and religious focus.[104] The most widely observed Heathen festivals are Winter Nights, Yule, and Sigrblót, all of which were listed in his Heimskringla and are thus of ancient origin.[200] The first of these marks the start of winter in Northern Europe, while the second marks Midwinter, and the last marks the beginning of summer.[201] Additional festivals are also marked by Heathen practice throughout the year.[201] These often include days which commemorate individuals who fought against the Christianization of Northern Europe, or who led armies and settlers into new lands.[160] Some Heathen groups hold festivals dedicated to a specific deity.[160]

Some Heathens celebrate the eight festivals found in the Wheel of the Year, a tradition that they share with Wiccans and other contemporary Pagan groups.[202] Others celebrate only six of these festivals, as represented by a six-spoked Wheel of the Year.[203] The use of such festivals is criticized by other practitioners, who highlight that this system is of modern, mid-20th century origin and does not link with the original religious celebrations of the pre-Christian Germanic world.[201]

Heathen festivals can be held on the same day each year, however are often celebrated by Heathen communities on the nearest available weekend, so that those practitioners who work during the week can attend.[160] During these ceremonies, Heathens often recite poetry to honor the deities, which typically draw upon or imitate the Early Medieval poems written in Old Norse or Old English.[160] Mead or ale is also typically drunk, with offerings being given to deities,[160] while fires, torches, or candles are often lit.[160] There are also regional meetings of Heathens known as Things. At these, religious rites are performed, while workshops, stalls, feasts, and competitive games are also present.[204] In the U.S., there are two national gatherings, Althing and Trothmoot.[205]

Racial issues

— Religious studies scholar Mattias Gardell[206]

The question of race represents a major source of division among Heathens, particularly in the United States.[207] Within the Heathen community, one viewpoint holds that race is entirely a matter of biological heredity, while the opposing position is that race is a social construct rooted in cultural heritage. In U.S. Heathen discourse, these viewpoints are described as the folkish and the universalist positions, respectively.[208] These two factions—which Kaplan termed the "racialist" and "nonracialist" camps—often clash, with Kaplan claiming that a "virtual civil war" existed between them within the American Heathen community.[209] The universalist and folkish division has also spread to other countries;[210] in contrast to North America and much of Northern Europe, discussions of race rarely arise among the Icelandic Heathen community as a result of the nation-state's predominantly ethnically homogeneous composition.[211] A 2015 survey revealed a greater number of Heathens subscribed to universalist ideas than folkish ones.[212]

Contrasting with this binary division, Gardell divides Heathenry in the United States into three groups according to their stances on the issue of race: the "anti-racist" group which denounces any association between the religion and racial identity, the "radical racist" faction which sees it as the natural religion of the Aryan race that cannot rightly be followed by members of any other racial group, and the "ethnic" faction which seeks a middle-path by acknowledging the religion's roots in Northern Europe and its connection with those of Northern European heritage.[206] The religious studies scholar Egil Asprem deemed Gardell's threefold typology "indispensable in order to make sense of the diverging positions within the broader discourse" of Heathenry.[213] The religious studies scholar Stefanie von Schnurbein also adopted this tripartite division, although she referred to the groups as the "racial-religious", "a-racist", and "ethnicist" factions respectively.[214] The scholar of religion Ethan Doyle White instead returned to the dual division between the "universalist" and "folkish" groups, arguing that the latter could be subdivided among the "ethnicist" and "racial-religious" factions, both of whom "deem Heathenry to be a religion geared for a particular racial or ethno-cultural group (whether conceptualised as 'Nordic,' 'white,' or 'Aryan')".[215]

Exponents of the universalist, anti-racist approach believe that the deities of Northern Europe can call anyone to their worship, regardless of ethnic background.[216] This group rejects the folkish emphasis on race, believing that even if unintended, it can lead to the adoption of racist attitudes toward those of non-Northern European ancestry.[217] Universalist practitioners such as Stephan Grundy have emphasized the fact that ancient Northern Europeans were known to marry and have children with members of other ethnic groups, and that in Norse mythology the Æsir also did the same with Vanir, Jötun, and humans, thus using such points to critique the racialist view.[218] Universalists welcome practitioners of Heathenry who are not of Northern European ancestry; for instance, there are Jewish and African American members of the U.S.-based Troth, while many of its white members are married to spouses from different racial groups.[219] While sometimes retaining the idea of Heathenry as an indigenous religion, proponents of this view have sometimes argued that Heathenry is indigenous to the land of Northern Europe, rather than indigenous to any specific race.[220]

