Mealworm

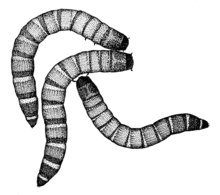

Mealworms are the larval form of the mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor, a species of darkling beetle. Like all holometabolic insects, they go through four life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Larvae typically measure about 2.5 cm or more, whereas adults are generally between 1.25 and 1.8 cm in length.

| Mealworm beetle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Family: | Tenebrionidae |

| Genus: | Tenebrio |

| Species: | T. molitor |

| Binomial name | |

| Tenebrio molitor | |

Reproduction

The mealworm beetle breeds prolifically. Mating is a three-step process: the male chasing the female, mounting her and inserting his aedeagus, and injecting a sperm packet. Within a few days the female burrows into soft ground and lays eggs. Over a lifespan, a female will, on average, lay about 500 eggs.

After four to 19 days the eggs hatch. Many predators target the eggs, including reptiles.

During the larval stage, the mealworm feeds on vegetation and dead insects and molts between each larval stage, or instar (9 to 20 instars). After the final molt it becomes a pupa. The new pupa is whitish, and it turns brown over time. After 3 to 30 days, depending on environmental conditions such as temperature, it emerges as an adult beetle.

Sex pheromones

A sex pheromone released by male mealworms has been identified.[1] Inbreeding reduces the attractiveness of sexual pheromone signaling by male mealworms.[2] Females are more attracted to the odors produced by outbred males than the odors produced by inbred males. The reduction of male signaling capability may be due to increased expression of homozygous deleterious recessive alleles caused by inbreeding.[3]

Relationship with humans

Tenebrio molitor is often used for biological research. Its relatively large size, ease of rearing and handling, and status as a non-model organism make it useful in proof of concept studies in the fields of basic biology, biochemistry, evolution, immunology and physiology.

As pests

Mealworms have generally been considered pests, because their larvae feed on stored grains. Mealworms probably originated in the Mediterranean region, but are now present in many areas of the world as a result of human trade and colonization. The oldest archaeological records of mealworms can be traced to Bronze Age Turkey. Records from the British Isles and northern Europe are from a later date, and mealworms are conspicuously absent from archaeological finds from ancient Egypt.[4]

As feed and pet food

Mealworms are typically used as a pet food for captive reptiles, fish, and birds. They are also provided to wild birds in bird feeders, particularly during the nesting season. Mealworms are useful for their high protein content. They are also used as fishing bait.

They are commercially available in bulk and are typically available in containers with bran or oatmeal for food. Commercial growers incorporate a juvenile hormone into the feeding process to keep the mealworm in the larval stage and achieve an abnormal length of 2 cm or greater.[5]

As food

Mealworms are edible for humans, and processed into several insect food items available in food retail such as insect burgers.

Mealworms have historically been consumed in many Asian countries, particularly in Southeast Asia. They are commonly found in food markets and sold as street food alongside other edible insects. Baked or fried mealworms have been marketed as a healthy snack food in recent history, though the consumption of mealworms goes back centuries. They may be easily reared on fresh oats, wheat bran or grain, with sliced potato, carrots, or apple as a moisture source. The small amount of space required to raise mealworms has made them popular in many parts of Southeast Asia.

Mealworms have been incorporated into tequila-flavored novelty candies. Mealworms are not traditionally served in tequila, and the "tequila worm" in certain mezcals is usually the larva of the moth Hypopta agavis.

Mealworm larvae contain significant nutrient content. For every 100 grams of raw mealworm larvae, 206 calories and anywhere from 14 to 25 grams of protein are contained.[6] Mealworm larvae contain levels of potassium, copper, sodium, selenium, iron and zinc that rival that of beef. Mealworms contain essential linoleic acids as well. They also have greater vitamin content by weight compared to beef, B12 not included.[6][7]

In waste disposal

In 2015, it was discovered that mealworms can degrade polystyrene into usable organic matter at a rate of about 34-39 milligrams per day. Additionally, no difference was found between mealworms fed only styrofoam and mealworms fed conventional foods, during the one-month duration of the experiment.[8] Microorganisms inside the mealworm's gut are responsible for degrading the polystyrene, with mealworms given the antibiotic gentamicin showing no signs of degradation.[9] Isolated colonies of the mealworm's gut microbes, however, have proven less efficient at degradation than the bacteria within the gut.[9] No attempts to commercialize this discovery have been made.[citation needed]

See also

- Zond 5, a 1968 space mission on which mealworms were among the first earthlings to fly to the Moon

- Organisms breaking down plastic

Gallery

In a bedding of bran

In a bedding of bran Mealworm detail

Mealworm detail A mealworm pupa with molted larval skin

A mealworm pupa with molted larval skin New adult

New adult- Mature adult

References

- Bryning GP, Chambers J, Wakefield ME (2005). "Identification of a sex pheromone from male yellow mealworm beetles, Tenebrio molitor". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 31 (11): 2721–30. doi:10.1007/s10886-005-7622-x. PMID 16273437.

- Pölkki M, Krams I, Kangassalo K, Rantala MJ (2012). "Inbreeding affects sexual signalling in males but not females of Tenebrio molitor". Biology Letters. 8 (3): 423–5. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.1135. PMC 3367757. PMID 22237501.

- Bernstein H, Hopf FA, Michod RE (1987). The molecular basis of the evolution of sex. Advances in Genetics. 24. pp. 323–70. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60012-7. ISBN 9780120176243. PMID 3324702.

- Panagiotakopulu E (2001). "New records for ancient pests: archaeoentomology in Egypt". Journal of Archaeological Science. 28 (11): 1235–1246. doi:10.1006/jasc.2001.0697.

- Finke, M.; D. Winn (2004). "Insects and related arthropods: A nutritional primer for rehabilitators". Journal of Wildlife Rehabilitation. 27: 14–17.

- "FAO Nutritional information" (PDF). Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- Schmidt, Anatol; Call, Lisa; Macheiner, Lukas; Mayer, Helmut K. (2018). "Determination of vitamin B12 in four edible insect species by immunoaffinity and ultra-high performance liquid chromatography". Food Chemistry. 281: 124–129. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.039. PMID 30658738.

- Jordan, Rob. "Plastic-eating worms may offer solution to mounting waste, Stanford researchers discover". Stanford News Service. Stanford News Service. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Lockwood, Deirdre (September 30, 2015). "Mealworms Munch Polystyrene Foam". Chemical and Engineering News. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Mealworm beetle |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mealworm beetle. |

- Darkling Beetle/Mealworm Information. Center for Insect Science Education Outreach. University of Arizona.

- Mealworms and Darkling Beetles (Tenebrio beetle). FOSSweb.

- Mealworms.org

- How to Raise Mealworms

- How to Care for Mealworms