The folkish sector of the movement deems Heathenry to be the indigenous religion of a biologically distinct Nordic race.[124] Some practitioners explain this by asserting that the religion is intrinsically connected to the collective unconscious of this race,[221] with prominent American Heathen Stephen McNallen developing this into a concept which he termed "metagenetics".[222] McNallen and many others in the "ethnic" faction of Heathenry explicitly deny that they are racist, although Gardell noted that their views would be deemed racist under certain definitions of the word.[223] Gardell considered many "ethnic" Heathens to be ethnic nationalists,[224] and many folkish practitioners express disapproval of multiculturalism and the mixture of different races in modern Europe, advocating racial separatism.[124] This group's discourse contains much talk of "ancestors" and "homelands", concepts that may be very vaguely defined.[225] Those adopting the "ethnic" folkish position have been criticized by both universalist and ethno-centrist factions, the former deeming "ethnic" Heathenry a front for racism and the latter deeming its adherents race traitors for their failure to fully embrace white supremacism.[226]

Some folkish Heathens are white supremacists and explicit racists,[227] representing a "radical racist" faction that favours the terms Odinism, Wotanism, and Wodenism.[228] Kaplan stated that the "borderline separating racialist Odinism and National Socialism is exceedingly thin",[229] adding that this racialist wing inhabited "the most distant reaches" of the modern Pagan movement.[230] The historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke similarly stated that Odinism "represents the battlefront of racist paganism in support of a white Aryan revolutionary path".[231] Practitioners in this sector of the religion have paid tribute to Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany,[229] claimed that the white race is facing extinction at the hands of a Jewish world conspiracy,[232] and rejected Christianity as a creation of the Jews.[231] Several such groups, like the Asatru Folk Assembly (AFA) and the Wolves of Vinland, are designated as hate groups by the U.S. Southern Poverty Law Center.[233] Many in the inner circle of The Order, a white supremacist militant group active in the U.S. during the 1980s, described themselves as Odinists,[234] and various racist Heathens have espoused the Fourteen Words slogan developed by the Wotanist and Order member David Lane.[235] Some racist organisations, such as the Order of Nine Angles and the Black Order, combine elements of Heathenism with Satanism,[236] although other racist Heathens, such as Wotansvolk's Ron McVan, have denounced the integration of these differing religious traditions.[237]

Ethno-centrist Heathens are heavily critical of their universalist counterparts, often declaring that the latter have been misled by New Age literature and political correctness.[238] Snook stated that both mainstream media and early academic studies of American Heathenry had focused primarily on the racist elements within the movement, thus neglecting the religion's anti-racist wing.[239] Many anti-racist practitioners have expressed frustration that Heathenry is misrepresented by some journalists and academics as a racist movement,[240] using their online presence to stress their opposition to extreme-right politics.[241]

History

Romanticist and Völkisch predecessors

During the late 18th and 19th centuries, German Romanticism focused increasing attention on the pre-Christian belief systems of Germanic Europe, with various Romanticist intellectuals expressing the opinion that these ancient religions were "more natural, organic and positive" than Christianity.[242] Such an attitude was promoted by the scholarship of Romanticist intellectuals like Johann Gottfried Herder, Jacob Grimm, and Wilhelm Grimm.[243] This development went in tandem with a growth in nationalism and the idea of the volk, contributing to the establishment of the Völkisch movement in German-speaking Europe.[244] Criticising the Jewish roots of Christianity, in 1900 the Germanist Ernst Wachler published a pamphlet calling for the revival of a racialized ancient German religion.[245] Other writers such as Ludwig Fahrenkrog supported his claims, resulting in the formation of both the Bund fur Persönlichkeitskultur (League for the Culture of the Personality) and the Deutscher Orden in 1911 and then the Germanische-Deutsche Religionsgemeinschaft (Germanic-German Religious Community) in 1912.[246]

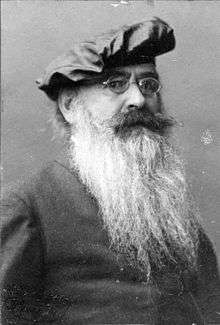

Another development of Heathenry emerged within the occult völkisch movement known as Ariosophy.[247] One of these völkisch Ariosophists was the Austrian occultist Guido von List, who established a religion that he termed "Wotanism", with an inner core that he referred to as "Armanism".[248] List's Wotanism was based heavily on the Eddas,[249] although over time it was increasingly influenced by the Theosophical Society's teachings.[250] List's ideas were transmitted in Germany by prominent right-wingers, and adherents to his ideas were among the founders of the Reichshammerbund in Leipzig in 1912, and they included individuals who held key positions in the Germanenorden.[251] The Thule Society founded by Rudolf von Sebottendorf developed from the Germanenorden, and it displayed a Theosophically-influenced interpretation of Norse mythology.[252]

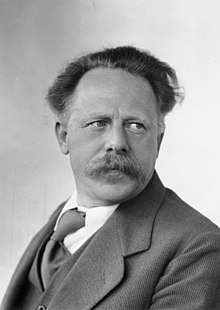

In 1933, the eclectic German Faith Movement (Deutsche Glaubensbewegung) was founded by the religious studies scholar Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, who wanted to unite these disparate Heathen groups. While active throughout the Nazi era, his hopes that his "German Faith" would be declared the official faith of Nazi Germany were thwarted.[253] The Heathen movement probably never had more than a few thousand followers during its 1920s heyday, however it held the allegiance of many middle-class intellectuals, including journalists, artists, illustrators, scholars, and teachers, and thus exerted a wider influence on German society.[254]

The völkisch occultists—among them Pagans like List and Christians like Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels—"contributed importantly to the mood of the Nazi era".[255] Few had a direct influence on the Nazi Party leadership, with one prominent exception: Karl Maria Wiligut was both a friend and a key influence on the Schutzstaffel (SS) leader Heinrich Himmler.[255] Wiligut professed ancestral-clairvoyant memories of ancient German society, proclaiming that "Wotanism" was in conflict with another ancient religion, "Irminenschaft", which was devoted to a messianic Germanic figure known as Krist, who was later wrongly transformed into the figure of Jesus.[256] Many Heathen groups disbanded during the Nazi period,[257] and they were only able to re-establish themselves after World War II, in West Germany, where freedom of religion had been re-established.[258] After the defeat of Nazi Germany, there was a social stigma surrounding völkisch ideas and groups,[259] along with a common perception that the mythologies of the pre-Christian Germanic societies had been tainted through their usage by the Nazi administration, an attitude that to some extent persisted into the 21st century.[260]

The völkisch movement also manifested itself in 1930s Norway within the milieu surrounding such groups as the Ragnarok Circle and Hans S. Jacobsen's Tidsskriftet Ragnarok journal. Prominent figures involved in this milieu were the writer Per Imerslund and the composer Geirr Tveitt, although it left no successors in post-war Norway.[261] A variant of "Odinism" was developed by the Australian Alexander Rud Mills, who published The Odinist Religion (1930) and established the Anglecyn Church of Odin. Politically racialist, Mills viewed Odinism as a religion for what he considered to be the "British race", and he deemed it to be in a cosmic battle with the Judeo-Christian religion.[262] Having formulated "his own unique blend" of Ariosophy,[263] Mills was heavily influenced by von List's writings.[264] Some of Heathenry's roots have also been traced back to the "back to nature" movement of the early 20th century, among them the Kibbo Kift and the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry.[265]

Modern development

In the early 1970s, Heathen organisations emerged in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and Iceland, largely independently from each other.[266] This has been partly attributed to the wider growth of the modern Pagan movement during the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the development of the New Age milieu, both of which encouraged the establishment of new religious movements intent on reviving pre-Christian belief systems.[267] Further Heathen groups then emerged in the 1990s and 2000s, many of which distanced themselves from overtly political agendas and placed a stronger emphasis on historical authenticity than their 1960s and 1970s forebears.[268]

Heathenry emerged in the United States during the 1960s.[269] In 1969 the Danish Heathen Else Christensen established the Odinist Fellowship at her home in the U.S. state of Florida.[270] Heavily influenced by Mills' writings,[271] she began publishing a magazine, The Odinist,[272] which placed greater emphasis on right-wing and racialist ideas than theological ones.[273] Stephen McNallen first founded the Viking Brotherhood in the early 1970s, before creating the Asatru Free Assembly in 1976, which broke up in 1986 amid widespread political disagreements after McNallen's repudiation of neo-Nazis within the group. In the 1990s, McNallen founded the Asatru Folk Assembly (AFA), an ethnically-oriented Heathen group headquartered in California.[274] Meanwhile, Valgard Murray and his kindred in Arizona founded the Ásatrú Alliance (AA) in the late 1980s, which shared the AFA's perspectives on race and which published the Vor Tru newsletter.[275] In 1987, Stephen Flowers and James Chisholm founded The Troth, which was incorporated in Texas. Taking an inclusive, non-racialist view, it soon grew into an international organisation.[276]

In Iceland, the influence of pre-Christian belief systems still pervaded the country's cultural heritage into the 20th century.[277] There, farmer Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson founded the Heathen group Ásatrúarfélagið in 1972, which initially had 12 members.[278] Beinteinsson served as Allsherjargodi (chief priest) until his death in 1993, when he was succeeded by Jormundur Ingi Hansen.[279] As the group expanded in size, Hansen's leadership caused schisms, and to retain the unity of the movement, he stepped down and was replaced by Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson in 2003, by which time Ásatrúarfélagið had accumulated 777 members and played a visible role in Icelandic society.[280] In England, the British Committee for the Restoration of the Odinic Rite was established by John Yeowell in 1972.[281] In 1992, Mark Mirabello published Odin Brotherhood, which claimed the existence of a secret society of Odinists; most British Heathens doubt its existence.[282]

In Sweden, the first Heathen groups developed in the 1970s; early examples included the Breidablikk-Gildet (Guild of Breidablikk) founded in 1975 and the Telge Fylking founded in 1987, the latter of which diverged from the former by emphasising a non-racialist interpretation of the religion.[283] In 1994, the Sveriges Asatrosamfund (Swedish Asatru Assembly) was founded, growing to become the largest Heathen organisation in the country.[284] The first Norwegian Heathen group, Blindern Åsatrulag, was established as a student group at the University of Oslo in the mid-1980s,[285] while the larger Åsatrufellesskapet Bifrost was established in 1996; after a schism in that group, the Foreningen Forn Sed was formed in 1999.[286] In Denmark, a small group was founded near to Copenhagen in 1986, however a wider Heathen movement would not appear until the 1990s, when a group calling itself Forn Siðr developed.[287]

In Germany, various groups were established that explicitly rejected their religion's völkisch and right-wing past, most notably Rabenclan (Raven's Clan) in 1994 and Nornirs Ætt (Kin of the Norns) in 2005.[288] Several foreign Heathen organisations also established a presence in the German Heathen scene; in 1994 the Odinic Rite Deutschland (Odinic Rite Germany) was founded, although it later declared its independence and became the Verein für germanisches Heidentum VfgH (Society for Germanic Paganism), while the Troth also created a German group, Eldaring, which declared its independence in 2000.[289] The first organised Heathen groups in the Czech Republic emerged in the late 1990s.[290] From 2000 to 2008, a Czech Heathen group that adopted a Pan-Germanic approach to the religion was active under the name of Heathen Hearts from Biohaemum.[291]

Heathen influences were apparent in forms of black metal from the 1990s, where lyrics and themes often expressed a longing for a pre-Christian Northern past; the mass media typically associated this music genre with Satanism.[292] The Pagan metal genre—which emerged from the fragmentation of the extreme metal scene in Northern Europe during the early 1990s[293]—came to play an important role in the North European Pagan scene.[294] Many musicians involved in Viking metal were also practicing Heathens,[295] with many metal bands embracing the heroic masculinity embodied in Norse mythological figures like Odin and Thor.[296] Heathen themes also appeared in the neofolk genre.[297] From the mid-1990s, the Internet greatly aided the propagation of Heathenry in various parts of the world.[298] That decade also saw the strong growth of racist Heathenry among those incarcerated within the U.S. prison system as a result of outreach programs established by various Heathen groups,[299] a project begun in the 1980s.[300] During this period, many Heathen groups also began to interact increasingly with other ethnic-oriented Pagan groups in Eastern Europe, such as Lithuanian Romuva, and many joined the World Congress of Ethnic Religions upon its formation in 1998.[301]

Demographics

Adherents of Heathenry can be found in Europe, North America, and Australasia,[302] with more recent communities also establishing in Latin America.[303] They are mostly found in those areas with a Germanic cultural inheritance, although they are present in several other regions.[304] In 2007, the religious studies scholar Graham Harvey stated that it was impossible to develop a precise figure for the number of Heathens across the world.[305] A self-selected census in 2013 found 16,700 members in 98 countries, the bulk of whom lived in the United States.[306][307] In 2016, Schnurbein stated that there were probably no more than 20,000 Heathens globally.[308]

Schnurbein noted that, while there were some exceptions, most Heathen groups were 60–70% male in their composition.[309] On the basis of his sociological research, Joshua Marcus Cragle agreed that the religion contained a greater proportion of men than women, but observed that there was a more even balance between the two in Northern and Western Europe than in other regions.[310] He also found that the Heathen community contained a greater percentage of transgender individuals, at 2%, than is estimated to be present in the wider population.[310] Similarly, Cragle's research found a greater proportion of LGBT practitioners within Heathenry (21%) than wider society, although noted that the percentage was lower than in other forms of modern Paganism.[36] Cragle also found that in every region except Latin America, the majority of Heathens were middle-aged,[310] and that most were of European descent.[311]

Many Heathens cite a childhood interest in German folk tales or Norse myths as having led them to take an interest in Heathenry; others have instead attributed their introduction to depictions of Norse religion in popular culture.[312] Some others claim to have involved themselves in the religion after experiencing direct revelation through dreams, which they interpret as having been provided by the gods.[313] As with other religions, a sensation of "coming home" has also been reported by many Heathens who have converted to the movement,[314] however Calico thought such a narrative was "not characteristic" of most U.S. Heathens.[315] Pizza suggested that, on the basis of her research among the Heathen community in the American Midwest, that many Euro-American practitioners were motivated to join the movement both out of a desire to "find roots" within historical European cultures and to meet "a genuine need for spiritual connections and community".[316]

Cragle's 2015 survey indicated that 45% of Heathens had been raised as Christians, although 21% had previously had no religious affiliation or been atheists or agnostics.[317] Practitioners typically live within Christian majority societies, however often state that Christianity has little to offer them.[318] In referring to Heathens in the U.S., Snook, Thad Horrell, and Kristen Horton noted that practitioners "almost always formulate oppositional identities" to Christianity.[319] Through her research, Schnurbein found that during the 1980s many Heathens in Europe had been motivated to join the religion in part by their own anti-Christian ethos, but that this attitude had become less prominent among the Heathen community as the significance of the Christian churches had declined in Western nations after that point.[320] Conversely, in 2018 Calico noted that a "deep antipathy" to Christianity was still "quite close to the surface for many American Heathens",[321] with anti-Christian sentiment often being expressed through humor in that community.[322] Many Heathens are also involved in historical reenactment, focusing on the early medieval societies of Germanic Europe; others are critical of this practice, believing that it blurs the boundary between real life and fantasy.[323] Some adherents also practice Heathenry in tandem with other Pagan religions, such as Wicca or Druidry,[324] however many others look unfavorably on such religions for being too syncretic.[325]

North America

The United States likely contains the largest Heathen community in the world.[326] While deeming it impossible to calculate the exact size of the Heathen community in the U.S., in the mid-1990s the sociologist Jeffrey Kaplan estimated that there were around 500 active practitioners in the country, with a further thousand individuals on the periphery of the movement.[327] He noted that the overwhelming majority of individuals in the American Heathen community were white, male, and young. Most had at least an undergraduate degree, and worked in a mix of white collar and blue collar jobs.[328]

The Pagan Census project led by Helen A. Berger, Evan A. Leach, and Leigh S. Shaffer gained 60 responses from Heathens in the U.S. Of these respondents, 65% were male and 35% female, which Berger, Leach, and Shaffer noted was the "opposite" of the female majority trend within the rest of the country's Pagan community.[329] The majority had a college education, but were generally less well educated than the wider Pagan community, and also had a lower median income.[329] From her experience within the community, Snook concurred that the majority of American Heathens were male, adding that most were white and middle-aged,[330] but believed that there had been a growth in the proportion of female Heathens in the U.S. since the mid-1990s.[331] Subsequent assessments have suggested a larger support base; 10,000 to 20,000 according to McNallen in 2006,[332] and 7,878 according to the 2014 census.[307][333] In 2018, the scholar of religion Jefferson F. Calico suggested that it was likely there were between 8000 and 20,000 Heathens in the U.S.[334]

Europe

In the United Kingdom Census 2001, 300 people registered as Heathen in England and Wales.[135] Many Heathens followed the advice of the Pagan Federation (PF) and simply described themselves as "Pagan", while other Heathens did not specify their religious beliefs.[135] In the 2011 census, 1,958 people self-identified as Heathen in England and Wales.[335]

By 2003, the Icelandic Heathen organisation Ásatrúarfélagið had 777 members,[336] by 2015, it reported 2,400 members,[337] and by January 2017 it claimed 3,583 members, constituting just over 1% of the Icelandic population.[338] In Iceland, Heathenry has an impact larger than the number of its adherents.[339] Based on his experience researching Danish Heathens, Amster stated that while it was possible to obtain membership figures of Heathen organisations, it was "impossible to estimate" the number of unaffiliated solo practitioners.[340] Conversely, in 2015, Gregorius estimated that there were at most a thousand Heathens in Sweden—both affiliated and unaffiliated—however observed that practitioners often perceived their numbers as being several times higher than this.[341] Although noting that there were no clear figures available for the gender balance within the community, he cited practitioners who claim that there are more men active within Swedish Heathen organisations.[342] Schnurbein observed that most Heathens in Scandinavia were middle-class professionals aged between thirty and sixty.[320]

There are a small number of Heathens in Poland, where they have established a presence on social media.[343] The majority of these Polish Heathens belong to the non-racist wing of the movement.[344] There are also a few Heathens in the Slovenian Pagan scene, where they are outnumbered by practitioners of Slavic Native Faith.[345] Exponents of Heathenry are also found on websites in Serbia.[346] In Russia, several far-right groups merge elements from Heathenry with aspects adopted from Slavic Native Faith and Russian Orthodox Christianity.[347] There are also several Heathens in the Israeli Pagan scene.[348]

See also

References

Footnotes

- Kaplan 1997, p. 70; Gardell 2003, p. 2; Gregorius 2015, p. 64; Velkoborská 2015, p. 89; Doyle White 2017, p. 242.

- Blain 2005, pp. 183–184; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 138; Horrell 2012, p. 1; Pizza 2014, p. 48; Snook 2015, p. 9.

- Doyle White 2017, p. 242.

- Horrell 2012, p. 1.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 138.

- Blain 2005, pp. 182, 185–186; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 138–141; Snook 2015, p. 12; Schnurbein 2016, p. 252; Calico 2018, p. 39.

- Calico 2018, p. 66.

- Snook 2015, p. 53.

- Blain 2005, p. 182.

- Strmiska 2000, p. 106.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 159.

- Blain & Wallis 2009, p. 414; Snook 2015, p. 50; Calico 2018, p. 40.

- Blain 2005, p. 185; Gregorius 2015, pp. 74, 75.

- Snook 2015, p. 49.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 126.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 137; Schnurbein 2016, p. 251.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 251.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 141.

- Doyle White 2014, p. 303.

- Snook 2015, p. 60.

- Pizza 2015, p. 497.

- Gregorius 2015, p. 64.

- Blain 2005, p. 184.

- Horrell 2012, p. 5; Snook 2015, p. 145; Gregorius 2015, p. 74.

- Snook, Horrell & Horton 2017, p. 58.

- Cragle 2017, pp. 101–103.

- Harvey 1995, p. 52.

- Snook 2015, pp. 8–9; Doyle White 2017, p. 242.

- Gregorius 2015, pp. 65–66; Doyle White 2017, p. 242.

- Snook 2015, p. 9; Cragle 2017, p. 79.

- Harvey 1995, p. 52; Blain 2002, p. 6; Blain 2005, p. 181; Blain & Wallis 2009, p. 415.

- Blain 2002, p. 6; Gardell 2003, p. 31; Davy 2007, p. 158; Snook 2013, p. 52.

- Gründer 2008, p. 16.

- Gardell 2003, p. 31; Blain 2005, p. 181; Schnurbein 2016, p. 10.

- Harvey 1995, p. 49; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 128; Harvey 2007, p. 53.

- Cragle 2017, p. 85.

- Granholm 2011, p. 519; Schnurbein 2016, p. 9.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 11.

- Blain 2002, p. 5.

- Strmiska 2007, p. 155.

- Blain 2002, p. 5; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 128; Adler 2006, p. 286; Harvey 2007, p. 53; Snook 2015, p. 9.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 128.

- Strmiska 2000, p. 113; Amster 2015, pp. 44–45.

- Gregorius 2015, p. 65.

- Harvey 1995, p. 53; Harvey 2007, p. 53.

- Calico 2018, p. 295.

- Blain 2002, p. 5; Gregorius 2015, pp. 65, 75; Schnurbein 2016, p. 10.

- Blain 2005, p. 182; Davy 2007, p. 158.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 9.

- Strmiska 2007, p. 167; Snook 2013, p. 53.

- Gardell 2003, p. 165; Harvey 2007, p. 53.

- Doyle White 2017, p. 254.

- Gregorius 2006, p. 390.

- Gardell 2003, p. 152; Asprem 2008, p. 45.

- Gardell 2003, p. 152; Doyle White 2017, p. 242.

- Gardell 2003, p. 156.

- Schnurbein 2016, pp. 93–94.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 94.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 126; Gardell 2003, p. 154; Blain 2005, p. 186; Harvey 2007, p. 55; Davy 2007, p. 159.

- Gardell 2003, pp. 156, 267; Blain 2005, p. 186; Harvey 2007, p. 57; Davy 2007, p. 159; Schnurbein 2016, pp. 94–95; Calico 2018, p. 287.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 71; Gardell 2003, pp. 156, 267; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 143; Schnurbein 2016, p. 94.

- Amster 2015, p. 48.

- Gardell 2003, p. 155; Blain 2005, p. 187; Harvey 2007, p. 55.

- Blain 2005, p. 188.

- Velkoborská 2015, p. 103.

- Snook 2015, p. 76; Schnurbein 2016, pp. 95–96; Calico 2018, p. 271.

- Gardell 2003, p. 268; Snook 2015, p. 57; Schnurbein 2016, p. 95.

- Harvey 1995, p. 51; Gardell 2003, p. 268; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 142; Harvey 2007, p. 55.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 72; Gardell 2003, p. 268.

- York 1995, p. 125.

- Blain 2005, p. 186.

- Blain 2005, p. 189.

- Harvey 2007, p. 57.

- Calico 2018, pp. 288–289.

- Gardell 2003, p. 268.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 126; Blain 2005, p. 187; Harvey 2007, p. 56; Davy 2007, p. 159.

- Harvey 2007, p. 56; Snook 2015, p. 13.

- Blain 2005, pp. 187–188.

- Snook 2015, p. 13.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 126; Snook 2015, p. 64.

- Strmiska 2007, pp. 174–175; Blain 2005, p. 187.

- Blain 2005, p. 187; Calico 2018, p. 254.

- Calico 2018, p. 262.

- Gardell 2003, p. 154; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 142; Blain 2005, p. 190; Harvey 2007, p. 54; Davy 2007, p. 159; Schnurbein 2016, p. 98.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 143; Harvey 2007, p. 57.

- Blain 2005, p. 190; Harvey 2007, pp. 55–56; Schnurbein 2016, p. 100.

- Harvey 2007, p. 55.

- Harvey 2007, p. 56; Schnurbein 2016, p. 99.

- Blain 2002, p. 15; Calico 2018, p. 231.

- Snook 2015, p. 64.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 142.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 142–143.

- Gardell 2003, pp. 279–280.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 69.

- Snook 2015, p. 57.

- Strmiska 2000, p. 121.

- Gardell 2003, p. 161; Snook 2015, pp. 58–59.

- Gardell 2003, p. 161.

- Gardell 2003, p. 161; Schnurbein 2016, p. 99.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 146.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 139.

- Gardell 2003, p. 157.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 139.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Schnurbein 2016, p. 104.

- Snook 2015, p. 70.

- Adler 2006, p. 291.

- Gardell 2003, p. 157; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 143, 145; Blain & Wallis 2009, p. 424; Snook 2015, pp. 70–71; Cragle 2017, p. 98.

- Doyle White 2017, p. 252.

- Cragle 2017, pp. 98–99.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 145.

- Snook 2015, p. 72.

- Snook 2015, p. 72; Cragle 2017, p. 100.

- Gregorius 2015, p. 78; Cragle 2017, p. 100.

- Calico 2018, p. 90.

- Snook 2015, p. 110.

- Snook 2015, pp. 116–117.

- Snook 2015, p. 113.

- Snook 2015, p. 45.

- Cragle 2017, pp. 83–84.

- Snook 2015, pp. 18–19.

- Blain 2005, p. 205; Harvey 2007, p. 65; Schnurbein 2016, p. 184.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 183.

- Harvey 2007, p. 66.

- Blain 2005, p. 205; Schnurbein 2016, p. 184.

- Snook 2015, p. 74.

- Snook 2015, pp. 73–74; Schnurbein 2016, p. 97.

- Blain 2005, p. 204.

- Blain 2005, p. 204; Schnurbein 2016, p. 244.

- Gregorius 2015, p. 79.

- Kaplan 1996, p. 224; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 128.

- Schnurbein 2016, pp. 246–247.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 247.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Gardell 2003, p. 157; Blain 2005, p. 191; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 131; Davy 2007, p. 159; Snook 2015, pp. 22, 85.

- Blain 2005, p. 191.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 131; Snook 2015, p. 92.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 133.

- Snook 2015, p. 92.

- Blain 2005, p. 193; Snook 2015, p. 93.

- Gardell 2003, p. 157; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 131; Snook 2015, p. 85.

- Cragle 2017, pp. 96–97.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Gardell 2003, p. 158; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 132; Snook 2015, p. 90; Schnurbein 2016, p. 113.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 132; Harvey 2007, p. 61.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Snook 2015, p. 91; Schnurbein 2016, p. 113.

- Schnurbein 2016, pp. 112–113.

- Snook 2015, p. 22.

- Gardell 2003, p. 159.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 109.

- Helgason, Magnús Sveinn (7 August 2015). "Visit the only heathen temple in Iceland in Skagafjörður fjord for a pagan grill party this Saturday". Iceland Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 October 2015.

- Millard, Lucy (18 June 2015). "World's first modern-day pagan temple is in Newark". Newark Advertiser. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 108.

- Blain & Wallis 2007, p. 140.

- Blain & Wallis 2007, p. 178.

- Doyle White 2016, p. 352; Doyle White 2017, p. 253.

- Blain 2005, p. 195.

- Strmiska 2000, p. 118.

- Calico 2018, p. 69.

- Harvey 2007, p. 59; Calico 2018, pp. 22–23.

- Gardell 2003, p. 55; Harvey 2007, p. 59; Davy 2007, p. 159; Snook 2015, pp. 9–10.

- Harvey 2007, p. 59.

- Calico 2018, pp. 391–392.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 126; Blain 2005, p. 194; Adler 2006, p. 294; Schnurbein 2016, p. 106.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, pp. 126–127; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 130; Blain 2005, p. 195.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 126; Schnurbein 2016, p. 107.

- Blain 2005, p. 194.

- Blain 2005, pp. 194–195; Schnurbein 2016, p. 107.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 126; Strmiska 2007, p. 165.

- For example, the Ásatrúarfélagið's website state that "We particularly reject the use of Ásatrú as a justification for supremacy ideology, militarism and animal sacrifice." Ásatrúarfélagið. Online.

- Strmiska 2007, p. 156.

- Calico 2018, pp. 316–317.

- Strmiska 2007, p. 166.

- Strmiska 2007, p. 168.

- Strmiska 2007, pp. 169–170, 183.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Gardell 2003, pp. 159–160; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 129–130; Blain 2005, p. 194.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Blain 2005, p. 195.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 129; Adler 2006, p. 291; Calico 2018, p. 347.

- Snook 2015, p. 11.

- Pizza 2014, p. 47; Pizza 2015, p. 495.

- Harvey 2007, p. 62.

- Blain 2002, pp. 47–50.

- Adler 2006, p. 396.

- Magliocco 2004, pp. 226–227.

- Blain 2002, pp. 32–33; Adler 2006, p. 296.

- Blain 2002, p. 57; Velkoborská 2015, p. 93.

- Blain 2002, p. 57.

- Blain 2002, p. 15; Blain 2005, p. 206; Harvey 2007, p. 62; Schnurbein 2016, pp. 113, 121.

- Snook 2015, p. 137.

- Blain 2002, p. 18; Snook 2015, p. 137; Schnurbein 2016, p. 243.

- Cragle 2017, p. 104.

- Kaplan 1996, pp. 221–222; Schnurbein 2016, p. 246.

- Strmiska 2007, p. 171.

- Blain 2005, p. 196.

- Harvey 2007, pp. 61–62.

- Blain 2005, p. 196; Blain & Wallis 2009, pp. 426–427.

- Blain 2005, p. 196; Harvey 2007, p. 61; Calico 2018, p. 118.

- Harvey 2007, p. 61.

- Blain 2005, p. 196; Blain & Wallis 2009, p. 425.

- Harvey 1995, p. 49.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Blain & Wallis 2009, p. 425.

- Hunt-Anschutz 2002, p. 127; Harvey 2007, p. 58; Davy 2007, p. 159; Blain & Wallis 2009, p. 420.

- Harvey 2007, p. 58.

- Harvey 2007, p. 58; Blain & Wallis 2009, p. 420.

- Adler 2006, p. 287.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 131–132.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 132.

- Gardell 2003, p. 153.

- Kaplan 1996, p. 202; Gardell 2003, p. 153; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 134; Blain 2005, p. 193.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 134–135; Adler 2006, pp. 29–294; Blain & Wallis 2009, p. 422; Schnurbein 2016, p. 128; Snook, Horrell & Horton 2017, p. 52.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 78.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 128.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 165.

- Cragle 2017, p. 90.

- Asprem 2008, p. 48.

- Schnurbein 2016, pp. 6–7.

- Doyle White 2017, pp. 242–243.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, pp. 134–135.

- Harvey 2007, p. 67.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 77; Gardell 2003, p. 163.

- Kaplan 1996, p. 224; Gardell 2003, p. 164; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 128.

- Blain 2005, p. 193.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 81; Harvey 2007, pp. 66–67.

- Kaplan 1997, pp. 80–82; Gardell 2003, pp. 269–273; Schnurbein 2016, p. 130.

- Gardell 2003, p. 271.

- Gardell 2003, p. 278.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 137.

- Gardell 2003, pp. 273–274.

- Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 136; Schnurbein 2016, p. 129.

- Gardell 2003, p. 165; Doyle White 2017, p. 254.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 85.

- Kaplan 1997, pp. 69–70.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2003, p. 257.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 86.

- "Neo-Volkisch". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Gardell 2003, pp. 196–197.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 94.

- Gardell 2003, pp. 292–293.

- Gardell 2003, pp. 320–321.

- Gardell 2003, p. 165.

- Snook 2015, pp. 13–14.

- Cragle 2017, p. 89.

- Doyle White 2017, p. 257.

- Granholm 2011, pp. 520–521.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 17.

- Granholm 2011, p. 521; Schnurbein 2016, p. 17.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 38.

- Schnurbein 2016, pp. 38–40.

- Schnurbein 2016, p. 40.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 52; Gregorius 2006, p. 390; Granholm 2011, pp. 521–522.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 49.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 52.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 123.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2004, pp. 134, 145.

- Poewe & Hexham 2005, p. 195; Schnurbein 2016, pp. 45–46.

- Schnurbein 2016, pp. 46–47.

- Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 177.